|

Audrey Hepburn |

|

|---|---|

Hepburn in 1956 |

|

| Born |

Audrey Kathleen Ruston 4 May 1929 Ixelles, Brussels, Belgium |

| Died | 20 January 1993 (aged 63)

Tolochenaz, Vaud, Switzerland |

| Resting place | Tolochenaz Cemetery, Tolochenaz |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active |

|

| Notable work | Full list |

| Spouses |

Mel Ferrer (m. 1954; div. 1968) Andrea Dotti (m. 1969; div. 1982) |

| Partner | Robert Wolders (1980–1993; her death) |

| Children | 2, including Sean |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF | |

| In office 1989–1993 |

|

| Signature | |

Audrey Hepburn (born Audrey Kathleen Ruston; 4 May 1929 – 20 January 1993) was a British[a] actress and humanitarian. Recognised as both a film and fashion icon, she was ranked by the American Film Institute as the third-greatest female screen legend from the Classical Hollywood cinema and was inducted into the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame.

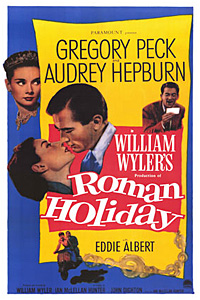

Born in Ixelles, Brussels, to an aristocratic family, Hepburn spent parts of her childhood in Belgium, England, and the Netherlands. She studied ballet with Sonia Gaskell in Amsterdam beginning in 1945, and with Marie Rambert in London from 1948. She began performing as a chorus girl in West End musical theatre productions and then had minor appearances in several films. She rose to stardom in the romantic comedy Roman Holiday (1953) alongside Gregory Peck, for which she was the first actress to win an Oscar, a Golden Globe Award, and a BAFTA Award for a single performance. That year, she also won a Tony Award for Best Lead Actress in a Play for her performance in Ondine.

She went on to star in a number of successful films such as Sabrina (1954), in which Humphrey Bogart and William Holden compete for her affection; Funny Face (1957), a musical where she sang her own parts; the drama The Nun’s Story (1959); the romantic comedy Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961); the thriller-romance Charade (1963), opposite Cary Grant; and the musical My Fair Lady (1964). In 1967 she starred in the thriller Wait Until Dark, receiving Academy Award, Golden Globe, and BAFTA nominations. After that, she only occasionally appeared in films, one being Robin and Marian (1976) with Sean Connery. Her last recorded performances were in the 1990 documentary television series Gardens of the World with Audrey Hepburn for which she won a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Individual Achievement – Informational Programming.

Hepburn won three BAFTA Awards for Best British Actress in a Leading Role. In recognition of her film career, she received BAFTA’s Lifetime Achievement Award, the Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award, the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award, and the Special Tony Award. She remains one of only eighteen people who have won Academy, Emmy, Grammy, and Tony Awards. Later in life, Hepburn devoted much of her time to UNICEF, to which she had contributed since 1954. Between 1988 and 1992, she worked in some of the poorest communities of Africa, South America, and Asia. In December 1992, she received the US Presidential Medal of Freedom in recognition of her work as a UNICEF Goodwill Ambassador. A month later, she died of appendiceal cancer at her home in Tolochenaz, Vaud, Switzerland, at the age of 63.[3]

Early life[edit]

1929–1938: Family and early childhood[edit]

Audrey Kathleen Ruston (later, Hepburn-Ruston[4]) was born on 4 May 1929 at number 48 Rue Keyenveld in Ixelles, Brussels, Belgium.[5] She was known to her family as Adriaantje.[6]

Hepburn’s mother, Baroness Ella van Heemstra (12 June 1900 – 26 August 1984), was a Dutch noblewoman. Ella was the daughter of Baron Aarnoud van Heemstra, who served as mayor of Arnhem from 1910 to 1920 and as governor of Dutch Suriname from 1921 to 1928, and Baroness Elbrig Willemine Henriette van Asbeck (1873–1939), a granddaughter of Count Dirk van Hogendorp.[7] At age 19, she married Jonkheer Hendrik Gustaaf Adolf Quarles van Ufford, an oil executive based in Batavia, Dutch East Indies, where they subsequently lived.[8] They had two sons, Jonkheer Arnoud Robert Alexander Quarles van Ufford (1920–1979) and Jonkheer Ian Edgar Bruce Quarles van Ufford (1924–2010), before divorcing in 1925,[9][10] four years before Hepburn’s birth.[5]

Hepburn’s father, Joseph Victor Anthony Ruston (21 November 1889 – 16 October 1980), was a British subject born in Auschitz, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary.[11] He was the son of Victor John George Ruston, of British and Austrian background[12] and Anna Juliana Franziska Karolina Wels, who was of Czech-Jewish[13] and Austrian origin and born in Kovarce.[14] In 1923–1924, Joseph was an Honorary British Consul in Semarang in the Dutch East Indies,[15] and prior to his marriage to Hepburn’s mother, was married to Cornelia Bisschop, a Dutch heiress.[11][9] Although born with the surname Ruston, he later double-barrelled his name to the more «aristocratic» Hepburn-Ruston, perhaps at Ella’s insistence,[16] as he mistakenly believed himself descended from James Hepburn, third husband of Mary, Queen of Scots.[12][9]

Hepburn’s parents were married in Batavia, Dutch East Indies, in September 1926.[8] At the time, Ruston worked for a trading company, but soon after the marriage, the couple moved to Europe, where he began working for a loan company; reportedly tin merchants MacLaine, Watson and Company in London.[6] After a year in London, they moved to Brussels, where he had been assigned to open a branch office.[8][17] After three years of spending time travelling between Brussels, Arnhem, The Hague and London, the family settled in the suburban Brussels municipality of Linkebeek in 1932.[8][18] Hepburn’s early childhood was sheltered and privileged.[8] Her multinational background was enhanced through her travelling between three countries with her family due to her father’s job.[19][b]

In the mid-1930s, Hepburn’s parents recruited and collected donations for the British Union of Fascists (B.U.F).[20] Her mother met Adolf Hitler and wrote favourable articles about him for the B.U.F.[21] Joseph left the family abruptly in 1935 after a «scene» in Brussels when Adriaantje (as she was known in the family) was six; later she often spoke of the effect on a child of being «dumped» as «children need two parents».[22] Joseph left the family and moved to London, where he became more deeply involved in Fascist activity and never visited his daughter abroad.[23] Hepburn later professed that her father’s departure was «the most traumatic event of my life».[8][24] That same year, her mother moved with Hepburn to her family’s estate in Arnhem; her half-brothers Alex and Ian (then 15 and 11) were sent to The Hague to live with relatives. Joseph wanted her to be educated in England,[25] so in 1937, Hepburn was sent to live in Kent, England, where she, known as Audrey Ruston or «Little Audrey», was educated at a small private school in Elham.[26][27] Hepburn’s parents officially divorced in 1938.[28] In the 1960s, Hepburn renewed contact with her father after locating him in Dublin through the Red Cross; although he remained emotionally detached, Hepburn supported him financially until his death.[29]

1939–1945: Experiences during World War II[edit]

After Britain declared war on Germany in September 1939, Hepburn’s mother moved her daughter back to Arnhem in the hope that, as during the First World War, the Netherlands would remain neutral and be spared a German attack. While there, Hepburn attended the Arnhem Conservatory from 1939 to 1945. She had begun taking ballet lessons during her last years at boarding school, and continued training in Arnhem under the tutelage of Winja Marova, becoming her «star pupil».[8] After the Germans invaded the Netherlands in 1940, Hepburn used the name Edda van Heemstra, because an «English-sounding» name was considered dangerous during the German occupation. Her family was profoundly affected by the occupation, with Hepburn later stating that «had we known that we were going to be occupied for five years, we might have all shot ourselves. We thought it might be over next week… six months… next year… that’s how we got through».[8]

In 1942, her uncle, Otto van Limburg Stirum (husband of her mother’s older sister, Miesje), was executed in retaliation for an act of sabotage by the resistance movement; while he had not been involved in the act, he was targeted due to his family’s prominence in Dutch society.[8] These family events were the turning point in the attitude of Hepburn’s mother, who had flirted with Nazism up to this point. Hepburn’s half-brother Ian was deported to Berlin to work in a German labour camp, and her other half-brother Alex went into hiding to avoid the same fate.[8]

«We saw young men put against the wall and shot, and they’d close the street and then open it, and you could pass by again… Don’t discount anything awful you hear or read about the Nazis. It’s worse than you could ever imagine.»[8]

—Hepburn on the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands

After her uncle’s death, Hepburn, Ella, and Miesje left Arnhem to live with her grandfather, Baron Aarnoud van Heemstra, in nearby Velp.[8] Around that time Hepburn performed silent dance performances which reportedly raised money for the Dutch resistance effort.[30] It was long believed that she participated in the Dutch resistance itself,[8] but in 2016 the Airborne Museum ‘Hartenstein’ reported that after extensive research it had not found any evidence of such activities.[31] However, a 2019 book by author Robert Matzen provided evidence that she had supported the resistance by giving «underground concerts» to raise money, delivering the underground newspaper, and taking messages and food to downed Allied flyers hiding in the woodlands north of Velp.[32] She also volunteered at a hospital that was the center of resistance activities in Velp,[32] and her family temporarily hid a British paratrooper in their home during the Battle of Arnhem.[33][34] In addition to other traumatic events, she witnessed the transportation of Dutch Jews to concentration camps, later stating that «more than once I was at the station seeing trainloads of Jews being transported, seeing all these faces over the top of the wagon. I remember, very sharply, one little boy standing with his parents on the platform, very pale, very blond, wearing a coat that was much too big for him, and he stepped on the train. I was a child observing a child.»[35]

After the Allied landing on D-Day, living conditions grew worse, and Arnhem was subsequently heavily damaged during Operation Market Garden. During the 1944-45 Dutch famine, the Germans hindered or reduced the already limited food and fuel supplies to civilians in retaliation for Dutch railway strikes that were held to hinder the occupation. Like others, Hepburn’s family resorted to making flour out of tulip bulbs to bake cakes and biscuits;[36][37] a source of starchy carbohydrates; Dutch doctors provided recipes for using tulip bulbs throughout the famine.[38] Suffering from the effects of malnutrition, after the war ended Hepburn become gravely ill with jaundice, anaemia, oedema, and a respiratory infection. In October 1945, a letter from Ella asking for help was received by Micky Burn, a former lover and British Army officer with whom she had corresponded whilst he was a prisoner of war in Colditz Castle. He sent back thousands of cigarettes, which she was able to sell on the black market and so buy the Penicillin which saved Hepburn’s life.[39][40][41] However, the financial situation of the Van Heemstra family was changed significantly as a result of the occupation, during which time many of their properties (including their principal estate in Arnhem) were badly damaged or destroyed.[42]

Entertainment career[edit]

1945–1952: Ballet studies and early acting roles[edit]

After the war ended in 1945, Hepburn moved with her mother and siblings to Amsterdam, where she began ballet training under Sonia Gaskell, a leading figure in Dutch ballet, and Russian teacher Olga Tarasova.[43]

Due to the loss of the family fortune, Ella had to support them by working as a cook and housekeeper for a wealthy family.[44] Hepburn made her film debut playing an air stewardess in Dutch in Seven Lessons (1948), an educational travel film made by Charles van der Linden and Henry Josephson.[45] Later that year, Hepburn moved to London after accepting a ballet scholarship with Ballet Rambert, which was then based in Notting Hill.[46][c] She supported herself with part-time work as a model, and dropped «Ruston» from her surname. After she was told by Rambert that despite her talent, her height and weak constitution (the after-effect of wartime malnutrition) would make the status of prima ballerina unattainable, she decided to concentrate on acting.[47][48][49]

While Ella worked in menial jobs to support them, Hepburn appeared as a chorus girl[50] in the West End musical theatre revues High Button Shoes (1948) at the London Hippodrome, and Cecil Landeau’s Sauce Tartare (1949) and Sauce Piquante (1950) at the Cambridge Theatre. Also, in 1950, she worked as a dancer in an exceptionally «ambitious» revue, Summer Nights, at Ciro’s London, a prominent nightclub.[51]

During her theatrical work, she took elocution lessons with actor Felix Aylmer to develop her voice.[52] After being spotted by the Ealing Studios casting director, Margaret Harper-Nelson, while performing in Sauce Piquante, Hepburn was registered as a freelance actress with the Associated British Picture Corporation (ABPC). She appeared in the BBC Television play The Silent Village,[53] and in minor roles in the films One Wild Oat, Laughter in Paradise, Young Wives’ Tale, and The Lavender Hill Mob (all 1951). She was cast in her first major supporting role in Thorold Dickinson’s Secret People (1952), as a prodigious ballerina, performing all of her own dancing sequences.[54]

Hepburn was then offered a small role in a film being shot in both English and French, Monte Carlo Baby (French: Nous Irons à Monte Carlo, 1952), which was filmed in Monte Carlo. Coincidentally, French novelist Colette was at the Hôtel de Paris in Monte Carlo during the filming, and decided to cast Hepburn in the title role in the Broadway play Gigi.[55] Hepburn went into rehearsals having never spoken on stage, and required private coaching.[56] When Gigi opened at the Fulton Theatre on 24 November 1951, she received praise for her performance, despite criticism that the stage version was inferior to the French film adaptation.[57] Life called her a «hit»,[57] while The New York Times stated that «her quality is so winning and so right that she is the success of the evening».[56] Hepburn also received a Theatre World Award for the role.[58] The play ran for 219 performances, closing on 31 May 1952,[58] before going on tour, which began 13 October 1952 in Pittsburgh and visited Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Washington, D. C., and Los Angeles, before closing on 16 May 1953 in San Francisco.[8]

1953–1960: Roman Holiday and stardom[edit]

Hepburn had her first starring role in Roman Holiday (1953), playing Princess Ann, a European princess who escapes the reins of royalty and has a wild night out with an American newsman (Gregory Peck). On 18 September 1951, shortly after Secret People was finished but before its premiere, Thorold Dickinson made a screen test with the young starlet and sent it to director William Wyler, who was in Rome preparing Roman Holiday. Wyler wrote a glowing note of thanks to Dickinson, saying that «as a result of the test, a number of the producers at Paramount have expressed interest in casting her.»[59] The producers of the movie had initially wanted Elizabeth Taylor for the role, but Wyler was so impressed by Hepburn’s screen test that he cast her instead. Wyler later commented, «She had everything I was looking for: charm, innocence, and talent. She also was very funny. She was absolutely enchanting, and we said, ‘That’s the girl!‘«[60] Originally, the film was to have had only Gregory Peck’s name above its title, with «Introducing Audrey Hepburn» beneath in smaller font. However, Peck suggested to Wyler that he elevate her to equal billing so that her name appeared before the title, and in type as large as his: «You’ve got to change that because she’ll be a big star, and I’ll look like a big jerk.»[61]

The film was a box-office success, and Hepburn gained critical acclaim for her portrayal, unexpectedly winning an Academy Award for Best Actress, a BAFTA Award for Best British Actress in a Leading Role, and a Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Motion Picture Drama in 1953. In his review in The New York Times, A. H. Weiler wrote: «Although she is not precisely a newcomer to films, Audrey Hepburn, the British actress who is being starred for the first time as Princess Anne, is a slender, elfin, and wistful beauty, alternately regal and childlike in her profound appreciation of newly-found, simple pleasures and love. Although she bravely smiles her acknowledgement of the end of that affair, she remains a pitifully lonely figure facing a stuffy future.»[62]

Hepburn was signed to a seven-picture contract with Paramount, with 12 months in between films to allow her time for stage work.[63] She was featured on 7 September 1953 cover of Time magazine, and also became known for her personal style.[64] Following her success in Roman Holiday, Hepburn starred in Billy Wilder’s romantic Cinderella-story comedy Sabrina (1954), in which wealthy brothers (Humphrey Bogart and William Holden) compete for the affections of their chauffeur’s innocent daughter (Hepburn). For her performance, she was nominated for the 1954 Academy Award for Best Actress, while winning the BAFTA Award for Best Actress in a Leading Role the same year.[65] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times stated that she was «a young lady of extraordinary range of sensitive and moving expressions within such a frail and slender frame. She is even more luminous as the daughter and pet of the servants’ hall than she was as a princess last year, and no more than that can be said.»[66]

Hepburn also returned to the stage in 1954, playing a water nymph who falls in love with a human in the fantasy play Ondine on Broadway. A critic for The New York Times commented that «somehow, Miss Hepburn is able to translate [its intangibles] into the language of the theatre without artfulness or precociousness. She gives a pulsing performance that is all grace and enchantment, disciplined by an instinct for the realities of the stage». Her performance won her the 1954 Tony Award for Best Performance by a Leading Actress in a Play three days after she won the Academy Award for Roman Holiday, making her one of three actresses to receive the Academy and Tony Awards for Best Actress in the same year (the other two are Shirley Booth and Ellen Burstyn).[67] During the production, Hepburn and her co-star Mel Ferrer began a relationship, and were married on 25 September 1954 in Switzerland.[68]

Although she appeared in no new film releases in 1955, Hepburn received the Golden Globe for World Film Favorite that year.[69] Having become one of Hollywood’s most popular box-office attractions, she starred in a series of successful films during the remainder of the decade, including her BAFTA- and Golden Globe-nominated role as Natasha Rostova in War and Peace (1956), an adaptation of the Tolstoy novel set during the Napoleonic wars, starring Henry Fonda and her husband Mel Ferrer. She exhibited her dancing abilities in her debut musical film, Funny Face (1957), wherein Fred Astaire, a fashion photographer, discovers a beatnik bookstore clerk (Hepburn) who, lured by a free trip to Paris, becomes a beautiful model. Hepburn starred in another romantic comedy, Love in the Afternoon (also 1957), alongside Gary Cooper and Maurice Chevalier.

Hepburn played Sister Luke in The Nun’s Story (1959), which focuses on the character’s struggle to succeed as a nun, alongside co-star Peter Finch. The role produced a third Academy Award nomination for Hepburn, and earned her a second BAFTA Award. A review in Variety reads: «Hepburn has her most demanding film role, and she gives her finest performance»,[70] while Henry Hart in Films in Review stated that her performance «will forever silence those who have thought her less an actress than a symbol of the sophisticated child/woman. Her portrayal of Sister Luke is one of the great performances of the screen.»[71] Hepburn spent a year researching and working on the role, saying, «I

gave more time, energy, and thought to this role than to any of my previous screen performances».[72]

Following The Nun’s Story, Hepburn received a lukewarm reception for starring with Anthony Perkins in the romantic adventure Green Mansions (1959), in which she played Rima, a jungle girl who falls in love with a Venezuelan traveller,[73] and The Unforgiven (1960), her only western film, in which she appeared opposite Burt Lancaster and Lillian Gish in a story of racism against a group of Native Americans.[74]

1961–1967: Breakfast at Tiffany’s and continued success[edit]

Hepburn next starred as New Yorker Holly Golightly in Blake Edwards’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), a film loosely based on the Truman Capote novella of the same name. Capote disapproved of many changes that were made to sanitise the story for the film adaptation, and would have preferred Marilyn Monroe to have been cast in the role, although he also stated that Hepburn «did a terrific job».[75] The character is considered one of the best-known in American cinema, and a defining role for Hepburn.[76] The dress she wears during the opening credits has been considered an icon of the twentieth century, and perhaps the most famous «little black dress» of all time.[77][78][79][80] Hepburn stated that the role was «the jazziest of my career»[81] yet admitted: «I’m an introvert. Playing the extroverted girl was the hardest thing I ever did.»[82] She was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance.

The same year, Hepburn also starred in William Wyler’s drama The Children’s Hour (1961), in which she and Shirley MacLaine played teachers whose lives become troubled after two pupils accuse them of being lesbians.[83][84] Bosley Crowther of The New York Times was of the opinion that the film «is not too well acted», with the exception of Hepburn, who «gives the impression of being sensitive and pure» of its «muted theme».[83] Variety magazine also complimented Hepburn’s «soft sensitivity, marvelous projection and emotional understatement», adding that Hepburn and MacLaine «beautifully complement each other».[84]

Hepburn next appeared opposite Cary Grant in the comic thriller Charade (1963), playing a young widow pursued by several men who chase after the fortune stolen by her murdered husband. The 59-year-old Grant, who had previously withdrawn from the starring male lead roles in Roman Holiday and Sabrina, was sensitive about his age difference with 34-year-old Hepburn, and was uncomfortable about the romantic interplay. To satisfy his concerns, the filmmakers agreed to alter the screenplay so that Hepburn’s character was pursuing him.[85] The film turned out to be a positive experience for him; he said, «All I want for Christmas is another picture with Audrey Hepburn.»[86] The role earned Hepburn her third, and final, competitive BAFTA Award, and another Golden Globe nomination. Critic Bosley Crowther was less kind to her performance, stating that, «Hepburn is cheerfully committed to a mood of how-nuts-can-you-be in an obviously comforting assortment of expensive Givenchy costumes.»[87]

Hepburn reunited with her Sabrina co-star William Holden in Paris When It Sizzles (1964), a screwball comedy in which she played the young assistant of a Hollywood screenwriter, who aids his writer’s block by acting out his fantasies of possible plots. Its production was troubled by several problems. Holden unsuccessfully tried to rekindle a romance with the now-married Hepburn, and his alcoholism was beginning to affect his work. After principal photography began, she demanded the dismissal of cinematographer Claude Renoir after seeing what she felt were unflattering dailies.[88] Superstitious, she also insisted on dressing room 55 because that was her lucky number and required that Hubert de Givenchy, her long-time designer, be given a credit in the film for her perfume.[88] Dubbed «marshmallow-weight hokum» by Variety upon its release in April,[89] the film was «uniformly panned»[88] but critics were kinder to Hepburn’s performance, describing her as «a refreshingly individual creature in an era of the exaggerated curve».[89]

Hepburn’s second film released in 1964 was George Cukor’s film adaptation of the stage musical My Fair Lady, which premiered in October.[90] Soundstage wrote that «not since Gone with the Wind has a motion picture created such universal excitement as My Fair Lady«,[67] although Hepburn’s casting in the role of Cockney flower girl Eliza Doolittle was a source of dispute. Julie Andrews, who had originated the role on stage, was not offered the part because producer Jack L. Warner thought Hepburn was a more «bankable» proposition. Hepburn initially asked Warner to give the role to Andrews but was eventually cast. Further friction was created when, although non-singer Hepburn had sung in Funny Face and had lengthy vocal preparation for the role in My Fair Lady, her vocals were dubbed by Marni Nixon, whose voice was considered more suitable to the role.[91][92] Hepburn was initially upset and walked off the set when informed.[d]

Critics applauded Hepburn’s performance. Crowther wrote that, «The happiest thing about [My Fair Lady] is that Audrey Hepburn superbly justifies the decision of Jack Warner to get her to play the title role.»[91] Gene Ringgold of Soundstage also commented that, «Audrey Hepburn is magnificent. She is Eliza for the ages»,[67] while adding, «Everyone agreed that if Julie Andrews was not to be in the film, Audrey Hepburn was the perfect choice.»[67] The reviewer in Time magazine said her «graceful, glamorous performance» was «the best of her career».[93] Andrews won an Academy Award for Mary Poppins at the 1964 37th Academy Awards, but Hepburn was not even nominated. On the other hand, Hepburn did receive Best Actress nominations for both Golden Globe and New York Film Critics Circle awards.[94]

As the decade carried on, Hepburn appeared in an assortment of genres including the heist comedy How to Steal a Million (1966). Hepburn played the daughter of a famous art collector, whose collection consists entirely of forgeries which are about to be exposed as fakes. Her character plays the part of a dutiful daughter trying to help her father with the help of a man played by Peter O’Toole. The film was followed by two films in 1967. The first was Two for the Road, a non-linear and innovative British dramedy that traces the course of a couple’s troubled marriage. Director Stanley Donen said that Hepburn was freer and happier than he had ever seen her, and he credited that to co-star Albert Finney.[95] The second, Wait Until Dark, is a suspense thriller in which Hepburn demonstrated her acting range by playing the part of a terrorised blind woman. Filmed on the brink of her divorce, it was a difficult film for her, as husband Mel Ferrer was its producer. She lost fifteen pounds under the stress, but she found solace in co-star Richard Crenna and director Terence Young. Hepburn earned her fifth and final competitive Academy Award nomination for Best Actress; Bosley Crowther affirmed, «Hepburn plays the poignant role, the quickness with which she changes and the skill with which she manifests terror attract sympathy and anxiety to her and give her genuine solidity in the final scenes.»[96]

1968–1993: Semi-retirement and final projects[edit]

After 1967, Hepburn chose to devote more time to her family and acted only occasionally in the following decades. She attempted a comeback playing Maid Marian in the period piece Robin and Marian (1976) with Sean Connery co-starring as Robin Hood, which was moderately successful. Roger Ebert praised Hepburn’s chemistry with Connery, writing, «Connery and Hepburn seem to have arrived at a tacit understanding between themselves about their characters. They glow. They really do seem in love. And they project as marvelously complex, fond, tender people; the passage of 20 years has given them grace and wisdom.»[97] Hepburn reunited with director Terence Young in the production of Bloodline (1979), sharing top-billing with Ben Gazzara, James Mason, and Romy Schneider.[98] The film, an international intrigue amid the jet-set, was a critical and box-office failure. Hepburn’s last starring role in a feature film was opposite Gazzara in the comedy They All Laughed (1981), directed by Peter Bogdanovich.[99] The film was overshadowed by the murder of one of its stars, Dorothy Stratten, and received only a limited release. Six years later, Hepburn co-starred with Robert Wagner in a made-for-television caper film, Love Among Thieves (1987).[100]

After finishing her last motion picture role—a cameo appearance as an angel in Steven Spielberg’s Always (1989)—Hepburn completed only two more entertainment-related projects, both critically acclaimed. Gardens of the World with Audrey Hepburn was a PBS documentary series, which was filmed on location in seven countries in the spring and summer of 1990. A one-hour special preceded it in March 1991, and the series itself began its national PBS premiere on 24 January 1993, the day of her funeral services in Tolochenaz. For the «Flower Gardens» episode, Hepburn was posthumously awarded the 1993 Emmy Award for Outstanding Individual Achievement – Informational Programming. The other project was a spoken word album, Audrey Hepburn’s Enchanted Tales, which features readings of classic children’s stories and was recorded in 1992. It earned her a posthumous Grammy Award for Best Spoken Word Album for Children.[101]

Humanitarian career[edit]

In the 1950s, Hepburn narrated two radio programmes for UNICEF, re-telling children’s stories of war.[102] In 1989, Hepburn was appointed a Goodwill Ambassador of UNICEF. On her appointment, she stated that she was grateful for receiving international aid after enduring the German occupation as a child, and wanted to show her gratitude to the organisation.[103]

1988–1989[edit]

Hepburn’s first field mission for UNICEF was to Ethiopia in 1988. She visited an orphanage in Mek’ele that housed 500 starving children and had UNICEF send food.[104] Of the trip, she said,

I have a broken heart. I feel desperate. I can’t stand the idea that two million people are in imminent danger of starving to death, many of them children, [and] not because there isn’t tons of food sitting in the northern port of Shoa. It can’t be distributed. Last spring, Red Cross and UNICEF workers were ordered out of the northern provinces because of two simultaneous civil wars… I went into rebel country and saw mothers and their children who had walked for ten days, even three weeks, looking for food, settling onto the desert floor into makeshift camps where they may die. Horrible. That image is too much for me. The ‘Third World’ is a term I don’t like very much, because we’re all one world. I want people to know that the largest part of humanity is suffering.[105]

In August 1988, Hepburn went to Turkey on an immunisation campaign. She called Turkey «the loveliest example» of UNICEF’s capabilities. Of the trip, she said, «The army gave us their trucks, the fishmongers gave their wagons for the vaccines, and once the date was set, it took ten days to vaccinate the whole country. Not bad.»[104] In October, Hepburn went to South America. Of her experiences in Venezuela and Ecuador, Hepburn told the United States Congress, «I saw tiny mountain communities, slums, and shantytowns receive water systems for the first time by some miracle – and the miracle is UNICEF. I watched boys build their own schoolhouse with bricks and cement provided by UNICEF.»[106]

Hepburn toured Central America in February 1989, and met with leaders in Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala. In April, she visited Sudan with Wolders as part of a mission called «Operation Lifeline». Because of civil war, food from aid agencies had been cut off. The mission was to ferry food to southern Sudan. Hepburn said, «I saw but one glaring truth: These are not natural disasters but man-made tragedies for which there is only one man-made solution – peace.»[104] In October 1989, Hepburn and Wolders went to Bangladesh. John Isaac, a UN photographer, said, «Often the kids would have flies all over them, but she would just go hug them. I had never seen that. Other people had a certain amount of hesitation, but she would just grab them. Children would just come up to hold her hand, touch her – she was like the Pied Piper.»[8]

1990–1992[edit]

In October 1990, Hepburn went to Vietnam, in an effort to collaborate with the government for national UNICEF-supported immunisation and clean water programmes. In September 1992, four months before she died, Hepburn went to Somalia. Calling it «apocalyptic», she said, «I walked into a nightmare. I have seen famine in Ethiopia and Bangladesh, but I have seen nothing like this – so much worse than I could possibly have imagined. I wasn’t prepared for this.»[104] Though scarred by what she had seen, Hepburn still had hope stating:

As we move into the twenty-first century, there is much to reflect upon. We look around us and see that the promises of yesterday have to come to pass. People still live in abject poverty, people are still hungry, people still struggle to survive. And among these people we see the children, always the children: their enlarged bellies, their sad eyes, their wise faces that show the suffering, all the suffering they have endured in their short years.[107]

Recognition[edit]

United States president George H. W. Bush presented Hepburn with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in recognition of her work with UNICEF, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences posthumously awarded her the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award for her contribution to humanity.[108][109] In 2002, at the United Nations Special Session on Children, UNICEF honoured Hepburn’s legacy of humanitarian work by unveiling a statue, «The Spirit of Audrey», at UNICEF’s New York headquarters. Her service for children is also recognised through the United States Fund for UNICEF’s Audrey Hepburn Society.[110][111]

Personal life[edit]

Marriages, relationships, and children[edit]

In 1952, Hepburn became engaged to industrialist James Hanson,[112] whom she had known since her early days in London. She called it «love at first sight», but after having her wedding dress fitted and the date set, she decided the marriage would not work because the demands of their careers would keep them apart most of the time.[113] She issued a public statement about her decision, saying «When I get married, I want to be really married».[114] In the early 1950s, she also dated future Hair producer Michael Butler.[115]

At a cocktail party hosted by mutual friend Gregory Peck, Hepburn met American actor Mel Ferrer, and suggested that they star together in a play.[67][116] The meeting led them to collaborate in Ondine, during which they began a relationship. Eight months later, on 25 September 1954, they were married in Bürgenstock, Switzerland,[117] while preparing to star together in the film War and Peace (1956). She and Ferrer had a son, Sean Hepburn Ferrer.[118][119]

Despite the insistence from gossip columns that their marriage would not last, Hepburn claimed that she and Ferrer were inseparable and happy together, though she admitted that he had a bad temper. Ferrer was rumoured to be too controlling, and had been referred to by others as being her «Svengali» – an accusation that Hepburn laughed off. William Holden was quoted as saying, «I think Audrey allows Mel to think he influences her.» After a 14-year marriage, the couple divorced in 1968.[120]

Hepburn met her second husband, Italian psychiatrist Andrea Dotti, on a Mediterranean cruise with friends in June 1968. She believed she would have more children and possibly stop working.[121][122] They married on 18 January 1969, and their son Luca Andrea Dotti was born on 8 February 1970.[119] While pregnant with Luca in 1969, Hepburn was more careful, resting for months before delivering the baby via caesarean section. Hepburn suffered a miscarriage in 1974.[119]

Both Dotti and Hepburn were unfaithful, with Dotti having affairs with younger women and Hepburn having a romantic relationship with actor Ben Gazzara during the filming of the movie Bloodline (1979).[123] The Dotti-Hepburn marriage lasted more than twelve years and was dissolved in 1982.[119][124]

From 1980 until her death, Hepburn was in a relationship with Dutch actor Robert Wolders,[37] the widower of actress Merle Oberon. She had met Wolders through a friend during the later years of her second marriage. In 1989, she called the nine years she had spent with him the happiest years of her life, and stated that she considered them married, just not officially.[125]

Illness and death[edit]

Upon returning from Somalia to Switzerland in late September 1992, Hepburn developed abdominal pain. While initial medical tests in Switzerland had inconclusive results, a laparoscopy performed at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles in early November revealed a rare form of abdominal cancer belonging to a group of cancers known as pseudomyxoma peritonei.[126] Having grown slowly over several years, the cancer had metastasised as a thin coating over her small intestine. After surgery, Hepburn began chemotherapy.[127]

Hepburn and her family returned home to Switzerland to celebrate her last Christmas. As she was still recovering from surgery, she was unable to fly on commercial aircraft. Her long-time friend, fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy, arranged for socialite Rachel Lambert «Bunny» Mellon to send her private Gulfstream jet, filled with flowers, to take Hepburn from Los Angeles to Geneva. She spent her last days in hospice care at her home in Tolochenaz, Vaud, and was occasionally well enough to take walks in her garden, but gradually became more confined to bedrest.[128]

On the evening of 20 January 1993, Hepburn died in her sleep at home. After her death, Gregory Peck recorded a tribute to Hepburn in which he recited the poem «Unending Love» by Rabindranath Tagore.[129] Funeral services were held at the village church of Tolochenaz on 24 January 1993. Maurice Eindiguer, the same pastor who wed Hepburn and Mel Ferrer and baptised her son Sean in 1960, presided over her funeral, while Prince Sadruddin Aga Khan of UNICEF delivered a eulogy. Many family members and friends attended the funeral, including her sons, partner Robert Wolders, half-brother Ian Quarles van Ufford, ex-husbands Andrea Dotti and Mel Ferrer, Hubert de Givenchy, executives of UNICEF, and fellow actors Alain Delon and Roger Moore.[130] Flower arrangements were sent to the funeral by Gregory Peck, Elizabeth Taylor, and the Dutch royal family.[131]

Later on the same day, Hepburn was interred at the Tolochenaz Cemetery.[132]

Legacy[edit]

Hepburn’s legacy has endured long after her death. The American Film Institute named Hepburn third among the Greatest Female Stars of All Time. She is one of few entertainers who have won Academy, Emmy, Grammy and Tony Awards. She won a record three BAFTA Awards for Best British Actress in a Leading Role. In her last years, she remained a visible presence in the film world. She received a tribute from the Film Society of Lincoln Center in 1991 and was a frequent presenter at the Academy Awards. She received the BAFTA Lifetime Achievement Award in 1992.[133] She was the recipient of numerous posthumous awards including the 1993 Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award and competitive Grammy and Emmy Awards. In January 2009, Hepburn was named on The Times‘ list of the top 10 British actresses of all time.[133] However, in 2010 Emma Thompson commented that Hepburn «can’t sing and she can’t really act»; some people agreed, others did not.[134] Hepburn’s son Sean later said «My mother would be the first person to say that she wasn’t the best actress in the world. But she was a movie star.»[135]

She has been the subject of many biographies since her death including the 2000 dramatisation of her life titled The Audrey Hepburn Story which starred Jennifer Love Hewitt and Emmy Rossum as the older and younger Hepburn respectively.[136] Her son and granddaughter, Sean and Emma Ferrer, helped produce a biographical documentary directed by Helena Coan, entitled Audrey (2020). The film was released to positive reception.[137][138] Hepburn’s image is widely used in advertising campaigns across the world. In Japan, a series of commercials used colourised and digitally enhanced clips of Hepburn in Roman Holiday to advertise Kirin black tea. In the United States, Hepburn was featured in a 2006 Gap commercial which used clips of her dancing from Funny Face, set to AC/DC’s «Back in Black», with the tagline «It’s Back – The Skinny Black Pant». To celebrate its «Keep it Simple» campaign, the Gap made a sizeable donation to the Audrey Hepburn Children’s Fund.[139] In 2012, Hepburn was among the British cultural icons selected by artist Sir Peter Blake to appear in a new version of his best known artwork – the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover – to celebrate the British cultural figures of his life that he most admires.[140] In 2013, a computer-manipulated representation of Hepburn was used in a television advert for the British chocolate bar Galaxy.[141][142] On 4 May 2014, Google featured a doodle on its homepage on what would have been Hepburn’s 85th birthday.[143]

Sean Ferrer founded the Audrey Hepburn Children’s Fund[144] in memory of his mother shortly after her death. The US Fund for UNICEF also founded the Audrey Hepburn Society: the Society hosted annual charity balls for fund raising until Ferrer became involved in lawsuits in the late 2010s on behalf of his mother’s estate.[145][146] Dotti also became patron of the Pseudomyxoma Survivor charity, dedicated to providing support to patients of the rare cancer which was fatal to Hepburn, pseudomyxoma peritonei,[147] and Sean Ferrer became the rare disease ambassador since 2014 and for 2015 on behalf of European Organisation for Rare Diseases.[148] A year after his mother’s death in 1993, Ferrer founded the Audrey Hepburn Children’s Fund (originally named Hollywood for Children Inc.),[149] a charity funded by exhibitions of Audrey Hepburn memorabilia. He directed the charity in cooperation with his half-brother Luca Dotti, and Robert Wolders, his mother’s partner, which aimed to continue the humanitarian work of Audrey Hepburn.[150] Ferrer brought the exhibition «Timeless Audrey» on a world tour to raise money for the foundation.[151] He served as Chairman of the Fund before resigning in 2012, turning over the position to Dotti.[152] In 2017, Ferrer was sued by the Fund for alleged self-serving conduct.[152] In October 2017, Ferrer responded by suing the Fund for trademark infringement, claiming that the Fund no longer had the right to use Hepburn’s name or likeness.[149] Ferrer’s suit against the Fund was dismissed in March 2018 due to the complaint’s failure to include Dotti as a defendant.[153] In 2019, the court sided with Ferrer, with the judge ruling there was no merit to the charity’s claims it had the independent right to use Audrey Hepburn’s name and likeness, or to enter into contracts with third parties without Ferrer’s consent.[145][146]

Hepburn’s son Sean said that he was brought up in the countryside as a normal child, not in Hollywood and without a Hollywood state of mind that makes movie stars and their families lose touch with reality. There was no screening room in the house. He said that his mother didn’t take herself seriously, and used to say, «I take what I do seriously, but I don’t take myself seriously».[135]

Public image and style icon[edit]

Hepburn with a short hairstyle and wearing one of her signature looks: black turtleneck, slim black trousers, and ballet flats

Hepburn was known for her fashion choices and distinctive look, to the extent that journalist Mark Tungate has described her as a recognisable brand.[154] When she first rose to stardom in Roman Holiday (1953), she was seen as an alternative feminine ideal that appealed more to women than men, in comparison to the curvy and more sexual Grace Kelly and Elizabeth Taylor.[155][156] With her short hairstyle, thick eyebrows, slim body, and «gamine» looks, she presented a look which young women found easier to emulate than those of more sexual film stars.[157] In 1954, fashion photographer Cecil Beaton declared Hepburn the «public embodiment of our new feminine ideal» in Vogue, and wrote that «Nobody ever looked like her before World War II … Yet we recognise the rightness of this appearance in relation to our historical needs. The proof is that thousands of imitations have appeared.»[156] The magazine and its British version frequently reported on her style throughout the following decade.[158] Alongside model Twiggy, Hepburn has been cited as one of the key public figures who made being very slim fashionable.[157] Vogue has referred to her as «the acme of classic beauty».[159]

Added to the International Best Dressed List in 1961, Hepburn was associated with a minimalistic style, usually wearing clothes with simple silhouettes which emphasised her slim body, monochromatic colours, and occasional statement accessories.[160] In the late 1950s, Audrey Hepburn popularised plain black leggings.[161] Hepburn was in particular associated with French fashion designer Hubert de Givenchy, who was first hired to design her on-screen wardrobe for her second Hollywood film, Sabrina (1954), when she was still unknown as a film actor and he a young couturier just starting his fashion house.[162] Although initially disappointed that «Miss Hepburn» was not Katharine Hepburn as he had mistakenly thought, Givenchy and Hepburn formed a life-long friendship.[162][163]

In addition to Sabrina, Givenchy designed her costumes for Love in the Afternoon (1957), Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), Funny Face (1957), Charade (1963), Paris When It Sizzles (1964), and How to Steal a Million (1966), as well as clothed her off screen.[162] According to Moseley, fashion plays an unusually central role in many of Hepburn’s films, stating that «the costume is not tied to the character, functioning ‘silently’ in the mise-en-scène, but as ‘fashion’ becomes an attraction in the aesthetic in its own right».[164] She also became the face of Givenchy’s first perfume, L’Interdit, in 1957.[165] In addition to her partnership with Givenchy, Hepburn was credited with boosting the sales of Burberry trench coats when she wore one in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and was associated with Italian footwear brand Tod’s.[166]

In her private life, Hepburn preferred to wear casual and comfortable clothes, contrary to the haute couture she wore on screen and at public events.[167] Despite being admired for her beauty, she never considered herself attractive, stating in a 1959 interview that «you can even say that I hated myself at certain periods. I was too fat, or maybe too tall, or maybe just plain too ugly… you can say my definiteness stems from underlying feelings of insecurity and inferiority. I couldn’t conquer these feelings by acting indecisive. I found the only way to get the better of them was by adopting a forceful, concentrated drive.»[168] In 1989, she stated that «my look is attainable … Women can look like Audrey Hepburn by flipping out their hair, buying the large glasses and the little sleeveless dresses.»[160]

Hepburn’s influence as a style icon continues several decades after the height of her acting career in the 1950s and 1960s. Moseley notes that especially after her death in 1993, she became increasingly admired, with magazines frequently advising readers on how to get her look and fashion designers using her as inspiration.[169][157] Throughout her career and after her death, Hepburn received numerous accolades for her stylish appearance and attractiveness. For example, she was named the «most beautiful woman of all time»[170] and «most beautiful woman of the 20th century»[171] in polls by Evian and QVC respectively, and in 2015, was voted «the most stylish Brit of all time» in a poll commissioned by Samsung.[172] Her film costumes fetch large sums of money in auctions: one of the «little black dresses» designed by Givenchy for Breakfast at Tiffany’s was sold by Christie’s for a record sum of £467,200 in 2006.[173][e]

Filmography and stage roles[edit]

Hepburn was considered by some to be one of the most beautiful women of all time,[178][179] she was ranked as the third greatest screen legend in American cinema by the American Film Institute.[180] Hepburn is also remembered as both a film and style icon.[181][182][183] Her debut was as a flight stewardess in the 1948 Dutch film Dutch in Seven Lessons.[46] Hepburn then performed on the British stage as a chorus girl in the musicals High Button Shoes (1948), and Sauce Tartare (1949). Two years later she made her Broadway debut as the title character in the play Gigi. Hepburn’s Hollywood debut as a runaway princess in William Wyler’s Roman Holiday (1953) opposite Gregory Peck made her a star.[181][184][185] For her performance she received the Academy Award for Best Actress, the BAFTA Award for Best British Actress, and the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama.[186][187][188] In 1954 she played a chauffeur’s daughter caught in a love triangle in Billy Wilder’s romantic comedy Sabrina opposite Humphrey Bogart and William Holden.[189][190] In the same year Hepburn garnered the Tony Award for Best Actress in a Play for portraying the titular water nymph in the play Ondine.[191][192]

Awards and honours[edit]

Hepburn received numerous awards and honours during her career. Hepburn won, or was nominated for, awards for her work in motion pictures, television, spoken-word recording, on stage, and humanitarian work. She was five-times nominated for an Academy Award, and she was awarded the 1953 Academy Award for Best Actress for her performance in Roman Holiday and the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award in 1993, posthumously, for her humanitarian work. From 5 nominations, she won a record three BAFTA Awards for Best British Actress in a Leading Role, and received a BAFTA Special Award in 1992.[193][194][195]

See also[edit]

- L’Interdit

- List of EGOT winners

- Sophia (robot) – A humanoid robot modelled after Audrey Hepburn

- White floral Givenchy dress of Audrey Hepburn (Academy Awards, 1954)

Notes[edit]

- ^ She solely held British nationality, since at the time of her birth Dutch women were not permitted to pass on their nationality to their children; the Dutch law did not change in this regard until 1985.[1] A further reference is her birth certificate which clearly states British nationality. When asked about her background, Hepburn identified as half-Dutch,[2] as her mother was a Dutch noblewoman. Furthermore, she spent a significant number of her formative years in the Netherlands and was able to speak Dutch fluently. Her ancestry is covered in the «Early life» section.

- ^ Walker writes that it is unclear for what kind of company he worked; he was listed as a «financial adviser» in a Dutch business directory, and the family often travelled among the three countries.[19]

- ^ She had been offered the scholarship already in 1945, but had had to decline it due to «some uncertainty regarding her national status».[42]

- ^ Overall, about 90% of her singing was dubbed, despite being promised that most of her vocals would be used. Hepburn’s voice remains in one line in «I Could Have Danced All Night», in the first verse of «Just You Wait», and in the entirety of its reprise in addition to sing-talking in parts of «The Rain in Spain» in the finished film. When asked about the dubbing of an actress with such distinctive vocal tones, Hepburn frowned and said, «You could tell, couldn’t you? And there was Rex, recording all his songs as he acted … next time —» She bit her lip to prevent her saying more.[82] She later admitted that she would have never accepted the role knowing that Warner intended to have nearly all of her singing dubbed.

- ^ This was the highest price paid for a dress from a film,[174] until it was surpassed by the $4.6 million paid in June 2011 for Marilyn Monroe’s «subway dress» from The Seven Year Itch.[175] Of the two dresses that Hepburn wore on screen, one is held in the Givenchy archives while the other is displayed in the Museum of Costume in Madrid.[176] A subsequent London auction of Hepburn’s film wardrobe in December 2009 raised £270,200, including £60,000 for the black Chantilly lace cocktail gown from How to Steal a Million.[177]

References[edit]

- ^ de Hart, Betty (10 July 2017). «Loss of Dutch nationality ex lege: EU law, gender and multiple nationality». Global Citizenship Observatory.

- ^ «REMEMBERING AUDREY HEPBURN: A LOOK BACK AT THE MOVIE ICON’S LIFE IN WORDS AND IMAGES». ¡Hola!. 22 January 2018.

- ^ «Actress Audrey Hepburn dies». HISTORY. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ Walker 1997, p. 9.

- ^ a b Spoto 2006, p. 10.

- ^ a b Matzen 2019, p. 11.

- ^ Segers, Yop. «Heemstra, Aarnoud Jan Anne Aleid baron van (1871–1957)». Historici.nl. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Paris 2001.

- ^ a b c Spoto 2006, p. 3.

- ^ «Ian van Ufford Quarles Obituary». The Times. 29 May 2010. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016.

- ^ a b «Hepburn, Audrey». Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.(subscription required) Archived 2 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Walker 1997, p. 6.

- ^ «The Catalogue».

- ^ «Anna Juliana Franziska Karolina Wels, born in Slovakia». Pitt.edu. Retrieved 4 May 2013.[dead link]

- ^ Walker 1997, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Matzen 2019, p. 10.

- ^ Gitlin 2009, p. 3.

- ^ vrijdag 6 mei 2011, 07u26. «De vijf hoeken van de wereld: Amerika in Elsene». brusselnieuws.be. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- ^ a b Walker 1997, p. 8.

- ^ Spoto 2006, p. 8.

- ^ «‘Dutch Girl’ shows Audrey Hepburn’s wartime courage». Christian Science Monitor. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- ^ Matzen 2019, pp. 11, 15–17.

- ^ Walker 1997, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Walker 1997, p. 14.

- ^ Matzen 2019, pp. 16–18.

- ^ «Famous and Notable People ‘In and Around’ the Elham Valley». Elham.co.uk. Retrieved 4 September 2009.

- ^ Walker 1997, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Moonan, Wendy (22 August 2003). «ANTIQUES; To Daddy Dearest, From Audrey». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- ^ Klein, Edward (5 March 1989). «You Can’t Love Without the Fear of Losing». Parade. pp. 4–6.

«page 1 of 3». Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

«page 2 of 3». Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

«page 3 of 3». Archived from the original on 4 January 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2014. - ^ Cronin, Emily (20 August 2017). «Couture, pearls and a Breakfast at Tiffany’s script: inside the private collection of Audrey Hepburn». The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022.

- ^ Mythe ontkracht: Audrey Hepburn werkte niet voor het verzet, NOS.nl, 17 November 2016 (in Dutch)

- ^ a b Tucker, Reed (9 April 2019). «Hollywood legend Audrey Hepburn was a WWII resistance spy». New York Post. New York, NY.

- ^ Matzen 2019, pp. 146, 148, 149.

- ^ Johnson, Richard (29 October 2018). «Audrey Hepburn reportedly helped resist Nazis in Holland during WWII». Fox News.

- ^ Woodward 2012, p. 36.

- ^ Tichner, Martha (26 November 2006). «Audrey Hepburn». CBS Sunday Morning.

- ^ a b James, Caryn (1993). «Audrey Hepburn, actress, Is Dead at 63». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 January 2007.

- ^ «Eating Tulip Bulbs During World War II». Amsterdam Tulip Museum. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ Macintyre, Ben (6 May 2022). «The Colditz PoW Who Saved Audrey Hepburn». The Times. London. Retrieved 22 October 2022.

- ^ Macintyre, Ben (2022). Colditz: Prisoners of the Castle. London: Viking. ISBN 9780241408520.

- ^ Woodward 2012, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Woodward 2012, p. 52.

- ^ Woodward 2012, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Woodward 2012, p. 53.

- ^ Vermilye 1995, p. 67.

- ^ a b Woodward 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Telegraph, 4 May 2014, ‘I suppose I ended Hepburn’s career’

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn’s Son Remembers Her Life». Larry King Live. 24 December 2003. CNN.

- ^ «Princess Apparent». Time. 7 September 1953. Archived from the original on 14 November 2007.

- ^ Nichols, Mark Audrey Hepburn Goes Back to the Bar, Coronet, November 1956

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn: ‘Roman Holiday’ Star Started as Nightclub Dancer,» 16 December 2020, Variety (recapping 5 July 1950 Variety review of her dance show), retrieved 5 February 2022

- ^ Walker 1997, p. 55.

- ^ «The Silent Village (1951)». BFI. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- ^ Woodward 2012, p. 94.

- ^ Thurman 1999, p. 483.

- ^ a b «History Lesson! Learn How Colette, Audrey Hepburn, Leslie Caron & Vanessa Hudgens Transformed Gigi». Broadway.com. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

- ^ a b «Audrey Is a Hit». Life. 10 December 1951.

- ^ a b «Gigi«. IBDB.com. Internet Broadway Database.

- ^ «The letter that made Audrey Hepburn a star». British Film Institute. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Paris 2001, p. 72.

- ^ Fishgall 2002, p. 173.

- ^ Weiler, A. W. (28 August 1953). «‘Roman Holiday’ at Music Hall Is Modern Fairy Tale Starring Peck and Audrey Hepburn». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011.

- ^ Connolly, Mike. Who Needs Beauty!, Photoplay, January 1954

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn: Behind the sparkle of rhinestones, a diamond’s glow». Time. 7 September 1953. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009.

- ^ «NY Times: Sabrina». Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2009. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (23 September 1954). «Screen: ‘Sabrina’ Bows at Criterion; Billy Wilder Produces and Directs Comedy». The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d e Ringgold, Gene. My Fair Lady – the finest of them all!, Soundstage, December 1964

- ^ «Mel Ferrer». The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ «Hepburn’s Golden Globe nominations and awards». Golden Globes. 14 January 2010. Archived from the original on 8 April 2010.

- ^ Variety magazine. Staff writers. 31 December 1958. «The Nun’s Story».

- ^ Hart, Henry (n.d.). «[The Nun’s Story review]». Films in Review. Archived from the original on 14 February 2006. Retrieved 14 January 2008 – via Audrey1.org (fan site).

- ^ Hepburn quoted in Smyth, J.E. (2014). Fred Zinnemann and the Cinema of Resistance. University Press of Mississippi. p. 174. ISBN 978-1617039645.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (20 March 1959). «Delicate Enchantment of ‘Green Mansions’; Audrey Hepburn Stars in Role of Rima». The New York Times.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (7 April 1960). «Screen: «The Unforgiven’: Huston Film Stars Miss Hepburn, Lancaster». The New York Times.

- ^ Capote 1987, p. 317.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn: Style icon». BBC News. 4 May 2004.

- ^ «The Most Famous Dresses Ever». Glamour. April 2007.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn dress». Hello Magazine. 6 December 2006.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn’s little black dress tops fashion list». The Independent. UK. 17 May 2010.

- ^ Steele 2010, p. 483.

- ^ Kane, Chris. Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Screen Stories, December 1961

- ^ a b Archer, Eugene. With A Little Bit Of Luck And Plenty Of Talent, The New York Times, 1 November 1964

- ^ a b Crowther, Bosley (15 March 1962). «The Screen: New ‘Children’s Hour’: Another Film Version of Play Arrives Shirley MacLaine and Audrey Hepburn Star». The New York Times.

- ^ a b «The Children’s Hour». Variety. 31 December 1960.

- ^ Eastman 1989, pp. 57–58.

- ^ How Awful About Audrey!, Motion Picture, May 1964

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (6 December 1963). «Screen: Audrey Hepburn and Grant in ‘Charade’: Comedy-Melodrama Is at the Music Hall Production Abounds in Ghoulish Humor». The New York Times.

- ^ a b c Eleanor Quin. «Paris When It Sizzles: Overview Article». Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- ^ a b «Paris When It Sizzles». Variety. 1 January 1964.

- ^ My Fair Lady at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ a b Crowther, Bosley (22 October 1964). «Screen: Lots of Chocolates for Miss Eliza Doolittle: ‘My Fair Lady’ Bows at the Criterion». The New York Times.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn obituary». The Daily Telegraph. London. 22 January 1993. Archived from the original on 21 January 2010.

- ^ «Still the Fairest One of All». Time. 30 October 1964.

- ^ «NY Times: My Fair Lady». Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2012. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ Behind Audrey Hepburn and Mel Ferrer’s Breakup, Screenland, December 1967

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (27 October 1967). «The Screen: Audrey Hepburn Stars in ‘Wait Until Dark’«. The New York Times.

- ^ Chicago Sun-Times review by Roger Ebert , 21 April 1976, Retrieved on 7 July 2008

- ^ Canby, Vincent (29 June 1979). «Film: Audrey Hepburn in ‘Bloodline'». The New York Times. C8.

- ^ «Detail view of Movies Page – THEY ALL LAUGHED (1981)». www.afi.com. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ O’Connor, John J. (23 February 1987). «TV Reviews; ABC and NBC Movies on Romance and Crime». The New York Times. Section C, p. 17. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ^ «EGOT winners Taylor Swift is chasing». Daily News. New York City. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ «Classics». United Nations Audiovisual Library. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn». UNICEF. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d «Audrey Hepburn’s UNICEF Field Missions». Retrieved 22 December 2013.

- ^ Hepburn in Moorehead, Caroline, ed. (1990). «Introduction». Betrayal: A Report on Violence Towards Children in Today’s World. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385410977. Archived from the original on 31 August 2012 – via Audrey1.org (fan site).

- ^ Paris, Barry (1996). Audrey Hepburn. New York: Putnam. ISBN 0-399-14056-5. OCLC 34675183.

- ^ «The Din of Silence». Newsweek. 12 October 1992.

- ^ «Was Audrey Hepburn, the Queen of Polyglotism?». news.biharprabha.com. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

- ^ Paris 1996, p. 91.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn’s work for the world’s children honoured». unicef.org. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- ^ «U.N. Hosts Special Session on Children’s Rights». CNN. 7 February 2001.

- ^ Woodward 2012, p. 131.

- ^ Hyams, Joe. Why Audrey Hepburn Was Afraid Of Marriage, Filmland, January 1954

- ^ Woodward 2012, p. 132.

- ^ Kogan, Rick; The Aging of Aquarius, Chicago Tribune, 6/30/96, michaelbutler.com. Retrieved 15 January 2010.

- ^ Walker 1997.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn puts an end to «will she» or «won’t she» rumors by marrying Mel Ferrer!». audreyhepburnlibrary.com [expired domain]. 1954. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010.

- ^ Hepburn Ferrer, Sean (2003). Audrey Hepburn, An Elegant Spirit (1st Atria books hardcover ed.). New York: Atria Books. ISBN 0671024787.

- ^ a b c d Morgan Evans (16 June 2017). «A Timeline of Audrey Hepburn’s Hollywood Love Stories». harpersbazaar.com. Harper’s Bazaar. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ «Mel Ferrer obituary». The Daily Telegraph. 4 June 2008.

- ^ «Hepburn is engaged to Italian psychiatrist», The Globe and Mail; (6 January 1969). Toronto, p. 15.

- ^ «The Private Audrey». People. 1 January 1993. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- ^ Genzlinger, Neil (3 February 2012). «Ben Gazzara, Actor of Stage and Screen, Dies at 81». The New York Times.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn obituary». The Daily Telegraph. 22 January 1993. Archived from the original on 21 January 2010.

- ^ Heatley, Michael (2017). Audrey Hepburn: In words and pictures. Book Sales. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-7858-3534-9.

- ^ Paris 1996, p. 361.

- ^ «Selim Jocelyn, «»The Fairest of All», CR Magazine, Fall 2009″. Crmagazine.org. Archived from the original on 19 April 2010.

- ^ Harris 1994, p. 289.

- ^ «Gregory Peck about Audrey Hepburn». YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021.

- ^ Binder, David (25 January 1993). «Hepburn’s Role As Ambassador Is Paid Tribute». The New York Times.

- ^ «A Gentle Goodbye –Surrounded by the Men She Loved, the Star Was Laid to Rest on a Swiss Hilltop». People. 1 January 1993.

- ^ News Service, N.Y. Times. (25 January 1993). «Hepburn buried in Switzerland». Record-Journal. p. 10.

- ^ a b Christopher, James (12 January 2009). «The best British film actresses of all time». The Times. London.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (10 August 2010). «There’s no reason for Emma Thompson to go lightly on Audrey Hepburn». The Guardian.

- ^ a b Clarke, Cath (19 November 2020). «‘My mother was like a steel fist in a velvet glove’: the real Audrey Hepburn». The Guardian.

- ^ Tynan, William (27 March 2000). «The Audrey Hepburn Story». Time. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007.

- ^ Ramzi, Lilah (16 December 2020). «A New Audrey Hepburn Documentary Reveals the Life Beyond the Glamour». Vogue. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ «Audrey (2020)». Metacritic. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ «New Gap marketing campaign featuring original film footage of Audrey Hepburn helps Gap «Keeps it Simple» this Fall – WBOC-TV 16″. 28 September 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ «New faces on Sgt Pepper album cover for artist Peter Blake’s 80th birthday». The Guardian. 5 October 2016.

- ^ Usborne, Simon (24 February 2013). «Audrey Hepburn advertise Galaxy chocolate bars? Over her dead body!». The Independent. London.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn digitaly reborn for Galaxy». YouTube. 1 March 2013. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021.

- ^ Grossman, Samantha (4 May 2014). «Google Doodle Pays Tribute to Audrey Hepburn». Time.

- ^ Bryant, Kenzie (10 February 2017). «Audrey Hepburn’s Oldest Son in Legal Wrangle with Her Children’s Fund». Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020.

- ^ a b «Proposed Decision Favors Actress’ Eldest Son in Dispute with Charity». Los Angeles, California: KNBC. 19 October 2019. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- ^ a b «Audrey Hepburn’s Son Sean Hepburn Ferrer Vindicated By Court Decision» (Press release). Sean Hepburn Ferrer. 3 December 2019. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ «Sean Hepburn Ferrer». Pseudomyxoma Survivor. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ «Rare Disease Day ® 2015 – Sean Hepburn Ferrer, special ambassador of Rare Disease Day 2014». Rare Disease Day – 28 Feb 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ a b Stempel, Jonathan (5 October 2017). «Audrey Hepburn’s son sues children’s charity over use of mother’s name». Reuters. UK. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2019.

- ^ «Note from Sean Ferrer». Audrey Hepburn official website. n.d. Archived from the original on 12 February 2016.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn Arrives in Berlin» (Press release). Ileana International. 9 March 2009. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 28 July 2020 – via Business Wire.

- ^ a b Bryant, Kenzie (10 February 2017). «Audrey Hepburn’s Oldest Son in Legal Wrangle with Her Children’s Fund». Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 31 May 2020.

- ^ Sean Hepburn Ferrer v. Hollywood For Children, Inc., Court Listener. Free Law Project (District Court, Central District of California 2017-2018). Archived from the original on July 28, 2020.

- ^ Sheridan 2010, p. 95.

- ^ Billson, Anne (29 December 2014). «Audrey Hepburn: a new kind of movie star». The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ a b Hill 2004, p. 78.

- ^ a b c Moseley, Rachel (7 March 2004). «Audrey Hepburn – everybody’s fashion icon». The Guardian.

- ^ Sheridan 2010, p. 93.

- ^ Fu, Joanna. «Style File: Audrey Hepburn». Vogue HK. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ a b Lane, Megan (7 April 2006). «Audrey Hepburn: Why the fuss?». BBC News.

- ^ Naomi Harriet (19 August 2016). «80s Fashion Trends, Reborn!s». La Rue Moderne. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016.

- ^ a b c Collins, Amy Fine (3 February 2014). «When Hubert Met Audrey». Vanity Fair.

- ^ Zarrella, Katharine K. «Hubert de Givenchy & Audrey Hepburn». V Magazine. Archived from the original on 10 May 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- ^ Moseley 2002, p. 39.

- ^ Haria, Sonia (4 August 2012). «Beauty Icon: Givenchy’s L’Interdit«. The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Sheridan 2010, pp. 92–95.

- ^ «Hepburn revival feeding false image?». The Age. Melbourne, Australia. 2 October 2006.

- ^ Harris, Eleanor. Audrey Hepburn, Good Housekeeping, August 1959

- ^ Moseley 2002, pp. 1–10.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn tops beauty poll». BBC News. 31 May 2004.

- ^ Sinclair, Lulu (1 July 2010). «Actress Tops Poll of 20th Century Beauties». Sky.

- ^ Sharkey, Linda (27 April 2015). «Audrey Hepburn is officially Britain’s style icon – 22 years after her death». The Independent.

- ^ Christie’s online catalog. Retrieved 7 December 2006.

- ^ Dahl, Melissa (11 December 2006). «Stylebook: Hepburn gown fetches record price». Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ^ «Marilyn Monroe «subway» dress sells for $4.6 million». Reuters. 19 June 2011.

- ^ «Auction Frenzy over Hepburn dress». BBC News. 5 December 2006.

- ^ «Hepburn’s wardrobe sells for double estimate». Reuters. 9 December 2009.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (20 January 2007). «Audrey Hepburn: Still the Fairest Lady». Time. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn tops beauty poll». BBC. 31 May 2004. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ «AFI’s 50 Greatest American Screen Legends». American Film Institute. Archived from the original on 13 January 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ a b Billson, Anne (29 December 2014). «Audrey Hepburn: a new kind of movie star». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ Cocozza, Paula (1 July 2015). «Audrey Hepburn: Portraits of an Icon review – beautiful, but unrevealing». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ Wilson, Bee (19 June 2015). «The cult of Audrey Hepburn: how can anyone live up to that level of chic?». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 June 2015. Retrieved 10 July 2015.

- ^ Woodward 2012, p. 139.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn’s Fashionable Life in Rome». Vanity Fair. May 2013. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ «The 26th Academy Awards». Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ «Film in 1954». British Academy of Film and Television Arts (BAFTA). Archived from the original on 24 May 2015. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- ^ «Audrey Hepburn». Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015.

- ^ Gitlin 2009, p. 115.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (23 September 1954). «Sabrina (1954) Screen: ‘Sabrina’ Bows at Criterion; Billy Wilder Produces and Directs Comedy». The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 July 2015. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Woodward 2012, p. 393.

- ^ Gitlin 2009, p. 116.

- ^ «BAFTA Awards Search – Audrey Hepburn». bafta.org. British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ Marx, Andy (13 January 1993). «Hepburn, Taylor get Hersholt». Variety. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

- ^ King, Susan (12 December 2013). «Audrey Hepburn’s 1953 ‘Roman Holiday’ an enchanting fairy tale». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 23 October 2021.

Bibliography[edit]

- Capote, Truman (1987). Truman Capote: Conversations (Literary Conversations Series) (Edited by M. Thomas Inge). Univ Pr of Mississippi; First Edition (1 February 1987). ISBN 0878052747.

- Eastman, John (1989). Retakes: Behind the Scenes of 500 Classic Movies. Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-35399-4.

- Ferrer, Sean (2005). Audrey Hepburn, an Elegant Spirit. New York: Atria. ISBN 978-0-671-02479-6.

- Fishgall, Gary (2002). Gregory Peck: A Biography. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-684-85290-X.

- Gitlin, Martin (2009). Audrey Hepburn: A Biography. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-35945-3.

- Givenchy, Hubert de (2007). Audrey Hepburn. London: Pavilion. ISBN 978-1-86205-775-3.

- Harris, Warren G. (1994). Audrey Hepburn: A Biography. Wheeler Pub. ISBN 978-1-56895-156-0.

- Hill, Daniel Delis (2004). As Seen in Vogue: A Century of American Fashion in Advertising. Texas Tech University Press. ISBN 9780896725348.

- Matzen, Robert (2019). Dutch Girl: Audrey Hepburn and World War II. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: GoodKnight Books (Paladin). ISBN 978-1-7322735-3-5.

- Moseley, Rachel (2002). Growing Up with Audrey Hepburn: Text, Audience, Resonance. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6310-7.

- Paris, Barry (2001) [1996]. Audrey Hepburn. Berkley Books. ISBN 978-0-425-18212-3.

- Sheridan, Jayne (2010). Fashion, Media, Promotion: The New Black Magic. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-9421-1.

- Spoto, Donald (2006). Enchantment: The Life of Audrey Hepburn. Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-307-23758-3.

- Steele, Valerie (2010). The Berg Companion to Fashion. Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84788-592-0.

- Thurman, Judith (1999). Secrets of the Flesh: A Life of Colette. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-3945-8872-8.

- Vermilye, Jerry (1995). The Complete Films of Audrey Hepburn. New York: Citadel Press. ISBN 0-8065-1598-8.

- Walker, Alexander (1997) [1994]. Audrey, Her Real Story. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-18046-2.

- Wilson, Julie (14 March 2011). «A new kind of star is born: Audrey Hepburn and the global governmentalisation of female stardom». Celebrity Studies. Informa UK Limited. 2 (1): 56–68. doi:10.1080/19392397.2011.544163. ISSN 1939-2397. S2CID 144559753.

- Woodward, Ian (31 May 2012). Audrey Hepburn: Fair Lady of the Screen. Ebury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4481-3293-5.

Further reading[edit]

- Brizel, Scott (18 November 2009). Audrey Hepburn: International Cover Girl. Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-6820-4.

- Byczynski, Stuart J. (1 January 1998). Audrey Hepburn: A Secret Life. Brunswick Publishing Corporation. ISBN 978-1-55618-168-9.

- Cheshire, Ellen (19 October 2011). Audrey Hepburn. Perseus Books Group. ISBN 978-1-84243-547-2.

- Hepburn-Ferrer, Sean (5 April 2005). Audrey Hepburn, An Elegant Spirit. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-02479-6.

- Hofstede, David (31 August 1994). Audrey Hepburn: a bio-bibliography. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313289095.

- Karney, Robyn (1995). Audrey Hepburn: A Star Danced. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55970-300-0.

- Keogh, Pamela Clarke (2009). Audrey Style. Aurum Press, Limited. ISBN 978-1-84513-490-7.

- Kidney, Christine (1 February 2010). Audrey Hepburn. Pulteney Press. ISBN 978-1-906734-57-2.

- Life: Remembering Audrey 15 Years Later. Life Magazine, Time Inc. Home Entertainment. 1 August 2008. ISBN 978-1-60320-536-8.

- Marsh, June (June 2013). Audrey Hepburn in Hats. Reel Art Press. ISBN 978-1-909526-00-6.

- Maychick, Diana (1 May 1996). Audrey Hepburn: An Intimate Portrait. Carol Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8065-8000-5.

- Meyer-Stabley, Bertrand (2010). La Véritable Audrey Hepburn (in French). Pygmalion. ISBN 978-2-7564-0321-2.

- Morley, Sheridan (1993). Audrey Hepburn: A Celebration. Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-1-85793-136-5.

- Nirwing, Sandy (26 January 2006). An American in Paris: Audrey Hepburn and the City of Light – A historical analysis of genre cinema & gender roles. GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-638-46087-3.

- Nourmand, Tony (2006). Audrey Hepburn: The Paramount Years. Boxtree. ISBN 978-0-7522-2603-3.

- Paris, Barry (11 January 2002). Audrey Hepburn. Berkley Pub Group. ISBN 978-0-425-18212-3.

- Ricci, Stefania (June 1999). Audrey Hepburn: una donna, lo stile (in Italian). Leonardo Arte. ISBN 978-88-7813-550-5.

- Wasson, Sam (22 June 2010). Fifth Avenue, 5 A.M.: Audrey Hepburn, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, and The Dawn of the Modern Woman. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-200013-2.

- Yapp, Nick (20 November 2009). Audrey Hepburn. Endeavour. ISBN 9781873913109.

External links[edit]

|

Audrey Hepburn |

|

|---|---|

Hepburn in 1956 |

|

| Born |

Audrey Kathleen Ruston 4 May 1929 Ixelles, Brussels, Belgium |

| Died | 20 January 1993 (aged 63)

Tolochenaz, Vaud, Switzerland |

| Resting place | Tolochenaz Cemetery, Tolochenaz |

| Nationality | British |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active |

|

| Notable work | Full list |

| Spouses |

Mel Ferrer (m. 1954; div. 1968) Andrea Dotti (m. 1969; div. 1982) |

| Partner | Robert Wolders (1980–1993; her death) |

| Children | 2, including Sean |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Goodwill Ambassador for UNICEF | |

| In office 1989–1993 |

|

| Signature | |

Audrey Hepburn (born Audrey Kathleen Ruston; 4 May 1929 – 20 January 1993) was a British[a] actress and humanitarian. Recognised as both a film and fashion icon, she was ranked by the American Film Institute as the third-greatest female screen legend from the Classical Hollywood cinema and was inducted into the International Best Dressed List Hall of Fame.