Coordinates: 52°15′N 18°50′E / 52.250°N 18.833°E

|

Republic of Poland Polish People’s Republic (1952–1989) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947–1989 | ||||||||

|

Flag Coat of arms |

||||||||

| Anthem: Mazurek Dąbrowskiego «Poland Is Not Yet Lost» |

||||||||

The Polish People’s Republic in 1989 |

||||||||

| Status | Warsaw Pact and Comecon member | |||||||

| Capital

and largest city |

Warsaw 52°13′N 21°02′E / 52.217°N 21.033°E |

|||||||

| Official languages | Polish | |||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (de facto) State atheism (de jure) |

|||||||

| Demonym(s) | Polish, Pole | |||||||

| Government | 1947–1956: Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic under a Stalinist dictatorship 1956–1989: Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic 1981–1983: military junta |

|||||||

| First Secretary and Leader | ||||||||

|

• 1947–1956 (first) |

Bolesław Bierut | |||||||

|

• 1989–1990 (last) |

Mieczysław Rakowski | |||||||

| Head of Council | ||||||||

|

• 1947–1952 (first) |

Bolesław Bierut | |||||||

|

• 1985–1989 (last) |

Wojciech Jaruzelski | |||||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||||

|

• 1944–1947 (first) |

E. Osóbka-Morawski | |||||||

|

• 1989 (last) |

Tadeusz Mazowiecki | |||||||

| Legislature | Sejm | |||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | |||||||

|

• Small Constitution |

19 February 1947 | |||||||

|

• July Constitution |

22 July 1952 | |||||||

|

• Polish October |

21 October 1956 | |||||||

|

• Martial law |

13 December 1981 | |||||||

|

• Free elections |

4 June 1989 | |||||||

|

• Dissolution |

31 December 1989 | |||||||

| Area | ||||||||

|

• Total |

312,685 km2 (120,728 sq mi) | |||||||

| Population | ||||||||

|

• 1989 estimate |

37,970,155 | |||||||

| HDI (1989) | 0.910[1] very high · 33rd |

|||||||

| Currency | Złoty (PLZ) | |||||||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | |||||||

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+2 (CEST) | |||||||

| Driving side | right | |||||||

| Calling code | +48 | |||||||

| ISO 3166 code | PL | |||||||

|

The Polish People’s Republic (Polish: Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million near the end of its existence, it was the second most-populous communist and Eastern Bloc country in Europe.[2] Having a unitary Marxist–Leninist government, it was also one of the main signatories of the Warsaw Pact alliance. The largest city and official capital since 1947 was Warsaw, followed by the industrial city of Łódź and cultural city of Kraków. The country was bordered by the Baltic Sea to the north, the Soviet Union to the east, Czechoslovakia to the south, and East Germany to the west.

Between 1952 and 1989 Poland was ruled by a communist government established after the Red Army’s takeover of Polish territory from German occupation in World War II. The state’s official name was the «Republic of Poland» (Rzeczpospolita Polska) between 1947 and 1952 in accordance with the temporary Small Constitution of 1947.[3] The name «People’s Republic» was introduced and defined by the Constitution of 1952. Like other Eastern Bloc countries (East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Albania),[a] Poland was regarded as a satellite state in the Soviet sphere of interest, but it was never a part of the Soviet Union.[3][4][5]

The Polish United Workers’ Party became the dominant political faction in the Polish People’s Republic, officially making it a socialist country. During this period Poland was a de facto one-party state but it had more liberal policies than other states in the Eastern Bloc and it was characterized by constant internal struggles for democracy. Throughout its existence, economic hardships and social unrest were common in almost every decade. The nation was split between those who supported the party, those who were opposed to it and those who refused to engage in political activity. Despite this, some groundbreaking achievements were established during the People’s Republic such as improved living conditions, rapid industrialization, urbanization, and access to universal health care and education was made available. The birth rate was high and the population almost doubled between 1947 and 1989. The party’s most successful accomplishment was the rebuilding of ruined Warsaw after World War II and the complete eradication of illiteracy.[6][7]

The Polish People’s Army was the main branch of the Armed Forces, though Soviet Army units were also stationed in Poland as in all other Warsaw Pact countries.[4] The UB and succeeding SB were the chief intelligence agencies that acted as secret police, similar to the East German Stasi and Soviet KGB. The official police organization, which was also responsible for supposed peacekeeping and violent suppression of protests, was renamed Citizens’ Militia (MO). The Militia’s elite ZOMO squads committed various serious crimes to maintain the communists in power, including the harsh treatment of protesters, arrest of opposition leaders and in extreme cases, murder,[8] with at least 22,000 people killed by the regime during its rule.[9] As a result, Poland had a high imprisonment rate but one of the lowest crime rates in the world.[10]

History[edit]

1945–1956[edit]

In the summer of 1944 the Polish Committee of National Liberation was established by Soviet-backed Polish communists to control territory retaken from Nazi Germany. On 1 January 1945 the committee was replaced by the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland, all the key posts of which were held by members of the communist Polish Workers’ Party.

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Stalin was able to present his western allies, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, with a fait accompli in Poland. His armed forces were in occupation of the country, and the communists were in control of its administration. The Soviet Union was in the process of reincorporating the lands to the east of the Curzon Line, which it had invaded and occupied between 1939 and 1941.

In compensation, Poland was granted German-populated territories in Pomerania, Silesia, and Brandenburg east of the Oder–Neisse line, including the southern half of East Prussia. As a result of these actions, Poland lost 77,035 km2 (29,743 sq mi) of land compared to its pre-WWII territory. These were confirmed, pending a final peace conference with Germany,[11] at the Tripartite Conference of Berlin, otherwise known as the Potsdam Conference in August 1945 after the end of the war in Europe. The Potsdam Agreement also sanctioned the transfer of German population out of the acquired territories. Stalin was determined that Poland’s new communist government would become his tool towards making Poland a satellite state like other countries in Central and Eastern Europe. He had severed relations with the Polish government-in-exile in London in 1943, but to appease Roosevelt and Churchill he agreed at Yalta that a coalition government would be formed. The Provisional Government of National Unity was established in June 1946 with the communists holding a majority of key posts, and with Soviet support they soon gained almost total control of the country.

In June 1946, the «Three Times Yes» referendum was held on a number of issues—abolition of the Senate of Poland, land reform, and making the Oder–Neisse line Poland’s western border. The communist-controlled Interior Ministry issued results showing that all three questions passed overwhelmingly. Years later, however, evidence was uncovered showing that the referendum had been tainted by large-scale fraud, and only the third question actually passed.[12] Władysław Gomułka then took advantage of a split in the Polish Socialist Party. One faction, which included Prime Minister Edward Osóbka-Morawski, wanted to join forces with the Peasant Party and form a united front against the communists. Another faction, led by Józef Cyrankiewicz, argued that the socialists should support the communists in carrying through a socialist program while opposing the imposition of one-party rule. Pre-war political hostilities continued to influence events, and Stanisław Mikołajczyk would not agree to form a united front with the socialists. The communists played on these divisions by dismissing Osóbka-Morawski and making Cyrankiewicz Prime Minister.

Between the referendum and the January 1947 general elections, the opposition was subjected to persecution. Only the candidates of the pro-government «Democratic Bloc» (the PPR, Cyrankiewicz’ faction of the PPS, and the Democratic Party) were allowed to campaign completely unmolested. Meanwhile, several opposition candidates were prevented from campaigning at all. Mikołajczyk’s Polish People’s Party (PSL) in particular suffered persecution; it had opposed the abolition of the Senate as a test of strength against the government. Although it supported the other two questions, the Communist-dominated government branded the PSL «traitors». This massive oppression was overseen by Gomułka and the provisional president, Bolesław Bierut.

Border changes of Poland after World War II. The eastern territories (Kresy) were annexed by the Soviet Union. The western territories, referred to as the «Recovered Territories», were granted as war reparations. Despite the western lands being more industrialized, Poland lost 77,035 km2 (29,743 sq mi) and major cities like Lviv and Vilnius.

The official results of the election showed the Democratic Bloc with 80.1 percent of the vote. The Democratic Bloc was awarded 394 seats to only 28 for the PSL. Mikołajczyk immediately resigned to protest this so-called ‘implausible result’ and fled to the United Kingdom in April rather than face arrest. Later, some historians[citation needed]announced that the official results were only obtained through massive fraud. Government officials didn’t even count the real votes in many areas and simply filled in the relevant documents in accordance with instructions from the communists. In other areas, the ballot boxes were either destroyed or replaced with boxes containing prefilled ballots.

The 1947 election marked the beginning of undisguised communist rule in Poland, though it was not officially transformed into the Polish People’s Republic until the adoption of the 1952 Constitution. However, Gomułka never supported Stalin’s control over the Polish communists and was soon replaced as party leader by the more pliable Bierut. In 1948, the communists consolidated their power, merging with Cyrankiewicz’ faction of the PPS to form the Polish United Workers’ Party (known in Poland as ‘the Party’), which would monopolise political power in Poland until 1989. In 1949, Polish-born Soviet Marshal Konstantin Rokossovsky became the Minister of National Defence, with the additional title Marshal of Poland, and in 1952 he became Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers (deputy premier).

A propaganda poster enhancing to vote for Communist policies in the «Three Times Yes» 1946 referendum

Over the coming years, private industry was nationalised, the land seized from the pre-war landowners and redistributed to the lower-class farmers, and millions of Poles were transferred from the lost eastern territories to the lands acquired from Germany. Poland was now to be brought into line with the Soviet model of a «people’s democracy» and a centrally planned socialist economy. The government also embarked on the collectivisation of agriculture, although the pace was slower than in other satellites: Poland remained the only Eastern Bloc country where individual farmers dominated agriculture.

Through a careful balance of agreement, compromise and resistance — and having signed an agreement of coexistence with the communist regime — cardinal primate Stefan Wyszyński maintained and even strengthened the Polish church through a series of failed government leaders. He was put under house arrest from 1953 to 1956 for failing to punish priests who participated in anti-government activity.[13][14][15]

Bierut died in March 1956, and was replaced with Edward Ochab, who held the position for seven months. In June, workers in the industrial city of Poznań went on strike, in what became known as 1956 Poznań protests. Voices began to be raised in the Party and among the intellectuals calling for wider reforms of the Stalinist system. Eventually, power shifted towards Gomułka, who replaced Ochab as party leader. Hardline Stalinists were removed from power and many Soviet officers serving in the Polish Army were dismissed. This marked the end of the Stalinist era.

1970s and 1980s[edit]

In 1970, Gomułka’s government had decided to adopt massive increases in the prices of basic goods, including food. The resulting widespread violent protests in December that same year resulted in a number of deaths. They also forced another major change in the government, as Gomułka was replaced by Edward Gierek as the new First Secretary. Gierek’s plan for recovery was centered on massive borrowing, mainly from the United States and West Germany, to re-equip and modernize Polish industry, and to import consumer goods to give the workers some incentive to work. While it boosted the Polish economy, and is still remembered as the «Golden Age» of socialist Poland, it left the country vulnerable to global economic fluctuations and western undermining, and the repercussions in the form of massive debt is still felt in Poland even today. This Golden Age came to an end after the 1973 energy crisis. The failure of the Gierek government, both economically and politically, soon led to the creation of opposition in the form of trade unions, student groups, clandestine newspapers and publishers, imported books and newspapers, and even a «flying university.»

Queues waiting to enter grocery stores in Warsaw and other Polish cities and towns were typical in the late 1980s. The availability of food and goods varied at times, and the most sought after basic item was toilet paper.

On 16 October 1978, the Archbishop of Kraków, Cardinal Karol Wojtyła, was elected Pope, taking the name John Paul II. The election of a Polish Pope had an electrifying effect on what had been, even under communist rule, one of the most devoutly Catholic nations in Europe. Gierek is alleged to have said to his cabinet, «O God, what are we going to do now?» or, as occasionally reported, «Jesus and Mary, this is the end». When John Paul II made his first papal tour of Poland in June 1979, half a million people heard him speak in Warsaw; he did not call for rebellion, but instead encouraged the creation of an «alternative Poland» of social institutions independent of the government, so that when the next economic crisis came, the nation would present a united front.

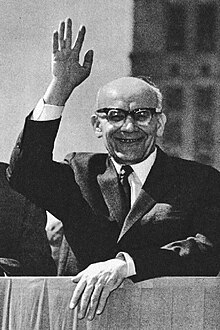

General Wojciech Jaruzelski served as the last leader of the Polish People’s Republic from 1981 till 1989

A new wave of labour strikes undermined Gierek’s government, and in September Gierek, who was in poor health, was finally removed from office and replaced as Party leader by Stanisław Kania. However, Kania was unable to find an answer for the fast-eroding support of communism in Poland. Labour turmoil led to the formation of the independent trade union Solidarity (Solidarność) in September 1980, originally led by Lech Wałęsa. In fact, Solidarity became a broad anti-communist social movement ranging from people associated with the Catholic Church, to members of the anti-Stalinist left. By the end of 1981, Solidarity had nine million members—a quarter of Poland’s population and three times as many as the PUWP had. Kania resigned under Soviet pressure in October and was succeeded by Wojciech Jaruzelski, who had been Defence minister since 1968 and Premier since February.

The new Warszawa Centralna railway station in Warsaw had automatic doors and escalators. It was a flagship project during the 1970s economic boom and was dubbed the most modern station in Europe at the time of its completion in 1975.

On 13 December 1981, Jaruzelski proclaimed martial law, suspended Solidarity, and temporarily imprisoned most of its leaders. This sudden crackdown on Solidarity was reportedly out of fear of Soviet intervention (see Soviet reaction to the Polish crisis of 1980–1981). The government then disallowed Solidarity on 8 October 1982. Martial law was formally lifted in July 1983, though many heightened controls on civil liberties and political life, as well as food rationing, remained in place through the mid-to-late-1980s. Jaruzelski stepped down as prime minister in 1985 and became president (chairman of the Council of State).

This did not prevent Solidarity from gaining more support and power. Eventually it eroded the dominance of the PUWP, which in 1981 lost approximately 85,000 of its 3 million members. Throughout the mid-1980s, Solidarity persisted solely as an underground organization, but by the late 1980s was sufficiently strong to frustrate Jaruzelski’s attempts at reform, and nationwide strikes in 1988 were one of the factors that forced the government to open a dialogue with Solidarity.

From 6 February to 15 April 1989, talks of 13 working groups in 94 sessions, which became known as the «Roundtable Talks» (Rozmowy Okrągłego Stołu) saw the PUWP abandon power and radically altered the shape of the country. In June, shortly after the Tiananmen Square protests in China, the 1989 Polish legislative election took place. Much to its own surprise, Solidarity took all contested (35%) seats in the Sejm, the Parliament’s lower house, and all but one seat in the elected Senate.

Solidarity persuaded the communists’ longtime allied parties, the United People’s Party and Democratic Party, to throw their support to Solidarity. This all but forced Jaruzelski, who had been named president in July, to appoint a Solidarity member as prime minister. Finally, he appointed a Solidarity-led coalition government with Tadeusz Mazowiecki as the country’s first non-communist prime minister since 1948.

On 10 December 1989, the statue of Vladimir Lenin was removed in Warsaw by the PRL authorities.[16]

The Parliament amended the Constitution on 29 December 1989 to formally rescind the PUWP’s constitutionally-guaranteed power and restore democracy and civil liberties. This began the Third Polish Republic, and served as a prelude to the democratic elections of 1991 — the first since 1928.[17]

The PZPR was disbanded on 30 January 1990, but Wałęsa could be elected as president only eleven months later. The Warsaw Pact was dissolved on 1 July 1991 and the Soviet Union ceased to exist in December 1991. On 27 October 1991, the 1991 Polish parliamentary election, the first democratic election since the 1920s. This completed Poland’s transition from a communist party rule to a Western-style liberal democratic political system. The last post-Soviet troops left Poland on 18 September 1993. After ten years of democratic consolidation, Poland joined OECD in 1996, NATO in 1999 and the European Union in 2004.

Government and politics[edit]

The government and politics of the Polish People’s Republic were dominated by the Polish United Workers’ Party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR). Despite the presence of two minor parties, the United People’s Party and the Democratic Party, the country was generally reckoned by western nations as a de facto one-party state because these two parties were supposedly completely subservient to the Communists and had to accept the PZPR’s «leading role» as a condition of their existence.[citation needed] It was politically influenced by the Soviet Union to the extent of being its satellite country, along with East Germany, Czechoslovakia and other Eastern Bloc members.[citation needed]

From 1952, the highest law was the Constitution of the Polish People’s Republic, and the Polish Council of State replaced the presidency of Poland. Elections were held on the single lists of the Front of National Unity. Despite these changes, Poland was one of the most liberal communist nations and was the only communist country in the world which did not have any communist symbols (red star, stars, ears of wheat, or hammer and sickle) on its flag and coat of arms. The White Eagle founded by Polish monarchs in the Middle Ages remained as Poland’s national emblem; the only feature removed by the communists from the pre-war design was the crown, which was seen as imperialistic and monarchist.

The Polish People’s Republic maintained a large standing army and hosted Soviet troops in its territory, as Poland was a Warsaw Pact signatory.[4] The UB and succeeding SB were the chief intelligence agencies that acted as secret police. The official police organization, which was also responsible for peacekeeping and suppression of protests, was renamed Citizens’ Militia (MO). The Militia’s elite ZOMO squads committed various serious crimes to maintain the communists in power, including the harsh treatment of protesters, arrest of opposition leaders and in some cases, murder.[18] According to Rudolph J. Rummel, at least 22,000 people killed by the regime during its rule.[19][page needed] As a result, Poland had a high imprisonment rate but one of the lowest crime rates in the world.[20]

Foreign relations[edit]

During its existence, the Polish People’s Republic maintained relations not only with the Soviet Union, but several communist states around the world. It also had friendly relations with the United States, United Kingdom, France, and the Western Bloc as well as the People’s Republic of China. At the height of the Cold War, Poland attempted to remain neutral to the conflict between the Soviets and the Americans. In particular, Edward Gierek sought to establish Poland as a mediator between the two powers in the 1970s. Both the U.S. presidents and the Soviet general secretaries or leaders visited communist Poland.

Under pressure from the USSR, Poland participated in the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

Poland’s relations with Israel were on a fair level following the aftermath of the Holocaust. In 1947, the PRL voted in favour of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, which led to Israel’s recognition by the PRL on 19 May 1948. However, by the Six-Day War, it severed diplomatic relations with Israel in June 1967 and supported the Palestine Liberation Organization which recognized the State of Palestine on 14 December 1988. In 1989, PRL restored relations with Israel.

The PRL participated as a member of the UN, the World Trade Organization, the Warsaw Pact, Comecon, International Energy Agency, Council of Europe, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, International Atomic Energy Agency, and Interkosmos.

Economy[edit]

Early years[edit]

Poland suffered tremendous economic losses during World War II. In 1939, Poland had 35.1 million inhabitants, but the census of 14 February 1946 showed only 23.9 million inhabitants. The difference was partially the result of the border revision. Losses in national resources and infrastructure amounted to approximately 38%. The implementation of the immense tasks involved with the reconstruction of the country was intertwined with the struggle of the new government for the stabilisation of power, made even more difficult by the fact that a considerable part of society was mistrustful of the communist government. The occupation of Poland by the Red Army and the support the Soviet Union had shown for the Polish communists was decisive in the communists gaining the upper hand in the new Polish government.

Łódź was Poland’s largest city after the destruction of Warsaw during World War II. It was also a major industrial centre in Europe and served as the temporary capital due to its economic significance in the 1940s.

As control of the Polish territories passed from occupying forces of Nazi Germany to the subsequent occupying forces of the Soviet Union, and from the Soviet Union to the Soviet-imposed puppet satellite government, Poland’s new economic system was forcibly imposed and began moving towards a radical, communist centrally planned economy. One of the first major steps in that direction involved the agricultural reform issued by the Polish Committee of National Liberation government on 6 September 1944. All estates over 0.5 km2 in pre-war Polish territories and all over 1 km2 in former German territories were nationalised without compensation. In total, 31,000 km2 of land were nationalised in Poland and 5 million in the former German territories, out of which 12,000 km2 were redistributed to farmers and the rest remained in the hands of the government (Most of this was eventually used in the collectivization and creation of sovkhoz-like State Agricultural Farms «PGR»). However, the collectivization of Polish farming never reached the same extent as it did in the Soviet Union or other countries of the Eastern Bloc.[21]

Female textile workers in a state-run factory, Łódź, 1950s

Nationalisation began in 1944, with the pro-Soviet government taking over industries in the newly acquired territories along with the rest of the country. As nationalization was unpopular, the communists delayed the nationalization reform until 1946, when after the 3xTAK referendums they were fairly certain they had total control of the state and could deal a heavy blow to eventual public protests. Some semi-official nationalisation of various private enterprises had begun also in 1944. In 1946, all enterprises with over 50 employees were nationalised, with no compensation to Polish owners.[22]

The Allied punishment of Germany for the war of destruction was intended to include large-scale reparations to Poland. However, those were truncated into insignificance by the break-up of Germany into East and West and the onset of the Cold War. Poland was then relegated to receive her share from the Soviet-controlled East Germany. However, even this was attenuated, as the Soviets pressured the Polish Government to cease receiving the reparations far ahead of schedule as a sign of ‘friendship’ between the two new communist neighbors and, therefore, now friends.[23][24] Thus, without the reparations and without the massive Marshall Plan implemented in the West at that time, Poland’s postwar recovery was much harder than it could have been.

Later years[edit]

During the Gierek era, Poland borrowed large sums from Western creditors in exchange for promise of social and economic reforms. None of these have been delivered due to resistance from the hardline communist leadership as any true reforms would require effectively abandoning the Marxian economy with central planning, state-owned enterprises and state-controlled prices and trade.[25] After the West refused to grant Poland further loans, the living standards began to sharply fall again as the supply of imported goods dried up, and as Poland was forced to export everything it could, particularly food and coal, to service its massive debt, which would reach US$23 billion by 1980.

In 1981, Poland notified Club de Paris (a group of Western-European central banks) about its insolvency and a number of negotiations of repaying its foreign debt were completed between 1989 and 1991.[26]

The party was forced to raise prices, which led to further large-scale social unrest and formation of the Solidarity movement. During the Solidarity years and the imposition of martial law, Poland entered a decade of economic crisis, officially acknowledged as such even by the regime. Rationing and queuing became a way of life, with ration cards (Kartki) necessary to buy even such basic consumer staples as milk and sugar.[27] Access to Western luxury goods became even more restricted, as Western governments applied economic sanctions to express their dissatisfaction with the government repression of the opposition, while at the same time the government had to use most of the foreign currency it could obtain to pay the crushing rates on its foreign debt.[28]

In response to this situation, the government, which controlled all official foreign trade, continued to maintain a highly artificial exchange rate with Western currencies. The exchange rate worsened distortions in the economy at all levels, resulting in a growing black market and the development of a shortage economy.[29] The only way for an individual to buy most Western goods was to use Western currencies, notably the U.S. dollar, which in effect became a parallel currency. However, it could not simply be exchanged at the official banks for zlotys, since the government exchange rate undervalued the dollar and placed heavy restrictions on the amount that could be exchanged, and so the only practical way to obtain it was from remittances or work outside the country. An entire illegal industry of street-corner money changers emerged as a result. The so-called Cinkciarze gave clients far better than official exchange rate and became wealthy from their opportunism albeit at the risk of punishment, usually diminished by the wide scale bribery of the Militia.[27]

As Western currency came into the country from emigrant families and foreign workers, the government in turn attempted to gather it up by various means, most visibly by establishing a chain of state-run Pewex and Baltona stores in all Polish cities, where goods could only be bought with hard currency. It even introduced its own ersatz U.S. currency (bony PeKaO in Polish).[27] This paralleled the financial practices in East Germany running its own ration stamps at the same time.[27] The trend led to an unhealthy state of affairs where the chief determinant of economic status was access to hard currency. This situation was incompatible with any remaining ideals of socialism, which were soon completely abandoned at the community level.

In this desperate situation, all development and growth in the Polish economy slowed to a crawl. Most visibly, work on most of the major investment projects that had begun in the 1970s was stopped. As a result, most Polish cities acquired at least one infamous example of a large unfinished building languishing in a state of limbo. While some of these were eventually finished decades later, most, such as the Szkieletor skyscraper in Kraków, were never finished at all, wasting the considerable resources devoted to their construction. Polish investment in economic infrastructure and technological development fell rapidly, ensuring that the country lost whatever ground it had gained relative to Western European economies in the 1970s. To escape the constant economic and political pressures during these years, and the general sense of hopelessness, many family income providers traveled for work in Western Europe, particularly West Germany (Wyjazd na saksy).[30] During the era, hundreds of thousands of Poles left the country permanently and settled in the West, few of them returning to Poland even after the end of socialism in Poland. Tens of thousands of others went to work in countries that could offer them salaries in hard currency, notably Libya and Iraq.[31]

After several years of the situation continuing to worsen, during which time the socialist government unsuccessfully tried various expedients to improve the performance of the economy—at one point resorting to placing military commissars to direct work in the factories — it grudgingly accepted pressures to liberalize the economy. The government introduced a series of small-scale reforms, such as allowing more small-scale private enterprises to function. However, the government also realized that it lacked the legitimacy to carry out any large-scale reforms, which would inevitably cause large-scale social dislocation and economic difficulties for most of the population, accustomed to the extensive social safety net that the socialist system had provided. For example, when the government proposed to close the Gdańsk Shipyard, a decision in some ways justifiable from an economic point of view but also largely political, there was a wave of public outrage and the government was forced to back down.

The only way to carry out such changes without social upheaval would be to acquire at least some support from the opposition side. The government accepted the idea that some kind of a deal with the opposition would be necessary, and repeatedly attempted to find common ground throughout the 1980s. However, at this point the communists generally still believed that they should retain the reins of power for the near future, and only allowed the opposition limited, advisory participation in the running of the country. They believed that this would be essential to pacifying the Soviet Union, which they felt was not yet ready to accept a non-Communist Poland.

Culture[edit]

Television and media[edit]

Opening panel and sequence of Dziennik, the chief news program in communist Poland. The famous melody became one of the most recognizable tunes in Polish history.

The origins of Polish television date back to the late 1930s,[32][33] however, the beginning of World War II interrupted further progress at establishing a regularly televised program. The first prime state television corporation, Telewizja Polska, was founded after the war in 1952 and was hailed as a great success by the communist authorities.[34] The foundation date corresponds to the time of the very first regularly televised broadcast which occurred at 07:00 p.m CET on 25 October 1952.[34] Initially, the auditions were broadcast to a limited number of viewers and at set dates, often a month apart. On 23 January 1953 regular shows began to appear on the first and only channel, TVP1.[35] The second channel, TVP2, was launched in 1970 and coloured television was introduced in 1971. Most reliable sources of information in the 1950s were newspapers, most notably Trybuna Ludu (People’s Tribune).

The chief newscast under the Polish People’s Republic for over 31 years was Dziennik Telewizyjny (Television Journal). Commonly known to the viewers as Dziennik, aired in the years 1958–1989 and was utilized by the Polish United Workers’ Party as a propaganda tool to control the masses. Transmitted daily at 07:30 p.m CET since 1965, it was infamous for its manipulative techniques and emotive language as well as the controversial content.[36] For instance, the Dziennik provided more information on world news, particularly bad events, war, corruption or scandals in the West. This method was intentionally used to minimize the effects of the issues that were occurring in communist Poland at the time. With its format, the show shared many similarities with the East German Aktuelle Kamera.[37] Throughout the 1970s, Dziennik Telewizyjny was regularly watched by over 11 million viewers, approximately in every third household in the Polish People’s Republic.[38] The long legacy of communist television continues to this day; the older generation in contemporary Poland refers to every televised news program as «Dziennik» and the term also became synonymous with authoritarianism, propaganda, manipulation, lies, deception and disinformation.[39]

Under martial law in Poland, from December 1981 Dziennik was presented by officers of the Polish Armed Forces or newsreaders in military uniforms and broadcast 24-hours a day.[40][41] The running time has also been extended to 60 minutes. The program returned to its original form in 1983.[42] The audience viewed this move as an attempt to militarize the country under a military junta. As a result, several newsreaders had difficulty in finding employment after the fall of communism in 1989.[41]

Despite the political agenda of Telewizja Polska, the authorities did emphasize the need to provide entertainment for younger viewers without exposing the children to inappropriate content. Initially created in the 1950s, an evening cartoon block called Dobranocka, which was targeted at young children, is still broadcast today under a different format.[43] Among the most well-known animations of the 1970s and 1980s in Poland were Reksio, Bolek and Lolek, Krtek (Polish: Krecik) and The Moomins.[44][45]

Countless shows were made relating to Second World War history such as Four Tank-Men and a Dog (1966–1970) and Stakes Larger Than Life with Kapitan Kloss (1967–1968), but were purely fictional and not based on real events.[46] The horrors of war, Soviet invasion and the Holocaust were taboo topics, avoided and downplayed when possible.[46] In most cases, producers and directors were encouraged to portray the Soviet Red Army as a friendly and victorious force which entirely liberated Poland from Nazism, Imperialism or Capitalism. The goal was to strengthen the artificial Polish-Soviet friendship and eliminate any knowledge of the crimes or acts of terror committed by the Soviets during World War II, such as the Katyn massacre.[47] Hence, the Polish audience were more lenient towards a TV series exclusively featuring Polish history from the times of the Kingdom of Poland or the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

Trybuna Ludu (People’s Tribune) was a government-sponsored newspaper and propaganda outlet

Being produced in a then-socialist country, the shows did contain a socialist agenda, but with a more informal and comical tone; they concentrated on everyday life which was appealing to ordinary people.[48] These include Czterdziestolatek (1975–1978), Alternatywy 4 (1986–1987) and Zmiennicy (1987–1988). The wide range of topics covered featured petty disputes in the block of flats, work issues, human behaviour and interaction as well as comedy, sarcasm, drama and satire.[48] Every televised show was censored if necessary and political content was erased. Ridiculing the communist government was illegal, though Poland remained the most liberal of the Eastern Bloc members and censorship eventually lost its authority by the mid-1980s.[49] The majority of the TV shows and serials made during the Polish People’s Republic earned a cult status in Poland today, particularly due to their symbolism of a bygone era.[46]

Cinema[edit]

In November 1945 the newly formed communist government founded the film production and distribution corporation Film Polski, and placed the well-known Polish filmmaker of Jewish descent Aleksander Ford in charge. The Film Polski output was limited; only thirteen features were released between 1947 and its dissolution in 1952, concentrating on Polish suffering at the hands of the Nazis during World War II for propaganda purposes. In 1947, Ford’s contribution to film was crucial in establishing the new National Film School in Łódź, where he taught for 20 years. The first film produced in Poland following the war was Forbidden Songs (1946), which was seen by 10.8 million people in its initial theatrical screening, almost half of the population at the time.[50] Ford’s biggest success was Knights of the Teutonic Order from 1960, one of the most celebrated and attended Polish films in history.[51]

Andrzej Wajda was a key figure in Polish cinematography during and after the fall of communism

The change in political climate in the 1950s gave rise to the Polish Film School movement, a training ground for some of the icons of the world cinematography. It was then that independent Polish filmmakers such as Andrzej Wajda, Roman Polanski, Wojciech Has, Kieślowski, Zanussi, Bareja and Andrzej Munk often directed films which were a political satire aimed at stultifying the communist authorities in the most gentle manner as possible. However, due to censorship, some films were not screened in cinemas until 1989 when communism ended in Central and Eastern Europe. The Hourglass Sanatorium (1973) was so controversial, the communist government forbade Wojciech Has to direct for a period of ten years.[52] The authorities also hired or bribed film critics and literary scholars to poorly review the film. The reviewers, however, were so ineffective that in turn the film was applauded in the West and won the Jury Prize at the 1973 Cannes Film Festival.[52]

The first nominated Polish film at the Academy Awards was Knife in the Water by Polanski in 1963.[53] Between 1974 and 1981, Polish films were nominated five times and three consecutively from 1974 to 1976.

- Movies

- A Generation

- Ashes and Diamonds

- Nights and Days

- The Deluge

- Knights of the Teutonic Order

- The Quack

- The Doll

- Countess Cosel – Anna Constantia von Brockdorff

- Salt of the Black Earth

- Westerplatte – Battle of Westerplatte

- Death of a President – Assassination of Gabriel Narutowicz

- The Coup d’Etat

- The Cruise

- Sexmission

- Teddy Bear

- How I Unleashed World War II

Architecture[edit]

The architecture in Poland under the Polish People’s Republic had three major phases – short-lived socialist realism, modernism and functionalism. Each of these styles or trends was either imposed by the government or communist doctrine.

Under Stalinism in the late 1940s and 1950s, the Eastern Bloc countries adopted socialist realism, an idealized and monumental realistic art intended to promote communist values, such as the emancipation of the proletariat.[54] This style became alternatively known as Stalinist Empire style due to its grandeur, excessive size and political message (a powerful state) it tried to convey. This expensive form greatly resembled a mixture of classicist architecture and Art Deco, with archways, decorated cornices, mosaics, forged gates and columns.[55][56] It was under this style that the first skyscrapers were erected in communist states. Stalin wanted to assure that Poland will remain under communist yoke and ordered the construction of one of the largest buildings in Europe at the time, the Palace of Culture and Science in Warsaw. With the permission of the Polish authorities who wouldn’t dare to object, the construction started in 1952 and lasted until 1955.[57] It was deemed a «gift from the Soviet Union to the Polish people» and at 237 meters in height it was an impressive landmark on European standards.[57] With its proportions and shape it was to mediate between the Seven Sisters in Moscow and the Empire State Building in New York, but with style it possesses traditionally Polish and Art Deco architectural details.[58][59]

Following the Polish October in 1956, the concept of socialist realism was condemned. It was then that modernist architecture was promoted globally, with simplistic designs made of glass, steel and concrete. Due to previous extravagances, the idea of functionalism (serving for a purpose) was encouraged by Władysław Gomułka. Prefabrication was seen as a way to construct tower blocks or plattenbau in an efficient and orderly manner.[60] A great influence on this type of architecture was Swiss-French architect and designer Le Corbusier.[60] Mass-prefabricated multi-family residential apartment blocks began to appear in Poland in the 1960s and their construction continued until the early 1990s, although the first examples of multi-dwelling units in Poland date back to the 1920s.[60] The aim was to quickly urbanize rural areas, create space between individual blocks for green spaces and resettle people from densely-populated poorer districts to increase living conditions. The apartment blocks in Poland, commonly known as bloki, were built on East German and Czechoslovak standards, alongside department stores, pavilions and public spaces. As of 2017, 44% of Poles reside in blocks built between the 1960s and 1980s.[61]

Some groundbreaking architectural achievements were made during the People’s Republic, most notably the reconstruction of Warsaw with its historical Old Town and the completion of Warszawa Centralna railway station in the 1970s under Edward Gierek’s personal patronage. It was the most modern[62][63] railway station building in that part of Europe when completed and was equipped with automatic glass doors and escalators, an unlikely sight in communist countries.[63] Another example of pure late modernism was the Smyk Department Store, constructed in 1952 when socialist realism was still in effect; it was criticized for its appearance as it resembled the styles and motifs of the pre-war capitalist Second Polish Republic.[64]

Education[edit]

Polish university students during lecture, 1964

Communist authorities placed an emphasis on education since they considered it vital to create a new intelligentsia or an educated class that would accept and favour socialist ideas over capitalism to maintain the communists in power for a long period.

Prior to the Second World War, education in the capitalist Second Polish Republic (1918–1939) had many limitations and wasn’t readily available to all, though under the 1932 Jędrzejewicz reform primary school was made compulsory. Furthermore, the pre-war system of education was in disarray; many educational facilities were much more accessible in wealthier western and central Poland than in the rural east (Kresy), particularly in the Polesie region where there was one large school per 100 square kilometers (39 square miles).[65] Schools were also in desperate need of staff, tutors and teachers before 1939.[65]

After the 1947 Polish legislative election, the communists took full control of the education in the newly formed Polish People’s Republic. All private schools were nationalized, subjects that could question the socialist ideology (economics, finance) were either supervised or adjusted and religious studies were completely removed from the curriculum (secularization).[66]

One of many schools constructed in central Warsaw in the 1960s

Primary as well as secondary, tertiary, vocational and higher education was made free. Attendance gradually grew, which put an end to illiteracy in rural areas. The communist government also introduced new beneficial content into the system; sports and physical education were enforced and students were encouraged to learn foreign languages, especially German, Russian or French and from the 1980s also English. On July 15, 1961, two-year vocational career training was made obligatory to boost the number of skilled labourers and the minimum age of graduation rose to 15. Additionally, special schools were established for deaf, mute and blind children. Such institutions for the impaired were almost nonexistent in the Second Polish Republic. During the 1960s, thousands of modern schools were founded.

The number of universities nearly doubled between 1938 and 1963. Medical, agricultural, economical, engineering and sport faculties became separate colleges, under a universal communist model used in other countries of the Eastern Bloc. Theological faculties were deemed unnecessary or potentially dangerous and were therefore removed from state universities. Philosophy was also seen as superfluous. In order to strengthen the post-war Polish economy, the government created many common-labour faculties across the country, including dairying, fishing, tailoring, chemistry and mechanics to achieve a better economic output alongside efficiency. However, by 1980 the number of graduates from primary and secondary schools was so high that admission quotas for universities were introduced.[66]

Religion[edit]

The experiences in and after World War II, wherein the large ethnic Polish population was decimated, its Jewish minority was annihilated by the Germans, the large German minority was forcibly expelled from the country at the end of the war, along with the loss of the eastern territories which had a significant population of Eastern Orthodox Belarusians and Ukrainians, led to Poland becoming more homogeneously Catholic than it had been.[67]

The Polish anti-religious campaign was initiated by the communist government in Poland which, under the doctrine of Marxism, actively advocated for the disenfranchisement of religion and planned atheisation.[68] The Catholic Church, as the religion of most Poles, was seen as a rival competing for the citizens’ allegiance by the government, which attempted to suppress it.[70] To this effect the communist state conducted anti-religious propaganda and persecution of clergymen and monasteries.[69] As in most other Communist countries, religion was not outlawed as such (an exception being Communist Albania) and was permitted by the constitution, but the state attempted to achieve an atheistic society.

The Catholic Church in Poland provided strong resistance to Communist rule and Poland itself had a long history of dissent to foreign rule.[71] The Polish nation rallied to the Church, as had occurred in neighbouring Lithuania, which made it more difficult for the government to impose its antireligious policies as it had in the USSR, where the populace did not hold mass solidarity with the Russian Orthodox Church. It became the strongest anti-communist body during the epoch of Communism in Poland, and provided a more successful resistance than had religious bodies in most other Communist states.[70]

The Catholic Church unequivocally condemned communist ideology.[72] This led to the antireligious activity in Poland being compelled to take a more cautious and conciliatory line than in other Communist countries, largely failing in their attempt to control or suppress the Polish Church.[71]

The state attempted to take control of minority churches, including the Polish Protestant and Polish Orthodox Church in order to use it as a weapon against the anti-communist efforts of the Roman Catholic Church in Poland, and it attempted to control the person who was named as Metropolitan for the Polish Orthodox Church; Metropolitan Dionizy (the post-war head of the POC) was arrested and retired from service after his release.[73]

Following with the forcible conversion of Eastern Catholics in the USSR to Orthodoxy, the Polish government called on the Orthodox church in Poland to assume ‘pastoral care’ of the eastern Catholics in Poland. After the removal of Metropolitan Dionizy from leadership of the Polish Orthodox Church, Metropolitan Macarius was placed in charge. He was from western Ukraine (previously eastern Poland) and who had been instrumental in the compulsory conversion of eastern Catholics to orthodoxy there. Polish security forces assisted him in suppressing resistance in his taking control of Eastern Catholic parishes.[73] Many eastern Catholics who remained in Poland after the postwar border adjustments were resettled in Western Poland in the newly acquired territories from Germany. The state in Poland gave the POC a greater number of privileges than the Roman Catholic Church in Poland; the state even gave money to this Church, although it often defaulted on promised payments, leading to a perpetual financial crisis for the POC.

Demographics[edit]

A demographics graph illustrating population growth between 1900 and 2010. The highest birth rate was during the Second Polish Republic and consequently under the Polish People’s Republic.

Before World War II, a third of Poland’s population was composed of ethnic minorities. After the war, however, Poland’s minorities were mostly gone, due to the 1945 revision of borders, and the Holocaust. Under the National Repatriation Office (Państwowy Urząd Repatriacyjny), millions of Poles were forced to leave their homes in the eastern Kresy region and settle in the western former German territories. At the same time, approximately 5 million remaining Germans (about 8 million had already fled or had been expelled and about 1 million had been killed in 1944–46) were similarly expelled from those territories into the Allied occupation zones. Ukrainian and Belarusian minorities found themselves now mostly within the borders of the Soviet Union; those who opposed this new policy (like the Ukrainian Insurgent Army in the Bieszczady Mountains region) were suppressed by the end of 1947 in the Operation Vistula.[74][75]

The population of Jews in Poland, which formed the largest Jewish community in pre-war Europe at about 3.3 million people, was all but destroyed by 1945. Approximately 3 million Jews died of starvation in ghettos and labor camps, were slaughtered at the German Nazi extermination camps or by the Einsatzgruppen death squads. Between 40,000 and 100,000 Polish Jews survived the Holocaust in Poland, and another 50,000 to 170,000 were repatriated from the Soviet Union, and 20,000 to 40,000 from Germany and other countries. At its postwar peak, there were 180,000 to 240,000 Jews in Poland, settled mostly in Warsaw, Łódź, Kraków and Wrocław.[76]

According to the national census, which took place on 14 February 1946, population of Poland was 23.9 million, out of which 32% lived in cities and towns, and 68% lived in the countryside. The 1950 census (3 December 1950) showed the population rise to 25 million, and the 1960 census (6 December 1960) placed the population of Poland at 29.7 million.[77] In 1950, Warsaw was again the biggest city, with the population of 804,000 inhabitants. Second was Łódź (pop. 620,000), then Kraków (pop. 344,000), Poznań (pop. 321,000), and Wrocław (pop. 309,000).

Females were in the majority in the country. In 1931, there were 105.6 women for 100 men. In 1946, the difference grew to 118.5/100, but in subsequent years, number of males grew, and in 1960, the ratio was 106.7/100.

Most Germans were expelled from Poland and the annexed east German territories at the end of the war, while many Ukrainians, Rusyns and Belarusians lived in territories incorporated into the USSR. Small Ukrainian, Belarusian, Slovak, and Lithuanian minorities resided along the borders, and a German minority was concentrated near the southwestern city of Opole and in Masuria.[78] Groups of Ukrainians and Polish Ruthenians also lived in western Poland, where they were forcefully resettled by the authorities.

As a result of the migrations and the Soviet Unions radically altered borders under the rule of Joseph Stalin, the population of Poland became one of the most ethnically homogeneous in the world.[79] Virtually all people in Poland claim Polish nationality, with Polish as their native tongue.[80]

Military[edit]

World War II[edit]

The Polish People’s Army (LWP) was initially formed during World War II as the Polish 1st Tadeusz Kościuszko Infantry Division, but more commonly known as the Berling Army. Almost half of the soldiers and recruits in the Polish People’s Army were Soviet.[81] In March 1945, Red Army officers accounted for approximately 52% of the entire corps (15,492 out of 29,372). Around 4,600 of them remained by July 1946.[82]

It was not the only Polish formation that fought along the Allied side, nor the first one in the East – although the first Polish force formed in the USSR, the Anders Army, had by that time moved to Iran. The Polish forces soon grew beyond the 1st Division into two major commands – the Polish First Army commanded by Zygmunt Berling,[83] and the Polish Second Army headed by Karol Świerczewski. The Polish First Army participated in the Vistula–Oder Offensive and the Battle of Kolberg (1945) before taking part in its final offensive with the Battle of Berlin.[83]

After the war[edit]

Following the Second World War, the Polish Army was reorganized into six (later seven) main military districts: the Warsaw Military District with its headquarters in Warsaw, the Lublin Military District, Kraków Military District, Łódź Military District, Poznań Military District, the Pomeranian Military District with its headquarters in Toruń and the Silesian Military District in Katowice.[84]

Throughout the late 1940s and early 50s the Polish Army was under the command of Polish-born Marshal of the Soviet Union Konstantin Rokossovsky, who was intentionally given the title «Marshal of Poland» and was also Minister of National Defense.[85] It was heavily tied into the Soviet military structures and was intended to increase Soviet influence as well as control over the Polish units in case of war. This process, however, was stopped in the aftermath of the Polish October in 1956.[86] Rokossovsky, viewed as a Soviet puppet, was excluded from the Polish United Workers’ Party and driven out back to the Soviet Union where he remained a hero until death.

Geography[edit]

Polish voivodeships after 1957

Polish voivodeships after 1975

Poland’s old and new borders, 1945

Geographically, the Polish People’s Republic bordered the Baltic Sea to the North; the Soviet Union (via the Russian SFSR (Kaliningrad Oblast), Lithuanian, Byelorussian and Ukrainian SSRs) to the east; Czechoslovakia to the south and East Germany to the west. After World War II, Poland’s borders were redrawn, following the decision taken at the Tehran Conference of 1943 at the insistence of the Soviet Union. Poland lost 77,000 km2 of territory in its eastern regions (Kresy), gaining instead the smaller but much more industrialized (however ruined) so-called «Regained Territories» east of the Oder-Neisse line.

Administration[edit]

The Polish People’s Republic was divided into several voivodeships (the Polish unit of administrative division). After World War II, the new administrative divisions were based on the pre-war ones. The areas in the East that were not annexed by the Soviet Union had their borders left almost unchanged. Newly acquired territories in the west and north were organized into the voivodeships of Szczecin, Wrocław, Olsztyn and partially joined to Gdańsk, Katowice and Poznań voivodeships. Two cities were granted voivodeship status: Warsaw and Łódź.

In 1950, new voivodeships were created: Koszalin – previously part of Szczecin, Opole – previously part of Katowice, and Zielona Góra – previously part of Poznań, Wrocław and Szczecin voivodeships. In addition, three other cities were granted the voivodeship status: Wrocław, Kraków and Poznań.

In 1973, Poland’s voivodeships were changed again. This reorganization of the administrative division of Poland was mainly a result of local government reform acts of 1973 to 1975. In place of three-level administrative division (voivodeship, county, commune), a new two-level administrative division was introduced (49 small voidships and communes). The three smallest voivodeships: Warsaw, Kraków and Łódź had a special status of municipal voivodeship; the city mayor (prezydent miasta) was also province governor.

References[edit]

- ^ «Human Development Report 1990» (PDF). hdr.undp.org. January 1990.

- ^ «What Was the Eastern Bloc?». Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ a b Internetowy System Aktow Prawnych (2013). «Small Constitution of 1947» [Mała Konstytucja z 1947]. Original text at the Sejm website. Kancelaria Sejmu RP. Archived from the original (PDF direct download) on 3 June 2015. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ a b c Rao, B. V. (2006), History of Modern Europe Ad 1789-2002: A.D. 1789-2002, Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

- ^ Marek, Krystyna (1954). Identity and Continuity of States in Public International Law. Librairie Droz. p. 475. ISBN 9782600040440.

- ^ «30 procent analfabetów… — Retropress». retropress.pl. 2 March 2014. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ «analfabetyzm — Encyklopedia PWN — źródło wiarygodnej i rzetelnej wiedzy». encyklopedia.pwn.pl.

- ^ «Urząd Bezpieczeństwa Publicznego — Virtual Shtetl». sztetl.org.pl. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ Rummel, R. J. (1997). Statistics of democide: genocide and mass murder since 1900. Charlottesville, Virginia: Transaction Publishers.

- ^ Daems, Tom; Smit, Dirk van Zyl; Snacken, Sonja (17 May 2013). European Penology?. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781782251309. Retrieved 9 July 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Geoffrey K. Roberts, Patricia Hogwood (2013). The Politics Today Companion to West European Politics. Oxford University Press. p. 50. ISBN 9781847790323.; Piotr Stefan Wandycz (1980). The United States and Poland. Harvard University Press. p. 303. ISBN 9780674926851.; Phillip A. Bühler (1990). The Oder-Neisse Line: a reappraisal under international law. East European Monographs. p. 33. ISBN 9780880331746.

- ^ Czesław Osękowski Referendum 30 czerwca 1946 roku w Polsce, Wydawnictwo Sejmowe, 2000, ISBN 83-7059-459-X

- ^ Britannica (10 April 2013), Stefan Wyszyński, (1901–1981). Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Saxon, Wolfgang (29 May 1981). «Wyszynski Fortified Church Under Communist Rule». The New York Times. Retrieved 10 December 2017.

- ^ Curtis, Glenn E., ed. (1992). «The Society: The Polish Catholic Church and the State». Poland: A Country Study. Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Retrieved 10 December 2017 – via Country Studies US.

- ^ «Upheaval in the East; Lenin Statue in Mothballs». New York Times. Reuters. 11 December 1989.

- ^ Millard, Francis (September 1994). «The Shaping of the Polish Party System, 1989-93». East European Politics & Societies. 8 (3): 467–494. doi:10.1177/0888325494008003005.

- ^ «Urząd Bezpieczeństwa Publicznego – Virtual Shtetl». sztetl.org.pl. Archived from the original on 6 January 2020. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ Rummel, Rudolph J. (1997). Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900. Charlottesville, Virginia: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 9783825840105.

- ^ Daems, Tom; Smit, Dirk van Zyl; Snacken, Sonja (17 May 2013). European Penology?. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781782251309. Retrieved 9 July 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Wojciech Roszkowski, Reforma Rolna Encyklopedia.PWN.pl (Internet Archive)

- ^ Zbigniew Landau, Nacjonalizacja w Polsce Encyklopedia.PWN.pl (Internet Archive)

- ^ Billstein, Reinhold; Fings, Karola; Kugler, Anita; Levis, Billstein (October 2004). Working for the enemy: Ford, General Motors, and forced labor in Germany during the Second World War. ISBN 978-1-84545-013-7.

- ^ Hofhansel, Claus (2005). Multilateralism, German foreign policy and Central Europe (Google Books, no preview). ISBN 978-0-415-36406-5. [page needed]

- ^ «Próby reform realnego socjalizmu (gospodarka PRL – 1956–1989)». www.ipsb.nina.gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ «Agreements concluded with Paris Club | Club de Paris». www.clubdeparis.org. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d Karolina Szamańska (2008). «Sklepy w czasach PRL» (PDF). Portal Naukowy Wiedza i Edukacja. pp. 13, 22–23 / 25. Archived from the original (PDF file, direct download) on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Neier, Aryeh (2003). Taking Liberties: Four Decades in the Struggle for Rights. Public Affairs. pp. p. 251. ISBN 1-891620-82-7.

- ^ Jackson, John E.; Jacek Klich; Krystyna Poznanska (2005). The Political Economy of Poland’s Transition: New Firms and Reform Governments. Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–. ISBN 0-521-83895-9.

- ^ «saksy – Wikisłownik, wolny słownik wielojęzyczny». pl.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ «Building Export from Socialist Poland: On the Traces of a Photograph – Stadtaspekte». 2 April 2016. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ «80 lat temu wyemitowano pierwszy w Polsce oficjalny program telewizyjny». www.tvp.info. 26 August 2019.

- ^ «Zapomniany jubileusz TVP». Newsweek.pl. 23 August 2009.

- ^ a b «Symboliczny początek Telewizji Polskiej. Te 30 minut powojenne pokolenie wspomina z łezką w oku». naTemat.pl.

- ^ S.A, Wirtualna Polska Media (23 October 2007). «55. rocznica pierwszej audycji Telewizji Polskiej». wiadomosci.wp.pl.

- ^ «Dziennik Telewizyjny». www.irekw.internetdsl.pl. Archived from the original on 5 December 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ «Aktuelle Kamera – tvpforum.pl». tvpforum.pl.

- ^ «30 lat temu wyemitowano ostatnie wydanie Dziennika Telewizyjnego». wiadomosci.dziennik.pl. 17 November 2019.

- ^ «W mrokach propagandy PRL». histmag.org.

- ^ S.A, Wirtualna Polska Media (11 December 2013). «Dziennikarze w mundurach – Propaganda w stanie wojennym». wiadomosci.wp.pl.

- ^ a b «Gwiazda stanu wojennego pracował jako nocny stróż». www.tvp.info. 13 December 2008.

- ^ «Wyborcza.pl». wyborcza.pl.

- ^ «Kultowe dobranocki wychowały całe pokolenia. Pamiętasz swoją ulubioną?». Portal I.pl. 21 February 2020.

- ^ «Kultowe polskie dobranocki». Culture.pl.

- ^ «Kultowe dobranocki z czasów PRL». wiadomosci.dziennik.pl. 28 June 2009.

- ^ a b c «Najlepsze seriale PRL. «Czterej pancerni», «Czterdziestolatek» i inne kultowe seriale sprzed lat! – Telemagazyn.pl». www.telemagazyn.pl.

- ^ «Niezręczna prawda o «Czterech Pancernych». W rzeczywistości byli… Rosjanami». CiekawostkiHistoryczne.pl.

- ^ a b «Filmy prl, socjalizm – FDB». fdb.pl.

- ^ Burakowska-Ogińska, Lidia (7 March 2011). Był sobie kraj… Polska w publicystyce i eseistyce niemieckiej. Grass – Bienek – Dönhoff. Lidia Burakowska-Oginska. ISBN 9788360902455 – via Google Books.

- ^ Marek Haltof (2002). Polish national cinema. Berghahn Books. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-1-57181-276-6.

- ^ «Wyborcza.pl». lodz.wyborcza.pl.

- ^ a b Piotr Łopuszański. «Poeta polskiego kina – Wojciech Has» [Poet of Polish cinema – Wojciech Has]. Podkowiański Magazyn Kulturalny (in Polish). No. 63.

- ^ «Knife in the Water – Roman Polański». Culture.pl.

- ^ «70 lat temu wprowadzono w Polsce socrealizm jako programowy kierunek sztuki». dzieje.pl.

- ^ «Socrealizm nieoczywisty». Culture.pl.

- ^ «architektura socrealistyczna – cechy stylu». architektura socrealistyczna – cechy stylu – architektura socrealistyczna – cechy stylu – Architektura – Wiedza – HISTORIA: POSZUKAJ.

- ^ a b «Pałac Kultury i Nauki w Warszawie». www.pkin.pl. Archived from the original on 26 January 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ «Pałac Kultury i Nauki». otwartezabytki.pl. Archived from the original on 28 July 2021. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ Kieszek-Wasilewska, Iza (18 December 2013). «Prawdy i legendy o Pałacu Kultury i Nauki». Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ a b c «Skąd się wzięły bloki». Culture.pl.

- ^ «Ponad połowa Polaków mieszka w domach». Onet Biznes. 19 July 2017. Archived from the original on 10 February 2020. Retrieved 7 March 2020.

- ^ «Dworzec Centralny wpisany do rejestru zabytków». www.mwkz.pl.

- ^ a b «Miliardy na budowę. Tak powstawał Dworzec Centralny». TVN Warszawa.

- ^ «Centralny Dom Towarowy». Culture.pl.

- ^ a b «Edukacja w II Rzeczypospolitej». Niepodległa – stulecie odzyskania niepodległości.

- ^ a b «Polska. Oświata. Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa – Encyklopedia PWN – źródło wiarygodnej i rzetelnej wiedzy». encyklopedia.pwn.pl.

- ^ Cieplak, Tadeusz N. (1969). «Church and State in People’s Poland». Polish American Studies. 26 (2): 15–30. JSTOR 20147803.

- ^ Zdzislawa Walaszek. An Open Issue of Legitimacy: The State and the Church in Poland. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 483, Religion and the State: The Struggle for Legitimacy and Power (January 1986), pp. 118–134

- ^ a b Mirek, Agata (2014). «Law as an Instrument of the Communist Authorities in the Fight against Orders in Poland». OL PAN. Teka Komisji Prawniczej: 64–72.

Planned atheisation afflicted all areas of activity of monastic communities […] To victimise clergymen and consecrated people not only provisions of the criminal procedure were used, often violating not only the right for defence, but also basic human rights, allowing to use tortures in order to extort desired testimonies; also an entire system of legal norms, regulating the organisation and functioning of bodies of the judiciary, was used for victimising. Nuns also stood trials in communist courts, becoming victims of the fight of the atheist state against the Catholic Church. The majority of trials from the first decade of the Polish People’s Republic in which nuns were in the dock had a political character. A mass propaganda campaign, saturated with hate, led in the press and on the radio, measured up against defendants, was their distinctive feature.

- ^ a b Dinka, Frank (1966). «Sources of Conflict between Church and State in Poland». The Review of Politics. 28 (3): 332–349. doi:10.1017/S0034670500007130. S2CID 146704335.

- ^ a b Ediger, Ruth M. (2005). «History of an institution as a factor for predicting church institutional behavior: the cases of the Catholic Church in Poland, the Orthodox Church in Romania, and the Protestant churches in East Germany». East European Quarterly. 39 (3).

- ^ Clark, Joanna Rostropowicz (2010). «The Church and the Communist Power». Sarmatian Review. 30 (2).

- ^ a b Wynot, Edward D. Jr. (2002). «Captive faith: the Polish Orthodox Church, 1945–1989». East European Quarterly. 36 (3).

- ^ «Historical documents detailing Vistula operation to deport 150,000 Polish Ukrainians now online -«. 23 May 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ Olchawa, Maciej (2 May 2017). «Ghosts of Operation Vistula». HuffPost. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ «Jews in Poland Since 1939» (PDF) Archived 7 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine, YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, The YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, Yale University Press, 2005

- ^ [Statistical Yearbook of Poland, Warsaw, 1965]

- ^ Schneider, Peter (15 April 1990). «Is Anyone German Here?; A Journey Into Silesia». The New York Times. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ «Poland most homogeneous in EU». Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ «Languages in Poland · Explore which languages are spoken in Poland». languageknowledge.eu. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ «Dr J. Pałka: Ludowe Wojsko Polskie wymyka się prostym klasyfikacjom». Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ Kałużny, Ryszard (2007). «Oficerowie Armii Radzieckiej w wojskach lądowych w Polsce 1945–1956». Zeszyty Naukowe WSOWL (in Polish). AWL (2): 86–87. ISSN 1731-8157.

- ^ a b «21–26 kwietnia 1945 r. – bitwa pod Budziszynem. Hekatomba 2. Armii Wojska Polskiego». 26 April 2016. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ «Śląski Okręg Wojskowy». 14 April 2003. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ «POLAND: Child of the People». Time. 21 November 1949. Retrieved 16 August 2018 – via content.time.com.

- ^ «POLAND: Distrust in the Ranks». Time. 1 July 1957. Retrieved 16 August 2018 – via content.time.com.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ekiert, Grzegorz (March 1997). «Rebellious Poles: Political Crises and Popular Protest Under State Socialism, 1945–89». East European Politics and Societies. American Council of Learned Societies. 11 (2): 299–338. doi:10.1177/0888325497011002006. S2CID 144514807.

- Kuroń, Jacek; Żakowski, Jacek (1995). PRL dla początkujących (in Polish). Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie. pp. 348 pages. ISBN 83-7023-461-5.

- Pucci, M. (14 July 2020). Security Empire: The Secret Police in Communist Eastern Europe. Yale-Hoover Series on Authoritarian Regimes. Yale University Press.[b]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Until the Soviet-Albanian Split in 1961.

- ^ Work covers the secret police in Poland, Czechoslovakia, and East Germany.

Further reading[edit]

External links[edit]

- PRL at Czas-PRL.pl (in Polish)

- Internetowe Muzeum Polski Ludowej at PolskaLudowa.com (in Polish)

- Muzeum PRL Archived 2 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine at MuzeumPRL.com (in Polish)

- Komunizm, socjalizm i czasy PRL-u Archived 3 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine at Komunizm.eu (in Polish)

- Propaganda komunistyczna (in Polish)

- PRL Tube, a categorized collection of videos from the Polish Communist period (in Polish)[dead link]

Coordinates: 52°15′N 18°50′E / 52.250°N 18.833°E

|

Republic of Poland Polish People’s Republic (1952–1989) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947–1989 | ||||||||

|

Flag Coat of arms |

||||||||

| Anthem: Mazurek Dąbrowskiego «Poland Is Not Yet Lost» |

||||||||

The Polish People’s Republic in 1989 |

||||||||

| Status | Warsaw Pact and Comecon member | |||||||

| Capital

and largest city |

Warsaw 52°13′N 21°02′E / 52.217°N 21.033°E |

|||||||

| Official languages | Polish | |||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism (de facto) State atheism (de jure) |

|||||||

| Demonym(s) | Polish, Pole | |||||||

| Government | 1947–1956: Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic under a Stalinist dictatorship 1956–1989: Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic 1981–1983: military junta |

|||||||

| First Secretary and Leader | ||||||||

|

• 1947–1956 (first) |

Bolesław Bierut | |||||||

|

• 1989–1990 (last) |

Mieczysław Rakowski | |||||||

| Head of Council | ||||||||

|

• 1947–1952 (first) |

Bolesław Bierut | |||||||

|

• 1985–1989 (last) |

Wojciech Jaruzelski | |||||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||||

|

• 1944–1947 (first) |

E. Osóbka-Morawski | |||||||

|

• 1989 (last) |

Tadeusz Mazowiecki | |||||||

| Legislature | Sejm | |||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | |||||||

|

• Small Constitution |

19 February 1947 | |||||||

|

• July Constitution |

22 July 1952 | |||||||

|

• Polish October |

21 October 1956 | |||||||

|

• Martial law |

13 December 1981 | |||||||

|

• Free elections |

4 June 1989 | |||||||

|

• Dissolution |

31 December 1989 | |||||||

| Area | ||||||||

|

• Total |

312,685 km2 (120,728 sq mi) | |||||||

| Population | ||||||||

|

• 1989 estimate |

37,970,155 | |||||||

| HDI (1989) | 0.910[1] very high · 33rd |

|||||||

| Currency | Złoty (PLZ) | |||||||

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) | |||||||

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+2 (CEST) | |||||||

| Driving side | right | |||||||

| Calling code | +48 | |||||||

| ISO 3166 code | PL | |||||||

|

The Polish People’s Republic (Polish: Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa, PRL) was a country in Central Europe that existed from 1947 to 1989 as the predecessor of the modern Republic of Poland. With a population of approximately 37.9 million near the end of its existence, it was the second most-populous communist and Eastern Bloc country in Europe.[2] Having a unitary Marxist–Leninist government, it was also one of the main signatories of the Warsaw Pact alliance. The largest city and official capital since 1947 was Warsaw, followed by the industrial city of Łódź and cultural city of Kraków. The country was bordered by the Baltic Sea to the north, the Soviet Union to the east, Czechoslovakia to the south, and East Germany to the west.

Between 1952 and 1989 Poland was ruled by a communist government established after the Red Army’s takeover of Polish territory from German occupation in World War II. The state’s official name was the «Republic of Poland» (Rzeczpospolita Polska) between 1947 and 1952 in accordance with the temporary Small Constitution of 1947.[3] The name «People’s Republic» was introduced and defined by the Constitution of 1952. Like other Eastern Bloc countries (East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Albania),[a] Poland was regarded as a satellite state in the Soviet sphere of interest, but it was never a part of the Soviet Union.[3][4][5]

The Polish United Workers’ Party became the dominant political faction in the Polish People’s Republic, officially making it a socialist country. During this period Poland was a de facto one-party state but it had more liberal policies than other states in the Eastern Bloc and it was characterized by constant internal struggles for democracy. Throughout its existence, economic hardships and social unrest were common in almost every decade. The nation was split between those who supported the party, those who were opposed to it and those who refused to engage in political activity. Despite this, some groundbreaking achievements were established during the People’s Republic such as improved living conditions, rapid industrialization, urbanization, and access to universal health care and education was made available. The birth rate was high and the population almost doubled between 1947 and 1989. The party’s most successful accomplishment was the rebuilding of ruined Warsaw after World War II and the complete eradication of illiteracy.[6][7]

The Polish People’s Army was the main branch of the Armed Forces, though Soviet Army units were also stationed in Poland as in all other Warsaw Pact countries.[4] The UB and succeeding SB were the chief intelligence agencies that acted as secret police, similar to the East German Stasi and Soviet KGB. The official police organization, which was also responsible for supposed peacekeeping and violent suppression of protests, was renamed Citizens’ Militia (MO). The Militia’s elite ZOMO squads committed various serious crimes to maintain the communists in power, including the harsh treatment of protesters, arrest of opposition leaders and in extreme cases, murder,[8] with at least 22,000 people killed by the regime during its rule.[9] As a result, Poland had a high imprisonment rate but one of the lowest crime rates in the world.[10]

History[edit]

1945–1956[edit]

In the summer of 1944 the Polish Committee of National Liberation was established by Soviet-backed Polish communists to control territory retaken from Nazi Germany. On 1 January 1945 the committee was replaced by the Provisional Government of the Republic of Poland, all the key posts of which were held by members of the communist Polish Workers’ Party.

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Stalin was able to present his western allies, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, with a fait accompli in Poland. His armed forces were in occupation of the country, and the communists were in control of its administration. The Soviet Union was in the process of reincorporating the lands to the east of the Curzon Line, which it had invaded and occupied between 1939 and 1941.