Иврит — многогранен и необычен, как и сам еврейский народ. Этот язык невероятно красив! Чтобы это понять, достаточно просто углубиться в историю названий, которые еще в прошлые века евреи давали городам, странам и частям света.

Каждый израильский город имеет свою неповторимую историю, которая начинается с его названия.

Тель-Авив — תל אביב. Значение названия этого города благородное и изящное — «Холм Весны».

Иерусалим — ירושלים — Иерушала́им. С древнееврейского это слово переводится как «Город мира».

Беэр-Шева — באר שבע. Перевод с иврита — «Колодец семи».

Хайфа — חיפה — Ха́йфа или Хэйфа́. В переводе на русский — «Берег».

Петах-Тиква — פתח תקווה. Название одного из крупнейших израильских городов означает «Врата надежды».

Ришон-ле-Цион — ראשון לציון. Название этого города взято из Книги пророка Исайи и переводится как «Первый — Сиону».

Бат-Ям — בַּת יָם. С иврита Бат-Ям переводится как «Дочь моря».

Рамат-Ган — רמת גן — на русский переводится как «Садовая возвышенность». Изначально город назывался Ир-Ганим (עיר גנים), что означает «Город садов».

Название города Бейт-Шемеш (בית שמש) на русском звучит так — «Дом Солнца».

Расположенный в Тель-Авивском округе город Гиватаим тоже имеет интересное название. С иврита — גִּבְעָתַיִם — это слово переводится как «Два холма».

А как же называются планеты на иврите?

Начнем с того, что у каждой планеты есть свое еврейское название. Эти названия не были придуманы кем-то конкретным. Все они взяты из Талмуда, Сефер Йецира и древнейших астрономических трактатов. К слову, «планета» на иврите звучит так — «кохАв лЕхэт» (כּוכָב לֶכֶת). Переводится это слово как «подвижная звезда».

Марс — מַאֲדִים — Маадим. Происходит от слова «адом» — красный.

Венера — נוֹגַה — Ногах. Переводится как «свечение».

Юпитер — צֶדֶק — Цедек. В русском переводе — «справедливый»

Сатурн — שַבְּתַאי — Шабтай. Один из переводов — «субботняя планета».

Меркурий — כּוכָב חַמָה — Хама. Перевод — «горячая».

Уран — אוֹרוֹן — Орон. Это слово означает «слабый свет».

Нептун — רַהַב — Рахав. Есть много версий значения такого названия. Например, в Танахе упоминается морское чудовище, имя которого Рахав.

Земля — כַּדוּר הָאָרֶץ — Кадур Хаарец. На русском звучит как «земной шар».

Части света на иврите

Северная Америка — אמריקה הצפונית

Южная Америка — אמריקה הדרומית

Европа — אירופה

Азия — אסיה

Африка — אפריקה

Австралия — אוסטרליה

Антарктика — אנטרקטיקה

Страны на иврите

אוקראינה — Украйна — Украина

רוסיה — Ру́сия — Россия

בלארוס — Беларус — Беларусь

תורכיה — Ту́ркия — Турция

סין — Син — Китай

יפן — Япан — Япония

הודו — ɦо́ду — Индия

לבנון — Лəвано́н — Ливан

סוריה — Су́рия — Сирия

לוב — Лув — Ливия

תוניסיה — Тунисия — Тунис

קפריסין — Кафрисин — Кипр

יון — Йаўа́н / Ява́н — Греция

רומניה — Рома́ния — Румыния

הונגריה — ɦунга́рия — Венгрия

ספרד — Сефара́д — Испания

צרפת — Сарəфа́ѳ / Царфат — Франция

פולין — Полин — Польша

ליטא — Ли́та — Литва

שבדיה — Шведия — Швеция

תורכיה — Ту́ркия — Турция

ארמניה — Армения — Армения

Подписаться на Telegram

|

Tel Aviv-Yafo תל־אביב-יפו (Hebrew) |

|

|---|---|

|

City |

|

|

From upper left: HaShalom interchange, Azrieli Sarona Tower, Jaffa Clock Tower, Tel Aviv Promenade and beach, panorama of the city |

|

|

Flag Coat of arms Brandmark |

|

Nicknames:

|

|

|

Tel Aviv-Yafo Location within Israel Tel Aviv-Yafo Location within Asia Tel Aviv-Yafo Location on Earth |

|

| Coordinates: 32°05′N 34°47′E / 32.08°N 34.78°ECoordinates: 32°05′N 34°47′E / 32.08°N 34.78°E | |

| Country | |

| District | |

| Metropolitan area | Gush Dan |

| Founded | 11 April 1909 |

| Named for | Tel Abib in Ezekiel 3:15, via Herzl’s Altneuland |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality |

| • Mayor | Ron Huldai |

| Area | |

| • City | 52 km2 (20 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 176 km2 (68 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 1,516 km2 (585 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 5 m (16 ft) |

| Population

(2021)[1] |

|

| • City | 467,875 |

| • Rank | 2nd in Israel |

| • Density | 8,468.7/km2 (21,934/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 12th in Israel |

| • Urban | 1,388,400 |

| • Urban density | 8,057.7/km2 (20,869/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,854,000 |

| • Metro density | 2,286/km2 (5,920/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Tel Avivian[2][3][4] |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (IST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (IDT) |

| Postal code |

61XXXXX |

| Area code | +972-3 |

| ISO 3166 code | IL-TA |

| GDP | US$ 153.3 billion[5] |

| GDP per capita | US$42,614[5] |

| Website | tel-aviv.gov.il |

|

UNESCO World Heritage Site |

|

| Official name | White City of Tel Aviv |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iv |

| Designated | 2003 |

| Reference no. | [1] |

| Region | Israel |

Tel Aviv-Yafo (Hebrew: תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, romanized: Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō [tel aˈviv ˈjafo]; Arabic: تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, romanized: Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the Gush Dan metropolitan area of Israel. Located on the Israeli Mediterranean coastline and with a population of 467,875, it is the economic and technological center of the country. If East Jerusalem is considered part of Israel, Tel Aviv is the country’s second most populous city after Jerusalem; if not, Tel Aviv is the most populous city ahead of West Jerusalem.[a]

Tel Aviv is governed by the Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality, headed by Mayor Ron Huldai, and is home to most of Israel’s foreign embassies.[b] It is a beta+ world city and is ranked 57th in the 2022 Global Financial Centres Index. Tel Aviv has the third- or fourth-largest economy and the largest economy per capita in the Middle East.[9][10] The city currently has the highest cost of living in the world.[11][12] Tel Aviv receives over 2.5 million international visitors annually.[13][14] A «party capital» in the Middle East, it has a lively nightlife and 24-hour culture.[15][16] The city is gay-friendly, with a large LGBT community.[17] Tel Aviv has been called «The World’s Vegan Food Capital», as it possesses the highest per capita population of vegans in the world, with many vegan eateries throughout the city.[18] Tel Aviv is home to Tel Aviv University, the largest university in the country with more than 30,000 students.

The city was founded in 1909 by the Yishuv (Jewish residents) as a modern housing estate on the outskirts of the ancient port city of Jaffa (Yafo in Hebrew), then part of the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem within the Ottoman Empire. It was at first called Ahuzat Bayit (lit. «House Estate» or «Homestead»),[19][20] the name of the association which established the neighbourhood. Its name was changed the following year to Tel Aviv, after the biblical name Tel Abib (lit. «Tell of Spring») adopted by Nahum Sokolow as the title for his Hebrew translation of Theodor Herzl’s 1902 novel Altneuland («Old New Land»). Other Jewish suburbs of Jaffa had been established before Tel Aviv, the oldest among them being Neve Tzedek.[21] Tel Aviv was given township status within the Jaffa Municipality in 1921, and became independent from Jaffa in 1934.[22][23]

Immigration by mostly Jewish refugees meant that the growth of Tel Aviv soon outpaced that of Jaffa, which had a majority Arab population at the time.[24] In 1948 the Israeli Declaration of Independence was proclaimed in the city. After the 1947–1949 Palestine war, Tel Aviv began the municipal annexation of parts of Jaffa, fully unified with Jaffa under the name Tel Aviv in April 1950, and was formally renamed to Tel Aviv-Yafo in August 1950.[25]

Tel Aviv’s White City, designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003, comprises the world’s largest concentration of International Style buildings, including Bauhaus and other related modernist architectural styles.[26][27] Popular attractions include Jaffa Old City, the Eretz Israel Museum, the Museum of Art, Hayarkon Park, and the city’s promenade and beach.

Etymology and origins

Tel Aviv is named after Theodor Herzl’s 1902 novel, Altneuland («Old New Land»), for which the title of the Hebrew translation by Nahum Sokolow was «Tel Aviv»

Tel Aviv is the Hebrew title of Theodor Herzl’s Altneuland («Old New Land»), translated from German by Nahum Sokolow. Sokolow had adopted the name of a Mesopotamian site near the city of Babylon mentioned in Ezekiel: «Then I came to them of the captivity at Tel Abib [Tel Aviv], that lived by the river Chebar, and to where they lived; and I sat there overwhelmed among them seven days.»[28] The name was chosen in 1910 from several suggestions, including «Herzliya». It was found fitting as it embraced the idea of a renaissance in the ancient Jewish homeland. Aviv (אביב, or Abib) is a Hebrew word that can be translated as «spring», symbolizing renewal, and tell (or tel) is an artificial mound created over centuries through the accumulation of successive layers of civilization built one over the other and symbolizing the ancient.

Although founded in 1909 as a small settlement on the sand dunes north of Jaffa, Tel Aviv was envisaged as a future city from the start. Its founders hoped that in contrast to what they perceived as the squalid and unsanitary conditions of neighbouring Arab towns, Tel Aviv was to be a clean and modern city, inspired by the European cities of Warsaw and Odessa.[29] The marketing pamphlets advocating for its establishment stated:[29]

In this city we will build the streets so they have roads and sidewalks and electric lights. Every house will have water from wells that will flow through pipes as in every modern European city, and also sewerage pipes will be installed for the health of the city and its residents.

— Akiva Arieh Weiss, 1906

History

Jaffa

The walled city of Jaffa was the only urban centre in the general area where now Tel Aviv is located in early modern times. Jaffa was an important port city in the region for millennia. Archaeological evidence shows signs of human settlement there starting in roughly 7,500 BC.[31] The city was established around 1,800 BC at the latest. Its natural harbour has been used since the Bronze Age. By the time Tel Aviv was founded as a separate city during Ottoman rule of the region, Jaffa had been ruled by the Canaanites, Egyptians, Philistines, Israelites, Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Phoenicians, Ptolemies, Seleucids, Hasmoneans, Romans, Byzantines, the early Islamic caliphates, Crusaders, Ayyubids, and Mamluks before coming under Ottoman rule in 1515. It had been fought over numerous times. The city is mentioned in ancient Egyptian documents, as well as the Hebrew Bible.

Other ancient sites in Tel Aviv include: Tell Qasile, Tel Gerisa, Abattoir Hill, Tel Hashash, and Tell Qudadi.

During the First Aliyah in the 1880s, when Jewish immigrants began arriving in the region in significant numbers, new neighborhoods were founded outside Jaffa on the current territory of Tel Aviv. The first was Neve Tzedek, founded in 1887 by Mizrahi Jews due to overcrowding in Jaffa and built on lands owned by Aharon Chelouche.[21] Other neighborhoods were Neve Shalom (1890), Yafa Nof (1896), Achva (1899), Ohel Moshe (1904), Kerem HaTeimanim (1906), and others. Once Tel Aviv received city status in the 1920s, those neighborhoods joined the newly formed municipality, now becoming separated from Jaffa.

1904–1917: Foundation in the Late Ottoman Period

Lottery for the first lots, April 1909

Nahlat Binyamin, 1913

The Second Aliyah led to further expansion. In 1906, a group of Jews, among them residents of Jaffa, followed the initiative of Akiva Aryeh Weiss and banded together to form the Ahuzat Bayit (lit. «homestead») society. One of the society’s goals was to form a «Hebrew urban centre in a healthy environment, planned according to the rules of aesthetics and modern hygiene.»[32] The urban planning for the new city was influenced by the garden city movement.[33] The first 60 plots were purchased in Kerem Djebali near Jaffa by Jacobus Kann, a Dutch citizen, who registered them in his name to circumvent the Turkish prohibition on Jewish land acquisition.[34] Meir Dizengoff, later Tel Aviv’s first mayor, also joined the Ahuzat Bayit society.[35][36] His vision for Tel Aviv involved peaceful co-existence with Arabs.[37][unreliable source][unreliable source]

On 11 April 1909, 66 Jewish families gathered on a desolate sand dune to parcel out the land by lottery using seashells. This gathering is considered the official date of the establishment of Tel Aviv. The lottery was organised by Akiva Aryeh Weiss, president of the building society.[38][39] Weiss collected 120 sea shells on the beach, half of them white and half of them grey. The members’ names were written on the white shells and the plot numbers on the grey shells. A boy drew names from one box of shells and a girl drew plot numbers from the second box. A photographer, Abraham Soskin, documented the event. The first water well was later dug at this site, located on what is today Rothschild Boulevard, across from Dizengoff House.[40] Within a year, Herzl, Ahad Ha’am, Yehuda Halevi, Lilienblum, and Rothschild streets were built; a water system was installed; and 66 houses (including some on six subdivided plots) were completed.[33] At the end of Herzl Street, a plot was allocated for a new building for the Herzliya Hebrew High School, founded in Jaffa in 1906.[33] The cornerstone for the building was laid on 28 July 1909. The town was originally named Ahuzat Bayit. On 21 May 1910, the name Tel Aviv was adopted.[33] The flag and city arms of Tel Aviv (see above) contain under the red Star of David 2 words from the biblical book of Jeremiah: «I (God) will build You up again and you will be rebuilt.» (Jer 31:4) Tel Aviv was planned as an independent Hebrew city with wide streets and boulevards, running water for each house, and street lights.[41]

By 1914, Tel Aviv had grown to more than 1 km2 (247 acres).[33] In 1915 a census of Tel Aviv was conducted, recording a population 2,679.[42] However, growth halted in 1917 when the Ottoman authorities expelled the residents of Jaffa and Tel Aviv as a wartime measure.[33] A report published in The New York Times by United States Consul Garrels in Alexandria, Egypt described the Jaffa deportation of early April 1917. The orders of evacuation were aimed chiefly at the Jewish population.[43] Jews were free to return to their homes in Tel Aviv at the end of the following year when, with the end of World War I and the defeat of the Ottomans, the British took control of Palestine.

The town had rapidly become an attraction to immigrants, with a local activist writing:[44]

The immigrants were attracted to Tel Aviv because they found in it all the comforts they were used to in Europe: electric light, water, a little cleanliness, cinema, opera, theatre, and also more or less advanced schools… busy streets, full restaurants, cafes open until 2 a.m., singing, music, and dancing.

British administration 1917–34: Townships within the Jaffa Municipality

1930 Survey of Palestine map, showing urban boundaries of Jaffa (green) and the Tel Aviv township (blue) within the Jaffa Municipality (red)[22][23]

Master plan for the Tel Aviv township, 1925

A master plan for the Tel Aviv township was created by Patrick Geddes, 1925, based on the garden city movement.[45] The plan consisted of four main features: a hierarchical system of streets laid out in a grid, large blocks consisting of small-scale domestic dwellings, the organization of these blocks around central open spaces, and the concentration of cultural institutions to form a civic center.[46]

Tel Aviv, along with the rest of the Jaffa municipality, was conquered by the British imperial army in late 1917 during the Sinai and Palestine Campaign of World War I and became part of British-administered Mandatory Palestine until 1948.

Tel Aviv, established as suburb of Jaffa, received «township» or local council status within the Jaffa Municipality in 1921.[47][22][23] According to a census conducted in 1922 by the British Mandate authorities, the Tel Aviv township had a population of 15,185 inhabitants, consisting of 15,065 Jews, 78 Muslims and 42 Christians.[48]

Increasing in the 1931 census to 46,101, in 12,545 houses.[49]

With increasing Jewish immigration during the British administration, friction between Arabs and Jews in Palestine increased. On 1 May 1921, the Jaffa riots resulted in the deaths of 48 Arabs and 47 Jews and injuries to 146 Jews and 73 Arabs.[50] In the wake of this violence, many Jews left Jaffa for Tel Aviv. The population of Tel Aviv increased from 2,000 in 1920 to around 34,000 by 1925.[26][51]

Tel Aviv began to develop as a commercial center.[52] In 1923, Tel Aviv was the first town to be wired to electricity in Palestine, followed by Jaffa later in the same year. The opening ceremony of the Jaffa Electric Company powerhouse, on 10 June 1923, celebrated the lighting of the two main streets of Tel Aviv.[53]

In 1925, the Scottish biologist, sociologist, philanthropist and pioneering town planner Patrick Geddes drew up a master plan for Tel Aviv which was adopted by the city council led by Meir Dizengoff. Geddes’s plan for developing the northern part of the district was based on Ebenezer Howard’s garden city movement.[45] While most of the northern area of Tel Aviv was built according to this plan, the influx of European refugees in the 1930s necessitated the construction of taller apartment buildings on a larger footprint in the city.[54]

Ben Gurion House was built in 1930–31, part of a new workers’ housing development. At the same time, Jewish cultural life was given a boost by the establishment of the Ohel Theatre and the decision of Habima Theatre to make Tel Aviv its permanent base in 1931.[33]

1934 municipal independence from Jaffa

Tel Aviv bus station during the Mandate era

Magen David Square in 1936

Tel Aviv was granted the status of an independent municipality separate from Jaffa in 1934.[22][23]

The Jewish population rose dramatically during the Fifth Aliyah after the Nazis came to power in Germany.[33] By 1937 the Jewish population of Tel Aviv had risen to 150,000, compared to Jaffa’s mainly Arab 69,000 residents. Within two years, it had reached 160,000, which was over a third of Palestine’s total Jewish population.[33] Many new Jewish immigrants to Palestine disembarked in Jaffa, and remained in Tel Aviv, turning the city into a center of urban life. Friction during the 1936–39 Arab revolt led to the opening of a local Jewish port, Tel Aviv Port, independent of Jaffa, in 1938. It closed on 25 October 1965. Lydda Airport (later Ben Gurion Airport) and Sde Dov Airport opened between 1937 and 1938.[55]

Many German Jewish architects trained at the Bauhaus, the Modernist school of architecture in Germany, and left Germany during the 1930s. Some, like Arieh Sharon, came to Palestine and adapted the architectural outlook of the Bauhaus and similar schools to the local conditions there, creating what is recognized as the largest concentration of buildings in the International Style in the world.[26]

Tel Aviv’s White City emerged in the 1930s, and became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2003.[56] During World War II, Tel Aviv was hit by Italian airstrikes on 9 September 1940, which killed 137 people in the city.[57]

During the Jewish insurgency in Mandatory Palestine, Jewish Irgun and Lehi guerrillas launched repeated attacks against British military, police, and government targets in the city. In 1946, following the King David Hotel bombing, the British carried out Operation Shark, in which the entire city was searched for Jewish militants and most of the residents questioned, during which the entire city was placed under curfew. During the March 1947 martial law in Mandatory Palestine, Tel Aviv was placed under martial law by the British authorities for 15 days, with the residents kept under curfew for all but three hours a day as British forces scoured the city for militants. In spite of this, Jewish guerrilla attacks continued in Tel Aviv and other areas under martial law in Palestine.

According to the 1947 UN Partition Plan for dividing Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, Tel Aviv, by then a city of 230,000, was to be included in the proposed Jewish state. Jaffa with, as of 1945, a population of 101,580 people—53,930 Muslims, 30,820 Jews and 16,800 Christians—was designated as part of the Arab state. Civil War broke out in the country and in particular between the neighbouring cities of Tel Aviv and Jaffa, which had been assigned to the Jewish and Arab states respectively. After several months of siege, on 13 May 1948, Jaffa fell and the Arab population fled en masse.

-

Tel Aviv 1943 1:20,000

-

Tel Aviv 1945 1:250,000

-

Tel Aviv, Allenby Street, 1940

-

Tel Aviv port 1939

-

State of Israel

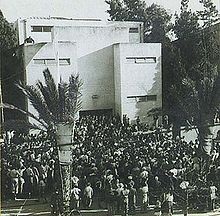

Crowd outside Dizengoff House (now Independence Hall) to witness the proclamation and signing of Israel’s Declaration of Independence in 1948

Independence

When Israel declared Independence on 14 May 1948, the population of Tel Aviv was over 200,000.[citation needed] Tel Aviv was the temporary government center of the State of Israel until the government moved to Jerusalem in December 1949. Due to the international dispute over the status of Jerusalem, most embassies remained in or near Tel Aviv.[58]

Growth in the 1950s and 1960s

The boundaries of Tel Aviv and Jaffa became a matter of contention between the Tel Aviv municipality and the Israeli government in 1948.[25] The former wished to incorporate only the northern Jewish suburbs of Jaffa, while the latter wanted a more complete unification.[25] The issue also had international sensitivity, since the main part of Jaffa was in the Arab portion of the United Nations Partition Plan, whereas Tel Aviv was not, and no armistice agreements had yet been signed.[25] On 10 December 1948, the government announced the annexation to Tel Aviv of Jaffa’s Jewish suburbs, the Palestinian neighborhood of Abu Kabir, the Arab village of Salama and some of its agricultural land, and the Jewish Hatikva slum.[25] On 25 February 1949, the depopulated Palestinian village of al-Shaykh Muwannis was also annexed to Tel Aviv.[25] On 18 May 1949, Manshiya and part of Jaffa’s central zone were added, for the first time including land that had been in the Arab portion of the UN partition plan.[25] The government voted on the unification of Tel Aviv and Jaffa on 4 October 1949, but the decision was not implemented until 24 April 1950 due to the opposition of Tel Aviv mayor Israel Rokach.[25] The name of the unified city was Tel Aviv until 19 August 1950, when it was renamed Tel Aviv-Yafo in order to preserve the historical name Jaffa.[25]

Tel Aviv thus grew to 42 km2 (16.2 sq mi). In 1949, a memorial to the 60 founders of Tel Aviv was constructed.[59]

In the 1960s, some of the older buildings were demolished, making way for the country’s first high-rises. The historic Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium was controversially demolished, to make way for the Shalom Meir Tower, which was completed in 1965, and remained Israel’s tallest building until 1999. Tel Aviv’s population peaked in the early 1960s at 390,000, representing 16 percent of the country’s total.[60]

1970s and 1980s population and urban decline

Azrieli Sarona tower (238.5 metres high), finished in 2017

Arlozorov Young Towers 1, finished in 2020

By the early 1970s, Tel Aviv had entered a long and steady period of continuous population decline, which was accompanied by urban decay. By 1981, Tel Aviv had entered not just natural population decline, but an absolute population decline as well.[61] In the late 1980s the city had an aging population of 317,000.[60] Construction activity had moved away from the inner ring of Tel Aviv, and had moved to its outer perimeter and adjoining cities. A mass out-migration of residents from Tel Aviv, to adjoining cities like Petah Tikva and Rehovot, where better housing conditions were available, was underway by the beginning of the 1970s, and only accelerated by the Yom Kippur War.[61] Cramped housing conditions and high property prices pushed families out of Tel Aviv and deterred young people from moving in.[60] From the beginning of 1970s, the common image of Tel Aviv became that of a decaying city,[62] as Tel Aviv’s population fell 20%.[63]

In the 1970s, the apparent sense of Tel Aviv’s urban decline became a theme in the work of novelists such as Yaakov Shabtai, in works describing the city such as Sof Davar (The End of Things) and Zikhron Devarim (The Memory of Things).[62] A symptomatic article of 1980 asked «Is Tel Aviv Dying?» and portrayed what it saw as the city’s existential problems: «Residents leaving the city, businesses penetrating into residential areas, economic and social gaps, deteriorating neighbourhoods, contaminated air – Is the First Hebrew City destined for a slow death? Will it become a ghost town?».[62] However, others saw this as a transitional period. By the late 1980s, attitudes to the city’s future had become markedly more optimistic. It had also become a center of nightlife and discotheques for Israelis who lived in the suburbs and adjoining cities. By 1989, Tel Aviv had acquired the nickname «Nonstop City», as a reflection of the growing recognition of its nightlife and 24/7 culture, and «Nonstop City» had to some extent replaced the former moniker of «First Hebrew City».[64]

The largest project built in this era was the Dizengoff Center, Israel’s first shopping mall, which was completed in 1983. Other notable projects included the construction of Marganit Tower in 1987, the opening of the Suzanne Dellal Center for Dance and Theater in 1989, and the Tel Aviv Cinematheque (opened in 1973 and located to the current building in 1989).

In the early 1980s, 13 embassies in Jerusalem moved to Tel Aviv as part of the UN’s measures responding to Israel’s 1980 Jerusalem Law.[65] Today, most national embassies are located in Tel Aviv or environs.[66]

1990s to present

In the 1990s, the decline in Tel Aviv’s population began to be reversed and stabilized, at first temporarily due to a wave of immigrants from the former Soviet Union.[60] Tel Aviv absorbed 42,000 immigrants from the FSU, many educated in scientific, technological, medical and mathematical fields.[63] In this period, the number of engineers in the city doubled.[67] Tel Aviv soon began to emerge as a global high-tech center.[37] The construction of many skyscrapers and high-tech office buildings followed. In 1993, Tel Aviv was categorized as a world city.[68]

However, the city’s municipality struggled to cope with an influx of new immigrants. Tel Aviv’s tax base had been shrinking for many years, as a result of its preceding long term population decline, and this meant there was little money available at the time to invest in the city’s deteriorating infrastructure and housing. In 1998, Tel Aviv was on the «verge of bankruptcy».[69] Economic difficulties would then be compounded by a wave of Palestinian suicide bombings in the city from the mid-1990s, to the end of the Second Intifada, as well as the dot-com bubble, which affected the city’s rapidly growing hi-tech sector.

On 4 November 1995, Israel’s prime minister, Yitzhak Rabin, was assassinated at a rally in Tel Aviv in support of the Oslo peace accord. The outdoor plaza where this occurred, formerly known as Kikar Malchei Yisrael, was renamed Rabin Square.[70]

New laws were introduced to protect Modernist buildings, and efforts to preserve them were aided by UNESCO recognition of Tel Aviv’s White City as a world heritage site in 2003. In the early 2000s, Tel Aviv municipality focused on attracting more young residents to the city. It made significant investment in major boulevards, to create attractive pedestrian corridors. Former industrial areas like the city’s previously derelict Northern Tel Aviv Port and the Jaffa railway station, were upgraded and transformed into leisure areas. A process of gentrification began in some of the poor neighborhoods of southern Tel Aviv and many older buildings began to be renovated.[37]

The demographic profile of the city changed in the 2000s, as it began to attract a higher proportion of young residents. By 2012, 28 percent of the city’s population was aged between 20 and 34 years old. Between 2007 and 2012, the city’s population growth averaged 6.29 percent. As a result of its population recovery and industrial transition, the city’s finances were transformed, and by 2012 it was running a budget surplus and maintained a credit rating of AAA+.[71]

In the 2000s and early 2010s, Tel Aviv received tens of thousands of illegal immigrants, primarily from Sudan and Eritrea,[72] changing the demographic profile of areas of the city.

In 2009, Tel Aviv celebrated its official centennial.[73] In addition to city- and country-wide celebrations, digital collections of historical materials were assembled. These include the History section of the official Tel Aviv-Yafo Centennial Year website;[73] the Ahuzat Bayit collection, which focuses on the founding families of Tel Aviv, and includes photographs and biographies;[74] and Stanford University’s Eliasaf Robinson Tel Aviv Collection,[75] documenting the history of the city. Today, the city is regarded as a strong candidate for global city status.[76] Over the past 60 years, Tel Aviv had developed into a secular, liberal-minded center with a vibrant nightlife and café culture.[37]

Arab–Israeli conflict

In the Gulf War in 1991, Tel Aviv was attacked by Scud missiles from Iraq. Iraq hoped to provoke an Israeli military response, which could have destroyed the US–Arab alliance. The United States pressured Israel not to retaliate, and after Israel acquiesced, the US and Netherlands rushed Patriot missiles to defend against the attacks, but they proved largely ineffective. Tel Aviv and other Israeli cities continued to be hit by Scuds throughout the war, and every city in the Tel Aviv area except for Bnei Brak was hit. A total of 74 Israelis died as a result of the Iraqi attacks, mostly from suffocation and heart attacks,[77] while approximately 230 Israelis were injured.[78] Extensive property damage was also caused, and some 4,000 Israelis were left homeless. It was feared that Iraq would fire missiles filled with nerve agents or sarin. As a result, the Israeli government issued gas masks to its citizens. When the first Iraqi missiles hit Israel, some people injected themselves with an antidote for nerve gas. The inhabitants of the southeastern suburb of Hatikva erected an angel-monument as a sign of their gratitude that «it was through a great miracle, that many people were preserved from being killed by a direct hit of a Scud rocket.»[79]

Since the First Intifada, Tel Aviv has suffered from Palestinian political violence. The first suicide attack in Tel Aviv occurred on 19 October 1994, on the Line 5 bus, when a bomber killed 22 civilians and injured 50 as part of a Hamas suicide campaign.[80] On 6 March 1996, another Hamas suicide bomber killed 13 people (12 civilians and 1 soldier), many of them children, in the Dizengoff Center suicide bombing.[81][82] Three women were killed by a Hamas terrorist in the Café Apropo bombing on 27 March 1997.[83][84][85]

One of the deadliest attacks occurred on 1 June 2001, during the Second Intifada, when a suicide bomber exploded at the entrance to the Dolphinarium discothèque, killing 21, mostly teenagers, and injuring 132.[86][87][88][89] Another Hamas suicide bomber killed six civilians and injured 70 in the Allenby Street bus bombing.[90][91][92][93][94] Twenty-three civilians were killed and over 100 injured in the Tel Aviv central bus station massacre.[95][96] Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades claimed responsibility for the attack. In the Mike’s Place suicide bombing, an attack on a bar by a British Muslim suicide bomber resulted in the deaths of three civilians and wounded over 50.[97] Hamas and Al Aqsa Martyrs Brigades claimed joint responsibility. An Islamic Jihad bomber killed five and wounded over 50 on 25 February 2005 Stage Club bombing.[98] The most recent suicide attack in the city occurred on 17 April 2006, when 11 people were killed and at least 70 wounded in a suicide bombing near the old central bus station.[99]

Another attack took place on 29 August 2011 in which a Palestinian attacker stole an Israeli taxi cab and rammed it into a police checkpoint guarding the popular Haoman 17 nightclub in Tel Aviv which was filled with 2,000[100] Israeli teenagers. After crashing, the assailant went on a stabbing spree, injuring eight people.[98] Due to an Israel Border Police roadblock at the entrance and immediate response of the Border Police team during the subsequent stabbings, a much larger and fatal mass-casualty incident was avoided.[101]

On 21 November 2012, during Operation Pillar of Defense, the Tel Aviv area was targeted by rockets, and air raid sirens were sounded in the city for the first time since the Gulf War. All of the rockets either missed populated areas or were shot down by an Iron Dome rocket defense battery stationed near the city. During the operation, a bomb blast on a bus wounded at least 28 civilians, three seriously.[102][103][104][105] This was described as a terrorist attack by Israel, Russia, and the United States and was condemned by the United Nations, United States, United Kingdom, France and Russia, whilst Hamas spokesman Sami Abu Zuhri declared that the organisation «blesses» the attack.[106]

More than 300 rockets were fired towards the Tel Aviv Metropolitan area in the 2021 Israel–Palestine crisis.[107]

Geography

Tel Aviv seen from space in 2003

City plan of Tel Aviv, Israel

Tel Aviv is located around 32°5′N 34°48′E / 32.083°N 34.800°E on the Israeli Mediterranean coastline, in central Israel, the historic land bridge between Europe, Asia and Africa. Immediately north of the ancient port of Jaffa, Tel Aviv lies on land that used to be sand dunes and as such has relatively poor soil fertility. The land has been flattened and has no important gradients; its most notable geographical features are bluffs above the Mediterranean coastline and the Yarkon River mouth.[108] Because of the expansion of Tel Aviv and the Gush Dan region, absolute borders between Tel Aviv and Jaffa and between the city’s neighborhoods do not exist.

The city is located 60 km (37 mi) northwest of Jerusalem and 90 km (56 mi) south of the city of Haifa.[109] Neighboring cities and towns include Herzliya to the north, Ramat HaSharon to the northeast, Petah Tikva, Bnei Brak, Ramat Gan and Giv’atayim to the east, Holon to the southeast, and Bat Yam to the south.[110] The city is economically stratified between the north and south. Southern Tel Aviv is considered less affluent than northern Tel Aviv with the exception of Neve Tzedek and northern and north-western Jaffa. Central Tel Aviv is home to Azrieli Center and the important financial and commerce district along Ayalon Highway. The northern side of Tel Aviv is home to Tel Aviv University, Hayarkon Park, and upscale residential neighborhoods such as Ramat Aviv and Afeka.[111]

Climate

Tel Aviv has a Mediterranean climate (Köppen climate classification: Csa),[112] and enjoys plenty of sunshine throughout the year. Most precipitation falls in the form of rain between the months of October and April, with intervening dry summers. The average annual temperature is 20.9 °C (69.6 °F), and the average sea temperature is 18–20 °C (64–68 °F) during the winter, and 24–29 °C (75–84 °F) during the summer. The city averages 528 mm (20.8 in) of precipitation annually.

Summers in Tel Aviv last about five months, from June to October. August, the warmest month, averages a high of 30.6 °C (87.1 °F), and a low of 25 °C (77 °F). The high relative humidity due to the location of the city by the Mediterranean Sea, in a combination with the high temperatures, creates a thermal discomfort during the summer. Summer low temperatures in Tel Aviv seldom drop below 20 °C (68 °F).

Winters are mild and wet, with most of the annual precipitation falling within the months of December, January and February as intense rainfall and thunderstorms. In January, the coolest month, the average maximum temperature is 17.6 °C (63.7 °F), the minimum temperature averages 10.2 °C (50.4 °F). During the coldest days of winter, temperatures may vary between 8 °C (46 °F) and 12 °C (54 °F). Both freezing temperatures and snowfall are extremely rare in the city.

Autumns and springs are characterized by sharp temperature changes, with heat waves that might be created due to hot and dry air masses that arrive from the nearby deserts. During heatwaves in autumn and springs, temperatures usually climb up to 35 °C (95 °F) and even up to 40 °C (104 °F), accompanied with exceptionally low humidity. An average day during autumn and spring has a high of 23 °C (73 °F) to 25 °C (77 °F), and a low of 15 °C (59 °F) to 18 °C (64 °F).

The highest recorded temperature in Tel Aviv was 46.5 °C (115.7 °F) on 17 May 1916, and the lowest is −1.9 °C (28.6 °F) on 7 February 1950, during a cold wave that brought the only recorded snowfall in Tel Aviv.

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18.8 (65.8) |

17.6 (63.7) |

17.9 (64.2) |

18.6 (65.5) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.9 (76.8) |

27.4 (81.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.2 (82.8) |

26.3 (79.3) |

23.2 (73.8) |

20.6 (69.1) |

| Climate data for Tel Aviv (Temperature: 1987–2010, Precipitation: 1980–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.0 (86.0) |

33.2 (91.8) |

38.3 (100.9) |

43.9 (111.0) |

46.5 (115.7) |

44.4 (111.9) |

37.4 (99.3) |

41.4 (106.5) |

42.0 (107.6) |

44.4 (111.9) |

35.6 (96.1) |

33.5 (92.3) |

46.5 (115.7) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 23.6 (74.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

30.4 (86.7) |

35.5 (95.9) |

32.4 (90.3) |

30.8 (87.4) |

31.6 (88.9) |

31.8 (89.2) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.9 (91.2) |

29.2 (84.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

35.5 (95.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 17.5 (63.5) |

17.7 (63.9) |

19.2 (66.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

24.9 (76.8) |

27.5 (81.5) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.4 (84.9) |

27.3 (81.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

19.2 (66.6) |

24.0 (75.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.9 (55.2) |

13.4 (56.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.2 (66.6) |

21.8 (71.2) |

24.8 (76.6) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.8 (82.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

22.7 (72.9) |

17.6 (63.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

20.3 (68.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9.6 (49.3) |

9.8 (49.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.3 (63.1) |

20.6 (69.1) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.7 (74.7) |

22.5 (72.5) |

19.1 (66.4) |

14.6 (58.3) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.4 (61.6) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 6.6 (43.9) |

7.3 (45.1) |

8.3 (46.9) |

10.7 (51.3) |

14.0 (57.2) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

23.3 (73.9) |

20.6 (69.1) |

16.2 (61.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

6.6 (43.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 147 (5.8) |

111 (4.4) |

62 (2.4) |

16 (0.6) |

4 (0.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

1 (0.0) |

34 (1.3) |

81 (3.2) |

127 (5.0) |

583 (22.9) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 15 | 13 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 71 |

| Average relative humidity (%) (at 1200 GMT) | 72 | 70 | 65 | 60 | 63 | 67 | 70 | 67 | 60 | 65 | 68 | 73 | 67 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 192.2 | 200.1 | 235.6 | 270.0 | 328.6 | 357.0 | 368.9 | 356.5 | 300.0 | 279.0 | 234.0 | 189.1 | 3,311 |

| Source 1: Israel Meteorological Service[114][115][116][117] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Hong Kong Observatory for data of sunshine hours[118] |

| Climate data for Tel Aviv the West Coast (2005–2014) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 27.7 (81.9) |

31.8 (89.2) |

38.3 (100.9) |

39.1 (102.4) |

38.4 (101.1) |

36.7 (98.1) |

31.7 (89.1) |

32.5 (90.5) |

34.1 (93.4) |

39.5 (103.1) |

34.0 (93.2) |

29.5 (85.1) |

39.5 (103.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 18.3 (64.9) |

18.9 (66.0) |

20.7 (69.3) |

22.6 (72.7) |

24.4 (75.9) |

27.1 (80.8) |

29.0 (84.2) |

29.9 (85.8) |

29.0 (84.2) |

26.9 (80.4) |

23.9 (75.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

24.3 (75.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.7 (58.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

17.2 (63.0) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

26.9 (80.4) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.5 (79.7) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 11.1 (52.0) |

11.9 (53.4) |

13.6 (56.5) |

16.0 (60.8) |

18.9 (66.0) |

22.4 (72.3) |

24.7 (76.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.7 (69.3) |

16.5 (61.7) |

12.8 (55.0) |

18.2 (64.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

7.2 (45.0) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.6 (70.9) |

22.5 (72.5) |

20.1 (68.2) |

15.1 (59.2) |

10.2 (50.4) |

4.0 (39.2) |

4.0 (39.2) |

| Source: Israel Meteorological Service databases[119][120] |

Local government

Tel Aviv is governed by a 31-member city council elected for a five-year term by in direct proportional elections,[121] and a mayor elected for the same term by direct elections under a two-round system. Like all other mayors in Israel, no term limits exist for the Mayor of Tel Aviv.[122] All Israeli citizens over the age of 17 with at least one year of residence in Tel Aviv are eligible to vote in municipal elections. The municipality is responsible for social services, community programs, public infrastructure, urban planning, tourism and other local affairs.[123][124][125] The Tel Aviv City Hall is located at Rabin Square. Ron Huldai has been mayor of Tel Aviv since 1998.[121] Huldai was reelected for a fifth term in the 2018 municipal elections, defeating former deputy Asaf Zamir, founder of the Ha’Ir party.[126] Huldai’s has become the longest-serving mayor of the city, exceeding Shlomo Lahat’s 19-year term.[126] The shortest-serving was David Bloch, in office for two years, 1925–27.

Politically, Tel Aviv is known to be a stronghold for the left, in both local and national issues. The left wing vote is especially prevalent in the city’s mostly affluent central and northern neighborhoods, though not the case for its working-class southeastern neighborhoods which tend to vote for right wing parties in national elections.[127] Outside the kibbutzim, Meretz receives more votes in Tel Aviv than in any other city in Israel.[128]

List of Mayors of Tel Aviv

Mandatory Palestine (1920–1948)

| Mayor of Tel Aviv | Took office | Left office | Party | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

Meir Dizengoff | 1920 | 1925 | General Zionists |

| 2 |

|

David Bloch-Blumenfeld | 1925 | 1928 | Ahdut HaAvoda |

| (1) |

|

Meir Dizengoff | 1928 | 1936 | General Zionists |

| 3 |

|

Moshe Chelouche | 1936 | 1936 | Unaffiliated |

| 4 |

|

Israel Rokach | 1936 | 1948 | General Zionists |

State of Israel (1948–present)

| Mayor of Tel Aviv | Took office | Left office | Party | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (4) |

|

Israel Rokach | 1948 | 1953 | General Zionists |

| 5 |

|

Chaim Levanon | 1953 | 1959 | General Zionists |

| 6 | Mordechai Namir | 1959 | 1969 | Mapai | |

| 7 |

|

Yehoshua Rabinovitz | 1969 | 1974 | Labor Party |

| 8 |

|

Shlomo Lahat | 1974 | 1993 | Likud |

| 9 |

|

Roni Milo | 1993 | 1998 | Likud |

| 10 |

|

Ron Huldai | 1998 | Incumbent | Labor Party |

City council

Education

In 2006, 51,359 children attended school in Tel Aviv, of whom 8,977 were in municipal kindergartens, 23,573 in municipal elementary schools, and 18,809 in high schools.[129] Sixty-four percent of students in the city are entitled to matriculation, more than 5 percent higher than the national average.[129] About 4,000 children are in first grade at schools in the city, and population growth is expected to raise this number to 6,000.[130] As a result, 20 additional kindergarten classes were opened in 2008–09 in the city. A new elementary school is planned north of Sde Dov as well as a new high school in northern Tel Aviv.[130]

The first Hebrew high school, called Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium, was established in Jaffa in 1905 and moved to Tel Aviv after its founding in 1909, where a new campus on Herzl Street was constructed for it.

Tel Aviv University, the largest university in Israel, is known internationally for its physics, computer science, chemistry and linguistics departments. Together with Bar-Ilan University in neighboring Ramat Gan, the student population numbers over 50,000, including a sizeable international community.[131][132] Its campus is located in the neighborhood of Ramat Aviv.[133] Tel Aviv also has several colleges.[134]

The Herzliya Hebrew Gymnasium moved from Jaffa to old Tel Aviv in 1909 and moved to Jabotinsky Street in the early 1960s.[135] Other notable schools in Tel Aviv include Shevah Mofet, the second Hebrew school in the city, Ironi Alef High School for Arts and Alliance.

Demographics

Sarona, old Templer houses and modern highrises

Tel Aviv has a population of 467,875 spread over a land area of 52,000 dunams (52 km2; 20 sq mi),[1] yielding a population density of 7,606 people per square km (19,699 per square mile). According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), as of 2009 Tel Aviv’s population is growing at an annual rate of 0.5 percent. Jews of all backgrounds form 91.8 percent of the population, Muslims and Arab Christians make up 4.2 percent, and the remainder belong to other groups (including various Christian and Asian communities).[136] As Tel Aviv is a multicultural city, many languages are spoken in addition to Hebrew. According to some estimates, about 50,000 unregistered African and Asian foreign workers live in the city.[137] Compared with Westernised cities, crime in Tel Aviv is relatively low.[138]

According to Tel Aviv-Yafo Municipality, the average income in the city, which has an Unemployment Rate of 4.6%,[139] is 20% above the national average.[129] The city’s education standards are above the national average: of its 12th-grade students, 64.4 percent are eligible for matriculation certificates.[129] The age profile is relatively even, with 22.2 percent aged under 20, 18.5 percent aged 20–29, 24 percent aged 30–44, 16.2 percent aged between 45 and 59, and 19.1 percent older than 60.[140]

Tel Aviv’s population reached a peak in the early 1960s at around 390,000, falling to 317,000 in the late 1980s as high property prices forced families out and deterred young couples from moving in.[60] Since the 1990s, population has steadily grown.[60] Today, the city’s population is young and growing.[130] In 2006, 22,000 people moved to the city, while only 18,500 left,[130] and many of the new families had young children. The population is expected to reach 535,000 in 2030;[141] meanwhile, the average age of residents fell from 35.8 in 1983 to 34 in 2008.[130] The population over age 65 stands at 14.6 percent compared with 19% in 1983.[130]

Religion

Tel Aviv has 544 active synagogues,[142] including historic buildings such as the Great Synagogue, established in the 1930s.[143] In 2008, a center for secular Jewish studies and a secular yeshiva opened in the city.[144] Tensions between religious and secular Jews before the 2006 gay pride parade ended in vandalism of a synagogue.[145] The number of churches has grown to accommodate the religious needs of diplomats and foreign workers.[146] In 2019, the population was 89.9% Jewish, and 4.5% Arabs; among Arabs 82.8% were Muslims, 16.4% were Christians, and 0.8% were Druze.[147] The remaining 5 percent were not classified by religion. Israel Meir Lau is Chief Rabbi of the city.[148]

Tel Aviv is an ethnically diverse city. The Jewish population, which forms the majority group in Tel Aviv, consists of the descendants of immigrants from all parts of the world, including Ashkenazi Jews from Europe, North America, South America, Australia and South Africa, as well as Sephardic and Mizrahi Jews from Southern Europe, North Africa, India, Central Asia, West Asia, and the Arabian Peninsula. There are also a sizable number of Ethiopian Jews and their descendants living in Tel Aviv. In addition to Muslim and Arab Christian minorities in the city, several hundred Armenian Christians who reside in the city are concentrated mainly in Jaffa and some Christians from the former Soviet Union who immigrated to Israel with Jewish spouses and relatives. In recent years, Tel Aviv has received many non-Jewish migrants from Asia and Africa, students, foreign workers (documented and undocumented) and refugees. There are many economic migrants and refugees from African countries, primarily Eritrea and Sudan, located in the southern part of the city.[149]

Neighborhoods

Tel Aviv is divided into nine districts that have formed naturally over the city’s short history. The oldest of these is Jaffa, the ancient port city out of which Tel Aviv grew. This area is traditionally made up demographically of a greater percentage of Arabs, but recent gentrification is replacing them with a young professional and artist population. Similar processes are occurring in nearby Neve Tzedek, the original Jewish neighborhood outside of Jaffa. Ramat Aviv, a district in the northern part of the city that is largely made up of luxury apartments and includes Tel Aviv University, is currently undergoing extensive expansion and is set to absorb the beachfront property of Sde Dov Airport after its decommissioning.[150] The area known as HaKirya is the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) headquarters and a large military base.[111] Moreover, in the past few years, Rothschild Boulevard which is beginning in Neve Tzedek has become an attraction for tourists, businesses and startups. It features a wide, tree-lined central strip with pedestrian and bike lanes. Historically, there was a demographic split between the Ashkenazi northern side of the city, including the district of Ramat Aviv, and the southern, more Sephardi and Mizrahi neighborhoods including Neve Tzedek and Florentin.[37][unreliable source]

Since the 1980s, major restoration and gentrification projects have been implemented in southern Tel Aviv.[37][unreliable source] Baruch Yoscovitz, city planner for Tel Aviv beginning in 2001, reworked old British plans for the Florentin neighborhood from the 1920s, adding green areas, pedestrian malls, and housing. The municipality invested two million shekels in the project. The goal was to make Florentin the Soho of Tel Aviv, and attract artists and young professionals to the neighborhood. Indeed, street artists, such as Dede, installation artists such as Sigalit Landau, and many others made the upbeat neighborhood their home base.[151][152] Florentin is now known as a hip, «cool» place to be in Tel Aviv with coffeehouses, markets, bars, galleries and parties.[153]

Cityscape

Architecture

Tel Aviv is home to different architectural styles that represent influential periods in its history. The early architecture of Tel Aviv consisted largely of European-style single-storey houses with red-tiled roofs.[154] Neve Tzedek, the first neighbourhood to be built outside of Jaffa, is characterised by two-storey sandstone buildings.[26] By the 1920s, a new eclectic Orientalist style came into vogue, combining European architecture with Eastern features such as arches, domes and ornamental tiles.[154] Municipal construction followed the «garden city» master plan drawn up by Patrick Geddes. Two- and three-storey buildings were interspersed with boulevards and public parks.[154] Various architectural styles, such as Art Deco, classical and modernist also exist in Tel Aviv.

International Style and Bauhaus

Bauhaus architecture was introduced in the 1920s and 1930s by German Jewish architects who settled in Palestine after the rise of the Nazis. Tel Aviv’s White City, around the city center, contains more than 5,000 Modernist-style buildings inspired by the Bauhaus school and Le Corbusier.[26][27] Construction of these buildings, later declared protected landmarks and, collectively, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, continued until the 1950s in the area around Rothschild Boulevard.[27][155] Some 3,000 buildings were created in this style between 1931 and 1939 alone.[154] In the 1960s, this architectural style gave way to office towers and a chain of waterfront hotels and commercial skyscrapers.[37] Some of the city’s Modernist buildings were neglected to the point of ruin. Before legislation to preserve this landmark architecture, many of the old buildings were demolished. Efforts are under way to refurbish Bauhaus buildings and restore them to their original condition.[156]

High-rise construction and towers

The Azrieli Center complex contains some of the tallest skyscrapers in Tel Aviv

The Shalom Meir Tower, Israel’s first skyscraper, was built in Tel Aviv in 1965 and remained the country’s tallest building until 1999. At the time of its construction, the building rivaled Europe’s tallest buildings in height, and was the tallest in the Middle East.

In the mid-1990s, the construction of skyscrapers began throughout the entire city, altering its skyline. Before that, Tel Aviv had had a generally low-rise skyline.[157] However, the towers were not concentrated in certain areas, and were scattered at random locations throughout the city, creating a disjointed skyline.

New neighborhoods, such as Park Tzameret, have been constructed to house apartment towers such as Yoo Tel Aviv towers, designed by Philippe Starck. Other districts, such as Sarona, have been developed with office towers. Other recent additions to Tel Aviv’s skyline include the 1 Rothschild Tower and First International Bank Tower.[158][159] As Tel Aviv celebrated its centennial in 2009,[160] the city attracted a number of architects and developers, including I. M. Pei, Donald Trump, and Richard Meier.[161] American journalist David Kaufman reported in New York magazine that since Tel Aviv «was named a UNESCO World Heritage site, gorgeous historic buildings from the Ottoman and Bauhaus era have been repurposed as fabulous hotels, eateries, boutiques, and design museums.»[162] In November 2009, Haaretz reported that Tel Aviv had 59 skyscrapers more than 100 meters tall.[163] Currently, dozens of skyscrapers have been approved or are under construction throughout the city, and many more are planned. The tallest building approved is the Egged Tower, which would become Israel’s tallest building upon completion.[164] According to current plans, the tower is planned to have 80 floors, rise to a height of 270 meters, and will have a 50-meter spire.[165]

In 2010, the Tel Aviv Municipality’s Planning and Construction Committee launched a new master plan for the city for 2025. It decided not to allow the construction of any additional skyscrapers in the city center, while at the same time greatly increasing the construction of skyscrapers in the east. The ban extends to an area between the coast and Ibn Gabirol Street, and also between the Yarkon River and Eilat Street. It did not extend to towers already under construction or approved. One final proposed skyscraper project was approved, while dozens of others had to be scrapped. Any new buildings there will usually not be allowed to rise above six and a half stories. However, hotel towers along almost the entire beachfront will be allowed to rise up to 25 stories. According to the plan, large numbers of skyscrapers and high-rise buildings at least 18 stories tall would be built in the entire area between Ibn Gabirol Street and the eastern city limits, as part of the master plan’s goal of doubling the city’s office space to cement Tel Aviv as the business capital of Israel. Under the plan, «forests» of corporate skyscrapers will line both sides of the Ayalon Highway. Further south, skyscrapers rising up to 40 stories will be built along the old Ottoman railway between Neve Tzedek and Florentine, with the first such tower there being the Neve Tzedek Tower. Along nearby Shlavim Street, passing between Jaffa and south Tel Aviv, office buildings up to 25 stories will line both sides of the street, which will be widened to accommodate traffic from the city’s southern entrance to the center.[166][167]

In November 2012, it was announced that to encourage investment in the city’s architecture, residential towers throughout Tel Aviv would be extended in height. Buildings in Jaffa and the southern and eastern districts may have two and a half stories added, while those on Ibn Gabirol Street might be extended by seven and a half stories.[168]

Economy

Tel Aviv has been ranked as the twenty-fifth most important financial center in the world.[169] In 1926, the country’s first shopping arcade, Passage Pensak, was built there.[170] By 1936, as tens of thousands of middle class immigrants arrived from Europe, Tel Aviv was already the largest city in Palestine. A small port was built at the Yarkon estuary, and many cafes, clubs and cinemas opened. Herzl Street became a commercial thoroughfare at this time.[171]

Economic activities account for 17 percent of the GDP.[60] In 2011, Tel Aviv had an unemployment rate of 4.4 percent.[172] The city has been described as a «flourishing technological center» by Newsweek and a «miniature Los Angeles» by The Economist.[173][174] In 1998, the city was described by Newsweek as one of the 10 most technologically influential cities in the world. Since then, high-tech industry in the Tel Aviv area has continued to develop.[174] The Tel Aviv metropolitan area (including satellite cities such as Herzliya and Petah Tikva) is Israel’s center of high-tech, sometimes referred to as Silicon Wadi.[174][175]

Tel Aviv is home to the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange (TASE), Israel’s only stock exchange, which has reached record heights since the 1990s.[176] The Tel Aviv Stock exchange has also gained attention for its resilience and ability to recover from war and disasters. For example, the Tel Aviv Stock Exchange was higher on the last day of both the 2006 Lebanon war and the 2009 Operation in Gaza than on the first day of fighting.[177] Many international venture-capital firms, scientific research institutes and high-tech companies are headquartered in the city. Industries in Tel Aviv include chemical processing, textile plants and food manufacturers.[37][unreliable source]

In 2016, the Globalization and World Cities Study Group and Network (GaWC) at Loughborough University reissued an inventory of world cities based on their level of advanced producer services. Tel Aviv was ranked as an alpha- world city.[178]

The Kiryat Atidim high tech zone opened in 1972 and the city has become a major world high tech hub. In December 2012, the city was ranked second on a list of top places to found a high tech startup company, just behind Silicon Valley.[179] In 2013, Tel Aviv had more than 700 startup companies and research and development centers, and was ranked the second-most innovative city in the world, behind Medellín and ahead of New York City.[180]

According to Forbes, nine of its fifteen Israeli-born billionaires live in Israel; four live in Tel Aviv and its suburbs.[181][182] The cost of living in Israel is high, with Tel Aviv being its most expensive city to live in. In 2021, Tel Aviv became the world’s most expensive city to live in, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit.[183][11]

Shopping malls in Tel Aviv include Dizengoff Center, Ramat Aviv Mall and Azrieli Shopping Mall and markets such as Carmel Market, Ha’Tikva Market, and Bezalel Market.

Culture and contemporary life

Entertainment and performing arts

Tel Aviv is a major center of culture and entertainment.[184] Eighteen of Israel’s 35 major centers for the performing arts are located in the city, including five of the country’s nine large theatres, where 55% of all performances in the country and 75 percent of all attendance occurs.[60][185] The Tel Aviv Performing Arts Center is home of the Israeli Opera, where Plácido Domingo was house tenor between 1962 and 1965, and the Cameri Theatre.[186] With 2,482 seats, the Heichal HaTarbut is the city’s largest theatre and home to the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra.[187]

Habima Theatre, Israel’s national theatre, was closed down for renovations in early 2008, and reopened in November 2011 after major remodeling. Enav Cultural Center is one of the newer additions to the cultural scene.[185] Other theatres in Tel Aviv are the Gesher Theatre and Beit Lessin Theater; Tzavta and Tmuna are smaller theatres that host musical performances and fringe productions. In Jaffa, the Simta and Notzar theatres specialize in fringe as well. Tel Aviv is home to the Batsheva Dance Company, a world-famous contemporary dance troupe. The Israeli Ballet is also based in Tel Aviv.[185] Tel Aviv’s center for modern and classical dance is the Suzanne Dellal Center for Dance and Theatre in Neve Tzedek.[188]

The city often hosts international musicians at venues such as Hayarkon Park, Expo Tel Aviv, the Barby Club, the Zappa Club and Live Park Rishon Lezion just south of Tel Aviv.[189][190][191] The city hosted the Eurovision Song Contest 2019 (the first Israeli-hosted Eurovision held outside of Jerusalem), following Israel’s win the year prior.[192] Opera and classical music performances are held daily in Tel Aviv, with many of the world’s leading classical conductors and soloists performing on Tel Aviv stages over the years.[185]

The Tel Aviv Cinematheque screens art movies, premieres of short and full-length Israeli films, and hosts a variety of film festivals, among them the Festival of Animation, Comics and Caricatures, «Icon» Science Fiction and Fantasy Festival, the Student Film Festival, the Jazz, Film and Videotape Festival and Salute to Israeli Cinema. The city has several multiplex cinemas.[185]

Tourism and recreation

Tel Aviv receives about 2.5 million international visitors annually, the fifth-most-visited city in the Middle East & Africa.[13][14] In 2010, Knight Frank‘s world city survey ranked it 34th globally.[193] Tel Aviv has been named the third «hottest city for 2011» (behind only New York City and Tangier) by Lonely Planet, third-best in the Middle East and Africa by Travel + Leisure magazine (behind only Cape Town and Jerusalem), and the ninth-best beach city in the world by National Geographic.[194][195][196] Tel Aviv is consistently ranked as one of the top LGBT destinations in the world.[197][198] The city has also been ranked as one of the top 10 oceanfront cities.[199]

Tel Aviv is known as «the city that never sleeps» and a «party capital» due to its thriving nightlife, young atmosphere and famous 24-hour culture.[15][16][200] Tel Aviv has branches of some of the world’s leading hotels, including the Crowne Plaza, Sheraton, Dan, Isrotel and Hilton. It is home to many museums, architectural and cultural sites, with city tours available in different languages.[201] Apart from bus tours, architectural tours, Segway tours, and walking tours are also popular.[202][203][204] Tel Aviv has 44 hotels with more than 6,500 rooms.[129]

The beaches of Tel Aviv and the city’s promenade play a major role in the city’s cultural and touristic scene, often ranked as some of the best beaches in the world.[196] Hayarkon Park is the most visited urban park in Israel, with 16 million visitors annually. Other parks within city limits include Charles Clore Park, Independence Park, Meir Park and Dubnow Park. About 19% of the city land are green spaces.[205]

-

Hayarkon Park is the largest city park in Tel Aviv

-

Early evening at the beach

Nightlife

Tel Aviv is an international hub of highly active and diverse nightlife with bars, dance bars and nightclubs staying open well past midnight. The largest area for nightclubs is the Tel Aviv port, where the city’s large, commercial clubs and bars draw big crowds of young clubbers from both Tel Aviv and neighboring cities. The South of Tel Aviv is known for the popular Haoman 17 club, as well as for being the city’s main hub of alternative clubbing, with underground venues including established clubs like the Block Club, Comfort 13 and Paradise Garage, as well as various warehouse and loft party venues. The Allenby/Rothschild area is another popular nightlife hub, featuring such clubs as the Pasaz, Radio EPGB and the Penguin. In 2013, Absolut Vodka introduced a specially designed bottle dedicated to Tel Aviv as part of its international cities series.[206]

Fashion

Tel Aviv has become an international center of fashion and design.[207] It has been called the «next hot destination» for fashion.[citation needed] Israeli designers, such as swimwear company Gottex show their collections at leading fashion shows, including New York’s Bryant Park fashion show.[citation needed] In 2011, Tel Aviv hosted its first fashion week since the 1980s, with Italian designer Roberto Cavalli as a guest of honor.[208]

LGBT culture

Named «the best gay city in the world» by American Airlines, Tel Aviv is one of the most popular destinations for LGBT tourists internationally, with a large LGBT community.[209][17] Approximately 25% of Tel Aviv’s population identify as gay.[210][211] American journalist David Kaufman has described the city as a place «packed with the kind of ‘we’re here, we’re queer’ vibe more typically found in Sydney and San Francisco. The city hosts its well-known pride parade, the biggest in Asia, attracting over 200,000 people yearly.[212]

In January 2008, Tel Aviv’s municipality established the city’s LGBT Community center, providing all of the municipal and cultural services to the LGBT community under one roof. In December 2008, Tel Aviv began putting together a team of gay athletes for the 2009 World Outgames in Copenhagen.[213] In addition, Tel Aviv hosts an annual LGBT film festival, known as TLVFest.

Tel Aviv’s LGBT community is the subject of Eytan Fox’s 2006 film The Bubble.

Cuisine

Tel Aviv is famous for its wide variety of world-class restaurants, offering traditional Israeli dishes as well as international fare.[214] More than 100 sushi restaurants, the third highest concentration in the world, do business in the city.[215]

In Tel Aviv there are some dessert specialties, the most known is the Halva ice cream traditionally topped with date syrup and pistachios.

Museums

Israel has the highest number of museums per capita of any country, with three of the largest located in Tel Aviv.[216][217] Among these are the Eretz Israel Museum, known for its collection of archaeology and history exhibits dealing with the Land of Israel, and the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. Housed on the campus of Tel Aviv University is Beit Hatfutsot, a museum of the international Jewish diaspora that tells the story of Jewish prosperity and persecution throughout the centuries of exile. Batey Haosef Museum specializes in Israel Defense Forces military history. The Palmach Museum near Tel Aviv University offers a multimedia experience of the history of the Palmach. Right next to Charles Clore Park is a museum of the Irgun. The Israel Trade Fairs & Convention Center, located in the northern part of the city, hosts more than 60 major events annually. Many offbeat museums and galleries operate in the southern areas, including the Tel Aviv Raw Art contemporary art gallery.[218][219]

Sports

Maccabi Tel Aviv Sports Club was founded in 1906 and competes in more than 10 sport fields. Its basketball team, Maccabi Tel Aviv Basketball Club, is a world-known professional team, that holds 55 Israeli titles, has won 45 editions of the Israel cup, and has six European Championships, and its football team Maccabi Tel Aviv Football Club has won 23 Israeli league titles and has won 24 State Cups, seven Toto Cups and two Asian Club Championships. Yael Arad, an athlete in Maccabi’s judo club, won a silver medal in the 1992 Olympic Games.[220]

Hapoel Tel Aviv Sports Club, founded in 1923, comprises more than 11 sports clubs,[221] including Hapoel Tel Aviv Football Club (13 championships, 16 State Cups, one Toto Cup and once Asian champions) which plays in Bloomfield Stadium, and Hapoel Tel Aviv Basketball Club.

Bnei Yehuda Tel Aviv (once Israeli champion, twice State Cup winners and twice Toto Cup winner) is the Israeli football team that represents a neighborhood, the Hatikva Quarter in Tel Aviv, and not a city.

Beitar Tel Aviv Bat Yam formerly played in the top division, the club now playing in Liga Leumit and also represents the city Bat Yam.

Maccabi Jaffa formerly played in the top division, the club now playing in Liga Alef and represents the Jaffa.

Shimshon Tel Aviv formerly played in the top division, the club now playing in Liga Alef.

There are more Tel Aviv football teams: Hapoel Kfar Shalem, F.C. Bnei Jaffa Ortodoxim, Beitar Ezra, Beitar Jaffa, Elitzur Jaffa Tel Aviv, F.C. Roei Heshbon Tel Aviv, Gadna Tel Aviv Yehuda, Hapoel Kiryat Shalom, Hapoel Neve Golan and Hapoel Ramat Yisrael.

The city has a number of football stadiums, the largest of which is Bloomfield Stadium, which contains 29,400 seats used by Hapoel Tel Aviv, Maccabi Tel Aviv and Bnei Yehuda. Another stadium in the city is the Hatikva Neighborhood Stadium.

Menora Mivtachim Arena is a large multi-purpose sports indoor arena, The arena is home to the Maccabi Tel Aviv, and the Drive in Arena, a multi-purpose hall that serves as the home ground of the Hapoel Tel Aviv.

National Sport Center Tel Aviv (also Hadar Yosef Sports Center) is a compound of stadiums and sports facilities. It also houses the Olympic Committee of Israel and the National Athletics Stadium with the Israeli Athletic Association.

Two rowing clubs operate in Tel Aviv. The Tel Aviv Rowing Club, established in 1935 on the banks of the Yarkon River, is the largest rowing club in Israel.[222] Meanwhile, the beaches of Tel Aviv provide a vibrant Matkot (beach paddleball) scene.[223] Tel Aviv Lightning represent Tel Aviv in the Israel Baseball League.[224] Tel Aviv also has an annual half marathon, run in 2008 by 10,000 athletes with runners coming from around the world.[225]

In 2009, the Tel Aviv Marathon was revived after a fifteen-year hiatus, and is run annually since, attracting a field of over 18,000 runners.[226]

Tel Aviv is also ranked to be 10th best to-skateboarding city by Transworld Skateboarding.

Media

The three largest newspaper companies in Israel: Yedioth Ahronoth, Maariv and Haaretz are all based within the city limits.[227] Several radio stations cover the Tel Aviv area, including the city-based Radio Tel Aviv.[228]

The two major Israeli television networks, Keshet Media Group and Reshet, are based in the city, as well as two of the most popular radio stations in Israel: Galatz and Galgalatz, which are both based in Jaffa. Studios of the international news channel i24news is located at Jaffa Port Customs House. An English language radio station, TLV1, is based at Kikar Hamedina.

Environment and urban restoration

IDF soldiers cleaning the beaches at Tel Aviv, which have scored highly in environmental tests[229]

Tel Aviv is ranked as the greenest city in Israel.[230] Since 2008, city lights are turned off annually in support of Earth Hour.[231] In February 2009, the municipality launched a water saving campaign, including competition granting free parking for a year to the household that is found to have consumed the least water per person.[232]

In the early 21st century, Tel Aviv’s municipality transformed a derelict power station into a public park, now named «Gan HaHashmal» («Electricity Park»), paving the way for eco-friendly and environmentally conscious designs.[233] In October 2008, Martin Weyl turned an old garbage dump near Ben Gurion International Airport, called Hiriya, into an attraction by building an arc of plastic bottles.[234] The site, which was renamed Ariel Sharon Park to honor Israel’s former prime minister, will serve as the centerpiece in what is to become a 2,000-acre (8.1 km2) urban wilderness on the outskirts of Tel Aviv, designed by German landscape architect, Peter Latz.[234]

At the end of the 20th century, the city began restoring historical neighborhoods such as Neve Tzedek and many buildings from the 1920s and 1930s. Since 2007, the city hosts its well-known, annual Open House Tel Aviv weekend, which offers the general public free entrance to the city’s famous landmarks, private houses and public buildings. In 2010, the design of the renovated Tel Aviv Port (Nemal Tel Aviv) won the award for outstanding landscape architecture at the European Biennial for Landscape Architecture in Barcelona.[235]

In 2014, the Sarona Market Complex opened, following an 8-year renovation project of Sarona colony.[236]

Transportation

Tel Aviv is a major transportation hub, served by a comprehensive public transport network, with many major routes of the national transportation network running through the city.

Bus and taxi

As with the rest of Israel, bus transport is the most common form of public transport and is very widely used. The Tel Aviv Central Bus Station is located in the southern part of the city. The main bus network in Tel Aviv metropolitan area operated by Dan Bus Company, Metropoline and Kavim. the Egged Bus Cooperative, Israels’s largest bus company, provides intercity transportation.[237]

The city is also served by local and inter-city share taxis. Many local and inter-city bus routes also have sherut taxis that follow the same route and display the same route number in their window. Fares are standardised within the region and are comparable to or less expensive than bus fares. Unlike other forms of public transport, these taxis also operate on Fridays and Saturdays (the Jewish sabbath «Shabbat»). Private taxis are white with a yellow sign on top. Fares are standardised and metered, but may be negotiated ahead of time with the driver.[238]

Rail

The Tel Aviv Savidor Central Railway Station is the main railway station of the city, and the second-busiest station in Israel. The city has five additional railway stations along the Ayalon Highway: three of them, Tel Aviv University, HaShalom (the busiest station in Israel, adjacent to Azrieli Center) and HaHagana (near the Tel Aviv Central Bus Station), serve Tel Aviv directly, while the remaining two, Holon Junction and Holon-Wolfson, are within Tel Aviv’s municipal boundaries but serve the southern suburb of Holon. It is estimated that over a million passengers travel by rail to Tel Aviv monthly. The trains do not run on Saturday and the principal Jewish festivals (Rosh Hashana (2 days), Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Simkhat Torah, Pessach (Passover) first and fifth days and Shavuot (Pentecost)).

Jaffa Railway Station was the first railway station in the Middle East. It served as the terminus for the Jaffa–Jerusalem railway. The station opened in 1891 and closed in 1948. In 2005–2009, the station was restored and converted into an entertainment and leisure venue marketed as «HaTachana», Hebrew for «the station» (see homepage here:[239]). The Jaffa–Jerusalem railway also included the Tel Aviv Beit Hadar railway station, which was opened in 1920 and replaced in 1970, and the Tel Aviv South railway station, which was opened in 1970 to replace Beit Hadar and itself closed in 1993. The Bnei Brak railway station, while located in Bnei Brak’s municipal borders, is closer to the Tel Aviv neighborhood of Ramat HaHayal than to Bnei Brak’s city center and was originally called Tel Aviv North.

Light rail

Tel Aviv Light Rail is a planned mass transit system for the Tel Aviv metropolitan area. As of 2021, three LRT lines are under construction. Work on the Red Line, the first in the project, started on September 21, 2011, following years of preparatory works,[240] and is expected to be completed in late 2022 after numerous delays.[241][242] Construction of the Purple Line started in December 2018;[243] work on the Green Line began in 2021 and is scheduled for completion in 2028.[244]

Metro

Tel Aviv Metro is a proposed subway system for the Tel Aviv Metropolitan Area. It will augment the Tel Aviv Light Rail and Israel Railways suburban lines and 3 underground metro lines to form a rapid transit transportation solution for the city. Construction is expected to start in 2025, with the first public opening in 2032.[245]

Roads