Файл формата JPEG открывается специальными программами. Чтобы открыть данный формат, скачайте одну из предложенных программ.

JPEG (полн. Joint Photographic Experts Group) – один из самых распространенных форматов сжатия графических изображений. У JPEG файла практически отсутствуют какие-либо ограничения по числу цветов (как, например, у GIF). Именно благодаря этому он имеет улучшенные параметры конвертации графических фрагментов. Отличительная особенность фотографий на основе JPEG – это наличие яркой цветовой палитры высокого качества.

Ввиду этого формат JPEG сыскал широкую популярность у пользователей различных Интернет-ресурсов. Можно с большой долей вероятности утверждать, что большинство опубликованных в сети Интернет изображений – это файлы с расширением JPEG. Фото JPEG – 42-х битная цветовая палитра, поддерживающая более 16 млн. цветов.

Диапазон степени сжатия градируется от 10:1 до 20:1. Для выбора такого диапазона может быть использована одна из многочисленных графических утилит, например, ACDSee Photo Manager.

Полным аналогом JPEG является расширение JPG. Они основаны практически на идентичном алгоритме сжатия, таким образом, при использовании одной и той же степени конвертации на выходе получатся файлы одинакового объема и качества изображения.

Основное же практическое назначение данного расширения – обработка цифровых изображений, где при традиционно высокой степени конвертации файла, качество графического фрагмента будет на самом высоком уровне.

Присутствуют и свои недостатки: во-первых, с уменьшением размера JPEG файла, увеличивается его степень сжатия и ухудшается качество графики; во-вторых, при обработке формата отсутствует механизм регулировки прозрачности изображения.

Современный JPEG – кроссплатформенный формат, который одинаково хорошо поддерживается на платформе ОС Windows, Mac или Linux.

Программы для открытия JPEG файлов

Чтобы открыть и изменить JPEG расширения на базе платформы ОС Windows можно воспользоваться самыми разнообразными графическими редакторами, в частности:

- Photo Viewer;

- Microsoft Paint;

- Adobe Photoshop;

- Adobe Illustrator;

- CorelDRAW Graphics, Corel PaintShop;

- ACDSee Photo Manager;

- Laughingbird The Logo Creator;

- Roxio Creator;

- Axel Rietschin FastPictureViewer;

- Zoner Photo Studio, IrfanView;

- Adobe Fireworks, PhotoOnWeb;

- Artweaver;

- Ability Photopaint.

Файл JPEG также адаптирован для других ОС, например, в Mac ОС расширение может быть открыто для просмотра Apple Preview, ACDSee Pro for Mac, Roxio Toast, Fireworks for Mac или Flare for Mac.

Но базе платформы ОС Linux JPEG поддерживает работу с GIMP и Gwenview. Также, открыть формат JPEG онлайн может любой интернет-браузер.

Примечательно, что разработчики программных продуктов предусмотрительно позаботились о создании универсального ПО (кроссплатформенного ПО), адаптированного для интеграции на любую ОС: Paint.NET, GIMP, Easy-PhotoPrint EX.

Если при открытии расширения JPEG возникает ошибка, причины могут заключаться в следующем:

- поврежден или инфицирован файл;

- файл не связан с реестром ОС (выбрано некорректное приложение для воспроизведения или не произведена инсталляция конкретного редактора);

- недостаточно ресурсов устройства или ОС;

- поврежденные или устаревшие драйвера.

Конвертация JPEG в другие форматы

JPEG – один из самых неприхотливых для конвертации форматов. Перевод может произвести конвертер JPEG, например, Adobe Photoshop или CorelDRAW.

Также, преобразовать онлайн HEIC файлы в Jpeg можно с помощью сервиса Heic to jpeg (поддерживает русский язык).

С помощью интегрированного в данные графические редакторы транслятора, можно выполнить следующие преобразования форматов:

- JPEG -> DJV;

- JPEG -> ICON;

- JPEG -> DJVU;

- JPEG -> EPS.

- JPEG -> ODG;

- JPEG -> PDF;

- JPEG -> BMP;

- JPEG -> PNG.

- JPEG -> GIF;

- JPEG -> GP5.

Почему именно JPEG и в чем его достоинства?

JPEG – один из самых востребованных среди рядовых пользователей форматов обмена графическими изображениями. Благодаря высокой степени сжатия и сохранению качества графики, JPEG получил широкое распространение как формат, публикуемый на самых разнообразных сайтах и Интернет-ресурсах.

JPEG (произносится «джейпег»[1], англ. Joint Photographic Experts Group, по названию организации-разработчика) — один из популярных растровых графических форматов, применяемый для хранения фотографий и подобных им изображений. Файлы, содержащие данные JPEG, обычно имеют расширения (суффиксы) .jpg (самое популярное), .jfif, .jpe или .jpeg. MIME-тип — image/jpeg.

Фотография заката в формате JPEG с уменьшением степени сжатия слева направо

Алгоритм JPEG позволяет сжимать изображение как с потерями, так и без потерь (режим сжатия lossless JPEG).

Поддерживаются изображения с линейным размером не более 65535 × 65535 пикселов.

В 2010 году с целью сохранения для потомков информации о популярных в начале XXI века цифровых форматах учёные из проекта PLANETS заложили инструкции по чтению формата JPEG в специальную капсулу, которую поместили в специальное хранилище в швейцарских Альпах[2].

Область применения[править | править код]

Алгоритм JPEG наиболее эффективен для сжатия фотографий и картин, содержащих реалистичные сцены с плавными переходами яркости и цвета. Наибольшее распространение JPEG получил в цифровой фотографии и для хранения и передачи изображений с использованием Интернета.

Формат JPEG в режиме сжатия с потерями малопригоден для сжатия чертежей, текстовой и знаковой графики, где резкий контраст между соседними пикселами приводит к появлению заметных артефактов. Такие изображения целесообразно сохранять в форматах без потерь, таких как JPEG-LS, TIFF, GIF, PNG, либо использовать режим сжатия Lossless JPEG.

JPEG (как и другие форматы сжатия с потерями) не подходит для сжатия изображений при многоэтапной обработке, так как искажения в изображения будут вноситься каждый раз при сохранении промежуточных результатов обработки.

JPEG не должен использоваться и в тех случаях, когда недопустимы даже минимальные потери, например при сжатии астрономических или медицинских изображений. В таких случаях может быть рекомендован предусмотренный стандартом JPEG режим сжатия Lossless JPEG (который, однако, не поддерживается большинством популярных кодеков) или стандарт сжатия JPEG-LS.

Сжатие[править | править код]

При сжатии изображение преобразуется из цветового пространства RGB в YCbCr. Стандарт JPEG (ISO/IEC 10918-1) не регламентирует выбор именно YCbCr, допуская и другие виды преобразования (например, с числом компонентов[3], отличным от трёх), и сжатие без преобразования (непосредственно в RGB), однако спецификация JFIF (JPEG File Interchange Format, предложенная в 1991 году специалистами компании C-Cube Microsystems, и ставшая в настоящее время стандартом де-факто) предполагает использование преобразования RGB->YCbCr.

После преобразования RGB->YCbCr для каналов изображения Cb и Cr, отвечающих за цвет, может выполняться «прореживание» (subsampling[4]), которое заключается в том, что каждому блоку из 4 пикселей (2х2) яркостного канала Y ставятся в соответствие усреднённые значения Cb и Cr (схема прореживания «4:2:0»[5]). При этом для каждого блока 2х2 вместо 12 значений (4 Y, 4 Cb и 4 Cr) используется всего 6 (4 Y и по одному усреднённому Cb и Cr). Если к качеству восстановленного после сжатия изображения предъявляются повышенные требования, прореживание может выполняться лишь в каком-то одном направлении — по вертикали (схема «4:4:0») или по горизонтали («4:2:2»), или не выполняться вовсе («4:4:4»).

Пример изображения в формате jpg.

Стандарт допускает также прореживание с усреднением Cb и Cr не для блока 2х2, а для четырёх расположенных последовательно (по вертикали или по горизонтали) пикселей, то есть для блоков 1х4, 4х1 (схема «4:1:1»), а также 2х4 и 4х2 (схема «4:1:0»). Допускается также использование различных типов прореживания для Cb и Cr, но на практике такие схемы применяются исключительно редко.

Далее яркостный компонент Y и отвечающие за цвет компоненты Cb и Cr разбиваются на блоки 8х8 пикселей. Каждый такой блок подвергается дискретному косинусному преобразованию (ДКП). Полученные коэффициенты ДКП квантуются (для Y, Cb и Cr в общем случае используются разные матрицы квантования) и пакуются с использованием кодирования серий и кодов Хаффмана. Стандарт JPEG допускает также использование значительно более эффективного арифметического кодирования, однако из-за патентных ограничений (патент на описанный в стандарте JPEG арифметический QM-кодер принадлежит IBM) на практике оно используется редко. В популярную библиотеку libjpeg последних версий включена поддержка арифметического кодирования, но с просмотром сжатых с использованием этого метода изображений могут возникнуть проблемы, поскольку многие программы просмотра не поддерживают их декодирование.

Матрицы, используемые для квантования коэффициентов ДКП, хранятся в заголовочной части JPEG-файла. Обычно они строятся так, что высокочастотные коэффициенты подвергаются более сильному квантованию, чем низкочастотные. Это приводит к огрублению мелких деталей на изображении. Чем выше степень сжатия, тем более сильному квантованию подвергаются все коэффициенты.

При сохранении изображения в JPEG-файле кодеру указывается параметр качества, задаваемый в некоторых условных единицах, например, от 1 до 100 или от 1 до 10. Большее число обычно соответствует лучшему качеству (и большему размеру сжатого файла). Однако, в самом JPEG-файле такой параметр отсутствует, а качество восстановленного изображения определяется матрицами квантования, типом прореживания цветоразностных компонентов и точностью выполнения математических операций как на стороне кодера, так и на стороне декодера. При этом даже при использовании наивысшего качества (соответствующего матрице квантования, состоящей из одних только единиц, и отсутствию прореживания цветоразностных компонентов) восстановленное изображение не будет в точности совпадать с исходным, что связано как с конечной точностью выполнения ДКП, так и с необходимостью округления значений Y, Cb, Cr и коэффициентов ДКП до ближайшего целого. Режим сжатия Lossless JPEG, не использующий ДКП, обеспечивает точное совпадение восстановленного и исходного изображений, однако его малая эффективность (коэффициент сжатия редко превышает 2) и отсутствие поддержки со стороны разработчиков программного обеспечения не способствовали популярности Lossless JPEG.

Разновидности схем сжатия JPEG[править | править код]

Стандарт JPEG предусматривает два основных способа представления кодируемых данных.

Наиболее распространённым, поддерживаемым большинством доступных кодеков, является последовательное (sequential JPEG) представление данных, предполагающее последовательный обход кодируемого изображения разрядностью 8 бит на компоненту (или 8 бит на пиксель для чёрно-белых полутоновых изображений) поблочно слева направо, сверху вниз. Над каждым кодируемым блоком изображения осуществляются описанные выше операции, а результаты кодирования помещаются в выходной поток в виде единственного «скана», то есть массива кодированных данных, соответствующего последовательно пройденному («просканированному») изображению. Основной или «базовый» (baseline) режим кодирования допускает только такое представление (и хаффмановское кодирование квантованных коэффициентов ДКП). Расширенный (extended) режим наряду с последовательным допускает также прогрессивное (progressive JPEG) представление данных, кодирование изображений разрядностью 12 бит на компоненту/пиксель (сжатие таких изображений спецификацией JFIF не поддерживается) и арифметическое кодирование квантованных коэффициентов ДКП.

В случае progressive JPEG сжатые данные записываются в выходной поток в виде набора сканов, каждый из которых описывает изображение полностью с всё большей степенью детализации. Это достигается либо путём записи в каждый скан не полного набора коэффициентов ДКП, а лишь какой-то их части: сначала — низкочастотных, в следующих сканах — высокочастотных (метод «spectral selection» то есть спектральных выборок), либо путём последовательного, от скана к скану, уточнения коэффициентов ДКП (метод «successive approximation», то есть последовательных приближений). Такое прогрессивное представление данных оказывается особенно полезным при передаче сжатых изображений с использованием низкоскоростных каналов связи, поскольку позволяет получить представление обо всём изображении уже после передачи незначительной части JPEG-файла.

Обе описанные схемы (и sequential, и progressive JPEG) базируются на ДКП и принципиально не позволяют получить восстановленное изображение абсолютно идентичным исходному. Однако стандарт допускает также сжатие, не использующее ДКП, а построенное на основе линейного предсказателя (lossless, то есть «без потерь», JPEG), гарантирующее полное, бит-в-бит, совпадение исходного и восстановленного изображений. При этом коэффициент сжатия для фотографических изображений редко достигает 2, но гарантированное отсутствие искажений в некоторых случаях оказывается востребованным. Заметно большие степени сжатия могут быть получены при использовании не имеющего, несмотря на сходство в названиях, непосредственного отношения к стандарту JPEG ISO/IEC 10918-1 (ITU T.81 Recommendation) метода сжатия JPEG-LS, описываемого стандартом ISO/IEC 14495-1 (ITU T.87 Recommendation).

Синтаксис и структура[править | править код]

Файл JPEG содержит последовательность маркеров, каждый из которых начинается с байта 0xFF, свидетельствующего о начале маркера, и байта-идентификатора. Некоторые маркеры состоят только из этой пары байтов, другие же содержат дополнительные данные, состоящие из двухбайтового поля с длиной информационной части маркера (включая длину этого поля, но за вычетом двух байтов начала маркера, то есть 0xFF и идентификатора) и собственно данных. Такая структура файла позволяет быстро отыскать маркер с необходимыми данными (например, с длиной строки, числом строк и числом цветовых компонентов сжатого изображения).

| Маркер | Байты | Длина | Назначение | Комментарии |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOI | 0xFFD8 | нет | Начало изображения | |

| SOF0 | 0xFFC0 | переменный размер | Начало фрейма (базовый, ДКП) | Показывает, что изображение кодировалось в базовом режиме с использованием ДКП и кода Хаффмана. Маркер содержит число строк и длину строки изображения (двухбайтовые поля со смещением соответственно 5 и 7 относительно начала маркера), количество компонентов (байтовое поле со смещением 9 относительно начала маркера), число бит на компонент — строго 8 (байтовое поле со смещением 4 относительно начала маркера), а также соотношение компонентов (например, 4:2:0). |

| SOF1 | 0xFFC1 | переменный размер | Начало фрейма (расширенный, ДКП, код Хаффмана) | Показывает, что изображение кодировалось в расширенном (extended) режиме с использованием ДКП и кода Хаффмана. Маркер содержит число строк и длину строки изображения, количество компонентов, число бит на компонент (8 или 12), а также соотношение компонентов (например, 4:2:0). |

| SOF2 | 0xFFC2 | переменный размер | Начало фрейма (прогрессивный, ДКП, код Хаффмана) | Показывает, что изображение кодировалось в прогрессивном режиме с использованием ДКП и кода Хаффмана. Маркер содержит число строк и длину строки изображения, количество компонентов, число бит на компонент (8 или 12), а также соотношение компонентов (например, 4:2:0). |

| DHT | 0xFFC4 | переменный размер | Содержит таблицы Хаффмана | Задает одну или более таблиц Хаффмана. |

| DQT | 0xFFDB | переменный размер | Содержит таблицы квантования | Задает одну или более таблиц квантования. |

| DRI | 0xFFDD | 4 байта | Указывает длину рестарт-интервала | Задает интервал между маркерами RST n в макроблоках. При отсутствии DRI появление в потоке кодированных данных маркеров RSTn недопустимо и считается ошибкой. Если при кодировании маркеры RST n не применяются, маркер DRI либо не используется вовсе, либо интервал повторений в нём указывается равным 0. |

| SOS | 0xFFDA | переменный размер | Начало сканирования | Начало первого или очередного скана изображения с направлением обхода слева направо сверху вниз. Если использовался базовый режим кодирования, используется один скан. При использовании прогрессивных режимов используется несколько сканов. Маркер SOS является разделяющим между информативной (заголовком) и закодированной (собственно сжатыми данными) частями изображения. |

| RSTn | 0xFFDn | нет | Перезапуск | Маркеры перезапуска используются для сегментирования кодированных энтропийным кодером данных. В каждом сегменте данные декодируются независимо, что позволяет распараллелить процедуру декодирования. При повреждении кодированных данных в процессе передачи или хранения JPEG-файла использование маркеров перезапуска позволяет ограничить потери (макроблоки из неповреждённых сегментов будут восстановлены правильно). Вставляется в каждом r-м макроблоке, где r — интервал перезапуска DRI маркера. Не используется при отсутствии DRI маркера. n, младшие 3 бита маркера кода, циклы от 0 до 7. |

| APPn | 0xFFEn | переменный размер | Задаётся приложением | Например, в EXIF JPEG-файла используется маркер APP1 для хранения метаданных, расположенных в структуре, основанной на TIFF. |

| COM | 0xFFFE | переменный размер | Комментарий | Содержит текст комментария. |

| EOI | 0xFFD9 | нет | Конец закодированной части изображения. |

Достоинства и недостатки[править | править код]

К недостаткам сжатия по стандарту JPEG следует отнести появление на восстановленных изображениях при высоких степенях сжатия характерных артефактов: изображение рассыпается на блоки размером 8×8 пикселей (этот эффект особенно заметен на областях изображения с плавными изменениями яркости), в областях с высокой пространственной частотой (например, на контрастных контурах и границах изображения) возникают артефакты в виде шумовых ореолов. Стандарт JPEG (ISO/IEC 10918-1, Annex K, п. K.8) предусматривает использование специальных фильтров для подавления блоковых артефактов, но на практике подобные фильтры, несмотря на их высокую эффективность, практически не используются.

Однако, несмотря на недостатки, JPEG получил очень широкое распространение из-за достаточно высокой (относительно существовавших во время его появления альтернатив) степени сжатия, поддержке сжатия полноцветных изображений и относительно невысокой вычислительной сложности.

Скорость сжатия по стандарту JPEG[править | править код]

Для ускорения процесса сжатия по стандарту JPEG традиционно используется распараллеливание вычислений, в частности — при вычислении ДКП. Исторически одна из первых попыток ускорить процесс сжатия с использованием такого подхода описана в опубликованной в 1993 году статье Касперовича и Бабкина[7], в которой предлагалась оригинальная аппроксимация ДКП, делающая возможным эффективное распараллеливание вычислений с использованием 32-разрядных регистров общего назначения процессоров Intel 80386. Появившиеся позже более производительные вычислительные схемы использовали SIMD-расширения набора инструкций процессоров архитектуры x86. Значительно лучших результатов позволяют добиться схемы, использующие вычислительные возможности графических ускорителей (технологии NVIDIA CUDA и AMD FireStream) для организации параллельных вычислений не только ДКП, но и других этапов сжатия JPEG (преобразование цветовых пространств, run-level, статистическое кодирование и т. п.), причём для каждого блока 8х8 кодируемого или декодируемого изображения. В статье[8] была представлена реализация распараллеливания всех стадий алгоритма JPEG по технологии CUDA, что значительно повысило скорость сжатия и декодирования по стандарту JPEG.

См. также[править | править код]

- JPEG-LS

- JPEG 2000

- libjpeg

- MJPEG

- MPEG

- WebP

- GIF

- PNG

- BMP

- WBMP

Примечания[править | править код]

Ссылки[править | править код]

- The JPEG committee homepage

- Спецификация JFIF 1.02 (текстовый файл)

- Различные способы оптимизации JPG файлов практически без потери качества. Источник

- Различные способы открытия JPG файлов. Источник

JPEG (JPG) (правильно произносится как «джейпег») — это растровый графический формат изображений и фотографий с высокой степенью сжатия, который имеет расширения .jpg, .jpe, .jpeg или .jfif. Поддерживает большое количество цветов с глубиной 24 бита. Прежде всего формат необходим, чтобы хранить фото на компьютере и загружать в интернет. С ним изображения занимают мало места, сохраняя при этом высокое качество.

Содержание

- Особенности формата

- Где используется формат JPEG

- Краткая история формата JPEG (JPG)

- JPG и PNG — в чем разница

- Достоинства и недостатки формата JPG

- Программы и сервисы для работы с JPG

- Как открыть поврежденный файл JPG

- Программы, преобразующие JPG в другие форматы

Особенности формата

- Во время сжатия файла есть возможность контролировать потерю качества. Нужно только вручную указать, какой уровень качества вы хотите оставить, когда сохраняете файл в JPEG-формате. Это удобно, если требуется экономить свободное место на диске, поскольку за счет потери качества можно существенно уменьшить размер файла. При этом разница между высоким и очень высоким (100%) качеством не сильно заметна визуально.

- Есть встроенная поддержка EXIF, которая позволяет хранить метаданные: все настройки камеры, заданные на момент съемки.

- Изображения в формате JPG можно создавать и сохранять практически во всех графических редакторах.

- Расширения .jpg и .jpeg работают одинаково.

Где используется формат JPEG

JPG применяется для хранения, обработки и передачи изображения с плавными цветовыми переходами. Под такое определение подходят практически все диджитал-картинки (фотографии, иллюстрации, дизайн-макеты, вайрфреймы и др.), поэтому JPEG — это один из самых распространенных форматов в мире.

В нем сохраняются изображения в цифровых фото- и видеокамерах, в мобильных устройствах, в нем легко выгрузить картинку из любого графического редактора или скриншотера. Если задать настройки внутри камеры, то снимки в формате JPG будут сразу обрабатываться. Можно добавить резкость, насыщенность цвета или снимать черно-белые фото. Файлы в формате JPG удобно размещать или передавать в интернете из-за их небольшого веса.

В каких случаях формат JPG не подойдет:

- если нельзя допустить даже небольшие потери в качестве при сжатии документа;

- если изображение обрабатывается в несколько этапов, поскольку промежуточный результат каждый раз будет сохраняться с небольшим искажением;

- если требуется хранить документы с резким контрастом между пикселями (например, чертежи). Для этого зачастую применяются форматы специализированных чертежных CAD-программ.

Краткая история формата JPEG (JPG)

Первые персональные компьютеры уже умели отображать и хранить цифровые изображения, но универсального способа для этого не существовало. К тому же с отправкой этих файлов с одного компьютера на другой тоже были проблемы. В 1986 году эксперты по фотографии со всего мира собрали комитет, чтобы найти удобный и эффективный способ передавать фото и видео, а также разработать процесс сжатия изображений. Его так и назвали «Объединенная группа экспертов по фотографии» (Joint Photographic Experts Group, сокращенно JPEG). Итогом их работы в 1992 году стало создание единого стандарта сжатия цифровых изображений JPEG с возможностью уменьшать размеры файла. У этой группы даже есть свой сайт.

В 2010 году ученые проекта PLANETS создали капсулу с инструкцией, как прочитать формат JPG. Так наши потомки смогут узнать о популярных в начале XXI столетия цифровых форматах. Поместили капсулу в специально созданное хранилище в Альпах.

JPG и PNG — в чем разница

Оба формата — PNG и JPG — являются основными для изображений, применимых на сайтах и в приложениях. Однако между ними есть некоторые различия, которые определяют, в каких случаях лучше использовать JPG, а в каких — PNG.

В формате JPEG лучше сохранять иллюстрации и фото со множеством цветов и плавным переходом яркости и теней. Также он применим, если нужно передать растровое изображение через интернет и хранить большое количество картинок при ограниченном количестве памяти.

В формате PNG можно без потерь сжимать изображения. Соответственно, в нем лучше сохранять графику с резкой границей, различные рисунки с узорами, текстовую графику, а также некоторые графические элементы, например логотипы или иконки.

Поскольку сжимать файл в PNG можно, не теряя в качестве, его чаще используют для изображений, которые проходят многоэтапную обработку. Файлы в формате PNG могут сохраняться без фона (на прозрачном фоне). Поэтому формат удобно использовать для подстановки на сайт, в рекламные баннеры, для анимации и т.д. Не нужно вырезать фон, в отличие от работы с файлами в JPG, в которых фон есть всегда. Формат PNG отлично подходит, если нужно максимально сохранить детали изображения и не контролировать при этом степень сжатия.

Обобщая, можно сказать, что JPG пригоден в основном для фотографий и многоцветных рисунков, а PNG чаще используется для сохранения плоских иллюстраций, логотипов или иконок.

Достоинства и недостатки формата JPG

К достоинствам формата JPG относятся следующие.

- Он обеспечивает корректную работу с цветными изображениями, в которых много переходов цвета и контрастности.

- Можно самостоятельно настроить размер файла и качество изображения в этом новом размере.

- Его могут распознавать все браузеры и редакторы. Файлы в JPG-формате отображаются на компьютерах и мобильных устройствах без ошибок.

- Имеет малый размер файла, поэтому не занимает много места.

- При незначительном уменьшении размера файла качество почти не ухудшается.

- Огромный выбор цветовой палитры.

Вот недостатки JPG-формата.

- Если существенно уменьшить размер картинки, она может сильно исказиться.

- Восстановленный JPG-файл лучше не редактировать после сжатия. Иначе есть риск потери в качестве просмотра.

- Нельзя сделать фон прозрачным.

- Необратим процесс потери данных во время сжатия.

- Чтобы сохранять детализацию, обязательно надо контролировать степень сжатия.

- Плохо подходит для работы с текстом, слишком контрастным или одноцветным изображением с резкими границами, так как мелкие детали могут пикселизироваться или расплываться. Для этого лучше выбрать другие форматы.

Программы и сервисы для работы с JPG

Если вы не владеете программой Adobe Photoshop, то на помощь могут прийти более простые в освоении аналоги.

- JPEG Wizard. Довольно старая программа, которая работает только с файлами формата JPG. В ней доступны все опции, которые понадобятся, чтобы отредактировать изображение. Есть возможность повернуть, обрезать снимок, поменять его разрешение, настроить цветопередачу. Выбранные картинки можно преобразовать в коллажи. Как только с файлом произойдут какие-то изменения в программе, его размер пересчитается. Большой объем файлов можно редактировать пакетом Batch Editor.

- FastPictureViewer. Платная программа с несложными настройками. Подойдет для фотографов и фоторедакторов. Позволяет работать с почти всеми размерами фотографий. Просмотр, копирование, резервирование, перемещение и удаление файлов можно совершать одновременно. Программа поддерживает много графических форматов, а если подключить дополнительные кодексы, будут доступны специальные форматы типа DDS, PNM и другие. Здесь можно профессионально управлять цветом с помощью ICC v2- и v4-профилей. Доступен 30-дневный пробный период, по окончании которого программа перейдет в режим базовой хоум-версии с ограниченным функционалом.

- PhotoScape. Бесплатный редактор, упрощенная альтернатива Photoshop. В программе широкий выбор инструментов, позволяющих редактировать и обрабатывать изображения, в том числе кисти. Вы сможете изменить размер, добавить надпись, установить светотеневой баланс. Работайте не только с фотографиями, но и со скриншотами. Из нескольких снимков даже возможно создать анимацию. Имеет интуитивно понятный интерфейс, в котором легко ориентироваться даже новичку. Если ваши файлы изначально в формате RAW, их можно быстро конвертировать в JPG.

- Paint.net. Еще один бесплатный редактор для обработки. Входит в пакет Microsoft.net, поэтому в дополнительной установке не нуждается. У него больше возможностей, если сравнивать с классическим MS Paint. В программе большой каталог фильтров и различных эффектов, например размытие. Есть возможность изменять масштаб изображения, управлять слоями, работать с камерой и сканерами. Поддерживается планшетными компьютерами.

- JPEG Compressor. Позволяет сжимать цифровые изображения в формате JPG в компактные форматы. Это удобно, если вы работаете с фото высокой четкости или если несколько файлов отправляются сразу многим получателям. При этом качество исходного изображения не пострадает. Изменять файлы можно и пакетно.

Как открыть поврежденный файл JPG

Иногда JPG-формат повреждается. На это могут влиять какие-либо ошибки или сбои в программном обеспечении, вирусные атаки, сетевые ошибки или отказ операционной системы.

Если во время запуска файла через программу просмотра изображений выходит ошибка с записью «Файл поврежден», если файл вообще не открывается или открывается с повреждениями — для его восстановления лучше использовать специальные программы.

- Новичкам подойдет сервис officerecovery. Работать с ним довольно просто. Нажимаем кнопку «Выбрать файл» и находим поврежденный файл на компьютере. Далее восстанавливаем документ через кнопку «Безопасная загрузка и восстановление». У сервиса есть бесплатные и платные возможности загрузки файла после процесса восстановления.

- Еще одна программа — Hetman File Repair. Она предназначена для ПК. Позволяет быстро и безопасно восстановить изображения и фотографии. Сначала у вас будет возможность проверить, насколько эффективно программа сработает в вашем случае. Также есть опция предварительного просмотра восстановленного файла. Если результаты бесплатной версии вас устроят, нужно зарегистрировать программу, чтобы использовать ее дальше.

- Если файлы повредились при сжатии, можно воспользоваться программой UnJPEG. Позволяет устранить некоторые проблемы (артефакты), а также повысить четкость изображения. Еще в UnJPEG есть фильтр, позволяющий устранять случайные шумы. Программа распознает, чем является изображение (неудачно сжатое фото или рисунок, который плохо сохранили), и на этом основании ищет артефакты в файле.

Программы, преобразующие JPG в другие форматы

- JPEG Compressor. Упомянутая ранее программа может не только сжимать изображения, но и конвертировать JPG-файлы в другие популярные форматы, например GIF и BMP.

- FileZigZag. Сервис конвертации изображений, работающий в режиме онлайн. Большое количество как входных форматов, так и тех, в которые программа преобразует. Нужно загрузить исходный файл и выбрать формат, в который нужно конвертировать. Остается дождаться ссылки на готовое изображение. Обычно много времени процесс конвертации не занимает, исключение — файлы большого размера.

Интерфейс FileZigZag интуитивно понятен: выбираем файл, конечный формат и жмем на зеленую кнопку конвертации

- ZamZar. Тоже работает в онлайн-режиме. Поддерживает более 1000 известных форматов. Помимо фото конвертирует документы и видео. От некоторых других конвертеров отличается медленным процессом преобразования файлов. Работает с 2006 года.

- Adapter. Программа не только помогает изменить форматы фотографий и других изображений, видео- и аудиофайлов, но также имеет несколько удобных опций. Например, можно изменить разрешение и качество снимков, а также наложить на них текст. Сервис работает очень быстро. Подходит для установки на Windows и Mac.

- CoffeeCup PixConverter. Бесплатный онлайн-конвертер изображений. Им удобно пользоваться. Помимо конвертации изображение можно еще и редактировать: повернуть, изменить размер или цвет. В программу одновременно можно загрузить несколько фотографий.

- BatchPhoto Espresso. Этот бесплатный редактор работает на любой ОС. Позволяет конвертировать изображения, размер которых не больше 10 Мб. Прежде чем сохранить преобразованный файл, его можно переименовать, выбрать для него размер или приемлемое качество. В BatchPhoto Espresso есть инструменты, с которыми можно поменять яркость или контрастность, а также эффект скручивания и некоторые другие.

- CoolUtils. С этой программой файлы преобразуются в режиме реального времени, вам не придется ждать ссылку на почту для скачивания готового файла. Перед конвертацией изображение можно повернуть или поменять его размер.

JPG – часто используемый графический формат сжатого изображения, разработанный компанией Joint Photo…

JPG – часто используемый графический формат сжатого изображения, разработанный компанией Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG). Файлы имеют высокий уровень сжатия и поддерживают глубину цвета в 24 бит. Благодаря этим характеристикам файлы с расширениями JPG/JPEG применяются в цифровых фотоаппаратах, смартфонах, видеокамерах. Несмотря на распространенность формата, у некоторых пользователей возникает вопрос – чем открыть JPG? Рассмотрим различные варианты и возможные сложности.

Область применения и свойства формата jpg

Формат JPG чаще применяется для хранения, обработки и передачи картинок с цветовыми и контрастными переходами. Подходит для размещения в интернете. В смартфонах, цифровых фотоаппаратах и видеокамерах изображения хранятся в этом формате, это обусловлено минимальным заполнением объема памяти и качеством на выходе.

Положительные и отрицательные характеристики файла формата jpg

К плюсам формата относятся:

- Широкий диапазон уровня сжатия (качество и размер файла зависят от степени сжатия).

- Минимальный размер файла.

- Согласованность с браузерами и текстовыми редакторами.

- Отображение на современных устройствах.

- При невысоком уровне сжатия не страдает качество картинки.

Благодаря этим характеристикам, формат завоевал популярность, как у пользователей, так и у продвинутых программистов.

Минусы:

- При достаточном уровне сжатия может «развалиться» на блоки пикселей.

- Не поддерживает прозрачность.

- Не рекомендуется редактировать файл после восстановления. Каждая новая манипуляция снижает качество изображения.

Чем и как открывать файлы jpg

Изображения JPG используются повсеместно, поэтому программа для просмотра JPG входит в набор для стандартных опций Windows. В случае, если программа для просмотра фотографий JPG не встроена в операционную систему, файл можно открыть в Microsoft Paint, который есть в списке стандартных программ для Windows.

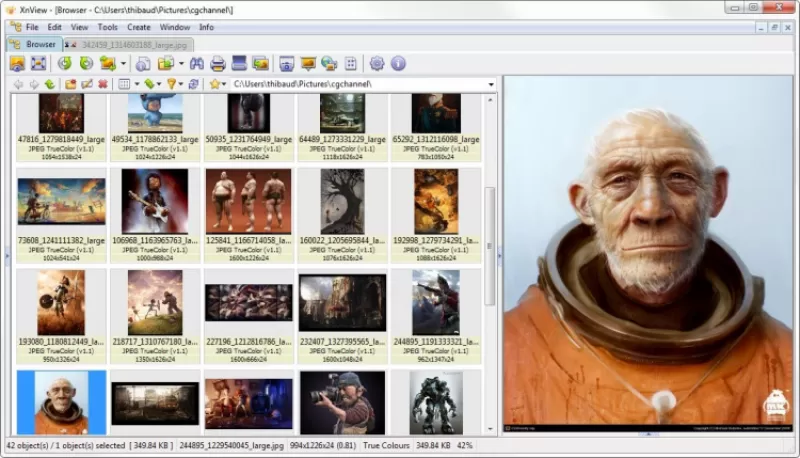

Открываем на компьютере

У рядового пользователя обычно не возникает проблем с вопросом, как открыть файл JPG на компьютере. Большое распространение получили программы для jpg/jpeg файлов. Вот некоторые из них:

- STDU Viewer.

- Faststone Image Viewer.

- XnView.

- Picasa.

Скачать программу для просмотра jpg можно в сети интернет, если она есть в свободном доступе, либо купить лицензионную версию у разработчика. Каждая из них имеет особенности работы с jpg/jpeg файлами.

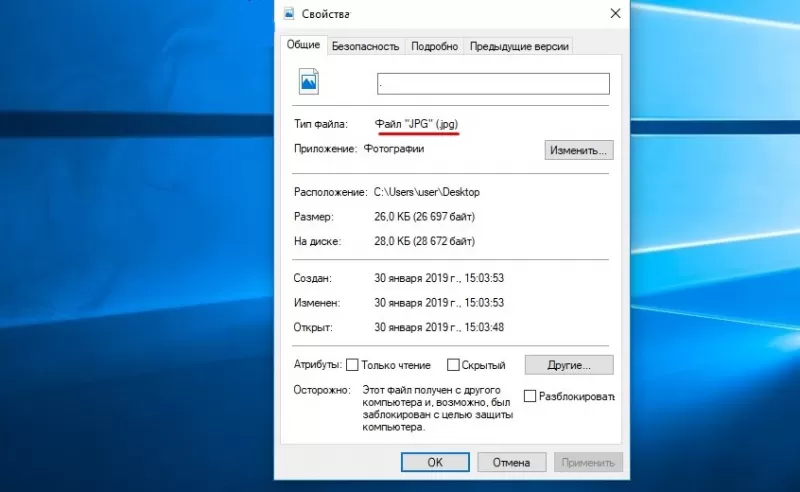

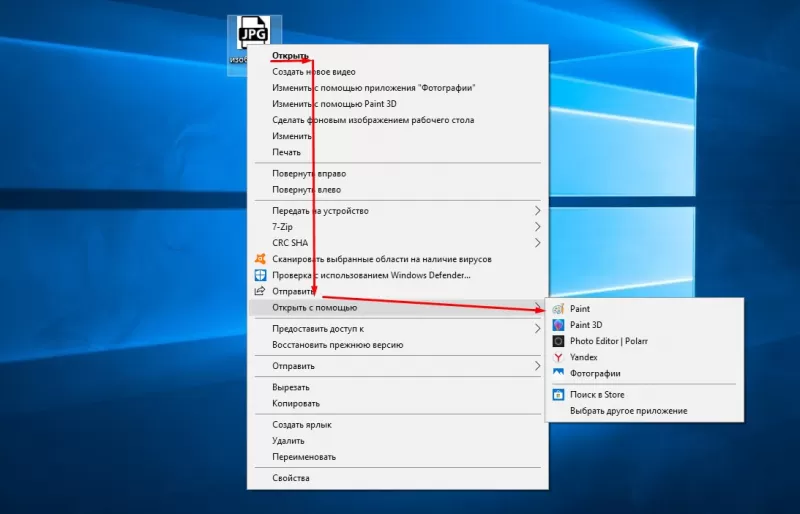

Открыть формат через Windows 10

Программа для просмотра JPG для Windows 10 отсутствует в базовом ПО. Однако в случае смены ОС с Windows 7 или 8.1, средство просмотра фотографий может присутствовать на ПК. Существует способ удостовериться, что программы для открытия jpg файлов установлены. Для этого кликните на изображение правой кнопкой мыши и найдите пункт «Открыть с помощью». Далее просмотрите список предложенных средств для просмотра.

Воспользуйтесь программой для открытия JPG WinAero Tweaker. После запуска утилиты, перейдите в раздел «Windows Accessories» и выберите пункт «Activate Windows Photo Viewer».

Просмотреть с помощью Windows 7

В Windows 7 сразу установлено ПО, которое открывает разноформатные файлы, в том числе и JPG. Если же установлено больше 2-х программ для просмотра и открытия файлов JPG, при двойном щелчке мышки на изображении, откроется программа, установленная по умолчанию. Чтобы открыть формат JPG другой программой из меню «Проводника», выбрать и нажать на кнопку «Открыть с помощью…».

Онлайн-просмотр

Открыть файл JPG онлайн и просмотреть фото можно популярными программами:

- Apple Фото.

- Microsoft OneDrive.

- Google Диск.

Как открыть поврежденный файл jpg?

Как определить, что файл JPG поврежден? При попытке запуска появляется ошибка (диалоговое окно с сообщением «файл поврежден») или же не открывается вовсе. Тогда используют программы RS File Repair, PixRecovery, JPEGfix для восстановления файлов. Большинство таких программ можно бесплатно скачать в интернете.

| Расширение |

|

|---|---|

| MIME |

|

| Сигнатура |

0xFF 0xD8 |

| Опубликован |

1991 год |

| Развит в |

JPEG 2000, JPEG XR, MotionJPEG |

JPEG (произносится «джейпег»[1], англ. Joint Photographic Experts Group, по названию организации-разработчика) — один из популярных графических форматов, применяемый для хранения фотоизображений и подобных им изображений. Файлы, содержащие данные JPEG, обычно имеют расширения (суффиксы) .jpeg, .jfif, .jpg, .JPG, или .JPE. Однако из них .jpg является самым популярным на всех платформах. MIME-типом является image/jpeg.

Фотография заката в формате JPEG с уменьшением степени сжатия слева направо

Алгоритм JPEG позволяет сжимать изображение как с потерями, так и без потерь (режим сжатия lossless JPEG). Поддерживаются изображения с линейным размером не более 65535 × 65535 пикселей.

Содержание

- 1 Область применения

- 1.1 Сжатие

- 1.2 Разновидности схем сжатия JPEG

- 2 Синтаксис и структура

- 3 Достоинства и недостатки

- 4 Производительность сжатия по стандарту JPEG

- 5 Интересные факты

- 6 См. также

- 7 Примечания

- 8 Ссылки

Область применения

Алгоритм JPEG в наибольшей степени пригоден для сжатия фотографий и картин, содержащих реалистичные сцены с плавными переходами яркости и цвета. Наибольшее распространение JPEG получил в цифровой фотографии и для хранения и передачи изображений с использованием сети Интернет.

С другой стороны, JPEG малопригоден для сжатия чертежей, текстовой и знаковой графики, где резкий контраст между соседними пикселами приводит к появлению заметных артефактов. Такие изображения целесообразно сохранять в форматах без потерь, таких как TIFF, GIF или PNG.

JPEG (как и другие методы искажающего сжатия) не подходит для сжатия изображений при многоступенчатой обработке, так как искажения в изображения будут вноситься каждый раз при сохранении промежуточных результатов обработки.

JPEG не должен использоваться и в тех случаях, когда недопустимы даже минимальные потери, например, при сжатии астрономических или медицинских изображений. В таких случаях может быть рекомендован предусмотренный стандартом JPEG режим сжатия Lossless JPEG (который, однако, не поддерживается большинством популярных кодеков) или стандарт сжатия JPEG-LS.

Сжатие

При сжатии изображение преобразуется из цветового пространства RGB в YCbCr (YUV). Следует отметить, что стандарт JPEG (ISO/IEC 10918-1) никак не регламентирует выбор именно YCbCr, допуская и другие виды преобразования (например, с числом компонентов[2], отличным от трёх), и сжатие без преобразования (непосредственно в RGB), однако спецификация JFIF (JPEG File Interchange Format, предложенная в 1991 году специалистами компании C-Cube Microsystems, и ставшая в настоящее время стандартом де-факто) предполагает использование преобразования RGB->YCbCr.

После преобразования RGB->YCbCr для каналов изображения Cb и Cr, отвечающих за цвет, может выполняться «прореживание» (subsampling[3]), которое заключается в том, что каждому блоку из 4 пикселов (2х2) яркостного канала Y ставятся в соответствие усреднённые значения Cb и Cr (схема прореживания «4:2:0»[4]). При этом для каждого блока 2х2 вместо 12 значений (4 Y, 4 Cb и 4 Cr) используется всего 6 (4 Y и по одному усреднённому Cb и Cr). Если к качеству восстановленного после сжатия изображения предъявляются повышенные требования, прореживание может выполняться лишь в каком-то одном направлении — по вертикали (схема «4:4:0») или по горизонтали («4:2:2»), или не выполняться вовсе («4:4:4»).

Стандарт допускает также прореживание с усреднением Cb и Cr не для блока 2х2, а для четырёх расположенных последовательно (по вертикали или по горизонтали) пикселов, то есть для блоков 1х4, 4х1 (схема «4:1:1»), а также 2х4 и 4х2 (схема «4:1:0»). Допускается также использование различных типов прореживания для Cb и Cr, но на практике такие схемы применяются исключительно редко.

Далее яркостный компонент Y и отвечающие за цвет компоненты Cb и Cr разбиваются на блоки 8х8 пикселов. Каждый такой блок подвергается дискретному косинусному преобразованию (ДКП). Полученные коэффициенты ДКП квантуются (для Y, Cb и Cr в общем случае используются разные матрицы квантования) и пакуются с использованием кодирования серий и кодов Хаффмана. Стандарт JPEG допускает также использование значительно более эффективного арифметического кодирования, однако из-за патентных ограничений (патент на описанный в стандарте JPEG арифметический QM-кодер принадлежит IBM) на практике оно используется редко. В популярную библиотеку libjpeg последних версий включена поддержка арифметического кодирования, но с просмотром сжатых с использованием этого метода изображений могут возникнуть проблемы, поскольку многие программы просмотра не поддерживают их декодирование.

Матрицы, используемые для квантования коэффициентов ДКП, хранятся в заголовочной части JPEG-файла. Обычно они строятся так, что высокочастотные коэффициенты подвергаются более сильному квантованию, чем низкочастотные. Это приводит к огрублению мелких деталей на изображении. Чем выше степень сжатия, тем более сильному квантованию подвергаются все коэффициенты.

При сохранении изображения в JPEG-файле указывается параметр качества, задаваемый в некоторых условных единицах, например, от 1 до 100 или от 1 до 10. Большее число обычно соответствует лучшему качеству (и большему размеру сжатого файла). Однако даже при использовании наивысшего качества (соответствующего матрице квантования, состоящей из одних только единиц) восстановленное изображение не будет в точности совпадать с исходным, что связано как с конечной точностью выполнения ДКП, так и с необходимостью округления значений Y, Cb, Cr и коэффициентов ДКП до ближайшего целого. Режим сжатия Lossless JPEG, не использующий ДКП, обеспечивает точное совпадение восстановленного и исходного изображений, однако его малая эффективность (коэффициент сжатия редко превышает 2) и отсутствие поддержки со стороны разработчиков программного обеспечения не способствовали популярности Lossless JPEG.

Разновидности схем сжатия JPEG

Стандарт JPEG предусматривает два основных способа представления кодируемых данных.

Наиболее распространённым, поддерживаемым большинством доступных кодеков, является последовательное (sequential JPEG) представление данных, предполагающее последовательный обход кодируемого изображения поблочно слева направо, сверху вниз. Над каждым кодируемым блоком изображения осуществляются описанные выше операции, а результаты кодирования помещаются в выходной поток в виде единственного «скана», то есть массива кодированных данных, соответствующего последовательно пройденному («просканированному») изображению. Основной или «базовый» (baseline) режим кодирования допускает только такое представление. Расширенный (extended) режим наряду с последовательным допускает также прогрессивное (progressive JPEG) представление данных.

В случае progressive JPEG сжатые данные записываются в выходной поток в виде набора сканов, каждый из которых описывает изображение полностью с всё большей степенью детализации. Это достигается либо путём записи в каждый скан не полного набора коэффициентов ДКП, а лишь какой-то их части: сначала — низкочастотных, в следующих сканах — высокочастотных (метод «spectral selection» то есть спектральных выборок), либо путём последовательного, от скана к скану, уточнения коэффициентов ДКП (метод «successive approximation», то есть последовательных приближений). Такое прогрессивное представление данных оказывается особенно полезным при передаче сжатых изображений с использованием низкоскоростных каналов связи, поскольку позволяет получить представление обо всём изображении уже после передачи незначительной части JPEG-файла.

Обе описанные схемы (и sequential, и progressive JPEG) базируются на ДКП и принципиально не позволяют получить восстановленное изображение абсолютно идентичным исходному. Однако стандарт допускает также сжатие, не использующее ДКП, а построенное на основе линейного предсказателя (lossless, то есть «без потерь», JPEG), гарантирующее полное, бит-в-бит, совпадение исходного и восстановленного изображений. При этом коэффициент сжатия для фотографических изображений редко достигает 2, но гарантированное отсутствие искажений в некоторых случаях оказывается востребованным. Заметно большие степени сжатия могут быть получены при использовании не имеющего, несмотря на сходство в названиях, непосредственного отношения к стандарту JPEG ISO/IEC 10918-1 (ITU T.81 Recommendation) метода сжатия JPEG-LS, описываемого стандартом ISO/IEC 14495-1 (ITU T.87 Recommendation).

Синтаксис и структура

Файл JPEG содержит последовательность маркеров, каждый из которых начинается с байта 0xFF, свидетельствующего о начале маркера, и байта-идентификатора. Некоторые маркеры состоят только из этой пары байтов, другие же содержат дополнительные данные, состоящие из двухбайтового поля с длиной информационной части маркера (включая длину этого поля, но за вычетом двух байтов начала маркера то есть 0xFF и идентификатора) и собственно данных. Такая структура файла позволяет быстро отыскать маркер с необходимыми данными (например, с длиной строки, числом строк и числом цветовых компонентов сжатого изображения).

| Маркер | Байты | Длина | Назначение | Комментарии |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOI | 0xFFD8 | нет | Начало изображения | |

| SOF0 | 0xFFC0 | переменный размер | Начало фрейма (базовый, ДКП) | Показывает что изображение кодировалось в базовом режиме с использованием ДКП и кода Хаффмана. Маркер содержит число строк и длину строки изображения (двухбайтовые поля со смещением соответственно 5 и 7 относительно начала маркера), количество компонентов (байтовое поле со смещением 8 относительно начала маркера), число бит на компонент (байтовое поле со смещением 4 относительно начала маркера), а также соотношение компонентов (например, 4:2:0). |

| SOF1 | 0xFFC1 | переменный размер | Начало фрейма (расширенный, ДКП, код Хаффмана) | Показывает что изображение кодировалось в расширенном (extended) режиме с использованием ДКП и кода Хаффмана. Маркер содержит число строк и длину строки изображения, количество компонентов, число бит на компонент, а также соотношение компонентов (например, 4:2:0). |

| SOF2 | 0xFFC2 | переменный размер | Начало фрейма (прогрессивный, ДКП, код Хаффмана) | Показывает что изображение кодировалось в прогрессивном режиме с использованием ДКП и кода Хаффмана. Маркер содержит число строк и длину строки изображения, количество компонентов, число бит на компонент, а также соотношение компонентов (например, 4:2:0). |

| DHT | 0xFFC4 | переменный размер | Содержит таблицы Хаффмана | Задает одну или более таблиц Хаффмана. |

| DQT | 0xFFDB | переменный размер | Содержит таблицы квантования | Задает одну или более таблиц квантования. |

| DRI | 0xFFDD | 4 байта | Указывает интервал повторений | Задает интервал между маркерами RST n в макроблоках. |

| SOS | 0xFFDA | переменный размер | Начало сканирования | Начало первого или очередного скана изображения с направлением обхода слева направо сверху вниз. Если использовался базовый режим кодирования, используется один скан. При использовании прогрессивных режимов используется несколько сканов. Маркер SOS является разделяющим между информативной (заголовком) и закодированной (собственно сжатыми данными) частями изображения. |

| RSTn | 0xFFDn | нет | Перезапуск | Вставляется в каждом r макроблоке, где r — интервал перезапуска DRI маркера. Не используется при отсутствии DRI маркера. n, младшие 3 бита маркера кода, циклы от 0 до 7. |

| APPn | 0xFFEn | переменный размер | Задаётся приложением | Например, в EXIF JPEG-файла используется маркер APP1 для хранения метаданных, расположеных в структуре, основанной на TIFF. |

| COM | 0xFFFE | переменный размер | Комментарий | Содержит текст комментария. |

| EOI | 0xFFD9 | нет | Конец закодированной части изображения. |

Достоинства и недостатки

К недостаткам сжатия по стандарту JPEG следует отнести появление на восстановленных изображениях при высоких степенях сжатия характерных артефактов: изображение рассыпается на блоки размером 8×8 пикселов (этот эффект особенно заметен на областях изображения с плавными изменениями яркости), в областях с высокой пространственной частотой (например, на контрастных контурах и границах изображения) возникают артефакты в виде шумовых ореолов. Следует отметить, что стандарт JPEG (ISO/IEC 10918-1, Annex K, п. K.8) предусматривает использование специальных фильтров для подавления блоковых артефактов, но на практике подобные фильтры, несмотря на их высокую эффективность, практически не используются. Однако, несмотря на недостатки, JPEG получил очень широкое распространение из-за достаточно высокой (относительно существовавших во время его появления альтернатив) степени сжатия, поддержке сжатия полноцветных изображений и относительно невысокой вычислительной сложности.

Производительность сжатия по стандарту JPEG

Для ускорения процесса сжатия по стандарту JPEG традиционно используется распараллеливание вычислений, в частности — при вычислении ДКП. Исторически одна из первых попыток ускорить процесс сжатия с использованием такого подхода описана в опубликованной в 1993 г. статье Касперовича и Бабкина [6], в которой предлагалась оригинальная аппроксимация ДКП, делающая возможным эффективное распараллеливание вычислений с использованием 32-разрядных регистров общего назначения процессоров Intel 80386. Появившиеся позже более производительные вычислительные схемы использовали SIMD-расширения набора инструкций процессоров архитектуры x86. Значительно лучших результатов позволяют добиться схемы, использующие вычислительные возможности графических ускорителей (технологии NVIDIA CUDA и AMD FireStream) для организации параллельных вычислений не только ДКП, но и других этапов сжатия JPEG (преобразование цветовых пространств, run-level, статистическое кодирование и т.п.), причём для каждого блока 8х8 кодируемого или декодируемого изображения. В статье [7] была впервые[источник?] представлена реализация распараллеливания всех стадий алгоритма JPEG по технологии CUDA, что значительно ускорило производительность сжатия и декодирования по стандарту JPEG.

Интересные факты

В 2010 году ученые из проекта PLANETS поместили инструкции по чтению формата JPEG в специальную капсулу, которую поместили в специальный бункер в швейцарских Альпах. Сделано это было с целью сохранения для потомков информации о популярных в начале XXI века цифровых форматах.[8]

См. также

- JPEG-LS

- JPEG2000

- libjpeg

- MJPEG

- MPEG

- WebP

Примечания

- ↑ JPEG pronounced — Поиск в Google

- ↑ В соответствии с ГОСТ 34.003-90 в области информационных технологий данный термин имеет мужской род

- ↑ ISO/IEC 10918-1 : 1993(E) p.28. Архивировано из первоисточника 22 августа 2011.

- ↑ Kerr, Douglas A. «Chrominance Subsampling in Digital Images»

- ↑ ISO/IEC 10918-1 : 1993(E) p.36. Архивировано из первоисточника 22 августа 2011.

- ↑ Kasperovich, L.V., Babkin, V.F. «Fast discrete cosine transform approximation for JPEG image compression»

- ↑ «Использование технологии CUDA для быстрого сжатия изображений по алгоритму JPEG»

- ↑ Ученые законсервировали для потомков форматы JPEG и PDF. Проверено 21 мая 2010.

Ссылки

- The JPEG committee homepage

- Спецификация JFIF 1.02 (текстовый файл)

- Оптимизация JPEG. Часть 1, Часть 2, Часть 3.

- Быстрое сжатие JPEG на видеокарте.

| |

|

|---|---|

| Видео/аудио |

3GP • ASF • AVI • Bink • DMF • DPX • EVO • FLV • Matroska (MKV) • WebM • MPEG-PS • MPEG-TS • MP4 • MXF • NUT • Ogg • Ogg Media • QuickTime • RealMedia • Smacker • RIFF • VOB • сравнение • сжатие |

| Аудио |

AIFF • APE • AU • DSD • DXD • MLP • MP3 • FLAC • SHN (англ.) WAV • WMA • сравнение • сжатие |

| Графические форматы (сжатие) | |

| Растровые |

Без потерь: BMP • FPX • GIF • ICO • ILBM • JBIG • PCX • PNG • PNM • PSD • RAW • TGA • WBMP • XCF • Включая сжатие с потерями: EXR • ICER • JBIG2 • JPEG / JP2 / JPEG-LS • JPEG XR (HD Photo) • PGF (англ.) • TIFF • WebP • Анимационные: APNG • GIF • MNG |

| Векторные |

AI • CDR • EMF • EPS • PS • SVG • WMF • XPS • Анимационные: SVG • SWF • 3D: 3DS • VRML • X3D |

| Комплексные |

CGM • DjVu • PDF |

Файл формата jpg: чем открыть, описание, особенности

JPG – часто используемый графический формат сжатого изображения, разработанный компанией Joint Photo.

JPG – часто используемый графический формат сжатого изображения, разработанный компанией Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG). Файлы имеют высокий уровень сжатия и поддерживают глубину цвета в 24 бит. Благодаря этим характеристикам файлы с расширениями JPG/JPEG применяются в цифровых фотоаппаратах, смартфонах, видеокамерах. Несмотря на распространенность формата, у некоторых пользователей возникает вопрос – чем открыть JPG? Рассмотрим различные варианты и возможные сложности.

Область применения и свойства формата jpg

Формат JPG чаще применяется для хранения, обработки и передачи картинок с цветовыми и контрастными переходами. Подходит для размещения в интернете. В смартфонах, цифровых фотоаппаратах и видеокамерах изображения хранятся в этом формате, это обусловлено минимальным заполнением объема памяти и качеством на выходе.

Положительные и отрицательные характеристики файла формата jpg

К плюсам формата относятся:

- Широкий диапазон уровня сжатия (качество и размер файла зависят от степени сжатия).

- Минимальный размер файла.

- Согласованность с браузерами и текстовыми редакторами.

- Отображение на современных устройствах.

- При невысоком уровне сжатия не страдает качество картинки.

Благодаря этим характеристикам, формат завоевал популярность, как у пользователей, так и у продвинутых программистов.

- При достаточном уровне сжатия может “развалиться” на блоки пикселей.

- Не поддерживает прозрачность.

- Не рекомендуется редактировать файл после восстановления. Каждая новая манипуляция снижает качество изображения.

Чем и как открывать файлы jpg

Изображения JPG используются повсеместно, поэтому программа для просмотра JPG входит в набор для стандартных опций Windows. В случае, если программа для просмотра фотографий JPG не встроена в операционную систему, файл можно открыть в Microsoft Paint, который есть в списке стандартных программ для Windows.

Открываем на компьютере

У рядового пользователя обычно не возникает проблем с вопросом, как открыть файл JPG на компьютере. Большое распространение получили программы для jpg/jpeg файлов. Вот некоторые из них:

Скачать программу для просмотра jpg можно в сети интернет, если она есть в свободном доступе, либо купить лицензионную версию у разработчика. Каждая из них имеет особенности работы с jpg/jpeg файлами.

Открыть формат через Windows 10

Программа для просмотра JPG для Windows 10 отсутствует в базовом ПО. Однако в случае смены ОС с Windows 7 или 8.1, средство просмотра фотографий может присутствовать на ПК. Существует способ удостовериться, что программы для открытия jpg файлов установлены. Для этого кликните на изображение правой кнопкой мыши и найдите пункт «Открыть с помощью». Далее просмотрите список предложенных средств для просмотра.

Воспользуйтесь программой для открытия JPG WinAero Tweaker. После запуска утилиты, перейдите в раздел «Windows Accessories» и выберите пункт «Activate Windows Photo Viewer».

Просмотреть с помощью Windows 7

В Windows 7 сразу установлено ПО, которое открывает разноформатные файлы, в том числе и JPG. Если же установлено больше 2-х программ для просмотра и открытия файлов JPG, при двойном щелчке мышки на изображении, откроется программа, установленная по умолчанию. Чтобы открыть формат JPG другой программой из меню «Проводника», выбрать и нажать на кнопку «Открыть с помощью. ».

Онлайн-просмотр

Открыть файл JPG онлайн и просмотреть фото можно популярными программами:

Как открыть поврежденный файл jpg?

Как определить, что файл JPG поврежден? При попытке запуска появляется ошибка (диалоговое окно с сообщением «файл поврежден») или же не открывается вовсе. Тогда используют программы RS File Repair, PixRecovery, JPEGfix для восстановления файлов. Большинство таких программ можно бесплатно скачать в интернете.

Источник статьи: http://freesoft.ru/blog/fayl-formata-jpg-chem-otkryt-opisanie-osobennosti

Как в Windows открывать и редактировать файлы формата JPG или JPEG

Файл с расширением JPG или JPEG является файлом изображения. Причина, по которой некоторые файлы JPEG-изображений используют JPG-расширение, а другие – JPEG, объясняется ниже, но независимо от расширения, оба файла имеют один формат.

JPG файлы широко используются, потому что их алгоритм сжатия значительно уменьшает размер файла, что делает его идеальным для совместного использования, хранения и отображения на веб-сайтах. Однако, это сжатие JPEG также снижает качество изображения, что может быть заметно, если оно сильно сжато.

Некоторые файлы JPEG-изображений используют .Jpe расширение, но это не очень распространено. JFIF – это файлы формата обмена файлами JPEG, которые также используют сжатие JPEG, но не так популярны, как файлы JPG.

Как открыть файл JPG/JPEG

JPG-файлы поддерживаются всеми просмотрщиками и редакторами изображений. Это самый распространенный формат изображения.

Вы можете открыть файлы JPG с помощью веб-браузера, например Chrome или Edge (перетащите локальные файлы JPG в окно браузера) или встроенные программы Microsoft, такие как Paint, Microsoft Windows Photos и Microsoft Windows Photo Viewer. Если вы находитесь на компьютере Mac, Apple Preview и Apple Photos могут открыть файл JPG.

Adobe Photoshop, GIMP и практически любая другая программа, которая просматривает изображения, в том числе онлайн-сервисы, такие как Google Drive, также поддерживают JPG-файлы.

Мобильные устройства также поддерживают открытие файлов JPG, что означает, что вы можете просматривать их в своей электронной почте и через текстовые сообщения без необходимости устанавливать дополнительное приложение для просмотра JPG.

Некоторые программы не распознают изображение как файл JPEG Image, если только оно не имеет соответствующего расширения файла, который ищет программа. Например, некоторые редакторы изображений и средства просмотра будут открывать только .JPG файлы и не поймут, что .JPEG – то же самое. В этих случаях вы можете просто переименовать файл, чтобы получить расширение файла, которое понимает программа.

Некоторые форматы файлов используют расширения файлов, которые выглядят как .JPG файлы, но на самом деле не связаны. Примеры включают JPR (JBuilder Project или Fugawi Projection), JPS (Stereo JPEG Image или Akeeba Backup Archive) и JPGW (JPEG World).

Как конвертировать файл JPG / JPEG

Существует два основных способа конвертировать файлы JPG. Вы можете использовать вьювер/редактор изображений, чтобы сохранить его в новом формате (при условии, что функция поддерживается) или добавить файл JPG в программу преобразования изображений.

Например, FileZigZag является онлайн конвертером JPG, который может сохранить файл в ряде других форматов, включая PNG, TIF / TIFF, GIF, BMP, DPX, TGA, PCX и YUV.

Вы даже можете конвертировать файлы JPG в формат MS Word, такой как DOCX или DOC с Zamzar, который похож на FileZigZag в том, что он преобразует файл JPG в режиме онлайн. Он также сохраняет JPG в ICO, PS, PDF и WEBP, среди других форматов.

Если вы просто хотите вставить файл JPG в документ Word, вам не нужно конвертировать файл в формат MS Word. Вместо этого используйте встроенное меню Word: Вставить → Картинка, чтобы подключить JPG непосредственно к документу, даже если у вас уже есть текст.

Откройте файл JPG в Microsoft Paint и используйте меню Файл → Сохранить как, чтобы преобразовать его в BMP, DIB, PNG, TIFF и т.д. Другие средства просмотра и редакторы JPG, упомянутые выше, поддерживают аналогичные параметры меню и форматы выходных файлов.

Использование веб-сервиса Convertio является одним из способов преобразования JPG в EPS, если вы хотите, чтобы файл изображения был в этом формате. Если это не работает, вы можете попробовать AConvert.com.

Несмотря на название, веб-сайт Online PNG to SVG Converter также умеет преобразовывать файлы JPG в формат изображения SVG (vector).

Если у вас есть файл PDF и вы хотите сделать из него JPG/JPEG, попробуйте PDF.io

Чем отличается JPG от JPEG

Интересно, какая разница между JPEG и JPG? Форматы файлов идентичны, но в одном из расширений есть дополнительная буква. На самом деле. это единственная разница.

JPG и JPEG представляют собой формат изображения, поддерживаемый совместной группой экспертов по фотографии, и имеют одинаковое значение. Причина различных расширений файлов связана с ранними версиями Windows, не принимавших «длинное» расширение.

Ситуация похожа на HTM и HTML, когда формат JPEG был впервые введен, официальным расширением файла был JPEG (с четырьмя буквами). Однако, Windows в то время требовала, чтобы все расширения файлов не превышали трёх букв, вот почему .JPG использовался для того же самого формата. Компьютеры Mac, однако, уже тогда не имели такого ограничения.

Произошло то, что оба расширения файлов использовались в обеих системах, а затем Windows изменила свои требования, чтобы принять более длинные расширения файлов, но JPG всё ещё используется. Поэтому файлы JPG и JPEG распространяются и продолжают создаваться.

В то время как оба расширения файлов существуют, форматы точно такие же, и любой из них может быть переименован в другой без потери качества и функциональности.

Источник статьи: http://windows-school.ru/blog/fajly_formata_jpg/2019-05-14-391

A photo of a European wildcat with the compression rate decreasing and hence quality increasing, from left to right |

|

| Filename extension |

|

|---|---|

| Internet media type |

image/jpeg |

| Type code | JPEG |

| Uniform Type Identifier (UTI) | public.jpeg |

| Magic number | ff d8 ff |

| Developed by | Joint Photographic Experts Group, IBM, Mitsubishi Electric, AT&T, Canon Inc.[1] |

| Initial release | September 18, 1992; 30 years ago |

| Type of format | Lossy image compression format |

| Extended to | JPEG 2000 |

| Standard | ISO/IEC 10918, ITU-T T.81, ITU-T T.83, ITU-T T.84, ITU-T T.86 |

| Website | jpeg.org/jpeg/ |

Continuously varied JPEG compression (between Q=100 and Q=1) for an abdominal CT scan

JPEG ( JAY-peg)[2] is a commonly used method of lossy compression for digital images, particularly for those images produced by digital photography. The degree of compression can be adjusted, allowing a selectable tradeoff between storage size and image quality. JPEG typically achieves 10:1 compression with little perceptible loss in image quality.[3] Since its introduction in 1992, JPEG has been the most widely used image compression standard in the world,[4][5] and the most widely used digital image format, with several billion JPEG images produced every day as of 2015.[6]

The term «JPEG» is an acronym for the Joint Photographic Experts Group, which created the standard in 1992.[7] JPEG was largely responsible for the proliferation of digital images and digital photos across the Internet and later social media.[8]

JPEG compression is used in a number of image file formats. JPEG/Exif is the most common image format used by digital cameras and other photographic image capture devices; along with JPEG/JFIF, it is the most common format for storing and transmitting photographic images on the World Wide Web.[9] These format variations are often not distinguished and are simply called JPEG.

The MIME media type for JPEG is «image/jpeg,» except in older Internet Explorer versions, which provide a MIME type of «image/pjpeg» when uploading JPEG images.[10] JPEG files usually have a filename extension of «jpg» or «jpeg.» JPEG/JFIF supports a maximum image size of 65,535×65,535 pixels,[11] hence up to 4 gigapixels for an aspect ratio of 1:1. In 2000, the JPEG group introduced a format intended to be a successor, JPEG 2000, but it was unable to replace the original JPEG as the dominant image standard.[12]

History[edit]

Background[edit]

The original JPEG specification published in 1992 implements processes from various earlier research papers and patents cited by the CCITT (now ITU-T) and Joint Photographic Experts Group.[1]

The JPEG specification cites patents from several companies. The following patents provided the basis for its arithmetic coding algorithm.[1]

- IBM

- U.S. Patent 4,652,856 – February 4, 1986 – Kottappuram M. A. Mohiuddin and Jorma J. Rissanen – Multiplication-free multi-alphabet arithmetic code

- U.S. Patent 4,905,297 – February 27, 1990 – G. Langdon, J.L. Mitchell, W.B. Pennebaker, and Jorma J. Rissanen – Arithmetic coding encoder and decoder system

- U.S. Patent 4,935,882 – June 19, 1990 – W.B. Pennebaker and J.L. Mitchell – Probability adaptation for arithmetic coders

- Mitsubishi Electric

- JP H02202267 (1021672) – January 21, 1989 – Toshihiro Kimura, Shigenori Kino, Fumitaka Ono, Masayuki Yoshida – Coding system

- JP H03247123 (2-46275) – February 26, 1990 – Fumitaka Ono, Tomohiro Kimura, Masayuki Yoshida, and Shigenori Kino – Coding apparatus and coding method

The JPEG specification also cites three other patents from IBM. Other companies cited as patent holders include AT&T (two patents) and Canon Inc.[1] Absent from the list is U.S. Patent 4,698,672, filed by Compression Labs’ Wen-Hsiung Chen and Daniel J. Klenke in October 1986. The patent describes a DCT-based image compression algorithm, and would later be a cause of controversy in 2002 (see Patent controversy below).[13] However, the JPEG specification did cite two earlier research papers by Wen-Hsiung Chen, published in 1977 and 1984.[1]

JPEG standard[edit]

«JPEG» stands for Joint Photographic Experts Group, the name of the committee that created the JPEG standard and also other still picture coding standards. The «Joint» stood for ISO TC97 WG8 and CCITT SGVIII. Founded in 1986, the group developed the JPEG standard during the late 1980s. The group published the JPEG standard in 1992.[4]

In 1987, ISO TC 97 became ISO/IEC JTC 1 and, in 1992, CCITT became ITU-T. Currently on the JTC1 side, JPEG is one of two sub-groups of ISO/IEC Joint Technical Committee 1, Subcommittee 29, Working Group 1 (ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 29/WG 1) – titled as Coding of still pictures.[14][15][16] On the ITU-T side, ITU-T SG16 is the respective body. The original JPEG Group was organized in 1986,[17] issuing the first JPEG standard in 1992, which was approved in September 1992 as ITU-T Recommendation T.81[18] and, in 1994, as ISO/IEC 10918-1.

The JPEG standard specifies the codec, which defines how an image is compressed into a stream of bytes and decompressed back into an image, but not the file format used to contain that stream.[19]

The Exif and JFIF standards define the commonly used file formats for interchange of JPEG-compressed images.

JPEG standards are formally named as Information technology – Digital compression and coding of continuous-tone still images. ISO/IEC 10918 consists of the following parts:

| Part | ISO/IEC standard | ITU-T Rec. | First public release date | Latest amendment | Title | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part 1 | ISO/IEC 10918-1:1994 | T.81 (09/92) | Sep 18, 1992 | Requirements and guidelines | ||

| Part 2 | ISO/IEC 10918-2:1995 | T.83 (11/94) | Nov 11, 1994 | Compliance testing | Rules and checks for software conformance (to Part 1). | |

| Part 3 | ISO/IEC 10918-3:1997 | T.84 (07/96) | Jul 3, 1996 | Apr 1, 1999 | Extensions | Set of extensions to improve the Part 1, including the Still Picture Interchange File Format (SPIFF).[21] |

| Part 4 | ISO/IEC 10918-4:1999 | T.86 (06/98) | Jun 18, 1998 | Jun 29, 2012 | Registration of JPEG profiles, SPIFF profiles, SPIFF tags, SPIFF colour spaces, APPn markers, SPIFF compression types and Registration Authorities (REGAUT) | methods for registering some of the parameters used to extend JPEG |

| Part 5 | ISO/IEC 10918-5:2013 | T.871 (05/11) | May 14, 2011 | JPEG File Interchange Format (JFIF) | A popular format which has been the de facto file format for images encoded by the JPEG standard. In 2009, the JPEG Committee formally established an Ad Hoc Group to standardize JFIF as JPEG Part 5.[22] | |

| Part 6 | ISO/IEC 10918-6:2013 | T.872 (06/12) | Jun 2012 | Application to printing systems | Specifies a subset of features and application tools for the interchange of images encoded according to the ISO/IEC 10918-1 for printing. | |

| Part 7 | ISO/IEC 10918-7:2021 | T.873 (06/21) | May 2019 | June 2021 | Reference Software | Provides reference implementations of the JPEG core coding system |

Ecma International TR/98 specifies the JPEG File Interchange Format (JFIF); the first edition was published in June 2009.[23]

Patent controversy[edit]

In 2002, Forgent Networks asserted that it owned and would enforce patent rights on the JPEG technology, arising from a patent that had been filed on October 27, 1986, and granted on October 6, 1987: U.S. Patent 4,698,672 by Compression Labs’ Wen-Hsiung Chen and Daniel J. Klenke.[13][24] While Forgent did not own Compression Labs at the time, Chen later sold Compression Labs to Forgent, before Chen went on to work for Cisco. This led to Forgent acquiring ownership over the patent.[13] Forgent’s 2002 announcement created a furor reminiscent of Unisys’ attempts to assert its rights over the GIF image compression standard.

The JPEG committee investigated the patent claims in 2002 and were of the opinion that they were invalidated by prior art,[25] a view shared by various experts.[13][26]

Between 2002 and 2004, Forgent was able to obtain about US$105 million by licensing their patent to some 30 companies. In April 2004, Forgent sued 31 other companies to enforce further license payments. In July of the same year, a consortium of 21 large computer companies filed a countersuit, with the goal of invalidating the patent. In addition, Microsoft launched a separate lawsuit against Forgent in April 2005.[27] In February 2006, the United States Patent and Trademark Office agreed to re-examine Forgent’s JPEG patent at the request of the Public Patent Foundation.[28] On May 26, 2006, the USPTO found the patent invalid based on prior art. The USPTO also found that Forgent knew about the prior art, yet it intentionally avoided telling the Patent Office. This makes any appeal to reinstate the patent highly unlikely to succeed.[29]

Forgent also possesses a similar patent granted by the European Patent Office in 1994, though it is unclear how enforceable it is.[30]

As of October 27, 2006, the U.S. patent’s 20-year term appears to have expired, and in November 2006, Forgent agreed to abandon enforcement of patent claims against use of the JPEG standard.[31]

The JPEG committee has as one of its explicit goals that their standards (in particular their baseline methods) be implementable without payment of license fees, and they have secured appropriate license rights for their JPEG 2000 standard from over 20 large organizations.

Beginning in August 2007, another company, Global Patent Holdings, LLC claimed that its patent (U.S. Patent 5,253,341) issued in 1993, is infringed by the downloading of JPEG images on either a website or through e-mail. If not invalidated, this patent could apply to any website that displays JPEG images. The patent was under reexamination by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office from 2000 to 2007; in July 2007, the Patent Office revoked all of the original claims of the patent but found that an additional claim proposed by Global Patent Holdings (claim 17) was valid.[32] Global Patent Holdings then filed a number of lawsuits based on claim 17 of its patent.

In its first two lawsuits following the reexamination, both filed in Chicago, Illinois, Global Patent Holdings sued the Green Bay Packers, CDW, Motorola, Apple, Orbitz, Officemax, Caterpillar, Kraft and Peapod as defendants. A third lawsuit was filed on December 5, 2007, in South Florida against ADT Security Services, AutoNation, Florida Crystals Corp., HearUSA, MovieTickets.com, Ocwen Financial Corp. and Tire Kingdom, and a fourth lawsuit on January 8, 2008, in South Florida against the Boca Raton Resort & Club. A fifth lawsuit was filed against Global Patent Holdings in Nevada. That lawsuit was filed by Zappos.com, Inc., which was allegedly threatened by Global Patent Holdings, and sought a judicial declaration that the ‘341 patent is invalid and not infringed.

Global Patent Holdings had also used the ‘341 patent to sue or threaten outspoken critics of broad software patents, including Gregory Aharonian[33] and the anonymous operator of a website blog known as the «Patent Troll Tracker.»[34] On December 21, 2007, patent lawyer Vernon Francissen of Chicago asked the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to reexamine the sole remaining claim of the ‘341 patent on the basis of new prior art.[35]

On March 5, 2008, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office agreed to reexamine the ‘341 patent, finding that the new prior art raised substantial new questions regarding the patent’s validity.[36] In light of the reexamination, the accused infringers in four of the five pending lawsuits have filed motions to suspend (stay) their cases until completion of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office’s review of the ‘341 patent. On April 23, 2008, a judge presiding over the two lawsuits in Chicago, Illinois granted the motions in those cases.[37] On July 22, 2008, the Patent Office issued the first «Office Action» of the second reexamination, finding the claim invalid based on nineteen separate grounds.[38] On Nov. 24, 2009, a Reexamination Certificate was issued cancelling all claims.

Beginning in 2011 and continuing as of early 2013, an entity known as Princeton Digital Image Corporation,[39] based in Eastern Texas, began suing large numbers of companies for alleged infringement of U.S. Patent 4,813,056. Princeton claims that the JPEG image compression standard infringes the ‘056 patent and has sued large numbers of websites, retailers, camera and device manufacturers and resellers. The patent was originally owned and assigned to General Electric. The patent expired in December 2007, but Princeton has sued large numbers of companies for «past infringement» of this patent. (Under U.S. patent laws, a patent owner can sue for «past infringement» up to six years before the filing of a lawsuit, so Princeton could theoretically have continued suing companies until December 2013.) As of March 2013, Princeton had suits pending in New York and Delaware against more than 55 companies. General Electric’s involvement in the suit is unknown, although court records indicate that it assigned the patent to Princeton in 2009 and retains certain rights in the patent.[40]

Typical use[edit]

The JPEG compression algorithm operates at its best on photographs and paintings of realistic scenes with smooth variations of tone and color. For web usage, where reducing the amount of data used for an image is important for responsive presentation, JPEG’s compression benefits make JPEG popular. JPEG/Exif is also the most common format saved by digital cameras.

However, JPEG is not well suited for line drawings and other textual or iconic graphics, where the sharp contrasts between adjacent pixels can cause noticeable artifacts. Such images are better saved in a lossless graphics format such as TIFF, GIF, PNG, or a raw image format. The JPEG standard includes a lossless coding mode, but that mode is not supported in most products.

As the typical use of JPEG is a lossy compression method, which reduces the image fidelity, it is inappropriate for exact reproduction of imaging data (such as some scientific and medical imaging applications and certain technical image processing work).

JPEG is also not well suited to files that will undergo multiple edits, as some image quality is lost each time the image is recompressed, particularly if the image is cropped or shifted, or if encoding parameters are changed – see digital generation loss for details. To prevent image information loss during sequential and repetitive editing, the first edit can be saved in a lossless format, subsequently edited in that format, then finally published as JPEG for distribution.

JPEG compression[edit]