A taekwondo contest at the 2016 Summer Olympics |

|

| Also known as | TKD, Tae Kwon Do, Tae Kwon-Do, Taekwon-Do, Tae-Kwon-Do |

|---|---|

| Focus | Striking, kicking |

| Country of origin | Korea |

| Creator | No single creator; a collaborative effort by representatives from the original nine Kwans, initially supervised by Choi Hong-hi.[1] |

| Famous practitioners | (see notable practitioners) |

| Parenthood | Mainly Taekkyon and Karate,[a] and slight influence of Chinese martial arts[2] |

| Olympic sport | Since 2000 (World Taekwondo) |

| Highest governing body | World Taekwondo (South Korea) |

|---|---|

| First played | Korea, 1940s |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Full-contact (WT), Light and medium-contact (ITF, ITC, ATKDA, GBTF, GTF, ATA, TI,TCUK, TAGB) |

| Mixed-sex | Yes |

| Type | Combat sport |

| Equipment | Hogu, Headgear, |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide |

| Olympic | Since 2000 |

| Paralympic | Since 2020 |

| World Games | 1981–1993 |

| Taekwondo | |

| Hangul |

태권도 |

|---|---|

| Hanja |

跆拳道 |

| Revised Romanization | taegwondo |

| McCune–Reischauer | t’aekwŏndo |

| IPA | [t̪ʰɛ.k͈wʌ̹n.d̪o] ( |

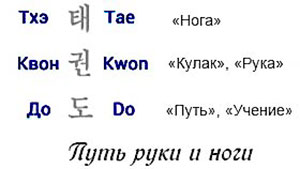

Taekwondo, Tae Kwon Do or Taekwon-Do (;[3][4][5] Korean: 태권도/跆拳道 [t̪ʰɛ.k͈wʌ̹n.d̪o] (listen)) is a Korean form of martial arts involving punching and kicking techniques, with emphasis on head-height kicks, spinning jump kicks, and fast kicking techniques. The literal translation for tae kwon do is «kicking», «punching», and «the art or way of».[6] They are a kind of martial arts in which one attacks or defends with hands and feet anytime or anywhere, with occasional use of weapons. The physical training undertaken in Taekwondo is purposeful and fosters strength of mind through mental armament.[7]

Taekwondo practitioners wear a uniform, known as a dobok. It is a combat sport and was developed during the 1940s and 1950s by Korean martial artists with experience in martial arts such as karate, Chinese martial arts, and indigenous Korean martial arts traditions such as Taekkyon, Subak, and Gwonbeop.[8][9]

The oldest governing body for Taekwondo is the Korea Taekwondo Association (KTA), formed in 1959 through a collaborative effort by representatives from the nine original kwans, or martial arts schools, in Korea. The main international organisational bodies for Taekwondo today are the International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF), founded by Choi Hong-hi in 1966, and the partnership of the Kukkiwon and World Taekwondo (WT, formerly World Taekwondo Federation or WTF), founded in 1972 and 1973 respectively by the Korea Taekwondo Association.[10] Gyeorugi ([kjʌɾuɡi]), a type of full-contact sparring, has been an Olympic event since 2000. In 2018, the South Korean government officially designated Taekwondo as Korea’s national martial art.[11]

The governing body for Taekwondo in the Olympics and Paralympics is World Taekwondo.

History[edit]

Beginning in 1945, shortly after the end of World War II and Japanese Occupation, new martial arts schools called kwans opened in Seoul. These schools were established by Korean martial artists with backgrounds in Japanese[12] and Chinese martial arts. At the time, indigenous disciplines (such as Taekkyeon) were being forgotten, due to years of decline and repression by the Japanese colonial government. The umbrella term traditional Taekwondo typically refers to the martial arts practiced by the kwans during the 1940s and 1950s, though in reality the term «Taekwondo» had not yet been coined at that time, and indeed each kwan (school) was practicing its own unique style of the Korean art.

In 1952, South Korean president Syngman Rhee witnessed a martial arts demonstration by ROK Army officers Choi Hong-hi and Nam Tae-hi from the 29th Infantry Division. He misrecognized the technique on display as Taekkyeon,[13][14][15] and urged martial arts to be introduced to the army under a single system. Beginning in 1955 the leaders of the kwans began discussing in earnest the possibility of creating a unified Korean martial art. Until then, Tang Soo Do was the term used to for Korean Karate, using the Korean hanja pronunciation of the Japanese kanji (唐手道). The name Tae Soo Do (跆手道) was also used to describe a unified style Korean martial arts.[citation needed] This name consists of the hanja 跆 tae «to stomp, trample», 手 su «hand» and 道 do «way, discipline».

Choi Hong-hi advocated the use of the name Tae Kwon Do, replacing su «hand» with 拳 kwon (Revised Romanization: gwon; McCune–Reischauer: kkwŏn) «fist», the term also used for «martial arts» in Chinese (pinyin quán).[16] The name was also the closest to the pronunciation of Taekkyeon,[17] in accordance with the views of the president.[13][18] The new name was initially slow to catch on among the leaders of the kwans. During this time Taekwondo was also adopted for use by the South Korean military, which increased its popularity among civilian martial arts schools.[10][13]

In 1959 the Korea Taekwondo Association or KTA (then-Korea Tang Soo Do Association) was established to facilitate the unification of Korean martial arts. General Choi, of the Oh Do Kwan, wanted all the other member kwans of the KTA to adopt his own Chan Hon-style of Taekwondo, as a unified style. This was, however, met with resistance as the other kwans instead wanted a unified style to be created based on inputs from all the kwans, to serve as a way to bring on the heritage and characteristics of all of the styles, not just the style of a single kwan.[10] As a response to this, along with political disagreements about teaching Taekwondo in North Korea and unifying the whole Korean Peninsula, Choi broke with the (South Korea) KTA in 1966, in order to establish the International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF)— a separate governing body devoted to institutionalizing his Chan Hon-style of Taekwondo in Canada.[10][13]

Initially, the South Korean president, having close ties to General Choi, gave General Choi’s ITF limited support.[10] However, the South Korean government wished to avoid North Korean influence on the martial art. Conversely, ITF president Choi Hong-hi sought support for his Chan Hon-style of Taekwondo from all quarters, including North Korea. In response, in 1972 South Korea withdrew its support for the ITF. The ITF continued to function as an independent federation, then headquartered in Toronto, Ontario, Canada; Choi continued to develop the ITF-style, notably with the 1983 publication of his Encyclopedia of Taekwon-Do. After Choi’s retirement, the ITF split in 2001 and then again in 2002 to create three separate ITF federations each of which continues to operate today under the same name.[10]

In 1972 the KTA and the South Korean government’s Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism established the Kukkiwon as the new national academy for Taekwondo. Kukkiwon now serves many of the functions previously served by the KTA, in terms of defining a government-sponsored unified style of Taekwondo. In 1973 the KTA and Kukkiwon supported the establishment of the World Taekwondo Federation (WTF, renamed to World Taekwondo in 2017 due to confusion with the initialism[19]) to promote the sportive side of Kukki-Taekwondo. WT competitions employ Kukkiwon-style Taekwondo.[10][20] For this reason, Kukkiwon-style Taekwondo is often referred to as WT-style Taekwondo, sport-style Taekwondo, or Olympic-style Taekwondo, though in reality the style is defined by the Kukkiwon, not the WT.

Since 2021, Taekwondo has been one of three Asian martial arts (the others being judo and karate), and one of six total (the others being the previously mentioned, Greco-Roman wrestling, freestyle wrestling, and boxing) included in the Olympic Games. It started as a demonstration event at the 1988 games in Seoul, a year after becoming a medal event at the Pan Am Games, and became an official medal event at the 2000 games in Sydney. In 2010, Taekwondo was accepted as a Commonwealth Games sport.[21]

Features[edit]

Flying twin foot side kick

A jumping reverse hook kick

Taekwondo is characterized by its emphasis on head-height kicks, jumping and spinning kicks, and fast kicking techniques. In fact, World Taekwondo sparring competitions award additional points for strikes that incorporate spinning kicks, kicks to the head, or both.[22] To facilitate fast, turning kicks, Taekwondo generally adopts stances that are narrower and taller than the broader, wide stances used by martial arts such as karate. The tradeoff of decreased stability is believed to be worth the commensurate increase in agility, particularly in Kukkiwon-style Taekwondo.

Theory of power[edit]

The emphasis on speed and agility is a defining characteristic of Taekwondo and has its origins in analyses undertaken by Choi Hong-hi. The results of that analysis are known by ITF practitioners as Choi’s Theory of Power. Choi based his understanding of power on biomechanics and Newtonian physics as well as Chinese martial arts. For example, Choi observed that the kinetic energy of a strike increases quadratically with the speed of the strike, but increases only linearly with the mass of the striking object. In other words, speed is more important than size in terms of generating power. This principle was incorporated into the early design of Taekwondo and is still used.[13][23]

Choi also advocated a relax/strike principle for Taekwondo; in other words, between blocks, kicks, and strikes the practitioner should relax the body, then tense the muscles only while performing the technique. It is believed that the relax/strike principle increases the power of the technique, by conserving the body’s energy. He expanded on this principle with his advocacy of the sine wave technique. This involves raising one’s centre of gravity between techniques, then lowering it as the technique is performed, producing the up-and-down movement from which the term «sine wave» is derived.[23] The sine wave is generally practiced, however, only in schools that follow ITF-style Taekwondo. Kukkiwon-style Taekwondo, for example, does not employ the sine wave and advocates a more uniform height during movements, drawing power mainly from the rotation of the hip.

The components of the Theory of Power include:[24]

- Reaction Force: the principle that as the striking limb is brought forward, other parts of the body should be brought backwards in order to provide more power to the striking limb. As an example, if the right leg is brought forward in a roundhouse kick, the right arm is brought backwards to provide the reaction force.

- Concentration: the principle of bringing as many muscles as possible to bear on a strike, concentrating the area of impact into as small an area as possible.

- Equilibrium: maintaining a correct centre-of-balance throughout a technique.

- Breath Control: the idea that during a strike one should exhale, with the exhalation concluding at the moment of impact.

- Mass: the principle of bringing as much of the body to bear on a strike as possible; again using the turning kick as an example, the idea would be to rotate the hip as well as the leg during the kick in order to take advantage of the hip’s additional mass in terms of providing power to the kick.

- Speed: as previously noted, the speed of execution of a technique in Taekwondo is deemed to be even more important than mass in terms of providing power.

Typical curriculum[edit]

A young red/black-belt performs Koryo

While organizations such as ITF or Kukkiwon define the general style of Taekwondo, individual clubs and schools tend to tailor their Taekwondo practices. Although each Taekwondo club or school is different, a student typically takes part in most or all of the following:

[25]

- Forms (pumsae / poomsae 품새, hyeong / hyung 형/型 or teul / tul 틀): these serve the same function as kata in the study of karate

- Sparring (gyeorugi 겨루기 or matseogi 맞서기): sparring includes variations such as freestyle sparring (in which competitors spar without interruption for several minutes); seven-, three-, two-, and one-step sparring (in which students practice pre-arranged sparring combinations); and point sparring (in which sparring is interrupted and then resumed after each point is scored)

- Breaking (gyeokpa 격파/擊破 or weerok): the breaking of boards is used for testing, training, and martial arts demonstrations. Demonstrations often also incorporate bricks, tiles, and blocks of ice or other materials. These techniques can be separated into three types:

- Power breaking – using straightforward techniques to break as many boards as possible

- Speed breaking – boards are held loosely by one edge, putting special focus on the speed required to perform the break

- Special techniques – breaking fewer boards but by using jumping or flying techniques to attain greater height, distance, or to clear obstacles

- Self-defense techniques (hosinsul 호신술/護身術)

- Learning the fundamental techniques of Taekwondo; these generally include kicks, blocks, punches, and strikes, with somewhat less emphasis on grappling and holds

- Throwing and/or falling techniques (deonjigi 던지기 or tteoreojigi 떨어지기)

- Both anaerobic and aerobic workout, including stretching

- Relaxation and meditation exercises, as well as breathing control

- A focus on mental and ethical discipline, etiquette, justice, respect, and self-confidence

- Examinations to progress to the next rank

- Development of personal success and leadership skills

Though weapons training is not a formal part of most Taekwondo federation curricula, individual schools will often incorporate additional training with weapons such as staffs, knives, and sticks.

Equipment and facilities[edit]

A Taekwondo practitioner typically wears a uniform (dobok 도복/道服), often white but sometimes black (or other colors), with a belt tied around the waist. White uniforms are considered the traditional color and are usually encouraged for use at formal ceremonies such as belt tests and promotions. Colored uniforms are often reserved for special teams (such as demonstration teams or leadership teams) or higher-level instructors. There are at least three major styles of dobok, with the most obvious differences being in the style of jacket:

- The cross-over front jacket (usually seen in ITF style), in which the opening of the jacket is vertical.

- The cross-over Y-neck jacket (usually seen in the Kukkiwon/WT style, especially for poomsae competitions), in which the opening of the jacket crosses the torso diagonally.

- The pull-over V-neck jacket (usually seen in Kukkiwon/WT style, especially for sparring competitions).

White uniforms in the Kukkiwon/WT tradition will typically be white throughout the jacket (black trim along the collars only for dan grades), while ITF-style uniforms are usually trimmed with a black border along the collar and bottom of the jacket (for dan grades). The belt color and any insignia thereon indicate the student’s rank. Different clubs and schools use different color schemes for belts. In general, the darker the color, the higher the rank. Taekwondo is traditionally performed in bare feet, although martial arts training shoes may sometimes be worn.

When sparring, padded equipment is usually worn. In the ITF tradition, typically only the hands and feet are padded. For this reason, ITF sparring often employs only light-contact sparring. In the Kukkiwon/WT tradition, full-contact sparring is facilitated by the employment of more extensive equipment: padded helmets called homyun are always worn, as are padded torso protectors called hogu; feet, shins, groins, hands, and forearms protectors are also worn.

The school or place where instruction is given is called a dojang (도장, 道場). Specifically, dojang refers to the area within the school in which martial arts instruction takes place; the word dojang is sometimes translated as gymnasium. In common usage, the term dojang is often used to refer to the school as a whole. Modern dojangs often incorporate padded flooring, often incorporating red-and-blue patterns in the flooring to reflect the colors of the taegeuk symbol. Some dojangs have wooden flooring instead. The dojang is usually decorated with items such as flags, banners, belts, instructional materials, and traditional Korean calligraphy.

Styles and organizations[edit]

A «family tree» illustrating how the five original kwans gave rise to multiple styles of Taekwondo.

There are a number of major Taekwondo styles as well as a few niche styles. Most styles are associated with a governing body or federation that defines the style.[26] The major technical differences among Taekwondo styles and organizations generally revolve around:

- the patterns practiced by each style (called hyeong 형, pumsae 품새, or tul 틀, depending on the style); these are sets of prescribed formal sequences of movements that demonstrate mastery of posture, positioning, and technique

- differences in the sparring rules for competition.

- martial arts philosophy.

1946: Traditional Taekwondo[edit]

The term traditional Taekwondo typically refers to martial arts practised in Korea during the 1940s and 1950s by the nine original kwans, or martial arts schools, after the conclusion of the Japanese occupation of Korea at the end of World War II. The term Taekwondo had not yet been coined, and in reality, each of the nine original kwans practised its own style of martial art. The term traditional Taekwondo serves mostly as an umbrella term for these various styles, as they themselves used various other names such as Tang Soo Do (Chinese Hand Way),[b] Kong Soo Do (Empty Hand Way)[c] and Tae Soo Do (Foot Hand Way).[d] Traditional Taekwondo is still practised today but generally under other names, such as Tang Soo Do and Soo Bahk Do.[10][13] In 1959, the name Taekwondo was agreed upon by the nine original kwans as a common term for their martial arts. As part of the unification process, The Korea Taekwondo Association (KTA) was formed through a collaborative effort by representatives from all the kwans, and the work began on a common curriculum, which eventually resulted in the Kukkiwon and the Kukki Style of Taekwondo. The original kwans that formed KTA continues to exist today, but as independent fraternal membership organizations that support the World Taekwondo and Kukkiwon. The kwans also function as a channel for the issuing of Kukkiwon dan and poom certification (black belt ranks) for their members. The official curriculum of those kwans that joined the unification is that of the Kukkiwon, with the notable exception of half the Oh Do Kwan which joined the ITF instead and therefore uses the Chan Hon curriculum.

1966: ITF/Chang Hon-style Taekwondo[edit]

International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF)-style Taekwondo, more accurately known as Chang Hon-style Taekwondo, is defined by Choi Hong-hi’s Encyclopedia of Taekwon-Do published in 1983.[23]

In 1990, the Global Taekwondo Federation (GTF) split from the ITF due to the political controversies surrounding the ITF; the GTF continues to practice ITF-style Taekwondo, however, with additional elements incorporated into the style. Likewise, the ITF itself split in 2001 and again in 2002 into three separate federations, headquartered in Austria, the United Kingdom, and Spain respectively.[27][28][29]

The GTF and all three ITFs practice Choi’s ITF-style Taekwondo. In ITF-style Taekwondo, the word used for «forms» is tul; the specific set of tul used by the ITF is called Chang Hon. Choi defined 24 Chang Hon tul. The names and symbolism of the Chang Hon tul refer to elements of Korean history, culture and religious philosophy. The GTF-variant of ITF practices an additional six tul.

Within the ITF Taekwondo tradition there are two sub-styles:

- The style of Taekwondo practised by the ITF before its 1973 split with the KTA is sometimes called by ITF practitioners «traditional Taekwondo», though a more accurate term would be traditional ITF Taekwondo.

- After the 1973 split, Choi Hong-hi continued to develop and refine the style, ultimately publishing his work in his 1983 Encyclopedia of Taekwondo. Among the refinements incorporated into this new sub-style is the «sine wave»; one of Choi Hong-hi’s later principles of Taekwondo is that the body’s centre of gravity should be raised-and-lowered throughout a movement.

Some ITF schools adopt the sine wave style, while others do not. Essentially all ITF schools do, however, use the patterns (tul) defined in the Encyclopedia, with some exceptions related to the forms Juche and Ko-Dang.

1969: ATA/Songahm-style Taekwondo[edit]

In 1969, Haeng Ung Lee, a former Taekwondo instructor in the South Korean military, relocated to Omaha, Nebraska and established a chain of martial arts schools in the United States under the banner of the American Taekwondo Association (ATA). Like Jhoon Rhee Taekwondo, ATA Taekwondo has its roots in traditional Taekwondo. The style of Taekwondo practised by the ATA is called Songahm Taekwondo. The ATA went on to become one of the largest chains of Taekwondo schools in the United States.[30]

The ATA established international spin-offs called the Songahm Taekwondo Federation (STF) and the World Traditional Taekwondo Union (WTTU) to promote the practice of Songahm Taekwondo internationally. In 2015, all the spin-offs were reunited under the umbrella of ATA International.

1970s: Jhoon Rhee-style Taekwondo[edit]

In 1962 Jhoon Rhee, upon graduating from college in Texas, relocated to and established a chain of martial arts schools in the Washington, D.C. area that practiced traditional Taekwondo.[e] In the 1970s, at the urging of Choi Hong-hi, Rhee adopted ITF-style Taekwondo within his chain of schools, but like the GTF later departed from the ITF due to the political controversies surrounding Choi and the ITF. Rhee went on to develop his own style of Taekwondo called Jhoon Rhee-style Taekwondo, incorporating elements of both traditional and ITF-style Taekwondo as well as original elements.[31] Jhoon Rhee-style Taekwondo is still practiced primarily in the United States and eastern Europe.

1972: Kukki-style / WT-Taekwondo[edit]

Relative popularity of Kukkiwon-style Taekwondo around the world

In 1972 the Korea Taekwondo Association (KTA) Central Dojang opened in Seoul; in 1973 the name was changed to Kukkiwon. Under the sponsorship of the South Korean government’s Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism the Kukkiwon became the new national academy for Taekwondo, thereby establishing a new «unified» style of Taekwondo.[20] In 1973 the KTA established the World Taekwondo Federation (WTF, now called World Taekwondo, WT) to promote the sportive side of Kukki-Taekwondo. The International Olympic Committee recognized the WT and Taekwondo sparring in 1980. For this reason, the Kukkiwon-defined style of Taekwondo is sometimes referred to as Sport-style Taekwondo, Olympic-style Taekwondo, or WT-style Taekwondo, but the style itself is defined by the Kukkiwon, not by the WT, and the WT competition ruleset itself only allows the use of a very small number of the total number of techniques included in the style.[32] Therefore, the correct term for the South Korean government sponsored style of Taekwondo associated with the Kukkiwon, is Kukki Taekwondo, meaning «national Taekwondo» in Korean.

The color belts range from white to junior black belt (half black, half red) or plain red.[33] The order and colours used may vary between schools, but a common[according to whom?] order is white, yellow, green, blue, red, black[citation needed]. However, other variations with a higher number of colours is also commonly seen. A usual practice[according to whom?], when employing only four coloured belts, is to stay at each belt color for the duration of two gup ranks, making a total of eight gup ranks between white belt and 1st. dan black belt. In order to make a visual difference between the first and second gup rank of given belt color, a stripe in the same color as the next belt color is added to the second gup rank in some schools.

In Kukki-style Taekwondo, the word used for «forms» is poomsae. In 1967 the KTA established a new set of forms called the Palgwae poomsae, named after the eight trigrams of the I Ching. In 1971 however (after additional kwans had joined the KTA), the KTA and Kukkiwon adopted a new set of color-belt forms instead, called the Taegeuk poomsae. Black belt forms are called yudanja poomsae. While ITF-style forms refer to key elements of Korean history, Kukki-style forms refer instead to elements of sino-Korean philosophy such as the I Ching and the taegeuk.

WT-sanctioned tournaments allow any person, regardless of school affiliation or martial arts style, to compete in WT events as long as he or she is a member of the WT Member National Association in his or her nation; this allows essentially anyone to compete in WT-sanctioned competitions.

Other styles and hybrids[edit]

An example of other styles of Taekwondo is Extreme Taekwondo: a complex version of World Taekwondo Federation, which combines elements from all Taekwondo styles, Tricking (martial arts), similarities from other martial arts

There are hybrid martial arts that are not Taekwondo styles but combine techniques of Taekwondo with those of other martial arts. These include:

- Han Moo Do: Scandinavian martial art that combines Taekwondo, hapkido, and hoi jeon moo sool.

- Han Mu Do: Korean martial art that combines Taekwondo and hapkido.

- Teukgong Moosool: Korean martial art that combines elements of Taekwondo, hapkido, judo, kyuk too ki, and Chinese martial arts.

- Yongmudo: developed at Korea’s Yong-In University, combines Taekwondo, hapkido, judo, and ssireum.

Forms (patterns)[edit]

A demonstration at Kuopio-halli in Kuopio, Finland

Three Korean terms may be used with reference to Taekwondo forms or patterns. These forms are equivalent to kata in karate.

- Hyeong (sometimes romanized as hyung; hanja: 形, hangeul: 형) is the term usually used in traditional Taekwondo (i.e., 1950s–1960s styles of Korean martial arts).

- Poomsae (sometimes romanized as pumsae or poomse; hanja: 品勢, hangeul: 품새) is the term officially used by Kukkiwon/WT-style and ATA-style Taekwondo.

- Teul (officially romanized as tul; hangeul: 틀) is the term usually used in ITF/Chang Hon-style Taekwondo.

A hyeong is a systematic, prearranged sequence of martial techniques that is performed either with or without the use of a weapon. In dojangs (Taekwondo training gymnasiums) hyeong are used primarily as a form of interval training that is useful in developing mushin, proper kinetics and mental and physical fortitude. Hyeong may resemble combat, but are artistically non-combative and woven together so as to be an effective conditioning tool. One’s aptitude for a particular hyeong may be evaluated in competition. In such competitions, hyeong are evaluated by a panel of judges who base the score on many factors including energy, precision, speed, and control. In Western competitions, there are two general classes of hyeong: creative and standard. Creative hyeong are created by the performer and are generally acrobatic in nature and do not necessarily reflect the kinetic principles intrinsic in any martial system.

Different Taekwondo styles and associations (ATA, ITF, GTF, WT, etc.) use different Taekwondo forms. Even within a single association, different schools in the association may use slightly different variations on the forms or use different names for the same form (especially in older styles of Taekwondo). This is especially true for beginner forms, which tend to be less standardized than mainstream forms.

| ATA Songahm-style[34] | ITF Chang Hon-style[35] | GTF style[36] | WT Kukkiwon-style[37] | Jhoon Rhee style[38] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beginner Exercises (3) | Beginner Exercises (3) | Unofficial Beginner Forms (usually 3–) | Beginner Forms (2) | |

| Four Direction Punch | Four Direction Punch | Kicho Hyeong Il Bu, Kibon Hana or Kibon Il Jang | Kam Sah | |

| Four Direction Block | Four Direction Block | Kicho Hyeong Ee Bu, Kibon Dool or Kibon Ee Jang | Kyu-Yool | |

| Four Direction Thrust | Four Direction Thrust | Kicho Hyeong Sam Bu, Kibon Set or Kibon Sam Jang | ||

| Kibon Net or Kibon Sa Jang | ||||

| Color Belt Forms (9) | Color Belt Forms (9) | Color Belt Forms (11) | Color Belt Forms (Taegeuk,

|

Color Belt Forms (8) |

| Songahm 1 | Chon-Ji | Chon-Ji | Taegeuk Il Jang | Jayoo |

| Songahm 2 | Dan-Gun | Dan-Gun | Taegeuk Ee Jang | Chosang |

| Songahm 3 | Do-San | Do-San | Taegeuk Sam Jang | Hangook |

| Songahm 4 | Jee-Sang | Taegeuk Sa Jang | Jung-Yi | |

| Songahm 5 | Won-Hyo | Won-Hyo | Taegeuk Oh Jang | Pyung-Wa |

| In Wha 1 | Yul-Gok | Yul-Gok | Taegeuk Yook Jang | Meegook |

| In Wha 2 | Dhan-Goon | Taegeuk Chil Jang | Chasin | |

| Choong Jung 1 | Joong-Gun | Joong-Gun | Taegeuk Pal Jang | Might for Right |

| Choong Jung 2 | Toi-Gye | Toi-Gye | ||

| Hwa-Rang | Hwa-Rang | |||

| Choong-Moo | Choong-Moo | |||

| Black Belt Forms (8) | Black Belt Forms (15) | Black Belt Forms (19) | Black Belt Forms (9) | Black Belt Forms |

| Shim Jun | Kwang-Gae | Kwang-Gae | Koryo | Same as ITF |

| Jung Yul | Po-Eun | Po-Eun | Keumgang | |

| Chung San | Gae-Baek | Gae-Baek | Taebaek | |

| Sok Bong | Jee-Goo | Pyongwon | ||

| Chung Hae | Eui-Am | Eui-Am | Sipjin | |

| Jhang Soo | Choong-Jang | Choong-Jang | Jitae | |

| Chul Joon | Juche, or Go-Dang* | Go-Dang | Cheonkwon | |

| Jeong Seung | Jook-Am | Hansoo | ||

| Sam-Il | Sam-Il | Ilyeo | ||

| Yoo-Sin | Yoo-Sin | |||

| Choi-Yong | Choi-Yong | Older Color Belt Forms (Palgwae,

|

||

| Pyong-Hwa | Palgwae Il Jang | |||

| Yon-Gae | Yon-Gae | Palgwae Ee Jang | ||

| Ul-Ji | Ul-Ji | Palgwae Sam Jang | ||

| Moon-Moo | Moon-Moo | Palgwae Sa Jang | ||

| Sun-Duk | Palgwae Oh Jang | |||

| So-San | So-San | Palgwae Yook Jang | ||

| Se-Jong | Se-Jong | Palgwae Chil Jang | ||

| Tong-Il | Tong-Il | Palgwae Pal Jang | ||

| Older Black Belt Forms | Older Black Belt Forms | |||

| * Go-Dang is considered deprecated in most ITF styles | Original Koryo | |||

| U-Nam is an ITF Chang-Hon form that appears only in

the 1959 edition of Choi Hong-hi’s Tae Kwon Do Teaching Manual[39] |

||||

| Candidate Demo Forms (2007, never officially finalized) | ||||

| Hanryu | ||||

| Bikkak | ||||

| Kukkiwon Competition Poomsae (2016) | ||||

| Himchari | ||||

| Yamang | ||||

| Saebyeol | ||||

| Nareusya (called Bigak Sam Jang by WT) | ||||

| Bigak (called Bigak Ee Jang by WT) | ||||

| Eoullim | ||||

| Saeara | ||||

| Hansol | ||||

| Narae | ||||

| Onnuri | ||||

| WT Competition Poomsae (2017) | ||||

| Bigak Il Jang (developed by WT) | ||||

| Bigak Ee Jang (based on Kukkiwon’s Bigak) | ||||

| Bigak Sam Jang (based on Kukkiwon’s Nareusya) |

Ranks, belts, and promotion[edit]

Taekwondo ranks vary from style to style and are not standardized. Typically, these ranks are separated into «junior» and «senior» sections, colloquially referred to as «color belts» and «black belts»:

- The junior section of ranks—the «color belt» ranks—are indicated by the Korean word geup 급 (級) (also Romanized as gup or kup). Practitioners in these ranks generally wear belts ranging in color from white (the lowest rank) to red or brown (higher ranks, depending on the style of Taekwondo). Belt colors may be solid or may include a colored stripe on a solid background. The number of geup ranks varies depending on the style, typically ranging between 8 and 12 geup ranks. The numbering sequence for geup ranks usually begins at the larger number of white belts, and then counts down to «1st geup» as the highest color-belt rank.

- The senior section of ranks—the «black belt» ranks—is typically made up of nine ranks. Each rank is called a dan 단 (段) or «degree» (as in «third dan» or «third-degree black belt»). The numbering sequence for dan ranks is opposite that of geup ranks: numbering begins at 1st dan (the lowest black-belt rank) and counts upward for higher ranks. A practitioner’s degree is sometimes indicated on the belt itself with stripes, Roman numerals, or other methods.

Some styles incorporate an additional rank between the geup and dan levels, called the «bo-dan» rank—essentially, a candidate rank for black belt promotion. Additionally, the Kukkiwon/WT-style of Taekwondo recognizes a «poom» rank for practitioners under the age of 15: these practitioners have passed dan-level tests but will not receive dan-level rank until age 15. At age 15, their poom rank is considered to transition to equivalent dan rank automatically. In some schools, holders of the poom rank wear a half-red/half-black belt rather than a solid black belt.

To advance from one rank to the next, students typically complete promotion tests in which they demonstrate their proficiency in the various aspects of the art before their teacher or a panel of judges. Promotion tests vary from school to school, but may include such elements as the execution of patterns, which combine various techniques in specific sequences; the breaking of boards to demonstrate the ability to use techniques with both power and control; sparring and self-defense to demonstrate the practical application and control of techniques; physical fitness usually with push-ups and sit-ups; and answering questions on terminology, concepts, and history to demonstrate knowledge and understanding of the art. For higher dan tests, students are sometimes required to take a written test or submit a research paper in addition to taking the practical test.

Promotion from one geup to the next can proceed rapidly in some schools since schools often allow geup promotions every two, three, or four months. Students of geup rank learn the most basic techniques first, and then move on to more advanced techniques as they approach first dan. Many of the older and more traditional schools often take longer to allow students to test for higher ranks than newer, more contemporary schools, as they may not have the required testing intervals. In contrast, promotion from one dan to the next can take years. In fact, some styles impose age or time-in-rank limits on dan promotions. For example, the number of years between one dan promotion to the next may be limited to a minimum of the practitioner’s current dan-rank, so that (for example) a 5th dan practitioner must wait 5 years to test for 6th dan.

Black belt ranks may have titles associated with them, such as «master» and «instructor», but Taekwondo organizations vary widely in rules and standards when it comes to ranks and titles. What holds true in one organization may not hold true in another, as is the case in many martial art systems. For example, achieving first dan ( black belt) ranking with three years’ training might be typical in one organization but considered too quick in another organization, and likewise for other ranks. Similarly, the title for a given dan rank in one organization might not be the same as the title for that dan rank in another organization.

In the International Taekwon-Do Federation, instructors holding 1st to 3rd dan are called Boosabum (부사범 副師範) or assistant instructor, those holding 4th to 6th dan are called Sabum (사범 師範) instructor, those holding 7th to 8th dan are called Sahyun (사현 師賢) or master, and those holding 9th dan are called Saseong (사성 師聖) or grandmaster.[40] This system does not, however, necessarily apply to other Taekwondo organizations.

In the American Taekwondo Association, instructor designations are separate from rank. Black belts may be designated as an instructor trainee (red, white and blue collar), specialty trainer (red and black collar), certified trainer (black-red-black collar) and certified instructor (black collar). After a one-year waiting period, instructors who hold the sixth dan are eligible for the title of Master. Seventh dan black belts are eligible for the title Senior Master and eighth dan black belts are eligible for the title Chief Master.

In WT/Kukki-Taekwondo, instructors holding 1st. to 3rd. dan are considered assistant instructors (kyosa-nim), are not yet allowed to issue ranks, and are generally thought of as still having much to learn. Instructors who hold a 4th. to 6th. dan are considered master instructors (sabum-nim), and are allowed to grade students to color belt ranks from 4th. dan, and to black belt/dan-ranks from 6th. dan. Those who hold a 7th–9th dan are considered Grandmasters. These ranks also hold an age requirement of 40+.[41] In this style, a 10th dan rank is sometimes awarded posthumously for practitioners with a lifetime of demonstrable contributions to the practice of Taekwondo.

Historical influences[edit]

The oldest Korean martial arts were an amalgamation of unarmed combat styles developed by the three rival Korean Kingdoms of Goguryeo, Silla, and Baekje,[42] where young men were trained in unarmed combat techniques to develop strength, speed, and survival skills. The most popular of these techniques were ssireum, subak, and Taekkyon. The Northern Goguryeo kingdom was a dominant force in Northern Korea and North Eastern China prior to the 1st century CE, and again from the 3rd century to the 6th century. Before the fall of the Goguryeo Dynasty in the 6th century, the Silla Kingdom asked for help in training its people for defence against pirate invasions. During this time a few select Silla warriors were given training in Taekkyon by the early masters from Goguryeo. These Silla warriors then became known as Hwarang or «blossoming knights». The Hwarang set up a military academy for the sons of royalty in Silla called Hwarang-do {花郎徒}, which means «flower-youth corps». The Hwarang studied Taekkyon, history, Confucian philosophy, ethics, Buddhist morality, social skills, and military tactics. The guiding principles of the Hwarang warriors were based on Won Gwang’s five codes of human conduct and included loyalty, filial duty, trustworthiness, valour, and justice.

[43]

In spite of Korea’s rich history of ancient and martial arts, Korean martial arts faded during the late Joseon Dynasty. Korean society became highly centralized under Korean Confucianism, and martial arts were poorly regarded in a society whose ideals were epitomized by its scholar-kings.[44] Formal practices of traditional martial arts such as subak and Taekkyon were reserved for sanctioned military uses. However, Taekkyon persisted into the 19th century as a folk game during the May-Dano festival, and was still taught as the formal military martial art throughout the Joseon Dynasty.[42]

Early progenitors of Taekwondo—the founders of the nine original kwans—who were able to study in Japan were exposed to Japanese martial arts, including karate, judo, and kendo,[45] while others were exposed to the martial arts of China and Manchuria, as well as to the indigenous Korean martial art of Taekkyon.[9][46][47][48] Hwang Kee founder of Moo Duk Kwan, further incorporated elements of Korean Gwonbeop from the Muye Dobo Tongji into the style that eventually became Tang Soo Do.

The historical influences of Taekwondo is controversial with a split between two schools of thought: traditionalism and revisionism. Traditionalism holds that the origins of Taekwondo can be traced through Korean martial arts while revisionism, which has become the prevailing theory, argues that Taekwondo is rooted in Karate.[49] Traditionalism has mainly been supported by the Korean government as a concerted effort to divorce Korean martial arts from their Japanese past to give Korean a «legitimate cultural past».[50]

Philosophy[edit]

Different styles of Taekwondo adopt different philosophical underpinnings. Many of these underpinnings however refer back to the Five Commandments of the Hwarang as a historical referent. For example, Choi Hong-hi expressed his philosophical basis for Taekwondo as the Five Tenets of Taekwondo:[51]

- Courtesy (yeui / 예의, 禮儀)

- Integrity (yeomchi / 염치, 廉恥)

- Perseverance (innae / 인내, 忍耐)

- Self-control (geukgi / 극기, 克己)

- Indomitable spirit (baekjeolbulgul / 백절불굴, 百折不屈)

These tenets are further articulated in a Taekwondo oath, also authored by Choi:

- I shall observe the tenets of Taekwondo

- I shall respect the instructor and seniors

- I shall never misuse Taekwondo

- I shall be a champion of freedom and justice

- I shall build a more peaceful world

Modern ITF organizations have continued to update and expand upon this philosophy.[52][53]

The World Taekwondo Federation (WTF) also refers to the commandments of the Hwarang in the articulation of its Taekwondo philosophy.[54] Like the ITF philosophy, it centers on the development of a peaceful society as one of the overarching goals for the practice of Taekwondo. The WT’s stated philosophy is that this goal can be furthered by adoption of the Hwarang spirit, by behaving rationally («education in accordance with the reason of heaven»), and by recognition of the philosophies embodied in the taegeuk (the yin and the yang, i.e., «the unity of opposites») and the sam taegeuk (understanding change in the world as the interactions of the heavens, the Earth, and Man). The philosophical position articulated by the Kukkiwon is likewise based on the Hwarang tradition.[55]

Competition[edit]

Sparring in a Taekwondo class

Taekwondo competition typically involves sparring, breaking, and patterns; some tournaments also include special events such as demonstration teams and self-defense (hosinsul). In Olympic Taekwondo competition, however, only sparring (using WT competition rules) is performed.[56]

There are two kinds of competition sparring: point sparring, in which all strikes are light contact and the clock is stopped when a point is scored; and Olympic sparring, where all strikes are full contact and the clock continues when points are scored. Sparring involves a Hogu, or a chest protector, which muffles any kick’s damage to avoid serious injuries. Helmets and other gear are provided as well. Though other systems may vary, a common point system works like this: one point for a regular kick to the Hogu, two for a turning behind the kick, three for a back kick, and four for a spinning kick to the head.

World Taekwondo (WT) Competition[edit]

Official WT trunk protector (hogu), forearm guards and shin guards

Under World Taekwondo (WT, formerly WTF) and Olympic rules, sparring is a full-contact event, employing a continuous scoring system where the fighters are allowed to continue after scoring each technique, taking place between two competitors in either an area measuring 8 meters square or an octagon of similar size.[57] Competitors are matched within gender and weight division—eight divisions for World Championships that are condensed to four for the Olympics. A win can occur by points, or if one competitor is unable to continue (knockout). However, there are several decisions that can lead to a win, as well, including superiority, withdrawal, disqualification, or even a referee’s punitive declaration.[58] Each match consists of three two-minute rounds, with one minute rest between rounds, though these are often abbreviated or shortened for some junior and regional tournaments.[57] Competitors must wear a hogu, head protector, shin pads, foot socks, forearm guards, hand gloves, a mouthpiece, and a groin cup. Tournaments sanctioned by national governing bodies or the WT, including the Olympics and World Championship, use electronic hogus, electronic foot socks, and electronic head protectors to register and determine scoring techniques, with human judges used to assess and score technical (spinning) techniques and score punches.[57]

Points are awarded for permitted techniques delivered to the legal scoring areas as determined by an electronic scoring system, which assesses the strength and location of the contact. The only techniques allowed are kicks (delivering a strike using an area of the foot below the ankle), punches (delivering a strike using the closed fist), and pushes. In some smaller tournaments, and in the past, points were awarded by three corner judges using electronic scoring tallies. All major national and international tournaments have moved fully (as of 2017) to electronic scoring, including the use of electronic headgear. This limits corner judges to scoring only technical points and punches. Some believe that the new electronic scoring system reduces controversy concerning judging decisions,[59] but this technology is still not universally accepted.[60] In particular, the move to electronic headgear has replaced controversy over judging with controversy over how the technology has changed the sport. Because the headgear is not able to determine if a kick was a correct Taekwondo technique, and the pressure threshold for sensor activation for headgear is kept low for safety reasons, athletes who improvised ways of placing their foot on their opponents head were able to score points, regardless of how true to Taekwondo those techniques were.[61]

Techniques are divided into three categories: scoring techniques (such as a kick to the hogu), permitted but non-scoring techniques (such as a kick that strikes an arm), and not-permitted techniques (such as a kick below the waist).

- A punch that makes strong contact with the opponent’s hogu scores 1 point. The punch must be a straight punch with arm extended; jabs, hooks, uppercuts, etc. are permitted but do not score. Punches to the head are not allowed.

- A regular kick (no turning or spinning) to the hogu scores 2 points.

- A regular kick (no turning or spinning) to the head scores 3 points

- A technical kick (a kick that involves turning or spinning) to the hogu scores 4 points.

- A technical kick to the head scores 5 points.

- As of October 2010, 4 points were awarded if a turning kick was used to execute this attack. As of June 2018, this was changed to 5 points.[62]

The referee can give penalties at any time for rule-breaking, such as hitting an area not recognized as a target, usually the legs or neck. Penalties, called «Gam-jeom» are counted as an addition of one point for the opposing contestant. Following 10 «Gam-jeom» a player is declared the loser by referee’s punitive declaration[57]

At the end of three rounds, the competitor with most points wins the match. In the event of a tie, a fourth «sudden death» overtime round, sometimes called a «Golden Point», is held to determine the winner after a one-minute rest period. In this round, the first competitor to score a point wins the match. If there is no score in the additional round, the winner is decided by superiority, as determined by the refereeing officials[62] or number of fouls committed during that round.

If a competitor has a 20-point lead at the end of the second round or achieves a 20-point lead at any point in the third round, then the match is over and that competitor is declared the winner.[57]

In addition to sparring competition, World Taekwondo sanctions competition in poomsae or forms, although this is not an Olympic event. Single competitors perform a designated pattern of movements, and are assessed by judges for accuracy (accuracy of movements, balance, precision of details) and presentation (speed and power, rhythm, energy), both of which receive numerical scores, with deductions made for errors.[63] Pair and team competition is also recognized, where two or more competitors perform the same form at the same time. In addition to competition with the traditional forms, there is experimentation with freestyle forms that allow more creativity.[63]

The World Taekwondo Federation directly sanctions the following competitions:[64]

- World Taekwondo Poomsae Championships

- World Taekwondo Championships

- World Para Taekwondo Championships (since 2009)[65]

- World Taekwondo Cadet Championships

- World Taekwondo Junior Championships

- World Taekwondo Team Championships

- World Taekwondo Para Championships

- World Taekwondo Grand Prix

- World Taekwondo Grand Slam

- World Taekwondo Beach Championships

- Olympic Games

- Paralympic Games (debut in 2020 Tokyo Paralympics)[66]

International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF) Competition[edit]

Common styles of ITF point sparring equipment

The International Taekwon-Do Federation’s sparring rules are similar to the WT’s rules but differ in several aspects.

- Hand attacks to the head are allowed.[67]

- The competition is not full contact, and excessive contact is not allowed.

- Competitors are penalized with disqualification if they injure their opponent and he can no longer continue (knockout).

- The scoring system is:

- 1 point for Punch to the body or head.

- 2 points for Jumping kick to the body or kick to the head, or a jumping punch to the head

- 3 points for Jumping kick to the head

- The competition area is 9×9 meters for international events.

Competitors do not wear the hogu (although they are required to wear approved foot and hand protection equipment, as well as optional head guards). This scoring system varies between individual organisations within the ITF; for example, in the TAGB, punches to the head or body score 1 point, kicks to the body score 2 points, and kicks to the head score 3 points.

A continuous point system is utilized in ITF competition, where the fighters are allowed to continue after scoring a technique. Excessive contact is generally not allowed according to the official ruleset, and judges penalize any competitor with disqualification if they injure their opponent and he can no longer continue (although these rules vary between ITF organizations). At the end of two minutes (or some other specified time), the competitor with more scoring techniques wins.

Fouls in ITF sparring include: attacking a fallen opponent, leg sweeping, holding/grabbing, or intentional attack to a target other than the opponent.[68]

ITF competitions also feature performances of patterns, breaking, and ‘special techniques’ (where competitors perform prescribed board breaks at great heights).

Multi-discipline competition[edit]

Some organizations deliver multi-discipline competitions, for example the British Student Taekwondo Federation’s inter-university competitions, which have included separate WT rules sparring, ITF rules sparring, Kukkiwon patterns and Chang-Hon patterns events run in parallel since 1992.[69]

Other organizations[edit]

American Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) competitions are very similar, except that different styles of pads and gear are allowed.[70]

Apart from WT and ITF tournaments, major Taekwondo competitions (all featuring WT Taekwondo only) include:

- African Games

- Asian Games

- European Games

- Pacific Games

- Pan American Games

- Universiade

Taekwondo is also an optional sport at the Commonwealth Games.

Weight divisions[edit]

The following weight divisions are in effect due to the WT[71] and ITF[72] tournament rules and regulations:

| Olympics | |

|---|---|

|

Male |

Female |

| −58 kg | −49 kg |

| −68 kg | −57 kg |

| −80 kg | −67 kg |

| +80 kg | +67 kg |

| WT Male Championships |

|

|---|---|

|

Juniors |

Adults |

| −45 kg | −54 kg |

| −48 kg | |

| −51 kg | |

| −55 kg | |

| −59 kg | −58 kg |

| −63 kg | −63 kg |

| −68 kg | −68 kg |

| −73 kg | −74 kg |

| −78 kg | |

| +78 kg | −80 kg |

| −87 kg | |

| +87 kg |

| WT Female Championships |

|

|---|---|

|

Juniors |

Adults |

| −42 kg | −46 kg |

| −44 kg | |

| −46 kg | −49 kg |

| −49 kg | |

| −52 kg | −53 kg |

| −55 kg | |

| −59 kg | −57 kg |

| −63 kg | −62 kg |

| −68 kg | −67 kg |

| +68 kg | −73 kg |

| +73 kg |

| ITF Male Championships | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Juniors |

Adults (18—39 yrs) |

Veterans over 40 |

Veterans over 50 |

| −45 kg | −50 kg | −64 kg | −66 kg |

| −51 kg | −57 kg | ||

| −57 kg | −64 kg | −73 kg | |

| −63 kg | −71 kg | ||

| −69 kg | −78 kg | −80 kg | −80 kg |

| −75 kg | −85 kg | −90 kg | |

| +75 kg | +85 kg | +90 kg | +80 kg |

| ITF Female Championships | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Juniors |

Adults (18—39 yrs) |

Veterans over 40 |

Veterans over 50 |

| −40 kg | −45 kg | −54 kg | −60 kg |

| −46 kg | −51 kg | ||

| −52 kg | −57 kg | −61 kg | |

| −58 kg | −63 kg | ||

| −64 kg | −69 kg | −68 kg | −75 kg |

| −70 kg | −75 kg | −75 kg | |

| +70 kg | +75 kg | +75 kg | +75 kg |

Korean Taekwondo vocabulary[edit]

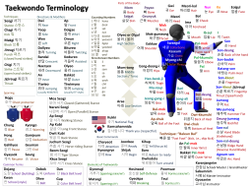

Some common Taekwondo terminology and parts of the body

In Taekwondo schools—even outside Korea—Korean language commands and vocabulary are often used. Korean numerals may be used as prompts for commands or for counting repetition exercises. Different schools and associations will use different vocabulary, however, and may even refer to entirely different techniques by the same name. As one example, in Kukkiwon/WT-style Taekwondo, the term ap seogi refers to an upright walking stance, while in ITF/Chang Hon-style Taekwondo ap seogi refers to a long, low, front stance. Korean vocabulary commonly used in Taekwondo schools includes:

| Basic Commands | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul (한글) | Hanja (한자/漢字) | Revised Romanization |

| Attention | 차렷 | Charyeot | |

| Ready | 준비 | 準備 | Junbi |

| Begin | 시작 | 始作 | Sijak |

| Finish / Stop | 그만 | Geuman | |

| Bow | 경례 | 敬禮 | Gyeonglye |

| Resume / Continue | 계속 | 繼續 | Gyesok |

| Return to ready | 바로 | Baro | |

| Relax / At ease | 쉬어 | Swieo | |

| Rest / Take a break | 휴식 | 休息 | Hyusik |

| Turn around / About face | 뒤로돌아 | Dwirodora | |

| Yell | 기합 | 氣合 | Gihap |

| Look / Focus | 시선 | 視線 | Siseon |

| By the count | 구령에 맞춰서 | 口令에 맞춰서 | Guryeong-e majchwoseo |

| Without count | 구령 없이 | 口令 없이 | Guryeong eobs-i |

| Switch feet | 발 바꿔 | Bal bakkwo | |

| Dismissed | 해산 | 解散 | Haesan |

| Hand Techniques | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul (한글) | Hanja (한자/漢字) | Revised Romanization |

| Hand Techniques | 수 기 | 手技 | Su gi |

| Attack / Strike / Hit | 공격 | 攻擊 | Gong-gyeog |

| Strike | 치기 | Chigi | |

| Block | 막기 | Magki | |

| Punch/hit | 권 | 拳 | Gwon |

| Punch | 지르기 | Jireugi | |

| Middle punch | 중 권 | 中拳 | Jung gwon |

| Middle Punch | 몸통 지르기 | Momtong jireugi | |

| Back fist | 갑 권 | 甲拳 / 角拳 | Gab gwon |

| Back fist | 등주먹 | Deungjumeog | |

| Knife hand (edge) | 수도 | 手刀 | Su Do |

| Knife hand (edge) | 손날 | Son Kal | |

| Thrust / spear | 관 | 貫 | Gwan |

| Thrust / spear | 찌르기 | Jjileugi | |

| Spear hand | 관 수 | 貫手 | Gwan su |

| Spear hand (lit. fingertip) | 손끝 | Sonkkeut | |

| Ridge hand | 역 수도 | 逆手刀 | Yeog su do |

| Ridge hand (lit. reverse hand blade) | 손날등 | Sonnaldeung | |

| Hammer fist | 권도 | 拳刀 / 拳槌 | Gweon do |

| Pliers hand | 집게 손 | Jibge son | |

| Palm heel | 장관 | 掌貫 | Jang gwan |

| Palm heel | 바탕손 | Batangson | |

| Elbow | 팔꿈 | Palkkum | |

| Gooseneck | 손목 등 | Sonmog deung | |

| Side punch | 횡진 공격 | 橫進攻擊 | Hoengjin gong gyeog |

| Side punch | 옆 지르기 | Yeop jileugi | |

| Mountain block | 산 막기 | 山막기 | San maggi |

| One finger fist | 일 지 권 | 一指拳 | il ji gwon |

| 1 finger spear hand | 일 지관 수 | 一指貫手 | il ji gwan su |

| 2 finger spear hand | 이지관수 | 二指貫手 | i ji gwan su |

| Double back fist | 장갑권 | 長甲拳 | Jang gab gwon |

| Double hammer fist | 장 권도 | 長拳刀 | Jang gwon do |

| Foot Techniques | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul (한글) | Hanja (한자/漢字) | Revised Romanization |

| Foot Techniques | 족기 | 足技 | Jog gi |

| Kick | 차기 | Chagi | |

| Front snap kick | 앞 차기 | Ap chagi | |

| …also Front snap kick | 앞 차넣기 | Ap chaneohgi | |

| …also Front snap kick | 앞 뻗어 차기 | Ap ppeod-eo chagi | |

| Inside-out heel kick or outside crescent kick | 안에서 밖으로 차기 | An-eseo bakk-eulo chagi | |

| Outside-in heel kick or inside crescent kick | 밖에서 안으로 차기 | Baggeso aneuro chagi | |

| Stretching front kick | 앞 뻗어 올리 기 | Ap ppeod-eo olli gi | |

| Roundhouse kick | 돌려 차기 | Dollyeo chagi | |

| …also Roundhouse kick | Ap dollyeo chagi | ||

| Side kick | 옆 차기 | Yeop chagi | |

| …also Snap Side kick | 옆 뻗어 차기 | Yeop ppeod-eo chagi | |

| Hook kick | 후려기 차기 | Hulyeogi chagi | |

| …also hook kick | 후려 차기 | Huryeo chagi | |

| Back kick | 뒤 차기 | Dwi chagi | |

| …also Spin Back kick | 뒤 돌려 차기 | Dwi dollyeo chagi | |

| Spin hook kick | 뒤 돌려 후려기 차기 | Dwi dollyeo hulyeogi chagi | |

| Knee strike | 무릎 차기 | Mu reup chagi | |

| Reverse round kick | 빗 차기 | Bit chagi |

| Stances | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul (한글) | Hanja (한자/漢字) | Revised Romanization |

| Stances | 자세 | 姿勢 | Seogi (stance) or Jase (posture) |

| Ready stance | 준비 자세 | 準備 姿勢 | Junbi seogi (or jase) |

| Front Stance | 전굴 자세 | 前屈 姿勢 | Jeongul seogi (or jase) |

| Back Stance | 후굴 자세 | 後屈 姿勢 | Hugul seogi (or jase) |

| Horse-riding Stance | 기마 자세 | 騎馬 姿勢 | Gima seogi (or jase) |

| …also Horse-riding Stance | 기마립 자세 | 騎馬立 姿勢 | Gimalip seogi (or jase) |

| …also Horse-riding Stance | 주춤 서기 | Juchum seogi | |

| Side Stance | 사고립 자세 | 四股立 姿勢 | Sagolib seogi (or jase) |

| Cross legged stance | 교차 립 자세 | 交(叉/差)立 姿勢 | Gyocha lib seogi (or jase) |

| Technique Direction | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul (한글) | Hanja (한자/漢字) | Revised Romanization |

| Moving forward | 전진 | 推進 | Jeonjin |

| Backing up / retreat | 후진 | 後進 | Hujin |

| Sideways/laterally | 횡진 | 橫進 | Hoengjin |

| Reverse (hand/foot) | 역진 | 逆進 | Yeogjin |

| Lower | 하단 | 下段 | Hadan |

| Middle | 중단 | 中段 | Jungdan |

| Upper | 상단 | 上段 | Sangdan |

| Two handed | 쌍수 | 雙手 | Ssangsu |

| Both hands | 양수 | 兩手 | Yangsu |

| Lowest | 최 하단 | 最下段 | Choe hadan |

| Right side | 오른 쪽 | Oleun jjog | |

| Left side | 왼 쪽 | Oen jjog | |

| Other side/Twist | 틀어 | Teul-eo | |

| Inside-outside | 안에서 밖으로 | An-eseo bakk-eulo | |

| Outside inside | 밖에서 안으로 | Bakk-eseo an-eulo | |

| Jumping / 2nd level | 이단 | 二段 | Idan |

| Hopping / Skipping | 뜀을 | Ttwim-eul | |

| Double kick | 두 발 | Du bal | |

| Combo kick | 연속 | 連續 | Yeonsog |

| Same foot | 같은 발 | Gat-eun bal |

| Titles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul (한글) | Hanja (한자/漢字) | Revised Romanization |

| Founder/President | 관장 님 | 館長님 | Gwanjang nim |

| Master instructor | 사범 님 | 師範님 | Sabeom nim |

| Teacher | 교사 님 | 敎師님 | Gyosa nim |

| Black Belt | 단 | 段 | Dan |

| Student or Color Belt | 급 | 級 | Geup |

| Master level | 고단자 | 高段者 | Godanja |

| Other/Miscellaneous | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| English | Hangul (한글) | Hanja (한자/漢字) | Revised Romanization |

| School | 관 | 館 | Gwan (kwan) |

| Country Flag | 국기 | 國旗 | Guggi |

| Salute the flag | 국기 배례 | 國旗 拜禮 | Guggi baerye |

| Pay respect / bow | 경례 | 敬禮 | Gyeongnye |

| Moment of silence | 묵념 | 默念 | Mugnyeom |

| Sit down! | 앉아! | Anj-a! | |

| Thank you | 감사합니다 | 感謝합니다 | Gamsa habnida |

| Informal thank you | 고맙습니다 | Gomabseubnida | |

| You’re welcome | 천만에요 | Cheonman-eyo | |

| Uniform | 도복 | 道服 | Dobok |

| Belt | 띠 | 帶 | Tti |

| Studio / School / Gym | 도장 | 道場 | Dojang |

| Test | 심사 | 審査 | Simsa |

| Self Defense | 호신술 | 護身術 | Hosinsul |

| Sparring (Kukkiwon/WT-style) | 겨루기 | Gyeorugi | |

| …also Sparring (Chang Hon/ITF-style) | 맞서기 | Matseogi | |

| …also Sparring | 대련 | 對練 | Daelyeon |

| Free sparring | 자유 대련 | 自由 對練 | Jayu daelyeon |

| Ground Sparring | 좌 대련 | 座 對練 | Jwa daelyeon |

| One step sparring | 일 수식 대련 | 一數式 對練 | il su sig daelyeon |

| Three step sparring | 삼 수식 대련 | 三數式 對練 | Sam su sig daelyeon |

| Board Breaking | 격파 | 擊破 | Gyeog pa |

Notable practitioners[edit]

See also[edit]

- Para Taekwondo

- Tae Kwon Do Life Magazine

- Taekwondo student oath

- Taekwondo in India

Notes[edit]

- ^ Namely Shotokan and Shudokan, which served as basis for styles practiced by the original nine Kwans.

- ^ Used by Chung Do Kwan and Moo Duk Kwan

- ^ Used by Yun Mu Kwan/Jidokwan and YMCA Kwon Bop Bu/Chang Moo Kwan

- ^ Was an early name of Taekwondo before Choi Hong-hi managed to convince the organization to adopt the name Taekwondo instead.

- ^ Tang Soo Do, Chung Do Kwan

References[edit]

- ^ Kang, Won Sik; Lee, Kyong Myung (1999). A Modern History of Taekwondo. Seoul: Pogyŏng Munhwasa. ISBN 978-89-358-0124-4.

- ^ «kung fu influence on taekwondo». White Dragon Dojang.

- ^ «tae kwon do». OxfordDictionaries.com. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ «tae kwon do». Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ «tae kwon do». Cambridge English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ «taekwondo — Wiktionary». en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- ^ «태권도». terms.naver.com (in Korean). Retrieved 2021-04-17.

- ^ «Flying Kicks: The Roots of Taekwondo and the Future of Martial Arts». Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ a b «Brief History of Taekwondo». Long Beach Press-Telegram. 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kang, Won Sik; Lee, Kyong Myung (1999). A Modern History of Taekwondo. Seoul: Pogyŏng Munhwasa. ISBN 978-89-358-0124-4.

- ^ «Korea officially designates taekwondo as nat’l martial art». www.koreaherald.com. 2 April 2018.

- ^ «Korea: Korean Martial Arts». www.koreaorbit.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Gillis, Alex (2008). A Killing Art: The Untold History of Tae Kwon Do. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1550228250.

- ^ Lo, David. «Taekwon-do: A Broken Family?» (PDF). Thesis prepared for 4th dan granting requirements. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 1, 2017.

The President was amazed and asked General Choi what the new martial art is called. President Rhee was a nationalist, hated the Japanese and would not approve the soldiers practicing Japanese martial arts such as Tang Soo Do or Korean Karate. Someone said to the President that it was Tang Soo Do. ‘No, it’s T’aekkyon’ the President countered. The president later instructed General Choi to teach the T’aekkyon martial art to more Korean soldiers.

- ^ テコンドーの歴史も2千年? 空手の親? 消された創始者(1/3). KoreaWorldTimes (in Japanese). 2021-07-23. Retrieved 2021-09-22.

- ^ «General Choi, utilizing both his advanced education and Calligraphy skills that involved extensive knowledge of Chinese characters and language, searched for and later conceived of the new term Tae Kwon Do. This label more accurately reflected the shifting emphasis on the use of the legs for kicking». General Choi Taekwon-do Association (India) website.

- ^ «Interview with Nam Tae-Hi making it clear that Tae Kwon Do came from Korean Karate (also known as «Shotokan Karate,» «Tang Soo Do» and «Kong Soo Do»). At a martial arts meeting in 1955, Choi presented a fictional argument connecting Taekwon-Do to Taekkyon, an old martial art». 2011.

- ^ Lo, David. «Nam and General Choi faced a dilemma as they could not teach the Koreans Karate and call it Taekkyeon. Eventually they took the best of Tang Soo Do and added some Taekkyeon. They needed a new name urgently but the President liked the name Taekkyon» (PDF). Thesis prepared for 4th dan granting requirements. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 1, 2017.

- ^ «World Taekwondo Federation changes name over ‘negative connotations’«. BBC Sport. 2017-06-24. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ^ a b «Kukkiwon History». Kukkiwon.or.kr. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ Williams, Bob (23 June 2010). «Taekwondo set to join 2018 Commonwealth Games after ‘category two’ classification». The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 16 October 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- ^ «WT Competition Rules». WorldTaekwondo.org. Retrieved September 7, 2014.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Choi, Hong Hi (1983). Encyclopedia of Taekwon-Do. International Taekwon-Do Federation. ASIN B008UAO292.

- ^ «ITF Theory of Power». Tkd.co.uk. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ Kim, Sang H. (2002). Martial Arts Instructors Desk Reference: A Complete Guide to Martial Arts Administration. Turtle Press. ASIN B001GIOGL4.

- ^ «Different styles of Taekwondo». ActiveSG.

- ^ «ITF Austria». itf-tkd.org. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ^ «ITF United Kingdom». Itf-administration.com. Retrieved September 16, 2014.

- ^ «ITF Spain». taekwondoitf.org. Archived from the original on January 23, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2020.

- ^ «ATA History». Ataon;ine.com. Archived from the original on September 28, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ «The Jhoon Rhee Story». Jhoonrhee.com. Archived from the original on February 18, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ «WTF History». Worldtaekwondofederation.net. Archived from the original on October 31, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ^ «The Martial Art». British Taekwondo. Archived from the original on 2021-12-02. Retrieved 2022-02-18.

- ^ «American Taekwondo Association | Martial Arts, Karate, Tae Kwon Do, Tae-Kwon-Do». Ataonline.com. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ Website, A. «Blue Cottage Taekwon-Do». Bluecottagetkd.com. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ «Main». Gtftaekwondo.com. Archived from the original on 2015-06-27. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ «World Taekwondo Headquarters». Kukkiwon.or.kr. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ «Home». Jhoon Rhee Tae Kwon Do—Arlington. Retrieved 2015-06-26.

- ^ «U-Nam The Forgotten ITF Pattern» (PDF). Blue Cottage Taekwondo. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 23, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ^ Choi, H. H. (1993): Taekwon-Do: The Korean art of self-defence, 3rd ed. (Vol. 1, p. 122). Mississauga: International Taekwon-Do Federation.

- ^ Kukkiwon (2005). Kukkiwon Textbook. Seoul: Osung. ISBN 978-8973367504.

- ^ a b Capener, Steven D. (2000). Kim, H. Edward (ed.). Taekwondo: The Spirit of Korea (portions of). Korea: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, Republic of Korea. Archived from the original on 2006-12-02. Retrieved 2006-12-18.

Korea has a long history of martial arts stretching well back into ancient times. Written historical records from the early days of the Korean peninsula are sparse, however, there are a number of well-preserved archaeological artefacts that tell stores of Korea’s early martial arts.», «taekwondo leaders started to experiment with a radical new system that would result in the development of a new martial sport different from anything ever seen before. This new martial sport would bear some important similarities to the traditional Korean game of taekkyon.

- ^ Seth, Michael J. (2010). A History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-0742567160.

- ^ Cummings, B. (2005). Korea’s Place in the Sun. New York, NY: W.W. Norton.

- ^ Park, S. W. (1993): About the author. In H. H. Choi: Taekwon-Do: The Korean art of self-defence, 3rd ed. (Vol. 1, pp. 241–274). Mississauga: International Taekwon-Do Federation

- ^ Glen R. Morris. «The History of Taekwondo».

- ^ Cook, Doug (2006). «Chapter 3: The Formative Years of Taekwondo». Traditional Taekwondo: Core Techniques, History and Philosophy. Boston: YMAA Publication Center. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-59439-066-1.

- ^ Choi Hong-hi (1999). «ITF Information interviews with General Choi». The Condensed Encyclopedia Fifth Edition. Archived from the original on 2009-09-18.

Young Choi’s father sent him to study calligraphy under one of the most famous teachers in Korea, Mr Han II Dong. Han, in addition to his skills as a calligrapher, was also a master of taekkyeon, the ancient Korean art of foot fighting. The teacher, concerned over the frail condition of his new student, began teaching him the rigorous exercises of taekkyeon to help build up his body.

- ^ Park, Cindy; Kim, Tae Yang (2016-06-12). «Historical Views on the Origins of Korea’s Taekwondo». The International Journal of the History of Sport. 33 (9): 978–989. doi:10.1080/09523367.2016.1233867. ISSN 0952-3367. S2CID 151514066.

- ^ Moenig, Udo. «The Influence of Korean Nationalism on the Formational Process of T’aekwŏndo in South Korea». ao.81.2.10moe. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ S. Benko, James. «Grand Master, Ph.D.» The Tenants Of Tae Kwon Do. ITA Institute. Retrieved 13 March 2013.

- ^ «ITF More Culture». Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ «ITF Philosophy». Tkd.otf.org. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ «WTF Philosophy». Worldtaekwondofederation.net. Archived from the original on November 3, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ «Kukkiwon Philosophy». Kukkiwon.or.kr. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- ^ World Taekwondo Federation (2004). «Kyorugi rules». Rules. WorldTaekwondo.org. Archived from the original on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2007-08-11.

- ^ a b c d e «WORLD TAEKWONDO FEDERATION COMPETITION RULES & INTERPRETATION» (PDF). World Taekwondo. October 1, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2017.

- ^ «Taekwondo Rules» (PDF). martialartsweaponstraining.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-03.(24 June 2017, p. 38)

- ^ Gomez, Brian (August 23, 2009). «New taekwondo scoring system reduces controversy». The Gazette. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-05-06.

- ^ «British taekwondo chief says new judging system is far from flawless». morethanthegames.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010.

- ^ Press, MARIA CHENG Associated. «Is that a kick? Taekwondo fighters devise new ways to score». sandiegouniontribune.com. Retrieved 2017-10-02.

- ^ a b World Taekwondo Federation (Oct 7, 2010): Competition rules & interpretation[permanent dead link] (7 October 2010, pp. 31–32). Retrieved on 27 November 2010.

- ^ a b «WORLD TAEKWONDO FEDERATION POOMSAE COMPETITION RULES & INTERPRETATION» (PDF). World Taekwondo. October 1, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 2, 2017.

- ^ «Main—World Taekwondo Federation». World Taekwondo Federation. Retrieved 2016-04-30.

- ^ «information». Archived from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ «Paralympic Sports : Taekwondo|The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games». The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ «itf-information.com». Archived from the original on 2012-06-13. Retrieved 2012-01-26.

- ^ ITF World Junior & Senior Tournament Rules—Rules and Regulations

- ^ «30 Years of the Student National Taekwondo Championships». Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ «AAU Taekwondo > Rules/Info > Rules Handbook > 2015 AAU Taekwondo Handbook Divided By Sections». Aautaekwondo.org. Archived from the original on 2015-06-19. Retrieved 2015-06-13.

- ^ Taekwondo World Qualification Tournament Outline, Archived February 19, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, page 3.

- ^ ITF TOURNAMENT RULES, pages 21-22.

External links[edit]

Look up taekwondo in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Taekwondo.

- Kukkiwon’s Guide to Technical Terminology in Taekwondo

A taekwondo contest at the 2016 Summer Olympics |

|

| Also known as | TKD, Tae Kwon Do, Tae Kwon-Do, Taekwon-Do, Tae-Kwon-Do |

|---|---|

| Focus | Striking, kicking |

| Country of origin | Korea |

| Creator | No single creator; a collaborative effort by representatives from the original nine Kwans, initially supervised by Choi Hong-hi.[1] |

| Famous practitioners | (see notable practitioners) |

| Parenthood | Mainly Taekkyon and Karate,[a] and slight influence of Chinese martial arts[2] |

| Olympic sport | Since 2000 (World Taekwondo) |

| Highest governing body | World Taekwondo (South Korea) |

|---|---|

| First played | Korea, 1940s |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Full-contact (WT), Light and medium-contact (ITF, ITC, ATKDA, GBTF, GTF, ATA, TI,TCUK, TAGB) |

| Mixed-sex | Yes |

| Type | Combat sport |

| Equipment | Hogu, Headgear, |

| Presence | |

| Country or region | Worldwide |

| Olympic | Since 2000 |

| Paralympic | Since 2020 |

| World Games | 1981–1993 |

| Taekwondo | |

| Hangul |

태권도 |

|---|---|

| Hanja |

跆拳道 |

| Revised Romanization | taegwondo |

| McCune–Reischauer | t’aekwŏndo |

| IPA | [t̪ʰɛ.k͈wʌ̹n.d̪o] ( |

Taekwondo, Tae Kwon Do or Taekwon-Do (;[3][4][5] Korean: 태권도/跆拳道 [t̪ʰɛ.k͈wʌ̹n.d̪o] (listen)) is a Korean form of martial arts involving punching and kicking techniques, with emphasis on head-height kicks, spinning jump kicks, and fast kicking techniques. The literal translation for tae kwon do is «kicking», «punching», and «the art or way of».[6] They are a kind of martial arts in which one attacks or defends with hands and feet anytime or anywhere, with occasional use of weapons. The physical training undertaken in Taekwondo is purposeful and fosters strength of mind through mental armament.[7]

Taekwondo practitioners wear a uniform, known as a dobok. It is a combat sport and was developed during the 1940s and 1950s by Korean martial artists with experience in martial arts such as karate, Chinese martial arts, and indigenous Korean martial arts traditions such as Taekkyon, Subak, and Gwonbeop.[8][9]

The oldest governing body for Taekwondo is the Korea Taekwondo Association (KTA), formed in 1959 through a collaborative effort by representatives from the nine original kwans, or martial arts schools, in Korea. The main international organisational bodies for Taekwondo today are the International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF), founded by Choi Hong-hi in 1966, and the partnership of the Kukkiwon and World Taekwondo (WT, formerly World Taekwondo Federation or WTF), founded in 1972 and 1973 respectively by the Korea Taekwondo Association.[10] Gyeorugi ([kjʌɾuɡi]), a type of full-contact sparring, has been an Olympic event since 2000. In 2018, the South Korean government officially designated Taekwondo as Korea’s national martial art.[11]

The governing body for Taekwondo in the Olympics and Paralympics is World Taekwondo.

History[edit]

Beginning in 1945, shortly after the end of World War II and Japanese Occupation, new martial arts schools called kwans opened in Seoul. These schools were established by Korean martial artists with backgrounds in Japanese[12] and Chinese martial arts. At the time, indigenous disciplines (such as Taekkyeon) were being forgotten, due to years of decline and repression by the Japanese colonial government. The umbrella term traditional Taekwondo typically refers to the martial arts practiced by the kwans during the 1940s and 1950s, though in reality the term «Taekwondo» had not yet been coined at that time, and indeed each kwan (school) was practicing its own unique style of the Korean art.

In 1952, South Korean president Syngman Rhee witnessed a martial arts demonstration by ROK Army officers Choi Hong-hi and Nam Tae-hi from the 29th Infantry Division. He misrecognized the technique on display as Taekkyeon,[13][14][15] and urged martial arts to be introduced to the army under a single system. Beginning in 1955 the leaders of the kwans began discussing in earnest the possibility of creating a unified Korean martial art. Until then, Tang Soo Do was the term used to for Korean Karate, using the Korean hanja pronunciation of the Japanese kanji (唐手道). The name Tae Soo Do (跆手道) was also used to describe a unified style Korean martial arts.[citation needed] This name consists of the hanja 跆 tae «to stomp, trample», 手 su «hand» and 道 do «way, discipline».

Choi Hong-hi advocated the use of the name Tae Kwon Do, replacing su «hand» with 拳 kwon (Revised Romanization: gwon; McCune–Reischauer: kkwŏn) «fist», the term also used for «martial arts» in Chinese (pinyin quán).[16] The name was also the closest to the pronunciation of Taekkyeon,[17] in accordance with the views of the president.[13][18] The new name was initially slow to catch on among the leaders of the kwans. During this time Taekwondo was also adopted for use by the South Korean military, which increased its popularity among civilian martial arts schools.[10][13]

In 1959 the Korea Taekwondo Association or KTA (then-Korea Tang Soo Do Association) was established to facilitate the unification of Korean martial arts. General Choi, of the Oh Do Kwan, wanted all the other member kwans of the KTA to adopt his own Chan Hon-style of Taekwondo, as a unified style. This was, however, met with resistance as the other kwans instead wanted a unified style to be created based on inputs from all the kwans, to serve as a way to bring on the heritage and characteristics of all of the styles, not just the style of a single kwan.[10] As a response to this, along with political disagreements about teaching Taekwondo in North Korea and unifying the whole Korean Peninsula, Choi broke with the (South Korea) KTA in 1966, in order to establish the International Taekwon-Do Federation (ITF)— a separate governing body devoted to institutionalizing his Chan Hon-style of Taekwondo in Canada.[10][13]