| Полоний | |

|---|---|

| Серебристо-белый мягкий металл | |

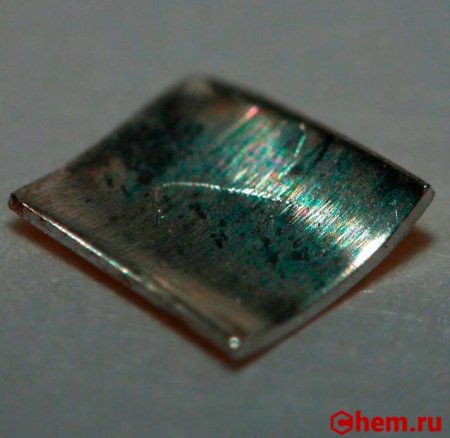

Тонкая плёнка металлического полония на диске из нержавеющей стали |

|

| Название, символ, номер | Полоний / Polonium (Po), 84 |

| Атомная масса (молярная масса) |

208,9824 а. е. м. (г/моль) |

| Электронная конфигурация | [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6s2 6p4 |

| Радиус атома | 176 пм |

| Ковалентный радиус | 146 пм |

| Радиус иона | (+6e) 67 пм |

| Электроотрицательность | 2,3 (шкала Полинга) |

| Электродный потенциал | Po ← Po3+ 0,56 В Po ← Po2+ 0,65 В |

| Степени окисления | –2, +2, +4, +6 |

| Энергия ионизации (первый электрон) |

813,1 (8,43) кДж/моль (эВ) |

| Плотность (при н. у.) | 9,196 г/см3 г/см³ |

| Температура плавления | 527 K (254 °C, 489 °F) |

| Температура кипения | 1235 K (962 °C, 1764 °F)] |

| Уд. теплота плавления | 10 кДж/моль |

| Уд. теплота испарения | 102,9 кДж/моль |

| Молярная теплоёмкость | 26,4 Дж/(K·моль) |

| Молярный объём | 22,7 см³/моль |

| Структура решётки | кубическая |

| Параметры решётки | 3.35 Å |

| Номер CAS | 7440-08-6 |

Полоний — радиоактивный химический элемент 16-й группы (по устаревшей классификации — главной подгруппы VI группы), 6-го периода в периодической системе Д. И. Менделеева, с атомным номером 84, обозначается символом Po (лат. Polonium). Относится к группе халькогенов. При нормальных условиях представляет собой мягкий радиоактивный металл серебристо-белого цвета.

Содержание

- 1 История и происхождение названия

- 2 Нахождение в природе

- 3 Свойства

- 4 Изотопы

- 5 Получение

- 6 Применение

- 7 Токсичность

- 8 Случаи отравления полонием-210

- 9 Содержание полония в продуктах

История и происхождение названия

Элемент открыт в 1898 году супругами Пьером Кюри и Марией Склодовской-Кюри в урановой смоляной руде. Об открытии они впервые сообщили 18 июля на заседании Парижской академии наук в докладе под названием «О новом радиоактивном веществе, содержащемся в смоляной обманке». Элемент был назван в честь родины Марии Склодовской-Кюри — Польши (лат. Polonia).

В 1902 году немецкий учёный Вильгельм Марквальд открыл новый элемент. Он назвал его радиотеллур. Кюри, прочтя заметку об открытии, сообщила, что это — элемент полоний, открытый ими четырьмя годами ранее. Марквальд не согласился с такой оценкой, заявив, что полоний и радиотеллур — разные элементы. После ряда экспериментов с элементом супруги Кюри доказали, что полоний и радиотеллур обладают одним и тем же периодом полураспада. Марквальд был вынужден признать свою ошибку.

Первый образец полония, содержащий 0,1 мг этого элемента, был выделен в 1910 году.

Нахождение в природе

Радионуклиды полония входят в состав естественных радиоактивных рядов:

210Po (Т1/2 = 138,376 суток), 218Po (Т1/2 = 3,10 мин) и 214Po (Т1/2 = 1,643⋅10−4 с) — в ряд 238U;

216Po (Т1/2 = 0,145 с) и 212Po (Т1/2 = 2,99⋅10−7 с) — в ряд Th;

215Po (Т1/2 = 1,781⋅10−3 с) и 211Po(Т1/2 = 0,516 с) — в ряд 235U.

Поэтому полоний всегда присутствует в урановых и ториевых минералах. Равновесное содержание полония в земной коре — около 2⋅10−14% по массе.

Свойства

Полоний — мягкий серебристо-белый радиоактивный металл.

Металлический полоний быстро окисляется на воздухе. Известны диоксид полония (PoO2)x и монооксид полония PoO. С галогенами образует тетрагалогениды. При действии кислот переходит в раствор с образованием катионов Ро2+ розового цвета:

-

- Po + 2HCl → PoCl2 + H2↑

При растворении полония в соляной кислоте в присутствии магния образуется полоноводород:

-

- Po + Mg + 2HCl → MgCl2 + H2Po

который при комнатной температуре находится в жидком состоянии (от −36,1 до 35,3 °C)

В индикаторных количествах получены кислотный триоксид полония PoO3 и соли полониевой кислоты, не существующей в свободном состоянии — полонаты K2PoO4. Образует галогениды состава PoX2, PoX4 и PoX6. Подобно теллуру полоний способен с рядом металлов образовывать химические соединения — полониды.

Полоний является единственным химическим элементом, который при низкой температуре образует одноатомную простую кубическую кристаллическую решётку.

Изотопы

Основная статья: Изотопы полония

На начало 2006 года известны 33 изотопа полония в диапазоне массовых чисел от 188 до 220. Кроме того, известны 10 метастабильных возбуждённых состояний изотопов полония. Стабильных изотопов не имеет. Наиболее долгоживущие изотопы, 209Po и 208Po имеют периоды полураспада 125 и 2,9 года соответственно. Некоторые изотопы полония, входящие в радиоактивные ряды урана и тория, имеют собственные наименования, которые сейчас в основном рассматриваются как устаревшие:

| Изотоп | Название | Обозначение | Радиоактивный ряд |

|---|---|---|---|

| 210Po | Радий F | RaF | 238U |

| 211Po | Актиний C’ | AcC’ | 235U |

| 212Po | Торий C’ | ThC’ | 232Th |

| 214Po | Радий C’ | RaC’ | 238U |

| 215Po | Актиний A | AcA | 235U |

| 216Po | Торий A | ThA | 232Th |

| 218Po | Радий A | RaA | 238U |

Получение

На практике в граммовых количествах нуклид полония 210Po синтезируют искусственно, облучая металлический 209Bi тепловыми нейтронами в ядерных реакторах. Получившийся 210Bi за счёт β-распада превращается в 210Po. При облучении того же изотопа висмута протонами по реакции

- 209Bi + p → 209Po + n

образуется самый долгоживущий изотоп полония 209Po.

В реакторах с жидкометаллическим носителем в качестве теплоносителя может применяться эвтектика свинец-висмут. Такой реактор, в частности, был установлен на подводной лодке К-27. В активной зоне реактора висмут может переходить в полоний.

Микроколичества полония извлекают из отходов переработки урановых руд. Выделяют полоний экстракцией, ионным обменом, хроматографией и возгонкой.

Металлический Po получают термическим разложением в вакууме сульфида PoS или диоксида (PoO2)x при 500 °C.

Более 95 % мирового производства полония-210 приходится на Россию, однако практически весь он поставляется в США, где используется в основном для производства промышленных и бытовых антистатических ионизаторов воздуха.

На 2006 год, по утверждению британского учёного и писателя Джона Эмсли, в год производилось около 100 грамм 210Po.

- Стоимость

По данным британских экспертов, микроскопические дозы полония-210 стоят миллионы долларов США. С другой стороны, согласно утверждению радиохимика, д.х.н. Б.Жуйкова, получаемый из висмута полоний-210 очень дешёв. Согласно данным на 2006 год за производство 9,6 граммов полония-210 заводу «Авангард» платили порядка 10 миллионов рублей, что сопоставимо со стоимостью трития. Однако, американская компания United Nuclear, получающая изотоп из России, на 2006 год продавала образцы по цене $69, утверждая, что для накопления смертельной дозы потребовалось бы более $1 миллиона.

Применение

Полоний-210 в сплавах с бериллием и бором применяется для изготовления компактных и очень мощных нейтронных источников, практически не создающих γ-излучения (но короткоживущих ввиду малого времени жизни 210Po: Т1/2 = 138,376 суток) — альфа-частицы полония-210 рождают нейтроны на ядрах бериллия или бора в (α, n)-реакции. Это герметичные металлические ампулы, в которые заключена покрытая полонием-210 керамическая таблетка из карбида бора или карбида бериллия. Такие нейтронные источники легки и портативны, совершенно безопасны в работе и очень надёжны. Например, советский нейтронный источник ВНИ-2 представляет собой латунную ампулу диаметром два и высотой четыре сантиметра, ежесекундно излучающую до 90 миллионов нейтронов.

Полоний-210 часто применяется для ионизации газов (в частности, воздуха). В первую очередь ионизация воздуха необходима для борьбы со статическим электричеством (на производстве, при обращении с особо чувствительной аппаратурой). Например, для прецизионной оптики изготавливаются кисточки удаления пыли. Для окраски автомобилей в гаражах используются пульверизаторы с подачей воздуха, проходящего через антистатический ионизатор с полонием («ионную пушку»). Другое, уже ушедшее в прошлое применение эффекта ионизации газа — в электродных сплавах автомобильных свечей зажигания для уменьшения напряжения возникновения искры.

Важной областью применения полония-210 является его использование в виде сплавов со свинцом, иттрием или самостоятельно для производства мощных и весьма компактных источников тепла для автономных установок, например, космических. Один кубический сантиметр полония-210 выделяет около 1320 Вт тепла. Эта мощность весьма велика, она легко приводит полоний в расплавленное состояние, поэтому его сплавляют, например, со свинцом. Хотя эти сплавы имеют заметно меньшую энергоплотность (150 Вт/см³), тем не менее, они более удобны к применению и безопасны, так как полоний-210 испускает почти исключительно альфа-частицы, а их проникающая способность и длина пробега в плотном веществе минимальны. Например, у советских самоходных аппаратов космической программы «Луноход» для обогрева приборного отсека применялся полониевый обогреватель.

Полоний-210 может послужить в сплаве с лёгким изотопом лития (6Li) веществом, которое способно существенно снизить критическую массу ядерного заряда и послужить своего рода ядерным детонатором. Кроме того, полоний пригоден для создания компактных «грязных бомб» и удобен для скрытной транспортировки, так как практически не испускает гамма-излучения. Изотоп испускает гамма-кванты с энергией 803 кэВ с выходом только 0,001 % на распад.

Полоний является стратегическим металлом, должен очень строго учитываться, и его хранение должно быть под контролем государства ввиду угрозы ядерного терроризма.

Токсичность

Полоний-210 чрезвычайно токсичен, радиотоксичен и канцерогенен, имеет период полураспада 138 дней и 9 часов. В 4 триллиона раз токсичнее синильной кислоты. Его удельная активность (166 ТБк/г) настолько велика, что, хотя он излучает только альфа-частицы, брать его руками нельзя, поскольку результатом будет лучевое поражение кожи и, возможно, всего организма: полоний довольно легко проникает внутрь сквозь кожные покровы. Он опасен и на расстоянии, превышающем длину пробега альфа-частиц, так как его соединения саморазогреваются и переходят в аэрозольное состояние. ПДК в водоёмах и в воздухе рабочих помещений 11,1⋅10−3 Бк/л и 7,41⋅10−3 Бк/м³. Поэтому работают с полонием-210 только в герметичных боксах.

Положительно заряженные альфа-частицы, излучаемые полонием, не проходят через кожу, однако при попадании полония внутрь организма, — если его проглотить или вдохнуть, — альфа-частицы необратимо разрушают внутренние органы и ткани, что зачастую приводит к гибели организма.

По оценке специалистов летальная доза полония-210 для взрослого человека — оценивается в пределах от 0,1—0,3 ГБк (0,6—2 мкг) при попадании изотопа в организм через лёгкие, до 1—3 ГБк (6—18 мкг) при попадании в организм через пищеварительный тракт.

Более долгоживущие полоний-208 (период полураспада 2,898 года) и полоний-209 (период полураспада 103 года) обладают несколько меньшей радиотоксичностью на единицу веса, обратно пропорционально периоду полураспада. Сведений о радиотоксичности других, короткоживущих изотопов полония мало. В организме человека полоний ведёт себя подобно своим химическим гомологам, селену и теллуру, концентрируется в печени, почках, селезёнке и костном мозге. Период полувыведения из организма − от 30 до 50 дней, выделяется в основном через почки. Есть сообщения об успешном использовании 2,3-димеркаптопропанола для выведения полония из организма крыс — 90 % животных, которым внутривенно вводилась смертельная доза полония-210 (9 нг/кг веса), выжили, тогда как в контрольной группе все крысы погибли в течение полутора месяцев.

Случаи отравления полонием-210

- Смерть Александра Литвиненко в 2006 году, который скончался в результате отравления полонием-210.

- Полоний был обнаружен в личных вещах Ясира Арафата, который скончался в 2004 году. Проведена эксгумация тела. Первоначально швейцарская сторона международной комиссии подтвердила факт отравления полонием. Однако позже согласилась с выводами российской и французской стороны об отсутствии доказательств отравления.

Содержание полония в продуктах

Полоний-210 в небольших количествах находится в природе и накапливается табаком, вследствие чего является одним из заметных факторов, который наносит вред здоровью курильщика. Другие природные изотопы полония распадаются очень быстро, поэтому не успевают накапливаться в табаке. «Производители табака обнаружили этот элемент более 40 лет назад, попытки удалить его были безуспешны», — говорится в статье 2008 года исследователей из американского Стэнфордского университета и клиники Майо в Рочестере.

|

Периодическая система химических элементов Д. И. Менделеева |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Электрохимический ряд активности металлов |

|---|

|

Eu, Sm, Li, Cs, Rb, K, Ra, Ba, Sr, Ca, Na, Ac, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Pm, Gd, Tb, Mg, Y, Dy, Am, Ho, Er, Tm, Lu, Sc, Pu, |

|

Соединения полония |

|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polonium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (pə-LOH-nee-əm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allotropes | α, β | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass number | [209] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polonium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 84 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 16 (chalcogens) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6s2 6p4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 527 K (254 °C, 489 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1235 K (962 °C, 1764 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | α-Po: 9.196 g/cm3 β-Po: 9.398 g/cm3 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | ca. 13 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 102.91 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.4 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, +2, +4, +5,[1] +6 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 168 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 140±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 197 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of polonium |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | from decay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | cubic

α-Po |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | rhombohedral

β-Po |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 23.5 µm/(m⋅K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 20 W/(m⋅K) (?) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | α-Po: 0.40 µΩ⋅m (at 0 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | nonmagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-08-6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Polonia, Latin for Poland, homeland of Marie Curie | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Pierre and Marie Curie (1898) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First isolation | Willy Marckwald (1902) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Isotopes of polonium

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Polonium is a chemical element with the symbol Po and atomic number 84. A rare and highly radioactive metal with no stable isotopes, polonium is a chalcogen and is chemically similar to selenium and tellurium, though its metallic character resembles that of its horizontal neighbors in the periodic table: thallium, lead, and bismuth. Due to the short half-life of all its isotopes, its natural occurrence is limited to tiny traces of the fleeting polonium-210 (with a half-life of 138 days) in uranium ores, as it is the penultimate daughter of natural uranium-238. Though slightly longer-lived isotopes exist, they are much more difficult to produce. Today, polonium is usually produced in milligram quantities by the neutron irradiation of bismuth. Due to its intense radioactivity, which results in the radiolysis of chemical bonds and radioactive self-heating, its chemistry has mostly been investigated on the trace scale only.

Polonium was discovered in July 1898 by Marie Skłodowska-Curie and Pierre Curie, when it was extracted from the uranium ore pitchblende and identified solely by its strong radioactivity: it was the first element to be so discovered. Polonium was named after Marie Curie’s homeland of Poland. Polonium has few applications, and those are related to its radioactivity: heaters in space probes, antistatic devices, sources of neutrons and alpha particles, and poison. It is extremely dangerous to humans.

Characteristics[edit]

210Po is an alpha emitter that has a half-life of 138.4 days; it decays directly to its stable daughter isotope, 206Pb. A milligram (5 curies) of 210Po emits about as many alpha particles per second as 5 grams of 226Ra,[3] which means it is 5,000 times more radioactive than radium. A few curies (1 curie equals 37 gigabecquerels, 1 Ci = 37 GBq) of 210Po emit a blue glow which is caused by ionisation of the surrounding air.

About one in 100,000 alpha emissions causes an excitation in the nucleus which then results in the emission of a gamma ray with a maximum energy of 803 keV.[4][5]

Solid state form[edit]

The alpha form of solid polonium.

Polonium is a radioactive element that exists in two metallic allotropes. The alpha form is the only known example of a simple cubic crystal structure in a single atom basis at STP, with an edge length of 335.2 picometers; the beta form is rhombohedral.[6][7][8] The structure of polonium has been characterized by X-ray diffraction[9][10] and electron diffraction.[11]

210Po (in common with 238Pu[citation needed]) has the ability to become airborne with ease: if a sample is heated in air to 55 °C (131 °F), 50% of it is vaporized in 45 hours to form diatomic Po2 molecules, even though the melting point of polonium is 254 °C (489 °F) and its boiling point is 962 °C (1,764 °F).[12][13][1]

More than one hypothesis exists for how polonium does this; one suggestion is that small clusters of polonium atoms are spalled off by the alpha decay.[14]

Chemistry[edit]

The chemistry of polonium is similar to that of tellurium, although it also shows some similarities to its neighbor bismuth due to its metallic character. Polonium dissolves readily in dilute acids but is only slightly soluble in alkalis. Polonium solutions are first colored in pink by the Po2+ ions, but then rapidly become yellow because alpha radiation from polonium ionizes the solvent and converts Po2+ into Po4+. As polonium also emits alpha-particles after disintegration so this process is accompanied by bubbling and emission of heat and light by glassware due to the absorbed alpha particles; as a result, polonium solutions are volatile and will evaporate within days unless sealed.[15][16] At pH about 1, polonium ions are readily hydrolyzed and complexed by acids such as oxalic acid, citric acid, and tartaric acid.[17]

Compounds[edit]

Polonium has no common compounds, and almost all of its compounds are synthetically created; more than 50 of those are known.[18] The most stable class of polonium compounds are polonides, which are prepared by direct reaction of two elements. Na2Po has the antifluorite structure, the polonides of Ca, Ba, Hg, Pb and lanthanides form a NaCl lattice, BePo and CdPo have the wurtzite and MgPo the nickel arsenide structure. Most polonides decompose upon heating to about 600 °C, except for HgPo that decomposes at ~300 °C and the lanthanide polonides, which do not decompose but melt at temperatures above 1000 °C. For example, the polonide of praseodymium (PrPo) melts at 1250 °C, and that of thulium (TmPo) melts at 2200 °C.[19] PbPo is one of the very few naturally occurring polonium compounds, as polonium alpha decays to form lead.[20]

Polonium hydride (PoH

2) is a volatile liquid at room temperature prone to dissociation; it is thermally unstable.[19] Water is the only other known hydrogen chalcogenide which is a liquid at room temperature; however, this is due to hydrogen bonding. The three oxides, PoO, PoO2 and PoO3, are the products of oxidation of polonium.[21]

Halides of the structure PoX2, PoX4 and PoF6 are known. They are soluble in the corresponding hydrogen halides, i.e., PoClX in HCl, PoBrX in HBr and PoI4 in HI.[22] Polonium dihalides are formed by direct reaction of the elements or by reduction of PoCl4 with SO2 and with PoBr4 with H2S at room temperature. Tetrahalides can be obtained by reacting polonium dioxide with HCl, HBr or HI.[23]

Other polonium compounds include potassium polonite as a polonite, polonate, acetate, bromate, carbonate, citrate, chromate, cyanide, formate, (II) and (IV) hydroxides, nitrate, selenate, selenite, monosulfide, sulfate, disulfate and sulfite.[22][24]

A limited organopolonium chemistry is known, mostly restricted to dialkyl and diaryl polonides (R2Po), triarylpolonium halides (Ar3PoX), and diarylpolonium dihalides (Ar2PoX2).[25][26] Polonium also forms soluble compounds with some chelating agents, such as 2,3-butanediol and thiourea.[25]

| Formula | Color | m.p. (°C) | Sublimation temp. (°C) |

Symmetry | Pearson symbol | Space group | No | a (pm) | b(pm) | c(pm) | Z | ρ (g/cm3) | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PoO | black | ||||||||||||

| PoO2 | pale yellow | 500 (dec.) | 885 | fcc | cF12 | Fm3m | 225 | 563.7 | 563.7 | 563.7 | 4 | 8.94 | [28] |

| PoH2 | -35.5 | ||||||||||||

| PoCl2 | dark ruby red | 355 | 130 | orthorhombic | oP3 | Pmmm | 47 | 367 | 435 | 450 | 1 | 6.47 | [29] |

| PoBr2 | purple-brown | 270 (dec.) | [30] | ||||||||||

| PoCl4 | yellow | 300 | 200 | monoclinic | [29] | ||||||||

| PoBr4 | red | 330 (dec.) | fcc | cF100 | Fm3m | 225 | 560 | 560 | 560 | 4 | [30] | ||

| PoI4 | black | [31] |

Isotopes[edit]

Polonium has 42 known isotopes, all of which are radioactive. They have atomic masses that range from 186 to 227 u. 210Po (half-life 138.376 days) is the most widely available and is made via neutron capture by natural bismuth. The longer-lived 209Po (half-life 125.2±3.3 years, longest-lived of all polonium isotopes)[32] and 208Po (half-life 2.9 years) can be made through the alpha, proton, or deuteron bombardment of lead or bismuth in a cyclotron.[33]

History[edit]

Tentatively called «radium F», polonium was discovered by Marie and Pierre Curie in July 1898,[34][35] and was named after Marie Curie’s native land of Poland (Latin: Polonia).[36][37] Poland at the time was under Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian partition, and did not exist as an independent country. It was Curie’s hope that naming the element after her native land would publicize its lack of independence.[38] Polonium may be the first element named to highlight a political controversy.[38]

This element was the first one discovered by the Curies while they were investigating the cause of pitchblende radioactivity. Pitchblende, after removal of the radioactive elements uranium and thorium, was more radioactive than the uranium and thorium combined. This spurred the Curies to search for additional radioactive elements. They first separated out polonium from pitchblende in July 1898, and five months later, also isolated radium.[15][34][39] German scientist Willy Marckwald successfully isolated 3 milligrams of polonium in 1902, though at the time he believed it was a new element, which he dubbed «radio-tellurium», and it was not until 1905 that it was demonstrated to be the same as polonium.[40][41]

In the United States, polonium was produced as part of the Manhattan Project’s Dayton Project during World War II. Polonium and beryllium were the key ingredients of the ‘Urchin’ initiator at the center of the bomb’s spherical pit.[42] ‘Urchin’ initiated the nuclear chain reaction at the moment of prompt-criticality to ensure that the weapon did not fizzle. ‘Urchin’ was used in early U.S. weapons; subsequent U.S. weapons utilized a pulse neutron generator for the same purpose.[42]

Much of the basic physics of polonium was classified until after the war. The fact that it was used as an initiator was classified until the 1960s.[43]

The Atomic Energy Commission and the Manhattan Project funded human experiments using polonium on five people at the University of Rochester between 1943 and 1947. The people were administered between 9 and 22 microcuries (330 and 810 kBq) of polonium to study its excretion.[44][45][46]

Occurrence and production[edit]

Polonium is a very rare element in nature because of the short half-lives of all its isotopes. Seven isotopes occur in traces as decay products: 210Po, 214Po, and 218Po occur in the decay chain of 238U; 211Po and 215Po occur in the decay chain of 235U; 212Po and 216Po occur in the decay chain of 232Th. Of these, 210Po is the only isotope with a half-life longer than 3 minutes.[47]

Polonium can be found in uranium ores at about 0.1 mg per metric ton (1 part in 1010),[48][49] which is approximately 0.2% of the abundance of radium. The amounts in the Earth’s crust are not harmful. Polonium has been found in tobacco smoke from tobacco leaves grown with phosphate fertilizers.[50][51][52]

Because it is present in small concentrations, isolation of polonium from natural sources is a tedious process. The largest batch of the element ever extracted, performed in the first half of the 20th century, contained only 40 Ci (1.5 TBq) (9 mg) of polonium-210 and was obtained by processing 37 tonnes of residues from radium production.[53] Polonium is now usually obtained by irradiating bismuth with high-energy neutrons or protons.[15][54]

In 1934, an experiment showed that when natural 209Bi is bombarded with neutrons, 210Bi is created, which then decays to 210Po via beta-minus decay. The final purification is done pyrochemically followed by liquid-liquid extraction techniques.[55] Polonium may now be made in milligram amounts in this procedure which uses high neutron fluxes found in nuclear reactors.[54] Only about 100 grams are produced each year, practically all of it in Russia, making polonium exceedingly rare.[56][57]

This process can cause problems in lead-bismuth based liquid metal cooled nuclear reactors such as those used in the Soviet Navy’s K-27. Measures must be taken in these reactors to deal with the unwanted possibility of 210Po being released from the coolant.[58][59]

The longer-lived isotopes of polonium, 208Po and 209Po, can be formed by proton or deuteron bombardment of bismuth using a cyclotron. Other more neutron-deficient and more unstable isotopes can be formed by the irradiation of platinum with carbon nuclei.[60]

Applications[edit]

Polonium-based sources of alpha particles were produced in the former Soviet Union.[61] Such sources were applied for measuring the thickness of industrial coatings via attenuation of alpha radiation.[62]

Because of intense alpha radiation, a one-gram sample of 210Po will spontaneously heat up to above 500 °C (932 °F) generating about 140 watts of power. Therefore, 210Po is used as an atomic heat source to power radioisotope thermoelectric generators via thermoelectric materials.[3][15][63][64] For example, 210Po heat sources were used in the Lunokhod 1 (1970) and Lunokhod 2 (1973) Moon rovers to keep their internal components warm during the lunar nights, as well as the Kosmos 84 and 90 satellites (1965).[61][65]

The alpha particles emitted by polonium can be converted to neutrons using beryllium oxide, at a rate of 93 neutrons per million alpha particles.[63] Po-BeO mixtures are used as passive neutron sources with a gamma-ray-to-neutron production ratio of 1.13 ± 0.05, lower than for nuclear fission-based neutron sources.[66] Examples of Po-BeO mixtures or alloys used as neutron sources are a neutron trigger or initiator for nuclear weapons[15][67] and for inspections of oil wells. About 1500 sources of this type, with an individual activity of 1,850 Ci (68 TBq), had been used annually in the Soviet Union.[68]

Polonium was also part of brushes or more complex tools that eliminate static charges in photographic plates, textile mills, paper rolls, sheet plastics, and on substrates (such as automotive) prior to the application of coatings.[69] Alpha particles emitted by polonium ionize air molecules that neutralize charges on the nearby surfaces.[70][71] Some anti-static brushes contain up to 500 microcuries (20 MBq) of 210Po as a source of charged particles for neutralizing static electricity.[72] In the US, devices with no more than 500 μCi (19 MBq) of (sealed) 210Po per unit can be bought in any amount under a «general license»,[73] which means that a buyer need not be registered by any authorities. Polonium needs to be replaced in these devices nearly every year because of its short half-life; it is also highly radioactive and therefore has been mostly replaced by less dangerous beta particle sources.[3]

Tiny amounts of 210Po are sometimes used in the laboratory and for teaching purposes—typically of the order of 4–40 kBq (0.11–1.08 μCi), in the form of sealed sources, with the polonium deposited on a substrate or in a resin or polymer matrix—are often exempt from licensing by the NRC and similar authorities as they are not considered hazardous. Small amounts of 210Po are manufactured for sale to the public in the United States as «needle sources» for laboratory experimentation, and they are retailed by scientific supply companies. The polonium is a layer of plating which in turn is plated with a material such as gold, which allows the alpha radiation (used in experiments such as cloud chambers) to pass while preventing the polonium from being released and presenting a toxic hazard.[citation needed]

Polonium spark plugs were marketed by Firestone from 1940 to 1953. While the amount of radiation from the plugs was minuscule and not a threat to the consumer, the benefits of such plugs quickly diminished after approximately a month because of polonium’s short half-life and because buildup on the conductors would block the radiation that improved engine performance. (The premise behind the polonium spark plug, as well as Alfred Matthew Hubbard’s prototype radium plug that preceded it, was that the radiation would improve ionization of the fuel in the cylinder and thus allow the motor to fire more quickly and efficiently.)[74][75]

Biology and toxicity[edit]

Overview[edit]

Polonium can be hazardous and has no biological role.[15] By mass, polonium-210 is around 250,000 times more toxic than hydrogen cyanide (the LD50 for 210Po is less than 1 microgram for an average adult (see below) compared with about 250 milligrams for hydrogen cyanide[76]). The main hazard is its intense radioactivity (as an alpha emitter), which makes it difficult to handle safely. Even in microgram amounts, handling 210Po is extremely dangerous, requiring specialized equipment (a negative pressure alpha glove box equipped with high-performance filters), adequate monitoring, and strict handling procedures to avoid any contamination. Alpha particles emitted by polonium will damage organic tissue easily if polonium is ingested, inhaled, or absorbed, although they do not penetrate the epidermis and hence are not hazardous as long as the alpha particles remain outside the body. Wearing chemically resistant and intact gloves is a mandatory precaution to avoid transcutaneous diffusion of polonium directly through the skin. Polonium delivered in concentrated nitric acid can easily diffuse through inadequate gloves (e.g., latex gloves) or the acid may damage the gloves.[77]

Polonium does not have toxic chemical properties.[78]

It has been reported that some microbes can methylate polonium by the action of methylcobalamin.[79][80] This is similar to the way in which mercury, selenium, and tellurium are methylated in living things to create organometallic compounds. Studies investigating the metabolism of polonium-210 in rats have shown that only 0.002 to 0.009% of polonium-210 ingested is excreted as volatile polonium-210.[81]

Acute effects[edit]

The median lethal dose (LD50) for acute radiation exposure is about 4.5 Sv.[82] The committed effective dose equivalent 210Po is 0.51 µSv/Bq if ingested, and 2.5 µSv/Bq if inhaled.[83] A fatal 4.5 Sv dose can be caused by ingesting 8.8 MBq (240 μCi), about 50 nanograms (ng), or inhaling 1.8 MBq (49 μCi), about 10 ng. One gram of 210Po could thus in theory poison 20 million people, of whom 10 million would die. The actual toxicity of 210Po is lower than these estimates because radiation exposure that is spread out over several weeks (the biological half-life of polonium in humans is 30 to 50 days[84]) is somewhat less damaging than an instantaneous dose. It has been estimated that a median lethal dose of 210Po is 15 megabecquerels (0.41 mCi), or 0.089 micrograms (μg), still an extremely small amount.[85][86] For comparison, one grain of table salt is about 0.06 mg = 60 μg.[87]

Long term (chronic) effects[edit]

In addition to the acute effects, radiation exposure (both internal and external) carries a long-term risk of death from cancer of 5–10% per Sv.[82] The general population is exposed to small amounts of polonium as a radon daughter in indoor air; the isotopes 214Po and 218Po are thought to cause the majority[88] of the estimated 15,000–22,000 lung cancer deaths in the US every year that have been attributed to indoor radon.[89] Tobacco smoking causes additional exposure to polonium.[90]

Regulatory exposure limits and handling[edit]

The maximum allowable body burden for ingested 210Po is only 1.1 kBq (30 nCi), which is equivalent to a particle massing only 6.8 picograms. The maximum permissible workplace concentration of airborne 210Po is about 10 Bq/m3 (3×10−10 µCi/cm3).[91] The target organs for polonium in humans are the spleen and liver.[92] As the spleen (150 g) and the liver (1.3 to 3 kg) are much smaller than the rest of the body, if the polonium is concentrated in these vital organs, it is a greater threat to life than the dose which would be suffered (on average) by the whole body if it were spread evenly throughout the body, in the same way as caesium or tritium (as T2O).[citation needed]

210Po is widely used in industry, and readily available with little regulation or restriction.[citation needed][93] In the US, a tracking system run by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission was implemented in 2007 to register purchases of more than 16 curies (590 GBq) of polonium-210 (enough to make up 5,000 lethal doses). The IAEA «is said to be considering tighter regulations … There is talk that it might tighten the polonium reporting requirement by a factor of 10, to 1.6 curies (59 GBq).»[94] As of 2013, this is still the only alpha emitting byproduct material available, as a NRC Exempt Quantity, which may be held without a radioactive material license.[citation needed]

Polonium and its compounds must be handled in a glove box, which is further enclosed in another box, maintained at a slightly higher pressure than the glove box to prevent the radioactive materials from leaking out. Gloves made of natural rubber do not provide sufficient protection against the radiation from polonium; surgical gloves are necessary. Neoprene gloves shield radiation from polonium better than natural rubber.[95]

Cases of poisoning[edit]

Despite the element’s highly hazardous properties, circumstances in which polonium poisoning can occur are rare. Its extreme scarcity in nature, the short half-lives of all its isotopes, the specialised facilities and equipment needed to obtain any significant quantity, and safety precautions against laboratory accidents all make harmful exposure events unlikely. As such, only a handful of cases of radiation poisoning specifically attributable to polonium exposure have been confirmed.[citation needed]

20th century[edit]

In response to concerns about the risks of occupational polonium exposure, quantities of 210Po were administered to five human volunteers at the University of Rochester from 1944 to 1947, in order to study its biological behaviour. These studies were funded by the Manhattan Project and the AEC. Four men and a woman participated, all suffering from terminal cancers, and ranged in age from their early thirties to early forties; all were chosen because experimenters wanted subjects who had not been exposed to polonium either through work or accident.[96] 210Po was injected into four hospitalised patients, and orally given to a fifth. None of the administered doses (all ranging from 0.17 to 0.30 μCi kg−1) approached fatal quantities.[97][96]

The first documented death directly resulting from polonium poisoning occurred in the Soviet Union, on 10 July 1954.[98][99] An unidentified 41-year-old man presented for medical treatment on 29 June, with severe vomiting and fever; the previous day, he had been working for five hours in an area in which, unknown to him, a capsule containing 210Po had depressurised and begun to disperse in aerosol form. Over this period, his total intake of airborne 210Po was estimated at 0.11 GBq (almost 25 times the estimated LD50 by inhalation of 4.5 MBq). Despite treatment, his condition continued to worsen and he died 13 days after the exposure event.[98]

It has also been suggested that Irène Joliot-Curie’s 1956 death from leukaemia was owed to the radiation effects of polonium. She was accidentally exposed in 1946 when a sealed capsule of the element exploded on her laboratory bench.[100]

As well, several deaths in Israel during 1957–1969 have been alleged to have resulted from 210Po exposure.[101] A leak was discovered at a Weizmann Institute laboratory in 1957. Traces of 210Po were found on the hands of Professor Dror Sadeh, a physicist who researched radioactive materials. Medical tests indicated no harm, but the tests did not include bone marrow. Sadeh, one of his students, and two colleagues died from various cancers over the subsequent few years. The issue was investigated secretly, but there was never any formal admission of a connection between the leak and the deaths.[102]

21st century[edit]

The cause of the 2006 death of Alexander Litvinenko, a former Russian FSB agent who had defected to the United Kingdom in 2001, was identified to be poisoning with a lethal dose of 210Po;[103][104] it was subsequently determined that the 210Po had probably been deliberately administered to him by two Russian ex-security agents, Andrey Lugovoy and Dmitry Kovtun.[105][106] As such, Litvinenko’s death was the first (and, to date, only) confirmed instance in which polonium’s extreme toxicity has been used with malicious intent.[107][108][109]

In 2011, an allegation surfaced that the death of Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat, who died on 11 November 2004 of uncertain causes, also resulted from deliberate polonium poisoning,[110][111] and in July 2012, abnormally high concentrations of 210Po were detected in Arafat’s clothes and personal belongings by the Institut de Radiophysique in Lausanne, Switzerland.[112][113] However, the Institut’s spokesman stressed that despite these tests, Arafat’s medical reports were not consistent with 210Po poisoning,[113] and science journalist Deborah Blum suggested that tobacco smoke might rather have been responsible, as both Arafat and many of his colleagues were heavy smokers;[114] subsequent tests by both French and Russian teams determined that the elevated 210Po levels were not the result of deliberate poisoning, and did not cause Arafat’s death.[115][116]

There is also a suspicion of poisoning Roman Tsepov with polonium. He had symptoms similar to Aleksander Litvinenko.[117]

Treatment[edit]

It has been suggested that chelation agents, such as British Anti-Lewisite (dimercaprol), can be used to decontaminate humans.[118] In one experiment, rats were given a fatal dose of 1.45 MBq/kg (8.7 ng/kg) of 210Po;

all untreated rats were dead after 44 days, but 90% of the rats treated with the chelation agent

HOEtTTC remained alive for 5 months.[119]

Detection in biological specimens[edit]

Polonium-210 may be quantified in biological specimens by alpha particle spectrometry to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized patients or to provide evidence in a medicolegal death investigation. The baseline urinary excretion of polonium-210 in healthy persons due to routine exposure to environmental sources is normally in a range of 5–15 mBq/day. Levels in excess of 30 mBq/day are suggestive of excessive exposure to the radionuclide.[120]

Occurrence in humans and the biosphere[edit]

Polonium-210 is widespread in the biosphere, including in human tissues, because of its position in the uranium-238 decay chain. Natural uranium-238 in the Earth’s crust decays through a series of solid radioactive intermediates including radium-226 to the radioactive noble gas radon-222, some of which, during its 3.8-day half-life, diffuses into the atmosphere. There it decays through several more steps to polonium-210, much of which, during its 138-day half-life, is washed back down to the Earth’s surface, thus entering the biosphere, before finally decaying to stable lead-206.[121][122][123]

As early as the 1920s, French biologist Antoine Lacassagne [fr], using polonium provided by his colleague Marie Curie, showed that the element has a specific pattern of uptake in rabbit tissues, with high concentrations, particularly in liver, kidney, and testes.[124] More recent evidence suggests that this behavior results from polonium substituting for its congener sulfur, also in group 16 of the periodic table, in sulfur-containing amino-acids or related molecules[125] and that similar patterns of distribution occur in human tissues.[126] Polonium is indeed an element naturally present in all humans, contributing appreciably to natural background dose, with wide geographical and cultural variations, and particularly high levels in arctic residents, for example.[127]

Tobacco[edit]

Polonium-210 in tobacco contributes to many of the cases of lung cancer worldwide. Most of this polonium is derived from lead-210 deposited on tobacco leaves from the atmosphere; the lead-210 is a product of radon-222 gas, much of which appears to originate from the decay of radium-226 from fertilizers applied to the tobacco soils.[52][128][129][130][131]

The presence of polonium in tobacco smoke has been known since the early 1960s.[132][133] Some of the world’s biggest tobacco firms researched ways to remove the substance—to no avail—over a 40-year period. The results were never published.[52]

Food[edit]

Polonium is found in the food chain, especially in seafood.[134][135]

See also[edit]

- Polonium halo

- Poisoning of Alexander Litvinenko

References[edit]

- ^ a b Thayer, John S. (2010). «Relativistic Effects and the Chemistry of the Heavier Main Group Elements». Relativistic Methods for Chemists. Challenges and Advances in Computational Chemistry and Physics. 10: 78. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9975-5_2. ISBN 978-1-4020-9974-8.

- ^ Boutin, Chad. «Polonium’s Most Stable Isotope Gets Revised Half-Life Measurement». nist.gov. NIST Tech Beat. Retrieved 9 September 2014.

- ^ a b c «Polonium» (PDF). Argonne National Laboratory. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Greenwood, p. 250

- ^ «210PO α decay». Nuclear Data Center, Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute. 2000. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Greenwood, p. 753

- ^ Miessler, Gary L.; Tarr, Donald A. (2004). Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-13-120198-9.

- ^ «The beta Po (A_i) Structure». Naval Research Laboratory. 20 November 2000. Archived from the original on 4 February 2001. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Desando, R. J.; Lange, R. C. (1966). «The structures of polonium and its compounds—I α and β polonium metal». Journal of Inorganic and Nuclear Chemistry. 28 (9): 1837–1846. doi:10.1016/0022-1902(66)80270-1.

- ^ Beamer, W. H.; Maxwell, C. R. (1946). «The Crystal Structure of Polonium». Journal of Chemical Physics. 14 (9): 569. doi:10.1063/1.1724201. hdl:2027/mdp.39015086430371.

- ^ Rollier, M. A.; Hendricks, S. B.; Maxwell, L. R. (1936). «The Crystal Structure of Polonium by Electron Diffraction». Journal of Chemical Physics. 4 (10): 648. Bibcode:1936JChPh…4..648R. doi:10.1063/1.1749762.

- ^ Wąs, Bogdan; Misiak, Ryszard; Bartyzel, Mirosław; Petelenz, Barbara (2006). «Thermochromatographic separation of 206,208Po from a bismuth target bombarded with protons» (PDF). Nukleonika. 51 (Suppl. 2): s3–s5.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Condit, Ralph H.; Gray, Leonard W.; Mitchell, Mark A. (2014). Pseudo-evaporation of high specific activity alpha-emitting materials. EFCOG 2014 Safety Analysis Workshop. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

- ^ a b c d e f Emsley, John (2001). Nature’s Building Blocks. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 330–332. ISBN 978-0-19-850341-5.

- ^ Bagnall, p. 206

- ^ Keller, Cornelius; Wolf, Walter; Shani, Jashovam. «Radionuclides, 2. Radioactive Elements and Artificial Radionuclides». Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.o22_o15.

- ^ Bagnall, p. 199

- ^ a b Greenwood, p. 766

- ^ Weigel, F. (1959). «Chemie des Poloniums». Angewandte Chemie. 71 (9): 289–316. Bibcode:1959AngCh..71..289W. doi:10.1002/ange.19590710902.

- ^ Holleman, A. F.; Wiberg, E. (2001). Inorganic Chemistry. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-352651-9.

- ^ a b Figgins, P. E. (1961) The Radiochemistry of Polonium, National Academy of Sciences, US Atomic Energy Commission, pp. 13–14 Google Books

- ^ a b Greenwood, pp. 765, 771, 775

- ^ Bagnall, pp. 212–226

- ^ a b Zingaro, Ralph A. (2011). «Polonium: Organometallic Chemistry». Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–3. doi:10.1002/9781119951438.eibc0182. ISBN 9781119951438.

- ^ Murin, A. N.; Nefedov, V. D.; Zaitsev, V. M.; Grachev, S. A. (1960). «Production of organopolonium compounds by using chemical alterations taking place during the β-decay of RaE» (PDF). Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR (in Russian). 133 (1): 123–125. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Wiberg, Egon; Holleman, A. F. and Wiberg, Nils Inorganic Chemistry, Academic Press, 2001, p. 594, ISBN 0-12-352651-5.

- ^ Bagnall, K. W.; d’Eye, R. W. M. (1954). «The Preparation of Polonium Metal and Polonium Dioxide». J. Chem. Soc.: 4295–4299. doi:10.1039/JR9540004295.

- ^ a b Bagnall, K. W.; d’Eye, R. W. M.; Freeman, J. H. (1955). «The polonium halides. Part I. Polonium chlorides». Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 2320. doi:10.1039/JR9550002320.

- ^ a b Bagnall, K. W.; d’Eye, R. W. M.; Freeman, J. H. (1955). «The polonium halides. Part II. Bromides». Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 3959. doi:10.1039/JR9550003959.

- ^ Bagnall, K. W.; d’Eye, R. W. M.; Freeman, J. H. (1956). «657. The polonium halides. Part III. Polonium tetraiodide». Journal of the Chemical Society (Resumed): 3385. doi:10.1039/JR9560003385.

- ^ Collé, R.; Fitzgerald, R.P.; Laureano-Perez, L. (13 August 2014). «A new determination of the 209Po half-life». Journal of Physics G. 41 (10): 105103. Bibcode:2014JPhG…41j5103C. doi:10.1088/0954-3899/41/10/105103.

- ^ Emsley, John (2011). Nature’s Building Blocks: An A-Z Guide to the Elements (New ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. p. 415. ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- ^ a b Curie, P.; Curie, M. (1898). «Sur une substance nouvelle radio-active, contenue dans la pechblende» [On a new radioactive substance contained in pitchblende] (PDF). Comptes Rendus (in French). 127: 175–178. Archived from the original on 23 July 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) English translation. - ^ Krogt, Peter van der. «84. Polonium — Elementymology & Elements Multidict». elements.vanderkrogt.net. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- ^ Pfützner, M. (1999). «Borders of the Nuclear World – 100 Years After Discovery of Polonium». Acta Physica Polonica B. 30 (5): 1197. Bibcode:1999AcPPB..30.1197P.

- ^ Adloff, J. P. (2003). «The centennial of the 1903 Nobel Prize for physics». Radiochimica Acta. 91 (12–2003): 681–688. doi:10.1524/ract.91.12.681.23428. S2CID 120150862.

- ^ a b Kabzinska, K. (1998). «Chemical and Polish aspects of polonium and radium discovery». Przemysł Chemiczny. 77 (3): 104–107.

- ^ Curie, P.; Curie, M.; Bémont, G. (1898). «Sur une nouvelle substance fortement radio-active contenue dans la pechblende» [On a new, strongly radioactive substance contained in pitchblende] (PDF). Comptes Rendus (in French). 127: 1215–1217. Archived from the original on 22 July 2013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) English translation Archived 6 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine - ^ «Polonium and Radio-Tellurium». Nature. 73 (549): 549. 1906. Bibcode:1906Natur..73R.549.. doi:10.1038/073549b0.

- ^ Neufeldt, Sieghard (2012). Chronologie Chemie: Entdecker und Entdeckungen. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9783527662845.

- ^ a b Nuclear Weapons FAQ, Section 4.1, Version 2.04: 20 February 1999. Nuclearweaponarchive.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-28.

- ^ RESTRICTED DATA DECLASSIFICATION DECISIONS, 1946 TO THE PRESENT (RDD-7), January 1, 2001, U.S. Department of Energy Office of Declassification, via fas.org

- ^ American nuclear guinea pigs: three decades of radiation experiments on U.S. citizens Archived 2013-07-30 at the Wayback Machine. United States. Congress. House. of the Committee on Energy and Commerce. Subcommittee on Energy Conservation and Power, published by U.S. Government Printing Office, 1986, Identifier Y 4.En 2/3:99-NN, Electronic Publication Date 2010, at the University of Nevada, Reno, unr.edu

- ^ «Studies of polonium metabolism in human subjects», Chapter 3 in Biological Studies with Polonium, Radium, and Plutonium, National, Nuclear Energy Series, Volume VI-3, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1950, cited in «American Nuclear Guinea Pigs …», 1986 House Energy and Commerce committee report

- ^ Moss, William and Eckhardt, Roger (1995) «The Human Plutonium Injection Experiments», Los Alamos Science, Number 23.

- ^ Carvalho, F.; Fernandes, S.; Fesenko, S.; Holm, E.; Howard, B.; Martin, P.; Phaneuf, P.; Porcelli, D.; Pröhl, G.; Twining, J. (2017). The Environmental Behaviour of Polonium. Technical Reports Series — International Atomic Energy Agency. Technical reports series. Vol. 484. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency. p. 1. ISBN 978-92-0-112116-5. ISSN 0074-1914.

- ^ Greenwood, p. 746

- ^ Bagnall, p. 198

- ^ Kilthau, Gustave F. (1996). «Cancer risk in relation to radioactivity in tobacco». Radiologic Technology. 67 (3): 217–222. PMID 8850254.

- ^ «Alpha Radioactivity (210 Polonium) and Tobacco Smoke». Archived from the original on 9 June 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ a b c Monique, E. Muggli; Ebbert, Jon O.; Robertson, Channing; Hurt, Richard D. (2008). «Waking a Sleeping Giant: The Tobacco Industry’s Response to the Polonium-210 Issue». American Journal of Public Health. 98 (9): 1643–50. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.130963. PMC 2509609. PMID 18633078.

- ^ Adloff, J. P. & MacCordick, H. J. (1995). «The Dawn of Radiochemistry». Radiochimica Acta. 70/71: 13–22. doi:10.1524/ract.1995.7071.special-issue.13. S2CID 99790464., reprinted in Adloff, J. P. (1996). One hundred years after the discovery of radioactivity. p. 17. ISBN 978-3-486-64252-0.

- ^ a b Greenwood, p. 249

- ^ Schulz, Wallace W.; Schiefelbein, Gary F.; Bruns, Lester E. (1969). «Pyrochemical Extraction of Polonium from Irradiated Bismuth Metal». Ind. Eng. Chem. Process Des. Dev. 8 (4): 508–515. doi:10.1021/i260032a013.

- ^ «Q&A: Polonium-210». RSC Chemistry World. 27 November 2006. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ «Most Polonium Made Near the Volga River». The Moscow Times – News. 11 January 2007.

- ^ Usanov, V. I.; Pankratov, D. V.; Popov, É. P.; Markelov, P. I.; Ryabaya, L. D.; Zabrodskaya, S. V. (1999). «Long-lived radionuclides of sodium, lead-bismuth, and lead coolants in fast-neutron reactors». Atomic Energy. 87 (3): 658–662. doi:10.1007/BF02673579. S2CID 94738113.

- ^ Naumov, V. V. (November 2006). За какими корабельными реакторами будущее?. Атомная стратегия (in Russian). 26.

- ^ Atterling, H.; Forsling, W. (1959). «Light Polonium Isotopes from Carbon Ion Bombardments of Platinum». Arkiv för Fysik. 15 (1): 81–88. OSTI 4238755.

- ^ a b «Радиоизотопные источники тепла». Archived from the original on 1 May 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2016. (in Russian). npc.sarov.ru

- ^ Bagnall, p. 225

- ^ a b Greenwood, p. 251

- ^ Hanslmeier, Arnold (2002). The sun and space weather. Springer. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-4020-0684-5.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew (1987). Solar System Log. London: Jane’s Publishing Company Ltd. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-7106-0444-6.

- ^ Ritter, Sebastian (2021). «Comparative Study of Gamma to Neutron Ratios of various (alpha, neutron) Neutron Sources». arXiv:2111.02774 [nucl-ex].

- ^ Rhodes, Richard (2002). Dark Sun: The Making of the Hydrogen Bomb. New York: Walker & Company. pp. 187–188. ISBN 978-0-684-80400-2.

- ^ Красивая версия «самоубийства» Литвиненко вследствие криворукости (in Russian). stringer.ru (2006-11-26).

- ^ Boice, John D.; Cohen, Sarah S.; et al. (2014). «Mortality Among Mound Workers Exposed to Polonium-210 and Other Sources of Radiation, 1944–1979». Radiation Research. 181 (2): 208–28. Bibcode:2014RadR..181..208B. doi:10.1667/RR13395.1. ISSN 0033-7587. OSTI 1286690. PMID 24527690. S2CID 7350371.

- ^ «Static Control for Electronic Balance Systems» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ «BBC News : College breaches radioactive regulations». 12 March 2002. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ «Staticmaster Ionizing Brushes». AMSTAT Industries. Archived from the original on 26 September 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ «General domestic licenses for byproduct material». Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ «Radioactive spark plugs». Oak Ridge Associated Universities. 20 January 1999. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ Pittman, Cassandra (3 February 2017). «Polonium». The Instrumentation Center. University of Toledo. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ «Safety data for hydrogen cyanide». Physical & Theoretical Chemistry Lab, Oxford University. Archived from the original on 11 February 2002.

- ^ Bagnall, pp. 202–6

- ^ «Polonium-210: Effects, symptoms, and diagnosis». Medical News Today. 28 July 2017.

- ^ Momoshima, N.; Song, L. X.; Osaki, S.; Maeda, Y. (2001). «Formation and emission of volatile polonium compound by microbial activity and polonium methylation with methylcobalamin». Environ Sci Technol. 35 (15): 2956–2960. Bibcode:2001EnST…35.2956M. doi:10.1021/es001730. PMID 11478248.

- ^

Momoshima, N.; Song, L. X.; Osaki, S.; Maeda, Y. (2002). «Biologically induced Po emission from fresh water». J Environ Radioact. 63 (2): 187–197. doi:10.1016/S0265-931X(02)00028-0. PMID 12363270. - ^ Li, Chunsheng; Sadi, Baki; Wyatt, Heather; Bugden, Michelle; et al. (2010). «Metabolism of 210Po in rats: volatile 210Po in excreta». Radiation Protection Dosimetry. 140 (2): 158–162. doi:10.1093/rpd/ncq047. PMID 20159915.

- ^ a b «Health Impacts from Acute Radiation Exposure» (PDF). Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ «Nuclide Safety Data Sheet: Polonium–210» (PDF). hpschapters.org. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Naimark, D.H. (4 January 1949). «Effective half-life of polonium in the human». Technical Report MLM-272/XAB, Mound Lab., Miamisburg, OH. OSTI 7162390.

- ^ Carey Sublette (14 December 2006). «Polonium Poisoning». Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Harrison, J.; Leggett, Rich; Lloyd, David; Phipps, Alan; et al. (2007). «Polonium-210 as a poison». J. Radiol. Prot. 27 (1): 17–40. Bibcode:2007JRP….27…17H. doi:10.1088/0952-4746/27/1/001. PMID 17341802. S2CID 27764788.

The conclusion is reached that 0.1–0.3 GBq or more absorbed to blood of an adult male is likely to be fatal within 1 month. This corresponds to ingestion of 1–3 GBq or more, assuming 10% absorption to blood

- ^ Yasar Safkan. «Approximately how many atoms are in a grain of salt?». PhysLink.com: Physics & Astronomy.

- ^ Health Risks of Radon and Other Internally Deposited Alpha-Emitters: BEIR IV. National Academy Press. 1988. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-309-03789-1.

- ^ Health Effects Of Exposure To Indoor Radon. Washington: National Academy Press. 1999. Archived from the original on 19 September 2006.

- ^ «The Straight Dope: Does smoking organically grown tobacco lower the chance of lung cancer?». 28 September 2007. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ «Nuclear Regulatory Commission limits for 210Po». U.S. NRC. 12 December 2008. Retrieved 12 January 2009.

- ^ «PilgrimWatch – Pilgrim Nuclear – Health Impact». Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Bastian, R.K.; Bachmaier, J.T.; Schmidt, D.W.; Salomon, S.N.; Jones, A.; Chiu, W.A.; Setlow, L.W.; Wolbarst, A.W.; Yu, C. (1 January 2004). «Radioactive Materials in Biosolids: National Survey, Dose Modeling & POTW Guidance». Proceedings of the Water Environment Federation. 2004 (1): 777–803. doi:10.2175/193864704784343063. ISSN 1938-6478.

- ^ Zimmerman, Peter D. (19 December 2006). «The Smoky Bomb Threat». The New York Times. Retrieved 19 December 2006.

- ^ Bagnall, p. 204

- ^ a b Moss, William; Eckhardt, Roger (1995). «The human plutonium injection experiments» (PDF). Los Alamos Science. 23: 177–233.

- ^ Fink, Robert (1950). Biological studies with polonium, radium, and plutonium. National Nuclear Energy Series (in Russian). Vol. VI-3. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 5-86656-114-X.

- ^ a b Gasteva, G. N. (2001). «Ostraja lučevaja boleznʹ ot postuplenija v organizm polonija» [Acute radiation sickness by ingestion of polonium into the body]. In Ilʹin, L. A. (ed.). Radiacionnaja medicina: rukovodstvo dlja vračej-issledovatelej i organizatorov zdravooxranenija, Tom 2 (Radiacionnye poraženija čeloveka) [Radiation medicine: a guide for medical researchers and healthcare managers, Volume 2 (Radiation damage to humans)] (in Russian). IzdAT. pp. 99–107. ISBN 5-86656-114-X.

- ^ Harrison, John; Leggett, Rich; Lloyd, David; Phipps, Alan; Scott, Bobby (2 March 2007). «Polonium-210 as a poison». Journal of Radiological Protection. 27 (1): 17–40. Bibcode:2007JRP….27…17H. doi:10.1088/0952-4746/27/1/001. PMID 17341802. S2CID 27764788.

- ^ Manier, Jeremy (4 December 2006). «Innocent chemical a killer». The Daily Telegraph (Australia). Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ Karpin, Michael (2006). The bomb in the basement: How Israel went nuclear and what that means for the world. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-6594-2.

- ^ Maugh, Thomas; Karen Kaplan (1 January 2007). «A restless killer radiates intrigue». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 17 September 2008.

- ^ Geoghegan, Tom (24 November 2006). «The mystery of Litvinenko’s death». BBC News.

- ^ «UK requests Lugovoi extradition». BBC News. 28 May 2007. Retrieved 5 May 2009.

- ^ «Report». The Litvinenko Inquiry. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Addley, Esther; Harding, Luke (21 January 2016). «Litvinenko ‘probably murdered on personal orders of Putin’«. The Guardian. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ Boggan, Steve (5 June 2007). «Who else was poisoned by polonium?». The Guardian. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Poort, David (6 November 2013). «Polonium: a silent killer». Al Jazeera News. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Froidevaux, Pascal; Bochud, François; Baechler, Sébastien; Castella, Vincent; Augsburger, Marc; Bailat, Claude; Michaud, Katarzyna; Straub, Marietta; Pecchia, Marco; Jenk, Theo M.; Uldin, Tanya; Mangin, Patrice (February 2016). «²¹⁰Po poisoning as possible cause of death: forensic investigations and toxicological analysis of the remains of Yasser Arafat». Forensic Science International. 259: 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2015.09.019. PMID 26707208. S2CID 207751390. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ^ «الأخبار — ضابط فلسطيني: خصوم عرفات قتلوه عربي». Al Jazeera. 17 January 2011. Archived from the original on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- ^ «George Galloway and Alex Goldfarb on Litvinenko inquiry». Newsnight. 21 January 2016. Event occurs at 1:53. BBC. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- ^ Froidevaux, P.; Baechler, S. B.; Bailat, C. J.; Castella, V.; Augsburger, M.; Michaud, K.; Mangin, P.; Bochud, F. O. O. (2013). «Improving forensic investigation for polonium poisoning». The Lancet. 382 (9900): 1308. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61834-6. PMID 24120205. S2CID 32134286.

- ^ a b Bart, Katharina (2012-07-03). Swiss institute finds polonium in Arafat’s effects Archived 2015-10-07 at the Wayback Machine. Reuters.

- ^ «Yasser Arafat and the radioactive cigarette». Wired.com. 12 June 2012. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ Isachenkov, Vadim (2013-12-27) Russia: Arafat’s death not caused by radiation. Associated Press.

- ^ «Arafat did not die of poisoning, French tests conclude». Reuters. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ «The Putin bodyguard riddle». The Sunday Times. 3 December 2006.

- ^ «Guidance for Industry. Internal Radioactive Contamination — Development of Decorporation Agents» (PDF). US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- ^ Rencováa J.; Svoboda V.; Holuša R.; Volf V.; et al. (1997). «Reduction of subacute lethal radiotoxicity of polonium-210 in rats by chelating agents». International Journal of Radiation Biology. 72 (3): 341–8. doi:10.1080/095530097143338. PMID 9298114.

- ^ Baselt, R. Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man Archived 2013-06-16 at the Wayback Machine, 10th edition, Biomedical Publications, Seal Beach, CA.

- ^ Hill, C. R. (1960). «Lead-210 and Polonium-210 in Grass». Nature. 187 (4733): 211–212. Bibcode:1960Natur.187..211H. doi:10.1038/187211a0. PMID 13852349. S2CID 4261294.

- ^ Hill, C. R. (1963). «Natural occurrence of unsupported radium-F (Po-210) in tissue». Health Physics. 9: 952–953. PMID 14061910.

- ^ Heyraud, M.; Cherry, R. D. (1979). «Polonium-210 and lead-210 in marine food chains». Marine Biology. 52 (3): 227–236. doi:10.1007/BF00398136. S2CID 58921750.

- ^ Lacassagne, A. & Lattes, J. (1924) Bulletin d’Histologie Appliquée à la Physiologie et à la Pathologie, 1, 279.

- ^ Vasken Aposhian, H.; Bruce, D. C. (1991). «Binding of Polonium-210 to Liver Metallothionein». Radiation Research. 126 (3): 379–382. Bibcode:1991RadR..126..379A. doi:10.2307/3577929. JSTOR 3577929. PMID 2034794.

- ^ Hill, C. R. (1965). «Polonium-210 in man». Nature. 208 (5009): 423–8. Bibcode:1965Natur.208..423H. doi:10.1038/208423a0. PMID 5867584. S2CID 4215661.

- ^ Hill, C. R. (1966). «Polonium-210 Content of Human Tissues in Relation to Dietary Habit». Science. 152 (3726): 1261–2. Bibcode:1966Sci…152.1261H. doi:10.1126/science.152.3726.1261. PMID 5949242. S2CID 33510717.

- ^ Martell, E. A. (1974). «Radioactivity of tobacco trichomes and insoluble cigarette smoke particles». Nature. 249 (5454): 214–217. Bibcode:1974Natur.249..215M. doi:10.1038/249215a0. PMID 4833238. S2CID 4281866. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ Martell, E. A. (1975). «Tobacco Radioactivity and Cancer in Smokers: Alpha interactions with chromosomes of cells surrounding insoluble radioactive smoke particles may cause cancer and contribute to early atherosclerosis development in cigarette smokers». American Scientist. 63 (4): 404–412. Bibcode:1975AmSci..63..404M. JSTOR 27845575. PMID 1137236.

- ^ Tidd, M. J. (2008). «The big idea: polonium, radon and cigarettes». Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 101 (3): 156–7. doi:10.1258/jrsm.2007.070021. PMC 2270238. PMID 18344474.

- ^ Birnbauer, William (2008-09-07) «Big Tobacco covered up radiation danger». The Age, Melbourne, Australia

- ^ Radford EP Jr; Hunt VR (1964). «Polonium 210: a volatile radioelement in cigarettes». Science. 143 (3603): 247–9. Bibcode:1964Sci…143..247R. doi:10.1126/science.143.3603.247. PMID 14078362. S2CID 23455633.

- ^ Kelley TF (1965). «Polonium 210 content of mainstream cigarette smoke». Science. 149 (3683): 537–538. Bibcode:1965Sci…149..537K. doi:10.1126/science.149.3683.537. PMID 14325152. S2CID 22567612.

- ^ Ota, Tomoko; Sanada, Tetsuya; Kashiwara, Yoko; Morimoto, Takao; et al. (2009). «Evaluation for Committed Effective Dose Due to Dietary Foods by the Intake for Japanese Adults». Japanese Journal of Health Physics. 44: 80–88. doi:10.5453/jhps.44.80.

- ^ Smith-Briggs, JL; Bradley, EJ (1984). «Measurement of natural radionuclides in U.K. diet». Science of the Total Environment. 35 (3): 431–40. Bibcode:1984ScTEn..35..431S. doi:10.1016/0048-9697(84)90015-9. PMID 6729447.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bagnall, K. W. (1962). «The Chemistry of Polonium». Advances in Inorganic Chemistry and Radiochemistry. Vol. 4. New York: Academic Press. pp. 197–226. doi:10.1016/S0065-2792(08)60268-X. ISBN 978-0-12-023604-6. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth–Heinemann. ISBN 978-0080379418.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polonium.

Look up Polonium in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- Polonium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polonium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | (pə-LOH-nee-əm) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allotropes | α, β | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass number | [209] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Polonium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 84 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 16 (chalcogens) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6s2 6p4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 527 K (254 °C, 489 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1235 K (962 °C, 1764 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | α-Po: 9.196 g/cm3 β-Po: 9.398 g/cm3 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | ca. 13 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 102.91 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.4 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, +2, +4, +5,[1] +6 (an amphoteric oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 168 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 140±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 197 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of polonium |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | from decay | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | cubic

α-Po |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||