В принципе можно писать как угодно, хоть «$цаентология», но если хотите, чтобы к вам ходили люди, надо писать «саентология«. Дело в том, что так перевели название своей секты российские саентологи, и всякий, столкнувшийся с ними и получивший их буклет, будет писать в поисковой строке слово «саентология«. Кроме того, Яндекс и Гугл уже считают вариант «сайентология» опечаткой и автоматически исправляют, уберая букву «й». Вариант «сайентология» ввел известный российский специалист по культам Александр Дворкин, считая такой перевод более правильным, и с его подачи этот вариант разошелся по различным критическим статьям и новостям. Но, на мой взгляд, лучше избегать такого написания по изложенным причинам и пользоваться терминологией саентологов: ОТ вместо ДТ, одитинг вместо аудитинга и т. д. Иначе получится так: материалов много, но найти их с помощью поисковика не представляется возможным.

Scientology is a set of beliefs and practices invented by the American author L. Ron Hubbard, and an associated movement. Adherents are called Scientologists. It has been variously defined as a cult, a business, or a new religious movement.[11] The primary exponent of Scientology is the Church of Scientology, a centralized and hierarchical organization based in Florida, although many practitioners exist independently of the Church, in what is called the Free Zone. Estimates put the number of Scientologists at under 40,000 worldwide.

Scientology texts say that a human possesses an immortal inner self, termed a thetan, that resides in the physical body and has experienced many past lives. Scientologists believe that traumatic events experienced by the thetan over its lifetimes have resulted in negative «engrams» forming in the mind, causing neuroses and mental problems. They claim that the practice of auditing can remove these engrams; most Scientology groups charge fees for clients undergoing auditing. Once these engrams have been removed, an individual is given the status of «clear». They can take part in a further series of activities that are termed «Operating Thetan» (OT) levels, which require further payments.

The Operating Thetan texts are kept secret from most followers, and are only revealed after adherents have typically given hundreds of thousands of dollars to the organization in order to complete what Scientology refers to as The Bridge to Total Freedom.[12] The Scientology organization has gone to considerable lengths to try to maintain the secrecy of the texts but they are freely available on the internet.[13] These texts say that lives preceding a thetan’s arrival on Earth were lived in extraterrestrial cultures. Scientology doctrine states that any Scientologist undergoing «auditing» will eventually come across and recount what is called the «Incident».[14] The secret texts refer to an alien being called Xenu. They say Xenu was a ruler of a confederation of planets 70 million years ago who brought billions of aliens to Earth and then killed them with thermonuclear weapons. Despite being kept secret from most followers, this forms the central mythological framework of Scientology’s ostensible soteriology.[15] These aspects have become the subject of popular ridicule.

Hubbard wrote primarily science fiction, and had experience with religions such as Thelema. In the late 1940s he created Dianetics, a set of practices which he presented as therapy. Over time, he came to consider auditing useful not just for problems of the mind, but also of the spirit, developing Scientology as an expansion of Dianetics. Although he had framed Dianetics as a «science» — a characterisation rejected by the medical establishment — in the 1950s, for pragmatic legal reasons, he increasingly portrayed Scientology as a religion. In 1954 he established the Church of Scientology in Los Angeles before swiftly establishing similar organisations internationally. Relations with various governments were strained. In the 1970s Hubbard’s followers engaged in a program of criminal infiltration of the U.S. government, resulting in several executives of the organization being convicted and imprisoned for multiple offenses by a U.S. Federal Court. Becoming increasingly reclusive, Hubbard built an elite group called the Sea Organization around himself. After Hubbard’s death in 1986, David Miscavige became head of the Church. From the 1980s, various senior Church members left and established groups such as Ron’s Org, forming the basis of the Free Zone.

From soon after their formation, Hubbard’s groups have generated considerable opposition and controversy, in several instances because of their illegal activities.[16] In January 1951, the New Jersey Board of Medical Examiners brought proceedings against the Dianetic Research Foundation on the charge of teaching medicine without a license.[17] Hubbard himself was convicted in absentia of fraud by a French court in 1978 and sentenced to four years in prison.[18] In 1992, a court in Canada convicted the Scientology organization in Toronto of spying on law enforcement and government agencies, and criminal breach of trust, later upheld by the Ontario Court of Appeal.[19][20] The Church of Scientology was convicted of fraud by a French court in 2009, a judgment upheld by the supreme Court of Cassation in 2013.[21]

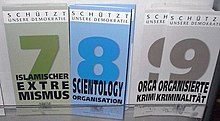

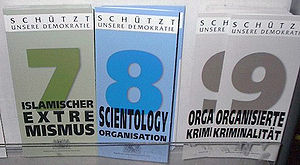

The Church of Scientology has been described by government inquiries, international parliamentary bodies, scholars, law lords, and numerous superior court judgments as both a dangerous cult and a manipulative profit-making business.[28] Following extensive litigation in numerous countries,[29][30] the organization has managed to attain a legal recognition as a religious institution in some jurisdictions, including Australia,[31][32] Italy,[30] and the United States.[33] Germany classifies Scientology groups as an «anti-constitutional sect»,[34][35] while the French government classifies the group as a dangerous cult.[36][37]

Definition and classification

The sociologist Stephen A. Kent views the Church of Scientology as «a multifaceted transnational corporation, only one element of which is religious».[38] The historian of religion Hugh Urban described Scientology as a «huge, complex, and multifaceted movement».[39] Scientology has experienced multiple schisms during its history.[40] While the Church of Scientology was the original promoter of the movement, various independent groups have split off to form independent Scientology groups. Referring to the «different types of Scientology,» the scholar of religion Aled Thomas suggested it was appropriate to talk about «Scientologies.»[41]

Urban described Scientology as representing a «rich syncretistic blend» of sources, including elements from Hinduism and Buddhism, Thelema, new scientific ideas, science-fiction, and from psychology and popular self-help literature available by the mid-20th century.[42] The ceremonies, structure of the prayers, and attire worn by ministers in the Church all reflect the influence of Protestantism.[43]

Hubbard claimed that Scientology was «all-denominational»,[44] and members of the Church are not prohibited from active involvement in other religions.[45] Scholar of religion Donald Westbrook encountered Church members who also practiced Judaism, Christianity, Buddhism, and the Nation of Islam; one was a Baptist minister.[44] In practice, however, Westbrook noted that most Church members consider Scientology to be their only commitment, and the deeper their involvement in the Church became, the less likely they were to continue practicing other traditions.[44]

Debates over classification

Arguments as to whether Scientology should be regarded as a cult, a business, or a religion have gone on for many years.[46] Many Scientologists consider it to be their religion.[47] Its founder, L. Ron Hubbard, presented it as such,[48] but the early history of the Scientology organization, and Hubbard’s policy directives, letters, and instructions to subordinates, indicate that his motivation for doing so was as a legally pragmatic move.[6] In many countries the Church of Scientology has engaged in legal challenges to secure recognition as a tax-exempt religious organization,[49] and it is now legally recognized as such in some jurisdictions, including the United States, but in only a minority of those in which it operates.[50][51]

Many scholars of religion have referred to Scientology as a religion,[52] as has the Oxford English Dictionary.[53] The sociologist Bryan R. Wilson compared Scientology with 20 criteria that he associated with religion and concluded that the movement could be characterised as such.[54] Allan W. Black analysed Scientology through the seven «dimensions of religion» set forward by the scholar Ninian Smart and also decided that Scientology met those criteria for being a religion.[55] The sociologist David V. Barrett noted that there was a «strong body of evidence to suggest that it makes sense to regard Scientology as a religion»,[56] while scholar of religion James R. Lewis commented that «it is obvious that Scientology is a religion.»[57]

More specifically, many scholars have described Scientology as a new religious movement.[58] Various scholars have also considered it within the category of Western esotericism,[59] while the scholar of religion Andreas Grünschloß noted that it was «closely linked» to UFO religions,[60] as science-fiction themes are evident in its theology.[61] Scholars have also varyingly described it as a «psychotherapeutically oriented religion»,[62] a «secularized religion,»[63] a «postmodern religion,»[64] a «privatized religion,»[65] and a «progressive-knowledge» religion.[66] According to scholar of religion Mary Farrell Bednarowski, Scientology describes itself as drawing on science, religion, psychology and philosophy but «had been claimed by none of them and repudiated, for the most part, by all».[67]

Government inquiries, international parliamentary bodies, scholars, law lords, and numerous superior court judgments have described Scientology both as a dangerous cult and as a manipulative profit-making business.[68]. These seriously question the categorisation of Scientology as a religion.[50][69] An article in the magazine TIME, «The Thriving Cult of Greed and Power», described Scientology as «a ruthless global scam».[1] The Church of Scientology’s attempts to sue the publishers for libel and to prevent republication abroad were dismissed.[70] The notion of Scientology as a religion is strongly opposed by the anti-cult movement.[71] The Church has not received recognition as a religious organization in the majority of countries it operates in;[72] its claims to a religious identity have been particularly rejected in continental Europe, where anti-Scientology activists have had a greater impact on public discourse than in Anglophone countries.[51] These critics maintain that the Church is a commercial business that falsely claims to be religious,[73] or alternatively a form of therapy masquerading as religion.[74] Grünschloß commented that those rejecting the categorisation of Scientology as a religion acted under the «misunderstanding» that to call it a religion means that «one has approved of its basic goodness.»[75] He stressed that labelling Scientology a religion does not mean that it is «automatically promoted as harmless, nice, good, and humane.»[76]

Etymology

The word Scientology, as coined by Hubbard, is a derivation from the Latin word scientia («knowledge», «skill»), which comes from the verb scīre («to know»), with the suffix -ology, from the Greek λόγος lógos («word» or «account [of]»).[77][78] Hubbard claimed that the word «Scientology» meant «knowing about knowing or science of knowledge«.[79] The name «Scientology» deliberately makes use of the word «science»,[80] seeking to benefit from the «prestige and perceived legitimacy» of natural science in the public imagination.[81] In doing so Scientology has been compared to religious groups like Christian Science and the Science of Mind which employed similar tactics.[82]

The term «Scientology» had been used in published works at least twice before Hubbard.[79] In The New Word (1901) poet and lawyer Allen Upward first used scientology to mean blind, unthinking acceptance of scientific doctrine (compare scientism).[83] In 1934, philosopher Anastasius Nordenholz published Scientology: Science of the Constitution and Usefulness of Knowledge, which used the term to mean the science of science.[84] It is unknown whether Hubbard was aware of either prior usage of the word.[85][86]

History

Hubbard’s early life

L. Ron Hubbard and Thomas S. Moulton in Portland, Oregon, in 1943

Hubbard was born in 1911 in Tilden, Nebraska, the son of a U.S. naval officer.[87] His family were Methodists.[88] Six months later they moved to Oklahoma, and then to Montana, living on a ranch near Helena.[50] In 1923, Hubbard moved to Washington DC.[89] In 1927, he made a summer trip to Hawaii, China, Japan, the Philippines, and Guam, following this with a longer visit to East Asia in 1928.[90] In 1929 he returned to the U.S. to complete high school.[90] In 1930, he enrolled at George Washington University, where he began writing and publishing stories.[91][92] He left university after two years and in 1933 married his first wife, Margaret «Polly» Grubb.[93]

Becoming a professional writer for pulp magazines,[94] Hubbard was elected president of the New York chapter of the American Fiction Guild in 1935.[95] His first novel, Buckskin Brigades, appeared in 1937.[95] From 1938 through till the 1950s, he was part of a group of writers associated with the pulp magazine Astounding Science-Fiction.[96] Urban related that Hubbard became one of the «key figures» in the «golden age» of pulp fiction.[97] In a later document called Excalibur, he recalled a near death experience while under anaesthetic during a dental operation in 1938.[98][99][100]

In 1940, Hubbard was commissioned as a lieutenant (junior grade) in the U.S. Navy. After the Pearl Harbor attack brought the U.S. into the Second World War, he was called to active duty, sent to the Philippines and then Australia.[101] After the war, he married for a second time and returned to writing.[102] He became involved with rocket scientist Jack Parsons and the latter’s Agape Lodge, a Pasadena group practicing Thelema, the religion founded by occultist Aleister Crowley. Hubbard later broke from the group and eloped with Parsons’ girlfriend Betty.[103][104] The Church of Scientology later claimed that Hubbard’s involvement with the Agape Lodge was at the behest of the U.S. intelligence services,[105] although no evidence has appeared to substantiate this.[106] In 1952, Hubbard would call Crowley a «very good friend,» despite having never met him.[107] Although the Church of Scientology denies any influence from Thelema,[108] Urban identified a «significant amount of Crowley’s influence in the early Scientology beliefs and practices of the 1950s».[109]

Dianetics and the origins of Scientology: 1950-1954

The house at Bay Head in Ocean County, New Jersey where Hubbard finished writing Dianetics in late 1949; the Church of Scientology later declared it an L. Ron Hubbard Landmark Site.[110]

During the late 1940s, Hubbard began developing a therapy system called Dianetics,[111] first producing an unpublished manuscript on the subject in 1948.[112] He subsequently published his ideas as the article «Dianetics: The Evolution of a Science» in Astounding Science Fiction in May 1950.[113][114][115] The magazine’s editor, John W. Campbell, was sympathetic.[116]

Later that year, Hubbard published his ideas as the book, Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health.[117] Published by Hermitage House, the first edition contained an introduction from medical doctor Joseph A. Winter and an appendix by the philosopher Will Durant.[118] Dianetics subsequently spent 28 weeks as a New York Times bestseller.[a][119][120] Urban suggested that Dianetics was «arguably the first major book of do-it-yourself psychotherapy».[121]

Dianetics describes a «counseling» technique known as «auditing» in which an auditor assists a subject in conscious recall of traumatic events in the individual’s past. It was originally intended to be a new psychotherapy.[122][123] The stated intent is to free individuals of the influence of past traumas by systematic exposure and removal of the engrams (painful memories) these events have left behind, a process called clearing.[124]

In April 1950 Hubbard founded the Hubbard Dianetic Research Foundation (HDRF) in Elizabeth, New Jersey.[125] He began offering courses teaching people how to become auditors and lectured on the topic around the country.[126] Hubbard’s ideas generated a new Dianetics movement, which grew swiftly,[127] partly because it was more accessible than psychotherapy and promised more immediate progress.[128] Individuals and small groups practicing Dianetics appeared in various places across the U.S. and United Kingdom.[129]

Hubbard continually sought to refine his Dianetics techniques.[130]

In 1951, he introduced E-Meters into the auditing process.[131] The original «Book One Auditing,» which Hubbard promoted in the late 1940s and early 1950s, did not use an E-Meter, but simply entailed a question and answer session between the auditor and client.[132]

Hubbard labelled Dianetics a «science,» rather than considering it a religion.[133] At that time his expressed views of religion were largely negative.[134] He approached both the American Psychiatric Association and the American Medical Association, but neither took Dianetics seriously.[135] Dr. Winter, hoping to have Dianetics accepted in the medical community, submitted papers outlining the principles and methodology of Dianetic therapy to the Journal of the American Medical Association and the American Journal of Psychiatry in 1949, but these were rejected.[136][137] Much of the medical establishment and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) were sceptical and critical of Dianetics;[138] they regarded his ideas as pseudomedicine and pseudoscience.[48] During the early 1950s, several Dianetics practitioners were arrested, charged with practicing medicine without a license.[138]

Hubbard explicitly distanced Dianetics from hypnotism,[139] claiming that the two were diametrically opposed in purpose.[140] However, he acknowledged having used hypnotism during his early research,[141] and various acquaintances reported observing him engaged in hypnotism, sometimes for entertainment purposes.[140][142] Hubbard also acknowledged certain similarities between his ideas and Freudian psychoanalysis, although maintained that Dianetics provided more adequate solutions to a person’s problems than Sigmund Freud’s ideas.[141] Hubbard’s thought was parallel with the trend of humanist psychology at that time, which also came about in the 1950s.[143]

Hubbard’s house in Phoenix, Arizona

As Dianetics developed, Hubbard began claiming that auditing was revealing evidence that people could recall past lives and thus provided evidence of an inner soul or spirit.[144][145] This shift into metaphysical territory was reflected in Hubbard’s second major book on Dianetics, Science of Survival (1951).[146] Some Dianetics practitioners distanced themselves from these claims, believing that they veered into supernaturalism and away from Dianetics’ purported scientific credentials.[147] Several of Hubbard’s followers, including Campbell and Winter, distanced themselves from Hubbard, citing the latter’s dogmatism and authoritarianism.[148]

By April 1951, Hubbard’s HDRF was facing financial ruin and in 1952 it entered voluntary bankruptcy.[147][149][150][151]: 58 Following the bankruptcy, stewardship of the Dianetics copyrights transferred from Hubbard to Don Purcell, who had provided the HDRF with financial support.[152] Purcell then established his own Dianetics center in Wichita, Kansas.[153] Hubbard distanced himself from Purcell’s group and moved to Phoenix, Arizona, where he formed the Hubbard Association of Scientologists.[154] Westbrook commented that Hubbard’s development of the term «Scientology» was «born in part out of legal necessity,» because Purcell owned the copyrights to Dianetics, but also reflected «Hubbard’s new philosophical and theological practices».[155] In the early texts written that year, Hubbard presented Scientology as a new «science» rather than as a religion.[79] In March 1952 he married his third wife, Mary Sue Whipp, who became an important part of his new Scientology movement.[79]

Establishing the Church of Scientology: 1951-1965

As the 1950s developed, Hubbard saw the advantages of having his Scientology movement legally recognised as a religion.[156] Urban noted that Hubbard’s efforts to redefine Scientology as a religion occurred «gradually, in fits and starts, and largely in response to internal and external events that made such a definition of the movement both expedient and necessary».[157] These influences included challenges to Hubbard’s authority within Dianetics, attacks from external groups like the FDA and American Medical Association, and Hubbard’s growing interest in Asian religions and past life memories.[157]

Several other science-fiction writers, and Hubbard’s son, have reported that they heard Hubbard comment that the way to make money was to start a religion.[156]

Harlan Ellison has told a story of seeing Hubbard at a gathering of the Hydra Club in 1953 or 1954. Hubbard was complaining of not being able to make a living on what he was being paid as a science fiction writer. Ellison says that Lester del Rey told Hubbard that what he needed to do to get rich was start a religion.[158]

L. Ron Hubbard originally intended for Scientology to be considered a science, as stated in his writings. In May 1952, Scientology was organized to put this intended science into practice, and in the same year, Hubbard published a new set of teachings as Scientology, a religious philosophy.[159] Marco Frenschkowski quotes Hubbard in a letter written in 1953, to show that he never denied that his original approach was not a religious one: «Probably the greatest discovery of Scientology and its most forceful contribution to mankind has been the isolation, description and handling of the human spirit, accomplished in July 1951, in Phoenix, Arizona. I established, along scientific rather than religious or humanitarian lines that the thing which is the person, the personality, is separable from the body and the mind at will and without causing bodily death or derangement. (Hubbard 1983: 55).»[160]

Following the prosecution of Hubbard’s foundation for teaching medicine without a license, in April 1953 Hubbard wrote a letter proposing that Scientology should be transformed into a religion.[161] As membership declined and finances grew tighter, Hubbard had reversed the hostility to religion he voiced in Dianetics.[162] His letter discussed the legal and financial benefits of religious status.[162] Hubbard outlined plans for setting up a chain of «Spiritual Guidance Centers» charging customers $500 for twenty-four hours of auditing («That is real money … Charge enough and we’d be swamped.»). Hubbard wrote:[163]

I await your reaction on the religion angle. In my opinion, we couldn’t get worse public opinion than we have had or have less customers with what we’ve got to sell. A religious charter would be necessary in Pennsylvania or NJ to make it stick. But I sure could make it stick.

In December 1953, Hubbard incorporated three organizations – a «Church of American Science», a «Church of Scientology» and a «Church of Spiritual Engineering» – in Camden, New Jersey.[142] On February 18, 1954, with Hubbard’s blessing, some of his followers set up the first local Church of Scientology, the Church of Scientology of California, adopting the «aims, purposes, principles and creed of the Church of American Science, as founded by L. Ron Hubbard».[142]

The Founding Church of Scientology in Washington, D.C.

In 1955, Hubbard established the Founding Church of Scientology in Washington, D.C.[145] The group declared that the Founding Church, as written in the certificate of incorporation for the Founding Church of Scientology in the District of Columbia, was to «act as a parent church for the religious faith known as ‘Scientology’ and to act as a church for the religious worship of the faith».[164]

During this period the organization expanded to Australia, New Zealand, France, the United Kingdom and elsewhere. In 1959, Hubbard purchased Saint Hill Manor in East Grinstead, Sussex, United Kingdom, which became the worldwide headquarters of the Church of Scientology and his personal residence. During Hubbard’s years at Saint Hill, he traveled, providing lectures and training in Australia, South Africa in the United States, and developing materials that would eventually become Scientology’s «core systematic theology and praxis.[165]

With the FDA increasingly suspicious of E-Meters, in an October 1962 policy letter Hubbard stressed that these should be presented as religious, rather than medical devices.[166] In January 1963, FDA agents raided offices of the organization, seizing over a hundred E-meters as illegal medical devices and tons of literature that they accused of making false medical claims.[167] The original suit by the FDA to condemn the literature and E-meters did not succeed,[168] but the court ordered the organization to label every meter with a disclaimer that it is purely religious artifact,[169] to post a $20,000 bond of compliance, and to pay the FDA’s legal expenses.[170]

In the course of developing Scientology, Hubbard presented rapidly changing teachings that some have seen as often self-contradictory.[171][172] According to Lindholm, for the inner cadre of Scientologists in that period, involvement depended not so much on belief in a particular doctrine but on unquestioning faith in Hubbard.[172]

With the Church often under heavy criticism, it adopted strong measures of attack in dealing with its critics.[173] In 1966, the Church established a Guardian’s Office (GO), an intelligence unit devoted to undermining those hostile towards Scientology.[174] The GO launched an extensive program of countering negative publicity, gathering intelligence, and infiltrating hostile organizations.[175] In «Operation Snow White», the GO infiltrated the IRS and several other government departments and stole, photocopied, and then returned tens of thousands of documents pertaining to the Church, politicians, and celebrities.[176]

Hubbard’s later life: 1966-1986

In 1966, Hubbard resigned as executive director of the Church.[177][145][178] From that point on, he focused on developing the advanced levels of training.[179] In 1967, Hubbard established a new elite group, the Sea Organization or «SeaOrg», the membership of which was drawn from the most committed members of the Church.[180] With its members living communally and holding senior positions in the Church,[181] the SeaOrg was initially based on three ocean-going ships, the Diana, the Athena, and the Apollo.[179][145] Reflecting Hubbard’s fascination for the navy, members had naval titles and uniforms.[182] In 1975, the SeaOrg moved its operations from the ships to the new Flag Land Base in Clearwater, Florida.[183]

The eight-pointed Scientology cross, one of the symbols created to give Scientology the trappings of a religion[184][6] Urban suggested it was modelled on the eight-pointed cross used by the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.[185]

In 1972, facing criminal charges in France, Hubbard returned to the United States and began living in an apartment in Queens, New York.[186]

In July 1977, police raids on Church premises in Washington DC and Los Angeles revealed the extent of the GO’s infiltration into government departments and other groups.[187] 11 officials and agents of the Church were indicted; in December 1979 they were sentenced to between 4 and 5 years each and individually fined $10,000.[188] Among those found guilty was Hubbard’s then-wife, Mary Sue Hubbard.[176] Public revelation of the GO’s activities brought widespread condemnation of the Church.[188] The Church responded by closing down the GO and expelling those convicted of illegal activities.[188] A new Office of Special Affairs replaced the GO.[189] A Watchdog Committee was set up in May 1979, and in September it declared that it now controlled all senior management in the Church.[49]

At the start of the 1980s, Hubbard withdrew from public life,[190][191][192] with only a small number of senior Scientologists ever seeing him again.[49] 1980 and 1981 saw significant revamping at the highest levels of the Church hierarchy,[188] with many senior members being demoted or leaving the Church.[49] By 1981, the 21-year old David Miscavige, who had been one of Hubbard’s closest aides in the SeaOrg, rose to prominence.[49] That year, the All Clear Unit (ACU) was established to take on Hubbard’s responsibilities.[49] In 1981, the Church of Scientology International was formally established,[193] as was the profit-making Author Services Incorporated (ASI), which controlled the publishing of Hubbard’s work.[194] In 1982, this was followed by the creation of the Religious Technology Center, which controlled all trademarks and service marks.[195][196] The Church had continued to grow; in 1980 it had centers in 52 countries, and by 1992 that was up to 74.[197]

Some senior members who found themselves side-lined regarded Miscavige’s rise to dominance as a coup,[194] believing that Hubbard no longer had control over the Church.[198] Expressing opposition to the changes was senior member Bill Robertson, former captain of the Sea Org’s flagship, Apollo.[182] At an October 1983 meeting, Robertson claimed that the organization had been infiltrated by government agents and was being corrupted.[199] In 1984 he established a rival Scientology group, Ron’s Org,[200] and coined the term «Free Org» which came to encompass all Scientologists outside the Church.[200] Robertson’s departure was the first major schism within Scientology.[199]

During his seclusion, Hubbard continued writing. His The Way to Happiness was a response to a perceived decline in public morality.[197] He also returned to writing fiction, including the sci-fi epic Battlefield Earth and the 10-volume Mission Earth.[197] In 1980, Church member Gerry Armstrong was given access to Hubbard’s private archive so as to conduct research for an official Hubbard biography. Armstrong contacted the Messengers to raise discrepancies between the evidence he discovered and the Church’s claims regarding Hubbard’s life; he duly left the Church and took Church papers with him, which they regained after taking him to court.[201] Hubbard died at his ranch in Creston, California on January 24, 1986.[202][203]

After Hubbard: 1986-

David Miscavige succeeded Hubbard as the head of the Church of Scientology

Miscavige succeeded Hubbard as head of the Church.[182]

In 1991, Time magazine published a frontpage story attacking the Church. The latter responded by filing a lawsuit and launching a major public relations campaign.[204] In 1993, the Internal Revenue Service dropped all litigation against the Church and recognized it as a religious organization,[205] with the UK’s home office also recognizing it as a religious organization in 1996.[206] The Church then focused its opposition towards the Cult Awareness Network (CAN), a major anti-cult group. The Church was part of a coalition of groups what successfully sued CAN, which then collapsed as a result of bankruptcy in 1996.[207]

In 2008, the online activist collective Anonymous launched Project Chanology with the stated aim of destroying the Church; this entailed denial of service attacks against Church websites and demonstrations outside its premises.[208] In 2009, the St Petersburg Times began a new series of exposes surrounding alleged abuse of Church members, especially at their re-education camp at Gilman Hot Springs in California.[209] As well as prompting episodes of BBC’s Panorama and CNN’s AC360 investigating the allegations,[210] these articles launched a new series of negative press articles and books presenting themselves as exposes of the Church.[211]

In 2009, the Church established relations with the Nation of Islam (NOI). Over coming years, thousands of NOI members received introductory Dianetics training.[212] In 2012, Lewis commented on a recent decline in Church membership.[213] Those leaving for the Freezone included large numbers of high-level, long-term Scientologists,[214] among them Mark Rathbun and Mike Rinder.[215][216]

Beliefs and practices

A civilization without insanity, without criminals and without war; where the world can prosper and honest beings can have rights, and where man is free to rise to greater heights, are the aims of Scientology.

— Hubbard, The Aims of Scientology[217][218][219]

Hubbard lies at the core of Scientology.[220] His writings remain the source of Scientology’s doctrines and practices,[221] with the sociologist of religion David G. Bromley describing the religion as Hubbard’s «personal synthesis of philosophy, physics, and psychology.»[222] Hubbard claimed that he developed his ideas through research and experimentation, rather than through revelation from a supernatural source.[223] He published hundreds of articles and books over the course of his life,[224] writings that Scientologists regard as scripture.[225] The Church encourages people to read his work chronologically, in the order in which it was written.[226] It claims that Hubbard’s work is perfect and no elaboration or alteration is permitted.[227] Hubbard described Scientology as an «applied religious philosophy» because, according to him, it consists of a metaphysical doctrine, a theory of psychology, and teachings in morality.[228]

Hubbard developed thousands of neologisms during his lifetime.[227] The nomenclature used by the movement is termed «Scientologese» by members.[229] Scientologists are expected to learn this specialist terminology, the use of which separates followers from non-Scientologists.[227] The Church refers to its practices as «technology,» a term often shortened to «Tech.»[230] Scientologists stress the «standardness» of this «tech», by which they express belief in its infallibility.[231] The Church’s system of pedagogy is called «Study Tech» and is presented as the best method for learning.[232] Scientology teaches that when reading, it is very important not to go past a word one does not understand. A person should instead consult a dictionary as to the meaning of the word before progressing, something Scientology calls «word clearing».[233]

The scholar of religion Dorthe Refslund Christensen described Scientology as being «a religion of practice» rather than «a religion of belief.»[234] According to Scientology, its beliefs and practices are based on rigorous research, and its doctrines are accorded a significance equivalent to scientific laws.[235] Blind belief is held to be of lesser significance than the practical application of Scientologist methods.[235] Adherents are encouraged to validate the practices through their personal experience.[235] Hubbard put it this way: «For a Scientologist, the final test of any knowledge he has gained is, ‘did the data and the use of it in life actually improve conditions or didn’t it?‘«[235] Many Scientologists avoid using the words «belief» or «faith» to describe how Hubbard’s teachings impacts their lives, preferring to say that they «know» it to be true.[236]

Theology and cosmology

May the author of the Universe enable all men to reach an understanding of their spiritual nature. May awareness and understanding of life expand so that all may come to know the author of the universe. And may others also reach this understanding which brings Total Freedom.

— A prayer used by the Church of Scientology[237]

Scientology refers to the existence of a Supreme Being, but practitioners are not expected to worship it.[238] No intercessions are made to seek this Being’s assistance in daily life.[239]

Hubbard referred to the physical universe as the MEST universe, meaning «Matter, Energy, Space and Time».[240] In Scientology’s teaching, this MEST universe is separate from the theta universe, which consists of life, spirituality, and thought.[241] Scientology teaches that the MEST universe is fabricated through the agreement of all thetans (souls or spirits) that it exists,[241] and is therefore an illusion that is only given reality through the actions of thetans themselves.[242]

The Bridge to Total Freedom

Thomas noted that «the primary focus of Scientology is self-improvement»,[243] while scholar of religion Donald Westbrook called it «a religion of self-knowledge».[244] In pursuing a path of self-discovery and self-improvement, Scientologists are expected to be dedicated and actively practice its teachings.[243] Following Hubbard, Scientologists refer to this process as «the Bridge to Total Freedom» or simply «the Bridge.»[245][246]

As promoted by the Church, Scientology involves progressing through a series of levels, at each of which the practitioner is deemed to gain release from certain problems as well as enhanced abilities.[247] The degree system was probably adopted from earlier European organisation such as Freemasonry and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn.[248] Each of these levels, considered a step on «the Bridge,» has a clear concluding point, termed the «End Phenomenon» or «EP»,[249] and completing it is sometimes celebrated with a ceremony termed a «graduation.»[250] In the Church, the path across the Bridge is «commercialized and monetized,» with charges levied for each degree.[251] Proceeding through the Bridge with the Church can cost hundreds of thousands of US dollars.[252] This monetization of spiritual progression has been a recurring source of criticism of Scientology.[251]

The upper levels are reserved for the most committed and well-trained Scientologists.[253] Many of its teachings are private and not disclosed to outsiders.[253] Although many of Hubbard’s writings and other Scientology documents are protected by the Church and not accessible to either non-members or members below a certain rank, some of them have been leaked by ex-members.[254] In trying to prevent dissemination of its secret teachings, the Church has pointed to the respect often accorded to indigenous religions by those refusing to disseminate their secret traditions, arguing that it should be accorded the same respect.[255]

Body and thetan

A thetan is the person himself, not his body or his name or the physical universe, his mind or anything else. It is that which is aware of being aware; the identity which IS the individual. One does not have a thetan, something one keeps somewhere apart from oneself; he is a thetan.

— The Church of Scientology, 1991 [242]

Hubbard taught that there were three «Parts of Man,» the spirit, mind, and body.[256] The first of these is a person’s «true» inner self, a «theta being» or «thetan.»[257] While the thetan is akin to the idea of the soul or spirit found in other traditions,[258] Hubbard avoided terms like «soul» or «spirit» because of their cultural baggage.[259] Hubbard stated that «the thetan is the person. You are YOU in a body.»[241] According to Hubbard, the thetan uses the mind as a means of controlling the body.[260] Scientology teaches that the thetan usually resides within the human skull but can also leave the body, either remaining in close contact with it or being separated altogether.[261]

According to Scientology, a person’s thetan has existed for trillions of years,[242] having lived countless lifetimes,[262] long before entering a physical body it may now inhabit.[261] In their original form, the thetans were simply energy, separate from the physical universe.[242] Each thetan had its own «Home Universe,» and it was through the collision of these that the physical MEST universe emerged.[242] Once MEST was created, Scientology teaches, the thetans began experimenting with human form, ultimately losing knowledge of their origins and becoming trapped in physical bodies.[242] Scientology also maintains that a series of «universal incidents» have undermined the thetans’ ability to recall their origins.[242]

Hubbard taught that thetans brought the material universe into being largely for their own pleasure.[263] The universe has no independent reality but derives its apparent reality from the fact that thetans agree it exists.[264] Thetans fell from grace when they began to identify with their creation rather than their original state of spiritual purity.[263] Eventually they lost their memory of their true nature, along with the associated spiritual and creative powers. As a result, thetans came to think of themselves as nothing but embodied beings.[264]

Reincarnation

Scientology teaches the existence of reincarnation;[265] Hubbard taught that each individual has experienced «past lives», although generally avoided using the term «reincarnation» itself.[266] The movement claims that once a body dies, the thetan enters another body which is preparing to be born.[242] It rejects the idea that the thetan will be born into a non-human animal on Earth.[267] In Have You Lived Before This Life?, Hubbard recounted accounts of past lives stretching back 55 billion years, often on other planets.[107]

Exteriorization

In Scientology, «exteriorization» refers to the thetan leaving the physical body, if only for a short time, during which it is not encumbered by the physical universe and exists in its original state.[262] Scientology aims to «exteriorize» the thetan from the body, so that the thetan remains close to the body and capable of controlling its actions, but not inside of it, where it can confuse «beingness with mass» and the body.[268] In this way, it seeks to ensure the thetan is unaffected by the trauma of the physical universe while still retaining full control of the mind and body.[261] Some Scientologists claim that they experienced exteriorization while auditing, while Westbrook encountered one high-ranking Church member who reported being exterior most of the time.[262]

The purpose of Scientology is to free the thetan from the confines of the physical MEST universe,[241] thus returning it to its original state.[261] This idea of liberating the spiritual self from the physical universe has drawn comparisons with Buddhism.[241] Although Hubbard’s understanding of Buddhism during the 1950s was limited,[269] Scientological literature has presented its teachings as the continuation and fulfilment of The Buddha’s ideas.[270] In one publication, Hubbard toyed with the idea that he was Maitreya, the future enlightened being prophesied in some forms of Mahayana Buddhism;[271] some Scientologists do regard him as Maitreya.[272] The concept of the thetan has also been observed as being very similar to those promulgated in various mid-20th century UFO religions.[223]

Reactive mind, traumatic memories, and auditing

Prior to establishing Scientology, Hubbard formed a system termed «Dianetics»,[273] and it is from this that Scientology grew.[274] Dianetics presents two major divisions of the mind: the analytical and the reactive mind.[139][275] Dianetics claims that the analytical mind is accurate, rational, and logical, representing what Hubbard called a «flawless computer».[139] The reactive mind is thought to record all pain and emotional trauma.[264][276]

Hubbard claimed that the «reactive» mind stores traumatic experiences in pictorial forms which he termed «engrams.»[277] Dianetics holds that even if the traumatic experience is forgotten, the engram remains embedded in the reactive mind.[273] Hubbard maintained that humans develop engrams from as far back as during incubation in the womb,[273] as well as from their «past lives».[278] Hubbard taught that these engrams cause people problems, ranging from neurosis and physical sickness to insanity.[139][263] The existence of engrams has never been verified through scientific investigation.[279]

Scientology maintains that the mind holds a timeline of a person’s memories, called the «time track.»[280] Each specific memory is a «lock».[281]

Auditing

An auditor and client using an E-Meter

According to Dianetics, engrams can be deleted through a process termed «auditing».[282] Auditing remains the central activity within Scientology,[283] and has been described by scholars of religion as Scientology’s «core ritual»,[284] «primary ritual activity,»[285] and «most sacred process.»[286] The person being audited is called the «Pre-Clear»;[139] the person conducting the procedure is the «auditor».[287] Auditing usually involves a question and answer session between an auditor and their client, the Pre-Clear.[288][289]

An electronic device called the Hubbard Electrometer or electro-psychometer, or more commonly the E-meter, is also typically involved.[290] The client holds two metal canisters, which are connected via a cable to the main box part of the device. This emits a small electrical flow through the client and then back into the box, where it is measured on a needle.[291] It thus detects fluctuations in electrical resistance within the client’s body.[290][289]

The auditor operates two dials on the main part of the device; the larger is the «tone arm» and is used to adjust the voltage, while the smaller «sensitivity knob» influences the amplitude of the needle’s movement.[227] The auditor then interprets the needle’s movements as it responds when the client is asked and answers questions.[227] The movement of the needle is not visible to the client and the auditor writes down their observations rather than relaying them to the client.[227] Hubbard claimed that the E-Meter «measures emotional reaction by tiny electrical impulses generated by thought».[292] Scientologists believe that the auditor locates the points of resistance and converts their form into energy, which can then be discharged.[247] The auditor is believed to be able to detect items that the client may not wish to admit or which is concealed below the latter’s consciousness.[293]

During the auditing process, the auditor is trained to observe the client’s emotional state in accordance with an «emotional tone scale.»[294][151]: 109 The tone scale stretches from tone 0.0, marking «death», to tone 40.0, meaning «Serenity of Beingness.»[295] The client will be located at different points on the tone scale according to their present emotional state.[295] Scientologists maintain that knowing a person’s place on the scale makes it easier to predict his or her actions and assists in bettering his or her condition.[296]

Auditing can be an emotional experience for the client, with some crying during it.[297] Many ex-Scientologists still believe in the efficacy of Dianetics.[273] Urban reported that «even the most cynical ex-Scientologists I’ve talked to recount many positive experiences, insights, and realizations achieved through auditing.»[298]

Scientology doctrine claims that through auditing, people can solve their problems and free themselves of engrams.[299] It also claims that this restores them to their «natural condition» as thetans and enables them to be «at cause» in their daily lives, responding rationally and creatively to life events, rather than reacting to them under the direction of stored engrams.[300]

Once an area of concern has been identified, the auditor asks the individual specific questions about it to help him or her eliminate the difficulty, and uses the E-meter to confirm that the «charge» has been dissipated.[289] As the individual progresses up the «Bridge to Total Freedom», the focus of auditing moves from simple engrams to engrams of increasing complexity and other difficulties.[289] At the more advanced OT levels, Scientologists act as their own auditors («solo auditors»).[289]

Complications and costs

Scientology teaches that auditing can be hindered if the client is under the influence of drugs.[301] Clients are thus advised to undertake the Purification Rundown for two to three weeks to detoxify the body prior to embarking on an auditing course.[302] Also known as the Purification Program or Purif, the Purification Rundown focuses on removing the influence of both medical and recreational drugs from the body through a routine of exercise, saunas, and healthy eating.[303] The Church has Purification Centres where these activities can take place in most of its Orgs,[301] while Free Zone Scientologists have sometimes employed public saunas for the purpose.[304] Other Freezoners have argued that the impact of drugs can be countered through ordinary auditing, with no need for the Purification Rundown.[305]

If a client is deemed to lack the appropriate energy to undergo auditing at a particular time, the auditor may take them on a «locational,» a guided walk in which they are asked to look at objects they pass by.[306] If auditing fails in its goals, Scientologists often believe that this is due to a lack of sincerity on the part of the person being audited.[307] Hubbard insisted that the E-Meter was infallible and that any errors were down to the auditor rather than the device.[308]

Undertaking a full course of auditing with the Church is expensive,[309] although the prices are not often advertised publicly.[310] In a 1964 letter, Hubbard stated that a 25 hour block of auditing should cost the equivalent of «three months’ pay for the average middle class working individual.»[310] In 2007, the fee for a 12 and a half hour block of auditing at the Church’s Tampa Org was $4000.[311] The Church is often criticised for the prices it charges for auditing.[311] Hubbard stated that charging for auditing was necessary because the practice required an exchange, and should the auditor not receive something for their services it could harm both parties.[311]

Going Clear

In Scientology’s teaching, removing all engrams from a person’s mind transforms them from being «Pre-Clear» to a state of «Clear.»[312] Once a person is Clear, Scientology teaches that they are capable of new levels of spiritual awareness.[313] In the 1960s, the Church stated that a «Clear is wholly himself with incredible awareness and power.»[266] It claims that a Clear will have better health, improved hearing and eyesight, and greatly increased intelligence;[314] Hubbard claimed that Clears do not suffer from colds or allergies.[315] Hubbard stated that anyone who becomes Clear will have «complete recall of everything which has ever happened to him or anything he has ever studied».[316]

Individuals who have reached Clear have claimed a range of superhuman abilities, including seeing through walls, remote viewing, and telepathic communication,[107] although the Church discourages them from displaying their advanced powers to anyone but senior Church members.[317]

Hubbard claimed that once a person reaches Clear, they will remain that way permanently.[309] The Church marks the attainment of Clear status by giving an individual their own International Clear Number, which is marked on a silver bracelet, and a certificate. [317] Hubbard first began presenting people that it claimed had reached Clear to the public in the 1950s.[309] In 1979, it claimed that 16,849 people had gone Clear,[318] and in 2018 claimed 69,657 Clears.[319] In 2019, Westbrook suggested that «at least 90%» of Church members had yet to reach the state of Clear,[319] meaning that the «vast majority» remained on the lower half of the Bridge.[320] Scientology’s aim is to «clear the planet», that is, clear all people in the world of their engrams.[321]

Introspection Rundown

The Introspection Rundown is a controversial Church of Scientology auditing process that is intended to handle a psychotic episode or complete mental breakdown. Introspection is defined for the purpose of this rundown as a condition where the person is «looking into one’s own mind, feelings, reactions, etc.»[322] The Introspection Rundown came under public scrutiny after the death of Lisa McPherson in 1995.[323]

The Operating Thetan levels

The church’s cruise ship, the Freewinds, staffed by Sea Org members, with OT symbol on side of ship

The degrees above the level of Clear are called «Operating Thetan» or OT.[324] Hubbard described there as being 15 OT levels, although had only completed eight of these during his lifetime.[325] OT levels nine to 15 have not been reached by any Scientologist;[326] in 1988 the Church stated that OT levels nine and ten would only be released when certain benchmarks in the Church’s expansion had been achieved.[327]

To gain the OT levels of training, a Church member must go to one of the Advanced Organisations or Orgs, which are based in Los Angeles, Clearwater, East Grinstead, Copenhagen, Sydney, and Johannesburg.[328] OT levels six and seven are only available at Clearwater.[329] The highest level, OT eight, is disclosed only at sea on the Scientology ship Freewinds, operated by the Flag Ship Service Org.[330][331] Scholar of religion Aled Thomas suggested that the status of a person’s level creates an internal class system within the Church.[332]

The Church claims that the material taught in the OT levels can only be comprehended once its previous material has been mastered and is therefore kept confidential until a person reaches the requisite level.[333] Higher-level Church members typically refuse to talk about the contents of these OT levels.[334] Those progressing through the OT levels are taught additional, more advanced auditing techniques;[259] one of the techniques taught is a method of auditing oneself,[335] which is the necessary procedure for reaching OT level seven.[329]

Space opera and the Wall of Fire

Reflecting a strong science-fiction theme within its theology,[61] Scientology’s teachings make reference to «space opera,» a term denoting events in the distant past in which «spaceships, spacemen, [and] intergalactic travel» all feature.[336] This incorporates what the scholar of religion Mikael Rothstein referred to the «Xenu myth», a story concerning humanity’s origins on Earth. This myth was something that Rothstein described as being «the basic (sometimes implicit) mythology of the movement».[337]

Hubbard wrote about a great catastrophe that took place 75 million years ago.[66] He referred to this as «Incident 2,» one of several «Universal Incidents» that hinder the thetan’s ability to remember its origins.[242] According to this story, 75 million years ago there was a Galactic Federation of 76 planets ruled over by a leader called Xenu. The Federation was overpopulated and to deal with this problem Xenu transported large numbers of people to the planet Teegeeack (Earth). He then detonated hydrogen bombs inside volcanoes to exterminate this surplus population.[338] The thetans of those killed were then «packaged,» by which Hubbard meant that they were clustered together. Implants were inserted into them, designed to kill any body that these thetans would subsequently inhabit should they recall the event of their destruction.[339] After the Teegeeack massacre, several of the officers in Xenu’s service rebelled against him, ultimately capturing and imprisoning him.[340]

According to OT documents discussing Incident 2, the bodies of those Xenu placed on Teegeeack were destroyed but their inner thetans survived and continue to carry the trauma of this event.[242] Scientology maintains that some of these traumatised thetans which lack bodies of their own become «body thetans,» clustering around living people and negatively impacting them.[341] Many of the advanced auditing techniques taught to Scientologists focus on dealing with these body thetans, awakening them from the amnesia they experience and allowing them to detach from the bodies they cluster around. Once free they are capable of either being born into bodies of their choosing or remaining detached from any physical form.[342]

Hubbard claimed to have discovered the Xenu myth in December 1967, having taken the «plunge» deep into his «time track.»[343] He commented that he was «probably the only one ever to do so in 75,000,000 years.»[339] Scientology teaches that attempting to recover this information from the «time track» typically results in an individual’s death, caused by the presence of Xenu’s implants, but that because of Hubbard’s «technology» this death can be avoided.[344]

A man dressed as Xenu carrying an E-meter; Scientology’s critics often use Xenu to mock the movement[345]

As the Church argues that learning the Xenu myth can be harmful for those unprepared for it,[346] the documents discussing Xenu were restricted for those Church members who had reached the OT III level, known as the «Wall of Fire.»[347] These OT III teachings about Xenu were later leaked by ex-members,[348] becoming a matter of public record after being submitted as evidence in court cases.[349][350] They are now widely available online.[351] The Church claims that the leaked documents have been distorted,[352] and that the OT level texts are only religiously meaningful in the context of the OT courses in which they are provided, thus being incomprehensible to outsiders.[353] Church members who have reached the OT III level routinely deny these teachings exist.[354] Hubbard however talked about Xenu on several occasions,[355] the Xenu story bears similarities with some of the science-fiction stories Hubbard published,[356] and Rothstein noted that «substantial themes from the Xenu story are detectable» in Hubbard’s book Scientology – A History of Man.[357]

Critics of Scientology regularly employ reference to Xenu to mock the movement,[345] believing that the story will be regarded as absurd by outsiders and thus prove detrimental to Scientology.[358] Critics have also highlighted factual discrepancies regarding the myth; geologists demonstrate that the Mauna Loa volcano, which appears in the myth, is far younger than 75 million years old.[355] Scientologists nevertheless regard it as a factual account of past events.[359]

Ethics, morality, and gender roles

Scientology sets forth explicit ethical guidelines for its followers to adhere to.[360] In the Scientology worldview, humans are regarded as being essentially good.[361] Its value system was largely compatible with the Protestant-dominant culture in which it arose.[43]

Scientology professes belief in fundamental human rights.[362] The liberal or personal rights of the individual are often stressed as being at the core of the Scientologist’s creed,[363] and Scientologists have lead campaigns to promote the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[364]

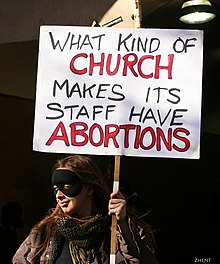

Gender and sexuality have been controversial issues in Scientology’s history.[365] Women are able to become ministers and rise through the Church ranks in the same manner as men.[366] Hubbard’s writing makes androcentric assumptions through its use of language,[367] with critics of Scientology accusing him of being a misogynist.[368] Hubbard’s use of language was also heteronormative,[367] and he described same-sex attraction as a perversion and physical illness, rendering homosexuals «extremely dangerous to society.»[369] Various Freezone Scientologists have alleged that they encountered homophobia within the Church.[370] The Church’s stance on same-sex sexuality has drawn criticism from gay rights activists.[371]

Survival and the Eight Dynamics

Scientology emphasizes the importance of «survival», which it subdivides into eight classifications that are referred to as «dynamics».[372][373] The first dynamic is individual; the second pertains to procreation and the family; the third to a group or groups a person belongs to; the fourth is humanity; the fifth is the environment; the sixth is the physical universe; the seventh is the spiritual universe; and the eighth is infinity or divinity.[374][373] According to Hubbard’s teaching, the optimum solution to any problem is believed to be the one that brings the greatest benefit to the greatest number of dynamics.[244][373] Westbrook stated that this «utilitarian principle is central to an understanding of Scientology ethics for church members.»[244]

ARC and KRC triangles

The Scientology symbol is composed of the letter S, which stands for Scientology, and the ARC and KRC triangles, two important concepts in Scientology.

The ARC and KRC triangles are concept maps which show a relationship between three concepts to form another concept. These two triangles are present in the Scientology symbol. The lower triangle, the ARC triangle, is a summary representation of the knowledge the Scientologist strives for.[263] It encompasses Affinity (affection, love or liking), Reality (consensual reality) and Communication (the exchange of ideas).[263] Scientology teaches that improving one of the three aspects of the triangle «increases the level» of the other two, but Communication is held to be the most important.[246] The upper triangle is the KRC triangle, the letters KRC positing a similar relationship between Knowledge, Responsibility and Control.[375]

Among Scientologists, the letters ARC are used as an affectionate greeting in personal communication, for example at the end of a letter.[376] Social problems are ascribed to breakdowns in ARC – in other words, a lack of agreement on reality, a failure to communicate effectively, or a failure to develop affinity.[377] These can take the form of overts – harmful acts against another, either intentionally or by omission – which are usually followed by withholds – efforts to conceal the wrongdoing, which further increase the level of tension in the relationship.[377]

Views of Hubbard

Scientologists view Hubbard as an extraordinary man, but do not worship him as a deity.[378] They regard him as the preeminent Operating Thetan who remained on Earth in order to show others the way to spiritual liberation,[227] the man who discovered the source of human misery and a technology allowing everyone to recognise their true potential.[379] Church of Scientology management frames Hubbard’s physical death as «dropping his body» to pursue higher levels of research not possible with an Earth-bound body.[380]

Scientologists often refer to Hubbard affectionately as «Ron,»[381] and many refer to him as their «friend.»[382] The Church operates a calendar in which 1950, the year in which Hubbard’s book Dianetics was published, is considered year zero, the beginning of an era. Years after that date are referred to as «AD» for «After Dianetics.»[383] They have also buried copies of his writings preserved on stainless steel disks in a secure underground vault in the hope of preserving them from major catastrophe. [379] The Church’s view of Hubbard is presented in their authorised biography of him, their RON series of magazines, and their L. Ron Hubbard Life Exhibition in Los Angeles.[380] The Church’s accounts of Hubbard’s life have been characterised as being largely hagiographical,[384] seeking to present him as «a person of exceptional character, morals and intelligence».[385] Critics of Hubbard and his Church claim that many of the details of his life as he presented it were false.[386]

Every Church Org maintains an office set aside for Hubbard in perpetuity, set out to imitate those he used in life,[387] and will typically also have busts of him on display.[388] In 2005 the Church set out certain locations associated with his life as «L. Ron Hubbard Landmark Sites» that Scientologists can visit; these are in the US, UK, and South Africa.[389] Westbrook considered these to be pilgrimage sites for adherents.[390]

Many Scientologists travel to Saint Hill Manor as a form of pilgrimage.[391]

Scientology ceremonies

Ceremonies overseen by the Church fall into two main categories; Sunday services and ceremonies marking particular events in a person’s life.[392] The latter include weddings, child naming ceremonies, and funerals.[263] Friday services are held to commemorate the completion of a person’s services during the prior week.[263] Ordained Scientology ministers may perform such rites.[263] However, these services and the clergy who perform them play only a minor role in Scientologists’ lives.[393]

The Church’s Sunday services begin with the minister giving a short welcoming speech, after which they read aloud the principles of Scientology and oversee a silent prayer. They then read a text by Hubbard and either give their own sermon or play a recording of Hubbard lecturing. The congregation may then ask the minister questions about what they have just heard. Next, prayers are offered, for justice, religious freedom, spiritual advancement, and for gaining understanding of the Supreme Being. Announcements will then be read out and finally the service will end with a hymn or the playing of music.[394] Some Church members regularly attend these services, whereas others go rarely or never.[239] Services can be poorly attended,[395] although are open for anyone to attend, including non-Scientologists.[253]

There are two main celebrations each year.[396] The first, «the Birthday Event,» celebrates Hubbard’s birthday each March 13.[397] The second, «the May 9th Event,» marks the date on which Dianetics was first published.[398] The main celebrations of these events take place at the Church’s Clearwater headquarters, which are filmed and then distributed to other Church centers across the world. On the following weekend, this footage is screened at these centers, so Church members elsewhere can gather to watch it.[399]

Weddings, naming ceremonies, and funerals

At Church wedding services, the two partners are requested to remain faithful and assist each other.[237] These weddings employ Scientological terminology, for instance with the minister asking those being married if they have «communicated» their love to each other and mutually «acknowledged» this.[400] The Church’s naming ceremony for infants is designed to help orient a thetan in its new body and introduce it to its godparents.[401] During the ceremony, the minister reminds the child’s parents and godparents of their duty to assist the newly reborn thetan and to encourage it towards spiritual freedom.[401]

Church funerals may take place in the home or the chapel. If in the latter, there is a procession to the altar, before which the coffin is placed atop a catafalque.[401] The minister reminds those assembled about reincarnation and urges the thetan of the deceased to move on and take a new body.[401] The formal ordination of ministers features the new minister reading aloud the auditor’s code and the code of Scientologists and promising to follow them.[402] The new minister is then presented with the eight-pronged cross of the Church on a chain.[402]

Rejection of psychology and psychiatry

Scientologists on an anti-psychiatry demonstration

Scientology is vehemently opposed to psychiatry and psychology.[403][404][405] Psychiatry rejected Hubbard’s theories in the early 1950s and in 1951, Hubbard’s wife Sara consulted doctors who recommended he «be committed to a private sanatorium for psychiatric observation and treatment of a mental ailment known as paranoid schizophrenia».[406][407]

Hubbard taught that psychiatrists were responsible for a great many wrongs in the world, saying that psychiatry has at various times offered itself as a tool of political suppression and «that psychiatry spawned the ideology which fired Hitler’s mania, turned the Nazis into mass murderers, and created the Holocaust».[406] Hubbard created the anti-psychiatry organization Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR), which operates Psychiatry: An Industry of Death, an anti-psychiatry museum.[406]

From 1969, CCHR has campaigned in opposition to psychiatric treatments, electroconvulsive shock therapy, lobotomy, and drugs such as Ritalin and Prozac.[408] According to the official Church of Scientology website, «the effects of medical and psychiatric drugs, whether painkillers, tranquilizers or ‘antidepressants’, are as disastrous» as illegal drugs.[409] Internal Church documents reveal the intent of eradicating psychiatry and replacing them with therapies from Scientology.[403]

Organization

The Church of Scientology

The Church is headquartered at the Flag Land Base in Clearwater, Florida.[410] This base covers two million square feet and comprises about 50 buildings.[411] The Church operates on a hierarchical and top-down basis,[412] being largely bureaucratic in structure.[413] It claims to be the only true voice of Scientology.[414]

The internal structure of Scientology organizations is strongly bureaucratic with a focus on statistics-based management.[415] Organizational operating budgets are performance-related and subject to frequent reviews.[415]

By 2011, the Church was claiming over 700 centres in 65 countries.[416] Smaller centres are called «missions.»[417] The largest number of these are in the U.S., with the second largest number being in Europe.[418] Missions are established by missionaries, who in Church terminology are called «mission holders.»[419] Church members can establish a mission wherever they wish, but must fund it themselves; the missions are not financially supported by the central Church organization.[420] Mission holders must purchase all of the necessary material from the Church; as of 2001, the Mission Starter Pack cost $35,000.[421]

Each mission or Org is a corporate entity, established as a licensed franchise, and operating as a commercial company.[422] Each franchise sends part of its earnings, which have been generated through beginner-level auditing, to the International Management.[423] Bromley observed that an entrepreneurial incentive system pervades the Church, with individual members and organisations receiving payment for bringing in new people or for signing them up for more advanced services.[424] The individual and collective performances of different members and missions are gathered, being called «stats.»[425] Performances that are an improvement on the previous week are termed «up stats;» those that show a decline are «down stats.»[426]

According to leaked tax documents, the Church of Scientology International and Church of Spiritual Technology in the US had a combined $1.7 billion in assets in 2012, in addition to annual revenues estimated at $200 million a year.[427]

Internal organization

The Church of Spiritual Technology (CST) ranch in Creston, California, where Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard spent his last days. The CST symbol is visible within a racetrack.

The Sea Org is the Church’s primary management unit,[424] containing the highest ranks in the Church hierarchy.[415] Westbrook called its members «the church’s clergy».[249] Its members are often recruited from the children of existing Scientologists,[428] and sign up to a «billion-year contract» to serve the Church.[429] Kent described that for adult Sea Org members with minor children, their work obligations took priority, damaged parent-child relations, and has led to cases of severe child neglect and endangerment.[430]

The Church of Scientology International (CSI) co-ordinates all other branches.[418] In 1982, it founded the Religious Technology Centre to oversee the application of its methods.[431] Missionary activity is overseen by the Scientology Missions International, established in 1981.[419]

The Rehabilitation Project Force (RPF) is the Church’s disciplinary program,[253] one which deals with SeaOrg members deemed to have seriously deviated from its teachings.[432][433] When Sea Org members are found guilty of a violation, they are assigned to the RPF;[433] they will often face a hearing, the «Committee of Evidence,» which determines if they will be sent to the RPF.[434] The RPF operates out of several locations.[435] The RPF involves a daily regimen of five hours of auditing or studying, eight hours of work, often physical labor, such as building renovation, and at least seven hours of sleep.[433] Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley state that scholars and observers have come to radically different conclusions about the RPF and whether it is «voluntary or coercive, therapeutic or punitive».[433] Critics have condemned RPF practices for violating human rights;[253] and criticized the Church for placing children as young as twelve into the RPF, engaging them in forced labor and denying access to their parents, violating Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.[436] The RPF has contributed to characterisations of the Church as a cult.[437]

The Office of Special Affairs or OSA (formerly the Guardian’s Office) is a department of the Church of Scientology which has been characterized as a non-state intelligence agency.[438][439][440] It has targeted critics of the organization for «dead agent» operations, which is mounting character assassination operations against perceived enemies.[441]

A 1990 article in the Los Angeles Times reported that in the 1980s the Scientology organization more commonly used private investigators, including former and current Los Angeles police officers, to give themselves a layer of protection in case embarrassing tactics were used and became public.[442]

The Church of Spiritual Technology (CST) has been described as the «most secret organization in all of Scientology».[443]

Shelly Miscavige, wife of leader David Miscavige, who hasn’t been seen in public since 2007, is said to be held at a CST compound in Twin Peaks, California.[444][445]

Scientology operates hundreds of Churches and Missions around the world.[446] This is where Scientologists receive introductory training, and it is at this local level that most Scientologists participate.[446] Churches and Missions are licensed franchises; they may offer services for a fee provided they contribute a proportion of their income and comply with the Religious Technology Center (RTC) and its standards.[446][447]

The International Association of Scientologists operates to advance the cause of the Church and its members across the world.[448]

Promotional material

The Church of Scientology’s Celebrity Center in Hollywood, Los Angeles

The Church employs a range of media to promote itself and attract converts.[449] Hubbard promoted Scientology through a vast range of books, articles, and lectures.[227] The Church publishes several magazines, including Source, Advance, The Auditor, and Freedom.[224] It has established a publishing press, New Era,[450] and the audiovisual publisher Golden Era.[451] The Church has also used the Internet for promotional purposes.[452] The Church has employed advertising to attract potential converts, including in high-profile locations such as television ads during the 2014 and 2020 Super Bowls.[453]

The Church has long used celebrities as a means of promoting itself, starting with Hubbard’s «Project Celebrity» in 1955 and followed by its first Scientology Celebrity Centre in 1969.[454] The Celebrity Centre headquarters is in Hollywood; other branches are in Dallas, Nashville, Las Vegas, New York City, and Paris.[455] They are described as places where famous people can work on their spiritual development without disruption from fans or the press.[456]

In 1955, Hubbard created a list of 63 celebrities targeted for conversion to Scientology.[457] Prominent celebrities who have joined the Church include John Travolta, Tom Cruise, Kirstie Alley, Nancy Cartwright, and Juliette Lewis.[458] The Church uses celebrity involvement to make itself appear more desirable.[459] Other new religious movements have similarly pursued celebrity involvement such as the Church of Satan, Transcendental Meditation, ISKCON, and the Kabbalah Centre.[460]

The applicability of Hubbard’s teachings also led to the formation of secular organizations focused on fields such as drug abuse awareness and rehabilitation, literacy, and human rights.[461] Several Scientology organizations promote the use of Scientology practices as a means to solve social problems. Scientology began to focus on these issues in the early 1970s, led by Hubbard. The Church of Scientology developed outreach programs to fight drug addiction, illiteracy, learning disabilities and criminal behavior. These have been presented to schools, businesses and communities as secular techniques based on Hubbard’s writings.[462]

The Church places emphasis on impacting society through a range of social outreach programs.[463] To that end it has established a network of organizations involved in humanitarian efforts,[55] most of which operate on a not-for-profit basis.[222] These endeavor’s reflect Scientology’s lack of confidence in the state’s ability to build a just society.[464] Launched in 1966, Narconon is the Church’s drug rehabilitation program, which employs Hubbard’s theories about drugs and treats addicts through auditing, exercise, saunas, vitamin supplements, and healthy eating.[465] Criminon is the Church’s criminal rehabilitation programme.[222][446] Its Applied Scholastics program, established in 1972, employs Hubbard’s pedagogical methods to help students.[466][467] The Way to Happiness Foundation promotes a moral code written by Hubbard, to date translated into more than 40 languages.[467] Narconon, Criminon, Applied Scholastics, and The Way to Happiness operate under the management banner of Association for Better Living and Education.[468][469]

The World Institute of Scientology Enterprises (WISE) applies Scientology practices to business management.[38][467] The most prominent training supplier to make use of Hubbard’s technology is Sterling Management Systems.[467]

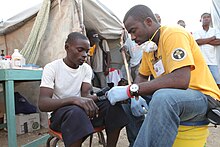

A Church Volunteer Minister, wearing distinct yellow clothing, in Haiti in 2010

Hubbard devised the Volunteer Minister Program in 1973.[470] Wearing distinctive yellow shirts, the Church’s Volunteer Ministers offer help and counselling to those in distress; this includes the Scientological technique of providing «assists».[470] After the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack in New York City, Volunteer Ministers were on the site of Ground Zero within hours of the attack, assisting the rescue workers;[471] they subsequently went to New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina.[39] Accounts of the Volunteer Ministers’ effectiveness have been mixed, and touch assists are not supported by scientific evidence.[472][473][474] The Church’s critics regard this outreach as merely a public relations exercise.[463]

The Church employs its Citizens Commission on Human Rights to combat psychiatry,[423] while Scientologists Taking Action Against Discrimination (STAND) does public relations for Scientology and Scientologists.[475]