|

«The Grand Old Lady» |

|

Goodison Park in August 2022 |

|

|

|

| Former names | Mere Green Field |

|---|---|

| Location | Goodison Road Walton, Liverpool, England |

| Coordinates | 53°26′20″N 2°57′59″W / 53.43889°N 2.96639°WCoordinates: 53°26′20″N 2°57′59″W / 53.43889°N 2.96639°W |

| Public transit | Kirkdale railway station |

| Owner | Everton F.C. |

| Operator | Everton F.C. |

| Capacity | 39,414[1] |

| Record attendance | 78,299 (Everton vs Liverpool, 18 September 1948) |

| Field size | 100.48 by 68 metres (109.9 yd × 74.4 yd)[1] |

| Surface | Desso GrassMaster |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 24 August 1892; 130 years ago |

| Renovated | Expected end of 2028 |

| Demolished | Expected start of 2024 |

| Construction cost | £3,000[nb 1] |

| Architect | Kelly Brothers Henry Hartley Archibald Leitch |

| Tenants | |

| Everton F.C. (1892–2024) |

Goodison Park is a football stadium in the Walton area of Liverpool, England, 2 miles (3 km) north of the city centre. It has been the home of Premier League club Everton F.C. since 1892 and has an all-seated capacity of 39,414.[1]

Goodison Park has hosted more top-flight games than any other stadium in England.[2] It has also been the venue for an FA Cup Final and numerous international fixtures, including a semi-final match in the 1966 World Cup.

History[edit]

Before Goodison Park[edit]

Everton originally played on an open pitch in the south-east corner of the newly laid out Stanley Park (on a site where rivals Liverpool FC considered building a stadium over a century later). The first official match after being renamed Everton from St. Domingo’s was at Stanley Park, staged on 20 December 1879 with St. Peter’s being the opposition, and admission was free. In 1882, a man named J. Cruit donated land at Priory Road with the necessary facilities required for professional clubs, but asked the club to leave his land after two years because the crowds became too large and noisy.[3]

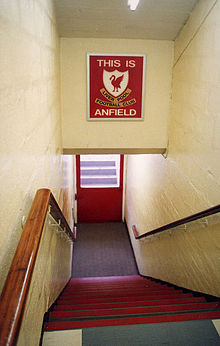

Everton moved to nearby Anfield Road, a site where proper covered stands were built. Everton played at the Anfield ground from 1884 until 1892.[4] During this time the club turned professional entering teams in the FA Cup.[5] They became founding members of the Football League winning their first championship at the ground in 1890–91.[6] Anfield’s capacity grew to over 20,000 with the club hosted an international match with England hosting Ireland. During their time at Anfield, Everton became the first club to introduce goalnets to professional football.[7]

In the 1890s, a dispute about how the club was to be owned and run emerged with John Houlding, Anfield’s majority owner and Everton’s Chairman, at the forefront.[3] Houlding disagreed with the club’s committee initially disagreeing about the full purchase of the land at Anfield from minor land owner Mr Orrell escalating into a principled disagreement of how the club was run. Two such disagreements included Houlding wanting Everton to sell only his brewery products during an event and for the Everton players to use his public house The Sandon as changing room facilities.[8]

The most famous of the disagreements concerns the level of increased rent Everton were asked to pay. In 1889, Everton paid £100 to Houlding in rent which by the 1889–90 season had risen to £250.[8] Everton had to pay for all works and stands. The dispute escalated to a rent of £370 per year being demanded. In the complicated lead up to the split in the club, the rent dispute is too simplistic to be singled out as the prime cause. The dispute was compounded by many minor disputed points.[citation needed]

The flashpoint was a covenant in the contract of land purchase by Houlding from Orrell causing further and deep friction. A strip of land at the Anfield ground bordering the adjacent land owned by Mr Orrell, could be used to provide a right of way access road for Orrell’s landlocked vacant site. In early 1891 the club erected a stand on this now proposed roadway, which was also overlapping Orrell’s land, unbeknown to the Everton F.C. Committee. In August 1891 Orrell announced intentions of developing his land next to the football ground, building an access road on the land owned by Houlding and occupied by Everton F.C.[citation needed]

Everton F.C. stated they knew nothing of the covenant, Houlding stated they did. This situation created great distrust leading to friction between Houlding and the Everton F.C. Committee. The rift and distrust between the two parties was on three levels, Houlding’s personal business intentions, politically and morally. Nevertheless, the club faced a dilemma of having to destroy the new revenue generating stand or compensate Orrell.[citation needed]

Houlding’s way around the problem was to propose a limited company with floatation of the club enabling the club to purchase Houlding’s and Orrell’s land outright, hoping to raise £12,000. Previous attempts to raise money from the community had failed miserably. This would have meant the club would need to find £6,000 in cash with an additional £4,875 mortgage. The Everton Committee initially accepted Houlding’s proposal in principle, yet voted against it at a meeting.[9]

After much negotiating and brinkmanship on both sides Everton vacated Anfield, leaving Houlding with an empty stadium with no one to play in it. As a consequence, Houlding formed his own football club, Liverpool, to take up residence at the stadium.[8]

The clubs themselves have differing versions of events of why it occurred.

Houlding explained why this situation arose in a Liverpool match programme against Cliftonville in April 1893. He pointed out that he had given Everton a rent free loan until the club started to make money. If the club had gone bust he would have lost it all.

Despite making no profit in this respect, the issue that upset the members at Everton most was his plan to sell Anfield and the land adjoining, with Houlding himself profiting. He felt it was a reasonable reward for the risk he had ventured in the club for nine years. Houlding, as the ambitious businessman he was, saw a great future for the club. He wanted the club to have its own home ground and wanted them to buy land so the club could expand in due course.

Unfortunately most of the Everton FC board members failed to share his forward thinking and lacked confidence. They wanted instead a long term rent deal on all the land, but for this to be acceptable to Houlding, he wanted a rent at a price considered too high for the Club. The members reacted to that by «offering» Houlding less rent. Houlding unsurprisingly refused to accept this stating that he did not want to be dictated: «I cannot understand why a gentleman that has done so much for the club (Everton) and its members should be given such treatment».

— Liverpool FC version of events[8]

During their spell at Anfield, John Houlding decided to charge the Club rent based on the increase of gate receipts from attendances and not, as was previously the case, at a fixed rate.

«This – along with other conflicts with Everton – led to the Club being expelled from Anfield in 1892 and in need of a new home….

fully expecting Houlding to dismiss Everton from their Anfield home, he (George Mahon) acquired land on a patch off Stanley Park called ‘Mere Green Field’ and also made sure that the Club kept their name.»

— Everton FC version of events[10]

Genesis of Goodison Park[edit]

On 15 September 1891, a general meeting took place at Royal Street Hall, near Everton Valley.[11] Everton’s chairman John Houlding proposed that a limited company be formed with the new company purchasing his land and local brewer Joseph Orrell’s adjacent land for a combined £9,237.[11] A club run as a limited company was unusual for the time as football clubs were usually run as «sports clubs» with members paying an annual fee. The proposal was supported by William Barclay, the club secretary and a close friend of Houlding.[12]

Liberal Party politician and Everton board member George Mahon fought the proposal putting forward his own amendment which was carried by the Everton board. At the time Everton’s board contained both Conservative and Liberal Party councillors. Houlding and Mahon had previously clashed during local elections.[13][14]

Both men agreed that Everton should operate as a limited company; however, they had different ideas about share ownership. Houlding suggested that 12,000 shares be created with each Everton board member given one share and the other shares sold to the public or Everton board members. Mahon disagreed and proposed that 500 shares be created with no member carrying more than 10 shares with board members given «7 or 8» shares. Mahon reasoned «we would rather have a large number of individual applications so that there will be more supporters of the club.»[12]

A special general meeting was convened at the former Liverpool College building on Shaw Street on 25 January 1892. John Houlding’s proposal was defeated once more with George Mahon suggesting that Everton relocate to another site. A heckler shouted, «You can’t find one!» Mahon responded «I have one in my pocket» revealing an option to lease Mere Green field, in Walton, Lancashire, the site of the current Goodison Park.[11]

The Liverpool press were partisan. The proposal was deemed to be a positive move for the club by the Liberal-leaning Liverpool Daily Post which described Houlding’s ousting as «having shaken off the incubus.»[15] The Tory-supporting Liverpool Courier and Liverpool Evening Express—owned by Conservative MP for Everton, John A. Willox, a Trustee of the Licensed Victuallers’ and Brewers’ Association—took Houlding’s side. The Courier published letters regularly criticising Mahon’s supporters—many of which were anonymous.[16] Philanthropist William Hartley, a jam manufacturer and Robert William Hudson, a prominent soap-manufacturer supported Mahon.[17]

The stadium was named Goodison Park because the length of the site was built against Goodison Road. The road was named after a civil engineer named George Goodison who provided a sewage report to the Walton Local Board in the mid-1800s later becoming a local landowner.[12]

Behold Goodison Park! no single picture could take in the entire scene the ground presents, it is so magnificently large, for it rivals the greater American baseball pitches. On three sides of the field of play there are tall covered stands, and on the fourth side the ground has been so well banked up with thousands of loads of cinders that a complete view of the game can be had from any portion.

The spectators are divided from the playing piece by a neat, low hoarding, and the touch line is far enough from it to prevent those accidents which were predicted at Anfield Road, but never happened… Taking it all together, it appears to be one of the finest and most complete grounds in the kingdom, and it is hoped that the public will liberally support the promoters.

«Out of Doors», October 1892[18]

The Mere Green field was owned by Christopher Leyland with Everton renting until they were in a position to buy the site outright. Initially, the field needed work as parts of the site needed excavation, the field was levelled, a drainage system was installed and turf was laid. This work was considered to be a ‘formidable initial expenditure’ with local contractor Mr Barton contracted to work on the 29,471 square yards (25,000 m2) site at 4½d per square yard—a total cost of £552. A J. Prescott was brought in as an architectural advisor and surveyor.[11]

Walton-based building firm Kelly Brothers were instructed to erect two uncovered stands that could each accommodate 4,000 spectators. A third covered stand accommodating 3,000 spectators was also requested. The combined cost of these stands was £1,640. Everton inserted a penalty clause into the contract in case the work was not completed by its 31 July deadline.[11] Everton officials were impressed with the builder’s workmanship agreeing two further contracts: exterior hoardings were constructed at a cost of £150 with 12 turnstiles installed at a cost of £7 each.[11] In 1894, Benjamin Kelly of Kelly Brothers was appointed as a director of Everton.[19]

Dr. James Baxter of the Everton committee donated a £1,000 interest-free loan to build Goodison Park. The stadium was England’s first purpose-built football ground, with stands on three sides. Goodison Park was officially opened on 24 August 1892 by Lord Kinnaird and Frederick Wall of the Football Association. No football was played; instead the 12,000 crowd watched a short athletics event followed by music and a fireworks display.[11] Upon its completion the stadium was the first joint purpose-built football stadium in the world; Celtic’s basic Celtic Park ground in Glasgow, Scotland was inaugurated on the same day as Goodison Park.[20]

The first known image of Goodison Park. Published by the Liverpool Echo in August 1892

The first football match at Goodison Park was on 2 September 1892 between Everton and Bolton Wanderers. Everton wore its new club colours of salmon and dark blue stripes and won the exhibition game 4–2.[20] The first league game at Goodison Park took place on 3 September 1892 against Nottingham Forest; the game ended in a 2–2 draw. The stadium’s first competitive goal was scored by Forest’s Horace Pike and the first Everton goal scored by Fred Geary. Everton’s first league victory at their new ground came in the next home game with a 6–0 defeat of Newton Heath in front of an estimated 10,000 spectators.[21]

It was announced at a general meeting on 22 March 1895 that the club could finally afford to buy Goodison Park. Mahon revealed that Everton were buying Goodison Park for £650 less than the price of Anfield three years earlier, with Goodison Park having more land and a 25% larger capacity. The motion to purchase Goodison Park was passed unanimously.[12] Dr. Baxter also lent the club £5,000 to redeem the mortgage early at a rate of 3½%.[22] By this time the redrawing of political boundaries put Walton, and hence Goodison Park, inside the City of Liverpool.[23]

In 1999, The Independent newspaper journalist David Conn unexpectedly coined the nickname «The Grand Old Lady» for the stadium when he wrote «Another potential suitor has apparently thought better of Everton, walking away on Tuesday from the sagging Grand Old Lady of English football, leaving her still in desperate need of a makeover.»[24]

Structural developments[edit]

The Goodison Park structure was built in stages. In the summer of 1895 a new Bullens Road stand was built and a roof placed on the original Goodison Road stand but only after five directors, including chairman, George Mahon had resigned over what was described in the club minutes as ‘acute administrative difficulties’.[25] In 1906, the double-decker Goodison Avenue Stand was built behind the goal at the south end of the ground. The stand was designed by Liverpool architect Henry Hartley[20] who went on to chair the Liverpool Architectural Society a year later.[26] The club minutes from the time show that Hartley was unhappy with certain aspects of the stand and the poor sightlines meant that the goal line had to be moved seven metres north, towards Gwladys Street. In January 1908, he complained that his fees had not been paid and the bill for the stand was near £13,000.[11] There were 2,657 seats on its upper tier with a terrace below.

Archibald Leitch designed the Goodison Road Stand with construction in 1909. In September that year Ernest Edwards, the Liverpool Echo journalist who christened the terrace at Anfield the «Spion Kop», wrote of the newly built stand, «The building as one looks at it, suggests the side of Mauretania at once.»[27] The stand was occasionally referred to as the «Mauretania Stand», in reference to the Liverpool-registered RMS Mauretania, then the world’s largest ship, which operated from the Port of Liverpool.[28]

The two-tier steel frame and wooden floor Bullens Road Stand, designed by Archibald Leitch, was completed in 1926. The upper tier was seated, with terracing below, a part of the ground called The Paddock. Few changes were made until 1963 when the rear of the Paddock was seated and an overhanging roof was added. The stand is known for Archibald Leitch’s highly distinctive balcony trusses which also act as handrails for the front row of seats in the Upper Bullens stand. Goodison Park is the only stadium with two complete trusses designed by Leitch. Of the 17 created, only Goodison Park, Ibrox and Fratton Park retain these trusses.[3]

Everton constructed covered dugouts in 1931. The idea was inspired by a visit to Pittodrie to play a friendly against Aberdeen, where such dugouts had been constructed at the behest of the Dons’ trainer Donald Colman. The Goodison Park dugouts were the first in England.[29]

Goodison Park was bombed in September 1940

The ground become an entirely two-tiered affair in 1938 with another Archibald Leitch stand at the Gwladys Street end. The stand completed at a cost of £50,000, being delayed because an old man would not move from his to be demolished home.[29] The original Gwladys Street having had terraced houses on either side, with those backing on to the ground making way for the expansion. Architect Leitch and Everton Chairman Will Cuff became close friends with Cuff appointed as Leitch’s accountant with Leitch moving to nearby Formby.[3]

In 1940, during the Second World War, the Gwladys Street Stand suffered bomb damage. The bomb had landed directly in Gwladys Street and caused serious injury to nearby residents. The bomb splinter damage to the bricks on the stand is still noticeable. The cost of repair was £5,000 and was paid for by the War Damage Commission.[29]

The Director’s minutes read: «It was decided also that Messrs A. Leitch be instructed to value the cost of complete renewal of damaged properties and that a claim should be forwarded to the War Damage Claims department within the prescribed 30 days.

«The damage referred to included the demolition of a wide section of the new stand outer wall in Gwladys St, destruction of all glass in this stand, damage to every door, canteen, water and electricity pipe and all lead fittings: perforate roof in hundreds of places.

«On Bullens Road side, a bomb dropped in the school yard had badly damaged the exterior wall of this stand and the roof was badly perforated here also. A third bomb outside the practice ground had demolished the surrounding hoarding and had badly damaged glass in the Goodison Ave and Walton Lane property.»[30]

The first floodlit match at Goodison Park took place when Everton hosted Liverpool on 9 October 1957 in front of 58,771 spectators.[21] Four pylons 185 feet (56 m) each with 36 lamps installed were installed behind each corner of the pitch. At the time, they were tallest in the country. There was capacity for 18 more lamps per pylon if it was felt the brightness was insufficient for the game. Each bulb was a 1,500 watt tungsten bulb 15 inches in diameter and cost 25 shillings. It was recommended that the club made a habit of changing them after three to four seasons to save the club performing intermittent repairs. MANWEB installed a transformer sub-station to cope with the 6,000 volt-load.[21]

The first undersoil heating system in English football was installed at Goodison Park in 1958,[31] with 20 miles (30 km) of electric wire laid beneath the playing surface at a cost of £16,000. The system was more effective than anticipated and the drainage system could not cope with the quantity of water produced from the melting of frost and snow. As a consequence the pitch had to be relaid in 1960 to allow a more suitable drainage system to be installed.[11]

The Everton chairman Sir John Moores who presided over the club between 1960 and 1973 provided finances for the club in the form of loans to become involved in large-scale redevelopment projects and compete with other clubs for the best players, for a period of time under his stewardship Everton were known as ‘The Mersey Millionaires’.[32]

Goodison Park featured in the filming of The Golden Vision, a BBC film made for television. The matches featured in the film were Division One games against Manchester City on 4 November 1967 (1–1 draw) and 18 November 1967 versus Sheffield United (1–0 win)[33]—the scorer of the winner that day was Alex Young,[34] also known as The Golden Vision or Golden Ghost after whom the film was named.[33]

Everton were the first club to have a scoreboard installed in England.[35] On 20 November 1971 Everton beat Southampton 8–0 with Joe Royle scoring four, David Johnson three and Alan Ball one. The scoreboard did not have enough room to display the goal scorer’s names and simply read «7 9 7 9 8 9 9 7» as it displayed the goal scorers’ shirt numbers instead.[36]

The Goodison Road Stand was partially demolished and rebuilt during the 1969–70 season with striking images of both old and new stands side by side. The new stand opened 1971, at a cost of £1 million. The new stand housed the 500 and 300 members clubs[11] and an escalator to the tallest stand in the ground—the Top Balcony.[3] However, not everyone thought that the upgrade was necessary at the time. Journalist Geoffrey Green of The Times wrote «Goodison Park has always been a handsome fashionable stage for football, a living thing full of atmospherics-like a theatre. And now it has stepped into the demanding seventies with a facelift it scarcely seemed to need compared with some of us I know. New giant stands in place of the old; the latest in dazzling floodlight systems that cast not a shadow. A cathedral of a place indeed, fit for the gods of the game.»[37]

The Safety of Sports Grounds Act 1975 saw the Bullens Road Stand extensively fireproofed with widened aisles, which entailed closure of parts of the stand.[11] Because of the closure, Anfield was chosen over first choice Goodison Park for a Wales vs. Scotland World Cup qualifying tie.[38]

Following Moores’ exit from Everton’s hierarchy, minimum changes had been made to Goodison Park’s structure due to costs,[39] two British Government Acts; the Safety of Sports Grounds Act 1975 and Football Spectators Act 1989 had forced the club’s hand into improving the facilities. Upon Moore’s death the club was sold to Peter Johnson.[40]

Everton legends William Ralph ‘Dixie’ Dean[41] and former manager Harry Catterick[42] both died at Goodison Park. Dean suffered from a heart attack aged 73 in 1980, whilst Catterick died five years later, also suffering a heart attack aged 65.

Everton F.C. celebrated the centenary of Goodison Park with a game against German club side Borussia Mönchengladbach in August 1992.[43] In addition, 200 limited edition medals were created[44] and Liverpool based author and journalist Ken Rogers wrote a book One Hundred Years of Goodison Glory to commemorate the occasion.

Post-Taylor Report[edit]

Following the publication of the 1990 Taylor Report, in the wake of the Hillsborough disaster, top-flight English football grounds had to become all-seated.[45] At the time three of the four sides of the ground had standing areas. The Enclosure, fronting the main stand, had already been made all-seated in time for the 1987–88 season and was given the new name of Family Enclosure. The Paddock, the Park End terrace and the Gwladys Street terrace, known as ‘the Ground’, were standing and had to be replaced.

The fences around the perimeter of the ground fronting the terracing (which were to prevent fans, notably hooligans, running onto the pitch) were removed immediately post Hillsborough, in time for the rearranged league fixture with Liverpool. The Everton match versus Luton Town in May 1991 was the final time that Gwladys Street allowed standing spectators.[21] Seats were installed in the Paddock, while the Lower Gwladys Street was later completely rebuilt to accommodate seating with new concrete steps.

Everton opted to demolish the entire Park End stand in 1994 and replace it with a single-tier cantilever stand, with the assistance of a grant of £1.3 million from the Football Trust.[29]

Current structure[edit]

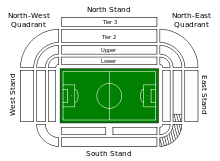

Goodison Park has a total capacity of 39,572 all-seated and comprises four separate stands: the Goodison Road Stand, Gwladys Street Stand, Bullens Road Stand, and the Park End Stand.[46]

Goodison Road Stand[edit]

Built in sections from 1969 to 1971, replacing the large double-decker 1909 Archibald Leitch designed stand. The Goodison Road Stand is a double-decker stand with the lower deck being two-tier. Each level is given a separate name. The middle-deck level is known as the Main Stand and is fronted by another seated section known as the Family Enclosure. The Enclosure was originally terracing prior to the advent of all-seater stadia. The Top Balcony is the highest part of the stadium. The stand became all seated in 1987 and now has a capacity of 12,664.[citation needed]

The back wall of the stand cuts into the stand because of the non-square nature of the Goodison Park site. The Goodison Road Stand is also home to the conference and hospitality facilities. On non-match days Goodison Park holds conferences, weddings, meetings and parties on a daily basis.

Bullens Road[edit]

On the east side of the ground, the Bullens Road stand is divided into the Upper Bullens, Lower Bullens and The Paddock. The rear of the south end of the stand houses away supporters. The north corner of the stand is connected to the Gwladys Street Stand. The current capacity of the stand is 10,546.[citation needed] The stand takes its name from the adjacent Bullens Road. The Upper Bullens is decorated with Archibald Leitch’s distinctive truss design.[47]

Howard Kendall Gwladys Street End[edit]

Behind the goal at the north end of Goodison Park, the Gwladys Street Stand is divided into Upper Gwladys and Lower Gwladys. This stand is the «Popular End», holding the most boisterous and vociferous home supporters. It is known colloquially as «The Street End». If Everton win the toss before kick-off the captain traditionally elects to play towards the Gwladys Street End in the second half. The stand has a capacity of 10,611[citation needed] and gives its name to Gwladys Street’s Hall of Fame. In July 2016 the stand was renamed the Howard Kendall Gwladys Street End, in honour of Everton’s most successful manager.[48]

Sir Philip Carter Park Stand[edit]

At the south end of the ground, behind one goal, the Park End Stand backs onto Walton Lane which borders Stanley Park. The name of the stand was originally the Stanley Park End but it is commonly referred to as the Park End. The single tiered stand broke from the multi-tiered tradition of Goodison Park. The Park End has the smallest capacity at Goodison Park. The current layout of the stand was opened on 17 September 1994 with a capacity of 5,750.[citation needed] It was opened by David Hunt, a Member of Parliament.[29] During the structure’s development, fans were able to watch matches by climbing trees in neighbouring Stanley Park.[49]

In the late 1970s and 1980s the stand accommodated the away fans. Previously it was open to home supporters. The lower tier of the old stand was terracing and this was closed off by the turn of the 1980s due to it being a fire hazard as the terracing steps were wooden. The front concrete terracing remained and was one of the last standing areas at a Premiership ground.

During the 1960s and 1970s, both ends of the ground featured a large arc behind the goals. This was created as a requirement for the 1966 World Cup because the crowd had to be a required distance from the goals.

The area around Goodison Park when built was a dense area full of terraced housing, and Goodison Avenue behind the Park End stand was no different. Oddly housing was built right into the stand itself (as shown on old photographs of Goodison and in programmes). The club had previously owned many of the houses on the road and rented them to players. One of the players to live there, Dixie Dean later had a statue erected in his honour near the Park End on Walton Lane.[11]

By the 1990s the club had demolished virtually the whole street and this coincided with the redevelopment of the Park End stand. However at present the majority of the land is now an open car park for the club and its Marquee.

In July 2016 the stand was renamed the Sir Philip Carter Park Stand, in honour of the club’s former chairman.[48]

St Luke’s Church[edit]

Sketch published by Outdoors Magazine in 1892, St. Luke’s predecessor – a wooden church structure can be seen behind the corner of the pitch.

Goodison Park is unique in the sense that a church, St Luke’s, protrudes into the site between the Goodison Road Stand and the Gwladys Street Stand only yards from the corner flag. Everton do not play early kick-offs on Sundays in order to permit Sunday services at the church.[50] The church is synonymous with the football club and a wooden church structure was in place when Goodison Park was originally built. Former Everton players such as Brian Harris have had their funeral service held there.[51]

The church can be seen from the Park End and Bullens Road and has featured prominently over the years as a backdrop during live televised matches. It is also the home to the Everton Former Players’ Foundation of which the Reverend is a trustee.[52]

The church has over the years curtailed development of the ground. Everton did attempt to pay for its removal in order to gain extra space for a larger capacity.[29] One of two jumbotron screens (both installed in 2000) has been installed between the Goodison Road stand and Gwladys Street stand[29] partially obscuring the church from view. The other is situated between the Bullens Road and Park End.[53]

Imaginative spectators would climb the church and watch a football game from the rooftop however they have now been deterred from doing so with the installation of security measures such as barbed wire and anti-climb paint. In addition, the introduction of the ‘all-seater’ ruling following the Taylor Report has meant that spectators no longer resort to climbing nearby buildings for a glimpse of the event as a seat is guaranteed with a purchased ticket.

The future[edit]

Following the conversion of Goodison Park into an all-seater stadium in 1994, plans for relocation to a new site have been afoot since 1996, when then chairman Peter Johnson announced his intention to build a new 60,000-seat stadium for the club. At the time, no English league club had a stadium with such a high capacity.[54]

In January 2001,[55] plans were drawn up to move to a 55,000-seat purpose-built arena on the site of the King’s Dock in Liverpool. The proposed stadium would have had a retractable roof enabling it to be used for concerts and chairman Bill Kenwright had hoped to have it ready for the 2005–06 season.[56]

However, the plans were abandoned in April 2003 due to the club not being able to raise adequate funds.[57] Following this, plans were made to move to Kirkby, just outside the city, in a joint venture with the supermarket chain Tesco.[58] The scheme was greatly divisive amongst supporters and local authorities,[59] but was rejected in late November 2009 following a decision by Secretary of State for Communities and Local Government.[60]

The site of Goodison Park was earmarked in 1997[61] and 2003[62] for a food store by Tesco who offered £12 million which was valued at £4 million[62] for the site but Liverpool City Council’s advisor’s advised against allowing planning permission.[63] The club were advised that the planning permission required would not necessarily be granted, and chose not to take the scheme further.[64]

Supporters’ groups have fought against the club moving to a new stadium twice. In 2007 a group was established called Keep Everton in Our City (KEIOC) whose aim is to keep Everton FC inside the city of Liverpool. The KEIOC attempted to prevent the club moving to a new stadium in Kirkby, just outside the city limits.[65] The supporters’ groups have argued that it is possible to expand Goodison Park, despite the odd shaped landlocked site being surrounded by housing, local authority buildings, and have produced image renders, architectural drawings and costings for a redeveloped Goodison Park.[66] The then Liverpool City Council leader Warren Bradley stated in November 2009 that a redevelopment of Goodison Park was his favoured option, and that relocation of the homes, infrastructure and businesses in streets adjoining the ground is «not a major hurdle». Council leader Joe Anderson stated, «the setback for Everton was an opportunity for both clubs to go back to the drawing board».[67]

Everton were considering all options, including relocation, redevelopment of the current ground, or a groundshare with Liverpool F.C., in a new, purpose-built stadium in Stanley Park, stressing that finance is the main factor affecting decision-making.[68]

In 2010, Everton supporters approached University of Liverpool and Liverpool City Council to initiate a dedicated ‘Football Quarter’/’Sports City’ zone around Goodison Park, Stanley Park and Anfield. The university and city council met with the North West Development Agency, Everton and Liverpool F.C. representatives but no further action was taken.[69] Plans for relocation of Liverpool to a new stadium have since been abandoned in favour of expanding Anfield.

On 10 February 2011, Liverpool City Council Regeneration and Transport Select Committee proposed to open the eastern section of the Liverpool Outer Loop line using «Liverpool Football Club and Everton Football Club as priorities, as economic enablers of the project».[70] This proposal would place both football clubs on a rapid-transit Merseyrail line circling the city giving high throughput, fast transport access.

In 2016, following his investment in the club by major shareholder Farhad Moshiri, the prospect of a new stadium was once again addressed, with a pair of options mentioned. The preferred option was to resurrect the idea of a riverside stadium, this time in partnership with the Peel Group using the Clarence Dock. However, the other option was a site located at Stonebridge Cross in Gillmoss, which is seen as more easily deliverable in some areas.[71] The dockside site option was later confirmed as Bramley-Moore Dock.[72]

Walton Lane development[edit]

In August 2010, Everton announced plans to build a new development situated between the Park End stand and Walton Lane; the site is currently used for a hospitality marquee.[73] The £9m scheme was designed by Manchester-based Formroom Architects.[74] In September 2010 the club submitted a planning application to Liverpool City Council.[75]

The proposed development is a four-storey building which include a retail store, ticket office, offices, conference and catering facilities and a museum. The project has been delayed twice and is currently on hold.[citation needed]

Goodison Park Legacy project[edit]

In February 2021, Liverpool City Council voted in favour of Everton’s £82m plan to redevelop Goodison Park into a mixed-use scheme featuring 173 homes and 51,000sq ft of offices. The approval followed the green light for the club’s new Everton Stadium, which is now under construction and due to complete in 2024.

As well as the homes and office space, the outline proposals for the Goodison Park site in Walton comprise a 63,000 sq ft, six-storey care home, more than 107,000 sq ft of space for community uses, and 8,000 sq ft of retail and leisure space.[76]

Transport[edit]

Goodison Park is located two miles (3 km) north of Liverpool City Centre. Liverpool Lime Street railway station is the nearest mainline station. The nearest station to the stadium is Kirkdale railway station on the Merseyrail Northern Line which is located just over half a mile (800 m) away. On match days there is also a frequent shuttle bus service from Sandhills railway station known as «SoccerBus». In 2007 Sandhills underwent a £6million renovation to help encourage people to use the rail service.[77]

Walton & Anfield railway station located on Walton Lane—the same road that the Park End backs onto—was the nearest station to Goodison Park until its closure in 1948.[78] Although Everton has now shifted towards a new stadium away from Goodison Park it remained a suggestion that the station could be re-opened should the freight only Canada Dock Branch line once again run passenger trains.[79]

There are on-site parking facilities for supporters (limited to 230 spaces)[53] and the streets surrounding the ground allow parking only for residents with permits. The Car Parking resident parking scheme is operated by Liverpool City Council.[80]

Records[edit]

Everton has staged more top-flight football games than any other club in England, eight more seasons than second placed Aston Villa. Everton have played at Goodison Park for all but 4 of their 106 league seasons, giving Goodison Park the distinction of hosting more top-flight games than any other ground in England.[2] Goodison is the only English club ground to have hosted a FIFA World Cup semi final. Until the expansion of Old Trafford in 1996 Goodison Park held the record Sunday attendance on a Football League ground (53,509 v West Bromwich Albion, FA Cup, 1974).

Everton won 15 home league games in a row between 4 October 1930 and 4 April 1931.[81] In the 1931–32 season Goodison Park was the venue of the most goals scored at home in a league season, 84 by Everton.[7] Between 23 April 1984 and 2 September 1986 Everton scored consecutively in 47 games.,[81] registering 36 wins and 7 draws and scoring 123 goals in the process while conceding 38. Scottish striker Graeme Sharp scored 32 of these goals.[7]

Jack Southworth holds the record for most goals scored in one game at Goodison Park, scoring six versus West Bromwich Albion on 30 December 1893.[21]

The most goals scored in a game at Goodison Park is 12, this occurred in two Everton games; versus Sheffield Wednesday (9–3) on 17 October 1931 and versus Plymouth Argyle (8–4) on 27 February 1954.[81]

Attendances[edit]

Average yearly attendance for Goodison Park

Whilst at Goodison Park the club has had one of the highest average attendances in the country. The stadium has only had six seasons where Everton FC has not been amongst the top ten highest attendances in the country.[82]

The highest average attendance in the club’s history has been 51,603 (1962–63) and the lowest was 13,230 (1892–93) which was recorded in Goodison Park’s first year.[83]

The five highest attendances for Everton at Goodison Park are:

| Date | Competition | Opposition | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 18 September 1948 | Division One | Liverpool | 78,299 |

| 14 February 1953 | FA Cup | Manchester United | 77,920 |

| 28 August 1954 | Division One | Preston North End | 76,839 |

| 29 January 1958 | FA Cup | Blackburn Rovers | 75,818 |

| 27 December 1954 | Division One | Wolverhampton Wanderers | 75,322 |

Source:[84]

The five lowest attendances for Everton at Goodison Park are:

| Date | Competition | Opposition | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20 December 1988 | Simod Cup | Millwall | 3,703 |

| 1 October 1991 | Zenith Data Systems Cup | Oldham | 4,588 |

| 22 January 1991 | Sunderland | 4,609 | |

| 16 February 1988 | Simod Cup | Luton | 5,204 |

| 28 February 1989 | Q.P.R. | 7,072 |

Source:[85]

Other uses[edit]

Despite being purposefully built for Everton F.C. to play football,[86] Goodison Park has hosted many other types of events.

Goodison Park as host stadium for football[edit]

Goodison Park became the first Football League ground to hold an FA Cup Final, in 1894. Notts County beat Bolton Wanderers, watched by crowd of 37,000. An FA Cup final replay was staged in 1910 with Newcastle United beating Barnsley 2–0.

On 26 December 1920, Goodison Park hosted a match between; Dick, Kerr’s Ladies & St Helens Ladies. An estimated 53,000 attended the match,[87] at a time when the average gate at Goodison Park in 1919–20 was near 29,000.[88] Dick, Kerr’s Ladies won 4–0. More than £3,000 was raised for charity. Shortly after, the Football Association banned women’s football. The reasons given by the FA were not substantial and it is perceived by some that the women’s teams were a threat to the men’s game.[89] The ban was lifted in 1970.[87]

During the Second World War, Goodison Park was chosen as a host venue for the «Football League – Northern Section».[90]

In 1949, Goodison Park became the site of England’s first ever defeat on English soil by a non-Home Nations country, namely the Republic of Ireland. The ground hosted five matches including a semi-final for the 1966 FIFA World Cup. In April 1895 Goodison Park hosted England versus Scotland[91] and so Everton became the first club to host England internationals on two grounds (the other being Anfield in 1889 when England won 6–2 versus Ireland[92]). The city of Liverpool also became the first English city to stage England games at three different venues, the other being Aigburth Cricket Club.

In 1973 Goodison hosted Northern Ireland’s home games against Wales and England.[93]

1966 FIFA World Cup[edit]

Goodison Park hosted five games during the 1966 FIFA World Cup. The original schedule of the 1966 World Cup meant that if England won their group and then reached the Semi final, the match would be held at Goodison Park. However, the organising committee were allowed to swap the venues, with England playing Portugal at Wembley Stadium.[94]

Group stage[edit]

Quarter-finals[edit]

Semi-finals[edit]

Portugal’s Eusébio won the tournament’s Golden Boot scoring nine goals, six of them at Goodison Park.[95] Eusébio later stated that «Goodison Park is for me the best stadium in my life».[96] In Garrincha’s 50 caps for Brazil, the only defeat he experienced was in the game versus Hungary at Goodison Park.[97]

FA Cup Final[edit]

Two years after construction, Goodison Park was chosen by the Football Association to host the final of the FA Cup.

| Year | Attendance | Winner | Runner-up | Details | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 March 1894 | 37,000 | Notts County | 4 | Bolton Wanderers | 1 | [29] |

British Home championships[edit]

England[edit]

Goodison Park has played host to England on eight occasions during the Home Championships. When Everton player Alex Stevenson scored for Ireland in the 1935 British Home Championship versus England, he became the first player to score an international away goal on his club’s home ground.[98]

| Date | «Home» Team | «Away» Team | Details | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 April 1895 | England | 3 | Scotland | 0 | [91] |

| 16 February 1907 | 1 | Ireland | 0 | [99] | |

| 1 April 1911 | 1 | Scotland | 1 | [100] | |

| 22 October 1924 | 3 | Ireland | 0 | [101] | |

| 22 October 1928 | 2 | 1 | [102] | ||

| 6 February 1935 | 2 | 1 | [103] | ||

| 5 November 1947 | 2 | Ireland | 2 | [104] | |

| 11 November 1953 | 3 | Northern Ireland | 1 | [105] |

Northern Ireland[edit]

On 22 February 1973 the Irish Football Association announced that Northern Ireland’s home matches in the 1973 British Home Championship would be moved to Goodison Park due to the civil unrest within Belfast at that time.[93]

| Date | «Home» Team | «Away» Team | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 May 1973 | Northern Ireland | 1 | England | 2 |

| 19 May 1973 | 1 | Wales | 0 |

Both Northern Ireland goalscorers Dave Clements (vs. England) and Bryan Hamilton (vs. Wales)[106] went on to play for Goodison Park’s club side Everton later on in their careers.

Other neutral matches at Goodison Park[edit]

| Date | Competition | «Home» Team | «Away» Team | Details | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 April 1894 | Inter-League Match | Football League XI | 1 | Scottish League XI | 1 | [107] |

| 21 March 1896 | FA Cup Semi final | Bolton Wanderers | 1 | Sheffield Wednesday | 1 | [108] |

| 11 April 1896 | Inter League Match | Football League XI | 5 | Scottish League XI | 1 | [107] |

| 21 March 1903 | FA Cup Semi final | Bury | 3 | Aston Villa | 0 | [109] |

| 13 March 1904 | Manchester City | 3 | Sheffield Wednesday | 0 | [110] | |

| 28 April 1910 | FA Cup Final (Replay) | Newcastle United | 2 | Barnsley | 0 | [111] |

| 1 April 1914 | FA Cup Semi final Replay | Burnley | 1 | Sheffield United | 0 | [112] |

| 14 March 1925 | Inter-League Match | Football League XI | 4 | Scottish League XI | 3 | [107] |

| 26 March 1928 | FA Cup Semi final Replay | Huddersfield Town | 0 | Sheffield United | 0 | [113] |

| 25 September 1929 | Inter-League Match | Football League XI | 7 | Irish League XI | 2 | [114] |

| 3 December 1934 | FA Cup 1st round, 2nd replay | New Brighton | 2 | Southport | 1 | [115] |

| 11 May 1935[nb 2] | Inter-League Match | Football League XI | 10 | Welsh Football League/Irish league XI | 2 | [116] |

| 21 October 1936 | 2 | Scottish League XI | 0 | [107] | ||

| 4 November 1939[nb 3] | Representative Match | 3 | All British XI | 3 | [117] | |

| 19 February 1947 | Inter-League Match | 4 | Irish League XI | 2 | [114] | |

| 24 January 1948[nb 4] | FA Cup 4th round | Manchester United (home team) | 3 | Liverpool | 0 | [118] |

| 2 April 1949 | FA Cup Semi final Replay | Wolverhampton Wanderers | 1 | Manchester United | 0 | [119] |

| 21 September 1949[nb 5] | Friendly International | England | 0 | Republic of Ireland | 2 | [120] |

| 14 March 1951 | FA Cup Semi final Replay | Blackpool | 2 | Birmingham City | 1 | [121] |

| 19 May 1951 | Friendly International | England | 5 | Portugal | 2 | [122] |

| 10 October 1951 | Inter-League Match | Football League XI | 9 | League of Ireland XI | 1 | [123] |

| 7 December 1955 | Inter-League Match | 5 | 1 | [124] | ||

| 15 January 1958 | U23 International | England U23 | 3 | Scotland U23 | 1 | [125] |

| 23 September 1959 | England U23 | 0 | Hungary U23 | 1 | [125] | |

| 8 February 1961 | England U23 | 2 | Wales U23 | 0 | [125] | |

| 17 August 1963 | FA Charity Shield | Everton | 4 | Manchester United | 0 | [126] |

| 5 January 1966[nb 6] | Friendly International | England | 1 | Poland | 1 | [127] |

| 13 August 1966 | FA Charity Shield | Everton | 0 | Liverpool | 1 | [126] |

| 1 May 1968 | U23 International | England U23 | 4 | Hungary U23 | 0 | [125] |

| 30 November 1970 | FA Cup 1st round, 2nd replay | Tranmere Rovers | 0 | Scunthorpe United | 1 | [128] |

| 19 April 1972 | FA Cup Semi final Replay | Arsenal | 2 | Stoke City | 1 | [129] |

| 18 March 1974[nb 7] | FA Cup 6th round replay | Newcastle United | 0 | Nottingham Forest | 0 | [130] |

| 21 March 1974 | FA Cup 6th round, 2nd replay | Nottingham Forest | 0 | Newcastle United | 1 | [130] |

| 4 April 1979 | FA Cup Semi final replay | Manchester United | 1 | Liverpool | 0 | [131] |

| 17 May 1983 | UEFA U18 Championship Finals Group A | West Germany U18 | 3 | Bulgaria U18 | 1 | [132] |

| 13 April 1985 | FA Cup Semi final | Manchester United | 2 | Liverpool | 2 | [133] |

| 6 April 1989 | U18 International | England U18 | 0 | Switzerland U18 | 0 | [134] |

| 17 January 1991 | FA Cup 3rd Round | Woking (home team) | 0 | Everton | 1 | [135] |

| 13 November 1993 | FA Cup 1st round | Knowsley United | 1 | Carlisle United | 4 | [136] |

| 6 June 1995 | Umbro Cup | Brazil | 3 | Japan | 0 | [137] |

| 9 September 2003 | UEFA U21 Championship Qualifying | England U21 | 1 | Portugal U21 | 1 | [138] |

Non-football usage[edit]

Men in dark blue and white suits stand across the pitch in formation, creating the image of a Union Flag. 80,000 people attended Goodison Park to see King George V.

On 11 July 1913 Goodison Park became the first English football ground to be visited by a reigning monarch when King George V and Queen Mary attended.[139] The attending royals had opened Gladstone Dock on the same day.[140] A tablet was unveiled in the Main Stand to mark the occasion. During the First World War Goodison frequently hosted Territorial Army training drill sessions.[29]

On 19 May 1938 George VI and Queen Elizabeth attended Goodison Park to present new colours to the 5th Battalion the King’s Regiment (Liverpool) and the Liverpool Scottish (Queens Own Cameron Highlanders) in front of 80,000 spectators.[141]

In 1921, Goodison Park played host to Lancashire’s rugby team when they took on Australia national rugby union team and lost 29–6.[142]

Goodison Park was chosen as one of two English venues for the Sox-Giants 1924 World Tour. On 23 October 1924, 2,000 spectators witnessed US baseball teams Chicago White Sox and New York Giants participate in an exhibition match. One player managed to hit a ball clear over the large Goodison Road Stand. The other English venue selected was Stamford Bridge.[143]

In September 1939, Goodison Park was commandeered by military, the club’s minutes read: «The Chairman reported that our ground has been commandeered as an anti-aircraft (Balloon Barrage section), post.»[144] During World War Two, an American forces baseball league was based at Goodison Park.[145] In addition, a baseball game between two Army Air Force nines watched by over 8,000 spectators raised over $3,000 for British Red Cross and St. John’s Ambulance fund.[146]

The Liverpool Trojans and Formby Cardinals were the last two teams to play baseball at Goodison Park. This was in the Lancashire Cup Final in 1948.[147]

Goodison Park is used as a venue for weddings.[148] More than 800 fans’ ashes have been buried at Goodison Park and since 2004 the club have had to reject further requests because there is no room for any more.[149] Tommy Lawton wanted his ashes to be scattered at Goodison but his son chose to donate them to the national football museum because of Goodison’s uncertain future.[150]

Goodison Park was also the venue for the boxing match between «Pretty» Ricky Conlan (played by native Evertonian and Everton fan Tony Bellew) and Adonis Creed (Michael B. Jordan) in the 2015 movie Creed.[151] The stadium hosted the first outdoor boxing event in Liverpool since 1949 when Bellew defeated Ilunga Makabu on 29 May 2016 to claim the vacant WBC Cruiserweight title.[152][153]

Rugby League at Goodison Park[edit]

Between 1908 and 1921, Goodison Park also played host to four rugby league Kangaroo Tour matches involving the Australian and Australasian teams from 1908 to 1921.[154]

| Game | Date | Host team | Result | Touring team | Attendance | Tour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18 November 1908 | 9–10 | 6,000 | 1908–09 Kangaroo tour of Great Britain | ||

| 2 | 3 March 1909 | 14–7 | 4,500 | |||

| 3 | 25 October 1911 | 3–16 | 6,000 | 1911–12 Kangaroo tour of Great Britain | ||

| 4 | 30 November 1921 | 6–29 | 17,000 | 1921–22 Kangaroo tour of Great Britain |

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ This is the original cost of the ground. Further costly developments have occurred since.

- ^ This was one of two matches which trialled having two referees in a single match. The other trial was on 8 May 1935 when the Football League team beat West Bromwich Albion 9–6 at The Hawthorns.

- ^ The game took place to aid the Red Cross fund.

- ^ Due to war damage, Old Trafford was closed at the time, and Manchester United were playing their home matches at Maine Road. However, on the same day, Manchester City were at home to Chelsea in another FA Cup tie and as a result this tie was switched to Goodison Park.

- ^ This was the first time that England had been beaten at home by a team from outside the Home Nations.

- ^ England’s goal was scored by Bobby Moore. This was his first international goal and the only one on English soil. Ray Wilson was chosen to play in this game, he is therefore the last Everton player to play for England at Goodison Park.

- ^ Due to a pitch invasion at the original match (which Newcastle United won 4–3), The FA ordered the tie to be replayed at a neutral venue.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c «Premier League Handbook 2020/21» (PDF). Premier League. p. 16. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ^ a b «England – First Level All-Time Tables 1888/89-2008/09». RSSSF. Archived from the original on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Inglis, Simon (1996). The Football Grounds of Britain. CollinsWillow. ISBN 0-00-218426-5.

- ^ «I: The Early Days (1878–88)». ToffeeWeb. Archived from the original on 15 February 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2007.

- ^ «History of the Football League». The Football League. 3 August 2008. Archived from the original on 9 February 2009. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ «The Everton Story 1878–1930». Everton F.C. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ a b c «General Trivia». ToffeeWeb. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ a b c d «Liverpool Football Club is formed». Liverpool F.C. Archived from the original on 12 July 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ Kennedy, David; Collins, Michael (2006). «Community Politics in Liverpool and the Governance of Professional Football in the Late Nineteenth Century». The Historical Journal. Cambridge University Press. 49 (3): 761–788. doi:10.1017/s0018246x06005504. S2CID 154635435.

- ^ «1878–1930 – Early homes». Everton F.C. Archived from the original on 28 November 2012. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Corbett, James (2003). School of Science. Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4050-3431-9.

- ^ a b c d MacDonald, Ian (16 December 2008). «And If You Know Your History». ToffeeWeb. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «From Anfield to Goodison». ToffeeWeb. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «Anfield Split – The Move to Goodison». evertoncollection.org.uk. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «The Everton club». Liverpool Daily Post. 19 March 1892.

- ^ Kennedy, David (2006). «Community Politics in Liverpool and the Governance of Professional Football in the Late Nineteenth Century». The Historical Journal. Cambridge University Press. 49 (3): 761–788. doi:10.1017/s0018246x06005504. S2CID 154635435.

- ^ Birley, Derek (1995). Land of sport and glory: sport and British society, 1887–1910. Manchester: Manchester University Press. p. 40. ISBN 0-7190-4494-4.

- ^ Inglis, Simon (2005). Engineering Archie: Archibald Leitch – Football Ground Designer. English Heritage. ISBN 1-85074-918-3.

- ^ «The Move to Goodison». Everton Collection. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ a b c «History of Goodison Park». ToffeeWeb. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Rogers, Ken (1992). Goodison Glory. Breedon Sports. p. 222. ISBN 1-873626-11-8.

- ^ «Minute book». evertoncollection.org.u. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ «History of Liverpool». Liverpool in Pictures. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ Conn, David (4 November 1999). Goodison Conundrum. The Independent.

- ^ The verton Story, Gordon Hodgson, Page 20, 1985

- ^ «Past Presidents». The Liverpool Architectural Society. Archived from the original on 4 October 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ Liverpool Echo. September 1909.

- ^ «RMS Mauretania». Ocean-liners.com. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i «History of Goodison Park». Everton F.C. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ Everton Board Minutes. Everton F.C. 21 September 1941.

- ^ «Goodison Park records». ToffeeWeb. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ Redmond, Phil (26 August 2004). «When Everton were Mersey millionaires». icliverpool. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ a b Shennan, Paddy (3 July 2004). «Paddy Shennan: Golden Vision». Liverpool Echo.

- ^ «Everton Results». evertonresults.net. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ «Everton firsts». Everton F.C. Archived from the original on 20 August 2006. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ «Everton 8 v Southampton 0». art247. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ Green, Geoffrey (21 December 1970). «Ruthless defensive efficiency». The Times.

- ^ «Anfield history». Anfield Reds. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ Berry, Mick (28 December 1996). «Football: Fan’s Eye View No 198 Everton». The Independent. London. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- ^ O’hagan, Simon (27 February 1994). «Wary cross the Mersey». The Independent. London. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ «Dixie Dean». mirrorfootball.co.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ «Harry Catterick». mirrorfootball.co.uk. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ «Programme – Everton v Borussia Monchengladbach». evertoncollection.org.uk. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Commemorative medal – Centenary of Goodison Park, 1892–1992». evertoncollection.org.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Fact Sheet 2: Football Stadia After Taylor». University of Leicester: Department of Sociology. March 2002. Retrieved 6 January 2010.

- ^ «History of Goodison Park». Everton F.C. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ Inglis, Simon (2005). Engineering Archive. ISBN 978-1-85074-918-9.

- ^ a b «Stands Renaming Honours Greats». Everton F.C. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ Shaw, Paul (25 April 1994). «Bad weather gathering over Goodison Park». The Independent.

- ^ «Everton obey holy orders». BBC. February 2002. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ «Brian Harris: Fun-loving Everton footballer». The Independent. London. 21 February 2008. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ «Patrons and Trustees». Everton F.C. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ a b «Goodison Park Stadium Redevelopment» (PDF). Savills, KSS Design and Franklin Sports Business. October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ «Match Report: Everton v Chelsea 1996–97». Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2010.

- ^ «Everton reveal stadium blueprint». BBC News. 22 January 2001.

- ^ «Everton’s grounds for hope». BBC News. 24 July 2001.

- ^ Everton fail in King’s Dock bid, BBC Sport, 11 April 2003, retrieved 17 December 2009

- ^ «Everton in talks on stadium move». BBC News. 15 June 2006. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ «Everton stadium plans ‘are wrong’«. BBC News. 18 November 2008. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ «Government reject Everton’s Kirkby stadium plans». BBC Sport. 26 November 2009. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ Dunn, Andy (30 November 1997). «Goodison To Be A Tesco». The People.

- ^ a b Gleeson, Bill (1 November 2002). «NEW KINGS DOCK HITCH FOR BLUES; Club warned of concerns over Goodison shopping centre plans». Liverpool Daily Post.

- ^ «District and local centre study» (PDF). Liverpool City Council. Retrieved 16 December 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ «New Kings Dock Hitch For Blues». Ellesmere Port Pioneer. Trinity Mirror. 1 November 2002. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ «New Everton stadium battle lines drawn». evertonbanter.co.uk (Trinity Mirror). 18 November 2008. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ Reade, Brian (27 November 2009). «Why Everton dodged a bullet over Kirkby stadium». Mirror Football. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ^ Bartlett, David (27 November 2009). «Kirkby refusal for Everton forces ground share re-think». Liverpool Daily Post. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ^ «Elstone on ‘no’ decision». Everton F.C. 26 November 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ^ Randles, David (13 March 2010). «Liverpool FC and Everton FC fans’ groups unite to promote city football quarter». Liverpool Daily Post. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ «Liverpool City Council Regeneration and Transport Select Committee meeting on 10.02.2011». Archived from the original on 12 January 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- ^ O’Keefe, Greg (22 July 2016). «Blues challenge is to deliver the docks – but a Plan B is shrewd». Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ «Everton reveal Bramley Moore Dock as preferred stadium site». BBC News. 5 January 2017.

- ^ «Blues unveil plans». Everton F.C. 4 August 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ Winston, Anna (6 August 2010). «Formroom designs £9 million project for Everton». BD Online. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- ^ «Blues submit plans». Everton F.C. 22 September 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- ^ «Goodison Park legacy project back in spotlight». Place North West. 25 April 2022. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ «Sandhill Station shuts for 4 months». Liverpool Echo. 9 November 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ «Walton and Anfield railway station». subbrit.org.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ «Merseytravel» (PDF). Merseytravel. 10 December 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 August 2011. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «Football Parking». Liverpool City Council. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ a b c «Everton records». Statto.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2010. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ «Attendance History». ToffeeWeb. Archived from the original on 9 May 2013. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ «Everton Results». evertonresults.com. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ «Everton Results». evertonresults.com. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Everton Results». evertonresults.com. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Events at Goodison». Everton F.C. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ a b Alexander, Shelley (3 June 2005). «Trail-blazers who pioneered women’s football». BBC Sport. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ «Everton Results». evertonresults.com. Retrieved 11 April 2010.

- ^ «Dick, Kerr Ladies FC 1917–1965». dickkerrladies.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «The Second World War Years». efchistory.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ a b «England FC Match Data». EnglandFC.com. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «EnglandFC Match Data». England FC. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ a b McDonald, Henry (26 July 2009). «Anger as Belfast stadium plan is revived». The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «The World Cup at Goodison Park». bluekipper.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «1966 FIFA World Cup England -Hurst the hero for England in the home of football». FIFA. Archived from the original on 24 January 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- ^ Stevenson, Jonathan (5 November 2009). «Europa League as it happened». BBC. Retrieved 16 November 2009.

- ^ «A Tribute To… Garrincha». Bleacher Report. 20 August 2008. Archived from the original on 2 March 2010. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ «Southampton vs Everton – Premiership Season 2004/05». ToffeeWeb. 6 February 2005. Archived from the original on 8 January 2010. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «England FC Match Data». EnglandFC.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «England FC Match Data». EnglandFC.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «England FC Match Data». EnglandFC.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «England FC Match Data». EnglandFC.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «England FC Match Data». EnglandFC.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «England FC Match Data». EnglandFC.com. Archived from the original on 6 July 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «England FC Match Data». EnglandFC.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «Home Internationals». Archived from the original on 24 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d «Scotland versus English Football League Complete Football Association Record». londonhearts.com. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ a b «Irish League Representative Match Results». irishleaguegreats.blogspot.com. 18 August 2008. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Association Football: The Surrey Senior Cup». The Times. 13 May 1935. p. 5.

- ^ «Football League v. All British XI». The Times. 27 October 1939. p. 3.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «England FC Match Data». EnglandFC.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «England FC Match Data». EnglandFC.com. Archived from the original on 17 January 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ «Easy Win for the Football League». The Times. 11 October 1951. p. 9.

- ^ «Football League Should Beat Ireland». The Times. 7 December 1955. p. 14.

- ^ a b «Community Shield & Charity Shield results». footballsite.co.uk. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ «EnglandFC Match Data». EnglandFC.com. Archived from the original on 29 November 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «Programme – Tranmere Rovers v Scunthorpe United». evertoncollection.org.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ a b «Fa Cup Final 1974». fa-cupfinals.co.uk. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «European U-18 Championship 1983». RSSSF. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ «Cup Competitions – Everton FC». everton-mad.co.uk. Retrieved 6 April 2010.

- ^ «Programme – England v Switzerland (Under 18’s)». evertoncollection.org.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ «Woking Football Club History». wokingfc.co.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ Metcalf, Rupert (11 November 1993). «Football / FA Cup Countdown». The Independent. London. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ «Umbro Cup 1995». RSSSF. 30 July 1999. Archived from the original on 27 August 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «England U21 Match Results». englandfootballonline.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «The Early Years of the Twentieth Century». efchistory.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ «Gladstone Dock». Mersey Gateway. Archived from the original on 7 May 2006. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ «My war with the 5th Battalion King’s Regiment». BBC. 3 October 2005.

- ^ «The Aussies win (aka Australia beat Lancashire) 1921». British Pathe. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ Bloyce, Danny (March 2008). «Baseball in England: A Case of Prolonged Cultural Resistance». Journal of Historical Sociology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 21 (1): 120–142. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6443.2008.00332.x.

- ^ «Everton board minutes: 1939–40». evertoncollection.org.uk. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Nicholson, Robert (1979). The Shell weekend guide to London and the South-East. R Nicholson. p. 55.

- ^ Bullock, Steven R. (1 March 2004). Playing for their nation: baseball and the American military during World War II. University of Nebraska Press. p. 49.

- ^ «Trojans history». liverpooltrojansbaseball.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ «Weddings at Goodison». Everton F.C. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- ^ Ward, David (16 June 2004). «Goodison Park to end fan burials». The Guardian. London. Retrieved 6 November 2009.

- ^ «Player’s Ashes Given To National Football Museum». culture24.org.uk. 9 December 2003. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ «Film Review: ‘Creed’«. 18 November 2015. Archived from the original on 5 September 2018. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ McKenna, Michael (3 May 2016). «Tony Bellew expecting Liverpool to go nuts for first stadium fight in 67 years». Liverpool Echo.

- ^ Dirs, Ben (29 May 2016). «Tony Bellew beats Ilunga Makabu at Goodison Park to win world title». BBC Sport.

- ^ «Goodison Park». Rugby League Project. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

External links[edit]

- Goodison Park at StadiumDB.com

- Goodison Park at The Everton Collection

- Goodison Park at TripAdvisor

|

«The Theatre of Dreams» |

|

|

|

|

|

| Location | Sir Matt Busby Way Old Trafford Trafford Greater Manchester England |

|---|---|

| Public transit | |

| Owner | Manchester United |

| Operator | Manchester United |

| Capacity | 74,310[1] |

| Record attendance | 76,962 (Wolverhampton Wanderers vs Grimsby Town, 25 March 1939) |

| Field size | 105 by 68 metres (114.8 yd × 74.4 yd)[2] |

| Surface | Desso GrassMaster |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | 1909 |

| Opened | 19 February 1910; 113 years ago |

| Renovated | 1941, 1946–1949, 1951, 1957, 1973, 1995–1996, 2000, 2006 |

| Construction cost | £90,000 (1909) |

| Architect | Archibald Leitch (1909) |

| Tenants | |

Manchester United F.C. (1910–present)

|

Old Trafford () is a football stadium in Old Trafford, Greater Manchester, England, and the home of Manchester United. With a capacity of 74,310[1] it is the largest club football stadium (and second-largest football stadium overall after Wembley Stadium) in the United Kingdom, and the eleventh-largest in Europe.[3] It is about 0.5 miles (800 m) from Old Trafford Cricket Ground and the adjacent tram stop.

Nicknamed «The Theatre of Dreams» by Bobby Charlton,[4] Old Trafford has been United’s home ground since 1910, although from 1941 to 1949 the club shared Maine Road with local rivals Manchester City as a result of Second World War bomb damage. Old Trafford underwent several expansions in the 1990s and 2000s, including the addition of extra tiers to the North, West and East Stands, almost returning the stadium to its original capacity of 80,000. Future expansion is likely to involve the addition of a second tier to the South Stand, which would raise the capacity to around 88,000. The stadium’s record attendance was recorded in 1939, when 76,962 spectators watched the FA Cup semi-final between Wolverhampton Wanderers and Grimsby Town.

Old Trafford has hosted an FA Cup Final, two final replays and was regularly used as a neutral venue for the competition’s semi-finals. It has also hosted England fixtures, matches at the 1966 World Cup, Euro 96 and the 2012 Summer Olympics, including women’s international football for the first time in its history, and the 2003 Champions League Final. Outside football, it has been the venue for rugby league’s annual Super League Grand Final every year except 2020, and the final of Rugby League World Cups in 2000, 2013 and 2022.

History

Construction and early years

Old Trafford’s East Stand in 2011, displaying a panorama of the stadium over the course of 100 years

Before 1902, Manchester United were known as Newton Heath, during which time they first played their football matches at North Road and then Bank Street in Clayton. However, both grounds were blighted by wretched conditions, the pitches ranging from gravel to marsh, while Bank Street suffered from clouds of fumes from its neighbouring factories.[5] Therefore, following the club’s rescue from near-bankruptcy and renaming, the new chairman John Henry Davies decided in 1909 that the Bank Street ground was not fit for a team that had recently won the First Division and FA Cup, so he donated funds for the construction of a new stadium.[6] Not one to spend money frivolously, Davies scouted around Manchester for an appropriate site, before settling on a patch of land adjacent to the Bridgewater Canal, just off the north end of the Warwick Road in Old Trafford.[7]

Designed by Scottish architect Archibald Leitch, who designed several other stadia, the ground was originally designed with a capacity of 100,000 spectators and featured seating in the south stand under cover, while the remaining three stands were left as terraces and uncovered.[8] Including the purchase of the land, the construction of the stadium was originally to have cost £60,000 all told. However, as costs began to rise, to reach the intended capacity would have cost an extra £30,000 over the original estimate and, at the suggestion of club secretary J. J. Bentley, the capacity was reduced to approximately 80,000.[9][10] Nevertheless, at a time when transfer fees were still around the £1,000 mark, the cost of construction only served to reinforce the club’s «Moneybags United» epithet, with which they had been tarred since Davies had taken over as chairman.[11]

In May 1908, Archibald Leitch wrote to the Cheshire Lines Committee (CLC) – who had a rail depot adjacent to the proposed site for the football ground – in an attempt to persuade them to subsidise construction of the grandstand alongside the railway line. The subsidy would have come to the sum of £10,000, to be paid back at the rate of £2,000 per annum for five years or half of the gate receipts for the grandstand each year until the loan was repaid. However, despite guarantees for the loan coming from the club itself and two local breweries, both chaired by club chairman John Henry Davies, the Cheshire Lines Committee turned the proposal down.[12] The CLC had planned to build a new station adjacent to the new stadium, with the promise of an anticipated £2,750 per annum in fares offsetting the £9,800 cost of building the station. The station – Trafford Park – was eventually built, but further down the line than originally planned.[7] The CLC later constructed a modest station with one timber-built platform immediately adjacent to the stadium and this opened on 21 August 1935. It was initially named United Football Ground,[13] but was renamed Old Trafford Football Ground in early 1936. It was served on match days only by a shuttle service of steam trains from Manchester Central railway station.[14] It is currently known as Manchester United Football Ground.[15]

Construction was carried out by Messrs Brameld and Smith of Manchester[16] and development was completed in late 1909. The stadium hosted its inaugural game on 19 February 1910, with United playing host to Liverpool. However, the home side were unable to provide their fans with a win to mark the occasion, as Liverpool won 4–3. A journalist at the game reported the stadium as «the most handsomest [sic], the most spacious and the most remarkable arena I have ever seen. As a football ground it is unrivalled in the world, it is an honour to Manchester and the home of a team who can do wonders when they are so disposed».[17]

Before the construction of Wembley Stadium in 1923, the FA Cup Final was hosted by a number of different grounds around England including Old Trafford.[18] The first of these was the 1911 FA Cup Final replay between Bradford City and Newcastle United, after the original tie at Crystal Palace finished as a no-score draw after extra time. Bradford won 1–0, the goal scored by Jimmy Speirs, in a match watched by 58,000 people.[19] The ground’s second FA Cup Final was the 1915 final between Sheffield United and Chelsea. Sheffield United won the match 3–0 in front of nearly 50,000 spectators, most of whom were in the military, leading to the final being nicknamed «the Khaki Cup Final».[20] On 27 December 1920, Old Trafford played host to its largest pre-Second World War attendance for a United league match, as 70,504 spectators watched the Red Devils lose 3–1 to Aston Villa.[21] The ground hosted its first international football match later that decade, when England lost 1–0 to Scotland in front of 49,429 spectators on 17 April 1926.[22][23] Unusually, the record attendance at Old Trafford is not for a Manchester United home game. Instead, on 25 March 1939, 76,962 people watched an FA Cup semi-final between Wolverhampton Wanderers and Grimsby Town.[24]

Wartime bombing

The central tunnel at Old Trafford (left) is the only surviving part of the original 1910 stadium after the stadium’s bombing in World War II. The corner tunnel (right) is now used by players on matchday.