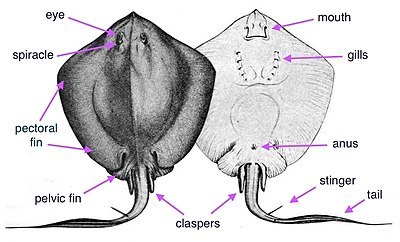

(Batomorpha, или Batoidei), надотряд пластиножаберных рыб. Известны с верхней юры, многочисленны с верхнего мела. Тело уплощённое, широкое, обычно дисковидное или ромбовидное, дл. от неск. см до 6—7 м, при макс, массе до 2,5 т. Кожа голая или покрыта шипами. Жаберных щелей 5, расположены на брюшной стороне тела. Края грудных плавников сращены с боками головы и туловища. Спинные плавники на хвосте или их нет. Анальный, а часто и хвостовой плавники отсутствуют, грудные — сильно увеличены. Плотно прилегающие друг к другу, ортодентиновые, уплощённые и закруглённые зубы образуют мощную тёрку. Брызгальце на верх, стороне тела. 5 отрядов: пилорылообразные, гнюсообразные, хвостоколлообразные (Dasyatiformes), ромбо-скатообразные (Rajiformes) и рохлеобразные (Rhinobatiformes); 14 семейств, ок. 50 родов и 350 видов. Придонные рыбы, лишь немногие (мантовые и хвостоколовые) живут в толще воды. Преим. мор. рыбы, обитающие во всех океанах от мелководий до глубины 2700 м, нек-рые живут в тропич. реках (басc. Амазонки и др.). Бентофаги и хищники. Живородящие и яйцеживородящие, только ромбоскатообразные откладывают на дно крупные яйца, заключённые в роговую капсулу. Плодовитость от 1 до неск. десятков эмбрионов. Гнюсообразные имеют по бокам тела электрич. органы, у хвостоколовых есть острые хвостовые шипы, снабжённые ядоносной железой. В СССР более 10 видов из семейств скатовые (Rajidae) — в Чёрном, Азовском, северных и дальневост. морях и хвостоколовые — в Чёрном, Азовском и Японском морях. Объект промысла. Нек-рые С. опасны для человека. (см. 38_ТАБЛИЦА_38).

.(Источник: «Биологический энциклопедический словарь.» Гл. ред. М. С. Гиляров; Редкол.: А. А. Бабаев, Г. Г. Винберг, Г. А. Заварзин и др. — 2-е изд., исправл. — М.: Сов. Энциклопедия, 1986.)

ска́ты

надотряд пластиножаберных рыб. Ближайшие родственники акул, перешедшие к донной жизни и ставшие в процессе эволюции плоскими. Тело дл. от нескольких см до 6—7 м, при максимальной массе до 2,5 т, уплощённое, дисковидное или ромовидное, широкое и кажется ещё шире благодаря грудным плавникам, которые тянутся по бокам туловища, образуя треугольные, похожие на крылья, выступы. Эти плавники во время плавания волнообразно изгибаются, напоминая взмахи крыльев птиц, и рыбы как бы парят в воде, за что некоторых скатов называют «морскими орлами» или «морскими ястребами». Хвост у многих скатов узкий и вытянут в длину. У скатов-хвостоколов у основания хвоста имеется острый длинный шип с ядом, представляющим опасность для человека. У одних скатов кожа гладкая, у других есть шипы и колючки.

Скаты хорошо приспособлены к жизни на дне, где они, выслеживая добычу, частично зарываются в песок. Окраска верхней стороны тела маскировочная, соответствующая грунту.

У скатов, в отличие от акул, жаберные отверстия располагаются не на боках тела, а на брюхе. Анальный плавник и мигательная перепонка отсутствуют. Ни у одного ската нет характерных для многих акул острых, как лезвие, зубов. Их зубы имеют форму шипиков, либо закруглены и сильно уплощены.

Скаты широко распространены во всех морях и океанах, обитая в широком диапазоне глубин и температур. В водах России живут св. 10 видов из сем. скатовых (морская лисица и др.), которых называют также ромбовыми скатами. Молодь этих скатов заметно отличается от взрослых рыб пропорциями тела, развитием шипов на теле и др. Самки обычно крупнее самцов, у них более широкий диск тела и сильнее развиты шипы. Многие скаты – объекты промысла.

.(Источник: «Биология. Современная иллюстрированная энциклопедия.» Гл. ред. А. П. Горкин; М.: Росмэн, 2006.)

.

Русский

скат I

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | скат | ска́ты |

| Р. | ска́та | ска́тов |

| Д. | ска́ту | ска́там |

| В. | скат | ска́ты |

| Тв. | ска́том | ска́тами |

| Пр. | ска́те | ска́тах |

скат

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Приставка: с-; корень: -кат-.

Произношение

- МФА: ед. ч. [skat], мн. ч. [ˈskatɨ]

Семантические свойства

Значение

- ровная наклонная поверхность ◆ Базовая линия необходима для начала раскладки листов металлочерепицы на скате крыши как вверх, так и вниз от неё. ◆ После переправы чрез мост открывается аул Башин-Кале, расположенный на скате горы. ◆ От барского дома по скату горы до самой реки расстилался фруктовый сад. М. Ю. Лермонтов, «Я хочу рассказать вам…», 1836 г. [НКРЯ] ◆ Блиндаж был вырыт на скате лесистого холма. A. Н. Толстой, «Хождение по мукам», Книга первая: „Сёстры“, 1922 г. [НКРЯ]

- автомоб. то же, что шина ◆ Прежде чем сесть в кабину, он вразвалочку описал петлю вокруг машины, хмуро постучал носком туфля по скатам, проверяя, хорошо ли накачаны колёса. Николай Довгай, «Ключевая фигура»

- рег. действие по значению гл. скатываться ◆ Для некоторых это был бы скат в пропасть.

- ж.-д. комплект локомотивных колёсных пар, состоящий из ведущих и различного (в зависимости от типа локомотива) количества сцепных колёсных пар, а также поддерживающих передней и задней тележек; колесо или колёса на оси, или, преимущественно, колёсный стан, то есть четыре колеса на двух осях ◆ Чего там только не было! Сотни вагонных скатов, целые горы ржавого железа, рельсы, буфера, буксы — несколько тысяч тонн металла ржавело под открытым небом. Н. А. Островский, «Как закалялась сталь», 1930–1934 гг. [НКРЯ]

Синонимы

- —

- шина

- —

- —

Антонимы

- —

- —

- —

- —

Гиперонимы

- —

- —

- —

- колесо

Гипонимы

- склон

- —

- —

- —

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

Этимология

Происходит от гл. скатиться (скатить), далее из с- + катить, далее из праслав. *kotiti, *koti̯ǫ, от кот. в числе прочего произошли: русск. катить, катать, укр. ката́ти, словенск. kotáti «катать», чешск. kácet «опрокидывать, рубить (деревья)», укр. коти́ти, словенск. prekotíti «опрокинуть, перекатывать», польск. kасić się «охотиться» (но ср.: итал. cacciare «охотиться», исп. cazar — то же, из лат. captare?). Сюда же русск. качать, укр. качати. Сомнительно предположение о родстве с англ. skate «скользить», skate «конёк», голл. sсhааts — то же. Сравнение с лат. quatiō «трясу, толкаю», греч. πάσσω «посыпаю, насыпаю» (Лёвенталь) неприемлемо. Сомнительно сравнение с др.-инд. c̨ātáyati «повергает», к тому же тогда пришлось бы предположить чередование задненёбных. Использованы данные словаря М. Фасмера. См. Список литературы.

Метаграммы

- сват

- скот

- сказ, скан

Перевод

| наклонная поверхность | |

|

| шина | |

|

| действие | |

|

Анаграммы

- каст, Каст, Ктас, таск

|

|

Для улучшения этой статьи желательно:

|

скат II

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | скат | ска́ты |

| Р. | ска́та | ска́тов |

| Д. | ска́ту | ска́там |

| В. | ска́та | ска́тов |

| Тв. | ска́том | ска́тами |

| Пр. | ска́те | ска́тах |

скат

Существительное, одушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: -скат-.

Произношение

- МФА: ед. ч. [skat], мн. ч. [ˈskatɨ]

Семантические свойства

Значение

- ихтиол. хищная рыба из надотряда пластиножаберных, отличающаяся плоским телом и длинным узким хвостом ◆ Во время погружения видел большую мурену, кучу разноцветных рыбок, а потом мимо проплыл огромный скат.

Синонимы

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

- рыба, животное

Гипонимы

- манта, электрический скат

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

|

Этимология

Происходит от норв., шведск. skata «скат».

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

- белобровый скат

- электрический скат

Перевод

| Список переводов | |

|

скат III

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | скат | ска́ты |

| Р. | ска́та | ска́тов |

| Д. | ска́ту | ска́там |

| В. | скат | ска́ты |

| Тв. | ска́том | ска́тами |

| Пр. | ска́те | ска́тах |

скат

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: —.

Произношение

- МФА: ед. ч. [skat], мн. ч. [ˈskatɨ]

Семантические свойства

Значение

- карт. карточная игра с участием трёх игроков ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

Гиперонимы

- карточная игра

Гипонимы

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от ??

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

| Список переводов | |

|

скат IV

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

| падеж | ед. ч. | мн. ч. |

|---|---|---|

| Им. | скат | ска́ты |

| Р. | ска́та | ска́тов |

| Д. | ска́ту | ска́там |

| В. | скат | ска́ты |

| Тв. | ска́том | ска́тами |

| Пр. | ска́те | ска́тах |

скат

Существительное, неодушевлённое, мужской род, 2-е склонение (тип склонения 1a по классификации А. А. Зализняка).

Корень: —.

Произношение

- МФА: ед. ч. [skat], мн. ч. [ˈskatɨ]

Семантические свойства

техника

Значение

- муз. то же, что скэт; манера джазовой вокальной импровизации, при которой голос используется для имитации музыкального инструмента ◆ Отличительной особенностью вокала Джексона является его способность передавать эмоции без использования языка: с помощью его знаменитых вздохов, глотаний звуков, восклицаний, вскрикиваний. Он часто поёт скатом, искажает слова так, что их едва можно разобрать. Джозеф Вогель, «Человек в музыке» / перевод Ю. Сирош

Синонимы

- скэт

Антонимы

- —

Гиперонимы

Гипонимы

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от англ. scat.

Фразеологизмы и устойчивые сочетания

Перевод

| Список переводов | |

Библиография

Украинский

Морфологические и синтаксические свойства

ска́т

Существительное, одушевлённое, мужской род.

Корень: -скат-.

Произношение

Семантические свойства

Значение

- ихтиол. скат (хищная рыба из надотряда пластиножаберных, отличающаяся плоским телом и длинным узким хвостом) ◆ Отсутствует пример употребления (см. рекомендации).

Синонимы

Антонимы

Гиперонимы

Гипонимы

Родственные слова

| Ближайшее родство | |

Этимология

Происходит от норв., шведск. skata «скат».

Особенности и среда обитания рыбы скат

Рыба скат – древнейший обитатель водных глубин. Скаты – это таинственные существа. Они вместе с акулами – своими ближайшими родственниками являются древнейшими старожилами глубин вод.

Эти создания обладают очень многими интересными особенностями, чем и отличаются от других, плавающих в воде, представителей фауны. Учёные предполагают, что в доисторические времена далёкие предки акул и скатов по строению мало чем различались, но мириады прошедших лет сделали этих животных ни в чём не схожими, а сами особи обоих видов претерпели значительные изменения.

Современная рыба скат (на фото животного это хорошо заметно) характеризуется до чрезвычайности плоским телом и головой, причудливо сросшейся с грудными плавниками, что предаёт этому существу фантастический вид.

Окрас животного во многом зависит от мест его обитания: морских вод и пресных водоёмов. У этих существ, цвет верхней области тела бывает, как светлым, к примеру, песчаным, так разноцветным, с причудливым орнаментом или тёмным. Именно такая окраска помогает успешно маскироваться скатам от наблюдателей сверху, давая ему возможность слиться с окружающим пространством.

Нижняя часть этих плоских существ обычно бывает светлее верхней. На указанной стороне животного располагаются такие органы, как пасть и ноздри, а также жабры в количестве пяти пар. Хвост таких обитателей вод имеет бичеобразную форму.

Скаты являются очень обширной группой водных животных, не имеющих никакого отношения к млекопитающим. Скат – это рыба или точнее, существо, принадлежащее к разряду пластиножаберных хрящевых рыб.

По своим размерам указанные обитатели глубин также значительно отличаются между собой. Существует особи длиной всего несколько сантиметров. Другие метровой, а в некоторых случаях и более (до 7 метров) величины.

Тело скатов настолько плоское и длинное, напоминая собой, раскатанный скалкой блин, что края с боков существ похожи на крылья, представляя собой грудные плавники. В некоторых случаях размах их достигает двух метров и более.

Примером подобного может послужить скат, являющий членом семейства орляковых, длина тела которых доходит до пяти, а размах своеобразных крыльев до двух с половиной метров. Скат – хрящевая рыба. Это значит, что внутренности её строятся не из костей, как у акул и других животных, а из хрящей.

Расцветка ската дает ему возможность маскироваться на морском дне

Места обитания скатов столько же обширны, как и их многообразие. Таких животных можно встретить в водных глубинах на территории всей планеты, даже в Арктике и Антарктике. Но с таким же успехом они обживают тропические воды.

Глубина водоёмов, служащих пристанищем животных, аналогичным образом сильно варьируется. Рыба скат обитает и способна с успехом прижиться на мелководье, но также прекрасно приспосабливается существовать на глубине 2700 м.

Характер и образ жизни рыбы скат

Удивительные свойства различных видов скатов поражают воображение. К примеру, на побережьях Австралии можно наблюдать «летающих скатов». Встречаются также электрические рыбы скаты.

На фото «летающие» скаты

А подобная сила, данная им природой оказывается прекрасным оружием в борьбе за выживание. Такие существа способны парализовать жертву, используя собственное электричество, которое вырабатывают все скаты, но именно данный вид производит её в количестве до 220 вольт.

Такого разряда, который особенно сильным сказывается в воде, бывает вполне достаточно, чтобы парализовать отдельные части тела человека, и даже привести к смертельному исходу. Интереснейший из видов рыбы скат – морской дьявол. Это животное огромных размеров, по весу превосходящее две тонны.

О таких существах моряки складывали самые невероятные легенды, причинами возникновения которых явились неожиданные появлениям таких чудовищных по размерам морских рыб скатов из пучин перед глазами ошеломлённых путешественников.

Они стремглав выпрыгивали из воды, а затем исчезали в глубине, мелькая остроконечным хвостом, что часто становилось причиной панического ужаса. Однако, страхи были беспричинными, а подобные существа совершенно безобидны и даже миролюбиво по характеру.

На фото скат «морской дьявол»

А случаев нападения на людей за долгое время не было зафиксировано. Как раз наоборот, человек частенько употреблял в пищу их питательное и вкусное мясо, которое и поныне является компонентом и составной частью многих блюд, а также самых разнообразных экзотических рецептов.

Вот только процесс охоты на морского дьявола может превратиться в опасное занятие, ведь величина животного вполне позволяет ему перевернуть лодку с рыбаками. Основная часть жизни рыбы ската проходит у дна водоёмов. Эти животные даже отдыхают, зарывшись в ил или песок. Именно поэтому дыхательная система этих животных отличается от других рыб.

Дышат они не жабрами, а воздух попадает в их организм через приспособления, называемые брызгальцами, которые располагаются на его спине. Эти органы снабжены особым клапаном, помогающим защищать организм ската от посторонних частиц, попадающих внутрь со дна водоёма. Весь ненужный мусор, частички песка и грязи удаляются из брызгалец, выпускаемой скатом, струёй воды.

Передвигаются скаты также любопытным образом, совсем не пользуясь при плавании хвостом. Они машут плавниками, словно бабочки, а своеобразная форма тела помогает животным практически парить в воде, ввиду чего они являются отменными пловцами.

Питание ската

Рыба скат – хищное существо. Основной её пищей является рыба: лосось, сардины, кефаль или мойва. Крупные из видов могут прельститься на такую добычу, как осьминоги и крабы. Мелких разновидности довольствуются планктоном, а также небольшими рыбёшками.

Разнообразие скатов и их удивительные возможности проявляются также и на добывании пищи. Для охоты за своими жертвами различные виды этих фантастических существ применяют то оружие, которым их снабдила природа.

Электрический скат, настигнув добычу, обнимает её плавниками и оглушает электрическим разрядом, ожидая её смерти. А оружием колючехвостого ската является хвост, усеянный шипами, который он вонзает в противника. Поедая моллюсков и рачков, он использует особые выступающие пластины, заменяющие этому существу зубы, ими перемалывая свою добычу.

Размножение и продолжительность жизни рыбы скат

Некоторые виды скатов являются живородящими, другие откладывают в капсулы яйца. Существуют также разновидности, которые выполняют свою репродуктивные функцию промежуточным образом, являясь яйцеживородящими.

При вынашивании детёнышей организм матери питает эмбрионы, своеобразными выростами, проникающими в ротовую полость. Самка морского дьявола способна родить лишь одного детёныша, но размеры его очень внушительны, а вес составляет около 10 кг. А вот самка электрического ската, которая производит на свет живых детёнышей, способна увеличить род скатов иногда на 14 особей.

Величина новорожденных составляет всего 2 см, но с самой первой минуты существования они способны производить электричество. Срок жизни скатов чаще всего зависит от размера. Мелкие виды живут в среднем от 7 до 10 лет. Те, что покрупней, проживают дольше, примерно от 10 до 18 лет.

Некоторые разновидности: электрический скат, а также ряд других, к примеру, обитающий у Каймановых островов, где для таких представителей фауны существуют самые благоприятные условия, проживают жизнь сроком около четверти века.

| Скаты | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Скат-хвостокол Taeniura meyeni |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Научная классификация | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

промежуточные ранги

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Международное научное название | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Batomorphi |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Синонимы | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Отряды | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Скаты (лат. Batomorphi[1]) — один из двух надотрядов[К 1] пластиножаберных хрящевых рыб. Содержит пять отрядов и пятнадцать семейств. Для скатов характерно сильно уплощенное тело и большие грудные плавники, сросшиеся с головой. Пасть, ноздри и пять пар жабер находятся на плоской и, как правило, светлой нижней стороне. Хвост бичеобразной формы. Большинство скатов живёт в морской воде, однако существует и несколько пресноводных видов (моторо и другие) Верхняя сторона у скатов приспособлена по расцветке к тому или иному жизненному пространству и может варьировать от светло-песочной до чёрной. На верхней стороне расположены глаза и отверстия, в которые проникает вода для дыхания — брызгальца (первая пара жаберных щелей).

Скаты обитают во всех морях и океанах и живут как в холодных водах Арктики и Антарктики, так и в тропиках, диапазон температур среды обитания у них колеблется от 1,5 до 30 °С[3]. Эти рыбы встречаются как на мелководье, так и на глубине до 2700 м. Большинство видов скатов ведёт придонный образ жизни и питается моллюсками, раками и иглокожими. Пелагические виды питаются планктоном и мелкой рыбой.

Размеры скатов колеблются от нескольких сантиметров до 6—7 м в длину. Одним из наиболее известных видов скатов является манта (Manta birostris). Больших размеров достигают скаты из семейства орляковых, чей размах плавников может достигать 2,5 метра, а длина — до пяти метров; а также скаты из семейства хвостоколовых, достигающие 2,1 метра в ширину и до 5,5 метров в длину. Сравнительно крупный скат-хвостокол морской кот встречается в Чёрном и Азовском морях.

Особым «оружием» наделён отряд электрических скатов, чьи представители с помощью специального органа из преобразованных мышц могут парализовать добычу электрическими разрядами от 60 до 230 вольт и свыше 30 ампер[уточнить][источник не указан 889 дней].

Содержание

- 1 Анатомия и физиология

- 1.1 Чешуя

- 1.2 Нервная система

- 1.3 Электрические органы

- 2 Жизненный цикл

- 2.1 Размножение

- 3 Классификация

- 4 Различия между акулами и скатами

- 5 Взаимодействие с человеком

- 5.1 Использование

- 5.2 Опасность для человека

- 5.3 Охранный статус

- 6 Комментарии

- 7 Примечания

- 8 Литература

- 9 Ссылки

Анатомия и физиология

Чешуя

У многих видов скатов чешуя редуцирована[4]. Плакоидная чешуя, свойственная скатам, среди рыб является самой древней в филогенетическом плане. Чешуйки представляют собой ромбические пластинки, которые заканчиваются шипом, выступающим из кожи наружу. По строению и прочности чешуя близка к зубам, что даёт повод называть её кожными зубчиками. Зубчики эти имеют широкое основание, приплюснутую форму и очень рельефно очерченную коронку. Шип плакоидной чешуи отличается ещё более высокой прочностью, так как снаружи покрыт особой эмалью — витродентином, образуемым клетками базального слоя эпидермиса. Плакоидная чешуйка имеет полость, заполненную рыхлой соединительной тканью с кровеносными сосудами и нервными окончаниями. У некоторых видов скатов плакоидная чешуя видоизменена и выглядит как крупные бляшки на поверхности тела (например, морская лисица, Raja clavata) или колючки (например, синий хвостокол, Pteroplatytrygon violacea)[4].

Нервная система

У скатов (как и других хрящевых рыб) хорошо развиты три группы сенсорных органов: органы химической рецепции (параллельные обонянию и вкусу наземных животных), фоторецепции (зрение) и органов акустико-латеральной системы (орган боковой линии, ампулы Лоренцини). В соответствие с этим головной мозг скатов имеет три выделенных раздела: передний, отвечающий за химическую рецепцию (обонятельная луковица и обонятельная доля), средний, отвечающий за зрение (зрительные бугры) и задний отдел (включающий продолговатый мозг и мозжечок), который обрабатывает сигналы приходящие от органов акустико-латеральной системы. Степень развития каждого из отделов головного мозга связана с экологической ролью соответствующего сенсорного комплекса для данного вида.

Следует отметить высокую степень автономности спинного мозга у скатов как и у других водных холоднокровных животных[5].

Электрические органы

У скатов, как и у прочих электрических рыб, имеются органы, вырабатывающие электричество. Электрические органы представляют собой парные симметричные структуры, расположенные латерально, состоящие из собранных в столбики электрических пластин. У скатов их вес достигает 25 % массы рыбы, по внешнему виду они напоминают пчелиные соты. Один орган составляют примерно 600 вертикально поставленных шестигранных призм. Каждая призма, представляющая собой своеобразную батарею, в свою очередь состоит из 40 или менее электрических дисковидных пластинок, разделённых студенистой соединительной тканью. У скатов электрические органы расположены в хвостовой части тела. Морские скаты генерируют разряды меньшего напряжения, но высокой силы тока (40—60 В при силе тока 50—60 А)[6].

Жизненный цикл

Размножение

Скаты — раздельнополые животные.

Скаты размножаются, откладывая на дно заключённые в капсулу яйца или живорождением. У электрических скатов и хвостоколов в матке дополнительно развиваются специальные ворсинки, или трофотении, снабжающие эмбрион питательными веществами.

Классификация

Классификация надотряда скатов в настоящее время подвергается пересмотру, однако молекулярные доказательства опровергают гипотезу о происхождении скатов от акул[7].

| Отряд | Фото | Название | Семейств | Родов | Видов | Характеристики | Источники | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Всего | ||||||||||

| Torpediniformes |

|

Электрические скаты | 2 | 12 | 65 | 2 | 9 | У электрических скатов на дисках грудных плавников имеется орган, генерирующий электрический ток. С его помощью они обездвиживают жертву и обороняются. Силы тока достаточно, чтобы оглушить человека, древние греки и римляне использовали этих рыб для лечения болезней, например, от головной боли[8] | ||

| Rajiformes |

|

Скатообразные или ромботелые скаты | 1 | ? | ? | 4 | 12 | 26 | К Rajiformes относятся ромбовые скаты. Они отличаются наличием сильно увеличенных грудных плавников, которые выдаются вперёд по обе стороны головы, при уплощённом теле. Они плавают, совершая волнообразные движения грудными плавниками. Глаза и брызгальца расположены на дорсальной поверхности тела, а жаберные щели на вентральной. У них плоские зубы, приспособленные для дробления добычи, в целом эти рыбы являются плотоядными. Большинство видов размножается живорождением, хотя некоторые откладывают яйца, заключённые в защитную капсулу. | |

| Pristiformes |

|

Пилорылообразные | 4 | ? | ? | 3-5 | 2 |

Многие виды пилорыбообразных являются вымирающими или находятся на грани исчезновения[9] Пилорылообразные скаты похожи на акул, они плавают с помощью хвостового плавника, грудные плавники у них меньше по сравнению с прочими скатами. Грудные плавники соединяются с телом над жаберными плавниками, как и у остальных скатов, из-за чего их голова кажется очень широкой. У них имеется длинное, вытянутое и плоское рыло с выступающими латеральными зубцами. Длина рыла может достигать 1,8 м, а ширина 30 см. С его помощью пилорылообразные скаты бьют и протыкают небольших рыб, а также роются в грязи в поисках зарывшейся добычи. Пилорылообразные могут заплывать в пресноводные реки и озёра. Некоторые виды достигают 6 м в длину. |

||

| Myliobatiformes |

|

Хвостоколообразные | 10 | 29 | 221 | 1 | 16 | 33 | К Myliobatiformes относятся хвостоколы, скаты-бабочки, орляки и манты. Раньше их включали в отряд Rajiformes, однако филогенетические исследования показали, что они представляют собой монофилетическую группу[10]. |

| Филогенетическое дерево скатов[11] |

Выделяют следующие современные семейства скатов[12]:

- Отряд Torpediniformes — Электрические скаты, или гнюсообразные

- Семейство Torpedinidae — Гнюсовые

- Семейство Narcinidae — Нарциновые

- Отряд Rajiformes — Скатообразные, или ромботелые скаты

- Cемейство Rajidae — Ромбовые скаты

- Отряд Pristiformes — Пилорылообразные

- Cемейство Rhinobatidae — Рохлевые скаты, или гитарниковые

- Cемейство Rhinidae

- Cемейство Rhynchobatidae — Акулохвостые

- Семейство Pristidae — Пилорылые скаты

- Отряд Myliobatiformes — Хвостоколообразные

- Cемейство Platyrhinidae — Платириновые, или дисковые скаты

- Cемейство Zanobatidae — Занобатовые

- Cемейство Plesiobatidae — Плезиобатовые

- Cемейство Urolophidae — Короткохвостые хвостоколы

- Cемейство Hexatrygonidae — Шестижаберные скаты

- Cемейство Dasyatididae — Хвостоколовые

- Cемейство Potamotrygonidae — Речные хвостоколы

- Cемейство Gymnuridae — Гимнуровые

- Cемейство Urotrygonidae — Толстохвостые скаты

- Cемейство Myliobatidae — Орляковые скаты

Различия между акулами и скатами

| Сравнение акул, рохлевых скатов и скатов | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Характеристика | Акулы | Рохлевые скаты | Скаты |

| Форма | Веретенообразная, сжатая латерально | Диск, сжатый дорсовентрально (уплощённый) | Диск, сжатый дорсовентрально (уплощённый) |

| Брызгальца | Имеются не у всех видов | Имеются у всех видов. Развиты лучше, чем у акул[3]. | |

| Среда обитания | как правило, кормятся в пелагиали у поверхности воды, хотя есть донные виды | существуют как пелагические, так и донные виды | обычно кормятся у дна |

| Глаза | Обычно расположены на голове латерально. Глазное яблоко не прирощено к орбите. Мигательная перепонка имеется не у всех видов. | Обычно расположены на голове дорсально | Обычно расположены на голове дорсально. Глазное яблоко прирощено к орбите. Мигательная перепонка отсутствует[3] |

| Жаберные щели | Расположены латерально | Расположены вентрально | |

| Зубы | Как правило, острые и лезвиевидные, однако у некоторых видов имеют вид тёрки | Шипообразной формы, сильно уплощены и закруглены[3] | |

| Грудные плавники | Заметно выражены | Не выражены | Не выражены |

| Хвост | Крупный хвостовой плавник, который служит для продвижения вперёд | хвостовой плавник может использоваться для продвижения вперёд | форма варьируется от толстого хвоста, являющегося продолжением тела, до тонкого «хлыста» сходящего на нет |

| Анальный плавник | Как правило имеется, но у некоторых видов отсутствует | Отсутствует. | |

| Характер движения | плавают, двигая хвостовым плавником из стороны в сторону | у рохлевых и пилорылых скатов хвостовой плавник подобен акульему | плавают, взмахивая грудными плавниками как крыльями |

|

|

|

Взаимодействие с человеком

Использование

Приготовленные крылья ската

- В кулинарии

Крылья скатов являются деликатесом в португальской кухне. В Корее скатов едят в виде хве (сырыми): блюдо с ними называется «хонъохве чхомучхим» (кор. 홍어회 초무침), это «региональная специализация» южнокорейской провинции Чолладо.

- В промышленности

Кожа скатов долговечна и имеет необычную фактуру, применяется в кожевенной промышленности для изготовления кошельков, ремней, сумок, портфелей и т. п. Рукоятки японских мечей катан обтягивались кожей скатов.

- В научных исследованиях

- Содержание скатов в неволе

Опасность для человека

Некоторые виды скатов представляют опасность для людей. Силы электрического тока, генерируемого электрическими скатами, достаточно, чтобы оглушить человека, а хвостоколы способны наносить болезненные раны. В некоторых случаях они могут быть опасны для жизни, — так скат-хвостокол своим ядовитым жалом убил известного натуралиста, «охотника на крокодилов» Стива Ирвина.

Охранный статус

Все виды пилорылообразных скатов являются вымирающими или находятся на грани исчезновения.

Комментарии

- ↑ В некоторых классификациях данной группе присваивают систематический ранг «подотдел» (см. Нельсон, 2009, с. 129) либо «отдел» (см. Nelson, Grande, Wilson, 2016, с. 80)

Примечания

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nelson J. S., Grande T. C., Wilson M. V. H. Fishes of the World. 5th ed. — Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2016. — P. 80—82. — 752 p. — ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6. — DOI:10.1002/9781119174844.

- ↑ Нельсон Д. С. Рыбы мировой фауны / Пер. 4-го перераб. англ. изд. Н. Г. Богуцкой, науч. ред-ры А. М. Насека, А. С. Герд. — М.: Книжный дом «ЛИБРОКОМ», 2009. — С. 129—132. — ISBN 978-5-397-00675-0.

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 Жизнь животных. Том 4. Ланцетники. Круглоротые. Хрящевые рыбы. Костные рыбы / под ред. Т. С. Расса, гл. ред. В. Е. Соколов. — 2-е изд. — М.: Просвещение, 1983. — С. 575. — 300 000 экз.

- ↑ 1 2 Иванов, 2003, с. 49.

- ↑ Иванов, 2003, с. 37.

- ↑ Ильмаст Н. В. Введение в ихтиологию. — Петрозаводск: Карельский научный центр РАН, 2005. — С. 70—72. — ISBN 5-9274-0196-1.

- ↑ Douady C. J., Dosay M., Shivji M. S., Stanhope M. J. Molecular phylogenetic evidence refuting the hypothesis of Batoidea (rays and skates) as derived sharks (англ.) // Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. — 2003. — Vol. 26, no. 2. — P. 215—216. — PMID 12565032.

- ↑ Bullock, Theodore Holmes; Hopkins, Carl D.; Popper, Arthur N.; Fay, Richard R. Electroreception. — Springer, 2005. — С. 5—7. — ISBN 0-387-23192-7.

- ↑ Faria V. V., McDavitt M. T., Charvet P., Wiley T. R., Simpfendorfer C. A. and Naylor G. J. P. Species delineation and global population structure of Critically Endangered sawfishes (Pristidae) (англ.) // Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. — 2013. — Vol. 167, no. 1. — P. 136—164. — DOI:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2012.00872.x.

- ↑ Nelson J. S. Fishes of the World. — 2006. — С. 69—82. — ISBN 0-471-25031-7.

- ↑ Nelson, Grande, Wilson, 2016, p. 81.

- ↑ Nelson, Grande, Wilson, 2016, p. 81—93.

Литература

- А. А. Иванов. Физиология рыб / Под ред. С. Н. Шестах. — М.: Мир, 2003. — 284 с. — (Учебники и учебные пособия для студентов высших учебных заведений). — 5000 экз. — ISBN 5-03-003564-8.

- Nelson J. S., Grande T. C., Wilson M. V. H. Division Batomorphi—rays // Fishes of the World. 5th ed. — Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2016. — P. 80—95. — 752 p. — ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6. — DOI:10.1002/9781119174844.

Ссылки

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Stingrays

Temporal range: Early Cretaceous – Recent[1] PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Southern stingray (Hypanus americanus) | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Myliobatiformes |

| Suborder: | Myliobatoidei |

| Families | |

|

Stingrays are a group of sea rays, which are cartilaginous fish related to sharks. They are classified in the suborder Myliobatoidei of the order Myliobatiformes and consist of eight families: Hexatrygonidae (sixgill stingray), Plesiobatidae (deepwater stingray), Urolophidae (stingarees), Urotrygonidae (round rays), Dasyatidae (whiptail stingrays), Potamotrygonidae (river stingrays), Gymnuridae (butterfly rays) and Myliobatidae (eagle rays).[1][2]

There are about 220 known stingray species organized into 29 genera.

Stingrays are common in coastal tropical and subtropical marine waters throughout the world. Some species, such as the thorntail stingray (Dasyatis thetidis), are found in warmer temperate oceans and others, such as the deepwater stingray (Plesiobatis daviesi), are found in the deep ocean. The river stingrays and a number of whiptail stingrays (such as the Niger stingray (Fontitrygon garouaensis)) are restricted to fresh water. Most myliobatoids are demersal (inhabiting the next-to-lowest zone in the water column), but some, such as the pelagic stingray and the eagle rays, are pelagic.[3]

Stingray species are progressively becoming threatened or vulnerable to extinction, particularly as the consequence of unregulated fishing.[4] As of 2013, 45 species have been listed as vulnerable or endangered by the IUCN. The status of some other species is poorly known, leading to their being listed as data deficient.[5]

Anatomy

dorsal (topside) ← → ventral (underside)

External anatomy of a male bluntnose stingray (Hypanus say)

Jaw and teeth

The mouth of the stingray is located on the ventral side of the vertebrate. Stingrays exhibit hyostylic jaw suspension, which means that the mandibular arch is only suspended by an articulation with the hyomandibula. This type of suspensions allows for the upper jaw to have high mobility and protrude outward.[6] The teeth are modified placoid scales that are regularly shed and replaced.[7] In general, the teeth have a root implanted within the connective tissue and a visible portion of the tooth, is large and flat, allowing them to crush the bodies of hard shelled prey.[8] Male stingrays display sexual dimorphism by developing cusps, or pointed ends, to some of their teeth. During mating season, some stingray species fully change their tooth morphology which then returns to baseline during non-mating seasons.[9]

Spiracles

Spiracles are small openings that allow some fish and amphibians to breathe. Stingray spiracles are openings just behind its eyes. The respiratory system of stingrays is complicated by having two separate ways to take in water to use the oxygen. Most of the time stingrays take in water using their mouth and then send the water through the gills for gas exchange. This is efficient, but the mouth cannot be used when hunting because the stingrays bury themselves in the ocean sediment and wait for prey to swim by.[10] So the stingray switches to using its spiracles. With the spiracles, they can draw water free from sediment directly into their gills for gas exchange.[11] These alternate ventilation organs are less efficient than the mouth, since spiracles are unable to pull the same volume of water. However, it is enough when the stingray is quietly waiting to ambush its prey.

The flattened bodies of stingrays allow them to effectively conceal themselves in their environments. Stingrays do this by agitating the sand and hiding beneath it. Because their eyes are on top of their bodies and their mouths on the undersides, stingrays cannot see their prey after capture; instead, they use smell and electroreceptors (ampullae of Lorenzini) similar to those of sharks.[12] Stingrays settle on the bottom while feeding, often leaving only their eyes and tails visible. Coral reefs are favorite feeding grounds and are usually shared with sharks during high tide.[13]

Behavior

Reproduction

Mobula (devil rays) are thought to breach as a form of courtship.

During the breeding season, males of various stingray species such as the round stingray (Urobatis halleri), may rely on their ampullae of Lorenzini to sense certain electrical signals given off by mature females before potential copulation.[14] When a male is courting a female, he follows her closely, biting at her pectoral disc. He then places one of his two claspers into her valve.[15]

Reproductive ray behaviors are associated with their behavioral endocrinology, for example, in species such as the atlantic stingray (Hypanus sabinus), social groups are formed first, then the sexes display complex courtship behaviors that end in pair copulation which is similar to the species Urobatis halleri.[16] Furthermore, their mating period is one of the longest recorded in elasmobranch fish. Individuals are known to mate for seven months before the females ovulate in March. During this time, the male stingrays experience increased levels of androgen hormones which has been linked to its prolonged mating periods.[16] The behavior expressed among males and females during specific parts of this period involves aggressive social interactions.[16] Frequently, the males trail females with their snout near the female vent then proceed to bite the female on her fins and her body.[16] Although this mating behavior is similar to the species Urobatis halleri, differences can be seen in the particular actions of Hypanus sabinus. Seasonal elevated levels of serum androgens coincide with the expressed aggressive behavior, which led to the proposal that androgen steroids start, indorse and maintain aggressive sexual behaviors in the male rays for this species which drives the prolonged mating season. Similarly, concise elevations of serum androgens in females has been connected to increased aggression and improvement in mate choice. When their androgen steroid levels are elevated, they are able to improve their mate choice by quickly fleeing from tenacious males when undergoing ovulation succeeding impregnation. This ability affects the paternity of their offspring by refusing less qualified mates.[16]

Stingrays are ovoviviparous, bearing live young in «litters» of five to thirteen. During this period, the female’s behavior transitions to support of her future offspring. Females hold the embryos in the womb without a placenta. Instead, the embryos absorb nutrients from a yolk sac and after the sac is depleted, the mother provides uterine «milk».[17] After birth, the offspring generally disassociate from the mother and swim away, having been born with the instinctual abilities to protect and feed themselves. In a very small number of species, like the giant freshwater stingray (Urogymnus polylepis), the mother «cares» for her young by having them swim with her until they are one-third of her size.[18]

At the Sea Life London Aquarium, two female stingrays delivered seven baby stingrays, although the mothers have not been near a male for two years. This suggests some species of rays can store sperm then give birth when they deem conditions to be suitable.[19]

Locomotion

The stingray uses its paired pectoral fins for moving around. This is in contrast to sharks and most other fish, which get most of their swimming power from a single caudal (tail) fin.[20][21] Stingray pectoral fin locomotion can be divided into two categories, undulatory and oscillatory.[22] Stingrays who use undulatory locomotion have shorter thicker fins for slower motile movements in benthic areas.[23] Longer thinner pectoral fins make for faster speeds in oscillation mobility in pelagic zones.[22] Visually distinguishable oscillation has less than one wave going, opposed to undulation having more than one wave at all times.[22]

Feeding behavior and diet

Bat ray (Myliobatis californica) in a feeding posture

Stingrays use a wide range of feeding strategies. Some have specialized jaws that allow them to crush hard mollusk shells,[24] whereas others use external mouth structures called cephalic lobes to guide plankton into their oral cavity.[25] Benthic stingrays (those that reside on the sea floor) are ambush hunters.[26] They wait until prey comes near, then use a strategy called «tenting».[27] With pectoral fins pressed against the substrate, the ray will raise its head, generating a suction force that pulls the prey underneath the body. This form of whole-body suction is analogous to the buccal suction feeding performed by ray-finned fish. Stingrays exhibit a wide range of colors and patterns on their dorsal surface to help them camouflage with the sandy bottom. Some stingrays can even change color over the course of several days to adjust to new habitats. Since their mouths are on the side of their bodies, they catch their prey, then crush and eat with their powerful jaws. Like its shark relatives, the stingray is outfitted with electrical sensors called ampullae of Lorenzini. Located around the stingray’s mouth, these organs sense the natural electrical charges of potential prey. Many rays have jaw teeth to enable them to crush mollusks such as clams, oysters and mussels.

Most stingrays feed primarily on mollusks, crustaceans and, occasionally, on small fish. Freshwater stingrays in the Amazon feed on insects and break down their tough exoskeletons with mammal-like chewing motions.[28] Large pelagic rays like the Manta use ram feeding to consume vast quantities of plankton and have been seen swimming in acrobatic patterns through plankton patches.[29]

Stingray injuries

The stinger of a stingray is known also as the spinal blade. It is located in the mid-area of the tail and can secrete venom. The ruler measures 10cm.

Stingrays are not usually aggressive and ordinarily attack humans only when provoked, such as when they are accidentally stepped on.[30] Stingrays can have one, two or three blades. Contact with the spinal blade or blades causes local trauma (from the cut itself), pain, swelling, muscle cramps from the venom and, later, may result in infection from bacteria or fungi.[31] The injury is very painful, but rarely life-threatening unless the stinger pierces a vital area.[30] The blade is frequently barbed and usually breaks off in the wound. Surgery may be required to remove the fragments.[32]

Fatal stings are very rare.[30] The death of Steve Irwin in 2006 was only the second recorded in Australian waters since 1945.[33] The stinger penetrated his thoracic wall and pierced his heart, causing massive trauma and bleeding.[34]

Venom

Posterior anatomy of a stingray. (1) Pelvic Fins (2) Caudal Tubercles (3) Stinger (4) Dorsal Fin (5) Claspers (6) Tail

The venom of the stingray has been relatively unstudied due to the mixture of venomous tissue secretions cells and mucous membrane cell products that occurs upon secretion from the spinal blade. The spine is covered with the epidermal skin layer. During secretion, the venom penetrates the epidermis and mixes with the mucus to release the venom on its victim. Typically, other venomous organisms create and store their venom in a gland. The stingray is notable in that it stores its venom within tissue cells. The toxins that have been confirmed to be within the venom are cystatins, peroxiredoxin and galectin.[35] Galectin induces cell death in its victims and cystatins inhibit defense enzymes. In humans, these toxins lead to increased blood flow in the superficial capillaries and cell death.[36] Despite the number of cells and toxins that are within the stingray, there is little relative energy required to produce and store the venom.

The venom is produced and stored in the secretory cells of the vertebral column at the mid-distal region. These secretory cells are housed within the ventrolateral grooves of the spine. The cells of both marine and freshwater stingrays are round and contain a great amount of granule-filled cytoplasm.[37] The stinging cells of marine stingrays are located only within these lateral grooves of the stinger.[38] The stinging cells of freshwater stingray branch out beyond the lateral grooves to cover a larger surface area along the entire blade. Due to this large area and an increased number of proteins within the cells, the venom of freshwater stingrays has a greater toxicity than that of marine stingrays.[37]

Human use

As food

Dried strips of stingray meat served as food in Japan

Rays are edible, and may be caught as food using fishing lines or spears. Stingray recipes can be found in many coastal areas worldwide.[39] For example, in Malaysia and Singapore, stingray is commonly grilled over charcoal, then served with spicy sambal sauce. In Goa, and other Indian states, it is sometimes used as part of spicy curries. Generally, the most prized parts of the stingray are the wings, the «cheek» (the area surrounding the eyes), and the liver. The rest of the ray is considered too rubbery to have any culinary uses.[40]

Ecotourism

Stingrays are usually very docile and curious, their usual reaction being to flee any disturbance, but they sometimes brush their fins past any new object they encounter. Nevertheless, certain larger species may be more aggressive and should be approached with caution, as the stingray’s defensive reflex (use of its venomous stinger) may result in serious injury or death.[41]

Other uses

The skin of the ray is used as an under layer for the cord or leather wrap (known as samegawa in Japanese) on Japanese swords due to its hard, rough texture that keeps the braided wrap from sliding on the handle during use.[42]

Several ethnological sections in museums,[43] such as the British Museum, display arrowheads and spearheads made of stingray stingers, used in Micronesia and elsewhere.[44] Henry de Monfreid stated in his books that before World War II, in the Horn of Africa, whips were made from the tails of big stingrays and these devices inflicted cruel cuts, so in Aden, the British forbade their use on women and slaves. In former Spanish colonies, a stingray is called raya látigo («whip ray»).

Some stingray species are commonly seen in public aquarium exhibits and more recently in home aquaria.[39][45]

Fossils

Batoids (rays) belong to the ancient lineage of cartilaginous fishes. Fossil denticles (tooth-like scales in the skin) resembling those of today’s chondrichthyans date at least as far back as the Ordovician, with the oldest unambiguous fossils of cartilaginous fish dating from the middle Devonian. A clade within this diverse family, the Neoselachii, emerged by the Triassic, with the best-understood neoselachian fossils dating from the Jurassic. The clade is represented today by sharks, sawfish, rays and skates.[46]

Although stingray teeth are rare on sea bottoms compared to the similar shark teeth, scuba divers searching for the latter do encounter the teeth of stingrays. Permineralized stingray teeth have been found in sedimentary deposits around the world, including fossiliferous outcrops in Morocco.[47]

Gallery

See also

- List of threatened rays

References

- ^ a b Nelson JS (2006). Fishes of the World (fourth ed.). John Wiley. pp. 76–82. ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- ^ Helfman GS, Collette BB, Facey DE (1997). The Diversity of Fishes. Blackwell Science. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-86542-256-8.

- ^ Bester C, Mollett HF, Bourdon J (2017-05-09). «Pelagic Stingray». Florida Museum of Natural History, Ichthyology department. Archived from the original on 2016-01-15. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- ^ The Future of Sharks: A Review of Action and Inaction Archived 2013-05-12 at the Wayback Machine CITES AC25 Inf. 6, 2011.

- ^ «IUCN Red List». International Union for Conservation of Nature. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014.

- ^ Carrier JC, Musick JA, Heithaus MR (2012-04-09). Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives (Second ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 9781439839263. Archived from the original on 2022-01-10. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ Khanna, D. R. (2004). Biology Of Fishes. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 9788171419081. Archived from the original on 2022-01-10. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ Kolmann, M. A.; Crofts, S. B.; Dean, M. N.; Summers, A. P.; Lovejoy, N. R. (13 November 2015). «Morphology does not predict performance: jaw curvature and prey crushing in durophagous stingrays». Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (24): 3941–3949. doi:10.1242/jeb.127340. PMID 26567348.

- ^ Kajiura, null; Tricas, null (1996). «Seasonal dynamics of dental sexual dimorphism in the Atlantic stingray Dasyatis sabina». The Journal of Experimental Biology. 199 (Pt 10): 2297–2306. doi:10.1242/jeb.199.10.2297. PMID 9320215.

- ^ «Stingray». bioweb.uwlax.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- ^ Kardong K (2015). Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-07-802302-6.

- ^ Bedore CN, Harris LL, Kajiura SM (April 2014). «Behavioral responses of batoid elasmobranchs to prey-simulating electric fields are correlated to peripheral sensory morphology and ecology». Zoology. 117 (2): 95–103. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2013.09.002. PMID 24290363.

- ^ «Stingray City — Altering Stingray Behavior & Physiology?». DivePhotoGuide. Retrieved 2023-02-14.

- ^ Tricas TC, Michael SW, Sisneros JA (December 1995). «Electrosensory optimization to conspecific phasic signals for mating». Neuroscience Letters. 202 (1–2): 129–32. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(95)12230-3. PMID 8787848. S2CID 42318841.

- ^ FAQs on Freshwater Stingray Behavior Archived 2017-10-02 at the Wayback Machine. Wetwebmedia.com. Retrieved on 2012-07-17.

- ^ a b c d e Tricas, Timothy C.; Rasmussen, L. E. L.; Maruska, Karen P. (2000). «Annual Cycles of Steroid Hormone Production, Gonad Development, and Reproductive Behavior in the Atlantic Stingray». General and Comparative Endocrinology. 118 (2): 209–25. doi:10.1006/gcen.2000.7466. PMID 10890563. S2CID 11150958. Archived from the original on 2023-01-24. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- ^ Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department: Atlantic Stingray Archived 2016-01-04 at the Wayback Machine. Flmnh.ufl.edu. Retrieved on 2012-07-17.

- ^ Seubert, Curtis (April 24, 2017). «How Do Stingrays Take Care of Their Young?». Sciencing. Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ «Stingrays born in female only tank». The Sydney Morning Herald. 2011-08-10. Archived from the original on 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- ^ Wang, Y (2015). «Design and Experiment on Biometic Robotic Fish Inspired by Freshwater Stingray». Journal of Bionic Engineering. 12 (2): 204–216. doi:10.1016/S1672-6529(14)60113-X. S2CID 136537698.

- ^ Macesic, J (2013). «Synchronized swimming: coordination of pelvic and pectoral fins during augmented punting by freshwater stingray Potamotrygon orbignyi«. Zoology. 116 (3): 144–150. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2012.11.002. PMID 23477972.

- ^ a b c Fontanella J (2013). «Two- and three-dimensional geometries of batoids in relation to locomotor mode». Journal of Experimental Biology and Ecology. 446: 273–281. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2013.05.016.

- ^ Bottom II, R (2016). «Hydrodynamics of swimming in stingrays: numerical simulations and the role of the leading-edge vortex» (PDF). Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 788: 407–443. Bibcode:2016JFM…788..407B. doi:10.1017/jfm.2015.702. S2CID 124395779. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-15.

- ^ Kolmann MA, Huber DR, Motta PJ, Grubbs RD (September 2015). «Feeding biomechanics of the cownose ray, Rhinoptera bonasus, over ontogeny». Journal of Anatomy. 227 (3): 341–51. doi:10.1111/joa.12342. PMC 4560568. PMID 26183820.

- ^ Dean MN, Bizzarro JJ, Summers AP (July 2007). «The evolution of cranial design, diet, and feeding mechanisms in batoid fishes». Integrative and Comparative Biology. 47 (1): 70–81. doi:10.1093/icb/icm034. PMID 21672821.

- ^ Curio E (1976). The Ethology of Predation — Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-81028-2. ISBN 978-3-642-81030-5. S2CID 8090692.

- ^ Wilga CD, Maia A, Nauwelaerts S, Lauder GV (February 2012). «Prey handling using whole-body fluid dynamics in batoids». Zoology. 115 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2011.09.002. PMID 22244456.

- ^ Kolmann MA, Welch KC, Summers AP, Lovejoy NR (September 2016). «Always chew your food: freshwater stingrays use mastication to process tough insect prey». Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 283 (1838): 20161392. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.1392. PMC 5031661. PMID 27629029.

- ^ Notarbartolo-di-Sciara G, Hillyer EV (1989-01-01). «Mobulid Rays off Eastern Venezuela (Chondrichthyes, Mobulidae)». Copeia. 1989 (3): 607–614. doi:10.2307/1445487. JSTOR 1445487.

- ^ a b c Slaughter RJ, Beasley DM, Lambie BS, Schep LJ (February 2009). «New Zealand’s venomous creatures». The New Zealand Medical Journal. 122 (1290): 83–97. PMID 19319171. Archived from the original on April 17, 2011.

- ^ «Stingray Injury Case Reports». Clinical Toxicology Resources. University of Adelaide. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2012.

- ^ Flint DJ, Sugrue WJ (April 1999). «Stingray injuries: a lesson in debridement». The New Zealand Medical Journal. 112 (1086): 137–8. PMID 10340692.

- ^ Hadhazy, Adam T. (2006-09-11). «I thought stingrays were harmless, so how did one manage to kill the «Crocodile Hunter?»«. Scienceline. Archived from the original on 2022-03-29. Retrieved 2018-11-18.

- ^ Discovery Channel Mourns the Death of Steve Irwin Archived 2013-01-07 at the Wayback Machine. animal.discovery.com

- ^ da Silva NJ, Ferreira KR, Pinto RN, Aird SD (June 2015). «A Severe Accident Caused by an Ocellate River Stingray (Potamotrygon motoro) in Central Brazil: How Well Do We Really Understand Stingray Venom Chemistry, Envenomation, and Therapeutics?». Toxins. 7 (6): 2272–88. doi:10.3390/toxins7062272. PMC 4488702. PMID 26094699.

- ^ Dos Santos JC, Grund LZ, Seibert CS, Marques EE, Soares AB, Quesniaux VF, Ryffel B, Lopes-Ferreira M, Lima C (August 2017). «Stingray venom activates IL-33 producing cardiomyocytes, but not mast cell, to promote acute neutrophil-mediated injury». Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 7912. Bibcode:2017NatSR…7.7912D. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08395-y. PMC 5554156. PMID 28801624.

- ^ a b Pedroso CM, Jared C, Charvet-Almeida P, Almeida MP, Garrone Neto D, Lira MS, Haddad V, Barbaro KC, Antoniazzi MM (October 2007). «Morphological characterization of the venom secretory epidermal cells in the stinger of marine and freshwater stingrays». Toxicon. 50 (5): 688–97. doi:10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.06.004. PMID 17659760.

- ^ Enzor LA, Wilborn RE, Bennett WA (December 2011). «Toxicity and metabolic costs of the Atlantic stingray (Dasyatis sabina) venom delivery system in relation to its role in life history». Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 409 (1–2): 235–239. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2011.08.026.

- ^ a b «Animal Diversity Web – Dasyatidae, Stingrays». Animal Diversity Web. 2021-03-10. Archived from the original on 2021-06-17. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ^ «The Delicious and Deadly Stingray. Nyonya. New York, NY. (Partially from the Archives.)». Retrieved 2023-02-14.

- ^ Sullivan BN (May 2009). «Stingrays: Dangerous or Not?». The Right Blue. Archived from the original on 24 July 2012. Retrieved 17 July 2012.

- ^ «The Samegawa – Parts of a Japanese Katana». Reliks. Archived from the original on 2021-02-26. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ^ FLMNH Ichthyology Department: Daisy Stingray Archived 2016-01-04 at the Wayback Machine. Flmnh.ufl.edu. Retrieved on 17 July 2012.

- ^ Dasyatis rudis (Smalltooth Stingray)[permanent dead link]. Iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 17 July 2012.

- ^ Michael, Scott W. (September 2014). «Rays in the Home Aquarium». Tropical Fish Magazine. Archived from the original on 2021-04-22. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- ^ «Fossil Record of the Chondrichthyes». ucmp.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 2023-02-14.

- ^ «Heliobatis radians Stingray Fossil from Green River». www.fossilmall.com. Retrieved 2023-02-14.

Bibliography

- Froese, Rainer, and Daniel Pauly, eds. (2005). «Dasyatidae» in FishBase. August 2005 version.

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Stingray.

- «Beware the Ugly Sting Ray.» Popular Science, July 1954, pp. 117–118/pp. 224–228.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Stingrays

Temporal range: Early Cretaceous – Recent[1] PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Southern stingray (Hypanus americanus) | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Myliobatiformes |

| Suborder: | Myliobatoidei |

| Families | |

|

Stingrays are a group of sea rays, which are cartilaginous fish related to sharks. They are classified in the suborder Myliobatoidei of the order Myliobatiformes and consist of eight families: Hexatrygonidae (sixgill stingray), Plesiobatidae (deepwater stingray), Urolophidae (stingarees), Urotrygonidae (round rays), Dasyatidae (whiptail stingrays), Potamotrygonidae (river stingrays), Gymnuridae (butterfly rays) and Myliobatidae (eagle rays).[1][2]

There are about 220 known stingray species organized into 29 genera.

Stingrays are common in coastal tropical and subtropical marine waters throughout the world. Some species, such as the thorntail stingray (Dasyatis thetidis), are found in warmer temperate oceans and others, such as the deepwater stingray (Plesiobatis daviesi), are found in the deep ocean. The river stingrays and a number of whiptail stingrays (such as the Niger stingray (Fontitrygon garouaensis)) are restricted to fresh water. Most myliobatoids are demersal (inhabiting the next-to-lowest zone in the water column), but some, such as the pelagic stingray and the eagle rays, are pelagic.[3]

Stingray species are progressively becoming threatened or vulnerable to extinction, particularly as the consequence of unregulated fishing.[4] As of 2013, 45 species have been listed as vulnerable or endangered by the IUCN. The status of some other species is poorly known, leading to their being listed as data deficient.[5]

Anatomy

dorsal (topside) ← → ventral (underside)

External anatomy of a male bluntnose stingray (Hypanus say)

Jaw and teeth

The mouth of the stingray is located on the ventral side of the vertebrate. Stingrays exhibit hyostylic jaw suspension, which means that the mandibular arch is only suspended by an articulation with the hyomandibula. This type of suspensions allows for the upper jaw to have high mobility and protrude outward.[6] The teeth are modified placoid scales that are regularly shed and replaced.[7] In general, the teeth have a root implanted within the connective tissue and a visible portion of the tooth, is large and flat, allowing them to crush the bodies of hard shelled prey.[8] Male stingrays display sexual dimorphism by developing cusps, or pointed ends, to some of their teeth. During mating season, some stingray species fully change their tooth morphology which then returns to baseline during non-mating seasons.[9]

Spiracles

Spiracles are small openings that allow some fish and amphibians to breathe. Stingray spiracles are openings just behind its eyes. The respiratory system of stingrays is complicated by having two separate ways to take in water to use the oxygen. Most of the time stingrays take in water using their mouth and then send the water through the gills for gas exchange. This is efficient, but the mouth cannot be used when hunting because the stingrays bury themselves in the ocean sediment and wait for prey to swim by.[10] So the stingray switches to using its spiracles. With the spiracles, they can draw water free from sediment directly into their gills for gas exchange.[11] These alternate ventilation organs are less efficient than the mouth, since spiracles are unable to pull the same volume of water. However, it is enough when the stingray is quietly waiting to ambush its prey.

The flattened bodies of stingrays allow them to effectively conceal themselves in their environments. Stingrays do this by agitating the sand and hiding beneath it. Because their eyes are on top of their bodies and their mouths on the undersides, stingrays cannot see their prey after capture; instead, they use smell and electroreceptors (ampullae of Lorenzini) similar to those of sharks.[12] Stingrays settle on the bottom while feeding, often leaving only their eyes and tails visible. Coral reefs are favorite feeding grounds and are usually shared with sharks during high tide.[13]

Behavior

Reproduction

Mobula (devil rays) are thought to breach as a form of courtship.

During the breeding season, males of various stingray species such as the round stingray (Urobatis halleri), may rely on their ampullae of Lorenzini to sense certain electrical signals given off by mature females before potential copulation.[14] When a male is courting a female, he follows her closely, biting at her pectoral disc. He then places one of his two claspers into her valve.[15]

Reproductive ray behaviors are associated with their behavioral endocrinology, for example, in species such as the atlantic stingray (Hypanus sabinus), social groups are formed first, then the sexes display complex courtship behaviors that end in pair copulation which is similar to the species Urobatis halleri.[16] Furthermore, their mating period is one of the longest recorded in elasmobranch fish. Individuals are known to mate for seven months before the females ovulate in March. During this time, the male stingrays experience increased levels of androgen hormones which has been linked to its prolonged mating periods.[16] The behavior expressed among males and females during specific parts of this period involves aggressive social interactions.[16] Frequently, the males trail females with their snout near the female vent then proceed to bite the female on her fins and her body.[16] Although this mating behavior is similar to the species Urobatis halleri, differences can be seen in the particular actions of Hypanus sabinus. Seasonal elevated levels of serum androgens coincide with the expressed aggressive behavior, which led to the proposal that androgen steroids start, indorse and maintain aggressive sexual behaviors in the male rays for this species which drives the prolonged mating season. Similarly, concise elevations of serum androgens in females has been connected to increased aggression and improvement in mate choice. When their androgen steroid levels are elevated, they are able to improve their mate choice by quickly fleeing from tenacious males when undergoing ovulation succeeding impregnation. This ability affects the paternity of their offspring by refusing less qualified mates.[16]

Stingrays are ovoviviparous, bearing live young in «litters» of five to thirteen. During this period, the female’s behavior transitions to support of her future offspring. Females hold the embryos in the womb without a placenta. Instead, the embryos absorb nutrients from a yolk sac and after the sac is depleted, the mother provides uterine «milk».[17] After birth, the offspring generally disassociate from the mother and swim away, having been born with the instinctual abilities to protect and feed themselves. In a very small number of species, like the giant freshwater stingray (Urogymnus polylepis), the mother «cares» for her young by having them swim with her until they are one-third of her size.[18]

At the Sea Life London Aquarium, two female stingrays delivered seven baby stingrays, although the mothers have not been near a male for two years. This suggests some species of rays can store sperm then give birth when they deem conditions to be suitable.[19]

Locomotion

The stingray uses its paired pectoral fins for moving around. This is in contrast to sharks and most other fish, which get most of their swimming power from a single caudal (tail) fin.[20][21] Stingray pectoral fin locomotion can be divided into two categories, undulatory and oscillatory.[22] Stingrays who use undulatory locomotion have shorter thicker fins for slower motile movements in benthic areas.[23] Longer thinner pectoral fins make for faster speeds in oscillation mobility in pelagic zones.[22] Visually distinguishable oscillation has less than one wave going, opposed to undulation having more than one wave at all times.[22]

Feeding behavior and diet

Bat ray (Myliobatis californica) in a feeding posture

Stingrays use a wide range of feeding strategies. Some have specialized jaws that allow them to crush hard mollusk shells,[24] whereas others use external mouth structures called cephalic lobes to guide plankton into their oral cavity.[25] Benthic stingrays (those that reside on the sea floor) are ambush hunters.[26] They wait until prey comes near, then use a strategy called «tenting».[27] With pectoral fins pressed against the substrate, the ray will raise its head, generating a suction force that pulls the prey underneath the body. This form of whole-body suction is analogous to the buccal suction feeding performed by ray-finned fish. Stingrays exhibit a wide range of colors and patterns on their dorsal surface to help them camouflage with the sandy bottom. Some stingrays can even change color over the course of several days to adjust to new habitats. Since their mouths are on the side of their bodies, they catch their prey, then crush and eat with their powerful jaws. Like its shark relatives, the stingray is outfitted with electrical sensors called ampullae of Lorenzini. Located around the stingray’s mouth, these organs sense the natural electrical charges of potential prey. Many rays have jaw teeth to enable them to crush mollusks such as clams, oysters and mussels.

Most stingrays feed primarily on mollusks, crustaceans and, occasionally, on small fish. Freshwater stingrays in the Amazon feed on insects and break down their tough exoskeletons with mammal-like chewing motions.[28] Large pelagic rays like the Manta use ram feeding to consume vast quantities of plankton and have been seen swimming in acrobatic patterns through plankton patches.[29]

Stingray injuries

The stinger of a stingray is known also as the spinal blade. It is located in the mid-area of the tail and can secrete venom. The ruler measures 10cm.

Stingrays are not usually aggressive and ordinarily attack humans only when provoked, such as when they are accidentally stepped on.[30] Stingrays can have one, two or three blades. Contact with the spinal blade or blades causes local trauma (from the cut itself), pain, swelling, muscle cramps from the venom and, later, may result in infection from bacteria or fungi.[31] The injury is very painful, but rarely life-threatening unless the stinger pierces a vital area.[30] The blade is frequently barbed and usually breaks off in the wound. Surgery may be required to remove the fragments.[32]

Fatal stings are very rare.[30] The death of Steve Irwin in 2006 was only the second recorded in Australian waters since 1945.[33] The stinger penetrated his thoracic wall and pierced his heart, causing massive trauma and bleeding.[34]

Venom

Posterior anatomy of a stingray. (1) Pelvic Fins (2) Caudal Tubercles (3) Stinger (4) Dorsal Fin (5) Claspers (6) Tail

The venom of the stingray has been relatively unstudied due to the mixture of venomous tissue secretions cells and mucous membrane cell products that occurs upon secretion from the spinal blade. The spine is covered with the epidermal skin layer. During secretion, the venom penetrates the epidermis and mixes with the mucus to release the venom on its victim. Typically, other venomous organisms create and store their venom in a gland. The stingray is notable in that it stores its venom within tissue cells. The toxins that have been confirmed to be within the venom are cystatins, peroxiredoxin and galectin.[35] Galectin induces cell death in its victims and cystatins inhibit defense enzymes. In humans, these toxins lead to increased blood flow in the superficial capillaries and cell death.[36] Despite the number of cells and toxins that are within the stingray, there is little relative energy required to produce and store the venom.

The venom is produced and stored in the secretory cells of the vertebral column at the mid-distal region. These secretory cells are housed within the ventrolateral grooves of the spine. The cells of both marine and freshwater stingrays are round and contain a great amount of granule-filled cytoplasm.[37] The stinging cells of marine stingrays are located only within these lateral grooves of the stinger.[38] The stinging cells of freshwater stingray branch out beyond the lateral grooves to cover a larger surface area along the entire blade. Due to this large area and an increased number of proteins within the cells, the venom of freshwater stingrays has a greater toxicity than that of marine stingrays.[37]

Human use

As food

Dried strips of stingray meat served as food in Japan

Rays are edible, and may be caught as food using fishing lines or spears. Stingray recipes can be found in many coastal areas worldwide.[39] For example, in Malaysia and Singapore, stingray is commonly grilled over charcoal, then served with spicy sambal sauce. In Goa, and other Indian states, it is sometimes used as part of spicy curries. Generally, the most prized parts of the stingray are the wings, the «cheek» (the area surrounding the eyes), and the liver. The rest of the ray is considered too rubbery to have any culinary uses.[40]

Ecotourism

Stingrays are usually very docile and curious, their usual reaction being to flee any disturbance, but they sometimes brush their fins past any new object they encounter. Nevertheless, certain larger species may be more aggressive and should be approached with caution, as the stingray’s defensive reflex (use of its venomous stinger) may result in serious injury or death.[41]

Other uses

The skin of the ray is used as an under layer for the cord or leather wrap (known as samegawa in Japanese) on Japanese swords due to its hard, rough texture that keeps the braided wrap from sliding on the handle during use.[42]

Several ethnological sections in museums,[43] such as the British Museum, display arrowheads and spearheads made of stingray stingers, used in Micronesia and elsewhere.[44] Henry de Monfreid stated in his books that before World War II, in the Horn of Africa, whips were made from the tails of big stingrays and these devices inflicted cruel cuts, so in Aden, the British forbade their use on women and slaves. In former Spanish colonies, a stingray is called raya látigo («whip ray»).

Some stingray species are commonly seen in public aquarium exhibits and more recently in home aquaria.[39][45]

Fossils

Batoids (rays) belong to the ancient lineage of cartilaginous fishes. Fossil denticles (tooth-like scales in the skin) resembling those of today’s chondrichthyans date at least as far back as the Ordovician, with the oldest unambiguous fossils of cartilaginous fish dating from the middle Devonian. A clade within this diverse family, the Neoselachii, emerged by the Triassic, with the best-understood neoselachian fossils dating from the Jurassic. The clade is represented today by sharks, sawfish, rays and skates.[46]

Although stingray teeth are rare on sea bottoms compared to the similar shark teeth, scuba divers searching for the latter do encounter the teeth of stingrays. Permineralized stingray teeth have been found in sedimentary deposits around the world, including fossiliferous outcrops in Morocco.[47]

Gallery

See also

- List of threatened rays

References

- ^ a b Nelson JS (2006). Fishes of the World (fourth ed.). John Wiley. pp. 76–82. ISBN 978-0-471-25031-9.

- ^ Helfman GS, Collette BB, Facey DE (1997). The Diversity of Fishes. Blackwell Science. p. 180. ISBN 978-0-86542-256-8.

- ^ Bester C, Mollett HF, Bourdon J (2017-05-09). «Pelagic Stingray». Florida Museum of Natural History, Ichthyology department. Archived from the original on 2016-01-15. Retrieved 2009-09-29.

- ^ The Future of Sharks: A Review of Action and Inaction Archived 2013-05-12 at the Wayback Machine CITES AC25 Inf. 6, 2011.

- ^ «IUCN Red List». International Union for Conservation of Nature. Archived from the original on June 27, 2014.

- ^ Carrier JC, Musick JA, Heithaus MR (2012-04-09). Biology of Sharks and Their Relatives (Second ed.). CRC Press. ISBN 9781439839263. Archived from the original on 2022-01-10. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ Khanna, D. R. (2004). Biology Of Fishes. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 9788171419081. Archived from the original on 2022-01-10. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ Kolmann, M. A.; Crofts, S. B.; Dean, M. N.; Summers, A. P.; Lovejoy, N. R. (13 November 2015). «Morphology does not predict performance: jaw curvature and prey crushing in durophagous stingrays». Journal of Experimental Biology. 218 (24): 3941–3949. doi:10.1242/jeb.127340. PMID 26567348.

- ^ Kajiura, null; Tricas, null (1996). «Seasonal dynamics of dental sexual dimorphism in the Atlantic stingray Dasyatis sabina». The Journal of Experimental Biology. 199 (Pt 10): 2297–2306. doi:10.1242/jeb.199.10.2297. PMID 9320215.

- ^ «Stingray». bioweb.uwlax.edu. Archived from the original on 2018-07-23. Retrieved 2018-05-12.

- ^ Kardong K (2015). Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution. New York: McGraw-Hill Education. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-07-802302-6.

- ^ Bedore CN, Harris LL, Kajiura SM (April 2014). «Behavioral responses of batoid elasmobranchs to prey-simulating electric fields are correlated to peripheral sensory morphology and ecology». Zoology. 117 (2): 95–103. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2013.09.002. PMID 24290363.

- ^ «Stingray City — Altering Stingray Behavior & Physiology?». DivePhotoGuide. Retrieved 2023-02-14.

- ^ Tricas TC, Michael SW, Sisneros JA (December 1995). «Electrosensory optimization to conspecific phasic signals for mating». Neuroscience Letters. 202 (1–2): 129–32. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(95)12230-3. PMID 8787848. S2CID 42318841.

- ^ FAQs on Freshwater Stingray Behavior Archived 2017-10-02 at the Wayback Machine. Wetwebmedia.com. Retrieved on 2012-07-17.

- ^ a b c d e Tricas, Timothy C.; Rasmussen, L. E. L.; Maruska, Karen P. (2000). «Annual Cycles of Steroid Hormone Production, Gonad Development, and Reproductive Behavior in the Atlantic Stingray». General and Comparative Endocrinology. 118 (2): 209–25. doi:10.1006/gcen.2000.7466. PMID 10890563. S2CID 11150958. Archived from the original on 2023-01-24. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- ^ Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department: Atlantic Stingray Archived 2016-01-04 at the Wayback Machine. Flmnh.ufl.edu. Retrieved on 2012-07-17.

- ^ Seubert, Curtis (April 24, 2017). «How Do Stingrays Take Care of Their Young?». Sciencing. Archived from the original on December 16, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ «Stingrays born in female only tank». The Sydney Morning Herald. 2011-08-10. Archived from the original on 2020-07-25. Retrieved 2020-07-25.

- ^ Wang, Y (2015). «Design and Experiment on Biometic Robotic Fish Inspired by Freshwater Stingray». Journal of Bionic Engineering. 12 (2): 204–216. doi:10.1016/S1672-6529(14)60113-X. S2CID 136537698.

- ^ Macesic, J (2013). «Synchronized swimming: coordination of pelvic and pectoral fins during augmented punting by freshwater stingray Potamotrygon orbignyi«. Zoology. 116 (3): 144–150. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2012.11.002. PMID 23477972.

- ^ a b c Fontanella J (2013). «Two- and three-dimensional geometries of batoids in relation to locomotor mode». Journal of Experimental Biology and Ecology. 446: 273–281. doi:10.1016/j.jembe.2013.05.016.

- ^ Bottom II, R (2016). «Hydrodynamics of swimming in stingrays: numerical simulations and the role of the leading-edge vortex» (PDF). Journal of Fluid Mechanics. 788: 407–443. Bibcode:2016JFM…788..407B. doi:10.1017/jfm.2015.702. S2CID 124395779. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-15.

- ^ Kolmann MA, Huber DR, Motta PJ, Grubbs RD (September 2015). «Feeding biomechanics of the cownose ray, Rhinoptera bonasus, over ontogeny». Journal of Anatomy. 227 (3): 341–51. doi:10.1111/joa.12342. PMC 4560568. PMID 26183820.

- ^ Dean MN, Bizzarro JJ, Summers AP (July 2007). «The evolution of cranial design, diet, and feeding mechanisms in batoid fishes». Integrative and Comparative Biology. 47 (1): 70–81. doi:10.1093/icb/icm034. PMID 21672821.

- ^ Curio E (1976). The Ethology of Predation — Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-81028-2. ISBN 978-3-642-81030-5. S2CID 8090692.

- ^ Wilga CD, Maia A, Nauwelaerts S, Lauder GV (February 2012). «Prey handling using whole-body fluid dynamics in batoids». Zoology. 115 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2011.09.002. PMID 22244456.

- ^ Kolmann MA, Welch KC, Summers AP, Lovejoy NR (September 2016). «Always chew your food: freshwater stingrays use mastication to process tough insect prey». Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 283 (1838): 20161392. doi:10.1098/rspb.2016.1392. PMC 5031661. PMID 27629029.