Слово «Молдова» — это современное название страны, которая официально называется Республика Молдова. Когда страна находилась в составе Союза Стран Социалистических Республик, то она имела название Молдавия.

Таким образом, писать правильно «Молдова». «Молдавия» — это устаревшее наименование, которое можно встретить в литературных произведениях до 1991 года.

Примеры предложений

Молдова — это страна, которая славится своими плодородными землями и винами.

По данным переписи 2014 года население Молдовы составляло две целых и девять десятых миллиона человек.

Пример из литературы

Первой страной моего путешествия была Молдова, в которой я впервые за долгое время хорошо выспался…

(«Путешествие», А. Н. Кузнецов)

Слово «Молдавия», вроде бы, переходит в разряд фонетических историзмов (не путать с неправильно написанными словами, это совсем другое языковое явление!). Допустим пока, что так и есть. Когда-то была Молдавия, потом самопереименовалась в Молдову, обычное дело.

Мы должны признать следующее:

1.В официальной документации нужно писать Молдова. Или Moldova, если в документации использован латинский алфавит.

2.А «Молдавия» — это традиционная русская транскрипция названия государства. Поэтому слово Молдавия по-прежнему существует, оно по-прежнему означает название страны Moldova. В неофициальных случаях такое написание допустимо. Так же, как и написание «Германия» или «Папуа Новая Гвинея», например.

Colin

Высший разум

(533582)

12 лет назад

По-молдавски (румынски) Молдова, по-русски — Молдавия!

Это не как Россия и Российская федерация.

Это, скорее, как Россия, Русь и Раша, Русланд, ля Рюсси

или Москва и Москоу, Москау, Москý…

Дмитрий ПогодинЗнаток (332)

7 лет назад

Я живу в Беларуси. Говорю на русском языке. Официальное название по-русски Республика Беларусь или Беларусь. В Молдове такая же ситуация.

cristina rusnacЗнаток (346)

4 года назад

Правильно

Молдова — когда речь идет о ныне существующей стране, то правильно будет «Молдова». После распада СССР страна получила название Республика Молдова, поэтому правильно писать и говорить именно так, особенно это касается официальных документов.

Столица Молдовы — город Кишинев

Молдова — государство в Юго-Восточной Европе

Я поеду в поездку по Молдове

Было правильно

Молдавия — название республики в составе бывшего СССР. Этот термин можно использовать только в контексте описания исторических событий.

Антон СлепцовУченик (216)

3 года назад

Не фига правильно модова так ка страна называеися республика молдова и по английс по русски по фрацузски раньше в ссср была молдавия

Виктор ЖмураПрофи (686)

1 год назад

«Молдова»-часть территории Румынии от р. Прут и до Карпатских гор… В Румынии еще есть области: Валахия, Мунтения, ну и т. п… Территория от р. Прут и до р. Днестр — Бессарабия !!!А от р. Днестр и на восток = Приднестровье (Транснистрия по-вашему). Приднестровье было передано Османской империей России в 1791 году в декабре по Ясскому мирному договору. Читайте документы.

Галина Аванесова

Высший разум

(196449)

12 лет назад

У нас двое пострадавших: Белоруссия и Молдавия. Остальные уцелели. Пока.

Вопрос № 221250

— Здравствуйте! Уже в четвертый раз отправляю эту просьбу помочь! Скажите, пожалуйста, как правильно сегодня пишется название Республики Беларусь: Белоруссия или Беларусь? Тот же вопрос и в отношении Молдавии-Молдовы, Киргизии-Кыргызстана, Туркмении-Туркменистана. Где найти правила по этому поводу? Очень прошу помочь разобраться.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка:

— См. в http://spravka.gramota.ru/offdocs.html?id=258 [Общероссийском классификаторе стран мира] .

_____

Вопрос № 218576

— Здравствуйте. Вопрос: в связи со сменой названий государств бывшего СССР изменилось ли название национальностей? Например: Кыргызстан — кыргыз (???), Молдова — молдованин (???). Моя работа связана с переводом иностранных документов. В киргизском (или кыргызском??? ) паспорте на странице, заполенной на руском языке, в графе «национальность» пишется «кыргыз». А недавно дама настаивала, чтобы в переводе ее молдавского паспорта было написано «молдованка», так как государство назывется Молдова. В словарях, к которым я обращалась, такие слова еще не зафикированы. Заранее спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка:

— По-русски правильно: _киргиз, молдаванин, молдаванка, киргизский_. Такое написание зафиксировано в словарях русского языка, этими рекомендациями и следует руководствоваться.

http://www.gramota.ru/spravka/buro/search_answer/?s=кыргызстан

Вопрос № 209079

— Скажите, пожалуйста, как правильно называть в нашей литературе государство Молдова или Молдавия. Спасибо.

Ответ справочной службы русского языка:

_Республика Молдова_ — официальное название, в остальных случаях возможно использование названия _Молдавия_.

http://www.gramota.ru/spravka/buro/search_answer/?s=молдова+или+молдавия

_____

УАУ!! !

… Молдавия – это бывшая Бессарабия и Молдавская ССР в составе Союза ССР. Молдова – одна из восточных областей современной Румынии (бывшей Валахии — Мунтении)…

http://www.familii.ru/index.php?pCode=news&news=484

Олег

Ученик

(177)

6 лет назад

В древних картах, когда ещё не было Румынии, а была Валахия, но уже было княжество Молдавское во главе с Штефаном великим, и написано там Moldavie или Moldavia.

Артем АрнаковЗнаток (369)

2 года назад

В древних картах было такое государство как Московия, значит и называть правильно нужно не Российская Федерация, а Московия. Давайте жить по древним картам

С распадом СССР вместо одного названия страны мы получили 15 независимых стран, со своими отличными от названия республик, названиями. Необходимо понимать как правильно употреблять эти слова в письменной и устной речи.

1. Молдавия

С 1924 года была автономной, а в 1940 году вошла в состав СССР, как самостоятельная Молдавская Советская Социалистическая Республика. Тогда она называлась на русском языке Молдавия, а ее граждане молдаване, язык жителей-молдавский.

2. Молдова

С 1991 года было образовано независимое государство, получившее название Республика Молдова. Исторически, данная территория была названа по имени реки Молдова ( почему реку так назвали-отдельная, очень занимательная история), поэтому граждане этого небольшого государства и решили вернуться к истокам. Обращаясь к Общероссийскому классификатору стран мира, как к компетентному источнику, мы видим, что официальное название данной страны-Республика Молдова.

Подводя итоги, можно сказать, что слова являются абсолютными синонимами. Если вы упоминаете название государства в официальных документах, то обязательно употребление слова «Молдова». Но если вы просто говорите о стране, то вполне допустимо употребление слова «Молдавия».

Правильно

Молдова — когда речь идет о ныне существующей стране, то правильно будет «Молдова». После распада СССР страна получила название Республика Молдова, поэтому правильно писать и говорить именно так. Особенно это касается официальных документов.

Столица Молдовы — город Кишинев.

Молдова — государство в Юго-Восточной Европе.

Я собираюсь в поездку по Молдове.

Было правильно

Молдавия — название республики в составе бывшего СССР. Это слово можно использовать только в контексте описания исторических событий.

Если вы нашли ошибку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите левый Ctrl+Enter.

This article is about the modern state. For the historical principality, see Moldavia. For other uses, see Moldova (disambiguation).

Coordinates: 47°N 29°E / 47°N 29°E

|

Republic of Moldova Republica Moldova (Romanian) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Coat of arms |

|

| Anthem: Limba noastră «Our language» |

|

Location of Moldova in Europe (green) |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Chișinău 47°0′N 28°55′E / 47.000°N 28.917°E |

| Official language and national language |

Romanian (officially Moldovan) |

| Recognised minority languages[1][2][3] |

See here

|

| Ethnic groups

(2014; excl. Transnistria)[4] |

82.07% Moldovans/Romanians[a] 6.57% Ukrainians 4.57% Gagauzes 4.06% Russians 1.88% Bulgarians 0.85% Other |

| Religion

(2014; excl. Transnistria)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Moldovan |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

|

• President |

Maia Sandu |

|

• Prime Minister |

Dorin Recean |

|

• President of the Parliament |

Igor Grosu |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Formation | |

|

• Principality of Moldavia |

1346 |

|

• Bessarabia Governorate |

1812 |

|

• Moldavian Democratic Republic |

15 December 1917 |

|

• Union with Romania |

9 April 1918 |

|

• Moldavian ASSR |

12 October 1924 |

|

• Moldavian SSR |

2 August 1940 |

|

• Transnistria War |

2 November 1990 |

|

• Independence from the Soviet Union |

27 August 1991a |

|

• Constitution adopted |

29 July 1994 |

| Area | |

|

• Incl. Transnistria |

33,851[5] km2 (13,070 sq mi) (135th) |

|

• Water (%) |

1.4 (incl. Transnistria) |

|

• Excl. Transnistria |

30,334 km2 (11,712 sq mi) [b] |

| Population | |

|

• January 2022 estimate |

2,603,813[7][c] (139th) |

|

• 2014 census |

2,804,801[4][c] |

|

• Density |

85.8/km2 (222.2/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2019) | low |

| HDI (2021) | high · 80th |

| Currency | Moldovan leu (MDL) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

|

• Summer (DST) |

UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +373 |

| ISO 3166 code | MD |

| Internet TLD | .md |

|

Website |

|

|

Moldova ( mol-DOH-və, sometimes MOL-də-və;[11][12][13] Romanian pronunciation: [molˈdova]), officially the Republic of Moldova (Romanian: Republica Moldova), is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe.[14] It is bordered by Romania to the west and Ukraine to the north, east, and south.[15] The unrecognised state of Transnistria lies across the Dniester river on the country’s eastern border with Ukraine. Moldova’s capital and largest city is Chișinău.

Most of Moldovan territory was a part of the Principality of Moldavia from the 14th century until 1812, when it was ceded to the Russian Empire by the Ottoman Empire (to which Moldavia was a vassal state) and became known as Bessarabia. In 1856, southern Bessarabia was returned to Moldavia, which three years later united with Wallachia to form Romania, but Russian rule was restored over the whole of the region in 1878. During the 1917 Russian Revolution, Bessarabia briefly became an autonomous state within the Russian Republic. In February 1918, it declared independence and then integrated into Romania later that year following a vote of its assembly. The decision was disputed by Soviet Russia, which in 1924 established, within the Ukrainian SSR, a so-called Moldavian autonomous republic on partially Moldovan-inhabited territories to the east of Bessarabia.

In 1940, as a consequence of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Romania was compelled to cede Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina to the Soviet Union, leading to the creation of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavian SSR). On 27 August 1991, as the dissolution of the Soviet Union was underway, the Moldavian SSR declared independence and took the name Moldova.[16] However, the strip of Moldovan territory on the east bank of the Dniester has been under the de facto control of the breakaway government of Transnistria since 1990. The constitution of Moldova was adopted in 1994, and the country became a parliamentary republic with a president as head of state and a prime minister as head of government.

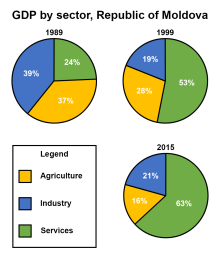

Moldova is the second poorest country in Europe by GDP per official capita after Ukraine and much of its GDP is dominated by the service sector.[17] It has one of the lowest Human Development Indexes in Europe, ranking 76th in the world (2022).[10] Moldova is a member state of the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the World Trade Organization, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the GUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development, the Commonwealth of Independent States, the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation, and the Association Trio. Moldova has been an official candidate for membership in the European Union since June 2022.[18]

Etymology[edit]

The name Moldova is derived from the Moldova River (German: Moldau); the valley of this river served as a political centre at the time of the foundation of the Principality of Moldavia in 1359.[19] The origin of the name of the river remains unclear. According to a legend recounted by Moldavian chroniclers Dimitrie Cantemir and Grigore Ureche, Prince Dragoș named the river after hunting aurochs: following the chase, the prince’s exhausted hound Molda (Seva) was drowned in the river. The dog’s name, given to the river, extended to the principality.[20]

For a short time in the 1990s, at the founding of the Commonwealth of Independent States, the name of the current Republic of Moldova was also spelled Moldavia.[21] After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country began to use the Romanian name, Moldova. Officially, the name Republic of Moldova is designated by the United Nations.

History[edit]

Prehistory[edit]

The prehistory of Moldova covers the period from the Upper Paleolithic which begins with the presence of Homo sapiens in the area of Southeastern Europe some 44,000 years ago and extends into the appearance of the first written records in Classical Antiquity in Greece. In 2010, Oldowan flint tools were discovered at Bayraki that are 800,000–1.2 million years old.[22] During the Neolithic Age, Moldova’s territory stood at the centre of the large Cucuteni–Trypillia culture that stretched east beyond the Dniester River in Ukraine and west up to and beyond the Carpathian Mountains in Romania. The people of this civilization, which lasted roughly from 5500 to 2750 BC, practised agriculture, raised livestock, hunted, and made intricately designed pottery.[23]

Antiquity and the early Middle Ages[edit]

This area of present-day Moldova was inhabited by ancient Dacians and Moldovans identify themselves with their ancestors. Carpian tribes also inhabited Moldova’s territory in the period of classical antiquity. Between the first and seventh centuries AD, the south came intermittently under the control of the Roman and then the Byzantine Empires. Due to its strategic location on a route between Asia and Europe, the territory of modern Moldova experienced many invasions in late antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, notably by Goths, Huns, Avars, Bulgars, Magyars, Pechenegs, Cumans, Mongols and Tatars.

In the 11th century, a Viking by the name of Rodfos was possibly killed in the area by the Blakumen who betrayed him.[24] In 1164, the future Byzantine emperor Andronikos I Komnenos, while attempting to reach the Principality of Halych, was taken prisoner by Vlachs, possibly in the area which now constitutes Moldova.

The East Slavic Hypatian Chronicle (13th century) mentions the Bolohoveni people, who resided on the eastern fringes of Moldovan territory and in the Rus’ principalities of Halych, Volhynia and Kyiv; their ethnic origin is disputed by historians. Archaeological research has identified the location of 13th-century fortified settlements in this region.[25] The Bolohoveni disappeared from written chronicles after they were defeated in 1257 by Daniel of Galicia. In the early 13th century, the Brodniks, a possible Slavic–Vlach vassal tribe of Halych, were also present in much of the region’s territory.

Founding of the Principality of Moldavia[edit]

The Principality of Moldavia began when a Vlach voivode (military leader), Dragoș, arrived in the region of the Moldova River. His people from the voivodeship at Maramureș soon followed. Dragoș established a polity as a vassal to the Kingdom of Hungary in the 1350s. The independence of the Principality of Moldavia came when Bogdan I, another Vlach voivode from Maramureș who had fallen out with the Hungarian king, crossed the Carpathian mountains in 1359 and took control of Moldavia, wresting the region from Hungary. The Principality of Moldavia was bounded by the Carpathian Mountains in the west, the Dniester River in the east, and the Danube River and Black Sea to the south. Its territory comprised the present-day territory of the Republic of Moldova, the eastern eight counties of Romania, and parts of the Chernivtsi Oblast and Budjak region of present-day Ukraine. Locals referred to the principality as Moldova — like the present-day republic and Romania’s north-eastern region.

Between Poland and Hungary[edit]

The history of what is today Moldova has been intertwined with that of Poland for centuries. The Polish chronicler Jan Długosz mentioned Moldavians as having joined a military expedition in 1342, under King Ladislaus I, against the Margraviate of Brandenburg.[26] The Polish state was powerful enough to counter the Hungarian Kingdom which was consistently interested in bringing the area that would become Moldavia into its political orbit.

Ties between Poland and Moldavia expanded after the founding of the Moldavian state by Bogdan of Cuhea, a Vlach voivode from Maramureș who had fallen out with the Hungarian king. Crossing the Carpathian mountains in 1359, the voivode took control of Moldavia and succeeded in creating Moldavia as an independent political entity. Despite being disfavored by the brief union of Angevin Poland and Hungary (the latter was still the country’s overlord), Bogdan’s successor Lațcu, the Moldavian ruler also likely allied himself with the Poles. Lațcu also accepted conversion to Roman Catholicism around 1370, but his gesture was to remain without consequences.

Polish influence grows[edit]

Petru I profited from the end of the Polish-Hungarian union and moved the country closer to the Jagiellon realm, becoming a vassal of king Jogaila of Poland on 26 September 1387. This gesture was to have unexpected consequences: Petru supplied the Polish ruler with funds needed in the war against the Teutonic Knights, and was granted control over Pokuttya until the debt was to be repaid; as this is not recorded to have been carried out, the region became disputed by the two states, until it was lost by Moldavia in the Battle of Obertyn (1531). Prince Petru also expanded his rule southwards to the Danube Delta. His brother Roman I conquered the Hungarian-ruled Cetatea Albă in 1392, giving Moldavia an outlet to the Black Sea, before being toppled from the throne for supporting Fyodor Koriatovych in his conflict with Vytautas the Great of Lithuania. Under Stephen I, growing Polish influence was challenged by Sigismund of Hungary, whose expedition was defeated at Ghindăoani in 1385; however, Stephen disappeared in mysterious circumstances.

Although Alexander I was brought to the throne in 1400 by the Hungarians (with assistance from Mircea I of Wallachia), this ruler shifted his allegiances towards Poland (notably engaging Moldavian forces on the Polish side in the Battle of Grunwald and the siege of Marienburg), and placed his own choice of rulers in Wallachia. His reign was one of the most successful in Moldavia’s history.

Increasing Ottoman influence[edit]

Administrative map of the Principality of Moldavia in 1483, with surrounding states

For all of his success, it was under the reign of Alexander I that the first confrontation with the Ottoman Turks took place at Cetatea Albă in 1420. A deep crisis was to follow Alexander l’s long reign, with his successors battling each other in a succession of wars that divided the country until the murder of Bogdan II and the accession of Peter Aaron in 1451. Nevertheless, Moldavia was subject to further Hungarian interventions after that moment, as Matthias Corvinus deposed Aaron and backed Alexăndrel to the throne in Suceava. Peter Aaron’s rule also signified the beginning of Moldavia’s Ottoman Empire allegiance, as the ruler was the first to agree to pay tribute to Sultan Mehmed II.

Moldavia at its apogee[edit]

Peter Aaron was eventually ousted by his nephew, Stephen the Great who would become the most important medieval Moldavian ruler who managed to uphold Moldavia’s autonomy against Hungary, Poland and the Ottoman Empire.[28][29] Under his rule, which lasted 47 years, Moldavia experienced a glorious political and cultural period.[30]

Age of Invasions[edit]

During this time, Moldavia was invaded repeatedly by Crimean Tatars and, beginning in the 15th century, by the Ottoman Turks. In 1538, the principality became a tributary to the Ottoman Empire, but it retained internal and partial external autonomy.[31] Nonetheless, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth continued to strongly influence Moldavia both through national politics as well as on the local level through significant intermarriage between Moldavian nobility and the Polish szlachta. When in May 1600, Michael the Brave removed Ieremia Movilă from Moldavia’s throne by winning the battle of Bacău, briefly reuniting under his rule Moldavia, Wallachia, and Transylvania, a Polish army led by Jan Zamoyski drove the Wallachians from Moldavia. Zamoyski reinstalled Ieremia Movilă to the throne, who put the country under the vassalage of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Moldavia finally returned to Ottoman vassalage in 1621.

Transnistria[edit]

While the region of Transnistria was never politically part of the Principality of Moldavia, there were sizable areas which were owned by Moldavian boyars or the Moldavian rulers. The earliest surviving deeds referring to lands beyond the Dniester river date from the 16th century.[32][full citation needed] Moldavian chronicler Grigore Ureche mentions that in 1584 some Moldavian villages from beyond the Dniester in the Kingdom of Poland were attacked and plundered by Cossacks.[33][non-primary source needed] Many Moldavians were members of Cossacks units, with two of them, Ioan Potcoavă and Dănilă Apostol becoming hetmans of Ukraine. Ruxandra Lupu, the daughter of Moldavian voivode Vasile Lupu who married Tymish Khmelnytsky, lived in Rașcov according to Ukrainian tradition.

While most of today’s Moldova came into the Ottoman orbit in the 16th century, a substantial part of Transnistria remained a part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth until the Second Partition of Poland in 1793.

Russian Empire[edit]

Territorial changes of Moldavia following the Treaty of Bucharest 1812.

In accordance with the Treaty of Bucharest of 1812, and despite numerous protests by Moldavian nobles on behalf of the sovereignty of their principality, the Ottoman Empire (of which Moldavia was a vassal) ceded to the Russian Empire the eastern half of the territory of the Principality of Moldavia along with Khotyn and old Bessarabia (modern Budjak), which Russia had already conquered and annexed. The new Russian province was called Oblast of Moldavia and Bessarabia, and initially enjoyed a large degree of autonomy. After 1828 this autonomy was progressively restricted and in 1871 the Oblast was transformed into the Bessarabia Governorate, in a process of state-imposed assimilation, Russification. As part of this process, the Tsarist administration in Bessarabia gradually removed the Moldavian language from official and religious use.[34]

Union with Romania and the return of the Russians[edit]

The Treaty of Paris (1856) returned the southern part of Bessarabia (later organised as the Cahul, Bolgrad and Ismail counties) to Moldavia, which remained an autonomous principality and, in 1859, united with Wallachia to form Romania. In 1878, as a result of the Treaty of Berlin, Romania was forced to cede the three counties back to the Russian Empire.

A multiethnic colonization[edit]

Over the 19th century, the Russian authorities encouraged the colonization of Bessarabia or parts of it by Russians, Ukrainians, Germans, Bulgarians, Poles, and Gagauzes, primarily in the northern and southern areas vacated by Turks and Nogais, the latter having been expelled in the 1770s and 1780s, during the Russo-Turkish Wars;[35][36][37][38] the inclusion of the province in the Pale of Settlement also allowed the immigration of more Bessarabian Jews.[d] The Moldavian proportion of the population decreased from an estimated 86% in 1816,[40] to around 52% in 1905.[41] During this time there were anti-Semitic riots, leading to an exodus of thousands of Jews to the United States.[42]

Russian Revolution[edit]

World War I brought in a rise in political and cultural (ethnic) awareness among the inhabitants of the region, as 300,000 Bessarabians were drafted into the Russian Army formed in 1917; within bigger units several «Moldavian Soldiers’ Committees» were formed. Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, a Bessarabian parliament, Sfatul Țării (a National Council), was elected in October–November 1917 and opened on December 3 [O.S. 21 November] 1917. The Sfatul Țării proclaimed the Moldavian Democratic Republic (December 15 [O.S. 2 December] 1917) within a federal Russian state, and formed a government (21 December [O.S. 8 December] 1917).

Greater Romania[edit]

After the Romanian army occupied the region in early January 1918 at the request of the National Council, Bessarabia proclaimed independence from Russia on February 6 [O.S. 24 January] 1918 and requested the assistance of the French army present in Romania (general Henri Berthelot) and of the Romanian Army.[43] On April 9 [O.S. 27 March] 1918, the Sfatul Țării decided with 86 votes for, 3 against and 36 abstaining, to unite with the Kingdom of Romania. The union was conditional upon fulfilment of the agrarian reform, autonomy, and respect for universal human rights.[44] A part of the interim Parliament agreed to drop these conditions after Bukovina and Transylvania also joined the Kingdom of Romania, although historians note that they lacked the quorum to do so.[45][46][47][48][49]

This union was recognized by most of the principal Allied Powers in the 1920 Treaty of Paris, which however was not ratified by all of its signatories.[50][51] The newly Soviet Russia did not recognize Romanian rule over Bessarabia, considering it an occupation of Russian territory.[52] Uprisings against Romanian rule took place in 1919 at Khotyn and Bender, but were eventually suppressed by the Romanian Army.

In May 1919, the Bessarabian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed as a government in exile. After the failure of the Tatarbunary Uprising in 1924, the Moldavian Autonomous Region, created earlier in the Transnistria region, was elevated to an Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic within the Ukrainian SSR.

World War II and Soviet era[edit]

Annexation by the USSR[edit]

In August 1939, the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact and its secret additional protocol were signed, by which Nazi Germany recognized Bessarabia as being within the Soviet sphere of influence, which led the latter to actively revive its claim to the region.[53] On 28 June 1940, the Soviet Union issued an ultimatum to Romania requesting the cession of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, with which Romania complied the following day. Soon after, the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (Moldavian SSR, MSSR) was established,[53] comprising about 65% of Bessarabia, and 50% of the now-disbanded Moldavian ASSR (the present-day Transnistria). Ethnic Germans left in 1940.

Reincorporation into Romania and the Soviet occupation[edit]

As part of the 1941 Axis invasion of the Soviet Union, Romania regained the territories of Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina, and seized a territory which became known as Transnistria Governorate. Romanian forces, working with the Germans, deported or massacred about 300,000 Jews[citation needed], including 147,000 from Bessarabia and Bukovina. Of the latter, approximately 90,000 died.[54] Between 1941 and 1944 partisan detachments acted against the Romanian administration. The Soviet Army re-captured the region in February–August 1944, and re-established the Moldavian SSR. Between the end of the Second Jassy–Kishinev Offensive in August 1944 and the end of the war in May 1945, 256,800 inhabitants of the Moldavian SSR were drafted into the Soviet Army. 40,592 of them perished.[55]

During the periods 1940–1941 and 1944–1953, deportations of locals to the northern Urals, to Siberia, and northern Kazakhstan occurred regularly, with the largest ones on 12–13 June 1941, and 5–6 July 1949, accounting from MSSR alone for 18,392[e] and 35,796 deportees respectively.[56] Other forms of Soviet persecution of the population included political arrests or, in 8,360 cases, execution.

Moldova in the USSR after World War II[edit]

In 1946, as a result of a severe drought and excessive delivery quota obligations and requisitions imposed by the Soviet government, the southwestern part of the USSR suffered from a major famine.[57][58] In 1946–1947, at least 216,000 deaths and about 350,000 cases of dystrophy were accounted by historians in the Moldavian SSR alone.[56] Similar events occurred in the 1930s in the Moldavian ASSR.[56] In 1944–53, there were several anti-Soviet resistance groups in Moldova; however the NKVD and later MGB managed to eventually arrest, execute or deport their members.[56]

In the postwar period, the Soviet government organized the immigration of working age Russian speakers (mostly Russians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians), into the new Soviet republic, especially into urbanized areas, partly to compensate for the demographic loss caused by the war and the emigration of 1940 and 1944.[59] In the 1970s and 1980s, the Moldavian SSR received substantial allocations from the budget of the USSR to develop industrial and scientific facilities and housing. In 1971, the Council of Ministers of the USSR adopted a decision «About the measures for further development of the city of Kishinev» (modern Chișinău), that allotted more than one billion roubles (approximately 6.8 billion in 2018 US dollars) from the USSR budget for building projects.[60]

The Soviet government conducted a campaign to promote a Moldovan ethnic identity distinct from that of the Romanians, based on a theory developed during the existence of the Moldavian ASSR. Official Soviet policy asserted that the language spoken by Moldovans was distinct from the Romanian language (see Moldovenism). To distinguish the two, during the Soviet period, Moldovan was written in the Cyrillic alphabet, in contrast with Romanian, which since 1860 had been written in the Latin alphabet.

All independent organizations were severely reprimanded, with the National Patriotic Front leaders being sentenced in 1972 to long prison terms.[61] The Commission for the Study of the Communist Dictatorship in Moldova is assessing the activity of the communist totalitarian regime.

Glasnost and Perestroika[edit]

In the 1980s, amid political conditions created by glasnost and perestroika, a Democratic Movement of Moldova was formed, which in 1989 became known as the nationalist Popular Front of Moldova (FPM).[62][63] Along with several other Soviet republics, from 1988 onwards, Moldova started to move towards independence. On 27 August 1989, the FPM organized a mass demonstration in Chișinău that became known as the Grand National Assembly. The assembly pressured the authorities of the Moldavian SSR to adopt a language law on 31 August 1989 that proclaimed the Moldovan language written in the Latin script to be the state language of the MSSR. Its identity with the Romanian language was also established.[62][64] In 1989, as opposition to the Communist Party grew, there were major riots in November.

Independence and aftermath[edit]

The first democratic elections for the local parliament were held in February and March 1990. Mircea Snegur was elected as Speaker of the Parliament, and Mircea Druc as Prime Minister. On 23 June 1990, the Parliament adopted the Declaration of Sovereignty of the «Soviet Socialist Republic Moldova», which, among other things, stipulated the supremacy of Moldovan laws over those of the Soviet Union.[62] After the failure of the 1991 Soviet coup d’état attempt, Moldova declared its independence on 27 August 1991.

On 21 December of the same year, Moldova, along with most of the other Soviet republics, signed the constitutive act that formed the post-Soviet Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). Moldova received official recognition on 25 December. On 26 December 1991, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Declaring itself a neutral state, Moldova did not join the military branch of the CIS. Three months later, on 2 March 1992, the country gained formal recognition as an independent state at the United Nations. In 1994, Moldova became a member of NATO’s Partnership for Peace program, and a member of the Council of Europe on 29 June 1995.[62]

Transnistria breaks away (1990 to present)[edit]

In the region east of the Dniester river, Transnistria, which includes a large proportion of predominantly russophone East Slavs of Ukrainian (28%) and Russian (26%) descent (altogether 54% as of 1989), an independent Pridnestrovian Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic was proclaimed on 16 August 1990, with its capital in Tiraspol.[62] The motives behind this move were fear of the rise of nationalism in Moldova.[citation needed] In the winter of 1991–1992, clashes occurred between Transnistrian forces, supported by elements of the 14th Guards Army, and the Moldovan police. Between 2 March and 26 July 1992, the conflict escalated into a military engagement. It was a brief war between Moldovan and separatist Transnistrian forces, with Russia intervening militarily on Transnistria’s side. It ended with a ceasefire and the establishment of a security zone policed by a three-way peacekeeping force of Russian, Transnistrian, and Moldovan personnel.[65]

Market economy (1992)[edit]

On 2 January 1992, Moldova introduced a market economy, liberalizing prices, which resulted in rapid inflation. From 1992 to 2001, the country suffered a serious economic crisis, leaving most of the population below the poverty line. In 1993, the Government of Moldova introduced a new national currency, the Moldovan leu, to replace the temporary cupon. The economy of Moldova began to change in 2001; and until 2008, the country saw a steady annual growth between 5% and 10%. The early 2000s also saw a considerable growth of emigration of Moldovans looking for work (mostly illegally) in Russia (especially the Moscow region), Italy, Portugal, Spain, and other countries; remittances from Moldovans abroad account for almost 38% of Moldova’s GDP, the second-highest percentage in the world, after Tajikistan (45%).[66][67]

Elections: 1994-2009[edit]

In the 1994 parliamentary elections, the Democratic Agrarian Party gained a majority of the seats, setting a turning point in Moldovan politics. With the nationalist Popular Front now in a parliamentary minority, new measures aiming to moderate the ethnic tensions in the country could be adopted. Plans for a union with Romania were abandoned,[62] and the new Constitution gave autonomy to the breakaway Transnistria and Gagauzia. On 23 December 1994, the Parliament of Moldova adopted a «Law on the Special Legal Status of Gagauzia», and in 1995, the latter was constituted.

After winning the 1996 presidential elections, on 15 January 1997, Petru Lucinschi, the former First Secretary of the Moldavian Communist Party in 1989–91, became the country’s second president (1997–2001), succeeding Mircea Snegur (1991–1996). In 2000, the Constitution was amended, transforming Moldova into a parliamentary republic, with the president being chosen through indirect election rather than direct popular vote.

Winning 49.9% of the vote, the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova (reinstituted in 1993 after being outlawed in 1991), gained 71 of the 101 MPs, and on 4 April 2001, elected Vladimir Voronin as the country’s third president (re-elected in 2005). The country became the first post-Soviet state where a non-reformed Communist Party returned to power.[62] New governments were formed by Vasile Tarlev (19 April 2001 – 31 March 2008), and Zinaida Greceanîi (31 March 2008 – 14 September 2009). In 2001–2003, relations between Moldova and Russia improved, but then temporarily deteriorated in 2003–2006, in the wake of the failure of the Kozak memorandum, culminating in the 2006 wine exports crisis. The Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova managed to stay in power for eight years.

In the April 2009 parliamentary elections, the Communist Party won 49.48% of the votes, followed by the Liberal Party with 13.14% of the votes, the Liberal Democratic Party with 12.43%, and the Alliance «Moldova Noastră» with 9.77%. The controversial results of this election sparked the April 2009 Moldovan parliamentary election protests.[68][69][70]

Stalemate 2009-2012[edit]

In August 2009, four Moldovan parties (Liberal Democratic Party, Liberal Party, Democratic Party, and Our Moldova Alliance) agreed to create the Alliance For European Integration that pushed the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova into opposition. On 28 August 2009, this coalition chose a new parliament speaker (Mihai Ghimpu) in a vote that was boycotted by Communist legislators. Vladimir Voronin, who had been President of Moldova since 2001, eventually resigned on 11 September 2009, but the Parliament failed to elect a new president. The acting president Mihai Ghimpu instituted the Commission for constitutional reform in Moldova to adopt a new version of the Constitution of Moldova. After the constitutional referendum aimed to approve the reform failed in September 2010,[71] the parliament was dissolved again and a new parliamentary election was scheduled for 28 November 2010.[72] On 30 December 2010, Marian Lupu was elected as the Speaker of the Parliament and the acting President of the Republic of Moldova.[73] In March 2012, Nicolae Timofti was elected as president of Moldova in a parliamentary vote, becoming the first full-time president since Vladimir Voronin, a Communist, resigned in September 2009. Before the election of Timofti, Moldova had had three acting presidents in three years.[74] After the Alliance for European Integration lost a no confidence vote, the Pro-European Coalition was formed on 30 May 2013.[75]

Banking crisis[edit]

In November 2014, Moldova’s central bank took control of Banca de Economii, the country’s largest lender, and two smaller institutions, Banca Sociala and Unibank. Investigations into activities at these three banks uncovered large-scale fraud by means of fraudulent loans to business entities controlled by a Moldovan-Israeli business oligarch, Ilan Shor, of funds worth about 1 billion U.S. dollars.[76] The large scale of the fraud compared to the size of the Moldovan economy is cited as tilting the country’s politics in favour of the pro-Russian Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova.[77] In 2015, Shor was still at large, after a period of house arrest.

Pavel Filip’s government (2016-2019)[edit]

Following a period of political instability and massive public protests, a new government led by Pavel Filip was invested in January 2016.[78] Concerns over statewide corruption, the independence of the judiciary system, and the nontransparency of the banking system were expressed. Germany’s broadcaster Deutsche Welle also raised concerns about the alleged influence of Moldovan oligarch Vladimir Plahotniuc over the Filip government.[79]

In the December 2016 presidential election, Socialist, pro-Russian Igor Dodon was elected as the new president of the republic.[80]

2019 constitutional crisis[edit]

In 2019, from 7 to 15 June, the Moldovan government went through a period of dual power in what is known as the 2019 Moldovan constitutional crisis. On 7 June, the Constitutional Court, which is largely believed to be controlled by Vladimir Plahotniuc[81] from the Democratic Party, announced that they had temporarily removed the sitting president, Igor Dodon, from power due to his ‘inability’ to call new parliamentary elections as the parliament did not form a coalition within three months of the validation of the election results. According to Moldovan constitutional law, the president may call snap elections if no government is formed after three months.[82] However, on 8 June, the NOW Platform DA and PAS reached an agreement with the Socialist party forming a government led by Maia Sandu as the new prime minister, pushing the Democratic Party out of power.[83] This new government was also supported by Igor Dodon. The new coalition and Igor Dodon argued that the president may call snap elections after consulting the parliament but is not obliged to do so. Additionally, because the election results were verified on 9 March, three months should be interpreted as three calendar months, not 90 days as was the case. The former prime minister, Pavel Filip from the Democratic Party, said that new parliamentary elections would be held on 6 September and refused to recognize the new coalition, calling it an illegal government. After a week of dual government meetings, some protest, and the international community mostly supporting the new government coalition, Pavel Filip stepped down as prime minister but still called for new elections.[84] The Constitutional Court reversed the decision on 15 June, effectively ending the crisis.[85]

COVID-19 pandemic[edit]

In March 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the government called a «national red code alert» as the number of coronavirus cases in the country rose to six on 13 March 2020. Government «banned all gatherings of over 50 people until 1 April 2020 and closed all schools and kindergartens in an attempt to curb the spread of the virus». Flights were banned to Spain, Italy, France, Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Cyprus, Germany, Ireland, the U.K., Poland, Portugal and Romania.[86] On 17 March, Parliament declared a state of emergency for at least 60 days, suspended all international flights and closed borders with neighbours Romania and Ukraine. Moldova reported 29 cases of the disease on 17 March 2020.[87] The country reported its first death from the disease on 18 March 2020, when the total number of cases reached 30.[88]

Presidency of Maia Sandu since 2020[edit]

In the November 2020 presidential election, the pro-European opposition candidate Maia Sandu was elected as the new president of the republic, defeating incumbent pro-Russian president Igor Dodon and thus becoming the first female elected president of Moldova.[89] In December 2020, Prime Minister Ion Chicu, who had led a pro-Russian government since November 2019, resigned a day before Sandu was sworn in.[90] The parliament, dominated by pro-Russian Socialists, did not accept any Prime Minister candidate proposed by the new president.[91] On 28 April 2021, Sandu dissolved the Parliament of the Republic of Moldova after the Constitutional Court ended Moldova’s state of emergency which had been brought about by the coronavirus pandemic.[92] Parliamentary elections took place on 11 July 2021.[93] The snap parliamentary elections resulted in a landslide win for the pro-European Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS).[94] On 6 August 2021, the Natalia Gavrilița-led cabinet was sworn in to office with 61 votes, all from the Party of Action and Solidarity (PAS).[95] She resigned on 10 February 2023.[96][97]

Russian invasion of neighbouring Ukraine[edit]

In February 2022 Sandu condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine, calling it «a blatant breach of international law and of Ukrainian sovereignty and territorial integrity.»[98] Prime Minister Natalia Gavrilita stated on 28 February 2022 that Moldova should rapidly move to become a member of the European Union;[99] the country submitted a formal application for EU membership on 3 March 2022,[100] and was subsequently granted the status of candidate country by the European Council on 23 June 2022[101] along with Ukraine.

On 26 April 2022, authorities from the Transnistria region said two transmitting antennas broadcasting Russian radio programs at Grigoriopol transmitter broadcasting facility near the town of Maiac in the Grigoriopol District near the Ukrainian border had been blown up and the previous evening, the premises of the Transnistrian state security service had been attacked.[102] The Russian army has a military base and a large ammunition dump in the region. Russia has about 1,500 soldiers stationed in breakaway Transnistria. They are supposed to serve there as peacekeepers.[102]

On 24 May 2022, the former president of Moldova, Igor Dodon, was arrested. Dodon, leader of Moldova’s main pro-Russian opposition, the Socialist Party, was accused of taking bribes. Moldova’s pro-Western and pro-Russian factions became increasingly divided since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.[103]

On 31 October 2022, Moldova’s Interior Ministry said that debris from a Russian missile landed in the northern village of Naslavcea after a Russian fusillade was intercepted by air defenses in neighboring Ukraine. The Ministry reported no people were hurt but the windows of several residential homes were shattered. The Russian strike was targeting a Ukrainian dam on the Nistru river that runs through Moldova and Ukraine.[104] On 5 December, another missile fell near the city of Briceni as Russia launched another wave of missile strikes against Ukraine.[105] Yet another missile fell into Larga on 14 January 2023 as a result of another wave of missile strikes against Ukraine.[106][107]

Government[edit]

Moldova is a unitary parliamentary representative democratic republic. The 1994 Constitution of Moldova sets the framework for the government of the country. A parliamentary majority of at least two-thirds is required to amend the Constitution of Moldova, which cannot be revised in times of war or national emergency. Amendments to the Constitution affecting the state’s sovereignty, independence, or unity can only be made after a majority of voters support the proposal in a referendum. Furthermore, no revision can be made to limit the fundamental rights of people enumerated in the Constitution.[108] The country’s central legislative body is the unicameral Moldovan Parliament (Parlament), which has 101 seats, and whose members are elected by popular vote on party lists every four years.

The head of state is the President of Moldova, who between 2001 and 2015 was elected by the Moldovan Parliament, requiring the support of three-fifths of the deputies (at least 61 votes). This system was designed to decrease executive authority in favour of the legislature. Nevertheless, the Constitutional Court ruled on 4 March 2016, that this constitutional change adopted in 2000 regarding the presidential election was unconstitutional,[109] thus reverting the election method of the president to a two-round system direct election. The president appoints a prime minister who functions as the head of government, and who in turn assembles a cabinet, both subject to parliamentary approval.

The 1994 constitution also establishes an independent Constitutional Court, composed of six judges (two appointed by the President, two by Parliament, and two by the Supreme Council of Magistrature), serving six-year terms, during which they are irremovable and not subordinate to any power. The court is invested with the power of judicial review over all acts of parliament, over presidential decrees, and over international treaties signed by the country.[108]

Internal affairs[edit]

On 19 December 2016, Moldovan MPs approved raising the retirement age to 63 years[110] from the current level of 57 for women and 62 for men, a reform that is part of a 3-year-old assistance program agreed with the International Monetary Fund. The retirement age will be lifted gradually by a few months every year until it is fully in effect in 2028.

Life expectancy in the ex-Soviet country is 67.5 years for men and 75.5 years for women, both among the poorest in Europe. In a country with a population of 3.5 million, of which 1 million are abroad, there are more than 700,000 pensioners.

Foreign relations[edit]

After achieving independence from the Soviet Union, Moldova’s foreign policy was designed with a view to establishing relations with other European countries, neutrality, and European Union integration. In 1995 the country was admitted to the Council of Europe.

In addition to its participation in NATO’s Partnership for Peace programme, Moldova is also a member state of the United Nations, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), the North Atlantic Cooperation Council, the World Trade Organization, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the Francophonie and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development.

In June 2022, Moldova became a recognised candidate for membership of the European Union.

In 2005, Moldova and the European Union established an action plan that sought to improve cooperation between Moldova and the union. At the end of 2005, the European Union Border Assistance Mission to Moldova and Ukraine (EUBAM) was established at the joint request of the presidents of Moldova and Ukraine. EUBAM assists the Moldovan and Ukrainian governments in approximating their border and customs procedures to EU standards and offers support in both countries’ fight against cross-border crime.

After the 1990–1992 War of Transnistria, Moldova sought a peaceful resolution to the conflict in the Transnistria region by working with Romania, Ukraine, and Russia, calling for international mediation, and co-operating with the OSCE and UN fact-finding and observer missions. The foreign minister of Moldova, Andrei Stratan, repeatedly stated that the Russian troops stationed in the breakaway region were there against the will of the Moldovan government and called on them to leave «completely and unconditionally».[111] In 2012, a security zone incident resulted in the death of a civilian, raising tensions with Russia.[112]

In September 2010, the European Parliament approved a grant of €90 million to Moldova.[113] The money was to supplement US$570 million in International Monetary Fund loans,[114] World Bank and other bilateral support already granted to Moldova. In April 2010, Romania offered Moldova development aid worth of €100 million while the number of scholarships for Moldovan students doubled to 5,000.[115] According to a lending agreement signed in February 2010, Poland provided US$15 million as a component of its support for Moldova in its European integration efforts.[116] The first joint meeting of the Governments of Romania and Moldova, held in March 2012, concluded with several bilateral agreements in various fields.[117][118] The European orientation «has been the policy of Moldova in recent years and this is the policy that must continue,» Nicolae Timofti told lawmakers before his election in 2012.[119][full citation needed]

On 29 November 2013, at a summit in Vilnius, Moldova signed an association agreement with the European Union dedicated to the European Union’s ‘Eastern Partnership’ with ex-Soviet countries.[120] The ex-Romanian President Traian Băsescu stated that Romania will make all efforts for Moldova to join the EU as soon as possible. Likewise, Traian Băsescu declared that the unification of Moldova with Romania is the next national project for Romania, as more than 75% of the population speaks Romanian.[121]

Moldova signed the Association Agreement with the European Union in Brussels on 27 June 2014. The signing came after the accord was drafted in Vilnius in November 2013.[122][123]

Religious leaders play a role in shaping foreign policy. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the Russian Government has frequently used its connections with the Russian Orthodox Church to block and stymie the integration of former Soviet states like Moldova into the West.[124]

Moldova signed the membership application to join the EU on 3 March 2022.[125] On 23 June 2022, Moldova was officially granted candidate status by EU leaders.[126]

Military[edit]

The Moldovan armed forces consists of the Ground Forces and Air Force. Moldova has accepted all relevant arms control obligations of the former Soviet Union. On 30 October 1992, Moldova ratified the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, which establishes comprehensive limits on key categories of conventional military equipment and provides for the destruction of weapons in excess of those limits. The country acceded to the provisions of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in October 1994 in Washington, D.C. It does not have nuclear, biological, chemical or radiological weapons. Moldova joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s Partnership for Peace on 16 March 1994.

Moldova is committed to a number of international and regional control of arms regulations such as the UN Firearms Protocol, Stability Pact Regional Implementation Plan, the UN Programme of Action (PoA) and the OSCE Documents on Stockpiles of Conventional Ammunition.

Since declaring independence in 1991, Moldova has participated in UN peacekeeping missions in Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, Sudan and Georgia.

Moldova signed a military agreement with Romania to strengthen regional security. The agreement is part of Moldova’s strategy to reform its military and cooperate with its neighbours.[127]

On 12 November 2014, the US donated to Moldovan Armed Forces 39 Humvees and 10 trailers, with a value of US$700,000, to the 22nd Peacekeeping Battalion of the Moldovan National Army to «increase the capability of Moldovan peacekeeping contingents.»[128]

Human rights[edit]

According to Amnesty International, as of 2004 «Torture and other ill-treatment in police detention remained widespread; the state failed to carry out prompt and impartial investigations and police officers sometimes evaded penalties. Political dissidents from Ilașcu Group were released from arbitrary detention in the break-away Transdinester region only after an order of the European Court of Human Rights.»[129] In 2009, when Moldova experienced its most serious civil unrest in a decade, several civilians, including Valeriu Boboc, were killed and many more injured.[130]

According to Human Rights Report of the United States Department of State, released in April 2011, «In contrast to the previous year, there were no reports of killings by security forces. During the year reports of government exercising undue influence over the media substantially decreased.» But «Transnistrian authorities continued to harass independent media and opposition lawmakers; restrict freedom of association, movement, and religion; and discriminate against Romanian speakers.»[131] Moldova «has made noteworthy progress on religious freedom since the era of the Soviet Union, but it can still take further steps to foster diversity,» said the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief Heiner Bielefeldt, in Chișinău, in September 2011.[132] Moldova improved its legislation by enacting the Law on Preventing and Combating Family Violence, in 2008.[133]

Administrative divisions[edit]

Moldova is divided into 32 districts (raioane, singular raion), three municipalities and two autonomous regions (Gagauzia and the Left Bank of the Dniester).[134] The final status of Transnistria is disputed, as the central government does not control that territory. 10 other cities, including Comrat and Tiraspol, the administrative seats of the two autonomous territories, also have municipality status.

Moldova has 66 cities (towns), including 13 with municipality status, and 916 communes. Another 700 villages are too small to have a separate administration and are administratively part of either cities (41 of them) or communes (659). This makes for a total of 1,682 localities in Moldova, two of which are uninhabited.[135]

Largest cities in Moldova Source: Moldovan Census (2004); Note: 1. World Gazetteer. Moldova: largest cities 2004. 2. Pridnestrovie.net 2004 Census 2004. 3. National Bureau of Statistics of Moldova |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Pop. | Rank | Pop. | ||||

Chișinău  Tiraspol |

1 | Chișinău | 644,204 | 11 | Comrat | 20,113 |  Bălți  Bender |

| 2 | Tiraspol | 129,500 | 12 | Strășeni | 18,376 | ||

| 3 | Bălți | 102,457 | 13 | Durlești | 17,210 | ||

| 4 | Bender | 91,000 | 14 | Ceadîr-Lunga | 16,605 | ||

| 5 | Rîbnița | 46,000 | 15 | Căușeni | 15,939 | ||

| 6 | Ungheni | 30,804 | 16 | Codru | 15,934 | ||

| 7 | Cahul | 30,018 | 17 | Edineț | 15,520 | ||

| 8 | Soroca | 22,196 | 18 | Drochia | 13,150 | ||

| 9 | Orhei | 21,065 | 19 | Ialoveni | 12,515 | ||

| 10 | Dubăsari | 25,700 | 20 | Hîncești | 12,491 |

The largest city in Moldova is Chișinău with a population of 635,994 people.

Geography[edit]

Moldova lies between latitudes 45° and 49° N, and mostly between meridians 26° and 30° E (a small area lies east of 30°). The total land area is 33,851 km2 (13,070 sq mi)

The largest part of the country (around 88% of the area) lies in Bessarabia region, between Prut and Dniester rivers, while a narrow strip in the east is located in Transnistria (east of the Dniester). The western border of Moldova is formed by the Prut river, which joins the Danube before flowing into the Black Sea. Moldova has access to the Danube for only about 480 m (1,575 ft), and Giurgiulești is the only Moldovan port on the Danube. In the east, the Dniester is the main river, flowing through the country from north to south, receiving the waters of Răut, Bîc, Ichel, Botna. Ialpug flows into one of the Danube limans, while Cogâlnic into the Black Sea chain of limans.

The country is landlocked, though it is close to the Black Sea; at its closest point it is separated from the Dniester Liman, an estuary of the Black Sea, by only 3 km of Ukrainian territory. While most of the country is hilly, elevations never exceed 430 m (1,411 ft) – the highest point being the Bălănești Hill. Moldova’s hills are part of the Moldavian Plateau, which geologically originate from the Carpathian Mountains. Its subdivisions in Moldova include the Dniester Hills (Northern Moldavian Hills and Dniester Ridge), the Moldavian Plain (Middle Prut Valley and Bălți Steppe), and the Central Moldavian Plateau (Ciuluc-Soloneț Hills, Cornești Hills—Codri Massive, «Codri» meaning «forests»—Lower Dniester Hills, Lower Prut Valley, and Tigheci Hills). In the south, the country has a small flatland, the Bugeac Plain. The territory of Moldova east of the river Dniester is split between parts of the Podolian Plateau, and parts of the Eurasian Steppe.

The country’s main cities are the capital Chișinău, in the centre of the country, Tiraspol (in the eastern region of Transnistria), Bălți (in the north) and Bender (in the south-east). Comrat is the administrative centre of Gagauzia.

Climate[edit]

Moldova has a climate which is moderately continental; its proximity to the Black Sea leads to the climate being mildly cold in the autumn and winter and relatively cool in the spring and summer.[136]

The summers are warm and long, with temperatures averaging about 20 °C (68 °F) and the winters are relatively mild and dry, with January temperatures averaging −4 °C (25 °F). Annual rainfall, which ranges from around 600 mm (24 in) in the north to 400 mm (16 in) in the south, can vary greatly; long dry spells are not unusual. The heaviest rainfall occurs in early summer and again in October; heavy showers and thunderstorms are common. Because of the irregular terrain, heavy summer rains often cause erosion and river silting.

The highest temperature ever recorded in Moldova was 41.5 °C (106.7 °F) on 21 July 2007 in Camenca.[137] The lowest temperature ever recorded was −35.5 °C (−31.9 °F) on 20 January 1963 in Brătușeni, Edineț county.[138]

| Location | July (°C) | July (°F) | January (°C) | January (°F) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chișinău | 27/17 | 81/63 | 1/−4 | 33/24 |

| Tiraspol | 27/15 | 81/60 | 1/−6 | 33/21 |

| Bălți | 26/14 | 79/58 | −0/−7 | 31/18 |

Biodiversity[edit]

Phytogeographically, Moldova is split between the East European Plain and the Pontic–Caspian steppe of the Circumboreal Region within the Boreal Kingdom. It is home to three terrestrial ecoregions: Central European mixed forests, East European forest steppe, and Pontic steppe.[140] Forests currently cover only 11% of Moldova, though the state is making efforts to increase their range. It had a 2019 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 2.2/10, ranking it 158th globally out of 172 countries.[141] Game animals, such as red deer, roe deer and wild boar can be found in these wooded areas.[142]

| Scientific reserves in Moldova | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Location | Established | Area |

| Codru Reserve | Strășeni | 1971 | 5,177 hectares (52 km2) |

| Iagorlîc | Dubăsari | 1988 | 836 hectares (8 km2) |

| Lower Prut | Cahul | 1991 | 1,691 hectares (17 km2) |

| Plaiul Fagului | Ungheni | 1992 | 5,642 hectares (56 km2) |

| Pădurea Domnească | Glodeni | 1993 | 6,032 hectares (60 km2) |

The environment of Moldova suffered extreme degradation during the Soviet period, when industrial and agricultural development proceeded without regard for environmental protection.[142] Excessive use of pesticides resulted in heavily polluted topsoil, and industries lacked emission controls.[142] Founded in 1990, the Ecological Movement of Moldova, a national, non-governmental, nonprofit organization which is a member of the International Union for Conservation of Nature has been working to restore Moldova’s damaged natural environment.[142] The movement is national representative of the Center «Naturopa» of the Council of Europe and United Nations Environment Programme of the United Nations.[145]

Once possessing a range from the British Isles through Central Asia over the Bering Strait into Alaska and Canada’s Yukon as well as the Northwest Territories, saigas survived in Moldova and Romania into the late 18th century. Deforestation, demographic pressure, as well as excessive hunting eradicated the native saiga herds which is currently threatened with extinction. They were considered a characteristic animal of Scythia in antiquity. Historian Strabo referred to the saigas as the kolos, describing it as «between the deer and ram in size» which (understandably but wrongly) was believed to drink through its nose.[146]

Another animal which was extinct in Moldova since the 18th century until recently was the European Wood Bison or wisent. The species was reintroduced with the arrival of three European bison from Białowieża Forest in Poland several days before Moldova’s Independence Day on 27 August 2005.[147] Moldova is currently interested in expanding their wisent population, and began talks with Belarus in 2019 regarding a bison exchange program between the two countries.[148]

Economy[edit]

A proportional representation of Moldova exports, 2019

After the breakup of the USSR in 1991, energy shortages, political uncertainty, trade obstacles and weak administrative capacity contributed to the decline of Moldova’s economy. As a part of an ambitious economic liberalization effort, Moldova introduced a convertible currency, liberalized all prices, stopped issuing preferential credits to state enterprises, backed steady land privatization, removed export controls, and liberalized interest rates. The government entered into agreements with the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to promote growth.

The economy subsequently declined from 1991 to 1999. Since 2000, however, the country’s GDP (PPP) grew significantly:[15][149]

| 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.41% | 9.07% | 9.76% | 10.67% | 10.13% | 10.99% | 6.80% | −0.70% | 8.90% | 1.80% | −1.10% |

Although estimates point to possible modest overvaluation of the real exchange rate, external competitiveness appears broadly adequate as reflected in strong sustained export performance.[150] However, the near-term economic outlook is weak. Main risks to the near-term outlook relate to serious vulnerabilities and governance issues in the banking sector, policy slippages in the run up to the elections, intensification of geopolitical tensions in the region, and a further slowdown in activity in main trading partners.

Moldova remains highly vulnerable to fluctuations in remittances from workers abroad (which constitute 24 percent of GDP), exports to the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and European Union (EU) (88 per cent of total exports), and donor support (about 10 per cent of government spending). The main transmission channels through which adverse exogenous shocks could impact the Moldovan economy are remittances (also due to potentially returning migrants), external trade, and capital flows.

Moldova largely achieved the main objectives of the combined ECF/EFF (IMF financial credit) supported program. The economy recovered from the drought-related contraction in 2012.

| Year | Economic growth |

Year | Economic growth |

Year | Economic growth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | -7,5% | 2001 | +6,1% | 2011 | +6,4% |

| 1992 | -29,0% | 2002 | +7,8% | 2012 | -0,7% |

| 1993 | -1,2% | 2003 | +6,6% | 2013 | +8,9% |

| 1994 | -30,9% | 2004 | +7,4% | 2014 | +4,6% |

| 1995 | -1,4% | 2005 | +7,5% | 2015 | -0,5% |

| 1996 | -5,9% | 2006 | +4,8% | 2016 | +2,0% |

| 1997 | +1,6% | 2007 | +3,0% | 2017 | +4,5% |

| 1998 | -6,5% | 2008 | +7,8% | ||

| 1999 | -3,4% | 2009 | -6,5% | ||

| 2000 | +2,1% | 2010 | +6,9% | ||

| Note:[151][152][153][154][155][156] |

The gross average monthly salary in the Republic of Moldova has registered a steady positive growth after 1999, being 5906 lei or 298 euros in 2018.

Corporate governance in the banking sector is a major concern. In line with FSAP recommendations, significant weaknesses in the legal and regulatory frameworks must be urgently addressed to ensure stability and soundness of the financial sector. Moldova has achieved a substantial degree of fiscal consolidation in recent years, but this trend is now reversing. Resisting pre-election pressures for selective spending increases and returning to the path of fiscal consolidation would reduce reliance on exceptionally high donor support. Structural fiscal reforms would help safeguard sustainability.[150] Monetary policy has been successful in maintaining inflation within the NBM’s target range. The implementation of structural reforms outlined in the National Development Strategy (NDS) Moldova 2020—especially in the business environment, physical infrastructure, and human resources development areas—would help boost potential growth and reduce poverty.[150] Moldova’s remarkable recovery from the severe recession of 2009 was largely the result of sound macroeconomic and financial policies and structural reforms. Despite a small contraction in 2012, Moldova’s economic performance was among the strongest in the region during 2010–13. Economic activity grew cumulatively by about 24 percent; consumer price inflation was brought under control; and real wages increased cumulatively by about 13 percent. This expansion was made possible by adequate macroeconomic stabilization measures and ambitious structural reforms implemented in the wake of the crisis under a Fund-supported program. In November 2013, Moldova initialed an Association Agreement with the EU which includes provisions establishing a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA).

| The country | Average monthly salary (euro) 2018 |

|---|---|

| Moldova[157] | €298 |

| Romania[158] | €966 |

| Ukraine[159] | €276 |

| Russia[160] | €534 |

Real GPD per capita development of Moldova, 1973 to 2018

A political crisis in early 2013 led to policy slippages in the fiscal and financial areas. The political crisis that broke out in early 2013 was resolved with the appointment of a government supported by a pro-European center-right/center coalition in May 2013. However, delays in policy implementation prevented completion of the final reviews under the ECF/EFF arrangements.[citation needed]

Despite a sharp decline in poverty in recent years, Moldova remains one of the poorest countries in Europe and structural reforms are needed to promote sustainable growth. Based on the Europe and Central Asia (ECA) regional poverty line of US$5/day (PPP), 55 percent of the population was poor in 2011. While this was significantly lower than 94 percent in 2002, Moldova’s poverty rate is still more than double the ECA average of 25 percent. The NDS—Moldova (National Development System) 2020, which was published in November 2012, focuses on several critical areas to boost economic development and reduce poverty. These include education, infrastructure, financial sector, business climate, energy consumption, pension system, and judicial framework. Following the regional financial crisis in 1998, Moldova has made significant progress towards achieving and retaining macroeconomic and financial stabilization. It has, furthermore, implemented many structural and institutional reforms that are indispensable for the efficient functioning of a market economy. These efforts have helped maintain macroeconomic and financial stability under difficult external circumstances, enabled the resumption of economic growth and contributed to establishing an environment conducive to the economy’s further growth and development in the medium term.[citation needed]

The government’s goal of EU integration has resulted in some market-oriented progress. Moldova experienced better than expected economic growth in 2013 due to increased agriculture production, to economic policies adopted by the Moldovan government since 2009, and to the receipt of EU trade preferences connecting Moldovan products to the world’s largest market. Moldova has signed the Association Agreement and the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement with the European Union during summer 2014.[161] Moldova has also achieved a Free Visa Regime[162] with the EU which represents the biggest achievement of Moldovan diplomacy since independence.[163] Still, growth has been hampered by high prices for Russian natural gas, a Russian import ban on Moldovan wine, increased foreign scrutiny of Moldovan agricultural products, and by Moldova’s large external debt. Over the longer term, Moldova’s economy remains vulnerable to political uncertainty, weak administrative capacity, vested bureaucratic interests, corruption, higher fuel prices, Russian pressure, and the separatist regime in Moldova’s Transnistria region.[164]

According to IMF World Economic Outlook April 2014, the Moldovan GDP (PPP) per capita is 3,927 International Dollars,[165][166] excluding grey economy and tax evasion.

Energy[edit]

With few natural energy resources, Moldova imports almost all of its energy supplies from Russia and Ukraine. Moldova’s dependence on Russian energy is underscored by a growing US$5 billion debt to Russian natural gas supplier Gazprom, largely the result of unreimbursed natural gas consumption in the separatist Transnistria region. In August 2013, work began on a new pipeline between Moldova and Romania that may eventually break Russia’s monopoly on Moldova’s gas supplies.[164] Moldova is a partner country of the EU INOGATE energy programme, which has four key topics: enhancing energy security, convergence of member state energy markets on the basis of EU internal energy market principles, supporting sustainable energy development, and attracting investment for energy projects of common and regional interest.[167]

Wine industry[edit]

The country has a well-established wine industry. It has a vineyard area of 147,000 hectares (360,000 acres), of which 102,500 ha (253,000 acres) are used for commercial production. Most of the country’s wine production is made for export. Many families have their own recipes and grape varieties that have been passed down through the generations. There are 3 historical wine regions: Valul lui Traian (south west), Stefan Voda (south east) and Codru (center), destined for the production of wines with protected geographic indication.[16] Mileștii Mici is the home of the largest wine cellar in the world. It stretches for 200 km (120 mi) (though only 55 km (34 mi) is in use) and holds almost 2 million bottles of wine[168]

Agriculture[edit]

Moldova’s rich soil and temperate continental climate (with warm summers and mild winters) have made the country one of the most productive agricultural regions since ancient times, and a major supplier of agricultural products in southeastern Europe. In agriculture, the economic reform started with the land cadastre reform.[169]

Moldova’s agricultural products include vegetables, fruits, grapes, wine, and grains.[170]

Transport[edit]

The main means of transportation in Moldova are railways 1,138 km (707 mi) and a highway system (12,730 km or 7,910 mi overall, including 10,937 km or 6,796 mi of paved surfaces). The sole international air gateway of Moldova is the Chișinău International Airport. The Giurgiulești terminal on the Danube is compatible with small seagoing vessels. Shipping on the lower Prut and Nistru rivers plays only a modest role in the country’s transportation system.

Telecommunications[edit]

The first million mobile telephone users were registered in September 2005. The number of mobile telephone users in Moldova increased by 47.3% in the first quarter of 2008 against the last year and exceeded 2.89 million.[171]

In September 2009, Moldova was the first country in the world to launch high-definition voice services (HD voice) for mobile phones, and the first country in Europe to launch 14.4 Mbit/s mobile broadband on a national scale, with over 40% population coverage.[172]

As of 2010, there are around 1,295,000 Internet users in Moldova with overall Internet penetration of 35.9%.[173]

On 6 June 2012, the Government approved the licensing of 4G / LTE for mobile operators.[174]

Demographics[edit]

Ethnic composition[edit]

As of the 2014 census, Moldovans were the largest ethnic group of Moldova (75.1% of the population). In addition, 7.0% of the population declared themselves Romanians, amid the controversy over ethnic and linguistic identity in Moldova. Although historical, the polarization based on ethnolinguistic criteria of the majority ethnic group reappeared with the national revival movement of the late 1980s, and, so far, there is no consensus regarding the mainstream identity in the Republic of Moldova (Moldovan or Romanian).[175][176]

The country also has important minority ethnic communities, as shown in the table below. Gagauz, 4.4% of the population, are Christian Turkic people. Greeks, Armenians, Poles, Ukrainians, although not numerous, were present as early as the 17th century, and have contributed cultural marks. The 19th century saw the arrival of many more Ukrainians from Podolia and Galicia, as well as new communities, such as Lipovans, Russians, Bulgarians, and Germans. Most of Moldova’s Jewish population emigrated between 1979 and 2004.

| Population of Moldova according to ethnic group (Censuses 1959–2014) | ||||||||||||

| Ethnic group | 1959[177] | 1970[178] | 1979[179] | 1989[180] | 2004**[181] (without Transnistria) |

2014[182][181] (without Transnistria) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Moldovans * | 1,886,566 | 65.41 | 2,303,916 | 64.56 | 2,525,687 | 63.95 | 2,794,749 | 64.47 | 2,564,849 | 76.12 | 2,068,058 | 75.07 |

| Romanians * | 1,663 | 0.06 | 1,581 | 0.04 | 1,657 | 0.04 | 2,477 | 0.06 | 73,276 | 2.17 | 192,800 | 7.00 |

| Ukrainians | 420,820 | 14.59 | 506,560 | 14.19 | 560,679 | 14.20 | 600,366 | 13.85 | 282,406 | 8.38 | 181,035 | 6.57 |

| Gagauzians | 95,856 | 3.32 | 124,902 | 3.50 | 138,000 | 3.49 | 153,458 | 3.54 | 147,500 | 4.38 | 126,010 | 4.57 |

| Russians | 292,930 | 10.16 | 414,444 | 11.61 | 505,730 | 12.81 | 562,069 | 12.97 | 201,218 | 5.97 | 111,726 | 4.06 |

| Bulgarians | 61,652 | 2.14 | 73,776 | 2.07 | 80,665 | 2.04 | 88,419 | 2.04 | 65,662 | 1.95 | 51,867 | 1.88 |

| Romani | 7,265 | 0.25 | 9,235 | 0.26 | 10,666 | 0.27 | 11,571 | 0.27 | 12,271 | 0.36 | 9,323 | 0.34 |

| Belarusians | 5,977 | 0.21 | 10,327 | 0.29 | 13,874 | 0.35 | 19,608 | 0.45 | 5,059 | 0.15 | 2,828 | 0.10 |

| Jews | 95,107 | 3.30 | 98,072 | 2.75 | 80,124 | 2.03 | 65,836 | 1.52 | 3,628 | 0.11 | 1,597 | 0.06 |

| Poles | 4,783 | 0.17 | 4,899 | 0.14 | 4,961 | 0.13 | 4,739 | 0.11 | 2,383 | 0.07 | 1,404 | 0.05 |

| Germans | 3,843 | 0.13 | 9,399 | 0.26 | 11,374 | 0.29 | 7,335 | 0.17 | 1,616 | 0.05 | 914 | 0.03 |

| Others | 7,947 | 0.28 | 11,734 | 0.33 | 16,049 | 0.41 | 24,590 | 0.57 | 9,444 | 0.28 | 7,157 | 0.26 |

| * There is an ongoing controversy, in part involving linguisitic definition of ethnicity, over whether Moldovans’ self-identification constitutes an ethnic group distinct and apart from Romanians, or a subset. | ||||||||||||

| ** There were numerous allegations that the ethnic affiliation numbers were rigged: 7 out of 10 observer groups of the Council of Europe reported a significant number of cases where census-takers recommended respondents declare themselves Moldovans rather than Romanians. Complicating the interpretation of the results, 18.8% of respondents that identified themselves as Moldovans declared Romanian to be their native language.[183] |