«Tao Chi» redirects here. For the Chinese landscape painter, calligrapher and poet, see Tao Chi (painter).

The lower dantian in Taijiquan: |

|

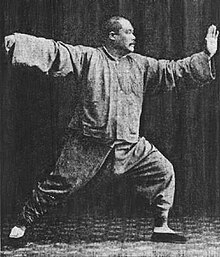

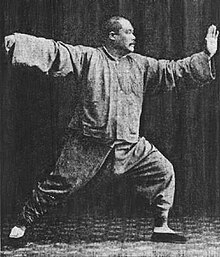

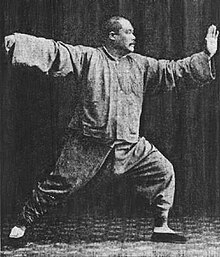

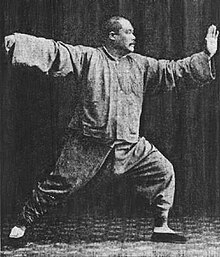

Yang Chengfu (c. 1931) in Single Whip posture of Yang-style t’ai chi ch’uan solo form |

|

| Also known as | Tàijí; T’ai chi |

|---|---|

| Focus | Chinese Taoism |

| Hardness |

|

| Country of origin | China |

| Creator | Chen Wangting or Zhang Sanfeng |

| Famous practitioners |

|

| Olympic sport | Demonstration only |

| Tai chi | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 太極拳 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 太极拳 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Taiji Boxing» | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tai chi (traditional Chinese: 太極; simplified Chinese: 太极; pinyin: Tàijí), short for Tai chi ch’üan (太極拳; 太极拳; Tàijíquán), sometimes called «shadowboxing»,[1][2][3] is an internal Chinese martial art practiced for defense training, health benefits and meditation. Tai chi has practitioners worldwide from Asia to the Americas.

Practitioners such as Yang Chengfu and Sun Lutang in the early 20th Century promoted the art for its health benefits.[4] Its global following may be attributed to overall benefit to personal health.[5] Many forms are practiced, both traditional and modern. Most modern styles trace their development to the five traditional schools: Chen, Yang, Wu (Hao), Wu, and Sun. All trace their historical origins to Chen Village.

Conceptual background[edit]

Zhou Dunyi’s Taijitu diagram which illustrates the Taijitu cosmology.

The philosophical and conceptual background to Tai chi relies on Chinese philosophy, particularly Daoist and Confucian thought as well as on the Chinese classics.[6] Early Tai Chi texts include embedded quotations from classic Chinese works like the Yijing, Great Learning, Book of History, Records of the Grand Historian, Zhu Xi, Zhou Dunyi, Mencius and Zhuangzi.[6]

Early Tai Chi sources also ground Tai Chi in the cosmology of Tai Chi ((太极, tàijí, «Supreme Polarity», or «Greatest Ultimate») from which the art gets its name. Tai Chi cosmology appears in both Taoist and Confucian philosophy, where it represents the single source or mother of yin and yang (represented by the taijitu symbol ).[7][6] Tai Chi also draws on Chinese theories of the body, particularly Daoist neidan (internal alchemy) teachings on Qi (vital energy) and on the three dantiens. Zheng Manqing emphasizes the Daoist background of Tai Chi and states that «Taijiquan enables us to reach the stage of undifferentiated pure yang, which is exactly the same as Laozi’s ‘concentrating the qi and developing softness'».[6]

As such, Tai Chi considers itself an «internal» martial art which focuses on developing the qi.[6] In China, Tai Chi is categorized under the Wudang grouping of Chinese martial arts[8]—that is, arts applied with internal power.[9] Although the term ‘Wudang’ suggests these arts originated in the Wudang Mountains, it is used only to distinguish the skills, theories and applications of neijia (internal arts) from those of the Shaolin grouping, or waijia (hard or external) styles.[10]

Tai Chi also adopts the Daoist ideals of softness overcoming hardness, of wu-wei (effortless action), and of yielding into its martial art technique, while also retaining Daoist ideas of spiritual self-cultivation.[6]

Tai Chi’s path is one of developing naturalness by relaxing, attending inward, and slowing mind, body and breath.[6] This allows us to become less tense, to drop our conditioned habits, let go of thoughts, allow qi to flow smoothly, and thus to flow with the Dao. It is thus a kind of moving meditation that allows us to let go of the self (wuwo), and experience no-mind (wuxin) and spontaneity (ziran).[6]

A key aspect of Tai Chi philosophy is to work with the flow of yin (softness) and yang (hardness) elements. When two forces push each other with equal force, neither side moves. Motion cannot occur until one side yields. Therefore, a key principle in Tai Chi is to avoid using force directly against force (hardness against hardness). Lao Tzŭ provided the archetype for this in the Tao Te Ching when he wrote, «The soft and the pliable will defeat the hard and strong.» Conversely, when in possession of leverage, one may want to use hardness to force the opponent to become soft. Traditionally, Tai Chi uses both soft and hard. Yin is said to be the mother of Yang, using soft power to create hard power.

Traditional schools also emphasize that one is expected to show wude («martial virtue/heroism»), to protect the defenseless, and show mercy to one’s opponents.[4]

Practice[edit]

Traditionally, the foundational Tai Chi practice consists of learning and practicing a specific solo forms or routines (taolu).[6] This entails learning a routine sequence of movements that emphasize a straight spine, abdominal breathing and a natural range of motion. Tai chi relies on knowing the appropriate change in response to outside forces, as well as on yielding to and redirecting an attack, rather than meeting it with opposing force.[11] Physical fitness is also seen as an important step towards effective self-defense.

There are also numerous other supporting solo practices such as:[6]

- Sitting meditation: The empty, focus and calm the mind and aid in opening the microcosmic orbit.

- Standing meditation (zhan zhuang) to raise the yang qi

- Qigong to mobilize the qi

- Acupressure massage to develop awareness of qi channels

- Traditional Chinese medicine is taught to advanced students in some traditional schools.[12]

Further training entails learning tuishou (push hands drills), sanshou (striking techniques), free sparring, grappling training, and weapons training.[6]

In the «T’ai-chi classics», writings by tai chi masters, it is noted that the physiological and kinesiological aspects of the body’s movements are characterized by the circular motion and rotation of the pelvis, based on the metaphors of the pelvis as the hub and the arms and feet as the spokes of a wheel. Furthermore, the respiration of breath is coordinated with the physical movements in a state of deep relaxation, rather than muscular tension, in order to guide the practitioners to a state of homeostasis.

Tai Chi Quan is a complete martial art system with a full range of bare-hand movement sets and weapon forms, such as Tai Chi sword and Tai Chi spear, which are based on the dynamic relationship between Yin and Yang. While Tai Chi is typified by its slow movements, many styles (including the three most popular: Yang, Wu, and Chen) have secondary, faster-paced forms. Some traditional schools teach martial applications of the postures of different forms (taolu).

Solo practices[edit]

Taolu (solo «forms») is a choreography that serves as the encyclopedia of a martial art. Tai chi is often characterized by slow movements in Taolu practice, and one of the reasons is to develop body awareness. Accurate, repeated practice of the solo routine is said to retrain posture, encourage circulation throughout students’ bodies, maintain flexibility, and familiarize students with the martial sequences implied by the forms. The traditional styles of tai chi have forms that differ in aesthetics, but share many similarities that reflect their common origin.

Solo forms (empty-hand and weapon) are catalogues of movements that are practised individually in pushing hands and martial application scenarios to prepare students for self-defense training. In most traditional schools, variations of the solo forms can be practised: fast / slow, small-circle / large-circle, square / round (different expressions of leverage through the joints), low-sitting/high-sitting (the degree to which weight-bearing knees stay bent throughout the form).

Breathing exercises; neigong (internal skill) or, more commonly, qigong (life energy cultivation) are practiced to develop qi (life energy) in coordination with physical movement and zhan zhuang (standing like a post) or combinations of the two. These were formerly taught as a separate, complementary training system. In the last 60 years they have become better known to the general public. Qigong involves coordinated movement, breath, and awareness used for health, meditation, and martial arts. While many scholars and practitioners consider tai chi to be a type of qigong,[13][14] the two are commonly seen as separate but closely related practices. Qigong plays an important role in training for tai chi. Many tai chi movements are part of qigong practice. The focus of qigong is typically more on health or meditation than martial applications. Internally the main difference is the flow of qi. In qigong, the flow of qi is held at a gate point for a moment to aid the opening and cleansing of the channels.[clarification needed] In tai chi, the flow of qi is continuous, thus allowing the development of power by the practitioner.

Partnered practice[edit]

Two students receive instruction in tuishou («pushing hands»), one of the core training exercises of t’ai-chi ch’üan.

Tai chi’s martial aspect relies on sensitivity to the opponent’s movements and center of gravity, which dictate appropriate responses. Disrupting the opponent’s center of gravity upon contact is the primary goal of the martial t’ai-chi ch’üan student.[12] The sensitivity needed to capture the center is acquired over thousands of hours of first yin (slow, repetitive, meditative, low-impact) and then later adding yang (realistic, active, fast, high-impact) martial training through taolu (forms), tuishou (pushing hands), and sanshou (sparring). Tai chi trains in three basic ranges: close, medium and long. Pushes and open-hand strikes are more common than punches, and kicks are usually to the legs and lower torso, never higher than the hip, depending on style. The fingers, fists, palms, sides of the hands, wrists, forearms, elbows, shoulders, back, hips, knees, and feet are commonly used to strike. Targets are the eyes, throat, heart, groin, and other acupressure points. Chin na, which are joint traps, locks, and breaks are also used. Most tai chi teachers expect their students to thoroughly learn defensive or neutralizing skills first, and a student must demonstrate proficiency with them before learning offensive skills.

Martial schools focus on how the energy of a strike affects the opponent. A palm strike that looks to have the same movement may be performed in such a way that it has a completely different effect on the opponent’s body. A palm strike could simply push the opponent backward, or instead be focused in such a way as to lift the opponent vertically off the ground, changing center of gravity; or it could project the force of the strike into the opponent’s body with the intent of causing internal damage.

Most development aspects are meant to be covered within the partnered practice of tuishou, and so, sanshou (sparring) is not commonly used as a method of training, although more advanced students sometimes practice by sanshou. Sanshou is more common to tournaments such as wushu tournaments.

Weapon practice[edit]

Tai chi practices involving weapons also exist. Weapons training and fencing applications often employ:

- the jian, a straight double-edged sword, practiced as taijijian;

- the dao, a heavier curved saber, sometimes called a broadsword;

- the tieshan, a folding fan, also called shan and practiced as taijishan;

- the gun, a 2 m long wooden staff and practiced as taijigun;

- the qiang, a 2 m long spear or a 4 m long lance.

More exotic weapons include:

- the large dadao and podao sabres;

- the ji, or halberd;

- the cane;

- the sheng biao, or rope dart;

- the sanjiegun, or three sectional staff;

- the feng huo lun, or wind and fire wheels;

- the lasso;

- the whip, chain whip and steel whip.

Attire and ranking[edit]

Master Yang Jun in demonstration attire that has come to be identified with tai chi

Some martial arts require students to wear a uniform during practice. In general, Tai Chi does not specify a uniform, although teachers often advocate loose, comfortable clothing and flat-soled shoes.[15][16] Modern day practitioners usually wear comfortable, loose T-shirts and trousers made from breathable natural fabrics, that allow for free movement. Despite this, T’ai-chi ch’üan has become synonymous with «t’ai-chi uniforms» or «kung fu uniforms» that usually consist of loose-fitting traditional Chinese styled trousers and a long or short-sleeved shirt, with a Mandarin collar and buttoned with Chinese frog buttons. The long-sleeved variants are referred to as Northern-style uniforms, whilst the short-sleeved, are Southern-style uniforms.

The clothing may be all white, all black, black and white, or any other colour, mostly a single solid colour or a combination of two colours: one colour for the garment and another for the binding. They are normally made from natural fabrics such as cotton or silk. They are usually worn by masters and professional practitioners during demonstrations, tournaments and other public exhibitions.

Tai chi has no standardized ranking system, except the Chinese Wushu Duan wei exam system run by the Chinese wushu association in Beijing. Most schools do not use belt rankings. Some schools present students with belts depicting rank, similar to dans in Japanese martial arts. A simple uniform element of respect and allegiance to one’s teacher and their methods and community, belts also mark hierarchy, skill, and accomplishment. During wushu tournaments, masters and grandmasters often wear «kung fu uniforms» which tend to have no belts. Wearing a belt signifying rank in such a situation would be unusual.

Seated tai chi[edit]

Seated tai chi demonstration

Traditional tai chi was developed for self-defense, but it has evolved to include a graceful form of seated exercise now used for stress reduction and other health conditions. Often described as meditation in motion, seated tai chi promotes serenity through gentle, flowing movements. Seated tai chi exercises is touted by the medical community and researchers. It is based primarily on the Yang short form, and has been adopted by the general public, medical practitioners, tai chi instructors, and the elderly. Seated forms are not a simple redesign of the yang short form. Instead, the practice attempts to preserve the integrity of the form, with its inherent logic and purpose. The synchronization of the upper body with the steps and the breathing developed over hundreds of years, and guided the transition to seated positions. Marked improvements in balance, blood pressure levels, flexibility and muscle strength, peak oxygen intake, and body fat percentages can be achieved.[17]

Etymology[edit]

Tai Chi was known as «大恒» by the Ancient Chinese. The silk version of I Ching recorded this original name. Due to the name taboo of Emperor Wen of Western Han Empire , «大恒» changed to «太極.». Sundial shadow length changes represent traditional Chinese Medicine with four elements theory instead of Confucian politician-based five elements theory.[18] In the beginning, the color white was associated with Yin, while black was associated with Yang. Confucianism uses the reverse.

The term taiji is a Chinese cosmological concept for the flux of yin and yang. ‘Quan’ means technique.

Tàijíquán and T’ai-chi ch’üan are two different transcriptions of three Chinese characters that are the written Chinese name for the art form:

| Characters | Wade–Giles | Pinyin | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 太極 | t’ai chi | tàijí | the relationship of Yin and Yang |

| 拳 | ch’üan | quán | technique |

The English language offers two spellings, one derived from Wade–Giles and the other from the Pinyin transcription. Most Westerners often shorten this name to t’ai chi (often omitting the aspirate sign—thus becoming «tai chi»). This shortened name is the same as that of the t’ai-chi philosophy. However, the Pinyin romanization is taiji. The chi in the name of the martial art is not the same as ch’i (qi 气 the «life force»). Ch’i is involved in the practice of t’ai-chi ch’üan. Although the word 极 is traditionally written chi in English, the closest pronunciation, using English sounds, to that of Standard Chinese would be jee, with j pronounced as in jump and ee pronounced as in bee. Other words exist with pronunciations in which the ch is pronounced as in champ. Thus, it is important to use the j sound. This potential for confusion suggests preferring the pinyin spelling, taiji. Most Chinese use the Pinyin version.[19]

History[edit]

Early development[edit]

Taijiquan’s formative influences came from practices undertaken in Taoist and Buddhist monasteries, such as Wudang, Shaolin and The Thousand Year Temple in Henan.[20] The early development of Tai Chi proper is connected with Henan’s Thousand Year Temple and a nexus of nearby villages: Chen Village, Tang Village, Wangbao Village, and Zhaobao Town. These villages were closely connected, shared an interest in the martial arts and many went to study at Thousand Year Temple (which was a syncretic temple with elements from the three teachings).[20] New documents from these villages, mostly dating to the 17th century, are some of the earliest sources for the practice of Taijiquan.[20]

Some traditionalists claim that Tai chi is a purely Chinese art that comes from ancient Daoism and Confucianism.[10] These schools believe that Tai chi theory and practice were formulated by Taoist monk Zhang Sanfeng in the 12th century. These stories are often filled with legendary and hagiographical content and lack historical support.[10][20]

Modern historians pointing out that the earliest reference indicating a connection between Zhang Sanfeng and martial arts is actually a 17th-century piece called Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan (1669), composed by Huang Zongxi (1610–1695).[21][6] Aside from this single source, the other claims of connections between Tai chi and Zhang Sanfeng appeared no earlier than the 19th century.[21][6] According to Douglas Wile, «there is no record of a Zhang Sanfeng in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), and there is no mention in the Ming (1368-1644) histories or hagiographies of Zhang Sanfeng of any connection between the immortal and the material arts.»[6]

Another common theory for the origin of Tai Chi is that it was created by Chen Wangting (1580–1660) while living in Chen Village (陳家溝), Henan province.[22] The other four contemporary traditional Taijiquan styles (Yang, Sun, Wu and Wu (Hao)) trace their teachings back to Chen village in the early 1800s.[23][24]

Yang Luchan (1799–1872), the founder of the popular Yang style, trained with the Chen family for 18 years before he started to teach in Beijing, which strongly suggests that his work was heavily influenced by the Chen family art. Martial arts historian Xu Zhen claimed that the Tai chi of Chen Village was influenced by the Taizu changquan style practiced at nearby Shaolin Monastery, while Tang Hao thought it was derived from a treatise by Ming dynasty general Qi Jiguang, Jixiao Xinshu («New Treatise on Military Efficiency»), which discussed several martial arts styles including Taizu changquan.[25][26]

Tai Chi appears to have received the name «Tai Chi» during the mid-19th century.[21] Imperial Court scholar Ong Tong witnessed a demonstration by Yang Luchan before Yang had established his reputation as a teacher. Afterwards Ong wrote: «Hands holding Tai chi shakes the whole world, a chest containing ultimate skill defeats a gathering of heroes.» Before this time the art may have had other names, and appears to have been generically described by outsiders as zhan quan (沾拳, «touch boxing»), Mian Quan («soft boxing») or shisan shi (十三式, «the thirteen techniques»).[27]

Standardization[edit]

Taoist practitioners practising

In 1956 the Chinese government sponsored the Chinese Sports Committee (CSC), which brought together four wushu teachers to truncate the Yang family hand form to 24 postures. This was an attempt to standardize T’ai-chi ch’üan for wushu tournaments as they wanted to create a routine that would be much less difficult to learn than the classical 88 to 108 posture solo hand forms.

Another 1950s form is the «97 movements combined t’ai-chi ch’üan form», which blends Yang, Wu, Sun, Chen, and Fu styles.

In 1976, they developed a slightly longer demonstration form that would not require the traditional forms’ memory, balance, and coordination. This became the «Combined 48 Forms» that were created by three wushu coaches, headed by Men Hui Feng. The combined forms simplified and combined classical forms from the original Chen, Yang, Wu, and Sun styles. Other competitive forms were designed to be completed within a six-minute time limit.

In the late 1980s, CSC standardized more competition forms for the four major styles as well as combined forms. These five sets of forms were created by different teams, and later approved by a committee of wushu coaches in China. These forms were named after their style: the «Chen-style national competition form» is the «56 Forms». The combined forms are «The 42-Form» or simply the «Competition Form».

In the 11th Asian Games of 1990, wushu was included as an item for competition for the first time with the 42-Form representing t’ai-chi ch’üan. The International Wushu Federation (IWUF) applied for wushu to be part of the Olympic games.[28]

Taijiquan was added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists in 2020 for China.[29]

Styles[edit]

Chinese origin[edit]

The five major styles of tai chi are named for the Chinese families who originated them:

- Chen style (陳氏) of Chen Wangting (1580–1660)

- Yang style (楊氏) of Yang Luchan (1799–1872)

- Wu Hao style (武氏) of Wu Yuxiang (1812–1880)

- Wu style (吳氏) of Wu Quanyou (1834–1902) and his son Wu Jianquan (1870–1942)

- Sun style (孫氏) of Sun Lutang (1861–1932)

The most popular is Yang, followed by Wu, Chen, Sun and Wu/Hao.[10] The styles share underlying theory, but their training differs.

Dozens of new styles, hybrid styles, and offshoots followed, although the family schools are accepted as standard by the international community. Other important styles are Zhaobao tàijíquán, a close cousin of Chen style, which is recognized by Western practitioners; Fu style, created by Fu Chen Sung, which evolved from Chen, Sun and Yang styles, and incorporates movements from Baguazhang (Pa Kua Chang)[citation needed]; and Cheng Man-ch’ing style which simplifies Yang style.

Most existing styles came from Chen style, which had been passed down as a family secret for generations. The Chen family chronicles record Chen Wangting, of the family’s 9th generation, as the inventor of what is known today as tai chi. Yang Luchan became the first person outside the family to learn tai chi. His success in fighting earned him the nickname Yang Wudi, which means «Abnormally Large», and his fame and efforts in teaching greatly contributed to the subsequent spreading of tai chi knowledge.[citation needed]

The designation internal or neijia martial arts is also used to broadly distinguish what are known as external or waijia styles based on Shaolinquan styles, although that distinction may be disputed by modern schools. In this broad sense, all styles of t’ai chi, as well as related arts such as Baguazhang and Xingyiquan, are, therefore, considered to be «soft» or «internal» martial arts.

United States[edit]

Choy Hok Pang, a disciple of Yang Chengfu, was the first known proponent of tai chi to openly teach in the United States, beginning in 1939. His son and student Choy Kam Man emigrated to San Francisco from Hong Kong in 1949 to teach t’ai-chi ch’üan in Chinatown. Choy Kam Man taught until he died in 1994.[30][31]

Sophia Delza, a professional dancer and student of Ma Yueliang, performed the first known public demonstration of tai chi in the United States at the New York City Museum of Modern Art in 1954. She wrote the first English language book on t’ai-chi, «T’ai-chi ch’üan: Body and Mind in Harmony», in 1961. She taught regular classes at Carnegie Hall, the Actors Studio, and the United Nations.[32][33]

Zheng Manqing/Cheng Man-ch’ing, who opened his school Shr Jung t’ai-chi after he moved to New York from Taiwan in 1964. Unlike the older generation of practitioners, Zheng was cultured and educated in American ways,[clarification needed] and thus was able to transcribe Yang’s dictation into a written manuscript that became the de facto manual for Yang style. Zheng felt Yang’s traditional 108-movement form was unnecessarily long and repetitive, which makes it difficult to learn.[citation needed] He thus created a shortened 37-movement version that he taught in his schools. Zheng’s form became the dominant form in the eastern United States until other teachers immigrated in larger numbers in the 1990s. He taught until his death in 1975.[34]

United Kingdom[edit]

Norwegian Pytt Geddes was the first European to teach tai chi in Britain, holding classes at The Place in London in the early 1960s. She had first encountered tai chi in Shanghai in 1948, and studied with Choy Hok Pang and his son Choy Kam Man (who both also taught in the United States) while living in Hong Kong in the late 1950s.[35]

Lineage[edit]

Note:

- This lineage tree is not comprehensive, but depicts those considered the «gate-keepers» and most recognised individuals in each generation of the respective styles.

- Although many styles were passed down to respective descendants of the same family, the lineage focused on is that of the martial art and its main styles, not necessarily that of the families.

- Each (coloured) style depicted below has a lineage tree on its respective article page that is focused on that specific style, showing a greater insight into the highly significant individuals in its lineage.

- Names denoted by an asterisk are legendary or semi-legendary figures in the lineage; while their involvement in the lineage is accepted by most of the major schools, it is not independently verifiable from known historical records.

- v

- t

- e

Modern forms[edit]

The Cheng Man-ch’ing (Zheng Manqing) and Chinese Sports Commission short forms are derived from Yang family forms, but neither is recognized as Yang family tai chi by standard-bearing Yang family teachers. The Chen, Yang, and Wu families promote their own shortened demonstration forms for competitive purposes.

| (杨澄甫) Yang Chengfu 1883–1936 3rd gen. Yang Yang Big Frame |

||||||||

| (郑曼青) Zheng Manqing 1902–1975 4th gen. Yang Short (37) Form |

Chinese Sports Commission 1956 Beijing (24) Form |

|||||||

| 1989 42 Competition Form (Wushu competition form combined from Chen, Yang, Wu & Sun styles) |

||||||||

Purposes[edit]

The primary purposes of tai chi are health, sport/self-defense and aesthetics.

Practitioners mostly interested in tai chi’s health benefits diverged from those who emphasize self-defense, and also those who attracted by its aesthetic appeal (wushu).

More traditional practitioners hold that the two aspects of health and martial arts make up the art’s yin and yang. The «family» schools present their teachings in a martial art context, whatever the intention of their students.[36]

Health[edit]

Tai chi’s health training concentrates on relieving stress on the body and mind. In the 21st century, Tai chi classes that purely emphasize health are popular in hospitals, clinics, community centers and senior centers. Tai chi’s low-stress training method for seniors has become better known.[37]

A Chinese woman performs Yang-style tàijíquán.

Clinical studies exploring Tai chi’s effect on specific diseases and health conditions exist, though there are not sufficient studies with consistent approaches to generate a comprehensive conclusion.[38]

Tai chi has been promoted for treating various ailments, and is supported by the Parkinson’s Foundation and Diabetes Australia, among others. However, medical evidence of effectiveness is lacking and research has been undertaken to address this.[39][40] A 2017 systematic review found that it decreased falls in older people.[41]

Sport and self-defense[edit]

As a martial art, tai chi emphasizes defense over attack and replies to hard with soft. The ability to use tai chi as a form of combat is the test of a student’s understanding of the art. This is typically demonstrated via competition with others.

Practitioners test their skills against students from other schools and martial arts styles in tuishou («pushing hands») and sanshou competition.

Wushu[edit]

Wushu is primarily for show. Forms taught for wushu are designed to earn points in competition and are mostly unconcerned with either health or self-defense.

Benefits[edit]

A 2011 comprehensive overview of systematic reviews of tai chi recommended tai chi to older people for its physical and psychological benefits. No conclusive evidence showed benefit for any of the conditions researched, including Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, cancer and arthritis.[39]

A 2015 systematic review found that tai chi could be performed by those with chronic medical conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, and osteoarthritis without negative effects, and found favorable effects on functional exercise capacity .[42]

In 2015 the Australian Government’s Department of Health published the results of a review of alternative therapies that sought to identify any that were suitable for coverage by health insurance. T’ai-chi was one of 17 therapies evaluated. The study concluded that low-quality evidence suggests that tai chi may have some beneficial health effects when compared to control in a limited number of populations for a limited number of outcomes.[40]

In 2022, the U.S.A agency the National Institutes of Health published an analysis of various health claims, studies and findings. They concluded the evidence was of low quality, but that it appears to have a small positive effect on quality of life.[43]

In media[edit]

- Tai chi was the inspiration for waterbending in the Nickelodeon animated series Avatar: The Legend of Aang and its sequel The Legend of Korra.

- The Marvel Cinematic Universe movie Shang Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings features tai chi being used by the title character, his mother, his aunt, and his sister.

- Kung Fu Hustle features tai chi being used by the Landlord of Pigsty Alley.

See also[edit]

- Martial arts

- Self-healing

- Wushu

- Yangsheng (Daoism)

References[edit]

- ^ Defoort, Carine (2001). «Is There Such a Thing as Chinese Philosophy Arguments of an Implicit Debate». Philosophy East and West. 51 (3): 404. doi:10.1353/pew.2001.0039. S2CID 54844585.

Just as Shadowboxing (taijiquan) is having success in the West

- ^ «Wudang Martial Arts». China Daily. 2010-06-17.

Wudang boxing includes boxing varieties such as Taiji (shadowboxing)

(…) - ^ Bai, Shuping (2009). Taiji Quan (Shadow Boxing), Bilingual English-Chinese. Beijing University Press. ISBN 9787301053911.

- ^ a b Wile, Douglas (1995). Lost T’ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch’ing Dynasty (Chinese Philosophy and Culture). State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2654-8.[page needed]

- ^ Morris, Kelly (1999). «T’ai Chi gently reduces blood pressure in elderly». The Lancet. 353 (9156): 904. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)75012-1. S2CID 54366341.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wile, Douglas. Taijiquan and Daoism: From Religion to Martial Art and Martial Art to Religion. Journal of Asian Martial Arts (Vol. 16, Issue 4).

- ^ Cheng Man-ch’ing (1993). Cheng-Tzu’s Thirteen Treatises on T’ai Chi Ch’uan. North Atlantic Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-938190-45-5.

- ^ Sun Lu Tang (2000). Xing Yi Quan Xue. Unique Publications. p. 3. ISBN 0-86568-185-6.

- ^ Ranne, Nabil. «Internal power in Taijiquan». CTND. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ^ a b c d Wile, Douglas (2007). «Taijiquan and Taoism from Religion to Martial Art and Martial Art to Religion». Journal of Asian Martial Arts. Via Media Publishing. 16 (4). ISSN 1057-8358.

- ^ Wong Kiew Kit (1996). The Complete Book of Tai Chi Chuan: A Comprehensive Guide to the Principles. Element Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85230-792-9.

- ^ a b Wu, Kung-tsao (2006). Wu Family T’ai Chi Ch’uan (吳家太極拳). Chien-ch’uan T’ai-chi Ch’uan Association. ISBN 0-9780499-0-X.[page needed]

- ^ Yang, Jwing-Ming (1998). The Essence of Taiji Qigong, Second Edition : The Internal Foundation of Taijiquan (Martial Arts-Qigong). YMAA Publication Center. ISBN 978-1-886969-63-6.

- ^ YeYoung, Bing. «Introduction to Taichi and Qigong». YeYoung Culture Studies: Sacramento, CA <http://sactaichi.com>. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2012-01-16.

- ^ Lam, Dr. Paul (28 January 2014). «What should I wear to practice Tai Chi?». Tai Chi for Health Institute. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ Fu, Zhongwen (2006). Mastering Yang Style Taijiquan. Louis Swaim. Berkeley, California: Blue Snake Books. ISBN 1-58394-152-5.[page needed]

- ^ Quarta, Cynthia W. (2001). Tai Chi in a Chair (first ed.). Fair Winds Press. ISBN 1-931412-60-X.

- ^ 由《輔行訣臟腑用藥法要》到香港當代新經學. ASIN B082B24CNP.

- ^ «International Wushu Federation». iwuf.org. Archived from the original on 2006-02-09.

- ^ a b c d Wile, Douglas. 2016. ‘Fighting Words: Four New Document Finds Reignite Old Debates in Taijiquan Historiography’, Martial Arts Studies 4, 17-35.

- ^ a b c Henning, Stanley (1994). «Ignorance, Legend and Taijiquan». Journal of the Chen Style Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii. 2 (3). Archived from the original on 2010-01-01. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ^ Chen, Mark (2004). Old frame Chen family Taijiquan. Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books : Distributed to the book trade by Publishers Group West. ISBN 978-1-55643-488-4.

- ^ Wile, Douglas (1995). Lost T’ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch’ing Dynasty (Chinese Philosophy and Culture). State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2654-8.

- ^ Wile, Douglas (1983). Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions. Sweet Ch’i Press. ISBN 978-0-912059-01-3.

- ^ «Origins and Development of Taijiquan». Chinafrominside.com. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ^ «Taijiquan – Brief Analysis of Chen Family Boxing Manuals». Chinafrominside.com. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ^ «Thirteen Postures of Taijiquan». egreenway.com. Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- ^ «Wushu likely to be a «specially-set» sport at Olympics». Chinese Olympic Committee. October 17, 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ^ «Taijiquan». UNESCO Culture Sector. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ Choy, Kam Man (1985). Tai Chi Chuan. San Francisco, California: Memorial Edition 1994.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Logan, Logan (1970). Ting: The Caldron, Chinese Art and Identity in San Francisco. San Francisco, California: Glide Urban Center.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Dunning, Jennifer (July 7, 1996), «Sophia Delza Glassgold, 92, Dancer and Teacher», The New York Times

- ^ Inventory of the Sophia Delza Papers, 1908–1996 (PDF), Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, February 2006

- ^ Wolfe Lowenthal (1991). There Are No Secrets: Professor Cheng Man Ch’ing and His Tai Chi Chuan. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-112-8.

- ^ «Pytt Geddes (obituary)». The Telegraph. 21 March 2006. Archived from the original on 4 December 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Woolidge, Doug (June 1997). «T’AI CHI». The International Magazine of T’ai Chi Ch’uan. Wayfarer Publications. 21 (3). ISSN 0730-1049.

- ^ Yip, Y. L. (Autumn 2002). «Pivot – Qi». The Journal of Traditional Eastern Health and Fitness. Insight Graphics Publishers. 12 (3). ISSN 1056-4004.

- ^ Yang GY, Wang LQ, Ren J, Zhang Y, Li ML, Zhu YT, Luo J, Cheng YJ, Li WY, Wayne PM, Liu JP (2015). «Evidence base of clinical studies on Tai Chi: a bibliometric analysis». PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0120655. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1020655Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120655. PMC 4361587. PMID 25775125.

- ^ a b Lee, M. S.; Ernst, E. (2011). «Systematic reviews of t’ai chi: An overview». British Journal of Sports Medicine. 46 (10): 713–8. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2010.080622. PMID 21586406. S2CID 206878632.

- ^ a b Baggoley C (2015). «Review of the Australian Government Rebate on Natural Therapies for Private Health Insurance» (PDF). Australian Government – Department of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- Lay summary in: Scott Gavura (November 19, 2015). «Australian review finds no benefit to 17 natural therapies». Science-Based Medicine.

- ^ Lomas-Vega, R; Obrero-Gaitán, E; Molina-Ortega, FJ; Del-Pino-Casado, R (September 2017). «Tai Chi for Risk of Falls. A Meta-analysis». Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 65 (9): 2037–2043. doi:10.1111/jgs.15008. PMID 28736853. S2CID 21131912.

- ^ Chen, Yi-Wen; Hunt, Michael A.; Campbell, Kristin L.; Peill, Kortni; Reid, W. Darlene (2015-09-17). «The effect of Tai Chi on four chronic conditions – cancer, osteoarthritis, heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses». British Journal of Sports Medicine. 50 (7): bjsports-2014-094388. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094388. ISSN 1473-0480. PMID 26383108.

- ^ Tai Chi: What You Need To Know by National Institutes of Health, March 2022

Further reading[edit]

Books[edit]

- Gaffney, David; Sim, Davidine Siaw-Voon (2014). The Essence of Taijiquan. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-5006-0923-8.

- Bluestein, Jonathan (2014). Research of Martial Arts. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-4991-2251-0.

- Yang, Yang; Grubisich, Scott A. (2008). Taijiquan: The Art of Nurturing, The Science of Power (2nd ed.). Zhenwu Publication. ISBN 978-0-9740990-1-9.

- Frantzis, Bruce (2007). The Power of Internal Martial Arts and Chi: Combat and Energy Secrets of Ba Gua, Tai Chi and Hsing-I. Blue Snake Books. ISBN 978-1-58394-190-4.

- Davis, Barbara (2004). Taijiquan Classics: An Annotated Translation. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-431-0.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (1986). A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. ISBN 0-415-00228-1.

- Choy, Kam Man (1985). Tai Chi Chuan. San Francisco, California: Memorial Edition 1994.[ISBN missing]

- Agar-Hutton, Robert (2018), The Metamorphosis of Tai Chi: Created to kill; evolved to heal; teaching peace. Ex-L-Ence Publishing. ISBN 978-1-9164944-1-1

- Wile, Douglas (1983). Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions. Sweet Ch’i Press. ISBN 978-0-912059-01-3.

- Bond, Joey (1999). See Man Jump See God Fall: Tai Chi Vs. Technology. International Promotions Promotion Pub. ISBN 978-1-57901-001-0.

Magazines[edit]

- Taijiquan Journal ISSN 1528-6290

- T’ai Chi Magazine ISSN 0730-1049 Wayfarer Publications. Bimonthly.

«Tao Chi» redirects here. For the Chinese landscape painter, calligrapher and poet, see Tao Chi (painter).

The lower dantian in Taijiquan: |

|

Yang Chengfu (c. 1931) in Single Whip posture of Yang-style t’ai chi ch’uan solo form |

|

| Also known as | Tàijí; T’ai chi |

|---|---|

| Focus | Chinese Taoism |

| Hardness |

|

| Country of origin | China |

| Creator | Chen Wangting or Zhang Sanfeng |

| Famous practitioners |

|

| Olympic sport | Demonstration only |

| Tai chi | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 太極拳 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 太极拳 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | «Taiji Boxing» | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Tai chi (traditional Chinese: 太極; simplified Chinese: 太极; pinyin: Tàijí), short for Tai chi ch’üan (太極拳; 太极拳; Tàijíquán), sometimes called «shadowboxing»,[1][2][3] is an internal Chinese martial art practiced for defense training, health benefits and meditation. Tai chi has practitioners worldwide from Asia to the Americas.

Practitioners such as Yang Chengfu and Sun Lutang in the early 20th Century promoted the art for its health benefits.[4] Its global following may be attributed to overall benefit to personal health.[5] Many forms are practiced, both traditional and modern. Most modern styles trace their development to the five traditional schools: Chen, Yang, Wu (Hao), Wu, and Sun. All trace their historical origins to Chen Village.

Conceptual background[edit]

Zhou Dunyi’s Taijitu diagram which illustrates the Taijitu cosmology.

The philosophical and conceptual background to Tai chi relies on Chinese philosophy, particularly Daoist and Confucian thought as well as on the Chinese classics.[6] Early Tai Chi texts include embedded quotations from classic Chinese works like the Yijing, Great Learning, Book of History, Records of the Grand Historian, Zhu Xi, Zhou Dunyi, Mencius and Zhuangzi.[6]

Early Tai Chi sources also ground Tai Chi in the cosmology of Tai Chi ((太极, tàijí, «Supreme Polarity», or «Greatest Ultimate») from which the art gets its name. Tai Chi cosmology appears in both Taoist and Confucian philosophy, where it represents the single source or mother of yin and yang (represented by the taijitu symbol ).[7][6] Tai Chi also draws on Chinese theories of the body, particularly Daoist neidan (internal alchemy) teachings on Qi (vital energy) and on the three dantiens. Zheng Manqing emphasizes the Daoist background of Tai Chi and states that «Taijiquan enables us to reach the stage of undifferentiated pure yang, which is exactly the same as Laozi’s ‘concentrating the qi and developing softness'».[6]

As such, Tai Chi considers itself an «internal» martial art which focuses on developing the qi.[6] In China, Tai Chi is categorized under the Wudang grouping of Chinese martial arts[8]—that is, arts applied with internal power.[9] Although the term ‘Wudang’ suggests these arts originated in the Wudang Mountains, it is used only to distinguish the skills, theories and applications of neijia (internal arts) from those of the Shaolin grouping, or waijia (hard or external) styles.[10]

Tai Chi also adopts the Daoist ideals of softness overcoming hardness, of wu-wei (effortless action), and of yielding into its martial art technique, while also retaining Daoist ideas of spiritual self-cultivation.[6]

Tai Chi’s path is one of developing naturalness by relaxing, attending inward, and slowing mind, body and breath.[6] This allows us to become less tense, to drop our conditioned habits, let go of thoughts, allow qi to flow smoothly, and thus to flow with the Dao. It is thus a kind of moving meditation that allows us to let go of the self (wuwo), and experience no-mind (wuxin) and spontaneity (ziran).[6]

A key aspect of Tai Chi philosophy is to work with the flow of yin (softness) and yang (hardness) elements. When two forces push each other with equal force, neither side moves. Motion cannot occur until one side yields. Therefore, a key principle in Tai Chi is to avoid using force directly against force (hardness against hardness). Lao Tzŭ provided the archetype for this in the Tao Te Ching when he wrote, «The soft and the pliable will defeat the hard and strong.» Conversely, when in possession of leverage, one may want to use hardness to force the opponent to become soft. Traditionally, Tai Chi uses both soft and hard. Yin is said to be the mother of Yang, using soft power to create hard power.

Traditional schools also emphasize that one is expected to show wude («martial virtue/heroism»), to protect the defenseless, and show mercy to one’s opponents.[4]

Practice[edit]

Traditionally, the foundational Tai Chi practice consists of learning and practicing a specific solo forms or routines (taolu).[6] This entails learning a routine sequence of movements that emphasize a straight spine, abdominal breathing and a natural range of motion. Tai chi relies on knowing the appropriate change in response to outside forces, as well as on yielding to and redirecting an attack, rather than meeting it with opposing force.[11] Physical fitness is also seen as an important step towards effective self-defense.

There are also numerous other supporting solo practices such as:[6]

- Sitting meditation: The empty, focus and calm the mind and aid in opening the microcosmic orbit.

- Standing meditation (zhan zhuang) to raise the yang qi

- Qigong to mobilize the qi

- Acupressure massage to develop awareness of qi channels

- Traditional Chinese medicine is taught to advanced students in some traditional schools.[12]

Further training entails learning tuishou (push hands drills), sanshou (striking techniques), free sparring, grappling training, and weapons training.[6]

In the «T’ai-chi classics», writings by tai chi masters, it is noted that the physiological and kinesiological aspects of the body’s movements are characterized by the circular motion and rotation of the pelvis, based on the metaphors of the pelvis as the hub and the arms and feet as the spokes of a wheel. Furthermore, the respiration of breath is coordinated with the physical movements in a state of deep relaxation, rather than muscular tension, in order to guide the practitioners to a state of homeostasis.

Tai Chi Quan is a complete martial art system with a full range of bare-hand movement sets and weapon forms, such as Tai Chi sword and Tai Chi spear, which are based on the dynamic relationship between Yin and Yang. While Tai Chi is typified by its slow movements, many styles (including the three most popular: Yang, Wu, and Chen) have secondary, faster-paced forms. Some traditional schools teach martial applications of the postures of different forms (taolu).

Solo practices[edit]

Taolu (solo «forms») is a choreography that serves as the encyclopedia of a martial art. Tai chi is often characterized by slow movements in Taolu practice, and one of the reasons is to develop body awareness. Accurate, repeated practice of the solo routine is said to retrain posture, encourage circulation throughout students’ bodies, maintain flexibility, and familiarize students with the martial sequences implied by the forms. The traditional styles of tai chi have forms that differ in aesthetics, but share many similarities that reflect their common origin.

Solo forms (empty-hand and weapon) are catalogues of movements that are practised individually in pushing hands and martial application scenarios to prepare students for self-defense training. In most traditional schools, variations of the solo forms can be practised: fast / slow, small-circle / large-circle, square / round (different expressions of leverage through the joints), low-sitting/high-sitting (the degree to which weight-bearing knees stay bent throughout the form).

Breathing exercises; neigong (internal skill) or, more commonly, qigong (life energy cultivation) are practiced to develop qi (life energy) in coordination with physical movement and zhan zhuang (standing like a post) or combinations of the two. These were formerly taught as a separate, complementary training system. In the last 60 years they have become better known to the general public. Qigong involves coordinated movement, breath, and awareness used for health, meditation, and martial arts. While many scholars and practitioners consider tai chi to be a type of qigong,[13][14] the two are commonly seen as separate but closely related practices. Qigong plays an important role in training for tai chi. Many tai chi movements are part of qigong practice. The focus of qigong is typically more on health or meditation than martial applications. Internally the main difference is the flow of qi. In qigong, the flow of qi is held at a gate point for a moment to aid the opening and cleansing of the channels.[clarification needed] In tai chi, the flow of qi is continuous, thus allowing the development of power by the practitioner.

Partnered practice[edit]

Two students receive instruction in tuishou («pushing hands»), one of the core training exercises of t’ai-chi ch’üan.

Tai chi’s martial aspect relies on sensitivity to the opponent’s movements and center of gravity, which dictate appropriate responses. Disrupting the opponent’s center of gravity upon contact is the primary goal of the martial t’ai-chi ch’üan student.[12] The sensitivity needed to capture the center is acquired over thousands of hours of first yin (slow, repetitive, meditative, low-impact) and then later adding yang (realistic, active, fast, high-impact) martial training through taolu (forms), tuishou (pushing hands), and sanshou (sparring). Tai chi trains in three basic ranges: close, medium and long. Pushes and open-hand strikes are more common than punches, and kicks are usually to the legs and lower torso, never higher than the hip, depending on style. The fingers, fists, palms, sides of the hands, wrists, forearms, elbows, shoulders, back, hips, knees, and feet are commonly used to strike. Targets are the eyes, throat, heart, groin, and other acupressure points. Chin na, which are joint traps, locks, and breaks are also used. Most tai chi teachers expect their students to thoroughly learn defensive or neutralizing skills first, and a student must demonstrate proficiency with them before learning offensive skills.

Martial schools focus on how the energy of a strike affects the opponent. A palm strike that looks to have the same movement may be performed in such a way that it has a completely different effect on the opponent’s body. A palm strike could simply push the opponent backward, or instead be focused in such a way as to lift the opponent vertically off the ground, changing center of gravity; or it could project the force of the strike into the opponent’s body with the intent of causing internal damage.

Most development aspects are meant to be covered within the partnered practice of tuishou, and so, sanshou (sparring) is not commonly used as a method of training, although more advanced students sometimes practice by sanshou. Sanshou is more common to tournaments such as wushu tournaments.

Weapon practice[edit]

Tai chi practices involving weapons also exist. Weapons training and fencing applications often employ:

- the jian, a straight double-edged sword, practiced as taijijian;

- the dao, a heavier curved saber, sometimes called a broadsword;

- the tieshan, a folding fan, also called shan and practiced as taijishan;

- the gun, a 2 m long wooden staff and practiced as taijigun;

- the qiang, a 2 m long spear or a 4 m long lance.

More exotic weapons include:

- the large dadao and podao sabres;

- the ji, or halberd;

- the cane;

- the sheng biao, or rope dart;

- the sanjiegun, or three sectional staff;

- the feng huo lun, or wind and fire wheels;

- the lasso;

- the whip, chain whip and steel whip.

Attire and ranking[edit]

Master Yang Jun in demonstration attire that has come to be identified with tai chi

Some martial arts require students to wear a uniform during practice. In general, Tai Chi does not specify a uniform, although teachers often advocate loose, comfortable clothing and flat-soled shoes.[15][16] Modern day practitioners usually wear comfortable, loose T-shirts and trousers made from breathable natural fabrics, that allow for free movement. Despite this, T’ai-chi ch’üan has become synonymous with «t’ai-chi uniforms» or «kung fu uniforms» that usually consist of loose-fitting traditional Chinese styled trousers and a long or short-sleeved shirt, with a Mandarin collar and buttoned with Chinese frog buttons. The long-sleeved variants are referred to as Northern-style uniforms, whilst the short-sleeved, are Southern-style uniforms.

The clothing may be all white, all black, black and white, or any other colour, mostly a single solid colour or a combination of two colours: one colour for the garment and another for the binding. They are normally made from natural fabrics such as cotton or silk. They are usually worn by masters and professional practitioners during demonstrations, tournaments and other public exhibitions.

Tai chi has no standardized ranking system, except the Chinese Wushu Duan wei exam system run by the Chinese wushu association in Beijing. Most schools do not use belt rankings. Some schools present students with belts depicting rank, similar to dans in Japanese martial arts. A simple uniform element of respect and allegiance to one’s teacher and their methods and community, belts also mark hierarchy, skill, and accomplishment. During wushu tournaments, masters and grandmasters often wear «kung fu uniforms» which tend to have no belts. Wearing a belt signifying rank in such a situation would be unusual.

Seated tai chi[edit]

Seated tai chi demonstration

Traditional tai chi was developed for self-defense, but it has evolved to include a graceful form of seated exercise now used for stress reduction and other health conditions. Often described as meditation in motion, seated tai chi promotes serenity through gentle, flowing movements. Seated tai chi exercises is touted by the medical community and researchers. It is based primarily on the Yang short form, and has been adopted by the general public, medical practitioners, tai chi instructors, and the elderly. Seated forms are not a simple redesign of the yang short form. Instead, the practice attempts to preserve the integrity of the form, with its inherent logic and purpose. The synchronization of the upper body with the steps and the breathing developed over hundreds of years, and guided the transition to seated positions. Marked improvements in balance, blood pressure levels, flexibility and muscle strength, peak oxygen intake, and body fat percentages can be achieved.[17]

Etymology[edit]

Tai Chi was known as «大恒» by the Ancient Chinese. The silk version of I Ching recorded this original name. Due to the name taboo of Emperor Wen of Western Han Empire , «大恒» changed to «太極.». Sundial shadow length changes represent traditional Chinese Medicine with four elements theory instead of Confucian politician-based five elements theory.[18] In the beginning, the color white was associated with Yin, while black was associated with Yang. Confucianism uses the reverse.

The term taiji is a Chinese cosmological concept for the flux of yin and yang. ‘Quan’ means technique.

Tàijíquán and T’ai-chi ch’üan are two different transcriptions of three Chinese characters that are the written Chinese name for the art form:

| Characters | Wade–Giles | Pinyin | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| 太極 | t’ai chi | tàijí | the relationship of Yin and Yang |

| 拳 | ch’üan | quán | technique |

The English language offers two spellings, one derived from Wade–Giles and the other from the Pinyin transcription. Most Westerners often shorten this name to t’ai chi (often omitting the aspirate sign—thus becoming «tai chi»). This shortened name is the same as that of the t’ai-chi philosophy. However, the Pinyin romanization is taiji. The chi in the name of the martial art is not the same as ch’i (qi 气 the «life force»). Ch’i is involved in the practice of t’ai-chi ch’üan. Although the word 极 is traditionally written chi in English, the closest pronunciation, using English sounds, to that of Standard Chinese would be jee, with j pronounced as in jump and ee pronounced as in bee. Other words exist with pronunciations in which the ch is pronounced as in champ. Thus, it is important to use the j sound. This potential for confusion suggests preferring the pinyin spelling, taiji. Most Chinese use the Pinyin version.[19]

History[edit]

Early development[edit]

Taijiquan’s formative influences came from practices undertaken in Taoist and Buddhist monasteries, such as Wudang, Shaolin and The Thousand Year Temple in Henan.[20] The early development of Tai Chi proper is connected with Henan’s Thousand Year Temple and a nexus of nearby villages: Chen Village, Tang Village, Wangbao Village, and Zhaobao Town. These villages were closely connected, shared an interest in the martial arts and many went to study at Thousand Year Temple (which was a syncretic temple with elements from the three teachings).[20] New documents from these villages, mostly dating to the 17th century, are some of the earliest sources for the practice of Taijiquan.[20]

Some traditionalists claim that Tai chi is a purely Chinese art that comes from ancient Daoism and Confucianism.[10] These schools believe that Tai chi theory and practice were formulated by Taoist monk Zhang Sanfeng in the 12th century. These stories are often filled with legendary and hagiographical content and lack historical support.[10][20]

Modern historians pointing out that the earliest reference indicating a connection between Zhang Sanfeng and martial arts is actually a 17th-century piece called Epitaph for Wang Zhengnan (1669), composed by Huang Zongxi (1610–1695).[21][6] Aside from this single source, the other claims of connections between Tai chi and Zhang Sanfeng appeared no earlier than the 19th century.[21][6] According to Douglas Wile, «there is no record of a Zhang Sanfeng in the Song Dynasty (960-1279), and there is no mention in the Ming (1368-1644) histories or hagiographies of Zhang Sanfeng of any connection between the immortal and the material arts.»[6]

Another common theory for the origin of Tai Chi is that it was created by Chen Wangting (1580–1660) while living in Chen Village (陳家溝), Henan province.[22] The other four contemporary traditional Taijiquan styles (Yang, Sun, Wu and Wu (Hao)) trace their teachings back to Chen village in the early 1800s.[23][24]

Yang Luchan (1799–1872), the founder of the popular Yang style, trained with the Chen family for 18 years before he started to teach in Beijing, which strongly suggests that his work was heavily influenced by the Chen family art. Martial arts historian Xu Zhen claimed that the Tai chi of Chen Village was influenced by the Taizu changquan style practiced at nearby Shaolin Monastery, while Tang Hao thought it was derived from a treatise by Ming dynasty general Qi Jiguang, Jixiao Xinshu («New Treatise on Military Efficiency»), which discussed several martial arts styles including Taizu changquan.[25][26]

Tai Chi appears to have received the name «Tai Chi» during the mid-19th century.[21] Imperial Court scholar Ong Tong witnessed a demonstration by Yang Luchan before Yang had established his reputation as a teacher. Afterwards Ong wrote: «Hands holding Tai chi shakes the whole world, a chest containing ultimate skill defeats a gathering of heroes.» Before this time the art may have had other names, and appears to have been generically described by outsiders as zhan quan (沾拳, «touch boxing»), Mian Quan («soft boxing») or shisan shi (十三式, «the thirteen techniques»).[27]

Standardization[edit]

Taoist practitioners practising

In 1956 the Chinese government sponsored the Chinese Sports Committee (CSC), which brought together four wushu teachers to truncate the Yang family hand form to 24 postures. This was an attempt to standardize T’ai-chi ch’üan for wushu tournaments as they wanted to create a routine that would be much less difficult to learn than the classical 88 to 108 posture solo hand forms.

Another 1950s form is the «97 movements combined t’ai-chi ch’üan form», which blends Yang, Wu, Sun, Chen, and Fu styles.

In 1976, they developed a slightly longer demonstration form that would not require the traditional forms’ memory, balance, and coordination. This became the «Combined 48 Forms» that were created by three wushu coaches, headed by Men Hui Feng. The combined forms simplified and combined classical forms from the original Chen, Yang, Wu, and Sun styles. Other competitive forms were designed to be completed within a six-minute time limit.

In the late 1980s, CSC standardized more competition forms for the four major styles as well as combined forms. These five sets of forms were created by different teams, and later approved by a committee of wushu coaches in China. These forms were named after their style: the «Chen-style national competition form» is the «56 Forms». The combined forms are «The 42-Form» or simply the «Competition Form».

In the 11th Asian Games of 1990, wushu was included as an item for competition for the first time with the 42-Form representing t’ai-chi ch’üan. The International Wushu Federation (IWUF) applied for wushu to be part of the Olympic games.[28]

Taijiquan was added to the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists in 2020 for China.[29]

Styles[edit]

Chinese origin[edit]

The five major styles of tai chi are named for the Chinese families who originated them:

- Chen style (陳氏) of Chen Wangting (1580–1660)

- Yang style (楊氏) of Yang Luchan (1799–1872)

- Wu Hao style (武氏) of Wu Yuxiang (1812–1880)

- Wu style (吳氏) of Wu Quanyou (1834–1902) and his son Wu Jianquan (1870–1942)

- Sun style (孫氏) of Sun Lutang (1861–1932)

The most popular is Yang, followed by Wu, Chen, Sun and Wu/Hao.[10] The styles share underlying theory, but their training differs.

Dozens of new styles, hybrid styles, and offshoots followed, although the family schools are accepted as standard by the international community. Other important styles are Zhaobao tàijíquán, a close cousin of Chen style, which is recognized by Western practitioners; Fu style, created by Fu Chen Sung, which evolved from Chen, Sun and Yang styles, and incorporates movements from Baguazhang (Pa Kua Chang)[citation needed]; and Cheng Man-ch’ing style which simplifies Yang style.

Most existing styles came from Chen style, which had been passed down as a family secret for generations. The Chen family chronicles record Chen Wangting, of the family’s 9th generation, as the inventor of what is known today as tai chi. Yang Luchan became the first person outside the family to learn tai chi. His success in fighting earned him the nickname Yang Wudi, which means «Abnormally Large», and his fame and efforts in teaching greatly contributed to the subsequent spreading of tai chi knowledge.[citation needed]

The designation internal or neijia martial arts is also used to broadly distinguish what are known as external or waijia styles based on Shaolinquan styles, although that distinction may be disputed by modern schools. In this broad sense, all styles of t’ai chi, as well as related arts such as Baguazhang and Xingyiquan, are, therefore, considered to be «soft» or «internal» martial arts.

United States[edit]

Choy Hok Pang, a disciple of Yang Chengfu, was the first known proponent of tai chi to openly teach in the United States, beginning in 1939. His son and student Choy Kam Man emigrated to San Francisco from Hong Kong in 1949 to teach t’ai-chi ch’üan in Chinatown. Choy Kam Man taught until he died in 1994.[30][31]

Sophia Delza, a professional dancer and student of Ma Yueliang, performed the first known public demonstration of tai chi in the United States at the New York City Museum of Modern Art in 1954. She wrote the first English language book on t’ai-chi, «T’ai-chi ch’üan: Body and Mind in Harmony», in 1961. She taught regular classes at Carnegie Hall, the Actors Studio, and the United Nations.[32][33]

Zheng Manqing/Cheng Man-ch’ing, who opened his school Shr Jung t’ai-chi after he moved to New York from Taiwan in 1964. Unlike the older generation of practitioners, Zheng was cultured and educated in American ways,[clarification needed] and thus was able to transcribe Yang’s dictation into a written manuscript that became the de facto manual for Yang style. Zheng felt Yang’s traditional 108-movement form was unnecessarily long and repetitive, which makes it difficult to learn.[citation needed] He thus created a shortened 37-movement version that he taught in his schools. Zheng’s form became the dominant form in the eastern United States until other teachers immigrated in larger numbers in the 1990s. He taught until his death in 1975.[34]

United Kingdom[edit]

Norwegian Pytt Geddes was the first European to teach tai chi in Britain, holding classes at The Place in London in the early 1960s. She had first encountered tai chi in Shanghai in 1948, and studied with Choy Hok Pang and his son Choy Kam Man (who both also taught in the United States) while living in Hong Kong in the late 1950s.[35]

Lineage[edit]

Note:

- This lineage tree is not comprehensive, but depicts those considered the «gate-keepers» and most recognised individuals in each generation of the respective styles.

- Although many styles were passed down to respective descendants of the same family, the lineage focused on is that of the martial art and its main styles, not necessarily that of the families.

- Each (coloured) style depicted below has a lineage tree on its respective article page that is focused on that specific style, showing a greater insight into the highly significant individuals in its lineage.

- Names denoted by an asterisk are legendary or semi-legendary figures in the lineage; while their involvement in the lineage is accepted by most of the major schools, it is not independently verifiable from known historical records.

- v

- t

- e

Modern forms[edit]

The Cheng Man-ch’ing (Zheng Manqing) and Chinese Sports Commission short forms are derived from Yang family forms, but neither is recognized as Yang family tai chi by standard-bearing Yang family teachers. The Chen, Yang, and Wu families promote their own shortened demonstration forms for competitive purposes.

| (杨澄甫) Yang Chengfu 1883–1936 3rd gen. Yang Yang Big Frame |

||||||||

| (郑曼青) Zheng Manqing 1902–1975 4th gen. Yang Short (37) Form |

Chinese Sports Commission 1956 Beijing (24) Form |

|||||||

| 1989 42 Competition Form (Wushu competition form combined from Chen, Yang, Wu & Sun styles) |

||||||||

Purposes[edit]

The primary purposes of tai chi are health, sport/self-defense and aesthetics.

Practitioners mostly interested in tai chi’s health benefits diverged from those who emphasize self-defense, and also those who attracted by its aesthetic appeal (wushu).

More traditional practitioners hold that the two aspects of health and martial arts make up the art’s yin and yang. The «family» schools present their teachings in a martial art context, whatever the intention of their students.[36]

Health[edit]

Tai chi’s health training concentrates on relieving stress on the body and mind. In the 21st century, Tai chi classes that purely emphasize health are popular in hospitals, clinics, community centers and senior centers. Tai chi’s low-stress training method for seniors has become better known.[37]

A Chinese woman performs Yang-style tàijíquán.

Clinical studies exploring Tai chi’s effect on specific diseases and health conditions exist, though there are not sufficient studies with consistent approaches to generate a comprehensive conclusion.[38]

Tai chi has been promoted for treating various ailments, and is supported by the Parkinson’s Foundation and Diabetes Australia, among others. However, medical evidence of effectiveness is lacking and research has been undertaken to address this.[39][40] A 2017 systematic review found that it decreased falls in older people.[41]

Sport and self-defense[edit]

As a martial art, tai chi emphasizes defense over attack and replies to hard with soft. The ability to use tai chi as a form of combat is the test of a student’s understanding of the art. This is typically demonstrated via competition with others.

Practitioners test their skills against students from other schools and martial arts styles in tuishou («pushing hands») and sanshou competition.

Wushu[edit]

Wushu is primarily for show. Forms taught for wushu are designed to earn points in competition and are mostly unconcerned with either health or self-defense.

Benefits[edit]

A 2011 comprehensive overview of systematic reviews of tai chi recommended tai chi to older people for its physical and psychological benefits. No conclusive evidence showed benefit for any of the conditions researched, including Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, cancer and arthritis.[39]

A 2015 systematic review found that tai chi could be performed by those with chronic medical conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart failure, and osteoarthritis without negative effects, and found favorable effects on functional exercise capacity .[42]

In 2015 the Australian Government’s Department of Health published the results of a review of alternative therapies that sought to identify any that were suitable for coverage by health insurance. T’ai-chi was one of 17 therapies evaluated. The study concluded that low-quality evidence suggests that tai chi may have some beneficial health effects when compared to control in a limited number of populations for a limited number of outcomes.[40]

In 2022, the U.S.A agency the National Institutes of Health published an analysis of various health claims, studies and findings. They concluded the evidence was of low quality, but that it appears to have a small positive effect on quality of life.[43]

In media[edit]

- Tai chi was the inspiration for waterbending in the Nickelodeon animated series Avatar: The Legend of Aang and its sequel The Legend of Korra.

- The Marvel Cinematic Universe movie Shang Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings features tai chi being used by the title character, his mother, his aunt, and his sister.

- Kung Fu Hustle features tai chi being used by the Landlord of Pigsty Alley.

See also[edit]

- Martial arts

- Self-healing

- Wushu

- Yangsheng (Daoism)

References[edit]

- ^ Defoort, Carine (2001). «Is There Such a Thing as Chinese Philosophy Arguments of an Implicit Debate». Philosophy East and West. 51 (3): 404. doi:10.1353/pew.2001.0039. S2CID 54844585.

Just as Shadowboxing (taijiquan) is having success in the West

- ^ «Wudang Martial Arts». China Daily. 2010-06-17.

Wudang boxing includes boxing varieties such as Taiji (shadowboxing)

(…) - ^ Bai, Shuping (2009). Taiji Quan (Shadow Boxing), Bilingual English-Chinese. Beijing University Press. ISBN 9787301053911.

- ^ a b Wile, Douglas (1995). Lost T’ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch’ing Dynasty (Chinese Philosophy and Culture). State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2654-8.[page needed]

- ^ Morris, Kelly (1999). «T’ai Chi gently reduces blood pressure in elderly». The Lancet. 353 (9156): 904. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)75012-1. S2CID 54366341.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wile, Douglas. Taijiquan and Daoism: From Religion to Martial Art and Martial Art to Religion. Journal of Asian Martial Arts (Vol. 16, Issue 4).

- ^ Cheng Man-ch’ing (1993). Cheng-Tzu’s Thirteen Treatises on T’ai Chi Ch’uan. North Atlantic Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-938190-45-5.

- ^ Sun Lu Tang (2000). Xing Yi Quan Xue. Unique Publications. p. 3. ISBN 0-86568-185-6.

- ^ Ranne, Nabil. «Internal power in Taijiquan». CTND. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ^ a b c d Wile, Douglas (2007). «Taijiquan and Taoism from Religion to Martial Art and Martial Art to Religion». Journal of Asian Martial Arts. Via Media Publishing. 16 (4). ISSN 1057-8358.

- ^ Wong Kiew Kit (1996). The Complete Book of Tai Chi Chuan: A Comprehensive Guide to the Principles. Element Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-85230-792-9.

- ^ a b Wu, Kung-tsao (2006). Wu Family T’ai Chi Ch’uan (吳家太極拳). Chien-ch’uan T’ai-chi Ch’uan Association. ISBN 0-9780499-0-X.[page needed]

- ^ Yang, Jwing-Ming (1998). The Essence of Taiji Qigong, Second Edition : The Internal Foundation of Taijiquan (Martial Arts-Qigong). YMAA Publication Center. ISBN 978-1-886969-63-6.

- ^ YeYoung, Bing. «Introduction to Taichi and Qigong». YeYoung Culture Studies: Sacramento, CA <http://sactaichi.com>. Archived from the original on 2014-02-01. Retrieved 2012-01-16.

- ^ Lam, Dr. Paul (28 January 2014). «What should I wear to practice Tai Chi?». Tai Chi for Health Institute. Retrieved 2014-12-29.

- ^ Fu, Zhongwen (2006). Mastering Yang Style Taijiquan. Louis Swaim. Berkeley, California: Blue Snake Books. ISBN 1-58394-152-5.[page needed]

- ^ Quarta, Cynthia W. (2001). Tai Chi in a Chair (first ed.). Fair Winds Press. ISBN 1-931412-60-X.

- ^ 由《輔行訣臟腑用藥法要》到香港當代新經學. ASIN B082B24CNP.

- ^ «International Wushu Federation». iwuf.org. Archived from the original on 2006-02-09.

- ^ a b c d Wile, Douglas. 2016. ‘Fighting Words: Four New Document Finds Reignite Old Debates in Taijiquan Historiography’, Martial Arts Studies 4, 17-35.

- ^ a b c Henning, Stanley (1994). «Ignorance, Legend and Taijiquan». Journal of the Chen Style Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii. 2 (3). Archived from the original on 2010-01-01. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ^ Chen, Mark (2004). Old frame Chen family Taijiquan. Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books : Distributed to the book trade by Publishers Group West. ISBN 978-1-55643-488-4.

- ^ Wile, Douglas (1995). Lost T’ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch’ing Dynasty (Chinese Philosophy and Culture). State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2654-8.

- ^ Wile, Douglas (1983). Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions. Sweet Ch’i Press. ISBN 978-0-912059-01-3.

- ^ «Origins and Development of Taijiquan». Chinafrominside.com. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ^ «Taijiquan – Brief Analysis of Chen Family Boxing Manuals». Chinafrominside.com. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

- ^ «Thirteen Postures of Taijiquan». egreenway.com. Retrieved 2019-09-16.

- ^ «Wushu likely to be a «specially-set» sport at Olympics». Chinese Olympic Committee. October 17, 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ^ «Taijiquan». UNESCO Culture Sector. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- ^ Choy, Kam Man (1985). Tai Chi Chuan. San Francisco, California: Memorial Edition 1994.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Logan, Logan (1970). Ting: The Caldron, Chinese Art and Identity in San Francisco. San Francisco, California: Glide Urban Center.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Dunning, Jennifer (July 7, 1996), «Sophia Delza Glassgold, 92, Dancer and Teacher», The New York Times

- ^ Inventory of the Sophia Delza Papers, 1908–1996 (PDF), Jerome Robbins Dance Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, February 2006

- ^ Wolfe Lowenthal (1991). There Are No Secrets: Professor Cheng Man Ch’ing and His Tai Chi Chuan. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-112-8.

- ^ «Pytt Geddes (obituary)». The Telegraph. 21 March 2006. Archived from the original on 4 December 2007. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

- ^ Woolidge, Doug (June 1997). «T’AI CHI». The International Magazine of T’ai Chi Ch’uan. Wayfarer Publications. 21 (3). ISSN 0730-1049.

- ^ Yip, Y. L. (Autumn 2002). «Pivot – Qi». The Journal of Traditional Eastern Health and Fitness. Insight Graphics Publishers. 12 (3). ISSN 1056-4004.

- ^ Yang GY, Wang LQ, Ren J, Zhang Y, Li ML, Zhu YT, Luo J, Cheng YJ, Li WY, Wayne PM, Liu JP (2015). «Evidence base of clinical studies on Tai Chi: a bibliometric analysis». PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0120655. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1020655Y. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0120655. PMC 4361587. PMID 25775125.

- ^ a b Lee, M. S.; Ernst, E. (2011). «Systematic reviews of t’ai chi: An overview». British Journal of Sports Medicine. 46 (10): 713–8. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2010.080622. PMID 21586406. S2CID 206878632.

- ^ a b Baggoley C (2015). «Review of the Australian Government Rebate on Natural Therapies for Private Health Insurance» (PDF). Australian Government – Department of Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- Lay summary in: Scott Gavura (November 19, 2015). «Australian review finds no benefit to 17 natural therapies». Science-Based Medicine.

- ^ Lomas-Vega, R; Obrero-Gaitán, E; Molina-Ortega, FJ; Del-Pino-Casado, R (September 2017). «Tai Chi for Risk of Falls. A Meta-analysis». Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 65 (9): 2037–2043. doi:10.1111/jgs.15008. PMID 28736853. S2CID 21131912.

- ^ Chen, Yi-Wen; Hunt, Michael A.; Campbell, Kristin L.; Peill, Kortni; Reid, W. Darlene (2015-09-17). «The effect of Tai Chi on four chronic conditions – cancer, osteoarthritis, heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analyses». British Journal of Sports Medicine. 50 (7): bjsports-2014-094388. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094388. ISSN 1473-0480. PMID 26383108.

- ^ Tai Chi: What You Need To Know by National Institutes of Health, March 2022

Further reading[edit]

Books[edit]

- Gaffney, David; Sim, Davidine Siaw-Voon (2014). The Essence of Taijiquan. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-5006-0923-8.

- Bluestein, Jonathan (2014). Research of Martial Arts. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1-4991-2251-0.

- Yang, Yang; Grubisich, Scott A. (2008). Taijiquan: The Art of Nurturing, The Science of Power (2nd ed.). Zhenwu Publication. ISBN 978-0-9740990-1-9.

- Frantzis, Bruce (2007). The Power of Internal Martial Arts and Chi: Combat and Energy Secrets of Ba Gua, Tai Chi and Hsing-I. Blue Snake Books. ISBN 978-1-58394-190-4.

- Davis, Barbara (2004). Taijiquan Classics: An Annotated Translation. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-431-0.

- Eberhard, Wolfram (1986). A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. ISBN 0-415-00228-1.

- Choy, Kam Man (1985). Tai Chi Chuan. San Francisco, California: Memorial Edition 1994.[ISBN missing]

- Agar-Hutton, Robert (2018), The Metamorphosis of Tai Chi: Created to kill; evolved to heal; teaching peace. Ex-L-Ence Publishing. ISBN 978-1-9164944-1-1

- Wile, Douglas (1983). Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions. Sweet Ch’i Press. ISBN 978-0-912059-01-3.