1. Положение серы в периодической системе химических элементов

2. Электронное строение атома серы

3. Физические свойства и нахождение в природе

4. Соединения серы

5. Способы получения

6. Химические свойства

6.1. Взаимодействие с простыми веществами

6.1.1. Взаимодействие с кислородом

6.1.2. Взаимодействие с галогенами

6.1.3. Взаимодействие с серой и фосфором

6.1.4. Взаимодействие с металлами

6.1.5. Взаимодействие с водородом

6.2. Взаимодействие со сложными веществами

6.2.1. Взаимодействие с окислителями

6.2.2. Взаимодействие с щелочами

Сероводород

1. Строение молекулы и физические свойства

2. Способы получения

3. Химические свойства

3.1. Кислотные свойства

3.2. Взаимодействие с кислородом

3.3. Восстановительные свойства

3.4. Взаимодействие с солями тяжелых металлов

Сульфиды

Способы получения сульфидов

Химические свойства сульфидов

Оксиды серы

1. Оксид серы (IV)

2. Оксид серы (VI)

Серная кислота

1. Строение молекулы и физические свойства

2. Способы получения

3. Химические свойства

3.1. Диссоциация серной кислоты

3.2. Основные свойства серной кислоты

3.3. Взаимодействие с солями более слабых кислот

3.4. Разложение при нагревании

3.5. Взаимодействие с солями

3.6. Качественная реакция на сульфат-ионы

3.7. Окислительные свойства серной кислоты

Сернистая кислота

Соли серной кислоты – сульфаты

Сера

Положение в периодической системе химических элементов

Сера расположена в главной подгруппе VI группы (или в 15 группе в современной форме ПСХЭ) и в третьем периоде периодической системы химических элементов Д.И. Менделеева.

Электронное строение серы

Электронная конфигурация серы в основном состоянии:

Атом серы содержит на внешнем энергетическом уровне 2 неспаренных электрона и две неподеленные электронные пары в основном энергетическом состоянии. Следовательно, атом серы может образовывать 2 связи по обменному механизму, как и кислород. Однако, в отличие от кислорода, за счет вакантной 3d орбитали атом серы может переходить в возбужденные энергетические состояния. Электронная конфигурация серы в первом возбужденном состоянии:

Электронная конфигурация серы во втором возбужденном состоянии:

Таким образом, максимальная валентность серы в соединениях равна VI (в отличие от кислорода). Также для серы характерна валентность — IV.

Степени окисления атома серы – от -2 до +4. Характерные степени окисления -2, 0, +4, +6.

Физические свойства и нахождение в природе

Сера образует различные простые вещества (аллотропные модификации).

Наиболее устойчивая модификация серы – ромбическая сера S8. Это хрупкое вещество желтого цвета.

Моноклинная сера – это аллотропная модификация серы, в которой атомы соединены в циклы в виде «короны». Это твердое вещество, состоящее из темно-желтых игл, устойчивое при температуре более 96оС, а при обычной температуре превращающееся в ромбическую серу.

Пластическая сера – это вещество, состоящее из длинных полимерных цепей. Коричневая резиноподобная аморфная масса, нерастворимая в воде.

В природе сера встречается:

- в самородном виде;

- в составе сульфидов (сульфид цинка ZnS, пирит FeS2, сульфид ртути HgS — киноварь и др.)

- в составе сульфатов (CaSO4·2H2O гипс, Na2SO4·10H2O — глауберова соль)

Соединения серы

Типичные соединения серы:

| Степень окисления | Типичные соединения |

| +6 | Оксид серы(VI) SO3

Серная кислота H2SO4 Сульфаты MeSO4 Галогенангидриды: SО2Cl2 |

| +4 | Оксид серы (IV) SO2

Сернистая кислота H2SO3 Сульфиты MeSO3 Гидросульфиты MeHSO3 Галогенангидриды: SOCl2 |

| –2 | Сероводород H2S

Сульфиды металлов MeS |

Способы получения серы

1. В промышленных масштабах серу получают открытым способом на месторождениях самородной серы, либо из вулканов. Из серной руды серу получают также пароводяными, фильтрационными, термическими, центрифугальными и экстракционными методами. Пароводяной метод — это выплавление из руды с помощью водяного пара.

2. Способ получения серы в лаборатории – неполное окисление сероводорода.

2H2S + O2 → 2S + 2H2O

3. Еще один способ получения серы – взаимодействие сероводорода с оксидом серы (IV):

2H2S + SO2 → 3S + 2H2O

Химические свойства серы

В нормальных условиях химическая активность серы невелика: при нагревании сера активна, и может быть как окислителем, так и восстановителем.

1. Сера проявляет свойства окислителя (при взаимодействии с элементами, которые расположены ниже и левее в Периодической системе) и свойства восстановителя (с элементами, расположенными выше и правее). Поэтому сера реагирует с металлами и неметаллами.

1.1. При горении серы на воздухе образуется оксид серы (IV):

S + O2 → SO2

1.2. При взаимодействии серы с галогенами (со всеми, кроме йода) образуются галогениды серы:

S + Cl2 → SCl2 (S2Cl2)

S + 3F2 → SF6

1.3. При взаимодействии фосфора и углерода с серой образуются сульфиды фосфора и сероуглерод:

2P + 3S → P2S3

2P + 5S → P2S5

2S + C → CS2

1.4. При взаимодействии с металлами сера проявляет свойства окислителя, продукты реакции называют сульфидами. С щелочными металлами сера реагирует без нагревания, а с остальными металлами (кроме золота и платины) – только при нагревании.

Например, железо и ртуть реагируют с серой с образованием сульфидов железа (II) и ртути:

S + Fe → FeS

S + Hg → HgS

Еще пример: алюминий взаимодействует с серой с образованием сульфида алюминия:

3S + 2Al → Al2S3

1.5. С водородом сера взаимодействует при нагревании с образованием сероводорода:

S + H2 → H2S

2. Со сложными веществами сера реагирует, также проявляя окислительные и восстановительные свойства. Сера диспропорционирует при взаимодействии с некоторыми веществами.

2.1. При взаимодействии с окислителями сера окисляется до оксида серы (IV) или до серной кислоты (если реакция протекает в растворе).

Например, азотная кислота окисляет серу до серной кислоты:

S + 6HNO3 → H2SO4 + 6NO2 + 2H2O

Серная кислота также окисляет серу. Но, поскольку S+6 не может окислить серу же до степени окисления +6, образуется оксид серы (IV):

S + 2H2SO4 → 3SO2 + 2H2O

Соединения хлора, например, бертолетова соль, также окисляют серу до +4:

3S + 2KClO3 → 3SO2 + 2KCl

Взаимодействие серы с сульфитами (при кипячении) приводит к образованию тиосульфатов:

S + Na2SO3 → Na2S2O3

2.2. При растворении в щелочах сера диспропорционирует до сульфита и сульфида.

Например, сера реагирует с гидроксидом натрия:

S + 6NaOH → Na2SO3 + 2Na2S + 3H2O

При взаимодействии с перегретым паром сера диспропорционирует:

3S + 2H2O (пар) → 2H2S + SO2

Сероводород

Строение молекулы и физические свойства

Сероводород H2S – это бинарное соединение водорода с серой, относится к летучим водородным соединениям. Следовательно, сероводород бесцветный ядовитый газ, с запахом тухлых яиц. Образуется при гниении. В твердом состоянии имеет молекулярную кристаллическую решетку.

Геометрическая форма молекулы сероводорода похожа на структуру воды — уголковая молекула. Но валентный угол H-S-H меньше, чем угол H-O-H в воде и составляет 92,1о.

Способы получения сероводорода

В лаборатории сероводород получают действием минеральных кислот на сульфиды металлов, расположенных в ряду напряжений левее железа.

Например, при действии соляной кислоты на сульфид железа (II):

FeS + 2HCl → FeCl2 + H2S↑

Еще один способ получения сероводорода – прямой синтез из водорода и серы:

S + H2 → H2S

Еще один лабораторный способ получения сероводорода – нагревание парафина с серой.

Видеоопыт получения и обнаружения сероводорода можно посмотреть здесь.

Химические свойства сероводорода

1. В водном растворе сероводород проявляет слабые кислотные свойства. Взаимодействует с сильными основаниями, образуя сульфиды и гидросульфиды:

Например, сероводород реагирует с гидроксидом натрия:

H2S + 2NaOH → Na2S + 2H2O

H2S + NaOH → NaНS + H2O

2. Сероводород H2S – очень сильный восстановитель за счет серы в степени окисления -2. При недостатке кислорода и в растворе H2S окисляется до свободной серы (раствор мутнеет):

2H2S + O2 → 2S + 2H2O

В избытке кислорода:

2H2S + 3O2 → 2SO2 + 2H2O

3. Как сильный восстановитель, сероводород легко окисляется под действием окислителей.

Например, бром и хлор окисляют сероводород до молекулярной серы:

H2S + Br2 → 2HBr + S↓

H2S + Cl2 → 2HCl + S↓

Под действием избытка хлора в водном растворе сероводород окисляется до серной кислоты:

H2S + 4Cl2 + 4H2O → H2SO4 + 8HCl

Например, азотная кислота окисляет сероводород до молекулярной серы:

H2S + 2HNO3(конц.) → S + 2NO2 + 2H2O

При кипячении сера окисляется до серной кислоты:

H2S + 8HNO3(конц.) → H2SO4 + 8NO2 + 4H2O

Прочие окислители окисляют сероводород, как правило, до молекулярной серы.

Например, оксид серы (IV) окисляет сероводород:

2H2S + SO2 → 3S + 2H2O

Соединения железа (III) также окисляют сероводород:

H2S + 2FeCl3 → 2FeCl2 + S + 2HCl

Бихроматы, хроматы и прочие окислители также окисляют сероводород до молекулярной серы:

3H2S + K2Cr2O7 + 4H2SO4 → 3S + Cr2(SO4)3 + K2SO4 + 7H2O

2H2S + 4Ag + O2 → 2Ag2S + 2H2O

Серная кислота окисляет сероводород либо до молекулярной серы:

H2S + H2SO4(конц.) → S + SO2 + 2H2O

Либо до оксида серы (IV):

H2S + 3H2SO4(конц.) → 4SO2 + 4H2O

4. Сероводород в растворе реагирует с растворимыми солями тяжелых металлов: меди, серебра, свинца, ртути, образуя черные сульфиды, нерастворимые ни в воде, ни в минеральных кислотах.

Например, сероводород реагирует в растворе с нитратом свинца (II). при этом образуется темно-коричневый (почти черный) осадок, нерастворимый ни в воде, ни в минеральных кислотах:

H2S + Pb(NO3)2 → PbS + 2HNO3

Взаимодействие с нитратом свинца в растворе – это качественная реакция на сероводород и сульфид-ионы.

Видеоопыт взаимодействия сероводорода с нитратом свинца можно посмотреть здесь.

Сульфиды

Сульфиды – это бинарные соединения серы и металлов или некоторых неметаллов, соли сероводородной кислоты.

По растворимости в воде и кислотах сульфиды разделяют на растворимые в воде, нерастворимые в воде, но растворимые в минеральных кислотах, нерастворимые ни в воде, ни в минеральных кислотах, гидролизуемые водой.

| Растворимые в воде | Нерастворимые в воде, но растворимые в минеральных кислотах | Нерастворимые ни в воде, ни в минеральных кислотах (только в азотной и серной конц.) | Разлагаемые водой, в растворе не существуют |

| Сульфиды щелочных металлов и аммония | Сульфиды прочих металлов, расположенных до железа в ряду активности. Белые и цветные сульфиды (ZnS, MnS, FeS, CdS) | Черные сульфиды (CuS, HgS, PbS, Ag2S, NiS, CoS) | Сульфиды трехвалентных металлов (алюминия и хрома (III)) |

| Реагируют с минеральными кислотами с образованием сероводорода | Не реагируют с минеральными кислотами, сероводород получить напрямую нельзя |

Разлагаются водой |

|

| ZnS + 2HCl → ZnCl2 + H2S |

Al2S3 + 6H2O → 2Al(OH)3 + 3H2S |

Способы получения сульфидов

1. Сульфиды получают при взаимодействии серы с металлами. При этом сера проявляет свойства окислителя.

Например, сера взаимодействует с магнием и кальцием:

S + Mg → MgS

S + Ca → CaS

Сера взаимодействует с натрием:

S + 2Na → Na2S

2. Растворимые сульфиды можно получить при взаимодействии сероводорода и щелочей.

Например, гидроксида калия с сероводородом:

H2S + 2KOH → K2S + 2H2O

3. Нерастворимые сульфиды получают взаимодействием растворимых сульфидов с солями (любые сульфиды) или взаимодействием сероводорода с солями (только черные сульфиды).

Например, при взаимодействии нитрата меди и сероводорода:

Pb(NO3)2 + Н2S → 2НNO3 + PbS

Еще пример: взаимодействие сульфата цинка с сульфидом натрия:

ZnSO4 + Na2S → Na2SO4 + ZnS

Химические свойства сульфидов

1. Растворимые сульфиды гидролизуются по аниону, среда водных растворов сульфидов щелочная:

K2S + H2O ⇄ KHS + KOH

S2– + H2O ⇄ HS– + OH–

2. Сульфиды металлов, расположенных в ряду напряжений левее железа (включительно), растворяются в сильных минеральных кислотах.

Например, сульфид кальция растворяется в соляной кислоте:

CaS + 2HCl → CaCl2 + H2S

А сульфид никеля, например, не растворяется:

NiS + HСl ≠

3. Нерастворимые сульфиды растворяются в концентрированной азотной кислоте или концентрированной серной кислоте. При этом сера окисляется либо до простого вещества, либо до сульфата.

Например, сульфид меди (II) растворяется в горячей концентрированной азотной кислоте:

CuS + 8HNO3 → CuSO4 + 8NO2 + 4H2O

или горячей концентрированной серной кислоте:

CuS + 4H2SO4(конц. гор.) → CuSO4 + 4SO2 + 4H2O

4. Сульфиды проявляют восстановительные свойства и окисляются пероксидом водорода, хлором и другими окислителями.

Например, сульфид свинца (II) окисляется пероксидом водорода до сульфата свинца (II):

PbS + 4H2O2 → PbSO4 + 4H2O

Еще пример: сульфид меди (II) окисляется хлором:

СuS + Cl2 → CuCl2 + S

5. Сульфиды горят (обжиг сульфидов). При этом образуются оксиды металла и серы (IV).

Например, сульфид меди (II) окисляется кислородом до оксида меди (II) и оксида серы (IV):

2CuS + 3O2 → 2CuO + 2SO2

Аналогично сульфид хрома (III) и сульфид цинка:

2Cr2S3 + 9O2 → 2Cr2O3 + 6SO2

2ZnS + 3O2 → 2SO2 + ZnO

6. Реакции сульфидов с растворимыми солями свинца, серебра, меди используют как качественные на ион S2−.

Сульфиды свинца, серебра и меди — черные осадки, нерастворимые в воде и минеральных кислотах:

Na2S + Pb(NO3)2 → PbS↓ + 2NaNO3

Na2S + 2AgNO3 → Ag2S↓ + 2NaNO3

Na2S + Cu(NO3)2 → CuS↓ + 2NaNO3

7. Сульфиды трехвалентных металлов (алюминия и хрома) разлагаются водой (необратимый гидролиз).

Например, сульфид алюминия разлагается до гидроксида алюминия и сероводорода:

Al2S3 + 6H2O → 2Al(OH)3 + 3H2S

Разложение происходит и взаимодействии солей трехвалентных металлов с сульфидами щелочных металлов.

Например, сульфид натрия реагирует с хлоридом алюминия в растворе. Но сульфид алюминия не образуется, а сразу же необратимо гидролизуется (разлагается) водой:

3Na2S + 2AlCl3 + 6H2O → 2Al(OH)3 + 3H2S + 6NaCl

Оксиды серы

| Оксиды серы | Цвет | Фаза | Характер оксида |

| SO2 Оксид сера (IV), сернистый газ | бесцветный | газ | кислотный |

| SO3 Оксид серы (VI), серный ангидрид | бесцветный | жидкость | кислотный |

Оксид серы (IV)

Оксид серы (IV) – это кислотный оксид. Бесцветный газ с резким запахом, хорошо растворимый в воде.

Cпособы получения оксида серы (IV):

1. Сжигание серы на воздухе:

S + O2 → SO2

2. Горение сульфидов и сероводорода:

2H2S + 3O2 → 2SO2 + 2H2O

2CuS + 3O2 → 2SO2 + 2CuO

3. Взаимодействие сульфитов с более сильными кислотами:

Например, сульфит натрия взаимодействует с серной кислотой:

Na2SO3 + H2SO4 → Na2SO4 + SO2 + H2O

4. Обработка концентрированной серной кислотой неактивных металлов.

Например, взаимодействие меди с концентрированной серной кислотой:

Cu + 2H2SO4 → CuSO4 + SO2 + 2H2O

Химические свойства оксида серы (IV):

Оксид серы (IV) – это типичный кислотный оксид. За счет серы в степени окисления +4 проявляет свойства окислителя и восстановителя.

1. Как кислотный оксид, сернистый газ реагирует с щелочами и оксидами щелочных и щелочноземельных металлов.

Например, оксид серы (IV) реагирует с гидроксидом натрия. При этом образуется либо кислая соль (при избытке сернистого газа), либо средняя соль (при избытке щелочи):

SO2 + 2NaOH(изб) → Na2SO3 + H2O

SO2(изб) + NaOH → NaHSO3

Еще пример: оксид серы (IV) реагирует с основным оксидом натрия:

SO2 + Na2O → Na2SO3

2. При взаимодействии с водой SO2 образует сернистую кислоту. Реакция обратимая, т.к. сернистая кислота в водном растворе в значительной степени распадается на оксид и воду.

SO2 + H2O ↔ H2SO3

3. Наиболее ярко выражены восстановительные свойства SO2. При взаимодействии с окислителями степень окисления серы повышается.

Например, оксид серы окисляется кислородом на катализаторе в жестких условиях. Реакция также сильно обратимая:

2SO2 + O2 ↔ 2SO3

Сернистый ангидрид обесцвечивает бромную воду:

SO2 + Br2 + 2H2O → H2SO4 + 2HBr

Азотная кислота очень легко окисляет сернистый газ:

SO2 + 2HNO3 → H2SO4 + 2NO2

Озон также окисляет оксид серы (IV):

SO2 + O3 → SO3 + O2

Качественная реакция на сернистый газ и на сульфит-ион – обесцвечивание раствора перманганата калия:

5SO2 + 2H2O + 2KMnO4 → 2H2SO4 + 2MnSO4 + K2SO4

Оксид свинца (IV) также окисляет сернистый газ:

SO2 + PbO2 → PbSO4

4. В присутствии сильных восстановителей SO2 способен проявлять окислительные свойства.

Например, при взаимодействии с сероводородом сернистый газ восстанавливается до молекулярной серы:

SO2 + 2Н2S → 3S + 2H2O

Оксид серы (IV) окисляет угарный газ и углерод:

SO2 + 2CO → 2СО2 + S

SO2 + С → S + СO2

Оксид серы (VI)

Оксид серы (VI) – это кислотный оксид. При обычных условиях – бесцветная ядовитая жидкость. На воздухе «дымит», сильно поглощает влагу.

Способы получения. Оксид серы (VI) получают каталитическим окислением оксида серы (IV) кислородом.

2SO2 + O2 ↔ 2SO3

Сернистый газ окисляют и другие окислители, например, озон или оксид азота (IV):

SO2 + O3 → SO3 + O2

SO2 + NO2 → SO3 + NO

Еще один способ получения оксида серы (VI) – разложение сульфата железа (III):

Fe2(SO4)3 → Fe2O3 + 3SO3

Химические свойства оксида серы (VI)

1. Оксид серы (VI) активно поглощает влагу и реагирует с водой с образованием серной кислоты:

SO3 + H2O → H2SO4

2. Серный ангидрид является типичным кислотным оксидом, взаимодействует с щелочами и основными оксидами.

Например, оксид серы (VI) взаимодействует с гидроксидом натрия. При этом образуются средние или кислые соли:

SO3 + 2NaOH(избыток) → Na2SO4 + H2O

SO3(избыток) + NaOH → NaHSO4

Еще пример: оксид серы (VI) взаимодействует с оксидом оксидом (при сплавлении):

SO3 + MgO → MgSO4

3. Серный ангидрид – очень сильный окислитель, так как сера в нем имеет максимальную степень окисления (+6). Он энергично взаимодействует с такими восстановителями, как иодид калия, сероводород или фосфор:

SO3 + 2KI → I2 + K2SO3

3SO3 + H2S → 4SO2 + H2O

5SO3 + 2P → P2O5 + 5SO2

4. Растворяется в концентрированной серной кислоте, образуя олеум – раствор SO3 в H2SO4.

Серная кислота

Строение молекулы и физические свойства

Серная кислота H2SO4 – это сильная кислота, двухосновная, прочная и нелетучая. При обычных условиях серная кислота – тяжелая маслянистая жидкость, хорошо растворимая в воде.

Растворение серной кислоты в воде сопровождается выделением значительного количества теплоты. Поэтому по правилам безопасности в лаборатории при смешивании серной кислоты и воды мы добавляем серную кислоту в воду небольшими порциями при постоянном перемешивании.

Валентность серы в серной кислоте равна VI.

Способы получения

1. Серную кислоту в промышленности производят из серы, сульфидов металлов, сероводорода и др. Один из вариантов — производство серной кислоты из пирита FeS2.

Основные стадии получения серной кислоты :

- Сжигание или обжиг серосодержащего сырья в кислороде с получением сернистого газа.

- Очистка полученного газа от примесей.

- Окисление сернистого газа в серный ангидрид.

- Взаимодействие серного ангидрида с водой.

Рассмотрим основные аппараты, используемые при производстве серной кислоты из пирита (контактный метод):

| Аппарат | Назначение и уравненяи реакций |

| Печь для обжига | 4FeS2 + 11O2 → 2Fe2O3 + 8SO2 + Q

Измельченный очищенный пирит сверху засыпают в печь для обжига в «кипящем слое». Снизу (принцип противотока) пропускают воздух, обогащенный кислородом, для более полного обжига пирита. Температура в печи для обжига достигает 800оС |

| Циклон | Из печи выходит печной газ, который состоит из SO2, кислорода, паров воды и мельчайших частиц оксида железа. Такой печной газ очищают от примесей. Очистку печного газа проводят в два этапа. Первый этап — очистка газа в циклоне. При этом за счет центробежной силы твердые частички ссыпаются вниз. |

| Электрофильтр | Второй этап очистки газа проводится в электрофильтрах. При этом используется электростатическое притяжение, частицы огарка прилипают к наэлектризованным пластинам электрофильтра). |

| Сушильная башня | Осушку печного газа проводят в сушильной башне – снизу вверх поднимается печной газ, а сверху вниз льется концентрированная серная кислота. |

| Теплообменник | Очищенный обжиговый газ перед поступлением в контактный аппарат нагревают за счет теплоты газов, выходящих из контактного аппарата. |

| Контактный аппарат | 2SO2 + O2 ↔ 2SO3 + Q

В контактном аппарате производится окисление сернистого газа до серного ангидрида. Процесс является обратимым. Поэтому необходимо выбрать оптимальные условия протекания прямой реакции (получения SO3):

Как только смесь оксида серы и кислорода достигнет слоев катализатора, начинается процесс окисления SO2 в SO3. Образовавшийся оксид серы SO3 выходит из контактного аппарата и через теплообменник попадает в поглотительную башню. |

| Поглотительная башня | Получение H2SO4 протекает в поглотительной башне.

Однако, если для поглощения оксида серы использовать воду, то образуется серная кислота в виде тумана, состоящего из мельчайших капелек серной кислоты. Для того, чтобы не образовывался сернокислотный туман, используют 98%-ную концентрированную серную кислоту. Оксид серы очень хорошо растворяется в такой кислоте, образуя олеум: H2SO4·nSO3. nSO3 + H2SO4 → H2SO4·nSO3 Образовавшийся олеум сливают в металлические резервуары и отправляют на склад. Затем олеумом заполняют цистерны, формируют железнодорожные составы и отправляют потребителю. |

Общие научные принципы химического производства:

- Непрерывность.

- Противоток

- Катализ

- Увеличение площади соприкосновения реагирующих веществ.

- Теплообмен

- Рациональное использование сырья

Химические свойства

Серная кислота – это сильная двухосновная кислота.

1. Серная кислота практически полностью диссоциирует в разбавленном в растворе по первой ступени:

H2SO4 ⇄ H+ + HSO4–

По второй ступени серная кислота диссоциирует частично, ведет себя, как кислота средней силы:

HSO4– ⇄ H+ + SO42–

2. Серная кислота реагирует с основными оксидами, основаниями, амфотерными оксидами и амфотерными гидроксидами.

Например, серная кислота взаимодействует с оксидом магния:

H2SO4 + MgO → MgSO4 + H2O

Еще пример: при взаимодействии серной кислоты с гидроксидом калия образуются сульфаты или гидросульфаты:

H2SO4 + КОН → KHSО4 + H2O

H2SO4 + 2КОН → К2SО4 + 2H2O

Серная кислота взаимодействует с амфотерным гидроксидом алюминия:

3H2SO4 + 2Al(OH)3 → Al2(SO4)3 + 6H2O

3. Серная кислота вытесняет более слабые из солей в растворе (карбонаты, сульфиды и др.). Также серная кислота вытесняет летучие кислоты из их солей (кроме солей HBr и HI).

Например, серная кислота взаимодействует с гидрокарбонатом натрия:

Н2SO4 + 2NaHCO3 → Na2SO4 + CO2 + H2O

Или с силикатом натрия:

H2SO4 + Na2SiO3 → Na2SO4 + H2SiO3

Концентрированная серная кислота реагирует с твердым нитратом натрия. При этом менее летучая серная кислота вытесняет азотную кислоту:

NaNO3 (тв.) + H2SO4 → NaHSO4 + HNO3

Аналогично – концентрированная серная кислота вытесняет хлороводород из твердых хлоридов, например, хлорида натрия:

NaCl(тв.) + H2SO4 → NaHSO4 + HCl

4. Также серная кислота вступает в обменные реакции с солями.

Например, серная кислота взаимодействует с хлоридом бария:

H2SO4 + BaCl2 → BaSO4 + 2HCl

5. Разбавленная серная кислота взаимодействует с металлами, которые расположены в ряду активности металлов до водорода. При этом образуются соль и водород.

Например, серная кислота реагирует с железом. При этом образуется сульфат железа (II):

H2SO4(разб.) + Fe → FeSO4 + H2

Серная кислота взаимодействует с аммиаком с образованием солей аммония:

H2SO4 + NH3 → NH4HSO4

Концентрированная серная кислота является сильным окислителем. При этом она обычно восстанавливается до сернистого газа SO2. С активными металлами может восстанавливаться до серы S, или сероводорода Н2S.

Железо Fe, алюминий Al, хром Cr пассивируются концентрированной серной кислотой на холоде. При нагревании реакция возможна.

6H2SO4(конц.) + 2Fe → Fe2(SO4)3 + 3SO2 + 6H2O

6H2SO4(конц.) + 2Al → Al2(SO4)3 + 3SO2 + 6H2O

При взаимодействии с неактивными металлами концентрированная серная кислота восстанавливается до сернистого газа:

2H2SO4(конц.) + Cu → CuSO4 + SO2 ↑ + 2H2O

2H2SO4(конц.) + Hg → HgSO4 + SO2 ↑ + 2H2O

2H2SO4(конц.) + 2Ag → Ag2SO4 + SO2↑+ 2H2O

При взаимодействии с щелочноземельными металлами и магнием концентрированная серная кислота восстанавливается до серы:

3Mg + 4H2SO4 → 3MgSO4 + S + 4H2O

При взаимодействии с щелочными металлами и цинком концентрированная серная кислота восстанавливается до сероводорода:

5H2SO4(конц.) + 4Zn → 4ZnSO4 + H2S↑ + 4H2O

6. Качественная реакция на сульфат-ионы – взаимодействие с растворимыми солями бария. При этом образуется белый кристаллический осадок сульфата бария:

BaCl2 + Na2SO4 → BaSO4↓ + 2NaCl

Видеоопыт взаимодействия хлорида бария и сульфата натрия в растворе (качественная реакция на сульфат-ион) можно посмотреть здесь.

7. Окислительные свойства концентрированной серной кислоты проявляются и при взаимодействии с неметаллами.

Например, концентрированная серная кислота окисляет фосфор, углерод, серу. При этом серная кислота восстанавливается до оксида серы (IV):

5H2SO4(конц.) + 2P → 2H3PO4 + 5SO2↑ + 2H2O

2H2SO4(конц.) + С → СО2↑ + 2SO2↑ + 2H2O

2H2SO4(конц.) + S → 3SO2 ↑ + 2H2O

Уже при комнатной температуре концентрированная серная кислота окисляет галогеноводороды и сероводород:

3H2SO4(конц.) + 2KBr → Br2↓ + SO2↑ + 2KHSO4 + 2H2O

5H2SO4(конц.) + 8KI → 4I2↓ + H2S↑ + K2SO4 + 4H2O

H2SO4(конц.) + 3H2S → 4S↓ + 4H2O

Сернистая кислота

Сернистая кислота H2SO3 – это двухосновная кислородсодержащая кислота. При нормальных условиях — неустойчивое вещество, которое распадается на диоксид серы и воду.

Валентность серы в сернистой кислоте равна IV, а степень окисления +4.

Химические свойства

1. Сернистая кислота H2SO3 в водном растворе – двухосновная кислота средней силы. Частично диссоциирует по двум ступеням:

H2SO3 ↔ HSO3– + H+

HSO3– ↔ SO32– + H+

2. Сернистая кислота самопроизвольно распадается на диоксид серы и воду:

H2SO3 ↔ SO2 + H2O

Соли серной кислоты – сульфаты

Серная кислота образует два типа солей: средние – сульфаты, кислые – гидросульфаты.

1. Качественная реакция на сульфат-ионы – взаимодействие с растворимыми солями бария. При этом образуется белый кристаллический осадок сульфата бария:

BaCl2 + Na2SO4 → BaSO4↓ + 2NaCl

Видеоопыт взаимодействия хлорида бария и сульфата натрия в растворе (качественная реакция на сульфат-ион) можно посмотреть здесь.

2. Сульфаты таких металлов, как медь Cu, алюминий Al, цинк Zn, хром Cr, железо (II) Fe подвергаются термическому разложению на оксид металла, диоксид серы SO2 и кислород O2;

2CuSO4 → 2CuO + SO2 + O2 (SO3)

2Al2(SO4)3 → 2Al2O3 + 6SO2 + 3O2

2ZnSO4 → 2ZnO + SO2 + O2

2Cr2(SO4)3 → 2Cr2O3 + 6SO2 + 3O2

При разложении сульфата железа (II) в FeSO4 Fe (II) окисляется до Fe (III)

4FeSO4 → 2Fe2O3 + 4SO2 + O2

Сульфаты самых тяжелых металлов разлагаются до металла.

3. За счет серы со степенью окисления +6 сульфаты проявляют окислительные свойства и могут взаимодействовать с восстановителями.

Например, сульфат кальция при сплавлении реагирует с углеродом с образованием сульфида кальция и угарного газа:

CaSO4 + 4C → CaS + 4CO

4. Многие средние сульфаты образуют устойчивые кристаллогидраты:

Na2SO4 ∙ 10H2O − глауберова соль

CaSO4 ∙ 2H2O − гипс

CuSO4 ∙ 5H2O − медный купорос

FeSO4 ∙ 7H2O − железный купорос

ZnSO4 ∙ 7H2O − цинковый купорос

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sulfur | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative name | sulphur (British spelling) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Allotropes | see Allotropes of sulfur | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | lemon yellow sintered microcrystals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(S) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sulfur in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 16 (chalcogens) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | p-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s2 3p4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 388.36 K (115.21 °C, 239.38 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 717.8 K (444.6 °C, 832.3 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | alpha: 2.07 g/cm3 beta: 1.96 g/cm3 gamma: 1.92 g/cm3 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 1.819 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 1314 K, 20.7 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | mono: 1.727 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | mono: 45 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 22.75 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, −1, 0, +1, +2, +3, +4, +5, +6 (a strongly acidic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 2.58 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 105±3 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 180 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Spectral lines of sulfur |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | orthorhombic

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 0.205 W/(m⋅K) (amorphous) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 2×1015 Ω⋅m (at 20 °C) (amorphous) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | (α) −15.5×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 7.7 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 2.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7704-34-9 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | before 2000 BCE[4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Recognized as an element by | Antoine Lavoisier (1777) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Isotopes of sulfur

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

34S abundances vary greatly (between 3.96 and 4.77 percent) in natural samples. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| references |

Sulfur (or sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula S8. Elemental sulfur is a bright yellow, crystalline solid at room temperature.

Sulfur is the tenth most abundant element by mass in the universe and the fifth most on Earth. Though sometimes found in pure, native form, sulfur on Earth usually occurs as sulfide and sulfate minerals. Being abundant in native form, sulfur was known in ancient times, being mentioned for its uses in ancient India, ancient Greece, China, and ancient Egypt. Historically and in literature sulfur is also called brimstone,[5] which means «burning stone».[6] Today, almost all elemental sulfur is produced as a byproduct of removing sulfur-containing contaminants from natural gas and petroleum.[7][8] The greatest commercial use of the element is the production of sulfuric acid for sulfate and phosphate fertilizers, and other chemical processes. Sulfur is used in matches, insecticides, and fungicides. Many sulfur compounds are odoriferous, and the smells of odorized natural gas, skunk scent, grapefruit, and garlic are due to organosulfur compounds. Hydrogen sulfide gives the characteristic odor to rotting eggs and other biological processes.

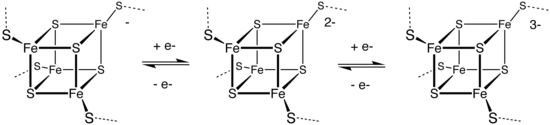

Sulfur is an essential element for all life, but almost always in the form of organosulfur compounds or metal sulfides. Amino acids (two proteinogenic: cysteine and methionine, and many other non-coded: cystine, taurine, etc.) and two vitamins (biotin and thiamine) are organosulfur compounds crucial for life. Many cofactors also contain sulfur, including glutathione, and iron–sulfur proteins. Disulfides, S–S bonds, confer mechanical strength and insolubility of the (among others) protein keratin, found in outer skin, hair, and feathers. Sulfur is one of the core chemical elements needed for biochemical functioning and is an elemental macronutrient for all living organisms.

Characteristics[edit]

As a solid, sulfur is a characteristic lemon yellow; when burned, sulfur melts into a blood-red liquid and emits a blue flame.

Physical properties[edit]

Sulfur forms several polyatomic molecules. The best-known allotrope is octasulfur, cyclo-S8. The point group of cyclo-S8 is D4d and its dipole moment is 0 D.[9] Octasulfur is a soft, bright-yellow solid that is odorless, but impure samples have an odor similar to that of matches.[10] It melts at 115.21 °C (239.38 °F), boils at 444.6 °C (832.3 °F)[5] and sublimes more or less between 20 °C (68 °F) and 50 °C (122 °F).[11] At 95.2 °C (203.4 °F), below its melting temperature, cyclo-octasulfur changes from α-octasulfur to the β-polymorph.[12] The structure of the S8 ring is virtually unchanged by this phase change, which affects the intermolecular interactions. Between its melting and boiling temperatures, octasulfur changes its allotrope again, turning from β-octasulfur to γ-sulfur, again accompanied by a lower density but increased viscosity due to the formation of polymers.[12] At higher temperatures, the viscosity decreases as depolymerization occurs. Molten sulfur assumes a dark red color above 200 °C (392 °F). The density of sulfur is about 2 g/cm3, depending on the allotrope; all of the stable allotropes are excellent electrical insulators.

Sulfur is insoluble in water but soluble in carbon disulfide and, to a lesser extent, in other nonpolar organic solvents, such as benzene and toluene.

Chemical properties[edit]

Under normal conditions, sulfur hydrolyzes very slowly to mainly form hydrogen sulfide and sulfuric acid:

- 1⁄2 S

8 + 4 H

2O → 3 H

2S + H

2SO

4

The reaction involves adsorption of protons onto S

8 clusters, followed by disproportionation into the reaction products.[13]

The second, fourth and sixth ionization energies of sulfur are 2252 kJ/mol−1, 4556 kJ/mol−1 and 8495.8 kJ/mol−1,respectively. A composition of products of sulfur’s reactions with oxidants (and its oxidation state) depends on that whether releasing out of a reaction energy overcomes these thresholds. Applying catalysts and / or supply of outer energy may vary sulfur’s oxidation state and a composition of reaction products. While reaction between sulfur and oxygen at normal conditions gives sulfur dioxide (oxidation state +4), formation of sulfur trioxide (oxidation state +6) requires temperature 400 – 600 °C and presence of a catalyst.

In reactions with elements of lesser electronegativity, it reacts as an oxidant and forms sulfides, where it has oxidation state –2.

Sulfur reacts with nearly all other elements with the exception of the noble gases, even with the notoriously unreactive metal iridium (yielding iridium disulfide).[14] Some of those reactions need elevated temperatures.[15]

Allotropes[edit]

The structure of the cyclooctasulfur molecule, S8

Sulfur forms over 30 solid allotropes, more than any other element.[16] Besides S8, several other rings are known.[17] Removing one atom from the crown gives S7, which is more of a deep yellow than the S8. HPLC analysis of «elemental sulfur» reveals an equilibrium mixture of mainly S8, but with S7 and small amounts of S6.[18] Larger rings have been prepared, including S12 and S18.[19][20]

Amorphous or «plastic» sulfur is produced by rapid cooling of molten sulfur—for example, by pouring it into cold water. X-ray crystallography studies show that the amorphous form may have a helical structure with eight atoms per turn. The long coiled polymeric molecules make the brownish substance elastic, and in bulk this form has the feel of crude rubber. This form is metastable at room temperature and gradually reverts to crystalline molecular allotrope, which is no longer elastic. This process happens within a matter of hours to days, but can be rapidly catalyzed.

Isotopes[edit]

Sulfur has 23 known isotopes, four of which are stable: 32S (94.99%±0.26%), 33S (0.75%±0.02%), 34S (4.25%±0.24%), and 36S (0.01%±0.01%).[21][22] Other than 35S, with a half-life of 87 days, the radioactive isotopes of sulfur have half-lives less than 3 hours.

The preponderance of sulfur-32 is explained by its production in the so-called alpha-process (one of the main classes of nuclear fusion reactions) in exploding stars. Other stable sulfur isotopes are produced in the bypass processes related with argon-34, and their composition depends on a type of a stellar explosion. For example, there is more sulfur-33 come from novae, than from supernovae.[23]

On the planet Earth the sulfur isotopic composition was determined by the Sun. Though it is assumed that the distribution of different sulfur isotopes should be more of less equal, it has been found that proportions of two most abundant sulfur isotopes sulfur-32 and sulfur-34 varies in different samples. Assaying of these isotopes ratio (δ34S) in the samples allows to make suggestions about their chemical history, and with support of other methods, it allows to age-date the samples, estimate temperature of equilibrium between ore and water, determine pH and oxygen fugacity, identify the activity of sulfate-reducing bacteria in the time of formation of the sample, or suggest the main sources of sulfur in ecosystems.[24] However, discussions about what is the real reason of the δ34S shifts, biological activity or postdeposital alteration, go on.[25]

For example, when sulfide minerals are precipitated, isotopic equilibration among solids and liquid may cause small differences in the δ34S values of co-genetic minerals. The differences between minerals can be used to estimate the temperature of equilibration. The δ13C and δ34S of coexisting carbonate minerals and sulfides can be used to determine the pH and oxygen fugacity of the ore-bearing fluid during ore formation.

In most forest ecosystems, sulfate is derived mostly from the atmosphere; weathering of ore minerals and evaporites contribute some sulfur. Sulfur with a distinctive isotopic composition has been used to identify pollution sources, and enriched sulfur has been added as a tracer in hydrologic studies. Differences in the natural abundances can be used in systems where there is sufficient variation in the 34S of ecosystem components. Rocky Mountain lakes thought to be dominated by atmospheric sources of sulfate have been found to have characteristic 34S values from lakes believed to be dominated by watershed sources of sulfate.

The radioactive sulfur-35 is formed in cosmic ray spallation of the atmospheric 40Ar. This fact may be used for proving the presence of recent (not more than 1 year) atmospheric sediments in various things. This isotope may be obtained artificially by different ways. In practice, a reaction 35Cl + n → 35S + p, that runs at irradiation potassium chloride by neutrons, is used.[26] The isotope sulfur-35 is used in various sulfur-containing compounds as a radioactive tracer for many biological studies, for example it was used in the Hershey-Chase experiment.

Working with the compounds containing this isotope is relatively safe, under condition of not falling those compounds inside an organism of an experimenter.[27]

Natural occurrence[edit]

Sulfur vat from which railroad cars are loaded, Freeport Sulphur Co., Hoskins Mound, Texas (1943)

Most of the yellow and orange hues of Io are due to elemental sulfur and sulfur compounds deposited by active volcanoes.

Sulfur extraction, East Java

A man carrying sulfur blocks from Kawah Ijen, a volcano in East Java, Indonesia, 2009

32S is created inside massive stars, at a depth where the temperature exceeds 2.5×109 K, by the fusion of one nucleus of silicon plus one nucleus of helium.[28] As this nuclear reaction is part of the alpha process that produces elements in abundance, sulfur is the 10th most common element in the universe.

Sulfur, usually as sulfide, is present in many types of meteorites. Ordinary chondrites contain on average 2.1% sulfur, and carbonaceous chondrites may contain as much as 6.6%. It is normally present as troilite (FeS), but there are exceptions, with carbonaceous chondrites containing free sulfur, sulfates and other sulfur compounds.[29] The distinctive colors of Jupiter’s volcanic moon Io are attributed to various forms of molten, solid, and gaseous sulfur.[30]

It is the fifth most common element by mass in the Earth. Elemental sulfur can be found near hot springs and volcanic regions in many parts of the world, especially along the Pacific Ring of Fire; such volcanic deposits are currently mined in Indonesia, Chile, and Japan. These deposits are polycrystalline, with the largest documented single crystal measuring 22×16×11 cm.[31] Historically, Sicily was a major source of sulfur in the Industrial Revolution.[32] Lakes of molten sulfur up to ~200 m in diameter have been found on the sea floor, associated with submarine volcanoes, at depths where the boiling point of water is higher than the melting point of sulfur.[33]

Native sulfur is synthesised by anaerobic bacteria acting on sulfate minerals such as gypsum in salt domes.[34][35] Significant deposits in salt domes occur along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, and in evaporites in eastern Europe and western Asia. Native sulfur may be produced by geological processes alone. Fossil-based sulfur deposits from salt domes were once the basis for commercial production in the United States, Russia, Turkmenistan, and Ukraine.[36] Currently, commercial production is still carried out in the Osiek mine in Poland. Such sources are now of secondary commercial importance, and most are no longer worked.

Common naturally occurring sulfur compounds include the sulfide minerals, such as pyrite (iron sulfide), cinnabar (mercury sulfide), galena (lead sulfide), sphalerite (zinc sulfide), and stibnite (antimony sulfide); and the sulfate minerals, such as gypsum (calcium sulfate), alunite (potassium aluminium sulfate), and barite (barium sulfate). On Earth, just as upon Jupiter’s moon Io, elemental sulfur occurs naturally in volcanic emissions, including emissions from hydrothermal vents.

The main industrial source of sulfur is now petroleum and natural gas.[7]

Compounds[edit]

Common oxidation states of sulfur range from −2 to +6. Sulfur forms stable compounds with all elements except the noble gases.

Electron transfer reactions[edit]

Sulfur polycations, S82+, S42+ and S162+ are produced when sulfur is reacted with oxidising agents in a strongly acidic solution.[37] The colored solutions produced by dissolving sulfur in oleum were first reported as early as 1804 by C.F. Bucholz, but the cause of the color and the structure of the polycations involved was only determined in the late 1960s. S82+ is deep blue, S42+ is yellow and S162+ is red.[12]

Reduction of sulfur gives various polysulfides with the formula Sx2-, many of which have been obtained crystalline form. Illustrative is the production of sodium tetrasulfide:

- 4 Na + S8 → 2 Na2S4

Some of these dianions dissociate to give radical anions, such as S3− gives the blue color of the rock lapis lazuli.

Two parallel sulfur chains grown inside a single-wall carbon nanotube (CNT, a). Zig-zag (b) and straight (c) S chains inside double-wall CNTs[38]

This reaction highlights a distinctive property of sulfur: its ability to catenate (bind to itself by formation of chains). Protonation of these polysulfide anions produces the polysulfanes, H2Sx where x= 2, 3, and 4.[39] Ultimately, reduction of sulfur produces sulfide salts:

- 16 Na + S8 → 8 Na2S

The interconversion of these species is exploited in the sodium–sulfur battery.

Hydrogenation[edit]

Treatment of sulfur with hydrogen gives hydrogen sulfide. When dissolved in water, hydrogen sulfide is mildly acidic:[5]

- H2S ⇌ HS− + H+

Hydrogen sulfide gas and the hydrosulfide anion are extremely toxic to mammals, due to their inhibition of the oxygen-carrying capacity of hemoglobin and certain cytochromes in a manner analogous to cyanide and azide (see below, under precautions).

Combustion[edit]

The two principal sulfur oxides are obtained by burning sulfur:

- S + O2 → SO2 (sulfur dioxide)

- 2 SO2 + O2 → 2 SO3 (sulfur trioxide)

Many other sulfur oxides are observed including the sulfur-rich oxides include sulfur monoxide, disulfur monoxide, disulfur dioxides, and higher oxides containing peroxo groups.

Halogenation[edit]

Sulfur reacts with fluorine to give the highly reactive sulfur tetrafluoride and the highly inert sulfur hexafluoride.[40] Whereas fluorine gives S(IV) and S(VI) compounds, chlorine gives S(II) and S(I) derivatives. Thus, sulfur dichloride, disulfur dichloride, and higher chlorosulfanes arise from the chlorination of sulfur. Sulfuryl chloride and chlorosulfuric acid are derivatives of sulfuric acid; thionyl chloride (SOCl2) is a common reagent in organic synthesis.[41]

Pseudohalides[edit]

Sulfur oxidizes cyanide and sulfite to give thiocyanate and thiosulfate, respectively.

Metal sulfides[edit]

Sulfur reacts with many metals. Electropositive metals give polysulfide salts. Copper, zinc, silver are attacked by sulfur, see tarnishing. Although many metal sulfides are known, most are prepared by high temperature reactions of the elements.[42]

Organic compounds[edit]

- Illustrative organosulfur compounds

-

Allicin, a chemical compound in garlic

-

-

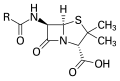

Penicillin, an antibiotic where «R» is the variable group

Some of the main classes of sulfur-containing organic compounds include the following:[43]

- Thiols or mercaptans (so called because they capture mercury as chelators) are the sulfur analogs of alcohols; treatment of thiols with base gives thiolate ions.

- Thioethers are the sulfur analogs of ethers.

- Sulfonium ions have three groups attached to a cationic sulfur center. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) is one such compound, important in the marine organic sulfur cycle.

- Sulfoxides and sulfones are thioethers with one and two oxygen atoms attached to the sulfur atom, respectively. The simplest sulfoxide, dimethyl sulfoxide, is a common solvent; a common sulfone is sulfolane.

- Sulfonic acids are used in many detergents.

Compounds with carbon–sulfur multiple bonds are uncommon, an exception being carbon disulfide, a volatile colorless liquid that is structurally similar to carbon dioxide. It is used as a reagent to make the polymer rayon and many organosulfur compounds. Unlike carbon monoxide, carbon monosulfide is stable only as an extremely dilute gas, found between solar systems.[44]

Organosulfur compounds are responsible for some of the unpleasant odors of decaying organic matter. They are widely known as the odorant in domestic natural gas, garlic odor, and skunk spray. Not all organic sulfur compounds smell unpleasant at all concentrations: the sulfur-containing monoterpenoid (grapefruit mercaptan) in small concentrations is the characteristic scent of grapefruit, but has a generic thiol odor at larger concentrations. Sulfur mustard, a potent vesicant, was used in World War I as a disabling agent.[45]

Sulfur–sulfur bonds are a structural component used to stiffen rubber, similar to the disulfide bridges that rigidify proteins (see biological below). In the most common type of industrial «curing» or hardening and strengthening of natural rubber, elemental sulfur is heated with the rubber to the point that chemical reactions form disulfide bridges between isoprene units of the polymer. This process, patented in 1843, made rubber a major industrial product, especially in automobile tires. Because of the heat and sulfur, the process was named vulcanization, after the Roman god of the forge and volcanism.

History[edit]

Antiquity[edit]

Being abundantly available in native form, sulfur was known in ancient times and is referred to in the Torah (Genesis). English translations of the Christian Bible commonly referred to burning sulfur as «brimstone», giving rise to the term «fire-and-brimstone» sermons, in which listeners are reminded of the fate of eternal damnation that await the unbelieving and unrepentant. It is from this part of the Bible[46] that Hell is implied to «smell of sulfur» (likely due to its association with volcanic activity). According to the Ebers Papyrus, a sulfur ointment was used in ancient Egypt to treat granular eyelids. Sulfur was used for fumigation in preclassical Greece;[47] this is mentioned in the Odyssey.[48] Pliny the Elder discusses sulfur in book 35 of his Natural History, saying that its best-known source is the island of Melos. He mentions its use for fumigation, medicine, and bleaching cloth.[49]

A natural form of sulfur known as shiliuhuang (石硫黄) was known in China since the 6th century BC and found in Hanzhong.[50] By the 3rd century, the Chinese had discovered that sulfur could be extracted from pyrite.[50] Chinese Daoists were interested in sulfur’s flammability and its reactivity with certain metals, yet its earliest practical uses were found in traditional Chinese medicine.[50] A Song dynasty military treatise of 1044 AD described various formulas for Chinese black powder, which is a mixture of potassium nitrate (KNO

3), charcoal, and sulfur. It remains an ingredient of black gunpowder.

Sulphur

Brimstone

Alchemical signs for sulfur, or the combustible elements, and brimstone, an older/archaic name for sulfur.[51]

Indian alchemists, practitioners of the «science of chemicals» (Sanskrit: रसशास्त्र, romanized: rasaśāstra), wrote extensively about the use of sulfur in alchemical operations with mercury, from the eighth century AD onwards.[52] In the rasaśāstra tradition, sulfur is called «the smelly» (गन्धक, gandhaka).

Early European alchemists gave sulfur a unique alchemical symbol, a triangle atop a cross (🜍). (This is sometimes confused with the astronomical crossed-spear symbol ⚴ for 2 Pallas.) The variation known as brimstone has a symbol combining a two-barred cross atop a lemniscate (🜏). In traditional skin treatment, elemental sulfur was used (mainly in creams) to alleviate such conditions as scabies, ringworm, psoriasis, eczema, and acne. The mechanism of action is unknown—though elemental sulfur does oxidize slowly to sulfurous acid, which is (through the action of sulfite) a mild reducing and antibacterial agent.[53][54][55]

Modern times[edit]

Above: Sicilian kiln used to obtain sulfur from volcanic rock (diagram from a 1906 chemistry book)

Right: Today sulfur is known to have antifungal, antibacterial, and keratolytic activity; in the past it was used against acne vulgaris, rosacea, seborrheic dermatitis, dandruff, pityriasis versicolor, scabies, and warts.[56] This 1881 advertisement baselessly claims efficacy against rheumatism, gout, baldness, and graying of hair.

Sulfur appears in a column of fixed (non-acidic) alkali in a chemical table of 1718.[57] Antoine Lavoisier used sulfur in combustion experiments, writing of some of these in 1777.[58]

Sulfur deposits in Sicily were the dominant source for more than a century. By the late 18th century, about 2,000 tonnes per year of sulfur were imported into Marseille, France, for the production of sulfuric acid for use in the Leblanc process. In industrializing Britain, with the repeal of tariffs on salt in 1824, demand for sulfur from Sicily surged upward. The increasing British control and exploitation of the mining, refining, and transportation of the sulfur, coupled with the failure of this lucrative export to transform Sicily’s backward and impoverished economy, led to the Sulfur Crisis of 1840, when King Ferdinand II gave a monopoly of the sulfur industry to a French firm, violating an earlier 1816 trade agreement with Britain. A peaceful solution was eventually negotiated by France.[59][60]

In 1867, elemental sulfur was discovered in underground deposits in Louisiana and Texas. The highly successful Frasch process was developed to extract this resource.[61]

In the late 18th century, furniture makers used molten sulfur to produce decorative inlays.[62] Molten sulfur is sometimes still used for setting steel bolts into drilled concrete holes where high shock resistance is desired for floor-mounted equipment attachment points. Pure powdered sulfur was used as a medicinal tonic and laxative.[36]

With the advent of the contact process, the majority of sulfur today is used to make sulfuric acid for a wide range of uses, particularly fertilizer.[63]

In recent times, the main source of sulfur has become petroleum and natural gas. This is due to the requirement to remove sulfur from fuels in order to prevent acid rain, and has resulted in a surplus of sulfur.[7]

Spelling and etymology[edit]

Sulfur is derived from the Latin word sulpur, which was Hellenized to sulphur in the erroneous belief that the Latin word came from Greek. This spelling was later reinterpreted as representing an /f/ sound and resulted in the spelling sulfur, which appears in Latin toward the end of the Classical period. The true Ancient Greek word for sulfur, θεῖον, theîon (from earlier θέειον, théeion), is the source of the international chemical prefix thio-. The Modern Standard Greek word for sulfur is θείο, theío.

In 12th-century Anglo-French, it was sulfre. In the 14th century, the erroneously Hellenized Latin -ph- was restored in Middle English sulphre. By the 15th century, both full Latin spelling variants sulfur and sulphur became common in English. The parallel f~ph spellings continued in Britain until the 19th century, when the word was standardized as sulphur.[64] On the other hand, sulfur was the form chosen in the United States, whereas Canada uses both.

The IUPAC adopted the spelling sulfur in 1990 or 1971, depending on the source cited,[65] as did the Nomenclature Committee of the Royal Society of Chemistry in 1992, restoring the spelling sulfur to Britain.[66] Oxford Dictionaries note that «in chemistry and other technical uses … the -f- spelling is now the standard form for this and related words in British as well as US contexts, and is increasingly used in general contexts as well.»[67]

Production[edit]

Traditional sulfur mining at Ijen Volcano, East Java, Indonesia. This image shows the dangerous and rugged conditions the miners face, including toxic smoke and high drops, as well as their lack of protective equipment. The pipes over which they are standing are for condensing sulfur vapors.

Sulfur may be found by itself and historically was usually obtained in this form; pyrite has also been a source of sulfur.[68] In volcanic regions in Sicily, in ancient times, it was found on the surface of the Earth, and the «Sicilian process» was used: sulfur deposits were piled and stacked in brick kilns built on sloping hillsides, with airspaces between them. Then, some sulfur was pulverized, spread over the stacked ore and ignited, causing the free sulfur to melt down the hills. Eventually the surface-borne deposits played out, and miners excavated veins that ultimately dotted the Sicilian landscape with labyrinthine mines. Mining was unmechanized and labor-intensive, with pickmen freeing the ore from the rock, and mine-boys or carusi carrying baskets of ore to the surface, often through a mile or more of tunnels. Once the ore was at the surface, it was reduced and extracted in smelting ovens. The conditions in Sicilian sulfur mines were horrific, prompting Booker T. Washington to write «I am not prepared just now to say to what extent I believe in a physical hell in the next world, but a sulphur mine in Sicily is about the nearest thing to hell that I expect to see in this life.»[69]

Elemental sulfur was extracted from salt domes (in which it sometimes occurs in nearly pure form) until the late 20th century. Sulfur is now produced as a side product of other industrial processes such as in oil refining, in which sulfur is undesired. As a mineral, native sulfur under salt domes is thought to be a fossil mineral resource, produced by the action of anaerobic bacteria on sulfate deposits. It was removed from such salt-dome mines mainly by the Frasch process.[36] In this method, superheated water was pumped into a native sulfur deposit to melt the sulfur, and then compressed air returned the 99.5% pure melted product to the surface. Throughout the 20th century this procedure produced elemental sulfur that required no further purification. Due to a limited number of such sulfur deposits and the high cost of working them, this process for mining sulfur has not been employed in a major way anywhere in the world since 2002.[70][71]

Today, sulfur is produced from petroleum, natural gas, and related fossil resources, from which it is obtained mainly as hydrogen sulfide.[7] Organosulfur compounds, undesirable impurities in petroleum, may be upgraded by subjecting them to hydrodesulfurization, which cleaves the C–S bonds:[70][71]

- R-S-R + 2 H2 → 2 RH + H2S

The resulting hydrogen sulfide from this process, and also as it occurs in natural gas, is converted into elemental sulfur by the Claus process. This process entails oxidation of some hydrogen sulfide to sulfur dioxide and then the comproportionation of the two:[70][71]

- 3 O2 + 2 H2S → 2 SO2 + 2 H2O

- SO2 + 2 H2S → 3 S + 2 H2O

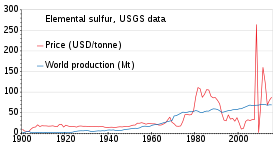

Production and price (US market) of elemental sulfur

Owing to the high sulfur content of the Athabasca Oil Sands, stockpiles of elemental sulfur from this process now exist throughout Alberta, Canada.[72] Another way of storing sulfur is as a binder for concrete, the resulting product having many desirable properties (see sulfur concrete).[73]

Sulfur is still mined from surface deposits in poorer nations with volcanoes, such as Indonesia, and worker conditions have not improved much since Booker T. Washington’s days.[74]

The world production of sulfur in 2011 amounted to 69 million tonnes (Mt), with more than 15 countries contributing more than 1 Mt each. Countries producing more than 5 Mt are China (9.6), the United States (8.8), Canada (7.1) and Russia (7.1).[75] Production has been slowly increasing from 1900 to 2010; the price was unstable in the 1980s and around 2010.[76]

Applications[edit]

Sulfuric acid[edit]

Elemental sulfur is used mainly as a precursor to other chemicals. Approximately 85% (1989) is converted to sulfuric acid (H2SO4):

- 1⁄8 S8 + 3⁄2 O2 + H2O → H2SO4

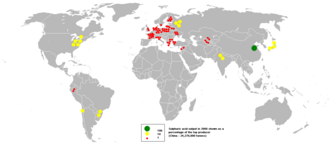

Sulfuric acid production in 2000

In 2010, the United States produced more sulfuric acid than any other inorganic industrial chemical.[76] The principal use for the acid is the extraction of phosphate ores for the production of fertilizer manufacturing. Other applications of sulfuric acid include oil refining, wastewater processing, and mineral extraction.[36]

Other important sulfur chemistry[edit]

Sulfur reacts directly with methane to give carbon disulfide, which is used to manufacture cellophane and rayon.[36] One of the uses of elemental sulfur is in vulcanization of rubber, where polysulfide chains crosslink organic polymers. Large quantities of sulfites are used to bleach paper and to preserve dried fruit. Many surfactants and detergents (e.g. sodium lauryl sulfate) are sulfate derivatives. Calcium sulfate, gypsum, (CaSO4·2H2O) is mined on the scale of 100 million tonnes each year for use in Portland cement and fertilizers.

When silver-based photography was widespread, sodium and ammonium thiosulfate were widely used as «fixing agents». Sulfur is a component of gunpowder («black powder»).

Fertilizer[edit]

Amino acids synthesized by living organisms such as methionine and cysteine contain organosulfur groups (thioester and thiol respectively). The antioxidant glutathione protecting many living organisms against free radicals and oxidative stress also contains organic sulfur. Some crops such as onion and garlic also produce different organosulfur compounds such as syn-propanethial-S-oxide responsible of lacrymal irritation (onions), or diallyl disulfide and allicin (garlic). Sulfates, commonly found in soils and groundwaters are often a sufficient natural source of sulfur for plants and bacteria. Atmospheric deposition of sulfur dioxide (SO2) is also a common artificial source (coal combustion) of sulfur for the soils. Under normal circumstances, in most agricultural soils, sulfur is not a limiting nutrient for plants and microorganisms (see the Liebig’s law of the minimum#Liebig’s barrel). However, in some circumstance, soils can be depleted in sulfate, e.g. if this later is leached by meteoric water (rain) or if the requirements in sulfur for some types of crops are high. This explains that sulfur is increasingly recognized and used as a component of fertilizers. The most important form of sulfur for fertilizer is the calcium sulfate, commonly found in nature as the mineral gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O). Elemental sulfur is hydrophobic (not soluble in water) and cannot be used directly by plants. Elemental sulfur (ES) is sometimes mixed with bentonite to amend depleted soils for crops with high requirement in organo-sulfur. Over time, oxidation abiotic processes with atmospheric oxygen and soil bacteria can oxidize and convert elemental sulfur to soluble derivatives, which can then be used by microorganisms and plants. Sulfur improves the efficiency of other essential plant nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus.[77] Biologically produced sulfur particles are naturally hydrophilic due to a biopolymer coating and are easier to disperse over the land in a spray of diluted slurry, resulting in a faster uptake by plants.

The plants requirement for sulfur equals or exceeds the requirement for phosphorus. It is an essential nutrient for plant growth, root nodule formation of legumes, and immunity and defense systems. Sulfur deficiency has become widespread in many countries in Europe.[78][79][80] Because atmospheric inputs of sulfur continue to decrease, the deficit in the sulfur input/output is likely to increase unless sulfur fertilizers are used. Atmospheric inputs of sulfur decrease because of actions taken to limit acid rains.[81][77]

Fungicide and pesticide[edit]

Sulfur candle originally sold for home fumigation

Elemental sulfur is one of the oldest fungicides and pesticides. «Dusting sulfur», elemental sulfur in powdered form, is a common fungicide for grapes, strawberry, many vegetables and several other crops. It has a good efficacy against a wide range of powdery mildew diseases as well as black spot. In organic production, sulfur is the most important fungicide. It is the only fungicide used in organically farmed apple production against the main disease apple scab under colder conditions. Biosulfur (biologically produced elemental sulfur with hydrophilic characteristics) can also be used for these applications.

Standard-formulation dusting sulfur is applied to crops with a sulfur duster or from a dusting plane. Wettable sulfur is the commercial name for dusting sulfur formulated with additional ingredients to make it water miscible.[73][82] It has similar applications and is used as a fungicide against mildew and other mold-related problems with plants and soil.

Elemental sulfur powder is used as an «organic» (i.e., «green») insecticide (actually an acaricide) against ticks and mites. A common method of application is dusting the clothing or limbs with sulfur powder.

A diluted solution of lime sulfur (made by combining calcium hydroxide with elemental sulfur in water) is used as a dip for pets to destroy ringworm (fungus), mange, and other dermatoses and parasites.

Sulfur candles of almost pure sulfur were burned to fumigate structures and wine barrels, but are now considered too toxic for residences.

Pharmaceuticals[edit]

Sulfur (specifically octasulfur, S8) is used in pharmaceutical skin preparations for the treatment of acne and other conditions. It acts as a keratolytic agent and also kills bacteria, fungi, scabies mites, and other parasites.[83] Precipitated sulfur and colloidal sulfur are used, in form of lotions, creams, powders, soaps, and bath additives, for the treatment of acne vulgaris, acne rosacea, and seborrhoeic dermatitis.[84]

Many drugs contain sulfur. Early examples include antibacterial sulfonamides, known as sulfa drugs. A more recent example is mucolytic acetylcysteine. Sulfur is a part of many bacterial defense molecules. Most β-lactam antibiotics, including the penicillins, cephalosporins and monobactams contain sulfur.[43]

Batteries[edit]

Due to their high energy density and the availability of sulfur, there is ongoing research in creating rechargeable lithium-sulfur batteries. Until now, carbonate electrolytes have caused failures in such batteries after a single cycle. In February 2022, researchers at Drexel University have not only created a prototypical battery that lasted 4000 recharge cycles, but also found the first monoclinic gamma sulfur that remained stable below 95 degrees Celsius.[85]

Biological role[edit]

Sulfur is an essential component of all living cells. It is the eighth most abundant element in the human body by weight,[86] about equal in abundance to potassium, and slightly greater than sodium and chlorine.[87] A 70 kg (150 lb) human body contains about 140 grams of sulfur.[88] The main dietary source of sulfur for humans is sulfur-containing amino-acids,[89] which can be found in plant and animal proteins.[90]

Transferring sulfur between inorganic and biomolecules[edit]

In the 1880s, while studying Beggiatoa (a bacterium living in a sulfur rich environment), Sergei Winogradsky found that it oxidized hydrogen sulfide (H2S) as an energy source, forming intracellular sulfur droplets. Winogradsky referred to this form of metabolism as inorgoxidation (oxidation of inorganic compounds).[91] Another contributor, who continued to study it was Selman Waksman.[92] Primitive bacteria that live around deep ocean volcanic vents oxidize hydrogen sulfide for their nutrition, as discovered by Robert Ballard.[8]

Sulfur oxidizers can use as energy sources reduced sulfur compounds, including hydrogen sulfide, elemental sulfur, sulfite, thiosulfate, and various polythionates (e.g., tetrathionate).[93] They depend on enzymes such as sulfur oxygenase and sulfite oxidase to oxidize sulfur to sulfate. Some lithotrophs can even use the energy contained in sulfur compounds to produce sugars, a process known as chemosynthesis. Some bacteria and archaea use hydrogen sulfide in place of water as the electron donor in chemosynthesis, a process similar to photosynthesis that produces sugars and uses oxygen as the electron acceptor. Sulfur-based chemosynthesis may be simplifiedly compared with photosynthesis:

- H2S + CO2 → sugars + S

- H2O + CO2 → sugars + O2

There are bacteria combining these two ways of nutrition: green sulfur bacteria and purple sulfur bacteria.[94] Also sulfur-oxidizing bacteria can go into symbiosis with larger organisms, enabling the later to use hydrogen sulfide as food to be oxidized. Example: the giant tube worm.[95]

There are sulfate-reducing bacteria, that, by contrast, «breathe sulfate» instead of oxygen. They use organic compounds or molecular hydrogen as the energy source. They use sulfur as the electron acceptor, and reduce various oxidized sulfur compounds back into sulfide, often into hydrogen sulfide. They can grow on other partially oxidized sulfur compounds (e.g. thiosulfates, thionates, polysulfides, sulfites).

There are studies pointing that many deposits of native sulfur in places that were the bottom of the ancient oceans have biological origin.[96][97][98] These studies indicate that this native sulfur have been obtained through biological activity, but what is responsible for that (sulfur-oxidizing bacteria or sulfate-reducing bacteria) is still unknown for sure.

Sulfur is absorbed by plants roots from soil as sulfate and transported as a phosphate ester. Sulfate is reduced to sulfide via sulfite before it is incorporated into cysteine and other organosulfur compounds.[99]

- SO42− → SO32− → H2S → cysteine (thiol) → methionine (thioether)

While the plants’ role in transferring sulfur to animals by food chains is more or less understood, the role of sulfur bacteria is just getting investigated.[100][101]

Protein and organic metabolites[edit]

In all forms of life, most of the sulfur is contained in two proteinogenic amino acids (cysteine and methionine), thus the element is present in all proteins that contain these amino acids, as well as in respective peptides.[102] Some of the sulfur is comprised in certain metabolites — many of which are cofactors, — and sulfated polysaccharides of connective tissue (chondroitin sulfates, heparin).

Schematic representation of disulfide bridges (in yellow) between two protein helices

Proteins, to execute their biological function, need to have specific space geometry. Formation of this geometry is performed in a process called protein folding, and is provided by intra- and inter-molecular bonds. The process has several stages. While at premier stages a polypeptide chain folds due to hydrogen bonds, at later stages folding is provided (apart from hydrogen bonds) by covalent bonds between two sulfur atoms of two cysteine residues (so called disulfide bridges) at different places of a chain (tertriary protein structure) as well as between two cysteine residues in two separated protein subunits (quaternary protein structure). Both structures easily may be seen in insulin. As the bond energy of a covalent disulfide bridge is higher than the energy of a coordinate bond or hydrophylic either hydrophobic interaction, the higher disulfide bridges content leads the higher energy needed for protein denaturation. In general disulfide bonds are necessary in proteins functioning outside cellular space, and they do not change proteins’ conformation (geometry), but serve as its stabilizers.[103] Within cytoplasm cysteine residues of proteins are saved in reduced state (i.e. in -SH form) by thioredoxins.[104]

This property manifests in following examples. Lysozyme is stable enough to be applied as a drug.[105] Feathers and hair have relative strength, and consisting in them keratin is considered indigestible by most organisms. However, there are fungi and bacteria containing keratinase, and are able to destruct keratin.

Many important cellular enzymes use prosthetic groups ending with -SH moieties to handle reactions involving acyl-containing biochemicals: two common examples from basic metabolism are coenzyme A and alpha-lipoic acid.[106] Cysteine-related metabolites homocysteine and taurine are other sulfur-containing amino acids that are similar in structure, but not coded by DNA, and are not part of the primary structure of proteins, take part in various locations of mammalian physiology.[107][108] Two of the 13 classical vitamins, biotin and thiamine, contain sulfur, and serve as cofactors to several enzymes.[109][110]

In intracellular chemistry, sulfur operates as a carrier of reducing hydrogen and its electrons for cellular repair of oxidation. Reduced glutathione, a sulfur-containing tripeptide, is a reducing agent through its sulfhydryl (-SH) moiety derived from cysteine.