Хараки́ри (яп. 腹切り?) или сэппуку (яп. 切腹?)[1] (букв. «вспарывание живота») — ритуальное самоубийство путём вспарывания живота, принятое среди самурайского сословия средневековой Японии.

Принятая в среде самураев, эта форма самоубийства совершалась либо по приговору как наказание, либо добровольно (в тех случаях, когда была затронута честь воина, в знак верности своему сёгуну и т. д.). Совершая сэппуку, самураи демонстрировали своё мужество перед лицом боли и смерти и чистоту своих помыслов перед богами и людьми. В случае, когда сэппуку должны были совершить лица, которым не доверяли, или которые были слишком опасны, или не хотели совершать самоубийство, ритуальный кинжал (кусунгобу) заменялся на веер, и таким образом сэппуку сводилась к обезглавливанию.

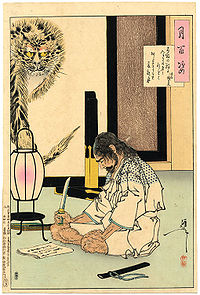

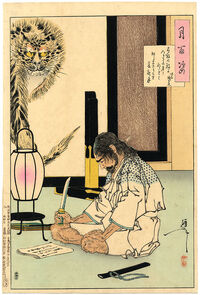

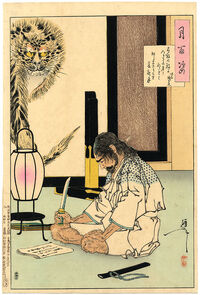

Генерал Акаси Гидаю готовится совершить сэппуку после проигранной битвы за своего господина Акэти Мицухидэ в 1582 году. Он только что написал свой предсмертный стих, который также можно видеть в верхнем правом углу картины.

Содержание

- 1 Этимология

- 2 История возникновения

- 3 Идеология

- 4 Примечания

- 5 Ссылки

Этимология

«Сэппуку» и «харакири» пишутся одними и теми же двумя иероглифами. Разница в том, что сэппуку пишется как 切腹 (сначала идёт иероглиф «резать» а потом «живот», при прочтении используются «онные», японско-китайские чтения), а харакири наоборот — 腹切り (первый иероглиф — «живот», используются «кунные», чисто японские чтения). В Японии слово «харакири» является разговорной формой и несёт некоторый бытовой и уничижительный оттенок: если «сэппуку» подразумевает совершённое по всем правилам ритуальное самоубийство, то «харакири» переводится скорее как «вспороть себе живот мечом».

История возникновения

В древности сэппуку не было распространено в Японии; чаще встречались другие способы самоубийства — самосожжение и повешение. Первое сепукку было совершено даймё из рода Минамото в войне между Минамото и Тайра , в 1156 году, при Хеген. Минамото но-Таметомо, побежденный в этой короткой, но жестокой войне, разрезал себе живот, чтобы избежать позора плена. Сэппуку быстро прививается среди военного сословия и становится почётным для самурая способом свести счёты с жизнью.

Сэппуку состояло в том, что самоубийца прорезал живот поперёк, от левого бока до правого или, по другому способу, прорезал его дважды: сначала горизонтально от левого бока к правому, а потом вертикально от диафрагмы до пупка. Впоследствии, когда сэппуку распространилось и стало применяться в качестве привилегированной смертной казни, для него был выработан особый сложный ритуал, один из важных моментов которого состоял в том, что помощник (кайсяку) невольного самоубийцы, обыкновенно его лучший друг, одним взмахом меча отрубал ему в нужный момент голову, так что сэппуку по сути сводилось к ритуальному обезглавливанию.

Между обезглавливанием по сэппуку и обыкновенным обезглавливанием установилась юридическая разница, и для привилегированных лиц, начиная с самураев, смертная казнь заменялась в виде снисхождения смертью через сэппуку, то есть смертной же казнью, но только в виде ритуального обезглавливания. Такая смертная казнь полагалась за проступки, не позорящие самурайской этики, поэтому она не считалась позорной, и в этом было её отличие от обыкновенной смертной казни. Такова была её идеология, но в какой мере она осуществлялась на практике, сказать трудно. Фактом остаётся только то, что сэппуку в виде казни применялось лишь к привилегированному сословию самураев и т. д., но никоим образом не к классам населения, считавшимся ниже самураев.

Это официальное применение сэппуку относится к более позднему времени, а именно к токугавскому периоду сёгуната, но независимо от него этот способ самоубийства в частном его применении получил очень широкое распространение во всей массе населения, почти став манией, и поводами для сэппуку стали служить самые ничтожные причины. После реставрации 1868 г. с началом организации государственного строя по европейскому образцу и начавшимся под давлением новых идей изменением всего вообще уклада жизни, официальное применение сэппуку в конце концов было отменено, а вместе с тем и частное его применение стало выводиться, но не вывелось совсем. Случаи сэппуку нередко встречались и в XX веке, и каждый такой случай встречался скрытым одобрением нации, создавая по отношению к некоторым применившим сэппуку лицам более видного положения ореол славы и величия.

Идеология

Существует точка зрения, согласно которой сэппуку усиленно насаждалось религиозными догматами буддизма, его концепцией бренности бытия и непостоянством всего земного.[2] В философии дзен-буддизма центром жизнедеятельности человека и местоположением его души считалось не сердце или голова, а живот[3], занимающий как бы срединное положение по отношению ко всему телу и способствующий более уравновешенному и гармоничному развитию человека. В связи с этим возникла масса выражений, описывающих разные душевные состояния человека с использованием слова «живот», по-японски хара [фуку]; например, харадацу — «ходить с поднявшимся животом» — «сердиться», хара китанай — «грязный живот» — «низкие стремления», хара-но курой хито — «человек с черным животом» — «человек с черной душой», хара-но най хито — «человек без живота» — «бездуховный человек». Считается, что вскрытие живота путём сэппуку осуществляется в целях показать чистоту и незапятнанность своих помыслов и устремлений, открытие своих сокровенных и истинных намерений, как доказательство своей внутренней правоты; другими словами, сэппуку является последним, крайним оправданием себя перед небом и людьми.

Также возможно, что возникновение этого обычая вызвано причинами более утилитарного характера, а именно постоянным наличием при себе орудия самоубийства — меча. Вспарывание живота мечом являлось очень действенным средством, и остаться в живых после такой раны было невозможно. В Европе существовала некоторая аналогия этого ритуала: обычай бросаться на меч в древнем Риме возник не в силу какой-нибудь особой идеологии этого явления, а в силу того, что меч был всегда при себе. Как на Западе, так и на Востоке применение меча как орудия для самоубийства началось именно среди сословия воинов, которые постоянно носили его при себе.

Примечания

Следует отметить, что проникающие ранения брюшной полости — самые болезненные по сравнению с подобными же ранениями других частей тела.

Распространено бытовое выражение «болевой шок», «смерть от болевого шока». Однако в действительности никакого «болевого шока» не существует, и умереть от одной лишь боли — даже очень сильной — человек не может.

- ↑ Возможные варианты траслитерации: сэппуку (по системе Поливанова), обряд сеппуку, сеппуко (ЭСБЕ).

- ↑ Искендеров А. А. Тоётоми Хидэёси. Главная редакция восточной литературы издательства «Наука», 1984.

- ↑ История стран Азии и Африки в средние века. – М.: Изд-во Московского университета, 1987.

Ссылки

- Jack Seward, Hara-Kiri: Japanese Ritual Suicide (Charles E. Tuttle, 1968)

- Christopher Ross, Mishima’s Sword: Travels in Search of a Samurai Legend (Fourth Estate, 2006; Da Capo Press 2006)

- Seppuku — A Practical Guide (tongue-in-cheek)

- An Account of the Hara-Kiri from Mitford’s «Tales of Old Japan» provides a detailed description: http://www.blackmask.com/thatway/books162c/taja.htm

- The Fine Art of Seppuku

- Zuihoden — Мавзолей Дате Масамунэ — Когда он умер, двадцать его сторонников убили себя, чтобы служить ему в следующей жизни

- Seppuku and «cruel punishments» at the end of Tokugawa Shogunate [1]

- Tokugawa Shogunate edict banning Junshi (Following one’s lord in death)

- SengokuDaimyo.com The website of Samurai Author and Historian Anthony J. Bryant

Wikimedia Foundation.

2010.

Seppuku with ritual attire and second (staged)

General Akashi Gidayu preparing to commit Seppuku after losing a battle for his master in 1582. He had just written his death poem, which is also visible in the upper right corner.

Seppuku (Japanese: 切腹, «stomach-cutting» or «belly slicing») is a form of Japanese ritual suicide by disembowelment. Seppuku is also known in English as hara-kiri (腹切り) and is written with the same kanji as seppuku but in reverse order with an okurigana. In Japanese, ‘hara-kiri’ is not in common usage, the term being regarded as gross and vulgar. The practice of committing seppuku at the death of one’s master is known as oibara (追腹 or 追い腹) or junshi (殉死); the ritual is similar.

Overview

Seppuku was a key part of bushido, the code of the samurai warriors; it was used by warriors to avoid falling into enemy hands, and to attenuate shame. Samurai could also be ordered by their daimyo (feudal lords) to commit seppuku. Later disgraced warriors were sometimes allowed to commit seppuku rather than be executed in the normal manner. Since the main point of the act was to restore or protect one’s honor as a warrior, those who did not belong to the samurai caste were never ordered or expected to commit seppuku. Samurai women could only commit the act with permission.

In his book The Samurai Way of Death, Samurai: The World of the Warrior (ch.4), Dr. Stephen Turnbull states:

Seppuku was commonly performed using a tantō. It could take place with preparation and ritual in the privacy of one’s home, or speedily in a quiet corner of a battlefield while one’s comrades kept the enemy at bay.

In the world of the warrior, seppuku was a deed of bravery that was admirable in a samurai who knew he was defeated, disgraced, or mortally wounded. It meant that he could end his days with his transgressions wiped away and with his reputation not merely intact but actually enhanced. The cutting of the abdomen released the samurai’s spirit in the most dramatic fashion, but it was an extremely painful and unpleasant way to die, and sometimes the samurai who was performing the act asked a loyal comrade to cut off his head at the moment of agony.

Sometimes a daimyo was called upon to perform seppuku as the basis of a peace agreement. This would weaken the defeated clan so that resistance would effectively cease. Toyotomi Hideyoshi used an enemy’s suicide in this way on several occasions, the most dramatic of which effectively ended a dynasty of daimyo forever, when the Hojo were defeated at Odawara in 1590. Hideyoshi insisted on the suicide of the retired daimyo Hojo Ujimasa, and the exile of his son Ujinao. With one sweep of a sword the most powerful daimyo family in eastern Japan disappeared from history.

Ritual

A tantō prepared for seppuku Women have their own ritual suicide, jigai. Here, the wife of Onodera Junai, one of the Forty-seven Ronin, prepares for her suicide; note the legs tied together, a female feature of seppuku to ensure a «decent» posture in death

In time, committing seppuku came to involve a detailed ritual. A Samurai was bathed, dressed in white robes, fed his favorite meal, and when he was finished, a Tanto or Wakazashi was placed on his plate. Dressed ceremonially, with his sword placed in front of him and sometimes seated on special cloths, the warrior would prepare for death by writing a death poem. With his selected attendant (kaishakunin, his second) standing by, he would open his kimono (clothing), take up his wakizashi (short sword) or a tantō (knife) and plunge it into his abdomen, making first a left-to-right cut and then a second slightly upward stroke to spill out the intestines. On the second stroke, the kaishakunin would perform daki-kubi, a cut in which the warrior is all but decapitated (a slight band of flesh is left attaching the head to the body). Because of the precision necessary for such a maneuver, the second was often a skilled swordsman. The principal agrees in advance when the kaishaku makes his cut, usually as soon as the dagger is plunged into the abdomen.

This elaborate ritual evolved after seppuku had ceased being mainly a battlefield or wartime practice and become a para judicial institution (see next section).

The second was usually, but not always, a friend. If a defeated warrior had fought honorably and well, an opponent who wanted to salute his bravery would volunteer to act as his second.

In the Hagakure, Yamamoto Tsunetomo wrote:

From ages past it has been considered ill-omened by samurai to be requested as kaishaku. The reason for this is that one gains no fame even if the job is well done. And if by chance one should blunder, it becomes a lifetime disgrace.

In the practice of past times, there were instances when the head flew off. It was said that it was best to cut leaving a little skin remaining so that it did not fly off in the direction of the verifying officials. However, at present it is best to cut clean through.

Some samurai chose to perform a considerably more taxing form of seppuku known as jūmonji-giri (十文字切り, lit. «cross-shaped cut»), in which there is no kaishakunin to put a quick end to the samurai’s suffering. It involves a second and more painful vertical cut across the belly. A samurai performing jumonji-giri was expected to bear his suffering quietly until perishing from loss of blood.

Seppuku as capital punishment

While the voluntary seppuku described above is the best known form and has been widely admired and idealized, in practice the most common form of seppuku was obligatory seppuku, used as a form of capital punishment for disgraced samurai, especially for those who committed a serious offense such as unprovoked murder, robbery, corruption, or treason. The samurai were generally told of their offense in full and given a set time to committ seppuku, usually before sunset on a given day. If the sentenced was uncooperative, it was not unheard of for them to be restrained, or for the actual execution to be carried out by decapitation while retaining only the trappings of seppuku; even the short sword laid out in front of the victim could be replaced with a fan. Unlike voluntary seppuku, seppuku carried out as capital punishment did not necessarily absolve the victim’s family of the crime. Depending on the severity of the crime, half or all of the deceased’s property could be confiscated, and the family stripped of rank.

The Western experience

The first recorded time a Westerner saw formal seppuku was the «Sakai Incident» of 1868. On February 15, twenty French sailors of the Dupleix entered a Japanese town called Sakai without official permission. Their presence caused panic among the residents. Security forces were dispatched to turn the sailors back to their ship, but a fight broke out and 11 sailors were shot dead. Upon the protest of the French representative, compensation of 15,000 yen was paid and those responsible were sentenced to death. The French captain was present to observe the execution. As each samurai committed ritual disembowelment, the gruesome nature of the act shocked the captain, and he requested a pardon, due to which nine of the samurai were spared. This incident was dramatized in a famous short story, Sakai Jiken, by Mori Ogai.

In the 1860s, The British Ambassador to Japan, Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale) lived within eyesight of Sengaku-ji where the Forty-seven Ronin are buried. In his book Tales of Old Japan, he describes a man who had come to the graves to kill himself:

I will add one anecdote to show the sanctity which is attached to the graves of the Forty-seven. In the month of September 1868, a certain man came to pray before the grave of Oishi Chikara. Having finished his prayers, he deliberately performed hara-kiri, and, the belly wound not being mortal, dispatched himself by cutting his throat. Upon his person were found papers setting forth that, being a Ronin and without means of earning a living, he had petitioned to be allowed to enter the clan of the Prince of Choshiu, which he looked upon as the noblest clan in the realm; his petition having been refused, nothing remained for him but to die, for to be a Ronin was hateful to him, and he would serve no other master than the Prince of Choshiu: what more fitting place could he find in which to put an end to his life than the graveyard of these Braves? This happened at about two hundred yards’ distance from my house, and when I saw the spot an hour or two later, the ground was all bespattered with blood, and disturbed by the death-struggles of the man.

Mitford also describes his friend’s eyewitness account of a Seppuku:

There are many stories on record of extraordinary heroism being displayed in the hara-kiri. The case of a young fellow, only twenty years old, of the Choshiu clan, which was told me the other day by an eye-witness, deserves mention as a marvellous instance of determination. Not content with giving himself the one necessary cut, he slashed himself thrice horizontally and twice vertically. Then he stabbed himself in the throat until the dirk protruded on the other side, with its sharp edge to the front; setting his teeth in one supreme effort, he drove the knife forward with both hands through his throat, and fell dead.

During the Meiji Restoration, the Tokugawa Shogun’s aide committed Seppuku:

One more story and I have done. During the revolution, when the Taikun (Supreme Commander), beaten on every side, fled ignominiously to Yedo, he is said to have determined to fight no more, but to yield everything. A member of his second council went to him and said, “Sir, the only way for you now to retrieve the honour of the family of Tokugawa is to disembowel yourself; and to prove to you that I am sincere and disinterested in what I say, I am here ready to disembowel myself with you.” The Taikun flew into a great rage, saying that he would listen to no such nonsense, and left the room. His faithful retainer, to prove his honesty, retired to another part of the castle, and solemnly performed the hara-kiri.

In his book Tales of Old Japan, Mitford describes witnessing a hara-kiri [1]:

As a corollary to the above elaborate statement of the ceremonies proper to be observed at the hara-kiri, I may here describe an instance of such an execution which I was sent officially to witness. The condemned man was Taki Zenzaburo, an officer of the Prince of Bizen, who gave the order to fire upon the foreign settlement at Hiogo in the month of February 1868,—an attack to which I have alluded in the preamble to the story of the Eta Maiden and the Hatamoto. Up to that time no foreigner had witnessed such an execution, which was rather looked upon as a traveller’s fable.

The ceremony, which was ordered by the Mikado himself, took place at 10:30 at night in the temple of Seifukuji, the headquarters of the Satsuma troops at Hiogo. A witness was sent from each of the foreign legations. We were seven foreigners in all.

«After another profound obeisance, Taki Zenzaburo, in a voice which betrayed just so much emotion and hesitation as might be expected from a man who is making a painful confession, but with no sign of either in his face or manner, spoke as follows:

«I, and I alone, unwarrantably gave the order to fire on the foreigners at Kobe, and again as they tried to escape. For this crime I disembowel myself, and I beg you who are present to do me the honour of witnessing the act.»

Bowing once more, the speaker allowed his upper garments to slip down to his girdle, and remained naked to the waist. Carefully, according to custom, he tucked his sleeves under his knees to prevent himself from falling backwards; for a noble Japanese gentleman should die falling forwards. Deliberately, with a steady hand, he took the dirk that lay before him; he looked at it wistfully, almost affectionately; for a moment he seemed to collect his thoughts for the last time, and then stabbing himself deeply below the waist on the left-hand side, he drew the dirk slowly across to the right side, and, turning it in the wound, gave a slight cut upwards. During this sickeningly painful operation he never moved a muscle of his face. When he drew out the dirk, he leaned forward and stretched out his neck; an expression of pain for the first time crossed his face, but he uttered no sound. At that moment the kaishaku, who, still crouching by his side, had been keenly watching his every movement, sprang to his feet, poised his sword for a second in the air; there was a flash, a heavy, ugly thud, a crashing fall; with one blow the head had been severed from the body.

A dead silence followed, broken only by the hideous noise of the blood throbbing out of the inert heap before us, which but a moment before had been a brave and chivalrous man. It was horrible.

The kaishaku made a low bow, wiped his sword with a piece of rice paper which he had ready for the purpose, and retired from the raised floor; and the stained dirk was solemnly borne away, a bloody proof of the execution.

The two representatives of the Mikado then left their places, and, crossing over to where the foreign witnesses sat, called us to witness that the sentence of death upon Taki Zenzaburo had been faithfully carried out. The ceremony being at an end, we left the temple.

The ceremony, to which the place and the hour gave an additional solemnity, was characterised throughout by that extreme dignity and punctiliousness which are the distinctive marks of the proceedings of Japanese gentlemen of rank; and it is important to note this fact, because it carries with it the conviction that the dead man was indeed the officer who had committed the crime, and no substitute. While profoundly impressed by the terrible scene it was impossible at the same time not to be filled with admiration of the firm and manly bearing of the sufferer, and of the nerve with which the kaishaku performed his last duty to his master.»

Seppuku in modern Japan

Seppuku as judicial punishment was officially abolished in 1873, shortly after the Meiji Restoration, but voluntary seppuku did not completely die out. Dozens of people are known to have committed seppuku since then, including some military men who committed suicide in 1895 as a protest against the return of a conquered territory to China[citation needed]; by General Nogi and his wife on the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912; and by numerous soldiers and civilians who chose to die rather than surrender at the end of World War II.

In 1970, famed author Yukio Mishima and one of his followers committed public seppuku at the Japan Self-Defense Forces headquarters after an unsuccessful attempt to incite the armed forces to stage a coup d’état. Mishima committed seppuku in the office of General Kanetoshi Mashita. His second, a 25-year-old named Masakatsu Morita, tried three times to ritually behead Mishima but failed; his head was finally severed by Hiroyasu Koga. Morita then attempted to commit seppuku himself. Although his own cuts were too shallow to be fatal, he gave the signal and he too was beheaded by Koga.

In 1999, Masaharu Nonaka, a 58-year-old employee of Bridgestone in Japan, slashed his belly with a sashimi knife to protest his forced retirement. He died later in the hospital. This suicide was said to represent the difficulties in Japan following the collapse of the bubble economy.

Well-known people who committed seppuku

- Yukio Mishima

- Sen no Rikyu

- Anami Korechika

- Maresuke Nogi

- Karl Haushofer

- Minamoto Yoshitsune

In pop culture

Template:Spoilers

In the South Park episode «Stupid Spoiled Whore Video Playset«, Cuddles, one of Paris Hilton‘s many suicidal pets, is shown to have performed seppuku.

In the Drawn Together episode «Captain Girl«, after losing a game of «Not-it!» to determine who has to be the one to impregnate Toot, Ling-Ling commits seppuku.

In the recently aired «lost episodes» of Chappelle’s Show, Dave Chappelle investigates «racist pixies» that urge moderate individuals of all races to give in to their stereotypical behavior, such as blacks eating chicken, Mexicans modifying their cars with Jesus Christ memorabilia, Japanese being unable to speak the letter L, whites being uptight and hypocritical, and so forth. All pixies are played by Chappelle in their respective «uniforms» or appearances. When a Japanese man does not give into his stereotypical tendency, the pixie commits seppuku.

Seppuku features prominently in Western depictions of pre-Meiji Japan in books, movies, videogames, etc. such as The Last Samurai or the novel Shogun. Some video games give players the option of committing seppuku: Mortal Kombat: Deception adds a new «Fatality» feature to the series called «Hara-kiri,» which allows a defeated player to kill himself in a graphic manner before his opponent can (although none of them are literally under the proper seppuku method, except Kenshi who comes close). It could reappear in the upcoming game Mortal Kombat: Armageddon.

In American media, particular television and film from the 1940s-1960s era, the term «hara-kiri» was often mispronounced and misromanized as «Harry Carry». (See, for example, the TV series McHale’s Navy). In the 1980s, it was morphed to «Harry Caray», due to the popularity of the eponymous baseball announcer.

In the World War II era propaganda film Across the Pacific, Japanese agent Dr. Lorenz, played by Sydney Greenstreet, attempts to commit seppuku when his plot to sabotage the Panama Canal is foiled by Humphrey Bogart‘s Rick Leland. His nerve fails, and he is captured instead.

In the manga/anime Ranma ½, Genma promised his wife Nodoka that he would raise his son Ranma to be a man among men. If he failed, both he and Ranma would commit seppuku. Ranma falls into a cursed spring that causes him to turn into a girl when splashed with cold water, and Genma (who changes into a panda with cold water) hides Ranma and himself whenever Nodoka comes around. Ranma often called him/herself Ranko to spend time with his mother, although she doesn’t find out until late in the manga. Eventually Nodoka finds out and declares Ranma to be a man despite the curse, so no one had to commit seppuku.

Raymond Feist‘s fictional realm of Tsuranuanni is based on the real-world Japan and also has the concept of seppuku, but not by that name.

For the most part, seppuku is depicted in popular culture as marking a true warrior’s ethos and the (stereotypical) mystical Eastern understanding of death. The dutiful suicide of seppuku is often seen as a uniquely Japanese cultural trait, although the Western tradition has its share of historical figures who have killed themselves when facing dishonor, death or both at the hands of their enemies.

In Raymond Benson‘s James Bond book The Man with the Red Tattoo, the main villain, Yami Shogun Goro Yoshida commits seppuku just before Bond could capture him. Yasutake Tsukamoto, yakuza leader and Yoshida’s secundant, tells Bond that Yoshida won, because he «robbed Bond of the ultimate victory». Bond tells Tsukamoto that he does not care about it, because «he’s bloody dead and that’s all that matters.»

In Giacomo Puccini‘s opera, Madame Butterfly, the heroine Cio-cio-san, commits Seppuku at the end of the final act.

Unit leaders in computer strategy game Shogun: Total War may commit seppuku if the units they command are defeated in combat too many times.

In the computer game Samurai Warrior: The Battles of Usagi Yojimbo (Firebird Software, 1988), game character Usagi Yojimbo automatically commits seppuku when dishonorable actions performed by the player make karma counter reach zero.

In the computer game Warcraft III the night elf demon hunter, Illidan, commits ritual suicide as part of his death animation.

Microprose’s 1989 role-playing/strategy game Sword of the Samurai allowed a character to commit seppuku following any sudden loss of honor, usually after being captured or recognized whilst attempting murder or treachery against his lord or feudal rivals. At the initial samurai and hatamoto levels, this ‘option’ presents as a capital punishment handed down by the player’s lord; anything short of immediate compliance would see the character and his family (including any heirs) hunted down and executed. In the later stages of the game, daimyo-ranked characters so dishonored were given the option to commit seppuku but were under no compulsion to do so beyond the strategic disadvantages arising from dishonor.

In the fighting game series Tekken and Soul Calibur, the character Yoshimitsu has a move (the «Turning Suicide») wherin he turns away from the enemy and stabs his sword through his stomach and out his back. If the sword connects with Yoshimitsu’s opponent, it causes devastating damage to them, and minor damage to Yoshimitsu himself. However, if it misses, it drains half of Yoshimitsu’s life.

In the action/stealth video game Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory the antagonist, Admiral Toshiro Otomo, wishes for Japan to once again assume the mantle of imperialism and tries to lure the USA and the Koreas into war. When Otomo’s plan falls through, he commits seppuku in front of Sam Fisher rather than be brought to justice. In a ironic twist however, Otomo is saved by Fisher and he is brought to justice.

In the action/stealth videogame «Tenchu: Stealth Assassins«, Lord Gohda orders his ninja to execute a corrupt minister named Kataoka. If the player confronts him as Ayame, he refuses to be insulted by a woman and they fight to the death. But as Rikimaru, Kataoka respects Gohda’s request to be killed and commits seppuku, with Rikimaru acting as his second.

The cult website realultimatepower.net describes a darkly hilarious method of committing seppuku by swallowing a Frisbee.

Ninja Burger‘s website ninjaburger.com, a parody of fast food delivery services, states on their webpage: Guaranteed delivery in 30 minutes or less, or we commit Seppuku!

In the American film Harold and Maude, the character Harold, a young man obsessed with death, fakes his own suicide in a multitude of ways. At one point, he brings out a blade and educates a woman in the art of «hara-kiri» before going through with the (faked) ritual.

In the motion picture Airplane! a japanese man is literally ‘bored to death’ by Ted Stryker (Robert Hays) describing his war record, and commits seppuku by disemboweling himself with a sword while sitting in his airplane seat.

Seppuku is depicted twice on the American film The Last Samurai, at the beginning of the movie after the general of the Japanese newly formed army faces defeat in the hands of Katsumoto’s (played by Ken Watanabe) forces, and later, near the end of the film, with Katsumoto committing seppuku after his army is killed to the last man (all but Nathan Algren, played by Tom Cruise). In the first instance, we see Katsumoto in the role of kaishaku, beheading General Hasegawa to quickly end his suffering. This action comes as a shock to Algren, who sees it as a barbaric form of execution. Finally, defeated on the battlefield it is Algren who helps Katsumoto to end his life with honor by pushing the dagger all the way into his friend’s stomach.

Seppuku and other forms of suicide are looked upon with disfavor in the popular anime/manga series Rurouni Kenshin. Paricularly in the anime series, Kenshin often talks well meaning opponents or people in despair out of suicide, explaining that their deaths will not make up for the mistakes they have made, nor give them any honor. Instead, the best way to atone for ones past or to be truly honorable is to continue living and doing all the good one can in the world. This is Kenshin’s own form of penance for his bloody past as an assassin and the death of his first wife, and several of the characters he speaks to about it comment that living with and struggling to overcome such guilt and doubt is a harder fate than death.

In Internet culture, there is a type of ‘scavenger hunt’ game known as Google Seppuku, where participants type in a (usually Japanese) word or phrase into Google’s image search tool, and look for the most disturbing picture among them. The name derives from the fact that, like modern-day beliefs of committing seppuku, the participants are willfully submitting themselves to something inexplicably awful and painful for glory and honor (in this case, finding the most disturbing picture on the internet that no one can top).

In the Playstation videogame, Bushido Blade, the player can commit seppuku on their own character. It serves no actual function in the game other than adding authenticity.

In the old Commodore 64, Amstrad CPC and ZX Spectrum game, Samurai Warrior: The Battles of Usagi Yojimbo, Usagi would automatically commit seppuku if his karma drops to 0.

In The Ultimate Showdown of Ultimate Destiny, the winning character, Mr. Rogers, commits seppuku.

Seppuku is a common theme in the manga Gin Tama.

In the popular anime/manga One Piece, the CP9 member Kumadori often attempts to commit seppuku for his partners lack of respect or failure, but his superhuman strength prevents it from working.

Towards the end of Hideo Kojima’s MGS:2, a computer A.I. operating under the alias of Colonel Campbell gets infected by a virus and begins spewing nonsensical messages including, «I hear its amazing when the famous purple stuffed worm in flap-jaw space with the tuning fork does a raw blink on Hari Kiri Rock. I need scissors! 61!»

In the Futurama episode The 30% Iron Chef being dishonored (for framing Fry) Dr. Zoidberg grabs a host’s ceremonial Wakazashi, but when he trys to plunge the sword into himself and commit seppuku the blade bends and folds instead of cutting him open.

In the second episode of the Singapore dub of One Piece, Zoro says to Luffy that, if Luffy gets in the way of his dream to be the world’s greatest swordsman, Zoro will have to commit hari-kari, where as in the original japanese it is Luffy who has to commit hara-kiri if he gets in the way.

In Yakitate! Japan, the rather exaggerated samurai bread baker Suwabara Kai mentions seppuku a few times, once saying to his teammate Kawachi Kyosuke who has ruined a bread the team was going to enter in a contest that if he were a real Japanese man, he should take responsibility for his mistake by committing seppuku. Another time Suwabara says that if he loses his Yakitate 9 match against Azuma, he will commit seppuku. He is talked out of this in the end, of course.

In the film Scary Movie 4, the Japanese ambassador to the United Nations committed seppuku upon seeing the US President nude during the demonstration of the reverse-engineered alien heat ray weapon. In this case, it was more out of disgust rather than dishonor.

In the computer game series Wing Commander, the Kilrathi is known to commit ritual suicides akin to seppuku.

In Xenosaga Episode III, Margulis commits seppuku after losing his final battle against Jin.

In the 1998 film The Big Hit The bankrupted father of kidnapped victim Keiko Nishi tries repeatedly to commit seppuku but is interupted by the phone ringing.

In a more adult sketch from the black comedy series Hale & Pace commedian Hale commits seppuku infront of his comedy partner Pace having moments before inadvertedly sliced Pace horizontally in half. With this action being delayed for comic affect and not occuring to Pace until after Hale has died.

In The Adventures of Tintin story The Blue Lotus, Tintin catches sight of a headline in the local newspaper about one of the villans having commited suicide by «hara-kiri» after being exposed as a drug dealing terrorist.

In the video/arcade series Darkstalkers, the character Bishamon can execute a move that, if it connects, forces the opponent to commit seppuku.

See also

- Kamikaze

- Yukio Mishima

- Japanese funeral

- Nakano Seigo

- Jigai

Further reading

- Jack Seward, Hara-Kiri: Japanese Ritual Suicide (Charles E. Tuttle, 1968)

- Seppuku — A Practical Guide (tongue-in-cheek)

- An Account of the Hara-Kiri from Mitford’s «Tales of Old Japan» provides a detailed description: http://www.blackmask.com/thatway/books162c/taja.htm

- The samurai way of death —a chapter from «Samurai: The World of the Warrior» by Dr. Stephen Turnbull

- The Fine Art of Seppuku

- Zuihoden — The mausoleum of Date Masamune — When he died, twenty of his followers killed themselves to serve him in the next life. They lay in state at Zuihoden

- Seppuku and «cruel punishments» at the end of Tokugawa Shogunate [2]

- Tokugawa Shogunate edict banning Junshi (Following one’s lord in death) From the Buke Sho Hatto (1663 AD)—

- «That the custom of following a master in death is wrong and unprofitable is a caution which has been at times given of old; but, owing to the fact that it has not actually been prohibited, the number of those who cut their belly to follow their lord on his decease has become very great. For the future, to those retainers who may be animated by such an idea, their respective lords should intimate, constantly and in very strong terms, their disapproval of the custom. If, notwithstanding this warning, any instance of the practice should occur, it will be deemed that the deceased lord was to blame for unreadiness. Henceforward, moreover, his son and successor will be held to be blameworthy for incompetence, as not having prevented the suicides.»

- SengokuDaimyo.com The website of Samurai Author and Historian Anthony J. Bryant

bn:হারা-কিরি

bs:Seppuku

bg:Сепуку

cs:Seppuku

de:Seppuku

et:Harakiri

es:Seppuku

fr:Seppuku

hr:Seppuku

id:Seppuku

is:Seppuku

he:ספוקו

ka:სეპუკუ

lt:Sepuku

nl:Seppuku

pt:Seppuku

ro:Seppuku

ru:Сэппуку

sl:Seppuku

sr:Сепуку

fi:Seppuku

sv:Harakiri

th:ฮาราคีรี

zh:切腹

Seppuku with ritual attire and second (staged)

General Akashi Gidayu preparing to commit Seppuku after losing a battle for his master in 1582. He had just written his death poem, which is also visible in the upper right corner.

Seppuku (Japanese: 切腹, «stomach-cutting» or «belly slicing») is a form of Japanese ritual suicide by disembowelment. Seppuku is also known in English as hara-kiri (腹切り) and is written with the same kanji as seppuku but in reverse order with an okurigana. In Japanese, ‘hara-kiri’ is not in common usage, the term being regarded as gross and vulgar. The practice of committing seppuku at the death of one’s master is known as oibara (追腹 or 追い腹) or junshi (殉死); the ritual is similar.

Overview

Seppuku was a key part of bushido, the code of the samurai warriors; it was used by warriors to avoid falling into enemy hands, and to attenuate shame. Samurai could also be ordered by their daimyo (feudal lords) to commit seppuku. Later disgraced warriors were sometimes allowed to commit seppuku rather than be executed in the normal manner. Since the main point of the act was to restore or protect one’s honor as a warrior, those who did not belong to the samurai caste were never ordered or expected to commit seppuku. Samurai women could only commit the act with permission.

In his book The Samurai Way of Death, Samurai: The World of the Warrior (ch.4), Dr. Stephen Turnbull states:

Seppuku was commonly performed using a tantō. It could take place with preparation and ritual in the privacy of one’s home, or speedily in a quiet corner of a battlefield while one’s comrades kept the enemy at bay.

In the world of the warrior, seppuku was a deed of bravery that was admirable in a samurai who knew he was defeated, disgraced, or mortally wounded. It meant that he could end his days with his transgressions wiped away and with his reputation not merely intact but actually enhanced. The cutting of the abdomen released the samurai’s spirit in the most dramatic fashion, but it was an extremely painful and unpleasant way to die, and sometimes the samurai who was performing the act asked a loyal comrade to cut off his head at the moment of agony.

Sometimes a daimyo was called upon to perform seppuku as the basis of a peace agreement. This would weaken the defeated clan so that resistance would effectively cease. Toyotomi Hideyoshi used an enemy’s suicide in this way on several occasions, the most dramatic of which effectively ended a dynasty of daimyo forever, when the Hojo were defeated at Odawara in 1590. Hideyoshi insisted on the suicide of the retired daimyo Hojo Ujimasa, and the exile of his son Ujinao. With one sweep of a sword the most powerful daimyo family in eastern Japan disappeared from history.

Ritual

A tantō prepared for seppuku Women have their own ritual suicide, jigai. Here, the wife of Onodera Junai, one of the Forty-seven Ronin, prepares for her suicide; note the legs tied together, a female feature of seppuku to ensure a «decent» posture in death

In time, committing seppuku came to involve a detailed ritual. A Samurai was bathed, dressed in white robes, fed his favorite meal, and when he was finished, a Tanto or Wakazashi was placed on his plate. Dressed ceremonially, with his sword placed in front of him and sometimes seated on special cloths, the warrior would prepare for death by writing a death poem. With his selected attendant (kaishakunin, his second) standing by, he would open his kimono (clothing), take up his wakizashi (short sword) or a tantō (knife) and plunge it into his abdomen, making first a left-to-right cut and then a second slightly upward stroke to spill out the intestines. On the second stroke, the kaishakunin would perform daki-kubi, a cut in which the warrior is all but decapitated (a slight band of flesh is left attaching the head to the body). Because of the precision necessary for such a maneuver, the second was often a skilled swordsman. The principal agrees in advance when the kaishaku makes his cut, usually as soon as the dagger is plunged into the abdomen.

This elaborate ritual evolved after seppuku had ceased being mainly a battlefield or wartime practice and become a para judicial institution (see next section).

The second was usually, but not always, a friend. If a defeated warrior had fought honorably and well, an opponent who wanted to salute his bravery would volunteer to act as his second.

In the Hagakure, Yamamoto Tsunetomo wrote:

From ages past it has been considered ill-omened by samurai to be requested as kaishaku. The reason for this is that one gains no fame even if the job is well done. And if by chance one should blunder, it becomes a lifetime disgrace.

In the practice of past times, there were instances when the head flew off. It was said that it was best to cut leaving a little skin remaining so that it did not fly off in the direction of the verifying officials. However, at present it is best to cut clean through.

Some samurai chose to perform a considerably more taxing form of seppuku known as jūmonji-giri (十文字切り, lit. «cross-shaped cut»), in which there is no kaishakunin to put a quick end to the samurai’s suffering. It involves a second and more painful vertical cut across the belly. A samurai performing jumonji-giri was expected to bear his suffering quietly until perishing from loss of blood.

Seppuku as capital punishment

While the voluntary seppuku described above is the best known form and has been widely admired and idealized, in practice the most common form of seppuku was obligatory seppuku, used as a form of capital punishment for disgraced samurai, especially for those who committed a serious offense such as unprovoked murder, robbery, corruption, or treason. The samurai were generally told of their offense in full and given a set time to committ seppuku, usually before sunset on a given day. If the sentenced was uncooperative, it was not unheard of for them to be restrained, or for the actual execution to be carried out by decapitation while retaining only the trappings of seppuku; even the short sword laid out in front of the victim could be replaced with a fan. Unlike voluntary seppuku, seppuku carried out as capital punishment did not necessarily absolve the victim’s family of the crime. Depending on the severity of the crime, half or all of the deceased’s property could be confiscated, and the family stripped of rank.

The Western experience

The first recorded time a Westerner saw formal seppuku was the «Sakai Incident» of 1868. On February 15, twenty French sailors of the Dupleix entered a Japanese town called Sakai without official permission. Their presence caused panic among the residents. Security forces were dispatched to turn the sailors back to their ship, but a fight broke out and 11 sailors were shot dead. Upon the protest of the French representative, compensation of 15,000 yen was paid and those responsible were sentenced to death. The French captain was present to observe the execution. As each samurai committed ritual disembowelment, the gruesome nature of the act shocked the captain, and he requested a pardon, due to which nine of the samurai were spared. This incident was dramatized in a famous short story, Sakai Jiken, by Mori Ogai.

In the 1860s, The British Ambassador to Japan, Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford (Lord Redesdale) lived within eyesight of Sengaku-ji where the Forty-seven Ronin are buried. In his book Tales of Old Japan, he describes a man who had come to the graves to kill himself:

I will add one anecdote to show the sanctity which is attached to the graves of the Forty-seven. In the month of September 1868, a certain man came to pray before the grave of Oishi Chikara. Having finished his prayers, he deliberately performed hara-kiri, and, the belly wound not being mortal, dispatched himself by cutting his throat. Upon his person were found papers setting forth that, being a Ronin and without means of earning a living, he had petitioned to be allowed to enter the clan of the Prince of Choshiu, which he looked upon as the noblest clan in the realm; his petition having been refused, nothing remained for him but to die, for to be a Ronin was hateful to him, and he would serve no other master than the Prince of Choshiu: what more fitting place could he find in which to put an end to his life than the graveyard of these Braves? This happened at about two hundred yards’ distance from my house, and when I saw the spot an hour or two later, the ground was all bespattered with blood, and disturbed by the death-struggles of the man.

Mitford also describes his friend’s eyewitness account of a Seppuku:

There are many stories on record of extraordinary heroism being displayed in the hara-kiri. The case of a young fellow, only twenty years old, of the Choshiu clan, which was told me the other day by an eye-witness, deserves mention as a marvellous instance of determination. Not content with giving himself the one necessary cut, he slashed himself thrice horizontally and twice vertically. Then he stabbed himself in the throat until the dirk protruded on the other side, with its sharp edge to the front; setting his teeth in one supreme effort, he drove the knife forward with both hands through his throat, and fell dead.

During the Meiji Restoration, the Tokugawa Shogun’s aide committed Seppuku:

One more story and I have done. During the revolution, when the Taikun (Supreme Commander), beaten on every side, fled ignominiously to Yedo, he is said to have determined to fight no more, but to yield everything. A member of his second council went to him and said, “Sir, the only way for you now to retrieve the honour of the family of Tokugawa is to disembowel yourself; and to prove to you that I am sincere and disinterested in what I say, I am here ready to disembowel myself with you.” The Taikun flew into a great rage, saying that he would listen to no such nonsense, and left the room. His faithful retainer, to prove his honesty, retired to another part of the castle, and solemnly performed the hara-kiri.

In his book Tales of Old Japan, Mitford describes witnessing a hara-kiri [1]:

As a corollary to the above elaborate statement of the ceremonies proper to be observed at the hara-kiri, I may here describe an instance of such an execution which I was sent officially to witness. The condemned man was Taki Zenzaburo, an officer of the Prince of Bizen, who gave the order to fire upon the foreign settlement at Hiogo in the month of February 1868,—an attack to which I have alluded in the preamble to the story of the Eta Maiden and the Hatamoto. Up to that time no foreigner had witnessed such an execution, which was rather looked upon as a traveller’s fable.

The ceremony, which was ordered by the Mikado himself, took place at 10:30 at night in the temple of Seifukuji, the headquarters of the Satsuma troops at Hiogo. A witness was sent from each of the foreign legations. We were seven foreigners in all.

«After another profound obeisance, Taki Zenzaburo, in a voice which betrayed just so much emotion and hesitation as might be expected from a man who is making a painful confession, but with no sign of either in his face or manner, spoke as follows:

«I, and I alone, unwarrantably gave the order to fire on the foreigners at Kobe, and again as they tried to escape. For this crime I disembowel myself, and I beg you who are present to do me the honour of witnessing the act.»

Bowing once more, the speaker allowed his upper garments to slip down to his girdle, and remained naked to the waist. Carefully, according to custom, he tucked his sleeves under his knees to prevent himself from falling backwards; for a noble Japanese gentleman should die falling forwards. Deliberately, with a steady hand, he took the dirk that lay before him; he looked at it wistfully, almost affectionately; for a moment he seemed to collect his thoughts for the last time, and then stabbing himself deeply below the waist on the left-hand side, he drew the dirk slowly across to the right side, and, turning it in the wound, gave a slight cut upwards. During this sickeningly painful operation he never moved a muscle of his face. When he drew out the dirk, he leaned forward and stretched out his neck; an expression of pain for the first time crossed his face, but he uttered no sound. At that moment the kaishaku, who, still crouching by his side, had been keenly watching his every movement, sprang to his feet, poised his sword for a second in the air; there was a flash, a heavy, ugly thud, a crashing fall; with one blow the head had been severed from the body.

A dead silence followed, broken only by the hideous noise of the blood throbbing out of the inert heap before us, which but a moment before had been a brave and chivalrous man. It was horrible.

The kaishaku made a low bow, wiped his sword with a piece of rice paper which he had ready for the purpose, and retired from the raised floor; and the stained dirk was solemnly borne away, a bloody proof of the execution.

The two representatives of the Mikado then left their places, and, crossing over to where the foreign witnesses sat, called us to witness that the sentence of death upon Taki Zenzaburo had been faithfully carried out. The ceremony being at an end, we left the temple.

The ceremony, to which the place and the hour gave an additional solemnity, was characterised throughout by that extreme dignity and punctiliousness which are the distinctive marks of the proceedings of Japanese gentlemen of rank; and it is important to note this fact, because it carries with it the conviction that the dead man was indeed the officer who had committed the crime, and no substitute. While profoundly impressed by the terrible scene it was impossible at the same time not to be filled with admiration of the firm and manly bearing of the sufferer, and of the nerve with which the kaishaku performed his last duty to his master.»

Seppuku in modern Japan

Seppuku as judicial punishment was officially abolished in 1873, shortly after the Meiji Restoration, but voluntary seppuku did not completely die out. Dozens of people are known to have committed seppuku since then, including some military men who committed suicide in 1895 as a protest against the return of a conquered territory to China[citation needed]; by General Nogi and his wife on the death of Emperor Meiji in 1912; and by numerous soldiers and civilians who chose to die rather than surrender at the end of World War II.

In 1970, famed author Yukio Mishima and one of his followers committed public seppuku at the Japan Self-Defense Forces headquarters after an unsuccessful attempt to incite the armed forces to stage a coup d’état. Mishima committed seppuku in the office of General Kanetoshi Mashita. His second, a 25-year-old named Masakatsu Morita, tried three times to ritually behead Mishima but failed; his head was finally severed by Hiroyasu Koga. Morita then attempted to commit seppuku himself. Although his own cuts were too shallow to be fatal, he gave the signal and he too was beheaded by Koga.

In 1999, Masaharu Nonaka, a 58-year-old employee of Bridgestone in Japan, slashed his belly with a sashimi knife to protest his forced retirement. He died later in the hospital. This suicide was said to represent the difficulties in Japan following the collapse of the bubble economy.

Well-known people who committed seppuku

- Yukio Mishima

- Sen no Rikyu

- Anami Korechika

- Maresuke Nogi

- Karl Haushofer

- Minamoto Yoshitsune

In pop culture

Template:Spoilers

In the South Park episode «Stupid Spoiled Whore Video Playset«, Cuddles, one of Paris Hilton‘s many suicidal pets, is shown to have performed seppuku.

In the Drawn Together episode «Captain Girl«, after losing a game of «Not-it!» to determine who has to be the one to impregnate Toot, Ling-Ling commits seppuku.

In the recently aired «lost episodes» of Chappelle’s Show, Dave Chappelle investigates «racist pixies» that urge moderate individuals of all races to give in to their stereotypical behavior, such as blacks eating chicken, Mexicans modifying their cars with Jesus Christ memorabilia, Japanese being unable to speak the letter L, whites being uptight and hypocritical, and so forth. All pixies are played by Chappelle in their respective «uniforms» or appearances. When a Japanese man does not give into his stereotypical tendency, the pixie commits seppuku.

Seppuku features prominently in Western depictions of pre-Meiji Japan in books, movies, videogames, etc. such as The Last Samurai or the novel Shogun. Some video games give players the option of committing seppuku: Mortal Kombat: Deception adds a new «Fatality» feature to the series called «Hara-kiri,» which allows a defeated player to kill himself in a graphic manner before his opponent can (although none of them are literally under the proper seppuku method, except Kenshi who comes close). It could reappear in the upcoming game Mortal Kombat: Armageddon.

In American media, particular television and film from the 1940s-1960s era, the term «hara-kiri» was often mispronounced and misromanized as «Harry Carry». (See, for example, the TV series McHale’s Navy). In the 1980s, it was morphed to «Harry Caray», due to the popularity of the eponymous baseball announcer.

In the World War II era propaganda film Across the Pacific, Japanese agent Dr. Lorenz, played by Sydney Greenstreet, attempts to commit seppuku when his plot to sabotage the Panama Canal is foiled by Humphrey Bogart‘s Rick Leland. His nerve fails, and he is captured instead.

In the manga/anime Ranma ½, Genma promised his wife Nodoka that he would raise his son Ranma to be a man among men. If he failed, both he and Ranma would commit seppuku. Ranma falls into a cursed spring that causes him to turn into a girl when splashed with cold water, and Genma (who changes into a panda with cold water) hides Ranma and himself whenever Nodoka comes around. Ranma often called him/herself Ranko to spend time with his mother, although she doesn’t find out until late in the manga. Eventually Nodoka finds out and declares Ranma to be a man despite the curse, so no one had to commit seppuku.

Raymond Feist‘s fictional realm of Tsuranuanni is based on the real-world Japan and also has the concept of seppuku, but not by that name.

For the most part, seppuku is depicted in popular culture as marking a true warrior’s ethos and the (stereotypical) mystical Eastern understanding of death. The dutiful suicide of seppuku is often seen as a uniquely Japanese cultural trait, although the Western tradition has its share of historical figures who have killed themselves when facing dishonor, death or both at the hands of their enemies.

In Raymond Benson‘s James Bond book The Man with the Red Tattoo, the main villain, Yami Shogun Goro Yoshida commits seppuku just before Bond could capture him. Yasutake Tsukamoto, yakuza leader and Yoshida’s secundant, tells Bond that Yoshida won, because he «robbed Bond of the ultimate victory». Bond tells Tsukamoto that he does not care about it, because «he’s bloody dead and that’s all that matters.»

In Giacomo Puccini‘s opera, Madame Butterfly, the heroine Cio-cio-san, commits Seppuku at the end of the final act.

Unit leaders in computer strategy game Shogun: Total War may commit seppuku if the units they command are defeated in combat too many times.

In the computer game Samurai Warrior: The Battles of Usagi Yojimbo (Firebird Software, 1988), game character Usagi Yojimbo automatically commits seppuku when dishonorable actions performed by the player make karma counter reach zero.

In the computer game Warcraft III the night elf demon hunter, Illidan, commits ritual suicide as part of his death animation.

Microprose’s 1989 role-playing/strategy game Sword of the Samurai allowed a character to commit seppuku following any sudden loss of honor, usually after being captured or recognized whilst attempting murder or treachery against his lord or feudal rivals. At the initial samurai and hatamoto levels, this ‘option’ presents as a capital punishment handed down by the player’s lord; anything short of immediate compliance would see the character and his family (including any heirs) hunted down and executed. In the later stages of the game, daimyo-ranked characters so dishonored were given the option to commit seppuku but were under no compulsion to do so beyond the strategic disadvantages arising from dishonor.

In the fighting game series Tekken and Soul Calibur, the character Yoshimitsu has a move (the «Turning Suicide») wherin he turns away from the enemy and stabs his sword through his stomach and out his back. If the sword connects with Yoshimitsu’s opponent, it causes devastating damage to them, and minor damage to Yoshimitsu himself. However, if it misses, it drains half of Yoshimitsu’s life.

In the action/stealth video game Tom Clancy’s Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory the antagonist, Admiral Toshiro Otomo, wishes for Japan to once again assume the mantle of imperialism and tries to lure the USA and the Koreas into war. When Otomo’s plan falls through, he commits seppuku in front of Sam Fisher rather than be brought to justice. In a ironic twist however, Otomo is saved by Fisher and he is brought to justice.

In the action/stealth videogame «Tenchu: Stealth Assassins«, Lord Gohda orders his ninja to execute a corrupt minister named Kataoka. If the player confronts him as Ayame, he refuses to be insulted by a woman and they fight to the death. But as Rikimaru, Kataoka respects Gohda’s request to be killed and commits seppuku, with Rikimaru acting as his second.

The cult website realultimatepower.net describes a darkly hilarious method of committing seppuku by swallowing a Frisbee.

Ninja Burger‘s website ninjaburger.com, a parody of fast food delivery services, states on their webpage: Guaranteed delivery in 30 minutes or less, or we commit Seppuku!

In the American film Harold and Maude, the character Harold, a young man obsessed with death, fakes his own suicide in a multitude of ways. At one point, he brings out a blade and educates a woman in the art of «hara-kiri» before going through with the (faked) ritual.

In the motion picture Airplane! a japanese man is literally ‘bored to death’ by Ted Stryker (Robert Hays) describing his war record, and commits seppuku by disemboweling himself with a sword while sitting in his airplane seat.

Seppuku is depicted twice on the American film The Last Samurai, at the beginning of the movie after the general of the Japanese newly formed army faces defeat in the hands of Katsumoto’s (played by Ken Watanabe) forces, and later, near the end of the film, with Katsumoto committing seppuku after his army is killed to the last man (all but Nathan Algren, played by Tom Cruise). In the first instance, we see Katsumoto in the role of kaishaku, beheading General Hasegawa to quickly end his suffering. This action comes as a shock to Algren, who sees it as a barbaric form of execution. Finally, defeated on the battlefield it is Algren who helps Katsumoto to end his life with honor by pushing the dagger all the way into his friend’s stomach.

Seppuku and other forms of suicide are looked upon with disfavor in the popular anime/manga series Rurouni Kenshin. Paricularly in the anime series, Kenshin often talks well meaning opponents or people in despair out of suicide, explaining that their deaths will not make up for the mistakes they have made, nor give them any honor. Instead, the best way to atone for ones past or to be truly honorable is to continue living and doing all the good one can in the world. This is Kenshin’s own form of penance for his bloody past as an assassin and the death of his first wife, and several of the characters he speaks to about it comment that living with and struggling to overcome such guilt and doubt is a harder fate than death.

In Internet culture, there is a type of ‘scavenger hunt’ game known as Google Seppuku, where participants type in a (usually Japanese) word or phrase into Google’s image search tool, and look for the most disturbing picture among them. The name derives from the fact that, like modern-day beliefs of committing seppuku, the participants are willfully submitting themselves to something inexplicably awful and painful for glory and honor (in this case, finding the most disturbing picture on the internet that no one can top).

In the Playstation videogame, Bushido Blade, the player can commit seppuku on their own character. It serves no actual function in the game other than adding authenticity.

In the old Commodore 64, Amstrad CPC and ZX Spectrum game, Samurai Warrior: The Battles of Usagi Yojimbo, Usagi would automatically commit seppuku if his karma drops to 0.

In The Ultimate Showdown of Ultimate Destiny, the winning character, Mr. Rogers, commits seppuku.

Seppuku is a common theme in the manga Gin Tama.

In the popular anime/manga One Piece, the CP9 member Kumadori often attempts to commit seppuku for his partners lack of respect or failure, but his superhuman strength prevents it from working.

Towards the end of Hideo Kojima’s MGS:2, a computer A.I. operating under the alias of Colonel Campbell gets infected by a virus and begins spewing nonsensical messages including, «I hear its amazing when the famous purple stuffed worm in flap-jaw space with the tuning fork does a raw blink on Hari Kiri Rock. I need scissors! 61!»

In the Futurama episode The 30% Iron Chef being dishonored (for framing Fry) Dr. Zoidberg grabs a host’s ceremonial Wakazashi, but when he trys to plunge the sword into himself and commit seppuku the blade bends and folds instead of cutting him open.

In the second episode of the Singapore dub of One Piece, Zoro says to Luffy that, if Luffy gets in the way of his dream to be the world’s greatest swordsman, Zoro will have to commit hari-kari, where as in the original japanese it is Luffy who has to commit hara-kiri if he gets in the way.

In Yakitate! Japan, the rather exaggerated samurai bread baker Suwabara Kai mentions seppuku a few times, once saying to his teammate Kawachi Kyosuke who has ruined a bread the team was going to enter in a contest that if he were a real Japanese man, he should take responsibility for his mistake by committing seppuku. Another time Suwabara says that if he loses his Yakitate 9 match against Azuma, he will commit seppuku. He is talked out of this in the end, of course.

In the film Scary Movie 4, the Japanese ambassador to the United Nations committed seppuku upon seeing the US President nude during the demonstration of the reverse-engineered alien heat ray weapon. In this case, it was more out of disgust rather than dishonor.

In the computer game series Wing Commander, the Kilrathi is known to commit ritual suicides akin to seppuku.

In Xenosaga Episode III, Margulis commits seppuku after losing his final battle against Jin.

In the 1998 film The Big Hit The bankrupted father of kidnapped victim Keiko Nishi tries repeatedly to commit seppuku but is interupted by the phone ringing.

In a more adult sketch from the black comedy series Hale & Pace commedian Hale commits seppuku infront of his comedy partner Pace having moments before inadvertedly sliced Pace horizontally in half. With this action being delayed for comic affect and not occuring to Pace until after Hale has died.

In The Adventures of Tintin story The Blue Lotus, Tintin catches sight of a headline in the local newspaper about one of the villans having commited suicide by «hara-kiri» after being exposed as a drug dealing terrorist.

In the video/arcade series Darkstalkers, the character Bishamon can execute a move that, if it connects, forces the opponent to commit seppuku.

See also

- Kamikaze

- Yukio Mishima

- Japanese funeral

- Nakano Seigo

- Jigai

Further reading

- Jack Seward, Hara-Kiri: Japanese Ritual Suicide (Charles E. Tuttle, 1968)

- Seppuku — A Practical Guide (tongue-in-cheek)

- An Account of the Hara-Kiri from Mitford’s «Tales of Old Japan» provides a detailed description: http://www.blackmask.com/thatway/books162c/taja.htm

- The samurai way of death —a chapter from «Samurai: The World of the Warrior» by Dr. Stephen Turnbull

- The Fine Art of Seppuku

- Zuihoden — The mausoleum of Date Masamune — When he died, twenty of his followers killed themselves to serve him in the next life. They lay in state at Zuihoden

- Seppuku and «cruel punishments» at the end of Tokugawa Shogunate [2]

- Tokugawa Shogunate edict banning Junshi (Following one’s lord in death) From the Buke Sho Hatto (1663 AD)—

- «That the custom of following a master in death is wrong and unprofitable is a caution which has been at times given of old; but, owing to the fact that it has not actually been prohibited, the number of those who cut their belly to follow their lord on his decease has become very great. For the future, to those retainers who may be animated by such an idea, their respective lords should intimate, constantly and in very strong terms, their disapproval of the custom. If, notwithstanding this warning, any instance of the practice should occur, it will be deemed that the deceased lord was to blame for unreadiness. Henceforward, moreover, his son and successor will be held to be blameworthy for incompetence, as not having prevented the suicides.»

- SengokuDaimyo.com The website of Samurai Author and Historian Anthony J. Bryant

bn:হারা-কিরি

bs:Seppuku

bg:Сепуку

cs:Seppuku

de:Seppuku

et:Harakiri

es:Seppuku

fr:Seppuku

hr:Seppuku

id:Seppuku

is:Seppuku

he:ספוקו

ka:სეპუკუ

lt:Sepuku

nl:Seppuku

pt:Seppuku

ro:Seppuku

ru:Сэппуку

sl:Seppuku

sr:Сепуку

fi:Seppuku

sv:Harakiri

th:ฮาราคีรี

zh:切腹

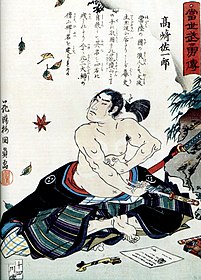

Staged seppuku with ritual attire and kaishaku

| Seppuku | |||

|---|---|---|---|

«Seppuku» in kanji |

|||

| Japanese name | |||

| Kanji | 切腹 | ||

| Hiragana | せっぷく | ||

| Katakana | セップク | ||

|

Seppuku (切腹, ‘cutting [the] belly’), also called hara-kiri (腹切り, lit. ‘abdomen/belly cutting’, a native Japanese kun reading), is a form of Japanese ritualistic suicide by disembowelment. While harakiri refers to the act of disemboweling one’s self, seppuku refers to the ritual and usually would involve decapitation after the act as a sign of mercy. Harakiri refers solely to the act of disembowelment and would only be assigned as a punishment towards acts deemed too heinous for seppuku.[1] It was originally reserved for samurai in their code of honour, but was also practiced by other Japanese people during the Shōwa period[2][3] (particularly officers near the end of World War II) to restore honour for themselves or for their families.[4][5][6] As a samurai practice, seppuku was used voluntarily by samurai to die with honour rather than fall into the hands of their enemies (and likely be tortured), as a form of capital punishment for samurai who had committed serious offences, or performed because they had brought shame to themselves.[1] The ceremonial disembowelment, which is usually part of a more elaborate ritual and performed in front of spectators, consists of plunging a short blade, traditionally a tantō, into the belly and drawing the blade from left to right, slicing the belly open.[7] If the cut is deep enough, it can sever the abdominal aorta, causing a rapid death by blood loss.[citation needed]

The first recorded act of seppuku was performed by Minamoto no Yorimasa during the Battle of Uji in 1180.[8] Seppuku was used by warriors to avoid falling into enemy hands and to attenuate shame and avoid possible torture.[9][10] Samurai could also be ordered by their daimyō (feudal lords) to carry out seppuku. Later, disgraced warriors were sometimes allowed to carry out seppuku rather than be executed in the normal manner.[11] The most common form of seppuku for men was composed of the cutting of the abdomen, and when the samurai was finished, he stretched out his neck for an assistant to sever his spinal cord. It was the assistant’s job to decapitate the samurai in one swing, otherwise it would bring great shame to the assistant and his family. Those who did not belong to the samurai caste were never ordered or expected to carry out seppuku. Samurai generally could carry out the act only with permission.

Sometimes a daimyō was called upon to perform seppuku as the basis of a peace agreement. This weakened the defeated clan so that resistance effectively ceased. Toyotomi Hideyoshi used an enemy’s suicide in this way on several occasions, the most dramatic of which effectively ended a dynasty of daimyōs. When the Hōjō Clan were defeated at Odawara in 1590, Hideyoshi insisted on the suicide of the retired daimyō Hōjō Ujimasa and the exile of his son Ujinao; with this act of suicide, the most powerful daimyō family in eastern Japan was completely defeated.

Etymology[edit]

Samurai about to perform seppuku

The term seppuku is derived from the two Sino-Japanese roots setsu 切 («to cut», from Middle Chinese tset; compare Mandarin qiē and Cantonese chit) and fuku 腹 («belly», from MC pjuwk; compare Mandarin fù and Cantonese fūk).

It is also known as harakiri (腹切り, «cutting the stomach»;[12] often misspelled/mispronounced «hiri-kiri» or «hari-kari» by American English speakers).[13] Harakiri is written with the same kanji as seppuku but in reverse order with an okurigana. In Japanese, the more formal seppuku, a Chinese on’yomi reading, is typically used in writing, while harakiri, a native kun’yomi reading, is used in speech. As Ross notes,

It is commonly pointed out that hara-kiri is a vulgarism, but this is a misunderstanding. Hara-kiri is a Japanese reading or Kun-yomi of the characters; as it became customary to prefer Chinese readings in official announcements, only the term seppuku was ever used in writing. So hara-kiri is a spoken term, but only to commoners and seppuku a written term, but spoken amongst higher classes for the same act.[14]

The practice of performing seppuku at the death of one’s master, known as oibara (追腹 or 追い腹, the kun’yomi or Japanese reading) or tsuifuku (追腹, the on’yomi or Chinese reading), follows a similar ritual.

The word jigai (自害) means «suicide» in Japanese. The modern word for suicide is jisatsu (自殺). In some popular western texts, such as martial arts magazines, the term is associated with suicide of samurai wives.[15] The term was introduced into English by Lafcadio Hearn in his Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation,[16] an understanding which has since been translated into Japanese.[17] Joshua S. Mostow notes that Hearn misunderstood the term jigai to be the female equivalent of seppuku.[18]

Ritual[edit]

A tantō prepared for seppuku

The practice was not standardized until the 17th century. In the 12th and 13th centuries, such as with the seppuku of Minamoto no Yorimasa, the practice of a kaishakunin (idiomatically, his «second») had not yet emerged, thus the rite was considered far more painful. The defining characteristic was plunging either the tachi (longsword), wakizashi (shortsword) or tantō (knife) into the gut and slicing the abdomen horizontally. In the absence of a kaishakunin, the samurai would then remove the blade and stab himself in the throat, or fall (from a standing position) with the blade positioned against his heart.

During the Edo period (1600–1867), carrying out seppuku came to involve an elaborate, detailed ritual. This was usually performed in front of spectators if it was a planned seppuku, as opposed to one performed on a battlefield. A samurai was bathed in cold water (to prevent excessive bleeding), dressed in a white kimono called the shiro-shōzoku (白装束) and served his favorite foods for a last meal. When he had finished, the knife and cloth were placed on another sanbo and given to the warrior. Dressed ceremonially, with his sword placed in front of him and sometimes seated on special clothes, the warrior would prepare for death by writing a death poem. He would probably consume an important ceremonial drink of sake. He would also give his attendant a cup meant for sake.[19][20]

General Akashi Gidayu preparing to carry out seppuku after losing a battle for his master in 1582. He had just written his death poem, which is also visible in the upper right corner. By Tsukioka Yoshitoshi around 1890.

With his selected kaishakunin standing by, he would open his kimono, take up his tantō – which the samurai held by the blade with a cloth wrapped around so that it would not cut his hand and cause him to lose his grip – and plunge it into his abdomen, making a left-to-right cut. The kaishakunin would then perform kaishaku, a cut in which the warrior was partially decapitated. The maneuver should be done in the manners of dakikubi (lit. «embraced head»), in which way a slight band of flesh is left attaching the head to the body, so that it can be hung in front as if embraced. Because of the precision necessary for such a maneuver, the second was a skilled swordsman. The principal and the kaishakunin agreed in advance when the latter was to make his cut. Usually dakikubi would occur as soon as the dagger was plunged into the abdomen. Over time, the process became so highly ritualized that as soon as the samurai reached for his blade the kaishakunin would strike. Eventually even the blade became unnecessary and the samurai could reach for something symbolic like a fan, and this would trigger the killing stroke from his second. The fan was likely used when the samurai was too old to use the blade or in situations where it was too dangerous to give him a weapon.[21]

This elaborate ritual evolved after seppuku had ceased being mainly a battlefield or wartime practice and became a para-judicial institution. The second was usually, but not always, a friend. If a defeated warrior had fought honorably and well, an opponent who wanted to salute his bravery would volunteer to act as his second.

In the Hagakure, Yamamoto Tsunetomo wrote:

From ages past it has been considered an ill-omen by samurai to be requested as kaishaku. The reason for this is that one gains no fame even if the job is well done. Further, if one should blunder, it becomes a lifetime disgrace.

In the practice of past times, there were instances when the head flew off. It was said that it was best to cut leaving a little skin remaining so that it did not fly off in the direction of the verifying officials.

A specialized form of seppuku in feudal times was known as kanshi (諫死, «remonstration death/death of understanding»), in which a retainer would commit suicide in protest of a lord’s decision. The retainer would make one deep, horizontal cut into his abdomen, then quickly bandage the wound. After this, the person would then appear before his lord, give a speech in which he announced the protest of the lord’s action, then reveal his mortal wound. This is not to be confused with funshi (憤死, indignation death), which is any suicide made to protest or state dissatisfaction.[citation needed]

Some samurai chose to perform a considerably more taxing form of seppuku known as jūmonji giri (十文字切り, «cross-shaped cut»), in which there is no kaishakunin to put a quick end to the samurai’s suffering. It involves a second and more painful vertical cut on the belly. A samurai performing jūmonji giri was expected to bear his suffering quietly until he bled to death, passing away with his hands over his face.[22]

Female ritual suicide[edit]

Female ritual suicide (incorrectly referred to in some English sources as jiigai), was practiced by the wives of samurai who have performed seppuku or brought dishonor.[23][24]

Some women belonging to samurai families committed suicide by cutting the arteries of the neck with one stroke, using a knife such as a tantō or kaiken. The main purpose was to achieve a quick and certain death in order to avoid capture. Before committing suicide, a woman would often tie her knees together so her body would be found in a “dignified” pose, despite the convulsions of death. Invading armies would often enter homes to find the lady of the house seated alone, facing away from the door. On approaching her, they would find that she had ended her life long before they reached her.[citation needed]

The wife of Onodera Junai, one of the Forty-seven Ronin, prepares for her suicide; note the legs tied together, a feature of female seppuku to ensure a decent posture in death

History[edit]