|

Thessaloniki Θεσσαλονίκη Saloniki |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

|

Clockwise from top: Aristotle Square, Church of Saint Demetrius, Thessaloniki Concert Hall, Panoramic view of Thessaloniki’s waterfront and the Thermaic Gulf, White Tower of Thessaloniki |

|

|

Flag Seal Logo |

|

| Nickname:

The Nymph of the Thermaic Gulf[1][2] |

|

|

Thessaloniki Thessaloniki Thessaloniki |

|

| Coordinates: 40°38′25″N 22°56′05″E / 40.64028°N 22.93472°ECoordinates: 40°38′25″N 22°56′05″E / 40.64028°N 22.93472°E | |

| Country | Greece |

| Geographic region | |

| Administrative region | Central Macedonia |

| Regional unit | Thessaloniki |

| Founded | 315 BC (2338 years ago) |

| Incorporated | Oct. 1912 (110 years ago) |

| Municipalities | 7 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council government |

| • Mayor | Konstantinos Zervas (New Democracy) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 19.307 km2 (7.454 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 111.703 km2 (43.129 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,285.61 km2 (496.38 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 250 m (820 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population

(2021)[4] |

|

| • Municipality | 317,778 |

| • Rank | 2nd urban, 2nd metro in Greece |

| • Urban | 824,676[3] |

| • Metro | 1,091,424[3] |

| Demonym(s) | Thessalonian, Thessalonican |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal codes |

53xxx, 54xxx, 55xxx, 56xxx |

| Telephone | 2310 |

| Vehicle registration | NAx-xxxx to NXx-xxxx |

| Patron saint | Saint Demetrius (26 October) |

| Gross regional domestic product (PPP 2015) | €18.77 billion ($20.83 billion)[5] |

| • Per capita | €16,900[5] |

| Website | www.thessaloniki.gr |

Thessaloniki (; Greek: Θεσσαλονίκη, [θesaloˈnici] (listen)), also known as Thessalonica (), Saloniki, or Salonica (), is the second-largest city in Greece, with over one million inhabitants in its metropolitan area, and the capital of the geographic region of Macedonia, the administrative region of Central Macedonia and the Decentralized Administration of Macedonia and Thrace.[6][7] It is also known in Greek as η Συμπρωτεύουσα (i Symprotévousa), literally «the co-capital»,[8] a reference to its historical status as the Συμβασιλεύουσα (Symvasilévousa) or «co-reigning» city of the Byzantine Empire alongside Constantinople.[9]

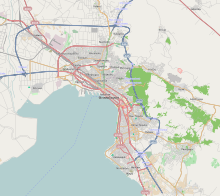

Thessaloniki is located on the Thermaic Gulf, at the northwest corner of the Aegean Sea. It is bounded on the west by the delta of the Axios. The municipality of Thessaloniki, the historical centre, had a population of 317,778 in 2021,[4] while the Thessaloniki metropolitan area had 1,091,424 inhabitants in 2021.[10][3] It is Greece’s second major economic, industrial, commercial and political centre, and a major transportation hub for Greece and southeastern Europe, notably through the Port of Thessaloniki.[11] The city is renowned for its festivals, events and vibrant cultural life in general,[12] and is considered to be Greece’s cultural capital.[12] Events such as the Thessaloniki International Fair and the Thessaloniki International Film Festival are held annually, while the city also hosts the largest bi-annual meeting of the Greek diaspora.[13] Thessaloniki was the 2014 European Youth Capital.[14]

The city was founded in 315 BC by Cassander of Macedon, who named it after his wife Thessalonike, daughter of Philip II of Macedon and sister of Alexander the Great. An important metropolis by the Roman period, Thessaloniki was the second largest and wealthiest city of the Byzantine Empire. It was conquered by the Ottomans in 1430 and remained an important seaport and multi-ethnic metropolis during the nearly five centuries of Turkish rule. It passed from the Ottoman Empire to the Kingdom of Greece on 8 November 1912. Thessaloniki exhibits Byzantine architecture, including numerous Paleochristian and Byzantine monuments, a World Heritage Site, as well as several Roman, Ottoman and Sephardic Jewish structures. The city’s main university, Aristotle University, is the largest in Greece and the Balkans.[15]

Thessaloniki is a popular tourist destination in Greece. In 2013, National Geographic Magazine included Thessaloniki in its top tourist destinations worldwide,[16] while in 2014 Financial Times FDI magazine (Foreign Direct Investments) declared Thessaloniki as the best mid-sized European city of the future for human capital and lifestyle.[17][18]

Names and etymology[edit]

The original name of the city was Θεσσαλονίκη Thessaloníkē. It was named after the princess Thessalonike of Macedon, the half sister of Alexander the Great, whose name means «Thessalian victory», from Θεσσαλός Thessalos, and Νίκη ‘victory’ (Nike), honoring the Macedonian victory at the Battle of Crocus Field (353/352 BC).

Minor variants are also found, including Θετταλονίκη Thettaloníkē,[19][20] Θεσσαλονίκεια Thessaloníkeia,[21] Θεσσαλονείκη Thessaloníkē, and Θεσσαλονικέων Thessalonikéon.[22][23]

The name Σαλονίκη Saloníki is first attested in Greek in the Chronicle of the Morea (14th century), and is common in folk songs, but it must have originated earlier, as al-Idrisi called it Salunik already in the 12th century. It is the basis for the city’s name in other languages: Солѹнъ (Solunŭ) in Old Church Slavonic, סאלוניקו[24][25] (Saloniko) in Judeo-Spanish (שאלוניקי prior to the 19th century[25]) סלוניקי (Saloniki) in Hebrew, (Selenik) in Albanian language, سلانیك (Selânik) in Ottoman Turkish and Selânik in modern Turkish, Salonicco in Italian, Solun or Солун in the local and neighboring South Slavic languages, Салоники (Saloníki) in Russian, Sãrunã in Aromanian[26] and Săruna in Megleno-Romanian.[27]

In English, the city can be called Thessaloniki, Salonika, Thessalonica, Salonica, Thessalonika, Saloniki, Thessalonike, or Thessalonice. In printed texts, the most common name and spelling until the early 20th century was Thessalonica; through most of rest of the 20th century, it was Salonika. By about 1985, the most common single name became Thessaloniki.[28][29] The forms with the Latin ending -a taken together remain more common than those with the phonetic Greek ending -i and much more common than the ancient transliteration -e.[30]

Thessaloniki was revived as the city’s official name in 1912, when it joined the Kingdom of Greece during the Balkan Wars.[31] In local speech, the city’s name is typically pronounced with a dark and deep L, characteristic of the accent of the modern Macedonian dialect of Greek.[32][33] The name is often abbreviated as Θεσ/νίκη.[34]

History[edit]

From classical antiquity to the Roman Empire[edit]

Ancient coin depicting Cassander, son of Antipater, and founder of the city of Thessaloniki

The city was founded around 315 BC by the King Cassander of Macedon, on or near the site of the ancient town of Therma and 26 other local villages.[35][36] He named it after his wife Thessalonike,[37] a half-sister of Alexander the Great and princess of Macedonia as daughter of Philip II. Under the kingdom of Macedonia the city retained its own autonomy and parliament[38] and evolved to become the most important city in Macedonia.[37]

Twenty years after the fall of the Kingdom of Macedonia in 168 BC, in 148 BC, Thessalonica was made the capital of the Roman province of Macedonia.[39] Thessalonica became a free city of the Roman Republic under Mark Antony in 41 BC.[37][40] It grew to be an important trade hub located on the Via Egnatia,[41] the road connecting Dyrrhachium with Byzantium,[42] which facilitated trade between Thessaloniki and great centres of commerce such as Rome and Byzantium.[43] Thessaloniki also lies at the southern end of the main north–south route through the Balkans along the valleys of the Morava and Axios river valleys, thereby linking the Balkans with the rest of Greece.[44] The city became the capital of one of the four Roman districts of Macedonia;.[41]

At the time of the Roman Empire, about 50 AD, Thessaloniki was also one of the early centres of Christianity; while on his second missionary journey, Paul the Apostle visited this city’s chief synagogue on three Sabbaths and sowed the seeds for Thessaloniki’s first Christian church. Later, Paul wrote letters to the new church at Thessaloniki, with two letters to the church under his name appearing in the Biblical canon as First and Second Thessalonians. Some scholars hold that the First Epistle to the Thessalonians is the first written book of the New Testament.[45]

In 306 AD, Thessaloniki acquired a patron saint, St. Demetrius, a Christian whom Galerius is said to have put to death. Most scholars agree with Hippolyte Delehaye’s theory that Demetrius was not a Thessaloniki native, but his veneration was transferred to Thessaloniki when it replaced Sirmium as the main military base in the Balkans.[46] A basilical church dedicated to St. Demetrius, Hagios Demetrios, was first built in the fifth century AD and is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

When the Roman Empire was divided into the tetrarchy, Thessaloniki became the administrative capital of one of the four portions of the Empire under Galerius Maximianus Caesar,[47][48] where Galerius commissioned an imperial palace, a new hippodrome, a triumphal arch and a mausoleum, among other structures.[48][49][50]

In 379, when the Roman Prefecture of Illyricum was divided between the East and West Roman Empires, Thessaloniki became the capital of the new Prefecture of Illyricum.[41] The following year, the Edict of Thessalonica made Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire.[51] In 390, Gothic troops under the Roman Emperor Theodosius I, led a massacre against the inhabitants of Thessalonica, who had risen in revolt against the Gothic soldiers. By the time of the Fall of Rome in 476, Thessaloniki was the second-largest city of the Eastern Roman Empire.[43]

Byzantine era and Middle Ages[edit]

From the first years of the Byzantine Empire, Thessaloniki was considered the second city in the Empire after Constantinople,[52][53][54] both in terms of wealth and size,[52] with a population of 150,000 in the mid-12th century.[55] The city held this status until its transfer to Venetian control in 1423. In the 14th century, the city’s population exceeded 100,000 to 150,000,[56][57][58] making it larger than London at the time.[59]

During the sixth and seventh centuries, the area around Thessaloniki was invaded by Avars and Slavs, who unsuccessfully laid siege to the city several times, as narrated in the Miracles of Saint Demetrius.[60] Traditional historiography stipulates that many Slavs settled in the hinterland of Thessaloniki;[61] however, modern scholars consider this migration to have been on a much smaller scale than previously thought.[61][62] In the ninth century, the Byzantine missionaries Cyril and Methodius, both natives of the city, created the first literary language of the Slavs, the Old Church Slavonic, most likely based on the Slavic dialect used in the hinterland of their hometown.[63][64][65][66][67]

A naval attack led by Byzantine converts to Islam (including Leo of Tripoli) in 904 resulted in the sack of the city.[68][69]

The economic expansion of the city continued through the 12th century as the rule of the Komnenoi emperors expanded Byzantine control to the north. Thessaloniki passed out of Byzantine hands in 1204,[70] when Constantinople was captured by the forces of the Fourth Crusade and incorporated the city and its surrounding territories in the Kingdom of Thessalonica[71] — which then became the largest vassal of the Latin Empire. In 1224, the Kingdom of Thessalonica was overrun by the Despotate of Epirus, a remnant of the former Byzantine Empire, under Theodore Komnenos Doukas who crowned himself Emperor,[72] and the city became the capital of the short-lived Empire of Thessalonica.[72][73][74][75] Following his defeat at Klokotnitsa however in 1230,[72][76] the Empire of Thessalonica became a vassal state of the Second Bulgarian Empire until it was recovered again in 1246, this time by the Nicaean Empire.[72]

In 1342,[77] the city saw the rise of the Commune of the Zealots, an anti-aristocratic party formed of sailors and the poor,[78] which is nowadays described as social-revolutionary.[77] The city was practically independent of the rest of the Empire,[77][78][79] as it had its own government, a form of republic.[77] The zealot movement was overthrown in 1350 and the city was reunited with the rest of the Empire.[77]

The capture of Gallipoli by the Ottomans in 1354 kicked off a rapid Turkish expansion in the southern Balkans, conducted both by the Ottomans themselves and by semi-independent Turkish ghazi warrior-bands. By 1369, the Ottomans were able to conquer Adrianople (modern Edirne), which became their new capital until 1453.[80] Thessalonica, ruled by Manuel II Palaiologos (r. 1391–1425) itself surrendered after a lengthy siege in 1383–1387, along with most of eastern and central Macedonia, to the forces of Sultan Murad I.[81] Initially, the surrendered cities were allowed complete autonomy in exchange for payment of the kharaj poll-tax. Following the death of Emperor John V Palaiologos in 1391, however, Manuel II escaped Ottoman custody and went to Constantinople, where he was crowned emperor, succeeding his father. This angered Sultan Bayezid I, who laid waste to the remaining Byzantine territories, and then turned on Chrysopolis, which was captured by storm and largely destroyed.[82] Thessalonica too submitted again to Ottoman rule at this time, possibly after brief resistance, but was treated more leniently: although the city was brought under full Ottoman control, the Christian population and the Church retained most of their possessions, and the city retained its institutions.[83][84]

Thessalonica remained in Ottoman hands until 1403, when Emperor Manuel II sided with Bayezid’s eldest son Süleyman in the Ottoman succession struggle that broke out following the crushing defeat and capture of Bayezid at the Battle of Ankara against Tamerlane in 1402. In exchange for his support, in the Treaty of Gallipoli the Byzantine emperor secured the return of Thessalonica, part of its hinterland, the Chalcidice peninsula, and the coastal region between the rivers Strymon and Pineios.[85][86] Thessalonica and the surrounding region were given as an autonomous appanage to John VII Palaiologos. After his death in 1408, he was succeeded by Manuel’s third son, the Despot Andronikos Palaiologos, who was supervised by Demetrios Leontares until 1415. Thessalonica enjoyed a period of relative peace and prosperity after 1403, as the Turks were preoccupied with their own civil war, but was attacked by the rival Ottoman pretenders in 1412 (by Musa Çelebi[87]) and 1416 (during the uprising of Mustafa Çelebi against Mehmed I[88]).[89][90] Once the Ottoman civil war ended, the Turkish pressure on the city began to increase again. Just as during the 1383–1387 siege, this led to a sharp division of opinion within the city between factions supporting resistance, if necessary with Western help, or submission to the Ottomans.[91]

In 1423, Despot Andronikos Palaiologos ceded it to the Republic of Venice with the hope that it could be protected from the Ottomans who were besieging the city. The Venetians held Thessaloniki until it was captured by the Ottoman Sultan Murad II on 29 March 1430.[92]

Ottoman period[edit]

Hot chamber of the men’s baths in the Bey Hamam (1444)

When Sultan Murad II captured Thessaloniki and sacked it in 1430,[93] contemporary reports estimated that about one-fifth of the city’s population was enslaved.[94] Ottoman artillery was used to secure the city’s capture and bypass its double walls.[93] Upon the conquest of Thessaloniki, some of its inhabitants escaped,[95] including intellectuals such as Theodorus Gaza «Thessalonicensis» and Andronicus Callistus.[96] However, the change of sovereignty from the Byzantine Empire to the Ottoman one did not affect the city’s prestige as a major imperial city and trading hub.[97][98] Thessaloniki and Smyrna, although smaller in size than Constantinople, were the Ottoman Empire’s most important trading hubs.[97] Thessaloniki’s importance was mostly in the field of shipping,[97] but also in manufacturing,[98] while most of the city’s trade was controlled by Jewish people.[97]

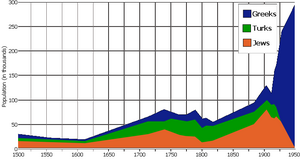

Demographics of Thessaloniki between 1500 and 1950[99]

During the Ottoman period, the city’s population of Ottoman Muslims (including those of Turkish origin, as well as Albanian Muslim, Bulgarian Muslim, especially the Pomaks and Greek Muslim of convert origin) and Muslim Roma like the Sepečides Romani grew substantially. According to the 1478 census Selânik (Ottoman Turkish: سلانیك), as the city came to be known in Ottoman Turkish, had 6,094 Christian Orthodox households, 4,320 Muslim ones, and some Catholic. No Jews were recorded in the census suggesting that the subsequent influx of Jewish population was not linked[100] to the already existing Romaniots community.[101] Soon after the turn of the 15th to 16th century, however, nearly 20,000 Sephardic Jews immigrated to Greece from the Iberian Peninsula following their expulsion from Spain by the 1492 Alhambra Decree.[102] By c. 1500, the number of households had grown to 7,986 Christian ones, 8,575 Muslim ones, and 3,770 Jewish. By 1519, Sephardic Jewish households numbered 15,715, 54% of the city’s population. Some historians consider the Ottoman regime’s invitation to Jewish settlement was a strategy to prevent the Christian population from dominating the city.[103] The city became both the largest Jewish city in the world and the only Jewish majority city in the world in the 16th century. As a result, Thessaloniki attracted persecuted Jews from all over the world.[104]

Thessaloniki was the capital of the Sanjak of Selanik within the wider Rumeli Eyalet (Balkans)[105] until 1826, and subsequently the capital of Selanik Eyalet (after 1867, the Selanik Vilayet).[106][107] This consisted of the sanjaks of Selanik, Serres and Drama between 1826 and 1912.[108]

With the break out of the Greek War of Independence in the spring of 1821, the governor Yusuf Bey imprisoned in his headquarters more than 400 hostages. On 18 May, when Yusuf learned of the insurrection to the villages of Chalkidiki, he ordered half of his hostages to be slaughtered before his eyes. The mulla of Thessaloniki, Hayrıülah, gives the following description of Yusuf’s retaliations: «Every day and every night you hear nothing in the streets of Thessaloniki but shouting and moaning. It seems that Yusuf Bey, the Yeniceri Agasi, the Subaşı, the hocas and the ulemas have all gone raving mad.»[109] It would take until the end of the century for the city’s Greek community to recover.[110]

Thessaloniki was also a Janissary stronghold where novice Janissaries were trained. In June 1826, regular Ottoman soldiers attacked and destroyed the Janissary base in Thessaloniki while also killing over 10,000 Janissaries, an event known as The Auspicious Incident in Ottoman history.[111] In 1870–1917, driven by economic growth, the city’s population expanded by 70%, reaching 135,000 in 1917.[112]

The last few decades of Ottoman control over the city were an era of revival, particularly in terms of the city’s infrastructure. It was at that time that the Ottoman administration of the city acquired an «official» face with the creation of the Government House[113] while a number of new public buildings were built in the eclectic style in order to project the European face both of Thessaloniki and the Ottoman Empire.[113][114] The city walls were torn down between 1869 and 1889,[115] efforts for a planned expansion of the city are evident as early as 1879,[116] the first tram service started in 1888[117] and the city streets were illuminated with electric lamp posts in 1908.[118] In 1888, the Oriental Railway connected Thessaloniki to Central Europe via rail through Belgrade and to Monastir in 1893, while the Thessaloniki-Istanbul Junction Railway connected it to Constantinople in 1896.[116]

20th century and beyond[edit]

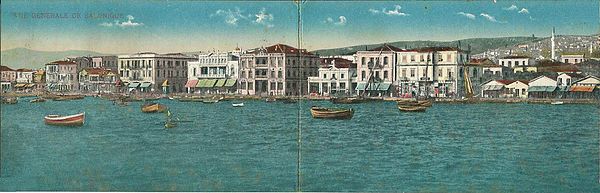

The seafront of Thessaloniki, as it was in 1917

In the early 20th century, Thessaloniki was in the centre of radical activities by various groups; the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, founded in 1897,[119] and the Greek Macedonian Committee, founded in 1903.[120] In 1903, an anarchist group known as the Boatmen of Thessaloniki planted bombs in several buildings in Thessaloniki, including the Ottoman Bank, with some assistance from the IMRO. The Greek consulate in Ottoman Thessaloniki (now the Museum of the Macedonian Struggle) served as the centre of operations for the Greek guerillas.

During this period, and since the 16th century, Thessaloniki’s Jewish element was the most dominant; it was the only city in Europe where the Jews were a majority of the total population.[121] The city was ethnically diverse and cosmopolitan. In 1890, its population had risen to 118,000, 47% of which were Jews, followed by Turks (22%), Greeks (14%), Bulgarians (8%), Roma (2%), and others (7%).[122] By 1913, the ethnic composition of the city had changed so that the population stood at 157,889, with Jews at 39%, followed again by Turks (29%), Greeks (25%), Bulgarians (4%), Roma (2%), and others at 1%.[123] Many varied religions were practiced and many languages spoken, including Judeo-Spanish, a dialect of Spanish spoken by the city’s Jews.

Thessaloniki was also the centre of activities of the Young Turks, a political reform movement, which goal was to replace the Ottoman Empire’s absolute monarchy with a constitutional government. The Young Turks started out as an underground movement, until finally in 1908, they started the Young Turk Revolution from the city of Thessaloniki, which lead to of them gaining control over the Ottoman Empire and put an end to the Ottoman sultans power.[124] Eleftherias (Liberty) Square, where the Young Turks gathered at the outbreak of the revolution, is named after the event.[125] Turkey’s first president Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who was born and raised in Thessaloniki, was a member of the Young Turks in his soldier days and also partook in the Young Turk Revolution.

Allied armies in Thessaloniki, World War I

As the First Balkan War broke out, Greece declared war on the Ottoman Empire and expanded its borders. When Eleftherios Venizelos, Prime Minister at the time, was asked if the Greek army should move towards Thessaloniki or Monastir (now Bitola, Republic of North Macedonia), Venizelos replied «Θεσσαλονίκη με κάθε κόστος!» (Thessaloniki, at all costs!).[126] As both Greece and Bulgaria wanted Thessaloniki, the Ottoman garrison of the city entered negotiations with both armies.[127] On 8 November 1912 (26 October Old Style), the feast day of the city’s patron saint, Saint Demetrius, the Greek Army accepted the surrender of the Ottoman garrison at Thessaloniki.[128] The Bulgarian army arrived one day after the surrender of the city to Greece and Tahsin Pasha, ruler of the city, told the Bulgarian officials that «I have only one Thessaloniki, which I have surrendered».[127] After the Second Balkan War, Thessaloniki and the rest of the Greek portion of Macedonia were officially annexed to Greece by the Treaty of Bucharest in 1913.[129] On 18 March 1913 George I of Greece was assassinated in the city by Alexandros Schinas.[130]

In 1915, during World War I, a large Allied expeditionary force established a base at Thessaloniki for operations[131] against pro-German Bulgaria.[132] This culminated in the establishment of the Macedonian Front, also known as the Salonika front.[133][134] And a temporary hospital run by the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service was set up in a disused factory. In 1916, pro-Venizelist Greek army officers and civilians, with the support of the Allies, launched an uprising,[135] creating a pro-Allied[136] temporary government by the name of the «Provisional Government of National Defence»[135][137] that controlled the «New Lands» (lands that were gained by Greece in the Balkan Wars, most of Northern Greece including Greek Macedonia, the North Aegean as well as the island of Crete);[135][137] the official government of the King in Athens, the «State of Athens»,[135] controlled «Old Greece»[135][137] which were traditionally monarchist. The State of Thessaloniki was disestablished with the unification of the two opposing Greek governments under Venizelos, following the abdication of King Constantine in 1917.[132][137]

On 30 December 1915 an Austrian air raid on Thessaloniki alarmed many town civilians and killed at least one person, and in response the Allied troops based there arrested the German, Austrian, Bulgarian and Turkish vice-consuls and their families and dependents and put them on a battleship, and billeted troops in their consulate buildings in Thessaloniki.[138]

Most of the old centre of the city was destroyed by the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, which was started accidentally by an unattended kitchen fire on 18 August 1917.[139] The fire swept through the centre of the city, leaving 72,000 people homeless; according to the Pallis Report, most of them were Jewish (50,000). Many businesses were destroyed, as a result, 70% of the population were unemployed.[139] Two churches and many synagogues and mosques were lost. More than one quarter of the total population of approximately 271,157 became homeless.[139] Following the fire the government prohibited quick rebuilding, so it could implement the new redesign of the city according to the European-style urban plan[9] prepared by a group of architects, including the Briton Thomas Mawson, and headed by French architect Ernest Hébrard.[139] Property values fell from 6.5 million Greek drachmas to 750,000.[140]

After the defeat of Greece in the Greco-Turkish War and during the break-up of the Ottoman Empire, a population exchange took place between Greece and Turkey.[136] Over 160,000 ethnic Greeks deported from the former Ottoman Empire – particularly Greeks from Asia Minor[141] and East Thrace were resettled in the city,[136] changing its demographics. Additionally many of the city’s Muslims, including Ottoman Greek Muslims, were deported to Turkey, ranging at about 20,000 people.[142] This made the Greek element dominant,[143] while the Jewish population was reduced to a minority for the first time since the 14th century.[144]

During World War II Thessaloniki was heavily bombarded by Fascist Italy (with 232 people dead, 871 wounded and over 800 buildings damaged or destroyed in November 1940 alone),[146] and, the Italians having failed in their invasion of Greece, it fell to the forces of Nazi Germany on 8 April 1941[147] and went under German occupation. The Nazis soon forced the Jewish residents into a ghetto near the railroads and on 15 March 1943 began the deportation of the city’s Jews to Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen concentration camps.[148][149][150] Most were immediately murdered in the gas chambers. Of the 45,000 Jews deported to Auschwitz, only 4% survived.[151][152]

Indian troops sweep for mines in Salonika, 1944.

During a speech in Reichstag, Hitler claimed that the intention of his Balkan campaign, was to prevent the Allies from establishing «a new Macedonian front», as they had during WWI. The importance of Thessaloniki to Nazi Germany can be demonstrated by the fact that, initially, Hitler had planned to incorporate it directly into Nazi Germany[153] and not have it controlled by a puppet state such as the Hellenic State or an ally of Germany (Thessaloniki had been promised to Yugoslavia as a reward for joining the Axis on 25 March 1941).[154]

As it was the first major city in Greece to fall to the occupying forces, the first Greek resistance group formed in Thessaloniki (under the name Ελευθερία, Elefthería, «Freedom»)[155] as well as the first anti-Nazi newspaper in an occupied territory anywhere in Europe,[156] also by the name Eleftheria. Thessaloniki was also home to a military camp-converted-concentration camp, known in German as «Konzentrationslager Pavlo Mela» (Pavlos Melas Concentration Camp),[157] where members of the resistance and other anti-fascists[157] were held either to be killed or sent to other concentration camps.[157] On 30 October 1944, after battles with the retreating German army and the Security Battalions of Poulos, forces of ELAS entered Thessaloniki as liberators headed by Markos Vafiadis (who did not obey orders from ELAS leadership in Athens to not enter the city). Pro-EAM celebrations and demonstrations followed in the city.[158][159] In the 1946 monarchy referendum, the majority of the locals voted in favor of a republic, contrary to the rest of Greece.[160]

After the war, Thessaloniki was rebuilt with large-scale development of new infrastructure and industry throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Many of its architectural treasures still remain, adding value to the city as a tourist destination, while several early Christian and Byzantine monuments of Thessaloniki were added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1988.[161] In 1997, Thessaloniki was celebrated as the European Capital of Culture,[162] sponsoring events across the city and the region. Agency established to oversee the cultural activities of that year 1997 was still in existence by 2010.[163] In 2004, the city hosted a number of the football events as part of the 2004 Summer Olympics.[164]

Today, Thessaloniki has become one of the most important trade and business hubs in Southeastern Europe, with its port, the Port of Thessaloniki being one of the largest in the Aegean and facilitating trade throughout the Balkan hinterland.[11] On 26 October 2012 the city celebrated its centennial since its incorporation into Greece.[165] The city also forms one of the largest student centers in Southeastern Europe, is host to the largest student population in Greece and was the European Youth Capital in 2014.[14][166]

Geography[edit]

Thessaloniki is located 502 kilometres (312 mi) north of Athens.

Thessaloniki’s urban area spreads over 30 kilometres (19 mi) from Oraiokastro in the north to Thermi in the south in the direction of Chalkidiki.

Geology[edit]

Thessaloniki lies on the northern fringe of the Thermaic Gulf on its eastern coast and is bound by Mount Chortiatis on its southeast. Its proximity to imposing mountain ranges, hills and fault lines, especially towards its southeast have historically made the city prone to geological changes.

Since medieval times, Thessaloniki has been hit by strong earthquakes, notably in 1759, 1902, 1978 and 1995.[167] On 19–20 June 1978, the city suffered a series of powerful earthquakes, registering 5.5 and 6.5 on the Richter scale.[168][169] The tremors caused considerable damage to a number of buildings and ancient monuments,[168] but the city withstood the catastrophe without any major problems.[169] One apartment building in central Thessaloniki collapsed during the second earthquake, killing many and raising the final death toll to 51.[168][169]

Climate[edit]

Thessaloniki’s climate is directly affected by the Aegean Sea, on which it is situated.[170] The city lies in a transitional climatic zone, so its climate displays characteristics of several climates. According to the Köppen climate classification, the city has a Mediterranean climate (Csa), bordering on a semi-arid climate (BSh), observed on the periphery of the region. Its average annual precipitation of 450 mm (17.7 inches) is due to the Pindus rain shadow drying the westerly winds. However, the city has a summer precipitation between 20 to 30 mm (0.79 to 1.18 inches), which increases gradually towards the north and west, turning some parts of the city humid subtropical (Cfa).[171]

Winters are somewhat dry, with common morning frost. Snowfalls occur sporadically more or less every winter, but the snow cover does not last for more than a few days. Fog is common, with an average of 193 foggy days in a year.[172] During the coldest winters, temperatures can drop to −10 °C (14 °F).[172] The record minimum temperature in Thessaloniki was −14 °C (7 °F).[173] On average, Thessaloniki experiences frost (sub-zero temperature) 32 days a year.[172] The coldest month of the year in the city is January, with an average 24-hour temperature of 5 °C (41 °F).[174] Wind is also usual in the winter months, with December and January having an average wind speed of 26 km/h (16 mph).[172]

Thessaloniki’s summers are hot and quite dry.[172] Maximum temperatures usually rise above 30 °C (86 °F),[172] but they rarely approach or go over 40 °C (104 °F);[172] the average number of days the temperature is above 32 °C (90 °F) is 32.[172] The maximum recorded temperature in the city was 44 °C (111 °F).[172][173] Rain seldom falls in summer, mainly during thunderstorms. In the summer months Thessaloniki also experiences strong heat waves.[175] The hottest month of the year in the city is July, with an average 24-hour temperature of 26 °C (79 °F).[174]

In 2021, Greece was taken to task by the European Commission for failing to curb consistently high air pollution levels in Thessaloniki.[176]

| Climate data for Thessaloniki Airport HNMS 1959-2010 Elevation: 2m (extremes 1963–2019) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.0 (73.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

32.0 (89.6) |

31.0 (87.8) |

36.0 (96.8) |

41.4 (106.5) |

44.0 (111.2) |

40.5 (104.9) |

37.3 (99.1) |

32.2 (90.0) |

27.0 (80.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

44.0 (111.2) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

14.3 (57.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

24.6 (76.3) |

29.4 (84.9) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.4 (88.5) |

27.1 (80.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

10.9 (51.6) |

20.5 (68.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

6.8 (44.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

14.3 (57.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

24.7 (76.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

26.4 (79.5) |

21.9 (71.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7 (45) |

15.9 (60.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

2.3 (36.1) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.9 (46.2) |

12.6 (54.7) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

19.1 (66.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.3 (52.3) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.2 (37.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.2 (6.4) |

−10.0 (14.0) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

2.8 (37.0) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

3.0 (37.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

−6.2 (20.8) |

−9.8 (14.4) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 37.7 (1.48) |

35 (1.4) |

37.9 (1.49) |

36.1 (1.42) |

44.2 (1.74) |

29.8 (1.17) |

23.8 (0.94) |

19.3 (0.76) |

29.8 (1.17) |

43.0 (1.69) |

52.8 (2.08) |

55.1 (2.17) |

444.5 (17.51) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.5 | 10.7 | 12.1 | 11.1 | 11.0 | 7.9 | 6.7 | 5.1 | 7.0 | 9.3 | 11.0 | 12.7 | 116.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75.7 | 72.0 | 71 | 67.3 | 63.0 | 55.4 | 52.7 | 55.0 | 61.9 | 70.4 | 76.3 | 77.9 | 66.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 98.7 | 102.6 | 147.2 | 202.6 | 252.7 | 296.4 | 325.7 | 295.8 | 229.9 | 165.5 | 117.8 | 102.6 | 2,337.5 |

| Source: [1] [2] Sunshine Hours WMO [3] |

| Climate data for Downtown Thessaloniki (Mar 2005-Jan 2023) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 10.9 (51.6) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.3 (59.5) |

19.3 (66.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

28.9 (84.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.4 (88.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

21.3 (70.3) |

16.9 (62.4) |

12.5 (54.5) |

21.0 (69.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.2 (46.8) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

20.9 (69.6) |

25.2 (77.4) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

23.6 (74.5) |

18.4 (65.1) |

14.2 (57.6) |

9.9 (49.8) |

17.8 (64.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) |

6.9 (44.4) |

8.9 (48.0) |

12.5 (54.5) |

17.3 (63.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.2 (75.6) |

20.2 (68.4) |

15.5 (59.9) |

11.5 (52.7) |

7.2 (45.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 39.8 (1.57) |

29.3 (1.15) |

39.1 (1.54) |

31.9 (1.26) |

27.1 (1.07) |

40.1 (1.58) |

28.4 (1.12) |

41.0 (1.61) |

40.8 (1.61) |

22.9 (0.90) |

22.5 (0.89) |

37.5 (1.48) |

400.4 (15.78) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 131.6 | 125.6 | 179.2 | 226.4 | 277.6 | 311.2 | 359.2 | 334.3 | 249.7 | 184.7 | 129.5 | 122.7 | 2,631.7 |

| Source: [4] |

Government[edit]

According to the Kallikratis reform, as of 1 January 2011 the Thessaloniki Urban Area (Greek: Πολεοδομικό Συγκρότημα Θεσσαλονίκης) which makes up the «City of Thessaloniki», is made up of six self-governing municipalities (Greek: Δήμοι) and one municipal unit (Greek: Δημοτική ενότητα). The municipalities that are included in the Thessaloniki Urban Area are those of Thessaloniki (the city centre and largest in population size), Kalamaria, Neapoli-Sykies, Pavlos Melas, Kordelio-Evosmos, Ampelokipoi-Menemeni, and the municipal units of Pylaia and Panorama, part of the municipality of Pylaia-Chortiatis.[3] Prior to the Kallikratis reform, the Thessaloniki Urban Area was made up of twice as many municipalities, considerably smaller in size, which created bureaucratic problems.[177]

Thessaloniki Municipality[edit]

The municipality of Thessaloniki (Greek: Δήμος Θεσαλονίκης) is the second most populous in Greece, after Athens, with a resident population of 317,778[4] (in 2021) and an area of 19.307 square kilometres (7.454 square miles). The municipality forms the core of the Thessaloniki Urban Area, with its central district (the city centre), referred to as the Kentro, meaning ‘centre’ or ‘downtown’.[178]

The city’s first mayor, Osman Sait Bey, was appointed when the institution of mayor was inaugurated under the Ottoman Empire in 1912. The incumbent mayor is Konstantinos Zervas. In 2011, the municipality of Thessaloniki had a budget of €464.33 million[179] while the budget of 2012 stands at €409.00 million.[180]

Other[edit]

Thessaloniki is the second largest city in Greece. It is an influential city for the northern parts of the country and is the capital of the region of Central Macedonia and the Thessaloniki regional unit. The Ministry of Macedonia and Thrace is also based in Thessaloniki, since the city is the de facto capital of the Greek region of Macedonia.[citation needed]

It is customary every year for the Prime Minister of Greece to announce his administration’s policies on a number of issues, such as the economy, at the opening night of the Thessaloniki International Fair. In 2010, during the first months of the 2010 Greek debt crisis, the entire cabinet of Greece met in Thessaloniki to discuss the country’s future.[181]

In the Hellenic Parliament, the Thessaloniki urban area constitutes a 16-seat constituency. As of the 2019 Greek legislative election the largest party in Thessaloniki is the New Democracy with 35.55% of the vote, followed by the Coalition of the Radical Left (31.29%) and the Movement for Change (6.05%).[182] The table below summarizes the results of the latest elections.

| Party | Votes | % | Shift | MPs (16) | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Democracy | 107,607 | 35.55% |

7 / 16 (44%) |

||

| Coalition of the Radical Left | 94,697 | 31.29% |

5 / 16 (31%) |

||

| Movement for Change | 18,313 | 6.05% |

1 / 16 (6%) |

||

| Greek Solution | 16,272 | 5.38% |

1 / 16 (6%) |

||

| Communist Party of Greece | 16,028 | 5.30% |

1 / 16 (6%) |

||

| MeRA25 | 14,379 | 4.75% |

1 / 16 (6%) |

||

| Other parties (unrepresented) | 35,364 | 11.68% |

Cityscape[edit]

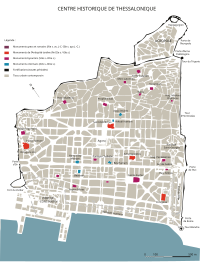

Plan for central Thessaloniki by Ernest Hébrard. Much of the plan can be seen in today’s city centre.

Architecture[edit]

Architecture in Thessaloniki is the direct result of the city’s position at the centre of all historical developments in the Balkans. Aside from its commercial importance, Thessaloniki was also for many centuries the military and administrative hub of the region, and beyond this the transportation link between Europe and the Levant.

Merchants, traders and refugees from all over Europe settled in the city. The need for commercial and public buildings in this new era of prosperity led to the construction of large edifices in the city centre. During this time, the city saw the building of banks, large hotels, theatres, warehouses, and factories. Architects who designed some of the most notable buildings of the city, in the late 19th and early 20th century, include Vitaliano Poselli, Pietro Arrigoni, Xenophon Paionidis, Salvatore Poselli, Leonardo Gennari, Eli Modiano, Moshé Jacques, Joseph Pleyber, Frederic Charnot, Ernst Ziller, Max Rubens, Filimon Paionidis, Dimitris Andronikos, Levi Ernst, Angelos Siagas, Alexandros Tzonis and more, using mainly the styles of Eclecticism, Art Nouveau and Neobaroque.

The city layout changed after 1870, when the seaside fortifications gave way to extensive piers, and many of the oldest walls of the city were demolished, including those surrounding the White Tower, which today stands as the main landmark of the city. As parts of the early Byzantine walls were demolished, this allowed the city to expand east and west along the coast.[183]

The expansion of Eleftherias Square towards the sea completed the new commercial hub of the city and at the time was considered one of the most vibrant squares of the city. As the city grew, workers moved to the western districts, because of their proximity to factories and industrial activities; while the middle and upper classes gradually moved from the city-centre to the eastern suburbs, leaving mainly businesses. In 1917, a devastating fire swept through the city and burned uncontrollably for 32 hours.[112] It destroyed the city’s historic centre and a large part of its architectural heritage, but paved the way for modern development featuring wider diagonal avenues and monumental squares.[112][184]

City centre[edit]

After the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, a team of architects and urban planners including Thomas Mawson and Ernest Hebrard, a French architect, chose the Byzantine era as the basis of their (re)building designs for Thessaloniki’s city centre. The new city plan included axes, diagonal streets and monumental squares, with a street grid that would channel traffic smoothly. The plan of 1917 included provisions for future population expansions and a street and road network that would be, and still is sufficient today.[112] It contained sites for public buildings and provided for the restoration of Byzantine churches and Ottoman mosques.

Also called the historic centre, it is divided into several districts, including Dimokratias Square (Democracy Sq. known also as Vardaris) Ladadika (where many entertainment venues and tavernas are located), Kapani (where the city’s central Modiano market is located), Diagonios, Navarinou, Rotonda, Agia Sofia and Hippodromio, which are all located around Thessaloniki’s most central point, Aristotelous Square.

Various commercial stoas around Aristotelous are named from the city’s past and historic personalities of the city, like stoa Hirsch, stoa Carasso/Ermou, Pelosov, Colombou, Levi, Modiano, Morpurgo, Mordoch, Simcha, Kastoria, Malakopi, Olympios, Emboron, Rogoti, Vyzantio, Tatti, Agiou Mina, Karipi etc.[185]

The western portion of the city centre is home to Thessaloniki’s law courts, its central international railway station and the port, while its eastern side hosts the city’s two universities, the Thessaloniki International Exhibition Centre, the city’s main stadium, its archaeological and Byzantine museums, the new city hall and its central parks and gardens, namely those of the ΧΑΝΘ and Pedion tou Areos.

Ano Poli[edit]

Ano Poli (also called Old Town and literally the Upper Town) is the heritage listed district north of Thessaloniki’s city centre that was not engulfed by the great fire of 1917 and was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site by ministerial actions of Melina Merkouri, during the 1980s. It consists of Thessaloniki’s most traditional part of the city, still featuring small stone paved streets, old squares and homes featuring old Greek and Ottoman architecture. It is the favourite area of Thessaloniki’s poets, intellectuals and bohemians.

Panorama of the city from Ano Poli

Ano Poli is also the highest point in Thessaloniki and as such, is the location of the city’s acropolis, its Byzantine fort, the Heptapyrgion, a large portion of the city’s remaining walls, and with many of its additional Ottoman and Byzantine structures still standing. With the capture of Thessaloniki by the Ottomans in 1430, after a lengthy siege of the city from 1422 to 1430, the Ottomans settled in Ano Poli. This geographical choice was attributed to the higher level of Ano Poli, which was convenient to control the rest of the population remotely, and the microclimate of the area, which favoured better living conditions in terms of hygiene compared to the areas of the centre.

Today, the area provides access to the Seich Sou Forest National Park[186] and features panoramic views of the whole city and the Thermaic Gulf. On clear days Mount Olympus, at about 100 km (62 mi) away across the gulf, can also be seen towering the horizon.

Other districts of Thessaloniki Municipality[edit]

In the Municipality of Thessaloniki, in addition to the historic centre and the Upper Town, are included the following districts: Xirokrini, Dikastiria (Courts), Ichthioskala, Palaios Stathmos, Lachanokipoi, Behtsinari, Panagia Faneromeni, Doxa, Saranta Ekklisies, Evangelistria, Triandria, Agia Triada-Faliro, Ippokrateio, Charilaou, Analipsi, Depot and Toumba.

In the area of the Old Railway Station (Palaios Stathmos) began the construction of the Holocaust Museum of Greece.[187][188] In this area are located the Railway Museum of Thessaloniki, the Water Supply Museum and large entertainment venues of the city, such as Milos, Fix, Vilka (which are housed in converted old factories). The New Thessaloniki Railway Station is located on Monastiriou street.

Other extended and densely built-up residential areas are Charilaou and Toumba, which is divided into «Ano Toumpa» and «Kato Toumpa». Toumba was named after the homonymous hill of Toumba, where extensive archaeological research takes place. It was created by refugees after the 1922 Asia Minor disaster and the population exchange (1923–24).

On Exochon avenue (Rue des Campagnes, today Vasilissis Olgas and Vasileos Georgiou Avenues), was up until the 1920s home to the city’s most affluent residents and formed the outermost suburbs of the city at the time, with the area close to the Thermaic Gulf, from the 19th-century holiday villas which defined the area.[189][190]

Thessaloniki urban area[edit]

Other districts of the wider urban area of Thessaloniki are Ampelokipi, Eleftherio — Kordelio, Menemeni, Evosmos, Ilioupoli, Stavroupoli, Nikopoli, Neapoli, Polichni, Paeglos, Meteora, Agios Pavlos, Kalamaria, Pylaia and the Sykies.

Northwestern Thessaloniki is home to Moni Lazariston, located in Stavroupoli, which today forms one of the most important cultural centres for the city, including MOMus–Museum of Modern Art–Costakis Collection and two theatres of the National Theatre of Northern Greece.[191][192]

In northwestern Thessaloniki many cultural premises exist, such as the open-air Theater Manos Katrakis in Sykies, the Museum of Refugee Hellenism in Neapolis, the municipal theatre and the open-air theatre in Neapoli and the New Cultural Centre of Menemeni (Ellis Alexiou Street).[193] The Stavroupolis Botanical Garden on Perikleous Street includes 1,000 species of plants and is a 5-acre (2.0 ha) oasis of greenery. The Environmental Education Centre in Kordelio was designed in 1997 and is one of a few public buildings of bioclimatic design in Thessaloniki.[194]

Northwest Thessaloniki forms the main entry point into the city of Thessaloniki with the avenues of Monastiriou, Lagkada and 26is Octovriou passing through it, as well as the extension of the A1 motorway, feeding into Thessaloniki’s city centre. The area is home to the Macedonia InterCity Bus Terminal (KTEL), the New Thessaloniki Railway Station, the Zeitenlik Allied memorial military cemetery.

Monuments have also been erected in honour of the fighters of the Greek Resistance, as in these areas the Resistance was very active: the monument of Greek National Resistance in Sykies, the monument of Greek National Resistance in Stavroupolis, the Statue of the struggling Mother in Eptalofos Square and the monument of the young Greeks who were executed by the Nazis on 11 May 1944 in Xirokrini. In Eptalofos, on 15 May 1941, one month after the occupation of the country, the first resistance organization in Greece, «Eleftheria», was founded, with its newspaper and the first illegal printing house in the city of Thessaloniki.[195][196]

Today southeastern Thessaloniki has in some way become an extension of the city centre, with the avenues of Megalou Alexandrou, Georgiou Papandreou (Antheon), Vasileos Georgiou, Vasilissis Olgas, Delfon, Konstantinou Karamanli (Nea Egnatia) and Papanastasiou passing through it, enclosing an area traditionally called Ντεπώ (Depó, lit. Dépôt), from the name of the old tram station, owned by a French company.

The municipality of Kalamaria is also located in southeastern Thessaloniki and was firstly, inhabited mainly by Greek refugees from Asia Minor and East Thrace after 1922.[197] There are built the Northern Greece Naval Command and the old royal palace (called Palataki), located on the most westerly point of Mikro Emvolo cape.

Paleochristian and Byzantine monuments (UNESCO)[edit]

The church of Saint Demetrius, patron saint of the city, built in the fourth century, is the largest basilica in Greece and one of the city’s most prominent Paleochristian monuments.

Panagia Chalkeon church in Thessaloniki (1028 AD), one of the 15 UNESCO World Heritage Sites in the city

Because of Thessaloniki’s importance during the early Christian and Byzantine periods, the city is host to several paleochristian monuments that have significantly contributed to the development of Byzantine art and architecture throughout the Byzantine Empire as well as Serbia.[161] The evolution of Imperial Byzantine architecture and the prosperity of Thessaloniki go hand in hand, especially during the first years of the Empire,[161] when the city continued to flourish. It was at that time that the Complex of Roman emperor Galerius was built, as well as the first church of Hagios Demetrios.[161]

By the eighth century, the city had become an important administrative centre of the Byzantine Empire, and handled much of the Empire’s Balkan affairs.[198] During that time, the city saw the creation of more notable Christian churches that are now part of Thessaloniki’s UNESCO World Heritage Site, such as the Church of Saint Catherine, the Hagia Sophia of Thessaloniki, the Church of the Acheiropoietos, the Church of Panagia Chalkeon.[161] When the Ottoman Empire took control of Thessaloniki in 1430, most of the city’s churches were converted into mosques,[161] but have survived to this day. Travellers such as Paul Lucas and Abdulmejid I[161] document the city’s wealth in Christian monuments during the years of Ottoman control of the city.

The church of Hagios Demetrios burned down during the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, as did many other city monuments, but it was rebuilt. During World War II, the city was extensively bombed and as such many of Thessaloniki’s paleochristian and Byzantine monuments were heavily damaged.[198] Some of the sites were not restored until the 1980s. Thessaloniki has more monuments listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site than any other city in Greece, a total of 15 monuments.[161] They have been listed since 1988.[161]

Urban sculpture[edit]

There are around 150 statues or busts in the city.[199] Probably the most famous one is the equestrian statue of Alexander the Great on the promenade, placed in 1973 and created by sculptor Evangelos Moustakas. An equestrian statue of Constantine I, by sculptor Georgios Dimitriades, is located in Demokratias Square. Other notable statues include that of Eleftherios Venizelos by sculptor Giannis Pappas, Pavlos Melas by Natalia Mela, the statue of Emmanouel Pappas by Memos Makris, Chrysostomos of Smyrna by Athanasios Apartis, such as various creations by George Zongolopoulos.

Thessaloniki 2012 Programme[edit]

Aerial view of the newest section of the promenade (Nea Paralia), which was opened to the public in January 2014

With the 100th anniversary of the 1912 incorporation of Thessaloniki into Greece, the government announced a large-scale redevelopment programme for the city of Thessaloniki, which aims in addressing the current environmental and spatial problems[200] that the city faces. More specifically, the programme will drastically change the physiognomy of the city[200] by relocating the Thessaloniki International Exhibition Centre and grounds of the Thessaloniki International Fair outside the city centre and turning the current location into a large metropolitan park,[201] redeveloping the coastal front of the city,[201] relocating the city’s numerous military camps and using the grounds and facilities to create large parklands and cultural centres;[201] and the complete redevelopment of the harbour and the Lachanokipoi and Dendropotamos districts (behind and near the Port of Thessaloniki) into a commercial business district,[201] with possible highrise developments.[202]

The plan also envisions the creation of new wide avenues in the outskirts of the city[201] and the creation of pedestrian-only zones in the city centre.[201] Furthermore, the program includes plans to expand the jurisdiction of Seich Sou Forest National Park[200] and the improvement of accessibility to and from the Old Town.[200] The ministry has said that the project will take an estimated 15 years to be completed, in 2025.[201]

Part of the plan has been implemented with extensive pedestrianisations within the city centre by the municipality of Thessaloniki and the revitalisation the eastern urban waterfront/promenade, Νέα Παραλία (Néa Paralía, lit. new promenade), with a modern and vibrant design. Its first section opened in 2008, having been awarded as the best public project in Greece of the last five years by the Hellenic Institute of Architecture.[203]

The municipality of Thessaloniki’s budget for the reconstruction of important areas of the city and the completion of the waterfront, opened in January 2014, was estimated at €28.2 million (US$39.9 million) for the year 2011 alone.[204]

Economy[edit]

GDP of the Thessaloniki regional unit 2000–2011 |

|

| Statistics | |

|---|---|

| GDP | €19.851 billion (PPP, 2011)[205] |

| GDP rank | 2nd in Greece |

|

GDP growth |

-7.8% (2011)[205] |

|

GDP per capita |

€17,200 (PPP, 2011)[205] |

|

Labour force |

534,800 (2010)[206] |

| Unemployment | 30.2% (2014)[207] |

Thessaloniki rose to economic prominence as a major economic hub in the Balkans during the years of the Roman Empire. The Pax Romana and the city’s strategic position allowed for the facilitation of trade between Rome and Byzantium (later Constantinople and now Istanbul) through Thessaloniki by means of the Via Egnatia.[208] The Via Egnatia also functioned as an important line of communication between the Roman Empire and the nations of Asia,[208] particularly in relation to the Silk Road. With the partition of the Roman Emp. into East (Byzantine) and West, Thessaloniki became the second-largest city of the Eastern Roman Empire after New Rome (Constantinople) in terms of economic might.[52][208] Under the Empire, Thessaloniki was the largest port in the Balkans.[209] As the city passed from Byzantium to the Republic of Venice in 1423, it was subsequently conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Under Ottoman rule the city retained its position as the most important trading hub in the Balkans.[97] Manufacturing, shipping and trade were the most important components of the city’s economy during the Ottoman period,[97] and the majority of the city’s trade at the time was controlled by ethnic Greeks.[97] Plus, the Jewish community was also an important factor in the trade sector.[citation needed]

Historically important industries for the economy of Thessaloniki included tobacco (in 1946 35% of all tobacco companies in Greece were headquartered in the city, and 44% in 1979)[210] and banking (in Ottoman years Thessaloniki was a major centre for investment from western Europe, with the Banque de Salonique having a capital of 20 million French francs in 1909).[97]

Services[edit]

The service sector accounts for nearly two-thirds of the total labour force of Thessaloniki.[211] Of those working in services, 20% were employed in trade; 13% in education and healthcare; 7.1% in real estate; 6.3% in transport, communications and storage; 6.1% in the finance industry and service-providing organizations; 5.7% in public administration and insurance services; and 5.4% in hotels and restaurants.[211]

The city’s port, the Port of Thessaloniki, is one of the largest ports in the Aegean and as a free port, it functions as a major gateway to the Balkan hinterland.[11][212] In 2010, more than 15.8 million tons of products went through the city’s port,[213] making it the second-largest port in Greece after Aghioi Theodoroi, surpassing Piraeus. At 273,282 TEUs, it is also Greece’s second-largest container port after Piraeus.[214] As a result, the city is a major transportation hub for the whole of south-eastern Europe,[215] carrying, among other things, trade to and from the neighbouring countries.[citation needed]

In recent years Thessaloniki has begun to turn into a major port for cruising in the eastern Mediterranean.[212] The Greek ministry of tourism considers Thessaloniki to be Greece’s second most important commercial port,[216] and companies such as Royal Caribbean International have expressed interest in adding the Port of Thessaloniki to their destinations.[216] A total of 30 cruise ships are expected to arrive at Thessaloniki in 2011.[216]

The GDP of Thessaloniki in comparison to that of Attica and the rest of the country (2012)

Companies[edit]

- Recent history

After WWII and the Greek Civil War, heavy industrialization of the city’s suburbs began in the mid-1950s.[217]

During the 1980s, a spate of factory shutdowns occurred, mostly of automobile manufacturers, such as Agricola, AutoDiana, EBIAM, Motoemil, Pantelemidis-TITAN and C.AR. Since the 1990s, companies took advantage of cheaper labour markets and more lax regulations in other countries, and among the largest companies to shut down factories were Goodyear,[218] AVEZ pasta industry (one of the first industrial factories in northern Greece, built in 1926),[219] Philkeram Johnson, AGNO dairy and VIAMIL.

However, Thessaloniki still remains a major business hub in the Balkans and Greece, with a number of important Greek companies headquartered in the city, such as the Hellenic Vehicle Industry (ELVO), Namco, Astra Airlines, Ellinair, Pyramis and MLS Multimedia, which introduced the first Greek-built smartphone in 2012.[220]

- Industry

In early 1960s, with the collaboration of Standard Oil and ESSO-Pappas, a large industrial zone was created, containing refineries, oil refinery and steel production (owned by Hellenic Steel Co.). The zone attracted also a series of different factories during the next decades.

Titan Cement has also facilities outside the city, on the road to Serres,[221] such as the AGET Heracles, a member of the Lafarge group, and Alumil SA.

Multinational companies such as Air Liquide, Cyanamid, Nestlé, Pfizer, Coca-Cola Hellenic Bottling Company and Vivartia have also industrial facilities in the suburbs of the city.[222]

- Foodstuff

Foodstuff or drink companies headquartered in the city include the Macedonian Milk Industry (Mevgal), Allatini, Barbastathis, Hellenic Sugar Industry, Haitoglou Bros, Mythos Brewery, Malamatina, while the Goody’s chain started from the city.[citation needed]

The American Farm School also has important contribution in food production.[223]

Macroeconomic indicators[edit]

In 2011, the regional unit of Thessaloniki had a Gross Domestic Product of €18.293 billion (ranked second amongst the country’s regional units),[205] comparable to Bahrain or Cyprus, and a per capita of €15,900 (ranked 16th).[205] In Purchasing Power Parity, the same indicators are €19,851 billion (2nd)[205] and €17,200 (15th) respectively.[205] In terms of comparison with the European Union average, Thessaloniki’s GDP per capita indicator stands at 63% the EU average[205] and 69% in PPP[205] – this is comparable to the German state of Brandenburg.[205] Overall, Thessaloniki accounts for 8.9% of the total economy of Greece.[205] Between 1995 and 2008 Thessaloniki’s GDP saw an average growth rate of 4.1% per annum (ranging from +14.5% in 1996 to −11.1% in 2005) while in 2011 the economy contracted by −7.8%.[205]

Demographics[edit]

Historical ethnic statistics[edit]

The tables below show the ethnic statistics of Thessaloniki during the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

| Year | Total Population | Jewish | Turkish | Greek | Bulgarians | Roma | Other | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1890[123] | 118,000 | 100% | 55,000 | 47% | 39,000 | 22% | 28,000 | 14% | 14,000 | 8% | 5,500 | 2% | 8,500 | 7% |

| Around 1913[122] | 157,889 | 100% | 61,439 | 39% | 45,889 | 29% | 39,956 | 25% | 6,263 | 4% | 2,721 | 2% | 1,621 | 1% |

Population growth[edit]

| Year | Pop. |

|---|---|

| 100 | 200,000 |

| 1348 | 150,000 |

| 1453 | 40,000 |

| 1679 | 36,000 |

| 1842 | 70,000 |

| 1870 | 90,000 |

| 1882 | 85,000 |

| 1890 | 118,000 |

| 1902 | 126,000 |

| 1913 | 157,000 |

| 1917 | 230,000 |

| 1951 | 297,164 |

| 1961 | 377,026 |

| 1981 | 406,413 |

| 2001 | 954,027 |

| 2011 | 1,030,338 |

| 2021 | 1,091,424 |

| From 2001 on, data on the city’s metropolitan area. References:[58][112][224][225][226][227][228] |

The municipality of Thessaloniki is the most populous in the Thessaloniki Urban Area. Its population has increased in the latest census and the metropolitan area’s population rose to over one million. The city forms the base of the Thessaloniki metropolitan area, with latest census in 2021 giving it a population of 1,091,424.[224]

| Year | Municipality | Metropolitan area | rank |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 363,987[227] | 954,027[227] | |

| 2011 | 325,182[224] | 1,030,338[224] | |

| 2021 | 317,778[4] | 1,091,424[citation needed] |

Jews of Thessaloniki[edit]

Paths of Jewish immigration to the city

The Jewish population in Greece is the oldest in mainland Europe (see Romaniotes). When Paul the Apostle came to Thessaloniki, he taught in the area of what today is called Upper City. Later, during the Ottoman period, with the coming of Sephardic Jews from Spain, the community of Thessaloniki became mostly Sephardic. Thessaloniki became the largest centre in Europe of the Sephardic Jews, who nicknamed the city la madre de Israel (Israel’s mother)[149] and «Jerusalem of the Balkans».[229] It also included the historically significant and ancient Greek-speaking Romaniote community. During the Ottoman era, Thessaloniki’s Sephardic community was half of the population according to the Ottoman Census of 1902 and almost 40% the city’s population of 157,000 about 1913; Jewish merchants were prominent in commerce until the ethnic Greek population increased after Thessaloniki was incorporated into the Kingdom of Greece in 1913. By the 1680s, about 300 families of Sephardic Jews, followers of Sabbatai Zevi, had converted to Islam, becoming a sect known as the Dönmeh (convert), and migrated to Salonika, whose population was majority Jewish. They established an active community that thrived for about 250 years. Many of their descendants later became prominent in trade.[230] Many Jewish inhabitants of Thessaloniki spoke Judeo-Spanish, the Romance language of the Sephardic Jews.[231]

Jewish family of Salonika in 1917

From the second half of the 19th century with the Ottoman reforms, the Jewish community had a new revival. Many French and especially Italian Jews (from Livorno and other cities), influential in introducing new methods of education and developing new schools and intellectual environment for the Jewish population, were established in Thessaloniki. Such modernists introduced also new techniques and ideas from the industrialised Western Europe and from the 1880s the city began to industrialize. The Italian Jews Allatini brothers led Jewish entrepreneurship, establishing milling and other food industries, brickmaking and processing plants for tobacco. Several traders supported the introduction of a large textile-production industry, superseding the weaving of cloth in a system of artisanal production. Notable names of the era include among others the Italo-Jewish Modiano family and the Allatini. Benrubis founded also in 1880 one of the first retail companies in the Balkans.

After the Balkan Wars, Thessaloniki was incorporated into the Kingdom of Greece in 1913. At first the community feared that the annexation would lead to difficulties and during the first years its political stance was, in general, anti-Venizelist and pro-royalist/conservative. The Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917 during World War I burned much of the centre of the city and left 50,000 Jews homeless of the total of 72,000 residents who were burned out.[140] Having lost homes and their businesses, many Jews emigrated: to the United States, Palestine, and Paris. They could not wait for the government to create a new urban plan for rebuilding, which was eventually done.[232]

After the Greco-Turkish War in 1922 and the bilateral population exchange between Greece and Turkey, many refugees came to Greece. Nearly 100,000 ethnic Greeks resettled in Thessaloniki, reducing the proportion of Jews in the total community. After this, Jews made up about 20% of the city’s population. During the interwar period, Greece granted Jewish citizens the same civil rights as other Greek citizens.[140] In March 1926, Greece re-emphasized that all citizens of Greece enjoyed equal rights, and a considerable proportion of the city’s Jews decided to stay. During the Metaxas regime, the stance towards Jews became even better.

World War II brought a disaster for the Jewish Greeks, since in 1941 the Germans occupied Greece and began actions against the Jewish population. Greeks of the Resistance helped save some of the Jewish residents.[149] By the 1940s, the great majority of the Jewish Greek community firmly identified as both Greek and Jewish. According to Misha Glenny, such Greek Jews had largely not encountered «anti-Semitism as in its North European form.»[233]

In 1943, the Nazis began brutal actions against the historic Jewish population in Thessaloniki, forcing them into a ghetto near the railroad lines and beginning deportation to concentration and labor camps. They deported and exterminated approximately 96% of Thessaloniki’s Jews of all ages during the Holocaust.[234] The Thessaloniki Holocaust memorial in Eleftherias («Freedom») Square was built in 1997 in memory of all the Jewish people from Thessaloniki murdered in the Holocaust. The site was chosen because it was the place where Jewish residents were rounded up before embarking to trains for concentration camps.[235][236] Today, a community of around 1200 remains in the city.[149] Communities of descendants of Thessaloniki Jews – both Sephardic and Romaniote – live in other areas, mainly the United States and Israel.[234] Israeli singer Yehuda Poliker recorded a song about the Jewish people of Thessaloniki, called «Wait for me, Thessaloniki».

| Year | Total population |

Jewish population |

Jewish percentage |

Source[140] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1842 | 70,000 | 36,000 | 51% | Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer |

| 1870 | 90,000 | 50,000 | 56% | Greek schoolbook (G.K. Moraitopoulos, 1882) |

| 1882/84 | 85,000 | 48,000 | 56% | Ottoman government census |

| 1902 | 126,000 | 62,000 | 49% | Ottoman government census |

| 1913 | 157,889 | 61,439 | 39% | Greek government census |

| 1917 | 271,157 | 52,000 | 19% | [237] |

| 1943 | 50,000 | |||

| 2000 | 363,987[227] | 1,000 | 0.27% |

Others[edit]

Since the late 19th century, many merchants from Western Europe (mainly from France and Italy) were established in the city. They had an important role in the social and economic life of the city and introduced new industrial techniques. Their main district was what is known today as the «Frankish district» (near Ladadika), where the Catholic church designed by Vitaliano Poselli is also situated.[238][239] A part of them left after the incorporation of the city into the Greek kingdom, while others, who were of Jewish faith, were exterminated by the Nazis.

The Albanian community of the city has always been great and important. Albanians belong to two religions and they are Muslims and Christians. This has been the reason that they have never been numbered as a separate community, but sometimes they were numbered as Muslims and sometimes as Christians, then sometimes as Turkish and sometimes as Greek. It is thought that until 1922 the Albanian community was the largest in the city, after the Jewish community. The old Albanian cemeteries of the city are located in what is now called Triandria (they were destroyed in 1983).

The Bulgarian community of the city increased during the late 19th century.[240] The community had a Men’s High School, a Girl’s High School, a trade union and a gymnastics society. A large part of them were Catholics, as a result of actions by the Lazarists society, which had its base in the city.

Another group is the Armenian community which dates back to the Byzantine and Ottoman periods. During the 20th century, after the Armenian genocide and the defeat of the Greek army in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22), many fled to Greece including Thessaloniki. There is also an Armenian cemetery and an Armenian church at the centre of the city.[241]

Culture[edit]

Leisure and entertainment[edit]

Thessaloniki is regarded not only as the cultural and entertainment capital of northern Greece[198][242] but also the cultural capital of the country as a whole.[12] The city’s main theaters, run by the National Theatre of Northern Greece (Greek: Κρατικό Θέατρο Βορείου Ελλάδος) which was established in 1961,[243] include the Theater of the Society of Macedonian Studies, where the National Theater is based, the Royal Theater (Βασιλικό Θέατρο)-the first base of the National Theater-, Moni Lazariston, and the Earth Theater and Forest Theater, both amphitheatrical open-air theatres overlooking the city.[243]

The title of the European Capital of Culture in 1997 saw the birth of the city’s first opera[244] and today forms an independent section of the National Theatre of Northern Greece.[245] The opera is based at the Thessaloniki Concert Hall, one of the largest concert halls in Greece. Recently a second building was also constructed and designed by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki. Thessaloniki is also the seat of two symphony orchestras, the Thessaloniki State Symphony Orchestra and the Symphony Orchestra of the Municipality of Thessaloniki.

Olympion Theater, the site of the Thessaloniki International Film Festival and the Plateia Assos Odeon multiplex are the two major cinemas in downtown Thessaloniki. The city also has a number of multiplex cinemas in major shopping malls in the suburbs, most notably in Mediterranean Cosmos, the largest retail and entertainment development in the Balkans.

Thessaloniki is renowned for its major shopping streets and lively laneways. Tsimiski Street, Mitropoleos and Proxenou Koromila avenue are the city’s most famous shopping streets and are among Greece’s most expensive and exclusive high streets. The city is also home to one of Greece’s most famous and prestigious hotels, Makedonia Palace hotel, the Hyatt Regency Casino and hotel (the biggest casino in Greece and one of the biggest in Europe) and Waterland, the largest water park in southeastern Europe.

The city has long been known in Greece for its vibrant city culture, including having the most cafes and bars per capita of any city in Europe; and as having some of the best nightlife and entertainment in the country, thanks to its large young population and multicultural feel. Lonely Planet listed Thessaloniki among the world’s «ultimate party cities».[246]

Parks and recreation[edit]

Part of the coastline of the southeastern suburb of Peraia on the Thermaic Gulf, with views towards Thessaloniki

Although Thessaloniki is not renowned for its parks and greenery throughout its urban area, where green spaces are few, it has several large open spaces around its waterfront, namely the central city gardens of Palios Zoologikos Kipos (which is recently being redeveloped to also include rock climbing facilities, a new skatepark and paintball range),[247] the park of Pedion tou Areos, which also holds the city’s annual floral expo; and the parks of the Nea Paralia (waterfront) that span for 3 km (2 mi) along the coast, from the White Tower to the concert hall.

The Nea Paralia parks are used throughout the year for a variety of events, while they open up to the Thessaloniki waterfront, which is lined up with several cafés and bars; and during summer is full of Thessalonians enjoying their long evening walks (referred to as «the volta» and is embedded into the culture of the city). Having undergone an extensive revitalization, the city’s waterfront today features a total of 12 thematic gardens/parks.[248]

Thessaloniki’s proximity to places such as the national parks of Pieria and beaches of Chalkidiki often allow its residents to easily have access to some of the best outdoor recreation in Europe; however, the city is also right next to the Seich Sou forest national park, just 3.5 km (2 mi) away from Thessaloniki’s city centre; and offers residents and visitors alike, quiet viewpoints towards the city, mountain bike trails and landscaped hiking paths.[249] The city’s zoo, which is operated by the municipality of Thessaloniki, is also located nearby the national park.[250]

Other recreation spaces throughout the Thessaloniki metropolitan area include the Fragma Thermis, a landscaped parkland near Thermi and the Delta wetlands west of the city centre; while urban beaches that have continuously been awarded the blue flags,[251] are located along the 10 km (6 mi) coastline of Thessaloniki’s southeastern suburbs of Thermaikos, about 20 km (12 mi) away from the city centre.

Museums and galleries[edit]

Because of the city’s rich and diverse history, Thessaloniki houses many museums dealing with many different eras in history. Two of the city’s most famous museums include the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki and the Museum of Byzantine Culture.

The Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki was established in 1962 and houses some of the most important ancient Macedonian artifacts,[252] including an extensive collection of golden artwork from the royal palaces of Aigai and Pella.[253] It also houses exhibits from Macedon’s prehistoric past, dating from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age.[254] The Prehistoric Antiquities Museum of Thessaloniki has exhibits from those periods as well.

The Museum of Byzantine Culture is one of the city’s most famous museums, showcasing the city’s glorious Byzantine past.[255] The museum was also awarded Council of Europe’s museum prize in 2005.[256] The museum of the White Tower of Thessaloniki houses a series of galleries relating to the city’s past, from the creation of the White Tower until recent years.[257]

One of the most modern museums in the city is the Thessaloniki Science Centre and Technology Museum and is one of the most high-tech museums in Greece and southeastern Europe.[258] It features the largest planetarium in Greece, a cosmotheatre with the country’s largest flat screen, an amphitheater, a motion simulator with 3D projection and 6-axis movement and exhibition spaces.[258] Other industrial and technological museums in the city include the Railway Museum of Thessaloniki, which houses an original Orient Express train, the War Museum of Thessaloniki and others. The city also has a number of educational and sports museums, including the Thessaloniki History Centre and the Thessaloniki Olympic Museum.

The Atatürk Museum in Thessaloniki is the historic house where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of modern-day Turkey, was born. The house is now part of the Turkish consulate complex, but admission to the museum is free.[259] The museum contains historic information about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his life, especially while he was in Thessaloniki.[259]

Other ethnological museums of the sort include the Historical Museum of the Balkan Wars, the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki and the Museum of the Macedonian Struggle, containing information about the freedom fighters in Macedonia and their struggle to liberate the region from the Ottoman yoke.[260] Construction on the Holocaust Museum of Greece began in the city in 2018.[188]