Перевод «шри-ланка» на английский

Ваш текст переведен частично.

Вы можете переводить не более 999 символов за один раз.

Войдите или зарегистрируйтесь бесплатно на PROMT.One и переводите еще больше!

<>

Контексты

Коломбо, Шри-Ланка — медицинские травы.

Colombo, Sri Lanka — Medicinal Herbs.

Шри-Ланка – это как раз такой случай.

Sri Lanka is a case in point.

Бакалавр естественных наук, Университет Перадении, Шри-Ланка.

Bachelor of Science, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka.

Могло бы правительство Шри-Ланка воспользоваться опытом Малайи?

Could Sri Lanka have learned anything from the Malayan experience?

Малайя и Шри-Ланка: общинная политика или межобщинная война?

Malaya and Sri Lanka: Communal Politics or Communal War?

Бесплатный переводчик онлайн с русского на английский

Вам нужно переводить на английский сообщения в чатах, письма бизнес-партнерам и в службы поддержки онлайн-магазинов или домашнее задание? PROMT.One мгновенно переведет с русского на английский и еще на 20+ языков.

Точный переводчик

С помощью PROMT.One наслаждайтесь точным переводом с русского на английский, а также смотрите английскую транскрипцию, произношение и варианты переводов слов с примерами употребления в предложениях. Бесплатный онлайн-переводчик PROMT.One — достойная альтернатива Google Translate и другим сервисам, предоставляющим перевод с английского на русский и с русского на английский. Переводите в браузере на персональных компьютерах, ноутбуках, на мобильных устройствах или установите мобильное приложение Переводчик PROMT.One для iOS и Android.

Нужно больше языков?

PROMT.One бесплатно переводит онлайн с русского на азербайджанский, арабский, греческий, иврит, испанский, итальянский, казахский, китайский, корейский, немецкий, португальский, татарский, турецкий, туркменский, узбекский, украинский, финский, французский, эстонский и японский.

шри-ланка

-

1

шри ланка

Sokrat personal > шри ланка

-

2

Шри-Ланка

2) Geography: Ceylon, Ceylon , Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Шри-Ланка

-

3

Шри-Ланка

Русско-английский географический словарь > Шри-Ланка

-

4

Шри-Ланка

Banks. Exchanges. Accounting. (Russian-English) > Шри-Ланка

-

5

Шри-Ланка

Русско-Английский новый экономический словарь > Шри-Ланка

-

6

Шри-Ланка

Новый русско-английский словарь > Шри-Ланка

-

7

Шри-Ланка

Новый большой русско-английский словарь > Шри-Ланка

-

8

Шри-Ланка

Sri Lanka [‘sri’læŋkə], Democratic Socialist Republic of

Американизмы. Русско-английский словарь. > Шри-Ланка

-

9

Шри-Ланка

Русско-английский синонимический словарь > Шри-Ланка

-

10

шри ланка

Русско-английский большой базовый словарь > шри ланка

-

11

Демократическая Социалистическая Республика Шри-Ланка

Русско-английский географический словарь > Демократическая Социалистическая Республика Шри-Ланка

-

12

(о.) Шри-Ланка

Geography:Ceylon , Sri Lanka

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > (о.) Шри-Ланка

-

13

Демократическая Социалистическая Республика Шри-Ланка

Geography: Ceylon , Sri Lanka , (the) Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > Демократическая Социалистическая Республика Шри-Ланка

-

14

(гос-во) Шри-Ланка

Универсальный русско-английский словарь > (гос-во) Шри-Ланка

-

15

Шри-Джаяварденепура-Котте

Sri Jayewardenepura Kotte

Русско-английский географический словарь > Шри-Джаяварденепура-Котте

-

16

Амбалантота

Русско-английский географический словарь > Амбалантота

-

17

Анурадхапура

Русско-английский географический словарь > Анурадхапура

-

18

Бадулла

Русско-английский географический словарь > Бадулла

-

19

Батикалоа

Русско-английский географический словарь > Батикалоа

-

20

Вавуния

Русско-английский географический словарь > Вавуния

Страницы

- Следующая →

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

См. также в других словарях:

-

Шри-Ланка — Демократическая Социалистическая Республика Шри Ланка, гос во в Юж. Азии, на о. Шри Ланка. Название от санскр. шри славный, великолепный, благословенный , ланка земля . До 1972 г. называлось Цейлон. В основе этого названия санскр. Синхала двипа… … Географическая энциклопедия

-

Шри-Ланка — Демократическая Социалистическая Республика Шри Ланка (до 1972 Цейлон), государство в Южной Азии, на острове Шри Ланка в Индийском океане, у южной оконечности полуострова Индостан. 65,6 тыс. км2. Население свыше 18,3 млн. человек (1996), в… … Энциклопедический словарь

-

Шри-Ланка — Шри Ланка. Древний город Анурадхапура. ШРИ ЛАНКА (Демократическая Социалистическая Республика Шри Ланка), государство в Южной Азии, на острове Шри Ланка в Индийском океане, у южной оконечности полуострова Индостан. Площадь 65,6 тыс. км2.… … Иллюстрированный энциклопедический словарь

-

Шри-Ланка — – страна абсолютной экзотики именно так можно назвать небольшой остров, расположенный в Индийском океане. Из всемирных исторических… … Города мира

-

ШРИ-ЛАНКА — Демократическая Социалистическая Республика Шри Ланка (до 1972 Цейлон), государство в Юж. Азии, на о. Шри Ланка в Индийском ок., у южной оконечности п ова Индостан. 65,6 тыс. км². население св. 17,6 млн. человек (1993), в основном сингалы… … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

-

ШРИ-ЛАНКА — (до 1972 Цейлон), Демократическая Социалистическая Республика Шри Ланка, гос во в Юж. Азии, на о. Шри Ланка, в Индийском ок. Пл. 66 тыс. км2. Нас. 15,4 млн. ч. (1983). Столица Коломбо (586 т. ж., 1981). Ш. Л. до 1948 колония, до 1972 доминион… … Демографический энциклопедический словарь

-

Шри-Ланка — Республика Шри Ланка, государство на одноименном острове (бывший Цейлон) в Индийском океане, у южной оконечности полуострова Индостан. Художественная культура Шри Ланки восходит к палеолиту и неолиту (дольмены, жертвенники, наскальные… … Художественная энциклопедия

-

шри-ланка — Цейлон, изумрудный остров Словарь русских синонимов. шри ланка сущ., кол во синонимов: 4 • изумрудный остров (1) • … Словарь синонимов

-

Шри-Ланка — (Sri Lanka), быв. Цейлон, гос во в Юж. Азии на о. Шри Ланка в Индийском океане у юж. оконечности п ова Индостан. В ранний период истории находилось под сильным инд. влиянием, пережило три фазы европ. колонизации. Преобладающая на о ве сингальская … Всемирная история

-

ШРИ-ЛАНКА — Территория 65,6 тыс.кв.км, население 16 млн. человек (1986). Это в основном аграрная страна. Главная отрасль сельского хозяйства производство чая, продовольственная культура рис. Животноводство развито слабо. Крупный рогатый скот используют в ка … Мировое овцеводство

-

Шри-Ланка — (до 1972 Цейлон) Республика Шри Ланка, государство на одноимённом острове в Индийском океане, к Ю. В. от полуострова Индостан. Входит в Содружество (брит.). Площадь 65,6 тыс. км2. Население 13,7 млн. чел. (1976). Столица г. Коломбо. В… … Большая советская энциклопедия

Coordinates: 7°N 81°E / 7°N 81°E

Sri Lanka (, ; Sinhala: ශ්රී ලංකා, romanized: Śrī Laṅkā (IPA: [ʃriː laŋkaː]); Tamil: இலங்கை, romanized: Ilaṅkai (IPA: [ilaŋɡaj])), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian peninsula by the Gulf of Mannar and the Palk Strait. Sri Lanka shares a maritime border with the Maldives in the south-west and India in the north-west.

|

Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Flag Emblem |

||||

| Anthem: «Sri Lanka Matha» (English: «Mother Sri Lanka») |

||||

|

||||

| Capital |

|

|||

| Largest city | Colombo | |||

| Official languages |

|

|||

| Recognised languages | English | |||

| Ethnic groups

(2012[4]) |

|

|||

| Religion

(2012) |

70.2% Buddhism (official)[5] 12.6% Hinduism 9.7% Islam 7.4% Christianity 0.1% Other/None |

|||

| Demonym(s) | Sri Lankan | |||

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic[6] | |||

|

• President |

Ranil Wickremesinghe | |||

|

• Prime Minister |

Dinesh Gunawardena | |||

|

• Speaker of the Parliament |

Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena | |||

|

• Chief Justice |

Jayantha Jayasuriya | |||

| Legislature | Parliament | |||

| Formation | ||||

|

• Kingdom established[7] |

543 BCE | |||

|

• Rajarata established[8] |

437 BCE | |||

|

• Kandyan Wars |

1796 | |||

|

• Kandyan Convention signed |

1815 | |||

|

• Independence |

4 February 1948 | |||

|

• Republic |

22 May 1972 | |||

|

• Current constitution |

7 September 1978 | |||

| Area | ||||

|

• Total |

65,610 km2 (25,330 sq mi) (120th) | |||

|

• Water (%) |

4.4 | |||

| Population | ||||

|

• 2020 estimate |

||||

|

• 2012 census |

20,277,597[10] | |||

|

• Density |

337.7/km2 (874.6/sq mi) (24th) | |||

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate | |||

|

• Total |

||||

|

• Per capita |

||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate | |||

|

• Total |

||||

|

• Per capita |

||||

| Gini (2016) | 39.8[12] medium |

|||

| HDI (2021) | high · 73rd |

|||

| Currency | Sri Lankan rupee (Rs) (LKR) | |||

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (SLST) | |||

| Date format |

|

|||

| Driving side | left | |||

| Calling code | +94 | |||

| ISO 3166 code | LK | |||

| Internet TLD |

|

|||

|

Website |

Sri Lanka has a population of around 22 million (2020) and is home to many cultures, languages, and ethnicities. The Sinhalese people form the majority of the nation’s population, followed by the Tamils, who are the largest minority group and are concentrated in northern Sri Lanka; both the linguistic groups have played an influential role in the island’s history. Other long established groups include the Moors, the Burghers, the Malays, the Chinese, and the indigenous Vedda.[14]

Sri Lanka’s documented history goes back 3,000 years, with evidence of prehistoric human settlements that dates back at least 125,000 years.[15] The earliest known Buddhist writings of Sri Lanka, known collectively as the Pāli canon, date to the fourth Buddhist council, which took place in 29 BCE.[16][17] Also called the Teardrop of India, or the Granary of the East, Sri Lanka’s geographic location and deep harbours have made it of great strategic importance, from the earliest days of the ancient Silk Road trade route to today’s so-called maritime Silk Road.[18][19][20] Because its location made it a major trading hub, it was already known to both Far Easterners and Europeans as long ago as the Anuradhapura period (377 BCE–1017 CE). During a period of great political crisis in the Kingdom of Kotte, the Portuguese arrived in Sri Lanka and sought to control the island’s maritime trade, with a part of Sri Lanka subsequently becoming a Portuguese possession. After the Sinhalese-Portuguese war, the Dutch and the Kingdom of Kandy took control of those areas. The Dutch possessions were then taken by the British, who later extended their control over the whole island, colonising it from 1815 to 1948. A national movement for political independence arose in the early 20th century, and in 1948, Ceylon became a dominion. The dominion was succeeded by the republic named Sri Lanka in 1972. Sri Lanka’s more recent history was marred by a 26-year civil war, which began in 1983 and ended decisively in 2009, when the Sri Lanka Armed Forces defeated the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.[21]

Sri Lanka is a developing country, ranking 73rd on the Human Development Index. It is the highest-ranked South Asian nation in terms of development and has the second-highest per capita income in South Asia; however, the ongoing economic crisis has resulted in the collapse of the currency, rising inflation, and a humanitarian crisis due to a severe shortage of essentials. It has also led to an eruption of street protests, with citizens successfully demanding that the president and the government step down.[22] The island has had a long history of engagement with modern international groups: it is a founding member of the SAARC and a member of the United Nations, the Commonwealth of Nations, the G77, and the Non-Aligned Movement.

Toponymy

In antiquity, Sri Lanka was known to travellers by a variety of names. According to the Mahāvaṃsa, the legendary Prince Vijaya named the island Tambapaṇṇĩ («copper-red hands» or «copper-red earth»), because his followers’ hands were reddened by the red soil of the area where he landed.[23][24] In Hindu mythology, the term Lankā («Island») appears but it is unknown whether it refers to the modern day state. But scholars generally agree that it must have been Sri Lanka because it is so stated in the 5th century Sri Lankan text Mahavamsa.[25] The Tamil term Eelam (Tamil: ஈழம், romanized: īḻam) was used to designate the whole island in Sangam literature.[26][27] The island was known under Chola rule as Mummudi Cholamandalam («realm of the three crowned Cholas»).[28]

Ancient Greek geographers called it Taprobanā (Ancient Greek: Ταπροβανᾶ) or Taprobanē (Ταπροβανῆ)[29] from the word Tambapanni. The Persians and Arabs referred to it as Sarandīb (the origin of the word «serendipity») from Sanskrit Siṃhaladvīpaḥ.[30][31] Ceilão, the name given to Sri Lanka by the Portuguese Empire when it arrived in 1505,[32] was transliterated into English as Ceylon.[33] As a British crown colony, the island was known as Ceylon; it achieved independence as the Dominion of Ceylon in 1948.

The country is now known in Sinhala as Śrī Laṅkā (Sinhala: ශ්රී ලංකා) and in Tamil as Ilaṅkai (Tamil: இலங்கை, IPA: [iˈlaŋɡaɪ]). In 1972, its formal name was changed to «Free, Sovereign and Independent Republic of Sri Lanka». Later, on 7 September 1978, it was changed to the «Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka».[34][35] As the name Ceylon still appears in the names of a number of organisations, the Sri Lankan government announced in 2011 a plan to rename all those over which it has authority.[36]

History

Prehistoric Sri Lanka

The pre-history of Sri Lanka goes back 125,000 years and possibly even as far back as 500,000 years.[37] The era spans the Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, and early Iron Ages. Among the Paleolithic human settlements discovered in Sri Lanka, Pahiyangala (37,000 BP), named after the Chinese traveller monk Faxian;[38] Batadombalena (28,500 BP);[39] and Belilena (12,000 BP) are the most important. In these caves, archaeologists have found the remains of anatomically modern humans which they have named Balangoda Man, and other evidence[40] suggesting that they may have engaged in agriculture and kept domestic dogs for driving game.[41]

The earliest inhabitants of Sri Lanka were probably ancestors of the Vedda people,[42] an indigenous people numbering approximately 2,500 living in modern-day Sri Lanka.

During the protohistoric period (1000–500 BCE) Sri Lanka was culturally united with southern India,[43] and shared the same megalithic burials, pottery, iron technology, farming techniques and megalithic graffiti.[44][45] This cultural complex spread from southern India along with Dravidian clans such as the Velir, prior to the migration of Prakrit speakers.[46][47][44]

One of the first written references to the island is found in the Indian epic Ramayana, which provides details of a kingdom named Lanka, that was created by the divine sculptor Vishvakarma for Kubera, the God of Wealth.[48] It is said that Kubera was overthrown by his rakshasa stepbrother, Ravana.[49]

Ancient Sri Lanka

According to the Mahāvamsa, a Pāḷi chronicle written in the 5th century CE, the original inhabitants of Sri Lanka are said to be the Yakshas and Nagas. Ancient cemeteries that were used before 600 BCE have also been discovered in Sri Lanka.[50] Sinhalese history traditionally starts in 543 BCE with the arrival of Prince Vijaya, a semi-legendary prince who sailed with 700 followers to Sri Lanka, after being expelled from Vanga Kingdom (present-day Bengal).[51] He established the Kingdom of Tambapanni, near modern-day Mannar. Vijaya (Singha) is the first of the approximately 189 monarchs of Sri Lanka described in chronicles such as the Dipavamsa, Mahāvaṃsa, Cūḷavaṃsa, and Rājāvaliya.[52]

Once Prakrit speakers had attained dominance on the island, the Mahavamsa further recounts the later migration of royal brides and service castes from the Tamil Pandya Kingdom to the Anuradhapura Kingdom in the early historic period.[53]

The Anuradhapura period (377 BCE – 1017 CE) began with the establishment of the Anuradhapura Kingdom in 380 BCE during the reign of Pandukabhaya. Thereafter, Anuradhapura served as the capital city of the country for nearly 1,400 years.[54] Ancient Sri Lankans excelled at building certain types of structures such as tanks, dagobas and palaces.[55] Society underwent a major transformation during the reign of Devanampiya Tissa, with the arrival of Buddhism from India. In 250 BCE,[56] Mahinda, a bhikkhu and the son of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka arrived in Mihintale carrying the message of Buddhism.[57] His mission won over the monarch, who embraced the faith and propagated it throughout the Sinhalese population.[58]

Succeeding kingdoms of Sri Lanka would maintain many Buddhist schools and monasteries and support the propagation of Buddhism into other countries in Southeast Asia. Sri Lankan Bhikkhus studied in India’s famous ancient Buddhist University of Nalanda, which was destroyed by Bakhtiyar Khilji. It is probable that many of the scriptures from Nalanda are preserved in Sri Lanka’s many monasteries and that the written form of the Tripiṭaka, including Sinhalese Buddhist literature, were part of the University of Nalanda.[59] In 245 BCE, bhikkhuni Sanghamitta arrived with the Jaya Sri Maha Bodhi tree, which is considered to be a sapling from the historical Bodhi Tree under which Gautama Buddha became enlightened.[60] It is considered the oldest human-planted tree (with a continuous historical record) in the world. (Bodhivamsa)[61][62]

Sri Lanka experienced the first of many foreign invasions during the reign of Suratissa, who was defeated by two horse traders named Sena and Guttika from South India.[58] The next invasion came immediately in 205 BCE by a Chola named Elara, who overthrew Asela and ruled the country for 44 years. Dutugamunu, the eldest son of the southern regional sub-king, Kavan Tissa, defeated Elara in the Battle of Vijithapura. During its two and a half millennia of existence, the Sinhala Kingdom was invaded at least eight times by neighbouring South Indian dynasties such as the Chola, Pandya, Chera, and Pallava. There also were incursions by the kingdoms of Kalinga (modern Odisha) and from the Malay Peninsula as well.

The Sigiriya («Lion Rock»), a rock fortress and city, built by King Kashyapa (477–495 CE) as a new more defensible capital. It was also used as a Buddhist monastery after the capital was moved back to Anuradhapura.

The Fourth Buddhist Council of Theravada Buddhism was held at the Anuradhapura Maha Viharaya in Sri Lanka under the patronage of Valagamba of Anuradhapura in 25 BCE. The council was held in response to a year in which the harvests in Sri Lanka were particularly poor and many Buddhist monks subsequently died of starvation. Because the Pāli Canon was at that time oral literature maintained in several recensions by dhammabhāṇakas (dharma reciters), the surviving monks recognised the danger of not writing it down so that even if some of the monks whose duty it was to study and remember parts of the Canon for later generations died, the teachings would not be lost.[63] After the council, palm-leaf manuscripts containing the completed Canon were taken to other countries such as Burma, Thailand, Cambodia and Laos.

Sri Lanka was the first Asian country known to have a female ruler: Anula of Anuradhapura (r. 47–42 BCE).[64] Sri Lankan monarchs undertook some remarkable construction projects such as Sigiriya, the so-called «Fortress in the Sky», built during the reign of Kashyapa I of Anuradhapura, who ruled between 477 and 495. The Sigiriya rock fortress is surrounded by an extensive network of ramparts and moats. Inside this protective enclosure were gardens, ponds, pavilions, palaces and other structures.[65][66]

In 993 CE, the invasion of Chola emperor Rajaraja I forced the then Sinhalese ruler Mahinda V to flee to the southern part of Sri Lanka. Taking advantage of this situation, Rajendra I, son of Rajaraja I, launched a large invasion in 1017. Mahinda V was captured and taken to India, and the Cholas sacked the city of Anuradhapura causing the fall of Anuradhapura Kingdom. Subsequently, they moved the capital to Polonnaruwa.[67]

Post-classical Sri Lanka

Following a 17-year-long campaign, Vijayabahu I successfully drove the Chola out of Sri Lanka in 1070, reuniting the country for the first time in over a century.[68][69] Upon his request, ordained monks were sent from Burma to Sri Lanka to re-establish Buddhism, which had almost disappeared from the country during the Chola reign.[70] During the medieval period, Sri Lanka was divided into three sub-territories, namely, Ruhunu, Pihiti and Maya.[71]

The seated image of Gal Vihara in Polonnaruwa, 12th century, which depicts the dhyana mudra, shows signs of Mahayana influence.

Sri Lanka’s irrigation system was extensively expanded during the reign of Parākramabāhu the Great (1153–1186).[72] This period is considered as a time when Sri Lanka was at the height of its power.[73][74] He built 1,470 reservoirs – the highest number by any ruler in Sri Lanka’s history – repaired 165 dams, 3,910 canals, 163 major reservoirs, and 2,376 mini-reservoirs.[75] His most famous construction is the Parakrama Samudra,[76] the largest irrigation project of medieval Sri Lanka. Parākramabāhu’s reign is memorable for two major campaigns – in the south of India as part of a Pandyan war of succession, and a punitive strike against the kings of Ramanna (Burma) for various perceived insults to Sri Lanka.[77]

After his demise, Sri Lanka gradually decayed in power. In 1215, Kalinga Magha, an invader with uncertain origins, identified as the founder of the Jaffna kingdom, invaded and captured the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa. He sailed from Kalinga[75] 690 nautical miles on 100 large ships with a 24,000 strong army. Unlike previous invaders, he looted, ransacked and destroyed everything in the ancient Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa Kingdoms beyond recovery.[78] His priorities in ruling were to extract as much as possible from the land and overturn as many of the traditions of Rajarata as possible. His reign saw the massive migration of native Sinhalese people to the south and west of Sri Lanka, and into the mountainous interior, in a bid to escape his power.[79][80]

Sri Lanka never really recovered from the impact of Kalinga Magha’s invasion. King Vijayabâhu III, who led the resistance, brought the kingdom to Dambadeniya. The north, in the meanwhile, eventually evolved into the Jaffna kingdom.[79][80] The Jaffna kingdom never came under the rule of any kingdom of the south except on one occasion; in 1450, following the conquest led by king Parâkramabâhu VI’s adopted son, Prince Sapumal.[81] He ruled the North from 1450 to 1467 CE.[82]

The next three centuries starting from 1215 were marked by kaleidoscopically shifting collections of capitals in south and central Sri Lanka, including Dambadeniya, Yapahuwa, Gampola, Raigama, Kotte,[83] Sitawaka, and finally, Kandy. In 1247, the Malay kingdom of Tambralinga which was a vassal of the Srivijaya Empire led by their king Chandrabhanu[84] briefly invaded Sri Lanka from Insular Southeast Asia. They were then expelled by the South Indian Pandyan Dynasty.[85] However, this temporary invasion reinforced the steady flow of the presence of various Austronesian merchant ethnic groups, from Sumatrans (Indonesia) to Lucoes (Philippines) into Sri Lanka which occurred since 200 BCE.[86] Chinese admiral Zheng He and his naval expeditionary force landed at Galle, Sri Lanka in 1409 and got into battle with the local king Vira Alakesvara of Gampola. Zheng He captured King Vira Alakesvara and later released him.[87][88][89][90] Zheng He erected the Galle Trilingual Inscription, a stone tablet at Galle written in three languages (Chinese, Tamil, and Persian), to commemorate his visit.[91][92] The stele was discovered by S. H. Thomlin at Galle in 1911 and is now preserved in the Colombo National Museum.

Early Modern Sri Lanka

A 17th-century engraving of Dutch explorer Joris van Spilbergen meeting with King Vimaladharmasuriya in 1602

The early modern period of Sri Lanka begins with the arrival of Portuguese soldier and explorer Lourenço de Almeida, the son of Francisco de Almeida, in 1505.[93] In 1517, the Portuguese built a fort at the port city of Colombo and gradually extended their control over the coastal areas. In 1592, after decades of intermittent warfare with the Portuguese, Vimaladharmasuriya I moved his kingdom to the inland city of Kandy, a location he thought more secure from attack.[94] In 1619, succumbing to attacks by the Portuguese, the independent existence of the Jaffna kingdom came to an end.[95]

During the reign of the Rajasinha II, Dutch explorers arrived on the island. In 1638, the king signed a treaty with the Dutch East India Company to get rid of the Portuguese who ruled most of the coastal areas.[96] The following Dutch–Portuguese War resulted in a Dutch victory, with Colombo falling into Dutch hands by 1656. The Dutch remained in the areas they had captured, thereby violating the treaty they had signed in 1638. The Burgher people, a distinct ethnic group, emerged as a result of intermingling between the Dutch and native Sri Lankans in this period.[97]

The Kingdom of Kandy was the last independent monarchy of Sri Lanka.[98] In 1595, Vimaladharmasurya brought the sacred Tooth Relic—the traditional symbol of royal and religious authority amongst the Sinhalese—to Kandy and built the Temple of the Tooth.[98] In spite of on-going intermittent warfare with Europeans, the kingdom survived. Later, a crisis of succession emerged in Kandy upon king Vira Narendrasinha’s death in 1739. He was married to a Telugu-speaking Nayakkar princess from South India (Madurai) and was childless by her.[98]

Eventually, with the support of bhikku Weliwita Sarankara and ignoring the right of «Unambuwe Bandara», the crown passed to the brother of one of Narendrasinha’s princesses, overlooking Narendrasinha’s own son by a Sinhalese concubine.[99] The new king was crowned Sri Vijaya Rajasinha later that year. Kings of the Nayakkar dynasty launched several attacks on Dutch controlled areas, which proved to be unsuccessful.[100]

During the Napoleonic Wars, fearing that French control of the Netherlands might deliver Sri Lanka to the French, Great Britain occupied the coastal areas of the island (which they called Ceylon) with little difficulty in 1796.[101] Two years later, in 1798, Sri Rajadhi Rajasinha, third of the four Nayakkar kings of Sri Lanka, died of a fever. Following his death, a nephew of Rajadhi Rajasinha, eighteen-year-old Kannasamy, was crowned.[102] The young king, now named Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, faced a British invasion in 1803 but successfully retaliated. The First Kandyan War ended in a stalemate.[102]

By then the entire coastal area was under the British East India Company as a result of the Treaty of Amiens. On 14 February 1815, Kandy was occupied by the British in the second Kandyan War, ending Sri Lanka’s independence.[102] Sri Vikrama Rajasinha, the last native monarch of Sri Lanka, was exiled to India.[103] The Kandyan Convention formally ceded the entire country to the British Empire. Attempts by Sri Lankan noblemen to undermine British power in 1818 during the Uva Rebellion were thwarted by Governor Robert Brownrigg.[104]

The beginning of the modern period of Sri Lanka is marked by the Colebrooke-Cameron reforms of 1833.[105] They introduced a utilitarian and liberal political culture to the country based on the rule of law and amalgamated the Kandyan and maritime provinces as a single unit of government.[105] An executive council and a legislative council were established, later becoming the foundation of a representative legislature. By this time, experiments with coffee plantations were largely successful.[106]

Soon, coffee became the primary commodity export of Sri Lanka. Falling coffee prices as a result of the depression of 1847 stalled economic development and prompted the governor to introduce a series of taxes on firearms, dogs, shops, boats, etc., and to reintroduce a form of rajakariya, requiring six days free labour on roads or payment of a cash equivalent.[106] These harsh measures antagonised the locals, and another rebellion broke out in 1848.[107] A devastating leaf disease, Hemileia vastatrix, struck the coffee plantations in 1869, destroying the entire industry within fifteen years.[108] The British quickly found a replacement: abandoning coffee, they began cultivating tea instead. Tea production in Sri Lanka thrived in the following decades. Large-scale rubber plantations began in the early 20th century.

By the end of the 19th century, a new educated social class transcending race and caste arose through British attempts to staff the Ceylon Civil Service and the legal, educational, engineering, and medical professions with natives.[109] New leaders represented the various ethnic groups of the population in the Ceylon Legislative Council on a communal basis. Buddhist and Hindu revivalism reacted against Christian missionary activities.[110][111] The first two decades in the 20th century are noted by the unique harmony among Sinhalese and Tamil political leadership, which has since been lost.[112]

The 1906 malaria outbreak in Ceylon actually started in the early 1900s, but the first case was documented in 1906.

In 1919, major Sinhalese and Tamil political organisations united to form the Ceylon National Congress, under the leadership of Ponnambalam Arunachalam,[113] pressing colonial masters for more constitutional reforms. But without massive popular support, and with the governor’s encouragement for «communal representation» by creating a «Colombo seat» that dangled between Sinhalese and Tamils, the Congress lost momentum towards the mid-1920s.[114]

The Donoughmore reforms of 1931 repudiated the communal representation and introduced universal adult franchise (the franchise stood at 4% before the reforms). This step was strongly criticised by the Tamil political leadership, who realised that they would be reduced to a minority in the newly created State Council of Ceylon, which succeeded the legislative council.[115][116] In 1937, Tamil leader G. G. Ponnambalam demanded a 50–50 representation (50% for the Sinhalese and 50% for other ethnic groups) in the State Council. However, this demand was not met by the Soulbury reforms of 1944–45.

Contemporary Sri Lanka

The formal ceremony marking the start of self-rule, with the opening of the first parliament at Independence Square

The Soulbury constitution ushered in dominion status, with independence proclaimed on 4 February 1948.[117] D. S. Senanayake became the first Prime Minister of Ceylon.[118] Prominent Tamil leaders including Ponnambalam and Arunachalam Mahadeva joined his cabinet.[115][119] The British Royal Navy remained stationed at Trincomalee until 1956. A countrywide popular demonstration against withdrawal of the rice rations resulted in the resignation of prime minister Dudley Senanayake.[120]

S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike was elected prime minister in 1956. His three-year rule had a profound impact through his self-proclaimed role of «defender of the besieged Sinhalese culture».[121] He introduced the controversial Sinhala Only Act, recognising Sinhala as the only official language of the government. Although partially reversed in 1958, the bill posed a grave concern for the Tamil community, which perceived in it a threat to their language and culture.[122][123][124]

The Federal Party (FP) launched a movement of non-violent resistance (satyagraha) against the bill, which prompted Bandaranaike to reach an agreement (Bandaranaike–Chelvanayakam Pact) with S. J. V. Chelvanayakam, leader of the FP, to resolve the looming ethnic conflict.[125] The pact proved ineffective in the face of ongoing protests by opposition and the Buddhist clergy. The bill, together with various government colonisation schemes, contributed much towards the political rancour between Sinhalese and Tamil political leaders.[126] Bandaranaike was assassinated by an extremist Buddhist monk in 1959.[127]

1960 saw the election of Sirimavo Bandaranaike as Ceylon’s Prime Minister and the first time in world history that the heads of both state and government in a country were female.

Sirimavo Bandaranaike, the widow of Bandaranaike, took office as prime minister in 1960, and withstood an attempted coup d’état in 1962. During her second term as prime minister, the government instituted socialist economic policies, strengthening ties with the Soviet Union and China, while promoting a policy of non-alignment. In 1971, Ceylon experienced a Marxist insurrection, which was quickly suppressed. In 1972, the country became a republic named Sri Lanka, repudiating its dominion status. Prolonged minority grievances and the use of communal emotionalism as an election campaign weapon by both Sinhalese and Tamil leaders abetted a fledgling Tamil militancy in the north during the 1970s.[128] The policy of standardisation by the Sirimavo government to rectify disparities created in university enrollment, which was in essence an affirmative action to assist geographically disadvantaged students to obtain tertiary education,[129] resulted in reducing the proportion of Tamil students at university level and acted as the immediate catalyst for the rise of militancy.[130][131] The assassination of Jaffna Mayor Alfred Duraiyappah in 1975 by the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) marked a crisis point.[132][133]

The government of J. R. Jayawardene swept to power in 1977, defeating the largely unpopular United Front government.[134] Jayawardene introduced a new constitution, together with a free-market economy and a powerful executive presidency modelled after that of France. It made Sri Lanka the first South Asian country to liberalise its economy.[135] Beginning in 1983, ethnic tensions were manifested in an on-and-off insurgency against the government by the LTTE. An LTTE attack on 13 soldiers resulted in the anti-Tamil race riots in July 1983, allegedly backed by Sinhalese hard-line ministers, which resulted in more than 150,000 Tamil civilians fleeing the island, seeking asylum in other countries.[136][137]

Lapses in foreign policy resulted in India strengthening the Tigers by providing arms and training.[138][139][140] In 1987, the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord was signed and the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) was deployed in northern Sri Lanka to stabilise the region by neutralising the LTTE.[141] The same year, the JVP launched its second insurrection in Southern Sri Lanka,[142] necessitating redeployment of the IPKF in 1990.[143] In October 1990, the LTTE expelled Sri Lankan Moors (Muslims by religion) from northern Sri Lanka.[144] In 2002, the Sri Lankan government and LTTE signed a Norwegian-mediated ceasefire agreement.[124]

The 2004 Asian tsunami killed over 30,000 and displaced over 500,000 people in Sri Lanka.[145][146] From 1985 to 2006, the Sri Lankan government and Tamil insurgents held four rounds of peace talks without success. Both LTTE and the government resumed fighting in 2006, and the government officially backed out of the ceasefire in 2008.[124] In 2009, under the Presidency of Mahinda Rajapaksa, the Sri Lanka Armed Forces defeated the LTTE, bringing an end to the civil war, and re-established control of the entire country by the Sri Lankan Government.[147] Overall, between 60,000 and 100,000 people were killed during the 26 years of conflict.[148][149]

Economic troubles in Sri Lanka began in 2019, when a severe economic crisis occurred caused by rapidly increasing foreign debt, massive government budget deficits due to tax cuts, a food crisis caused by mandatory organic farming along with a ban on chemical fertilizers, and a multitude of other factors.[150] The Sri Lankan Government officially declared the ongoing crisis to be the worst economic crisis in the country in 73 years.[151] In August 2021, a food emergency was declared.[152] In June 2022, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe declared the collapse of the Sri Lankan economy in parliament.[153] The crisis resulted in Sri Lanka defaulting on its $51 billion sovereign debt for the first time in its history, along with double-digit inflation, a crippling energy crisis that led to 15 hour power cuts, severe fuel shortages leading to the suspension of fuel to all non-essential vehicles, and more.[154][155] Due to the crisis, massive street protests erupted across the country, with protesters demanding the resignation of the then-incumbent President Gotabaya Rajapaksa. The protests culminated with the storming of the President’s House on July 9, 2022, and resulted in President Gotabaya Rajapaksa fleeing to Singapore[156] and later email his resignation to parliament, formally announcing his resignation and making him the first Sri Lankan president to resign in the middle of his term.[157] On the same day the President’s House was stormed, protesters stormed the private residence of the prime minister and burnt it down.[158]

On July 20, 2022, Ranil Wickremesinghe was elected as the ninth President via a parliamentarian election.[159]

Geography

Topographic map of Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, an island in South Asia shaped as a teardrop or a pear/mango,[160] lies on the Indian Plate, a major tectonic plate that was formerly part of the Indo-Australian Plate.[161] It is in the Indian Ocean southwest of the Bay of Bengal, between latitudes 5° and 10° N, and longitudes 79° and 82° E.[162] Sri Lanka is separated from the mainland portion of the Indian subcontinent by the Gulf of Mannar and Palk Strait. According to Hindu mythology, a land bridge existed between the Indian mainland and Sri Lanka. It now amounts to only a chain of limestone shoals remaining above sea level.[163] Legends claim that it was passable on foot up to 1480 CE, until cyclones deepened the channel.[164][165] Portions are still as shallow as 1 metre (3 ft), hindering navigation.[166] The island consists mostly of flat to rolling coastal plains, with mountains rising only in the south-central part. The highest point is Pidurutalagala, reaching 2,524 metres (8,281 ft) above sea level.

Sri Lanka has 103 rivers. The longest of these is the Mahaweli River, extending 335 kilometres (208 mi).[167] These waterways give rise to 51 natural waterfalls of 10 metres (33 ft) or more. The highest is Bambarakanda Falls, with a height of 263 metres (863 ft).[168] Sri Lanka’s coastline is 1,585 km (985 mi) long.[169] Sri Lanka claims an exclusive economic zone extending 200 nautical miles, which is approximately 6.7 times Sri Lanka’s land area. The coastline and adjacent waters support highly productive marine ecosystems such as fringing coral reefs and shallow beds of coastal and estuarine seagrasses.[170]

Sri Lanka has 45 estuaries and 40 lagoons.[169] Sri Lanka’s mangrove ecosystem spans over 7,000 hectares and played a vital role in buffering the force of the waves in the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami.[171] The island is rich in minerals such as ilmenite, feldspar, graphite, silica, kaolin, mica and thorium.[172][173] Existence of petroleum and gas in the Gulf of Mannar has also been confirmed, and the extraction of recoverable quantities is underway.[174]

Climate

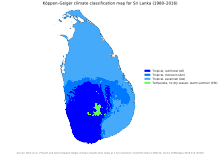

Sri Lanka map of Köppen climate classification

The climate is tropical and warm because of moderating effects of ocean winds. Mean temperatures range from 17 °C (62.6 °F) in the central highlands, where frost may occur for several days in the winter, to a maximum of 33 °C (91.4 °F) in low-altitude areas. Average yearly temperatures range from 28 °C (82.4 °F) to nearly 31 °C (87.8 °F). Day and night temperatures may vary by 14 °C (57.2 °F) to 18 °C (64.4 °F).[175]

The rainfall pattern is influenced by monsoon winds from the Indian Ocean and Bay of Bengal. The «wet zone» and some of the windward slopes of the central highlands receive up to 2,500 millimetres (98.4 in) of rain each year, but the leeward slopes in the east and northeast receive little rain. Most of the east, southeast, and northern parts of Sri Lanka constitute the «dry zone», which receives between 1,200 and 1,900 mm (47 and 75 in) of rain annually.[176]

The arid northwest and southeast coasts receive the least rain at 800 to 1,200 mm (31 to 47 in) per year. Periodic squalls occur and sometimes tropical cyclones bring overcast skies and rains to the southwest, northeast, and eastern parts of the island. Humidity is typically higher in the southwest and mountainous areas and depends on the seasonal patterns of rainfall.[177] An increase in average rainfall coupled with heavier rainfall events has resulted in recurrent flooding and related damages to infrastructure, utility supply and the urban economy.[178]

Flora and fauna

Western Ghats of India and Sri Lanka were included among the first 18 global biodiversity hotspots due to high levels of species endemism. The number of biodiversity hotspots has now increased to 34.[180] Sri Lanka has the highest biodiversity per unit area among Asian countries for flowering plants and all vertebrate groups except birds.[181] A remarkably high proportion of the species among its flora and fauna, 27% of the 3,210 flowering plants and 22% of the mammals, are endemic.[182] Sri Lanka supports a rich avifauna of that stands at 453 species and this include 240 species of birds that are known to breed in the country. 33 species are accepted by some ornithologists as endemic while some ornithologists consider only 27 are endemic and the remaining six are considered as proposed endemics.[183] Sri Lanka’s protected areas are administrated by two government bodies; The Department of Forest Conservation and the Department of Wildlife Conservation. Department of Wildlife Conservation administrates 61 wildlife sanctuaries, 22 national parks, four nature reserves, three strict nature reserves, and one jungle corridor while Department of Forest Conservation oversees 65 conservation forests and one national heritage wilderness area. 26.5% of the country’s land area is legally protected. This is a higher percentage of protected areas when compared to the rest of Asia.[184]

Sri Lanka contains four terrestrial ecoregions: Sri Lanka lowland rain forests, Sri Lanka montane rain forests, Sri Lanka dry-zone dry evergreen forests, and Deccan thorn scrub forests.[185] Flowering acacias flourish on the arid Jaffna Peninsula. Among the trees of the dry-land forests are valuable species such as satinwood, ebony, ironwood, mahogany and teak. The wet zone is a tropical evergreen forest with tall trees, broad foliage, and a dense undergrowth of vines and creepers. Subtropical evergreen forests resembling those of temperate climates flourish in the higher altitudes.[186]

Yala National Park in the southeast protects herds of elephant, deer, and peacocks. The Wilpattu National Park in the northwest, the largest national park, preserves the habitats of many water birds such as storks, pelicans, ibis, and spoonbills. The island has four biosphere reserves: Bundala, Hurulu Forest Reserve, the Kanneliya-Dediyagala-Nakiyadeniya, and Sinharaja.[187] Sinharaja is home to 26 endemic birds and 20 rainforest species, including the elusive red-faced malkoha, the green-billed coucal and the Sri Lanka blue magpie. The untapped genetic potential of Sinharaja flora is enormous. Of the 211 woody trees and lianas within the reserve, 139 (66%) are endemic. The total vegetation density, including trees, shrubs, herbs, and seedlings, has been estimated at 240,000 individuals per hectare. The Minneriya National Park borders the Minneriya Tank, which is an important source of water for elephants inhabiting the surrounding forests. Dubbed «The Gathering», the congregation of elephants can be seen on the tank-bed in the late dry season (August to October) as the surrounding water sources steadily disappear. The park also encompasses a range of micro-habitats which include classic dry zone tropical monsoonal evergreen forest, thick stands of giant bamboo, hilly pastures (patanas), and grasslands (talawas).[188]

During the Mahaweli Program of the 1970s and 1980s in northern Sri Lanka, the government set aside four areas of land totalling 1,900 km2 (730 sq mi) as national parks. Statistics of Sri Lanka’s forest cover show rapid deforestation from 1956 to 2010. In 1956, 44.2 percent of the country’s land area had forest cover. Forest cover depleted rapidly in recent decades; 29.6 percent in 1999, 28.7 percent in 2010.[189]

Government and politics

This section needs expansion with: is missing explication of the constitutional socialist nature of the republic that is reflected in the formal name of the country: «Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka». You can help by adding to it. (July 2022)

Sri Lanka is a democratic republic and a unitary state which is governed by a semi-presidential system.[190] Sri Lanka is the oldest democracy in Asia.[191] Most provisions of the constitution can be amended by a two-thirds majority in parliament. The amendment of certain basic features such as the clauses on language, religion, and reference to Sri Lanka as a unitary state require both a two-thirds majority and approval in a nationwide referendum.

In common with many democracies, the Sri Lankan government has three branches:

- Executive: The President of Sri Lanka is the head of state; the commander in chief of the armed forces; chief executive, and is popularly elected for a five-year term.[192] The president heads the cabinet and appoints ministers from elected members of parliament.[193] The president is immune from legal proceedings while in the office with respect to any acts done or omitted to be done by him or her in either an official or private capacity.[194] Following the passage of the 19th amendment to the constitution in 2015, the president has two terms, which previously stood at no term limit.

- Legislative: The Parliament of Sri Lanka is a unicameral 225-member legislature with 196 members elected in multi-seat constituencies and 29 elected by proportional representation.[195] Members are elected by universal suffrage for a five-year term. The president may summon, suspend, or end a legislative session and dissolve Parliament at any time after four and a half years. The parliament reserves the power to make all laws.[196] The president’s deputy and head of government, the prime minister, leads the ruling party in parliament and shares many executive responsibilities, mainly in domestic affairs.

The Supreme Court of Sri Lanka, Colombo

- Judicial: Sri Lanka’s judiciary consists of a Supreme Court – the highest and final superior court of record,[196] a Court of Appeal, High Courts and a number of subordinate courts. The highly complex legal system reflects diverse cultural influences.[197] Criminal law is based almost entirely on British law. Basic civil law derives from Roman-Dutch law. Laws pertaining to marriage, divorce, and inheritance are communal.[198] Because of ancient customary practices and religion, the Sinhala customary law (Kandyan law), the Thesavalamai, and Sharia law are followed in special cases.[199] The president appoints judges to the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, and the High Courts. A judicial service commission, composed of the chief justice and two Supreme Court judges, appoints, transfers, and dismisses lower court judges.

Politics

| National symbols of Sri Lanka | |

|---|---|

| Flag | Lion Flag |

| Emblem | Gold Lion Passant |

| Anthem | «Sri Lanka Matha» |

| Butterfly | Sri Lankan birdwing |

| Animal | Grizzled giant squirrel |

| Bird | Sri Lanka junglefowl |

| Flower | Blue water lily |

| Tree | Ceylon ironwood (nā) |

| Sport | Volleyball |

| Source: [200][201] | |

|

The current political culture in Sri Lanka is a contest between two rival coalitions led by the centre-left and progressive United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA), an offspring of Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), and the comparatively right-wing and pro-capitalist United National Party (UNP).[202] Sri Lanka is essentially a multi-party democracy with many smaller Buddhist, socialist, and Tamil nationalist political parties. As of July 2011, the number of registered political parties in the country is 67.[203] Of these, the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), established in 1935, is the oldest.[204]

The UNP, established by D. S. Senanayake in 1946, was until recently the largest single political party.[205] It is the only political group which had representation in all parliaments since independence.[205] SLFP was founded by S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike in July 1951.[206] SLFP registered its first victory in 1956, defeating the ruling UNP in the 1956 Parliamentary election.[206] Following the parliamentary election in July 1960, Sirimavo Bandaranaike became the prime minister and the world’s first elected female head of government.[207]

G. G. Ponnambalam, the Tamil nationalist counterpart of S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike,[208] founded the All Ceylon Tamil Congress (ACTC) in 1944. Objecting to Ponnambalam’s cooperation with D. S. Senanayake, a dissident group led by S.J.V. Chelvanayakam broke away in 1949 and formed the Illankai Tamil Arasu Kachchi (ITAK), also known as the Federal Party, becoming the main Tamil political party in Sri Lanka for next two decades.[209] The Federal Party advocated a more aggressive stance toward the Sinhalese.[210] With the constitutional reforms of 1972, the ACTC and ITAK created the Tamil United Front (later Tamil United Liberation Front). Following a period of turbulence as Tamil militants rose to power in the late 1970s, these Tamil political parties were succeeded in October 2001 by the Tamil National Alliance.[210][211] Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna, a Marxist–Leninist political party founded by Rohana Wijeweera in 1965, serves as a third force in the current political context.[212] It endorses leftist policies which are more radical than the traditionalist leftist politics of the LSSP and the Communist Party.[210] Founded in 1981, the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress is the largest Muslim political party in Sri Lanka.[213]

President Mahinda Rajapaksa lost the 2015 presidential elections, ending his ten-year presidency. However, his successor as Sri Lankan President, Maithripala Sirisena, decided not to seek re-election in 2019.[214] The Rajapaksa family regained power in November 2019 presidential elections when Mahinda’s younger brother and former wartime defence chief Gotabaya Rajapaksa won the election, and he was later sworn in as the new president of Sri Lanka.[215][216] Their firm grip of power was consolidated in the parliamentary elections in August 2020. The family’s political party, Sri Lanka People’s Front (known by its Sinhala initials SLPP), obtained a landslide victory and a clear majority in the parliament. Five members of the Rajapaksa family won seats in the new parliament. Former president Mahinda Rajapaksa became the new prime minister.[217]

In 2022, a political crisis started due to the power struggle between President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and the Parliament of Sri Lanka. The crisis was fuelled by anti-government protests and demonstrations by the public and also due to the worsening economy of Sri Lanka since 2019. The anti-government sentiment across various parts of Sri Lanka has triggered unprecedented political instability, creating shockwaves in the political arena.[218]

On July 20, 2022, Ranil Wickremesinghe was elected as the ninth President via a parliamentarian election.[219]

Administrative divisions

For administrative purposes, Sri Lanka is divided into nine provinces[220] and twenty-five districts.[221]

Provinces

Provinces in Sri Lanka have existed since the 19th century, but they had no legal status until 1987 when the 13th Amendment of the 1978 constitution established provincial councils after several decades of increasing demand for a decentralisation of the government.[222] Each provincial council is an autonomous body not under the authority of any ministry. Some of its functions had been undertaken by central government ministries, departments, corporations, and statutory authorities,[222] but authority over land and police is not as a rule given to provincial councils.[223][224] Between 1989 and 2006, the Northern and Eastern provinces were temporarily merged to form the North-East Province.[225][226] Prior to 1987, all administrative tasks for the provinces were handled by a district-based civil service which had been in place since colonial times. Now each province is administered by a directly elected provincial council:

| Province | Capital | Area (km2) |

Population (2012)[227] | Density (Persons per km2) |

Provincial GDP share (%) (2019) | Sri Lanka Prosperity Index (2019)[229] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central | Kandy | 5,674 | 2,571,557 | 453 | 11.5 | 0.386 |

| Eastern | Trincomalee | 9,996 | 1,555,510 | 155 | 5.7 | 0.107 |

| North Central | Anuradhapura | 10,714 | 1,266,663 | 118 | 5.4 | 0.249 |

| Northern | Jaffna | 8,884 | 1,061,315 | 119 | 4.7 | 0.373 |

| North Western | Kurunegala | 7,812 | 2,380,861 | 305 | 10.7 | 0.310 |

| Sabaragamuwa | Ratnapura | 4,902 | 1,928,655 | 393 | 7.6 | 0.254 |

| Southern | Galle | 5,559 | 2,477,285 | 446 | 9.9 | 0.458 |

| Uva | Badulla | 8,488 | 1,266,463 | 149 | 5.4 | 0.025 |

| Western | Colombo | 3,709 | 5,851,130 | 1,578 | 39.1 | 1.615 |

| Sri Lanka | Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte and Colombo | 65,610 | 20,359,439 | 310 | 100 | 0.802 |

Each district is administered under a district secretariat. The districts are further subdivided into 256 divisional secretariats, and these to approximately 14,008 Grama Niladhari divisions.[230] The districts are known in Sinhala as disa and in Tamil as māwaddam. Originally, a disa (usually rendered into English as Dissavony) was a duchy, notably Matale and Uva.

There are three other types of local authorities: municipal councils (18), urban councils (13) and pradeshiya sabha, also called pradesha sabhai (256).[231] Local authorities were originally based on feudal counties named korale and rata, and were formerly known as «D.R.O. divisions» after the divisional revenue officer.[232] Later, the D.R.O.s became «assistant government agents,» and the divisions were known as «A.G.A. divisions». These divisional secretariats are currently administered by a divisional secretary.

Foreign relations

Sri Lanka is a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). While ensuring that it maintains its independence, Sri Lanka has cultivated relations with India.[233] Sri Lanka became a member of the United Nations in 1955. Today, it is also a member of the Commonwealth, the SAARC, the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the Asian Development Bank, and the Colombo Plan.

The United National Party has traditionally favoured links with the West, while the Sri Lanka Freedom Party has favoured links with the East.[233] Sri Lankan Finance Minister J. R. Jayewardene, together with then Australian Foreign Minister Sir Percy Spencer, proposed the Colombo Plan at the Commonwealth Foreign Minister’s Conference held in Colombo in 1950.[234] At the San Francisco Peace Conference in 1951, while many countries were reluctant, Sri Lanka argued for a free Japan and refused to accept payment of reparations for World War II damage because it believed it would harm Japan’s economy.[235] Sri Lanka-China relations started as soon as the People’s Republic of China was formed in 1949. The two countries signed an important Rice-Rubber Pact in 1952.[236] Sri Lanka played a vital role at the Asian–African Conference in 1955, which was an important step in the crystallisation of the NAM.[237]

The Bandaranaike government of 1956 significantly changed the pro-western policies set by the previous UNP government. It recognised Cuba under Fidel Castro in 1959. Shortly afterward, Cuba’s revolutionary Che Guevara paid a visit to Sri Lanka.[238] The Sirima-Shastri Pact of 1964[239] and Sirima-Gandhi Pact of 1974[240] were signed between Sri Lankan and Indian leaders in an attempt to solve the long-standing dispute over the status of plantation workers of Indian origin. In 1974, Kachchatheevu, a small island in Palk Strait, was formally ceded to Sri Lanka.[241] By this time, Sri Lanka was strongly involved in the NAM, and the fifth NAM summit was held in Colombo in 1976.[242] The relationship between Sri Lanka and India became tense under the government of J. R. Jayawardene.[143][243] As a result, India intervened in the Sri Lankan Civil War and subsequently deployed an Indian Peace Keeping Force in 1987.[244] In the present, Sri Lanka enjoys extensive relations with China,[245] Russia,[246] and Pakistan.[247]

Military

The Sri Lanka Armed Forces, comprising the Sri Lanka Army, the Sri Lanka Navy, and the Sri Lanka Air Force, come under the purview of the Ministry of Defence.[248] The total strength of the three services is around 346,000 personnel, with nearly 36,000 reserves.[249] Sri Lanka has not enforced military conscription.[250] Paramilitary units include the Special Task Force, the Civil Security Force, and the Sri Lanka Coast Guard.[251][252]

Since independence in 1948, the primary focus of the armed forces has been internal security, crushing three major insurgencies, two by Marxist militants of the JVP and a 26-year-long conflict with the LTTE. The armed forces have been in a continuous mobilised state for the last 30 years.[253][254] The Sri Lankan Armed Forces have engaged in United Nations peacekeeping operations since the early 1960s, contributing forces to permanent contingents deployed in several UN peacekeeping missions in Chad, Lebanon, and Haiti.[255]

Economy

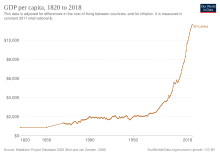

Development of real GDP per capita, 1820 to 2018

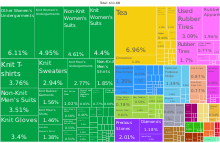

A proportional representation of Sri Lanka exports, 2019

According to the International Monetary Fund, Sri Lanka’s GDP in terms of purchasing power parity is the second highest in the South Asian region in terms of per capita income. In the 19th and 20th centuries, Sri Lanka became a plantation economy famous for its production and export of cinnamon, rubber, and Ceylon tea, which remains a trademark national export.[256] The development of modern ports under British rule raised the strategic importance of the island as a centre of trade.[257] From 1948 to 1977, socialism strongly influenced the government’s economic policies. Colonial plantations were dismantled, industries were nationalised, and a welfare state established. In 1977, the free market economy was introduced to the country, incorporating privatisation, deregulation, and the promotion of private enterprise.[135]

While the production and export of tea, rubber, coffee, sugar, and other commodities remain important, industrialisation has increased the importance of food processing, textiles, telecommunications, and finance. The country’s main economic sectors are tourism, tea export, clothing, rice production, and other agricultural products. In addition to these economic sectors, overseas employment, especially in the Middle East, contributes substantially in foreign exchange.[258]

As of 2020, the service sector makes up 59.7% of GDP, the industrial sector 26.2%, and the agriculture sector 8.4%.[259] The private sector accounts for 85% of the economy.[260] China, India and the United States are Sri Lanka’s largest trading partners.[261] Economic disparities exist between the provinces with the Western Province contributing 45.1% of the GDP and the Southern Province and the Central Province contributing 10.7% and 10%, respectively.[262] With the end of the war, the Northern Province reported a record 22.9% GDP growth in 2010.[263]

Sri Lanka’s most widely known export, Ceylon tea, which ISO considers the cleanest tea in the world in terms of pesticide residues. Sri Lanka is also the world’s 2nd largest exporter of tea.[264]

The per capita income of Sri Lanka doubled from 2005 to 2011.[265] During the same period, poverty dropped from 15.2% to 7.6%, unemployment rate dropped from 7.2% to 4.9%, market capitalisation of the Colombo Stock Exchange quadrupled, and the budget deficit doubled.[258] 99% of the households in Sri Lanka are electrified; 93.2% of the population have access to safe drinking water; and 53.1% have access to pipe-borne water.[259] Income inequality has also dropped in recent years, indicated by a Gini coefficient of 0.36 in 2010.[266]

The 2011 Global Competitiveness Report, published by the World Economic Forum, described Sri Lanka’s economy as transitioning from the factor-driven stage to the efficiency-driven stage and that it ranked 52nd in global competitiveness.[267] Also, out of the 142 countries surveyed, Sri Lanka ranked 45th in health and primary education, 32nd in business sophistication, 42nd in innovation, and 41st in goods market efficiency. In 2016, Sri Lanka ranked 5th in the World Giving Index, registering high levels of contentment and charitable behaviour in its society.[268] In 2010, The New York Times placed Sri Lanka at the top of its list of 31 places to visit.[269] S&P Dow Jones Indices classifies Sri Lanka as a frontier market as of 2018.[270] Sri Lanka ranks well above other South Asian countries in the Human Development Index (HDI) with an index of 0.750.

By 2016, the country’s debt soared as it was developing its infrastructure to the point of near bankruptcy which required a bailout from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).[271] The IMF had agreed to provide a US$1.5 billion bailout loan in April 2016 after Sri Lanka provided a set of criteria intended to improve its economy. By the fourth quarter of 2016, the debt was estimated to be $64.9 billion. Additional debt had been incurred in the past by state-owned organisations and this was said to be at least $9.5 billion. Since early 2015, domestic debt increased by 12% and external debt by 25%.[272] In November 2016, the IMF reported that the initial disbursement was larger than US$150 million originally planned, a full US$162.6 million (SDR 119.894 million). The agency’s evaluation for the first tranche was cautiously optimistic about the future. Under the program, the Sri Lankan government implemented a new Inland Revenue Act and an automatic fuel pricing formula which was noted by the IMF in its fourth review. In 2018 China agreed to bail out Sri Lanka with a loan of $1.25 billion to deal with foreign debt repayment spikes in 2019 to 2021.[273][274][275]

In September 2021, Sri Lanka declared a major economic crisis.[276] The Chief of its Central Bank has stepped down amid the crisis.[277] The Parliament has declared emergency regulations due to the crisis, seeking to ban «food hoarding».[278][279]

Tourism, which provided the economy with an input of foreign currency, has been significantly impacted as a result of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.[280]

Transport

Sri Lanka has an extensive road network for inland transportation. With more than 100,000 km (62,000 mi) of paved roads,[281] it has one of the highest road densities in the world (1.5 km or 0.93 mi of paved roads per every 1 km2 or 0.39 sq mi of land). The road network consists of 35 A-Grade highways and four controlled-access highways.[282][283] A and B grade roads are national (arterial) highways administered by Road Development Authority.[284] C and D grade roads are provincial roads coming under the purview of the Provincial Road Development Authority of the respective province. The other roads are local roads falling under local government authorities.

The railway network, operated by the state-run National Railway operator Sri Lanka Railways, spans 1,447 kilometres (900 mi).[285] Sri Lanka also has three deep-water ports at Colombo, Galle, and Trincomalee, in addition to the newest port being built at Hambantota.

Transition to biological agriculture

In June 2021, Sri Lanka imposed a nationwide ban on inorganic fertilisers and pesticides. The program was welcomed by its advisor Vandana Shiva,[286] but ignored critical voices from scientific and farming community who warned about possible collapse of farming,[287][288][289][290][291] including financial crisis due to devaluation of national currency pivoted around tea industry.[287] The situation in the tea industry was described as critical, with farming under the organic program being described as ten times more expensive and producing half of the yield by the farmers.[292] In September 2021 the government declared an economic emergency, as the situation was further aggravated by falling national currency exchange rate, inflation rising as a result of high food prices, and pandemic restrictions in tourism which further decreased country’s income.[276]

In November 2021, Sri Lanka abandoned its plan to become the world’s first organic farming nation following rising food prices and weeks of protests against the plan.[293] As of December 2021, the damage to agricultural production was already done, with prices having risen substantially for vegetables in Sri Lanka, and time needed to recover from the crisis. The ban on fertiliser has been lifted for certain crops, but the price of urea has risen internationally due to the price for oil and gas.[280] Jeevika Weerahewa, a senior lecturer at the University of Peradeniya, predicted that the ban would reduce the paddy harvest in 2022 by an unprecedented 50%.[294]

Demographics

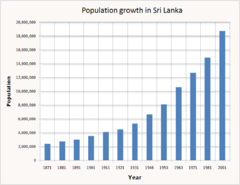

Sri Lanka’s population, (1871–2001)

Sri Lanka has roughly 22,156,000 people and an annual population growth rate of 0.5%. The birth rate is 13.8 births per 1,000 people, and the death rate is 6.0 deaths per 1,000 people.[259] Population density is highest in western Sri Lanka, especially in and around the capital. Sinhalese constitute the largest ethnic group in the country, with 74.8% of the total population.[295] Sri Lankan Tamils are the second major ethnic group in the island, with a percentage of 11.2%. Moors comprise 9.2%. There are also small ethnic groups such as the Burghers (of mixed European descent) and Malays from Southeast Asia. Moreover, there is a small population of Vedda people who are believed to be the original indigenous group to inhabit the island.[296]

Largest cities

|

Largest cities or towns in Sri Lanka (2012 Department of Census and Statistics enumeration)[297] |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | |

| Colombo Kaduwela |

1 | Colombo | Western | 561,314 | 11 | Galle | Southern | 86,333 |

| 2 | Kaduwela | Western | 252,041 | 12 | Batticaloa | Eastern | 86,227 | |

| 3 | Maharagama | Western | 196,423 | 13 | Jaffna | Northern | 80,829 | |

| 4 | Kesbewa | Western | 185,122 | 14 | Matara | Southern | 74,193 | |

| 5 | Dehiwala-Mount Lavinia | Western | 184,468 | 15 | Gampaha | Western | 62,335 | |

| 6 | Moratuwa | Western | 168,280 | 16 | Katunayake | Western | 60,915 | |

| 7 | Negombo | Western | 142,449 | 17 | Boralesgamuwa | Western | 60,110 | |

| 8 | Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte | Western | 107,925 | 18 | Kolonnawa | Western | 60,044 | |

| 9 | Kalmunai | Eastern | 99,893 | 19 | Anuradhapura | North Central | 50,595 | |

| 10 | Kandy | Central | 98,828 | 20 | Trincomalee | Eastern | 48,351 |

Languages

Sinhala and Tamil are the two official languages.[298] The constitution defines English as the link language. English is widely used for education, scientific and commercial purposes. Members of the Burgher community speak variant forms of Portuguese Creole and Dutch with varying proficiency, while members of the Malay community speak a form of Creole Malay that is unique to the island.[299]

Religion

Religion in Sri Lanka (2012 census)[300][301]

Others (0.05%)

Buddhism is the largest and is considered as an «Official religion» of Sri Lanka under Chapter II, Article 9, «The Republic of Sri Lanka shall give to Buddhism the foremost place and accordingly it shall be the duty of the State to protect and foster the Buddha Sasana».[302][303]

Buddhism is practised by 70.2% of the Sri Lankan population with most being predominantly from Theravada school of thought.[304] Most Buddhists are of the Sinhalese ethnic group with minority Tamils. Buddhism was introduced to Sri Lanka in the 2nd century BCE by venerable Mahinda Maurya.[304] A sapling of the Bodhi Tree under which the Buddha attained enlightenment was brought to Sri Lanka during the same time. The Pāli Canon (Thripitakaya), having previously been preserved as an oral tradition, was first committed to writing in Sri Lanka around 30 BCE.[305] Sri Lanka has the longest continuous history of Buddhism of any predominantly Buddhist nation.[304] During periods of decline, the Sri Lankan monastic lineage was revived through contact with Thailand and Burma.[305]

Although Hindus in Sri Lanka a religious minority, Hinduism has been present in Sri Lanka at least since the 2nd century BCE.[306] Hinduism was the dominant religion in Sri Lanka before the arrival of Buddhism in the 3rd century BCE. Buddhism was introduced into Sri Lanka by Mahinda, the son of Emperor Ashoka, during the reign of King Devanampiya Tissa;[307] the Sinhalese embraced Buddhism and Tamils remain Hindus in Sri Lanka. However, it was activity from across the Palk Strait that truly set the scene for Hinduism’s survival in Sri Lanka. Shaivism (devotional worship of Lord Shiva) was the dominant branch practised by the Tamil peoples, thus most of the traditional Hindu temple architecture and philosophy of Sri Lanka drew heavily from this particular strand of Hinduism. Thirugnanasambanthar mentioned the names of several Sri Lankan Hindu temples in his works.[308]

Islam is the third most prevalent religion in the country, having first been brought to the island by Arab traders over the course of many centuries, starting around the mid or late 7th century CE. Most followers on the island today are Sunni who follow the Shafi’i school[309] and are believed to be descendants of Arab traders and the local women whom they married.[310]

Christianity reached the country at least as early as the fifth century (and possibly in the first),[311] gaining a wider foothold through Western colonists who began to arrive early in the 16th century.[312] Around 7.4% of the Sri Lankan population are Christians, of whom 82% are Roman Catholics who trace their religious heritage directly to the Portuguese. Tamil Catholics attribute their religious heritage to St. Francis Xavier as well as Portuguese missionaries. The remaining Christians are evenly split between the Anglican Church of Ceylon and other Protestant denominations.[313]

There is also a small population of Zoroastrian immigrants from India (Parsis) who settled in Ceylon during the period of British rule.[314] This community has steadily dwindled in recent years.[315]

Religion plays a prominent role in the life and culture of Sri Lankans. The Buddhist majority observe Poya Days each month according to the Lunar calendar, and Hindus and Muslims also observe their own holidays. In a 2008 Gallup poll, Sri Lanka was ranked the third most religious country in the world, with 99% of Sri Lankans saying religion was an important part of their daily life.[316]

Health

Development of life expectancy

Sri Lankans have a life expectancy of 75.5 years at birth, which is 10% higher than the world average.[259][258] The infant mortality rate stands at 8.5 per 1,000 births and the maternal mortality rate at 0.39 per 1,000 births, which is on par with figures from developed countries. The universal «pro-poor»[317] health care system adopted by the country has contributed much towards these figures.[318] Sri Lanka ranks first among southeast Asian countries with respect to deaths by suicide, with 33 deaths per 100,000 persons. According to the Department of Census and Statistics, poverty, destructive pastimes, and inability to cope with stressful situations are the main causes behind the high suicide rates.[319]

On 8 July 2020, the World Health Organization declared that Sri Lanka had successfully eliminated rubella and measles ahead of their 2023 target.[320]

Education

With a literacy rate of 92.9%,[259] Sri Lanka has one of the most literate populations amongst developing nations.[321] Its youth literacy rate stands at 98.8%,[322] computer literacy rate at 35%,[323] and primary school enrollment rate at over 99%.[324] An education system which dictates 9 years of compulsory schooling for every child is in place.

The free education system established in 1945[325] is a result of the initiative of C. W. W. Kannangara and A. Ratnayake.[326][327] It is one of the few countries in the world that provide universal free education from primary to tertiary stage.[328] Kannangara led the establishment of the Madhya Vidyalayas (central schools) in different parts of the country in order to provide education to Sri Lanka’s rural children.[323] In 1942, a special education committee proposed extensive reforms to establish an efficient and quality education system for the people. However, in the 1980s changes to this system separated the administration of schools between the central government and the provincial government. Thus the elite national schools are controlled directly by the ministry of education and the provincial schools by the provincial government. Sri Lanka has approximately 10,155 government schools, 120 private schools and 802 pirivenas.[259]

Sri Lanka has 17 public universities.[329][330] A lack of responsiveness of the education system to labour market requirements, disparities in access to quality education, lack of an effective linkage between secondary and tertiary education remain major challenges for the education sector.[331] A number of private, degree awarding institutions have emerged in recent times to fill in these gaps, yet the participation at tertiary level education remains at 5.1%.[332] Sri Lanka was ranked 95th in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, down from 89th in 2019.[333][334][335][336]

Science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke served as chancellor of Moratuwa University from 1979 to 2002.[337]

Human rights and media

The Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (formerly Radio Ceylon) is the oldest-running radio station in Asia,[338] established in 1923 by Edward Harper just three years after broadcasting began in Europe.[338] The station broadcasts services in Sinhala, Tamil, English and Hindi. Since the 1980s, many private radio stations have also been introduced. Broadcast television was introduced in 1979 when the Independent Television Network was launched. Initially, all television stations were state-controlled, but private television networks began broadcasting in 1992.[339]

As of 2020, 192 newspapers (122 Sinhala, 24 Tamil, 43 English, 3 multilingual) are published and 25 TV stations and 58 radio stations are in operation.[259] In recent years, freedom of the press in Sri Lanka has been alleged by media freedom groups to be amongst the poorest in democratic countries.[340] Alleged abuse of a newspaper editor by a senior government minister[341] achieved international notoriety because of the unsolved murder of the editor’s predecessor, Lasantha Wickrematunge,[342] who had been a critic of the government and had presaged his own death in a posthumously published article.[343]

Officially, the constitution of Sri Lanka guarantees human rights as ratified by the United Nations. However, several groups, such as Amnesty International, Freedom from Torture, Human Rights Watch,[344] as well as the British government[345] and the United States Department of State have criticised human rights violations in Sri Lanka.[346] The Sri Lankan Government and the LTTE have both been accused of violating human rights. A report by an advisory panel to the UN secretary-general accused both the LTTE and the Sri Lankan government of war crimes during final stages of the civil war.[347][348] Corruption remains a problem in Sri Lanka, and there is little protection for those who stand up against corruption.[349] The 135-year-old Article 365 of the Sri Lankan Penal Code criminalises gay sex, with a penalty of up to ten years in prison.[350]

The UN Human Rights Council has documented over 12,000 named individuals who have disappeared after detention by security forces in Sri Lanka, the second-highest figure in the world since the Working Group came into being in 1980.[351] The Sri Lankan government confirmed that 6,445 of these died. Allegations of human rights abuses have not ended with the close of the ethnic conflict.[352]

UN Human Rights Commissioner Navanethem Pillay visited Sri Lanka in May 2013. After her visit, she said: «The war may have ended [in Sri Lanka], but in the meantime, democracy has been undermined and the rule of law eroded.» Pillay spoke about the military’s increasing involvement in civilian life and reports of military land grabbing. She also said that, while in Sri Lanka, she had been allowed to go wherever she wanted, but that Sri Lankans who came to meet her were harassed and intimidated by security forces.[353][354]