Координаты: 46°48′00″ с. ш. 8°14′00″ в. д. / 46.8° с. ш. 8.233333° в. д. (G)

|

||||

|

||||

| Девиз: ««Unus pro omnibus omnes pro uno» лат. «Один за всех, все за одного»» | ||||

| Гимн: «Швейцарский псалм» | ||||

| Дата независимости | Провозглашена 1 августа 1291 Признана 24 октября 1648 Федерация с 1848 (от Федеративная хартия) |

|||

| Официальный язык | Немецкий, Французский, Итальянский, Романшский |

|||

| Столица | нет столицы в Швейцарии, условно Берн | |||

| Крупнейшие города | Цюрих, Женева, Базель, Берн, Лозанна | |||

| Форма правления | Парламентарная республика | |||

| Федеральный совет | Ханс-Рудольф Мерц (Президент Швейцарии) Мориц Лойенбергер, Ули Маурер, Мишлин Кальми-Ре, Паскаль Кушпен, Дорис Лойтхард (вице-президент), Эвелине Видмер-Шлумпф |

|||

| Территория • Всего • % водной поверхн. |

136-я в мире 41 284 км² 4,2 |

|||

| Население • Всего (2008) • Плотность |

94-е в мире 7 700 200 чел. 181,4 чел./км² |

|||

| ВВП • Итого (сентябрь 2008) • На душу населения |

36-й в мире $300,186 млрд. $40 000 |

|||

| Валюта | Швейцарский франк (CHF, код 756) |

|||

| Интернет-домен | Телефонный код | +41 | ||

| Часовой пояс | UTC +1 |

Швейца́рия (нем. die Schweiz, фр. la Suisse, итал. Svizzera, ром. Svizra), официальное название Швейца́рская конфедера́ция (нем. Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft, фр. Confédération suisse, итал. Confederazione Svizzera, ром. Confederaziun svizra) — небольшое, не имеющее выхода к морю государство в центральной Европе, граничащее на севере с Германией, на западе с Францией, на юге с Италией, на востоке с Австрией и Лихтенштейном. Название происходит от наименования кантона Швиц, образованного от древненемецкого «жечь».

Латинское название страны — Confoederatio Helvetica, это название встречается в аббревиатуре швейцарской валюты и в названии швейцарского интернет-домена (CH). На почтовых марках используется латинское название Helvetia, иногда употребляющееся в русском языке как название страны — Гельвеция.

Содержание

- 1 История

- 2 Политическое устройство

- 3 Административное деление

- 4 Географические данные

- 4.1 Климат

- 4.2 Рельеф

- 5 Экономика

- 5.1 Финансы

- 5.1.1 Налоги

- 5.2 Добывающая отрасль

- 5.3 Промышленность

- 5.4 Энергетика

- 5.5 Транспорт

- 5.6 Сельское хозяйство

- 5.7 Туризм

- 5.1 Финансы

- 6 Население

- 7 Религия

- 8 Внешняя политика Швейцарии

- 8.1 Шенгенское пространство

- 8.2 Международные организации

- 8.3 Швейцария и Организация Объединенных Наций

- 8.4 Отношения Швейцарии и ЕС

- 8.5 Отношения Швейцарской Конфедерации и России

- 8.6 Отношения Швейцарии и США в начале 21 века

- 8.7 Миграционная политика Швейцарии в XX — начале XXI вв

- 8.8 Беженцы и защита от преследования

- 9 Достопримечательности Швейцарии

- 9.1 Природные достопримечательности

- 9.2 Знаменитости, связанные со Швейцарией

- 9.2.1 Русская Швейцария

- 10 Культура Швейцарии

- 10.1 Спорт

- 10.2 Праздники

- 10.3 Национальная кухня Швейцарии

- 10.4 Часы работы заведений

- 11 Вооружённые силы

- 11.1 Сухопутные войска

- 12 Средства массовой информации Швейцарии

- 13 Библиография

- 14 Примечания

- 15 Ссылки

- 15.1 Политика

- 15.2 Информация

- 15.3 Туризм

- 15.4 Разное

История

Политическое устройство

Швейцария — федеративная республика. Действующая конституция принята в 1999. В ведении федеральных властей находятся вопросы войны и мира, внешних отношений, армии, железных дорог, связи, денежной эмиссии, утверждение федерального бюджета и т. д.

Швейцария была создана из объединения 3 кантонов. Глава страны — президент, избираемый каждый год по принципу ротации из числа членов Федерального совета.

Высший орган законодательной власти — двухпалатный парламент — Союзное собрание, состоящее из Национального совета и Совета кантонов (Палаты равноправные).

Национальный совет (200 депутатов) избирается населением на 4 года по системе пропорционального представительства.

Федеративное устройство и конституция Швейцарии были закреплены в конституциях 1848, 1874 и 1999 гг.

Сейчас Швейцария — федерация из 26 кантонов (20 кантонов и 6 полукантонов). До 1848 года (кроме короткого периода Гельветической республики) Швейцария представляла собой конфедерацию. Каждый кантон имеет свою конституцию, законы, но их права ограничены федеральной конституцией. Законодательная власть принадлежит Парламенту, а исполнительная — Федеральному совету (правительству).

В Совете кантонов 46 депутатов, которые избираются населением по мажоритарной системе относительного большинства в 20 двухмандатных округах и 6 одномандатных, то есть по 2 чел. от каждого кантона и по одному от полукантона на 4 года (в некоторых кантонах — на 3 года).

Все законы, принятые парламентом, могут быть утверждены или отвергнуты на всенародном (факультативном) референдуме (прямая демократия). Для этого после принятия закона в 100-дневный срок необходимо собрать 50 тыс. подписей.

Избирательное право предоставляется всем гражданам, достигшим 18 лет.

Высшая исполнительная власть принадлежит правительству — Федеральному совету, состоящему из 7 членов, каждый из которых возглавляет один из департаментов (министерств). Члены Федсовета избираются на совместном заседании обеих палат парламента. Все члены Федерального совета поочередно занимают посты президента и вице-президента.

Основы швейцарского государства были заложены в 1291. До конца XVIII века в стране не существовало центральных государственных органов, но периодически созывались общесоюзные соборы — тагзатцунг.

В 1798 в Швейцарию были введены французские войска, принята конституция по образцу французской.

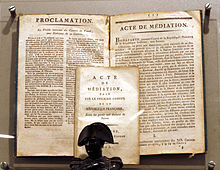

В 1803 году в рамках «Акта посредничества» Наполеон возвратил Швейцарии независимость.

В 1848 принята конституция, предусматривавшая создание двухпалатного федерального парламента.

В 1874 принята конституция, которая ввела институт референдумов.

В 1971 право голоса получили женщины.

В 1999 году была принята новая, основательно переработанная редакция этой конституции.

Состав парламента, избранного в 2003:

- Швейцарская народная партия (ШНП) — 8 мест в Совете кантонов и 55 в Национальном совете, в 2008 фракция включает членов Гражданской партии

- Социал-демократическая партия Швейцарии (СПШ) — 9 и 52 места

- Радикально-демократическая партия Швейцарии (либералы) — 14 и 36 мест,

- Христианско-демократическая народная партия — 15 и 28 мест.

Федеральный совет — Гражданская партия 2, Социал-демократическая партия 2, Радикально-демократическая партия −2, Христианско-демократическая партия 1

В октябре 2007 года прошли очередные парламентские выборы в стране. По их итогам правые националисты из Народной партии одерживают самую крупную победу на парламентских выборах страны с 1919 года.

Состав парламента по результатам выборов 2007 года:

- Швейцарская народная партия — 7 мест в Совете кантонов и 62 в Национальном совете;

- Социал-демократическая партия Швейцарии — 6 и 43 места;

- Христианско-демократическая народная партия- 11 и 31 место;

- Радикально-демократическая партия Швейцарии — 9 и 31 место;

Интересно, что наибольшее число голосов Народная партия набрала в кантоне Швиц (44,9 %), а наименьшее — в Тичино (8,7 %). При этом наибольшая активность граждан наблюдалась в кантоне Шаффгаузен (явка составила более 65 % населения), наименьшая — в Аппенцелль-Иннерроден (лишь 21 %).

Председатель Совета кантонов (2006) — Рольф Бютикер (либерал). Председатель Совета Кантонов (2009) — Ален Берсе. Председатель Национального совета (2006) — Клоп Яниак (СПШ).

Председатель Верховного суда (2007) — Артур Эшлиманн.

Все кантоны имеют свои конституции; законодательная и исполнительная власть принадлежит большим советам (парламентам) и кантональным советам (правительствам), избираемым гражданами на срок от 1 до 5 лет. В округах (возглавляются префектом, назначаемым кантональным советом) и общинах избираются органы самоуправления — общие собрания граждан — «ландсгемайнде» (в немецких кантонах) и общинные советы (во французских кантонах). Исполнительными органами в общинах являются муниципалитеты или малые советы, возглавляемые мэрами или синдиками.

Швейцария имеет давние традиции политического и военного нейтралитета, однако принимает деятельное участие в международном сотрудничестве и на её территории находятся многие международные организации.

Есть несколько взглядов на время возникновения швейцарского нейтралитета. По мнению некоторых учёных, Швейцария начала придерживаться статуса нейтралитета после заключения мирного договора с Францией 29 ноября 1516 года, в котором был провозглашён «вечный мир». В дальнейшем швейцарские власти приняли ряд решений, которые продвинули страну на пути к определению своего нейтралитета. В 1713 году нейтралитет страны был признан Францией, Испанией, Нидерландами и Англией, заключившими Утрехтский мир. Однако в 1798 году Швейцария заключила с наполеоновской Францией договор, в соответствии с которым страна обязывалась предоставить свою территорию для ведения военных действий, а также выставить военный корпус. На Венском конгрессе в 1815 году был закреплён «вечный нейтралитет» Швейцарии. Окончательно нейтралитет подтверждён и конкретизирован Гарантийным актом, подписанным в Париже 20 ноября 1815 года Австрией, Великобританией, Португалией, Пруссией, Россией и Францией.

Административное деление

административное деление Швейцарии

Швейцария — федеративная республика, состоящая из 23 кантонов, 3 из которых (Унтервальден, Базель и Аппенцелль) делятся на полукантоны. Ниже — список кантонов (стоить заметить, что немало городов Швейцарии имеют разные названия, употребляемые на разных языках страны).

| Кантон | Крупнейший город | Площадь, тыс. км² |

|---|---|---|

| Цюрих (Zürich) | Цюрих (Zürich) | 1,7 |

| Берн (Bern) | Берн (Bern) | 5,9 |

| Люцерн (Luzern) | Люцерн (Luzern) | 1,5 |

| Ури (Uri) | Альтдорф (Altdorf) | 1,1 |

| Швиц (Schwyz) | Швиц (Schwyz) | 0,9 |

| Унтервальден (Unterwalden) | ||

| Обвальден (Obwalden)1 | Зарнен (Sarnen) | 0,5 |

| Нидвальден (Nidwalden)1 | Штанс (Stans) | 0,3 |

| Гларус (Glarus) | Гларус (Glarus) | 0,7 |

| Цуг (Zug) | Цуг (Zug) | 0,2 |

| Фрибур (Fribourg) | Фрибур (Fribourg) | 1,7 |

| Золотурн (Solothurn) | Золотурн (Solothurn) | 0,8 |

| Базель (Basel) | ||

| Базель-Штадт (Basel-Stadt)1 | Базель (Basel) | 0,04 |

| Базель-Ланд (Basel-Land)1 | Листаль (Liestal) | 0,4 |

| Шаффгаузен (Schaffhausen) | Шаффхаузен (Schaffhausen) | 0,3 |

| Аппенцелль (Appenzell) | ||

| Аппенцелль — Ауссерроден (Appenzell-Ausserrhoden)1 | Херизау (Herisau) | 0,2 |

| Аппенцелль — Иннерроден (Appenzell-Innerrhoden)1 | Аппенцелль (Appenzell) | 0,2 |

| Санкт-Галлен (St. Gallen) | Санкт-Галлен (St. Gallen) | 2,0 |

| Граубюнден (Graubunden) | Кур (Chur) | 7,1 |

| Ааргау (Aargau) | Аарау (Aarau) | 1,4 |

| Тургау (Thurgau) | Фрауэнфельд (Frauenfeld) | 1,0 |

| Тичино (Ticino) | Беллинцона (Bellinzona) | 2,8 |

| Во (фр. Vaud) | Лозанна (фр. Lausanne) | 3,2 |

| Вале (Valais) | Сьон (Sion) | 5,2 |

| Нёвшатель (фр. Neuchâtel) | Нёвшатель (фр. Neuchâtel) | 0,8 |

| Женева (фр. Genève) | Женева (фр. Genève) | 0,3 |

| Юра (фр. Jura)² | Делемон (Delemont), нем. Дельсберг (Delsberg) | 0,8 |

1 Полукантоны — в реальности полноценные кантоны.

² Образовался в 1979 году.

Географические данные

Территория Швейцарии. Снимок со спутника

Швейцария — страна без выхода к морю, территория которой делится на три природных региона:

- Горы Юра на севере,

- Швейцарское плато в центре,

- Горы Альпы на юге, занимающие 61 % всей территории Швейцарии.

Северная граница частично проходит по Боденскому озеру и Рейну, который начинается в центре Швейцарских Альп и образует часть восточной границы. Западная граница проходит по горам Юра, южная- по Итальянским Альпам и Женевскому озеру.

Плато лежит в низине, но большая его часть расположена выше 500 метров над уровнем моря. Состоящие из лесистых хребтов (до 1600 м) молодые складчатые горы Юра протянулись на территорию Франции и Германии. Наивысшая точка Швейцарии находится в Альпах — пик Дюфур(4634 м.), наинизшая — озеро Лаго-Маджоре — 193 м.

Самые крупные реки — Рона, Рейн, Лиммат, Ааре.

Около 25 % территории Швейцарии покрыто лесами — не только в горах, но и в долинах, и на некоторых плоскогорьях. Древесина является важным сырьём и источником топлива.

Швейцария богата озёрами. Швейцария знаменита своими озерами, наиболее привлекательные из них расположены по краям Швейцарского плато — Женевское, Фирвальдштетское, Тунское на юге, Цюрихское на востоке, Бильское и Невшательское на севере. Большинство из них имеет ледниковое происхождение: они образовались во времена, когда крупные ледники спускались с гор на Швейцарское плато. К югу от оси Альп в кантоне Тичино расположены озера Лаго-Маджоре и Лугане.

Десять крупнейших озёр Швейцарии:

- Женевское озеро (582,4 км²)

- Боденское озеро (539 км²)

- Нёвшательское озеро (217,9 км²)

- Лаго-Маджоре (212,3 км²)

- Фирвальдштетское озеро (113,8 км²)

- Цюрихское озеро (88,4 км²)

- Лугано (48,8 км²)

- Тун (48,4 км²)

- Бильское озеро (40 км²)

- Цугское озеро (38 км²)

Климат

В Швейцарии преобладает континентальный климат, типичный для Центральной Европы, со значительными колебаниями в зависимости от высоты над уровнем моря. На Западе страны велико влияние Атлантического океана, по мере продвижения на Восток и в горных районах климат приобретает черты континентального. Зимы холодные, на плато и в долинах температура достигает нуля, а в горных районах −10 °C и ниже. Средняя температура летом в низинах — +18-20°C, несколько ниже в горах. В Женеве средние температуры июля около 19 °C, января примерно 19 °C. За год выпадает около 850 мм осадков. Особенность-сильные северные и южные ветры. Годовой уровень осадков в Цюрихе на плато составляет 100 мм, а в Зенте — более 200 мм. Значительная часть осадков выпадает зимой в виде снега. Некоторые районы постоянно находятся под слоем льда . Особым качеством восточных Альп является то, что около 65 % количества годовых осадков выпадает в виде снега. Нередко даже в мае-июне, на высоте больше 1.500 м выпадают осадки в виде снежной крупы. Швейцарский климат необычен тем, что для каждой области Швейцарии свойственен свой пейзаж, свой климат. Именно здесь Арктика соседствует с тропиками. Здесь можно обнаружить, как в Арктике, мхи и лишайники, а так же пальмы и мимозы, — по существу как на побережье Средиземного моря.

Рельеф

Большая часть страны расположена на территории Альп. На юге находятся Пеннинские Альпы (высота до 4634 м -пик Дюфур, высшая точка Швейцарии), Лепонтинские Альпы, Ретийские Альпы и массив Бернина. Глубокими продольными долинами Верхней Роны и Переднего Рейна Пеннинские и Лепонтинские Альпы отделены от Бернских Альп(г. Финстераархорн, высота до 4274 м) и Гларнских Альп, образующих систему хребтов, вытянутых с юго-запада на северо-восток через всю страну. Преобладают островерхие хребты, сложенные преимущественно кристаллическими породами и сильно расчленённые эрозией; многочисленны ледники и ледниковые формы рельефа. Основные перевалы (Большой Сен-Бернар, Симплон, Сен-Готард, Бернина) расположены выше 2000 м. Для ландшафта горной Швейцарии характерно большое количество ледников и ледниковых форм рельефа, общая площадь оледенения — 1950 кв.км. Всего в Швейцарии насчитывается примерно 140 крупных долинных ледников (Алечский глетчер и другие), есть также каровые и висячие ледники.

Экономика

- Основные статьи импорта: промышленное и электронное оборудование, продукты питания, чугун и сталь, нефтепродукты.

- Основные статьи экспорта: машины, часы, текстиль, медикаменты, электрическое оборудование, органические химикаты.

Преимущества: высококвалифицированная рабочая сила, надежная сфера услуг. Развитые отрасли машиностроения и высокоточной механики. Транснациональные концерны химпрома, фармакологии и банковского сектора. Банковская тайна привлекает иностранный капитал. Банковский сектор составляет 9 % ВВП. Инновации в массовых рынках (часы Swatch, концепция автомобилей Swatch).

Слабые стороны: сверхдорогие товары из-за картельного протекционизма. Сильно субвенционируемое сельское хозяйство.

Швейцария одна из самых развитых и богатых стран мира. Швейцария — высокоразвитая индустриальная страна с интенсивным высокопродуктивным сельским хозяйством и почти полным отсутствием каких-либо полезных ископаемых. По подсчетам западных экономистов, она входит в первую десятку стран мира по уровню конкурентоспособности экономики. Швейцарская экономика тесно связана с внешним миром, прежде всего со странами ЕС, тысячами нитей производственной кооперации и внешнеторговых сделок. Ок. 80-85 % товарооборота Швейцарии приходится на государства ЕС. Через Швейцарию транзитом проходит более 50 % всех грузов из северной части Западной Европы на юг и в обратном направлении. После заметного роста в 1998—2000 гг. экономика страны вступила в полосу спада. В 2002 г. ВВП вырос на 0,5 % и составил 417 млрд шв. фр. Инфляция была на отметке 0,6 %. Уровень безработицы достиг 3,3 %. В экономике занято ок. 4 млн человек (57 % населения), из них: в промышленности — 25,8 %, в том числе в машиностроении — 2,7 %, в химической промышленности — 1,7 %, в сельском и лесном хозяйстве — 4,1 %, в сфере услуг — 70,1 %, в том числе в торговле — 16,4 %, в банковском и страховом деле — 5,5 %, в гостинично-ресторанном бизнесе — 6,0 %. Политика нейтралитета позволила избежать разрухи двух мировых войн.

Финансы

Швейцария — богатейшая страна мира и один из важнейших банковских и финансовых центров мира (Цюрих — третий после Нью-Йорка и Лондона мировой валютный рынок). Швейцарская Конфедерация входит в список офшорных зон. В стране функционирует около 4 тыс. финансовых институтов, в том числе множество филиалов иностранных банков. На швейцарские банки приходится 35-40 % мирового управления собственностью и имуществом частных и юридических лиц. Они пользуются хорошей репутацией у клиентов благодаря стабильной внутриполитической обстановке, твердой швейцарской валюте, соблюдению принципа «банковской тайны». Швейцария, являясь крупным экспортером капитала, занимает четвёртое место в мире после США, Японии, ФРГ. Прямые инвестиции за границей составляют 29 % швейцарского ВВП (средний показатель в мире — ок. 8 %). 75 % всех швейцарских инвестиций направляется на развитые промышленности, среди развивающихся стран наиболее привлекают швейцарские капиталы Латинская Америка и ЮВА. Доля Восточной Европы в общем объёме инвестиций пока что незначительна.

1 апреля 1998 г. в Швейцарии вступил в силу федеральный закон о борьбе с «отмыванием» денег в финансовом секторе, позволивший несколько приподнять завесу банковской тайны в целях выявления «грязных» денег.

В 1815 году Венский конгресс принял гарантии нейтралитета Швейцарии. С тех пор она не участвовала ни в одной войне и её банки никогда не подвергались разграблению. Впрочем, ещё при Людовике Шестнадцатом один из швейцарских банкиров — Жак Неккер — был настолько авторитетен, что стал первым лицом финансового ведомства Франции.

Аргумент в пользу надежности швейцарских банков прост — они не могут разориться, поскольку не участвуют в рискованных финансовых операциях. Именно в Швейцарии возникли первые частные банки. Сегодня их в стране более 400. Конфиденциальность сведений швейцарские банки гарантируют согласно государственному закону о банковской тайне, принятому в 1713 году. Швейцарцы даже отказались выдать французскому правительству информацию о переводах со счета гражданина Швейцарии Йеслама Бен Ладена — единокровного брата «террориста номер один».

В 2006 году банк «Кантональ» провел ревизию невостребованных вкладов и обнаружил незакрытый счет на имя Владимира Ульянова, на котором лежит всего 13 франков — 286 рублей. Зато, по данным Министерства иностранных дел Великобритании, в швейцарских банках до сих пор хранится золото нацистов на сумму 4 миллиарда долларов.

Глава Швейцарской банковской ассоциации — Урс Ротт.

Налоги

Прибыль компаний — резидентов Швейцарии, включая полученные дивиденды, проценты, роялти, а также прибыль от реализации внеоборотных активов подлежит обложению корпоративным налогом. Уточним, компания признается налоговым резидентом Швейцарии, если она учреждена в этом государстве, имеет постоянное представительство или эффективно управляется и контролируется из Швейцарии. В целом налоговая база швейцарского корпоративного налога формируется по правилам, аналогичным российским. То есть доходы компании уменьшаются на сумму обоснованных расходов.

Ставка корпоративного налога состоит из двух частей. Федеральная часть взимается по единой ставке 8,5 процентов. Однако, в соответствии с существующими правилами, налог не исчисляется с прибыли, а извлекается из нее. Поэтому эффективная налоговая ставка составляет 7,83 процента.

Кантональные или муниципальные ставки варьируются в каждом отдельном кантоне. Самые низкие региональные ставки корпоративного налога установили кантоны Аппенцелль-Аусерроден и Обвальден — 6 процентов. Таким образом, можно говорить, что совокупная эффективная ставка корпоративного налога в Швейцарии варьируется от 12,7 (100 % : (100 % + 8,5 % + 6 %) х (8,5 % + 6 %)) до 24,2 процента в зависимости от кантона и муниципалитета нахождения налогоплательщика. Среднее значение в 2008 году составило 19,2 процента.

См. подробно А. С. Захаров «Как экономят, используя льготные налоговые режимы Швейцарии», журнал Практическое налоговое планирование, январь 2009

Добывающая отрасль

В Швейцарии мало полезных ископаемых. Промышленное значение имеют каменная соль и стройматериалы.

Промышленность

В промышленности доминируют крупные объединения транснационального характера, как правило, успешно выдерживающие конкуренцию на мировом рынке и занимающие на нём ведущие позиции: концерны «Нестле» (пищевые продукты, фармацевтические и косметические изделия, детское питание), «АББ — «Асеа Браун Бовери» (электротехника и турбиностроение). Швейцарию часто ассоциируют с часовой фабрикой мира. В опоре на старые традиции и высокую техническую культуру здесь производят часы самых престижных марок.

Энергетика

Около 42 % электроэнергии в Швейцарии вырабатывается на АЭС, 50 % на ГЭС, а остальные 8 % на ТЭС из импортируемой нефти. Большинство ГЭС находится в Альпах, где создано более 40 искусственных озёр — водохранилищ. По инициативе «зеленых» строительство новых АЭС временно прекращено, однако в перспективе Швейцария не собирается пока сворачивать программу атомной энергетики.

Транспорт

Швейцарская транспортная система «отлажена, как часы». Из 5031 км железнодорожных путей электрифицировано более половины. В горах проложено более 600 туннелей, включая Симплонский (19,8 км.). В горных регионах работают фуникулёры и канатные дороги. Протяжённость дорог — около 71 тыс. км. Важную роль играют дороги, проходящие через горные перевалы Сен-Готард, Сен-Бернар и другие.

27 октября 2008 в Швейцарии было официально открыто первое метро — 5,9 км, 14 станций.

Основные международные аэропорты — Женева, Цюрих, Базель.

Сельское хозяйство

Сельское хозяйство имеет ярко выраженную животноводческую направленность (с упором на производство мясомолочной продукции), отличается высокой урожайностью и производительностью труда. Характерно преобладание мелких хозяйств. Швейцарский сыр уже не одно столетие хорошо известен во многих странах мира. В целом сельское хозяйство обеспечивает потребности страны в продуктах питания на 56-57 %. Швейцария поддерживает внешнеторговые связи практически со всеми странами мира. Экономика страны в значительной степени зависит от внешней торговли — как в импорте сырья и полуфабрикатов, так и в экспорте изделий промышленности (на экспорт идет более 50 % продукции текстильной, около 70 % машиностроительной, свыше 90 % химической и фармацевтической, 98 % часовой промышленности). На развитые индустриальные страны приходится 80 % оборота внешней торговли Швейцарии. Основными её партнерами являются страны ЕС — св.3/4 экспорта и импорта. Среди крупнейших внешнеторговых партнеров — ФРГ, Франция, США, Италия, Великобритания, страны Бенилюкса.

Туризм

Иностранный туризм. Являясь традиционной страной туризма, Швейцария удерживает в этой сфере прочные позиции в Европе. Наличие развитой туристической инфраструктуры, сети железных и автомобильных дорог в сочетании с живописной природой и выгодным географическим положением обеспечивает приток в страну значительного количества туристов, прежде всего немцев, американцев, японцев, а в последние годы также русских, индийцев, китайцев.

15 % национального дохода поступает за счёт туризма. MOII Пожалуй, самыми известными курортами в Швейцарии являются Давос, Сент-Моритц, Церматт, и Интерлакен остаются очень популярными местами из тех, где наши соотечественники отдыхают и развлекаются зимой.

Население

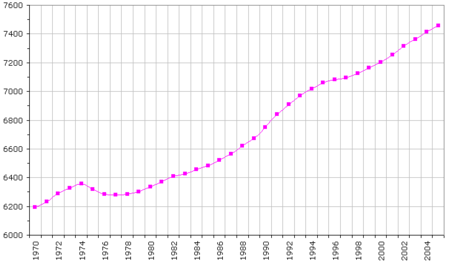

Динамика численности населения Швейцарии с 1970 по 2005 г.г. Число жителей в тыс. чел.

Общая численность населения по оценкам 2008 года составляет 7 580 000 чел. Возрастная структура населения: 0-14 лет: 15,8 % 15-64 года: 68,2 % старше 65 лет: 16 %

Средний возраст населения: средний: 40,7 мужчины: 39,6 женщины: 41,7

Этнический состав: немцы (65 %), французы (18 %), итальянцы (10 %), другие национальности (7 %). Уровень грамотности населения-99 %.

Уровень жизни в Швейцарии очень высок, однако социальное законодательство совершенствуется медленно. Так, лишь в 1983 г. в стране введен трехнедельный оплачиваемый отпуск. Разница в оплате труда мужчин и женщин все ещё достигает 30 %. Средний уровень заработной платы в Швейцарии — 5400 шв. фр. в месяц, средний доход на семью из трех человек — ок. 100 тыс. шв. фр. в год. Следует учитывать при этом, что средний уровень цен в Швейцарии, как правило, на 30-50 % выше, чем в странах ЕС.

Религия

В эпоху Реформации Швейцария пережила церковный раскол. Религиозные разногласия будоражили страну вплоть до середины XIX в., сказавшись на формировании единого государства. Кантоны в зависимости от вероисповедания создавали альянсы и союзы, вели между собой войны. Мир воцарился окончательно в 1848 г. В настоящее время протестанты составляют около 48 % населения, католики — примерно 50 %. Конфессиональные различия в Швейцарии не всегда совпадают с лингвистическими границами. Среди протестантов можно обнаружить и франкоязычных кальвинистов, и немецкоязычных последователей Цвингли. Центры немецкоязычного протестантизма — Цюрих, Берн и Аппенцелль. Большинство франкоязычных протестантов проживает в кантоне Женева и соседних кантонах Во и Невшатель. Католики преобладают в центральной Швейцарии вокруг города Люцерн, на большей части территории франкоязычных кантонов Фрибур и Вале и в италоязычном кантоне Тичино. Небольшие еврейские общины имеются в Цюрихе, Базеле и Женеве.

Внешняя политика Швейцарии

Внешняя политика Швейцарии согласно конституции этой страны строится с учетом международно-правового статуса постоянного нейтралитета. Начало швейцарской политики нейтралитета трудно связать с какой-либо определенной датой. Швейцарский историк Эдгар Бонжур по этому поводу сказал: «Понятие швейцарского нейтралитета возникло одновременно с понятием швейцарской нации». Небезынтересно отметить, что еще в 14 веке в договорах отдельных кантонов, составивших впоследствии Швейцарскую конфедерацию, с их соседями употребляется немецкий термин «stillsitzen» (буквально «сидеть смирно»), что примерно соответствует позднейшему понятию нейтралитета. Постоянный нейтралитет Швейцарии возник в результате подписания четырех международно-правовых актов: Акта Венского Конгресса от 8(20) марта 1815 года, Приложения к Акту Венского Конгресса № 90 от 8(20) марта 1815 г., Декларации держав о делах Гельветического Союза и Акта относительно признания и гарантии постоянного нейтралитета Швейцарии и неприкосновенности ее территории. В отличие от других стран, избравших подобный путь исключительно под воздействием внешних факторов (например, как результат поражения в войне), нейтралитет Швейцарии сформировался и по внутриполитическим причинам: нейтралитет, став объединяющей нацию идеей, способствовал эволюции её государственности от аморфной конфедерации к централизованному федеративному устройству. За годы политики постоянного вооруженного нейтралитета альпийской республике удалось избежать участия в двух опустошительных мировых войнах и укрепить свой международный авторитет, в том числе путем осуществления многочисленных посреднических усилий. Принцип поддержания связей «между странами, а не между правительствами» позволял вести диалог со всеми, вне зависимости от политических или идеологических соображений. Швейцария представляет третьи государства там, где у них прерваны дипломатические отношения (к примеру, интересы СССР в Ираке в 1955 году, Великобритании в Аргентине во время англо-аргентинского конфликта 1982 года; в настоящее время Швейцария представляет интересы США на Кубе и в Иране, интересы Кубы в США, интересы Российской Федерации в Грузии после разрыва дипломатических отношений между этими странами в 2008 г.). Швейцария оказывает «добрые услуги», предоставляя свою территорию для прямых переговоров между участниками конфликтов (нагорно-карабахская, абхазская и южноосетинские проблемы, кипрское урегулирование и т. д.). Из всех существующих в современном мире видов нейтралитета швейцарский — наиболее длительный и последовательный. Сегодня Швейцарская Конфедерация не входит ни в один военный альянс, ни в ЕС. В последние годы, в связи с переменами в Европе и мире, в правительстве и общественном мнении набирает силу настрой в пользу усиления интеграции с ЕС и более гибкой трактовки принципа нейтралитета. В мае 2004 г. подписан «второй пакет» секторальных договоров ЕС-Швейцария, который, вместе с «первым пакетом» (вступил в силу 1 июня 2002 г.), является своего рода альтернативой вступлению Швейцарии в ЕС. В рамках общенациональных референдумов, прошедших в 2005 году, народом Швейцарии положительно решен вопрос о присоединении Швейцарии к Шенгенскому и Дублинскому договорам (соглашение об этом с ЕС входит во «второй пакет»), а также о распространении положений Договора о свободе перемещений между Швейцарией и ЕС (входит в «первый пакет» секторальных договоров) на новых членов ЕС, вступивших в Союз в 2004 году. Вместе с тем, принято решение считать вопрос о вступлении Швейцарии в Евросоюз не «стратегической целью», как раньше, а только «политической опцией», то есть возможностью. В 1959 году Швейцария стала одной из стран-учредительниц ЕАСТ, в 1972 г. вошла в Европейское экономическое пространство, в 2002 г. — в ООН. Швейцария активно оказывает гуманитарную помощь жертвам конфликтов, содействует экономическому развитию стран третьего мира для преодоления нищеты. Швейцария поддерживает дипломатические отношения с Российской Федерацией. Дипломатические отношения между Швейцарией и РСФСР существовали с мая — по ноябрь 1918 г., затем были прерваны и восстановлены уже с СССР лишь 18 марта 1946 г.

Шенгенское пространство

19 мая 2004 года Швейцария подписала договор «О присоединении Швейцарии к Шенгенскому и Дублинскому соглашениям». С декабря 2008 года Швейцария является частью Шенгенского пространства, признает шенгенские визы и выдает такие визы сама. Став членом Шенгенского пространства, Швейцария получает доступ к «SIS» — «шенгенскому» электронному банку данных ЕС. Отменяется систематический контроль на внутренних границах стран Шенгенского соглашения, в том числе на границах Швейцарии с Германией, Италией, Францией, Австрией. У Швейцарии, однако, остаётся право осуществлять мобильный выборочный контроль во внутренних областях страны. В настоящее время Швейцария фактически находится в «шенгенском режиме», поскольку проконтролировать 700 тыс. переходов границы, совершающихся каждый день, физически невозможно. Что касается грузов, то Швейцария, не являясь членом Европейского таможенного союза, имеет право проводить их пограничный досмотр.

Международные организации

На территории Швейцарии более века действуют многочисленные международные организации. (около 250)

К настоящему времени, 22 международных организаций имеют штаб-квартиры в Женеве, 2 в Берне и 1 в Базеле. Кроме того, с 6 квази-межправительственными организациями заключены фискальные соглашения, и более чем 200 неправительственных организаций-советников ООН базируются в Швейцарии. [1] (англ.)

В Женеве:

- Европейское Отделение ООН,

- Европейская экономическая комиссия ООН,

- Экономический и социальный совет ООН,

- Конференция ООН по торговле и развитию,

- Всемирная организация здравоохранения,

- Международная организация труда,

- Международный союз электросвязи,

- Всемирная метеорологическая организация,

- Межпарламентский союз,

- Международный Комитет Красного Креста,

- Всемирный совет церквей,

- Всемирная торговая организация,

- Всемирная организация интеллектуальной собственности,

- Всемирная организация скаутского движения,

в Берне:

- Всемирный почтовый союз,

- Бюро международной организации пассажирских и грузовых железнодорожных перевозок,

- Европейская организация по контролю качества,

в Базеле:

- Банк международных расчетов,

- Международное общество по внутренней медицине,

в Лозанне:

- Международный олимпийский комитет,

- Международный комитет исторических наук.

Швейцария и Организация Объединенных Наций

ООН — одна из самых влиятельных организаций в мире. С ней у Швейцарии на протяжении более 50 лет складывались непростые, во многом противоречивые отношения. Новые веяния нового века внесли коррективы в характер этих взаимоотношений. Следует отметить, что поначалу Швейцария считалась государством-попутчиком гитлеровской Германии, поэтому ее вступление в ООН было невозможным. В марте 1945 года французское правительство выдвинуло идею относительно того, чтобы сделать ООН «открытой для всех миролюбивых государств», при этом заметив, что «обязанности, которые налагает на государство членство в ООН, не совместимы с принципами нейтралитета». Да и сама Швейцария долгое время особо не стремилась вступить в Организацию Объединенных Наций. Однако постепенно стала более серьезно осмысливаться необходимость преодоления внешнеполитической изоляции страны. По этой причине были предприняты попытки вступить в ряды ООН при сохранении нейтрального статуса в рамках организации, которые однако не принесли ожидаемого результата. Председатель ГА ООН, бельгийский министр иностранных дел П. А. Шпаак, попросил швейцарцев «не затрагивать более темы нейтралитета», так как это «создало бы опасный прецедент, который дал бы возможность и другим странам требовать себе исключений в плане взятия на себя обязательств, вытекающих из Устава ООН».

Проводя активную закулисную дипломатическую деятельность, Федеральные совет не решился развернуть обширную дискуссию по проблеме присоединения к ООН. Швейцарский историк Тобиас Кестли считает, что «Федеральный совет боялся общественной дискуссии». И.Петров, развивая его мысль, приходит к выводу, что причина этого страха крылась в нежелании разрушать сложившуюся в годы войны «атмосферу общественного единства» . Это было еще более нежелательно в условиях разгара «холодной войны». Правительство Швейцарии интенсифицировало усилия по созданию необходимых условий для вступления в ООН лишь тогда, когда в 1989 году на Европейском континенте и в мире в целом начали происходить известные политические перемены. Особенной активности эти усилия достигли именно в конце 90-х годов — начале XXI века, когда были составлены «Доклад об отношениях Швейцарии и Организации Объединенных Наций» 1998 года, «Внешнеполитический доклад за 2000 год», «Послание о народной инициативе к вхождению Швейцарии в Организацию Объединенных Наций» 2000 года. Выступая на церемонии вступления Швейцарии в ООН, К.Филлигер (в то время швейцарский президент) обозначил основные приоритеты, которыми Швейцария намерена руководствоваться в рамках ООН, подчеркнув, что «цели Устава Организации Объединенных Наций практически полностью совпадают с основными приоритетами внешней политики Швейцарии, поэтому полноправное членство в ООН внесет существенный вклад в достижение швейцарских целей на международной арене как в двустороннем, так и многостороннем формате». Среди приоритетов были названы такие проблемные области, как укрепление мира и безопасности, разоружение, международное право, права человека, помощь развивающимся странам, экологическое досье.

Напомним, что 3 марта 2002 года на референдуме народ Швейцарии проголосовал за вхождение в ООН. 11 марта 2002 года Швейцария стала полноправным членом Организации Объединенных Наций. 57-я Генассамблея ООН была первой, в которой участвовала Швейцария в качестве полноправного члена ООН. Среди швейцарских приоритетов здесь важную роль играл вопрос совершенствования механизма «прицельных санкций». Признавая необходимость такого инструмента международного воздействия, как санкции, Швейцария призывала однако к только таким санкциям и такому порядку их применения, при котором они, по возможности, затрагивали бы исключительно тех, кто реально ответственен за возникновение приведшего к введению санкций кризиса, не принося при этом вреда гражданскому населению или третьим странам. Среди возможных санкций подобного рода Швейцария выделяет замораживание счетов, введение эмбарго на поставки определенных видов товаров (оружие, нефть, алмазы, другие природные ресурсы), ограничения в области виз и перемещений частных и официальных лиц. По мнению самой Швейцарии, вхождение ее в ООН придало ее усилиям в области оптимизации порядка применения санкций дополнительный вес и убедительность.

В качестве полноправного члена ООН Швейцария активно работала в «Первом комитете» ГА ООН, занимающимся вопросами режима нераспространения и контроля за вооружениями. Швейцария решительно выступила за полную реализацию «тринадцати практических мер», принятых в 2000 году на Конференции по имплементации положений «Договора о нераспространении ядерного оружия». Швейцария призвала страны, которые еще не являются членами «Договора о запрещении ядерных испытаний», присоединиться к этому документу, а также присоединиться к переговорам по «Договору о запрещении производства расщепляющихся материалов военного назначения».

Еще одно приоритетное направление швейцарской политики в рамках ООН — контроль за торговлей оружием. Швейцария придает большое значение расширению сферы действия Соглашения 1980 г. о некоторых видах обычных вооружений («CWW»). Страна поддержала соответствующую резолюцию ООН относительно обычных вооружений и подчеркнула важность работы спецуполномоченного генерального секретаря ООН О.Оттуну по проблеме участия детей в вооруженных конфликтах. Швейцария выступила за универсализацию Оттавского договора по противопехотным минам . Со своей стороны Швейцария финансирует работу Международного гуманитарного противоминного центра в Женеве, который является важнейшим партнером ООН в сфере реализации противоминной программы («UNMAS»). Швейцария активно поддерживает создание и работу исследовательских программ и институтов в сфере безопасности. Так, в сотрудничестве с секретариатом ООН Швейцария выступила создателем «Гарвардской программы гуманитарной политики и конфликтных исследований». Швейцария активно сотрудничает и с другими академическими партнерами, например, с нью-йоркской «Международной Академией мира». Борьба с бедностью — еще один важный вектор в сфере деятельности Швейцарии в рамках ООН. Так, в ходе обсуждения результатов прошедшей в марте 2002 года в г. Монтеррей (Мексика) Международной конференции по вопросам финансирования политики в области развития, Швейцария призвала к более тесному и систематическому сотрудничеству всех заинтересованных стран и структур (в первую очередь имелись в виду ООН, Всемирный банк, Международный валютный фонд, ВТО, частные фирмы и неправительственные организации) в области развития стран «третьего мира» и борьбы с глобальной бедностью, выступив с инициативой по интенсификации диалога между Всемирным экономическим форумом в Давосе и ООН. Швейцария придает весомое значение проблематике развития горных регионов планеты. В декабре 2001 года Швейцария выступила в Нью-Йорке с инициативой проведения в 2002 году международного года гор (который и был проведен). В рамках 57-й сессии ГА ООН Швейцария активно выступала, с использованием потенциала «Группы по горной проблематике», в пользу обеспечения устойчивого развития горных районов Земли. В результате была принята соответствующая резолюция, которая была с удовлетворением воспринята швейцарцами «как документ, обеспечивающий политическую зримость проблемы развития горных регионов». На основании этой резолюции был учрежден Международный день гор — 11 декабря. Борьба за права человека — традиционная составная часть швейцарской внешней политики. На основании таких позиций Швейцария строит свою работу и в структурах ООН.

На 57-й сессии ГА ООН Швейцария активно выступала в рамках дебатов по проблематике, связанной с борьбой против наркомании и неконтролируемого распространения наркотических и приравненных к ним средств. Швейцария является участником «Единой конвенции ООН по наркосодержащим средствам» 1961 года, «Психотропной конвенции ООН» 1971 года и «Дополнительного протокола к Психотропной конвенции» 1972 года. Швейцарии является одним из главных спонсоров «Программы ООН по международному наркоконтролю». В 1998—2002 гг. Швейцария состояла членом «Комиссии ООН по наркосодержащим средствам». Швейцария особое внимание уделяет роли частного сектора экономики в обеспечении устойчивого поступательного развития мирового хозяйства и достижении всеобщего благосостояния. В частности, участвуя в дебатах на 57-й сессии ГА ООН, Швейцария подчеркивала важность тезиса о «социальной ответственности предпринимателей как на национальном, так и на международной уровне».

Швейцария использует возможности, открывшиеся перед ней как перед полноправным членом ООН, для дальнейшего продвижения своей экологической политики. Рассматривая Экологическую программу ООН в качестве важнейшей «опоры мировой экологической архитектуры», Швейцария последовательно выступает за усиление роли этой структуры, которая является «эффективным инструментом реализации принимаемых в экологической сфере решений». Еще с 57-й сессии ГА ООН Швейцария настойчиво следует тезису о том, что «между целями защиты окружающей среды и выгодами международной торговли нет и не может быть иерархических отношений, они одинаково важны, должны дополнять друг друга и быть соблюдены в равной степени». Здесь ее позиция соответствует, в частности, позиции Норвегии, оппонируя подходам США и некоторых развивающихся стран, оценивающие экологические цели как факторы, играющие подчиненную роль по отношению к резонам международной торговли.

Отношения Швейцарии и ЕС

Швейцарская конфедерация до середины XIX в. считалась одной из беднейших европейских стран. Ее население состояло из многих народов различного этнического, культурного, религиозного и языкового происхождения. Страна не располагала какими- либо существенными природными ресурсами и не имела даже прямого выхода к морским торговым путям. Конфедерацию сотрясали частые религиозные войны и борьба за власть. Но в начале XXI в. Швейцария уже была отнесена Всемирным банком к группе самых богатых государств мира (ее ВВП на душу населения составил 36.2 тыс. долл.) . В специально подготовленном исследовании Швейцарского восточного института такая метаморфоза объясняется в основном внедрением высокоэффективной общественно-политической системы управления. Она основана на соблюдении демократических правил политического противоборства, уважении прав человека и защиты национальных меньшинств. Однако в эти же годы особое значение приобрела проблема отношений Швейцарии и Европейского Союза. Начался сложный процесс обсуждения условий присоединения этой страны к европейской интеграции, который продолжается уже не одно десятилетие. Но как отмечал известный швейцарский общественный деятель Ш. Куке: «Современная Швейцария — достаточно богатая страна и может позволить себе длительное время придерживаться принципов „выборочной интеграции“, которая позволяет минимизировать давление Евросоюза и обеспечивает сохранение своей специфики, то есть прибыльности определенных секторов национальной экономики» В Швейцарии царит совершенно особый подход к самой сути ЕС. Швейцарские аналитики считают, что жесткая федеративная структура по образцу США не может быть моделью для дальнейшего развития политической системы ЕС. Вместо «европейского федерализма» в Швейцарии часто употребляется понятие «европейского космополитического образования». В Швейцарии исходят из того, что строительство ЕС является бесконечным процессом, у которого нет и не может быть «окончательной цели». Ни сам Евросоюз, ни отдельные входящие в него государства не должны образовывать «монопольного центра власти». Им отводится роль узлов сложно структурированной общественно-политической системы безопасности. На рубеже 20 — 21 столетий в Швейцарии возросло понимание того, что продолжительная стагнация, характерная для страны на рубеже веков, а также причины отставания от других государств Западной Европы кроются, в известной мере, и в приверженности Конфедерации так называемому «особому пути», предполагающему существование рядом с ЕС, но без непосредственного участия в нем при частичном вовлечении в процесс европейской интеграции. Это понимание подталкивало руководство Конфедерации к интенсификации диалога с Евросоюзом. Такой диалог особенно важен для Швейцарии с учетом того, что основным фактором роста ее экономики остается внешний спрос на швейцарскую продукцию (экспортная квота составляет 45 %), а львиная доля торговли приходится на страны Евросоюза (60 % экспорта и 82 % импорта). Первые соглашения между Швейцарией и Европейским союзом были подписаны еще в 1972 г. в рамках договора о вхождении в Европейское экономическое пространство ряда стран, находившихся в составе ЕАСТ. Таким образом, была создана основа для реализации четырех основных принципов: свободы движения товаров, капиталов, услуг и рабочей силы. Затем последовала целая серия референдумов, определивших характер дальнейших отношений с ЕС. В декабре 1992 г. был проведен всенародный плебисцит относительно целесообразности начала переговоров об условиях вступления страны в Евросоюз. Против проголосовало 50,4 % населения, перевес составил лишь 23.3 тыс. голосов, но за этим незначительным перевесом стоит тот факт, что против включения страны в европейскую интеграцию высказались 16 из 26 кантонов. В результате неодобрения начала переговорного процесса страна оказалась в наименее благоприятных торгово-экономических условиях по сравнению с другими европейскими странами. В этих условиях правительство приняло решение об изменении переговорной стратегии. В мае 2000 г. был проведен референдум относительно целесообразности заключения двустороннего соглашения с Евросоюзом по семи конкретным торгово-экономическим проблемам. Большинство населения (67.2 %) одобрило этот шаг. Против выступили только два кантона (в Тичино опасались возможного усиления притока иммигрантов из Италии, а в Швице вообще всегда против любого расширения связей с соседними странами). По мнению швейцарского правительства, подписанные соглашения обеспечивают стране почти три четверти всех преимуществ, которыми располагают государства — члены ЕС, но не вынуждают к соответствующим уступкам. При этом не наносится какой-либо ущерб государственному суверенитету. Все четыре политические партии, входящие в правительство (Федеральный совет), а также основные финансово-промышленные и профсоюзные объединения поддержали соглашения. 19 мая 2004 года были подписаны следующие соглашения: «Об освобождении от таможенного налогообложения экспорта в ЕС швейцарских переработанных сельхозпродуктов», «О вхождении Швейцарии в Европейское экологическое агентство», «О присоединении Швейцарии к системе европейского статистического учёта („Евростат“)», «О присоединении Швейцарии к Европейской программе развития в области масс-медиа», «О присоединении Швейцарии к европейской образовательной программе», «Об освобождении живущих в Швейцарии вышедших на пенсию чиновников ЕС о двойного налогообложения», «О присоединении Швейцарии к Шенгенскому и Дублинскому соглашениям», «О налогообложении процентов с размещённых в швейцарских банках европейских капиталов», «О присоединении Швейцарии к соглашению о борьбе с уклонением от непрямых налогов (НДС, акцизы и пр.)». .)». Конфедерации удалось всё-таки сохранить за собой право не оказывать правовую помощь странам-членам ЕС по делам, связанным с уклонением от прямых налогов, в рамках присоединения к Шенгену/Дублину. В 5 июня 2005 года на референдуме граждане Швейцарии высказались за вступление в Шенгенское пространство. С 12 декабря 2008 года Швейцария официально вступила в Шенгенское безвизовое пространство. На границах страны на всех наземных пропускных пунктах отменен паспортный контроль. В аэропортах Швейцарии паспортный контроль сохранился только до 29 марта 2009 года. За это время страна подготовила свои авиационные терминалы для обслуживания внутришенгенских авиарейсов, где паспортный контроль не требуется, и отделила эти рейсы от остальных международных терминалов. Что касается вопроса о распространении свободы перемещения на 10 новых государств-членов ЕС, то было принято решение вынести его на референдум, который состоялся 25 сентября 2005 года. Принцип свободы передвижения с новыми членами ЕС поддержали 55,95 % швейцарцев, сообщило Швейцарское телеграфное агентство. 8 февраля 2009 года граждане Швейцарии одобрили на референдуме продление соглашения с Евросоюзом о свободном движении рабочей силы, дав зеленый свет и на то, чтобы это право распространилось на граждан Румынии и Болгарии. В преддверии голосования ультраправые, выступавшие против, пугали сограждан тем, что приток в страну румын и болгар чреват ростом безработицы и преступности. Однако потеря привилегий в торговле с ЕС и ухудшение отношений, которыми грозил Брюссель, показались швейцарцам страшнее. Проведение референдума по вопросу о том, стоит ли гражданам Швейцарии по-прежнему принимать рабочих из стран Евросоюза и, в свою очередь, иметь право на работу в ЕС, понадобилось в связи со скорым истечением соглашения Берна и Брюсселя о свободном движении рабочей силы, а также вступлением в 2007 году Болгарии и Румынии в состав ЕС. Если к гражданам 25 стран ЕС швейцарцы уже более или менее привыкли, то к перспективе наплыва в страну румын и болгар многие отнеслись неоднозначно. В преддверии воскресного референдума на этих настроениях попыталась сыграть ультраправая Народная партия, из-за отказа которой расширить действие договора на Софию и Бухарест путем голосования в парламенте этот вопрос собственно и пришлось выносить на общенациональный плебисцит. Готовясь к нему, партия, давно известная своей жесткой антииммиграционной платформой, распространила по всей стране постеры, изображающие трех черных воронов, клюющих маленькую Швейцарию. Агитируя голосовать против, ультраправые пугали граждан тем, что приток дешевой рабочей силы из Румынии и Болгарии (по их определению — «стран третьей Европы») оставит без рабочих мест коренных швейцарцев, а также приведет к увеличению налогов и росту преступлений. Сторонники продления соглашений с ЕС, в свою очередь, обращали внимание на то, что негативный исход голосования поставит под угрозу весь комплекс отношений Швейцарии с Евросоюзом. Тем более что Брюссель не раз давал понять, что дискриминация двух новых членов ЕС недопустима и что швейцарское «нет» автоматически сведет на нет шесть других соглашений, касающихся взаимного снятия торговых барьеров. Некоторые еврочиновники даже говорили, что в качестве ответной меры на швейцарское «нет» ЕС может приостановить действие Шенгенского соглашения с этой страной. Ввиду того что около трети рабочих мест в Швейцарии напрямую связаны с ЕС, объем торговли с которым достигает €150 млрд ежегодно, отмена режима свободного трудоустройства создала бы огромные сложности и увеличила бы издержки швейцарских экспортеров. Однако если впервые решение впустить в страну рабочих из ЕС принималось на фоне экономического бума и потому в 2000 году его поддержали 67 % граждан, то сейчас Швейцария, как и большинство стран мира, переживает финансовый кризис. И хотя уровень безработицы в стране составляет всего 3 %, число безработных по сравнению с докризисными временами все же выросло. Поэтому всего за пару дней до референдума число сторонников продления соглашения с ЕС и двумя его новыми членами составляло только 50 %. Против выступали 43 %, тогда как оставшиеся по-прежнему не могли определиться. Тем не менее, около 60 % избирателей все-таки ответили на вопросы референдума утвердительно. И тем самым продемонстрировали, что угроза испортить отношения с Евросоюзом для них страшнее, чем возможный наплыв иммигрантов из Болгарии и Румынии. Одним из проблемных аспектов отношений Швейцарии с Евросоюзом является вопрос тайны банковских вкладов швейцарских банков. В современном мире вряд ли найдется какая-либо другая страна, кроме Швейцарии, в которой банки оказывали бы столь существенное воздействие не только на экономические, но и на общественно-политические процессы. Эта страна стала символом элитарной банковской системы и заслуженно пользуется репутацией самого надежного финансового сейфа в мире. Помимо высокой надежности многих привлекает гарантированная швейцарским законом тайна банковских счетов и имен их владельцев. Правда, в самой Швейцарии считают, что многое, связанное с этой проблемой, можно характеризовать как «популярный миф». В действительности в банковской системе страны не существует анонимных счетов (blind eyer), их владельцы хорошо известны руководству банков. Действует также строжайшая система постоянной проверки владельцев номерных счетов. И все же в последнее время давление мирового сообщества и, особенно, Евросоюза на Швейцарию возрастает. Несмотря на мощное давление Евросоюза, окончательно отказываться от принципа банковской тайны Швейцария не намерена. Данный принцип, по мнению главы Швейцарского национального банка X. Майера, является легитимным методом функционирования любого финансового объединения. Швейцария намерена в дальнейшем тщательно анализировать все возможные последствия реализации двусторонних соглашений с ЕС и его членами. В первую тройку актуальных проблем, по которым альпийская республика не готова идти на какие-либо радикальные уступки, входят вопросы сохранения банковской тайны, независимости швейцарского франка и незыблемости принципа нейтралитета во внешней политике. В целом, Швейцария не готова вести дела в банковской сфере по «правилам Евросоюза». Считается, что страна была вынуждена уже пойти на значительные уступки, что существенно девальвирует привлекательность ее национальных банков. Такое развитие событий особенно не устраивает небольшие приватные (семейные) банки, составляющие основу финансовой системы страны. В новое столетие Швейцария вступает в состояние активного поиска иного имиджа и места в современном мире. Оказавшись в географическом центре расширяющегося Евросоюза, Швейцария вынуждена вырабатывать новые принципы международного сотрудничества. Европа остается для Швейцарии важнейшим партнером экономическим, политическим, культурным. В целом, это направление внешней политики Швейцарии в новом веке стало более прагматичным. Швейцария не является членом Евросоюза и, очевидно, долго еще им не станет. При этом у нее есть ряд неоспоримых преимуществ перед ЕС, как-то: дипломатическая компетенция Швейцарии, ее надежность и репутация, завоеванная в сфере защиты прав человека. И Швейцария достаточно успешно научилась их использовать в новых реалиях.

Отношения Швейцарской Конфедерации и России

Отношения между Швейцарией и Россией отличаются стабильностью и демонстрируют с начала века устойчивую тенденцию к расширению. Новый этап в этих отношениях начался с официального визита в Россию президента Швейцарии Флавио Коти в декабре 1998 года. Именно тогда были заложены основы политического сотрудничества обеих стран в сфере борьбы с международной преступностью, отмыванием «грязных» денег, торговлей наркотиками и нелегальной иммиграцией. Однако экономический кризис 1998 года в России не позволил тогда реализовать все имеющиеся для увеличения инвестиций Швейцарии в российскую экономику. В последующие годы эти намерения неоднократно подтверждались на самом высоком уровне, а министр иностранных дел Швейцарии Йозеф Дайс еще раз заверил в 1999 году российское руководство, что его страна готова к дальнейшему углублению взаимных отношений и ждет от России соответствующего отклика на свои предложения. Пока руководство РФ раздумывало над перспективами российско-швейцарских отношений, произошла страшная катастрофа, последствия которой ощущались долгие годы. 1 июля 2002 г. над Боденским озером по вине швейцарской авиадиспетчерской компании «Скайгайд» был сбит пассажирский самолет «Башкирских авиалиний», на борту которого находилось большое количество детей. «Эта трагедия, — заявил президент Швейцарии Паскаль Кушпен во время визита в Москву в июле 2003 г., — тяжелой тучей нависла над нами, омрачая отношения между Россией и Швейцарией». Президенты обеих стран подтвердили приверженность принципам многополярного мира, осудили все проявления международного терроризма и с удовлетворением констатировали заметные успехи в совместной борьбе с отмыванием денег. В первые годы нового столетия Швейцария вышла на 4-е место как по объему инвестиций в российскую экономику (1,3 млрд долларов), так и по количеству работающих на территории России предприятий (более 450). Деловые круги Швейцарии действительно проявляют огромный интерес к необъятному потребительскому рынку РФ. Однако несовершенство законодательной базы и отсутствие привычных для швейцарцев гарантий и условий предпринимательства тормозят этот процесс. В 2004 году был проведен международный семинар, посвященный России, организатором которого выступило швейцарское неправительственное объединение «Совет по сотрудничеству Швейцария-Россия». Спецпредставитель президента РФ по международному энергетическому сотрудничеству Игорь Юсуфов, принявший участие в этом семинаре, заявил, что «Швейцария, обладающая большими финансовыми ресурсами, может мобилизовать новейшие технологии для использования их в российском энергетическом секторе, потенциал вложений в который достигает $200 миллиардов… Такой семинар, этот формат, рамка этого формата очень важна для того, чтобы имидж России здесь позитивно продвигать и привлекать инвесторов». Участники семинара обсудили современный образ России в Швейцарии, согласившись при этом, что швейцарские средства массовой информации пытаются отойти от стереотипов и представить более или менее объективный образ России. «Этот форум происходит в очень важное время, когда вся Европа с тревогой смотрит на Россию, и стереотипы старых времен опять выходят наружу», — отметил известный немецкий политолог Александр Рар. По словам Рара, по сравнению с другими странами Европы «именно швейцарцы относятся к России менее эмоционально и менее стереотипно». Представитель федерального департамента иностранных дел Швейцарии Жан-Жак Дедардель также подчеркнул, выступая на семинаре, что Конфедерация заинтересована в улучшении имиджа России для развития всестороннего сотрудничества между странами. «Отношение к России окрашено эмоциями, иногда отрицательными, иногда позитивными, но эти представления базируются на клише, стереотипах», — отметил он. Всего в семинаре приняли участие около 150 человек — предприниматели, политологи, представители различных партий и федеральных ведомств Швейцарии, журналисты. По приглашению организаторов в Берн также приехал председатель Конституционного суда России Валерий Зорькин. Таким образом, несмотря на упомянутые выше проблемы, сотрудничество Россия-Швейцария продвинулось еще на шаг вперед. На заседании Федерального совета по вопросам внешней политики в 2005 году отмечалось, что более тесными должны стать отношения Швейцарии с Россией, Китаем, Японией, Бразилией, Индией, балканскими странами, ЮАР. В 2007 году был сделан еще один значительный шаг к сближению Швейцарии и России, когда Государственный Секретариат Швейцарии по науке и технологиям включил Россию в список приоритетных стран для развития отношений. Как сообщил в Берне «Интерфаксу» представитель отдела двустороннего сотрудничества этого ведомства Маркус Гюблер, «Россия наравне с Индией, Китаем и ЮАР числится в списке стран, стратегическое сотрудничество с которыми на период 2008—2011 гг. планирует развивать Государственный секретариат Швейцарии по науке и технологиям». Он также добавил, что «за четыре года объем ресурсов, направляемых на финансирование программ двустороннего сотрудничества с упомянутыми странами, достигнет суммы в 53 млн швейцарских франков (почти 32 млн евро). Из них на российское направление будет выделено 8-10 млн швейцарских франков (4,82-6 млн евро)». М.Гюблер отметил, что «российско-швейцарское сотрудничество в научно-технологической сфере главным образом основано на индивидуальных контактах ученых и исследователей из двух стран и, в основном, затрагивает сферы естественных наук, экологии и нанотехнологий, а также социологии и экономики». В скором времени, добавил он, «ожидается открытие Швейцарского дома в России, который послужит платформой для дальнейшего развития отношений между представителями научного сообщества из двух стран… Двустороннее сотрудничество между Швейцарией и Россией основано на принципах взаимной выгоды, устойчивом развитии, рассчитанном на длительный срок, и на финансировании проектов в равных долях». После того, как Россия и Грузия разорвали дипломатические отношения в период конфликта вокруг Южной Осетии в августе 2008 года, возник естественный вопрос о том, какая страна сможет представлять интересы России в Грузии. 13 декабря 2008 года в Москве Сергей Лавров и его швейцарская коллега Мишлин Кальми-Ре подписали ноту о том, что интересы России в Грузии будет представлять именно Швейцария. Было объявлено об открытии в ближайшее время при посольстве Швейцарии в Тбилиси так называемой «секции интересов России». Сергей Лавров в связи с этим заявил: «Мы признательны нашим швейцарским коллегам за такую договоренность. Она, безусловно, будет отвечать интересам нормализации обстановки и, в конечном счете, интересам поддержания контактов между российским и грузинским народами». Очевидно, что такой шаг укрепил взаимодоверительные отношения Швейцарии и России. Следует также отметить, что швейцарские газеты нередко упоминают о необходимости поддержания хороших отношений с Россией. В частности, «Swissinfo» в статье, посвященной проведению первой полноформатной встречи глав внешнеполитических ведомств России и США Сергея Лаврова и Хиллари Клинтон по вопросам будущих основ российско-американских отношений, которая проводилась в Женеве, особо отмечает, что «Россия имеет дружественные отношения с Женевой. На протяжении многих лет генеральным директором ООН в Женеве является россиянин (в настоящее время — Сергей Орджоникидзе)…Женева также являлась местом проведения знаменитого саммита 1985 года между Р.Рейганом и М.Горбачевым, который ознаменовал начало конца СССР. Не следует также забывать, что именно здесь проходили переговоры с Грузией после ее военного столкновения с Россией в августе 2008 года». Таким образом, можно заключить, что отношения Швейцарской Конфедерации и России находятся в стадии их расцвета, и это касается как чисто политических вопросов, так и вопросов, связанных с экономическим сотрудничеством обеих стран. Безусловно, еще далеко не весь потенциал использован сторонами, однако наметившиеся тенденции к расширению отношений дает возможность предположить, что предстоит дальнейшая интенсификация диалога между сторонами, целью которого станет устранение оставшихся препятствий.

Отношения Швейцарии и США в начале 21 века

Еще в 2000 году на первом месте для Швейцарии находилась Европа. Но с течением времени руководство ФДИД (Федерального Департамента иностранных дел) осознало, что в новых условиях страна должна уделять повышенное внимание и остальному миру. По этой причине ФДИД в сотрудничестве с другими министерствами разработал соответствующие стратегии, в частности, в плане интенсификации отношений с США, занимающими вне Европы второе место в списке важнейших торговых партнеров Швейцарии. В этой связи следует отметить, что М.Кальми-Ре (которая начала руководить ФДИД в феврале 2003 года) позволяла себе высказывать критические замечания в адрес внешней политики США. Так, в октябре 2003 года, выступая в Нью-Йорке, она указала на недопустимость гегемонии одной супердержавы и необходимость соблюдения принятых на международной арене правил игры. Безусловно, даже в самой Швейцарии многие не склонны были одобрять такое поведение главы ФДИД. В результате, после двух с лишним лет пребывания на посту руководительницы швейцарского внешнеполитического ведомства, назрела необходимость корректур во внешнеполитическом курсе страны. Внешняя политика «проб и ошибок» резко порывала с принятыми в Швейцарии дипломатическими традициями, на первом плане которых стоят доверительность и предсказуемость. М.Кальми-Ре обвиняли также в «правочеловеческом» и «гуманитарном» уклонах во внешней политике, при этом за бортом ее внимания оставались такие важные досье, как отношения Швейцарии и США, тогда как элементарные соображения реальной политики должны были бы привести ее к необходимости поддерживать с США хорошие отношения. Однако признавалось, что со времени вступления на свой пост М.Кальми-Ре удалось значительно расширить палитру внешнеполитических тем. Поэтому состоявшееся 18 мая 2005 года специальное заседание Федерального совета, посвященное исключительно вопросам внешней политики Конфедерации, можно назвать давно назревшим. М.Кальми-Ре во многом согласилась с прозвучавшей в ее адрес критикой. По итогам заседания было объявлено, что речь должна идти не о кардинальной перемене внешнеполитического курса, а о смещении акцентов, которое подчеркивает в качестве цели необходимость защиты своих собственных (прежде всего экономических) интересов и указывает на универсальность швейцарской внешней политики. На отношения Швейцарии с США серьезно повлияли события в Ираке (военный кризис в марте-мае 2003 года). Тогда Швейцария заняла позицию, в целом разделяемую подавляющим большинством мирового сообщества. Швейцария заявила устами П.Кушпена, что считает недопустимым наличие у Ирака оружия массового поражения и что иракцы намеренно размещают свои войска вблизи гражданских объектов, что противоречит международному праву, что США сами нарушили международное право, начав войну в Ираке, но и режим Хусейна неоднократно и в грубой форме нарушал права человека. Тем не менее, со стороны Швейцарии было недвусмысленно подчеркнуто, что она выступает за исчерпывание всех мирных средств для того, чтобы принудить Багдад к разоружению. Лишь после этого на рассмотрение может быть поставлен вопрос о применении силы как последнего средства. Следует отметить, что в начале века вразрез с предыдущей практикой государственные мужи стали давать добро на пролеты военных самолетов и транзит грузов Североатлантического альянса, направлявшихся в кризисные регионы (условием этого, правда, было наличие мандата ООН). После бурных внутриполитических дискуссий швейцарцы также присоединились к натовской программе «Партнерство ради мира». Однако накануне войны в Ираке Швейцария заняла достаточно жесткую позицию по вопросу пролетов самолетов антииракской коалиции над ее территорией, не обнаруживая безоговорочную поддержку действиям НАТО и их лидеру США. Во-первых, было заявлено, что в случае, если США начнут операцию против Ирака без санкции СБ ООН, Швейцария откажет Вашингтону в любых пролетах с военными целями, что и было в итоге сделано. Во-вторых, если резолюция Совет Безопасности ООН одобрит силовой вариант, Швейцария будет предоставлять США возможности пролета через свою территорию «от случая к случаю», то есть взвешивая все за и против каждый раз отдельно. Никакого генерального разрешения на пролеты предусмотрено не было. Параллельно Федеральный совет принял решение о запрете С.Хусейну на въезд в Швейцарию на основании «тяжелых нарушений прав человека и военных преступлений». Этот шаг служил целью сохранить реноме страны в качестве поборника прав человека. Одновременно Швейцария наотрез отказалась выслать из страны иракских дипломатов, как того требовал от нее Вашингтон. Федеральный совет принял прагматичную позицию и не остановил военно-техническое сотрудничество с США, при этом П.Кушпен подчеркнул, что «Швейцария будет занимать нейтральную позицию, в частности, она прекратит поставки вооружений, которые могут быть непосредственно применены в зоне военных действий». Оценивая результаты войны, в Берне посчитали, что успешно опробованная американцами в Ираке доктрина превентивной войны привела к определенной милитаризации мировой дипломатии. Отказавшись от многосторонней дипломатии, Вашингтон перешел к тактике создания коалиций при помощи экономических посулов и политических угроз, что означает во многом возвращение к военно-политическому мышлению 19 века. Война в Ираке решила одну проблему, но создала массу новых, после нее мир не стал стабильнее. Следует отметить, что Швейцария до настоящего времени представляет интересы США на Кубе и в Иране. Что касается банковской сферы, то и тут существовали и существуют серьезные противоречия швейцарской и вашингтонской позиций. В то время как Европа проявляет свойственную ей деликатность в отношении «швейцарских гномов», США настойчиво добиваются своих целей и вынуждают Швейцарию идти на некоторые уступки. Так, с января 2001 года вступило в силу соглашение между обеими странами, в соответствии с которым со счетов американских граждан в пользу государственной казны США автоматически снимается 31 % от накопленного в течение года дохода по вкладам. В этой связи следует упомянуть, что 10 декабря 2007 года швейцарский банк UBS, крупнейший в Европе по размеру активов, объявил о списании десяти миллиардов долларов, причиной которого стал именно ипотечный кризис в США. А в октябре 2008 года правительство Швейцарии приняло решение о выкупе 10 % акций банка за 3,9 млрд евро в связи с мировым финансовым кризисом. Это был сильный удар по Швейцарии, маленькой альпийской стране, известной как родина privat banking, частного банковского дела. Швейцарская система privat banking всегда занимала лидирующее положение в мировой банковской сфере, что вызывает зависть. Не удивительно, что во время экономического кризиса Швейцария превратилась в удобный громоотвод для финансово озабоченных стран, которые могут таким образом разрядить свою неудовлетворенность и отвлечь внимание своих граждан от изъянов в собственных плохо действующих налоговых системах. К тому же Швейцария преследует на достижение амбициозной цели — войти к 2015 году в первую тройку мировых финансовых центров наряду с Нью-Йорком и Лондоном. На фоне такой обстановки обращение в августе 2008 года Министерства юстиции США в суд с требованием к швейцарскому банку UBS удовлетворить запросы американских налоговиков (Internal Revenue Service) и раскрыть имена клиентов UBS из Америки, открывших в банке анонимные счета, оказалось весьма некстати. Властям Швейцарии пришлось сотрудничать с американской стороной и пойти на значительные уступки.

Миграционная политика Швейцарии в XX — начале XXI вв