«Tenn» redirects here. For the Japanese MC, see Tenn (MC).

|

Tennessee ᏔᎾᏏ (Cherokee) |

|

|---|---|

|

State |

|

| State of Tennessee | |

|

Flag Seal |

|

| Nickname:

The Volunteer State[1] |

|

| Motto(s):

Agriculture and Commerce |

|

| Anthem: Nine songs | |

Map of the United States with Tennessee highlighted |

|

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Southwest Territory |

| Admitted to the Union | June 1, 1796; 226 years ago (16th) |

| Capital (and largest city) |

Nashville[2] |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Nashville |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Bill Lee (R) |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Randy McNally (R) |

| Legislature | General Assembly |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Tennessee Supreme Court |

| U.S. senators | Marsha Blackburn (R) Bill Hagerty (R) |

| U.S. House delegation | 8 Republicans 1 Democrat (list) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 42,143 sq mi (109,247 km2) |

| • Land | 41,217 sq mi (106,846 km2) |

| • Water | 926 sq mi (2,401 km2) 2.2% |

| • Rank | 36th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 440 mi (710 km) |

| • Width | 120 mi (195 km) |

| Elevation | 900 ft (270 m) |

| Highest elevation

(Clingmans Dome[3][a]) |

6,643 ft (2,025 m) |

| Lowest elevation

(Mississippi River at Mississippi border[3][a]) |

178 ft (54 m) |

| Population

(2020) |

|

| • Total | 6,916,897[4] |

| • Rank | 16th |

| • Density | 167.8/sq mi (64.8/km2) |

| • Rank | 20th |

| • Median household income | $54,833[5] |

| • Income rank | 42nd |

| Demonyms | Tennessean Big Bender (archaic) Volunteer (historical significance) |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English |

| • Spoken language | Language spoken at home[6]

|

| Time zones | |

| East Tennessee | UTC−05:00 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| Middle and West | UTC−06:00 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| USPS abbreviation |

TN |

| ISO 3166 code | US-TN |

| Traditional abbreviation | Tenn. |

| Latitude | 34°59′ N to 36°41′ N |

| Longitude | 81°39′ W to 90°19′ W |

| Website | www.tn.gov |

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

Flag of Tennessee |

|

Seal of Tennessee |

|

| Poem | «Oh Tennessee, My Tennessee» by William Lawrence |

| Slogan | «Tennessee—America at its best» |

| Living insignia | |

| Amphibian | Tennessee cave salamander |

| Bird | Northern mockingbird Bobwhite quail |

| Butterfly | Zebra swallowtail |

| Fish | Channel catfish Smallmouth bass |

| Flower | Iris Passion flower Tennessee echinacea |

| Insect | Firefly Lady beetle Honey bee |

| Mammal | Tennessee Walking Horse Raccoon |

| Reptile | Eastern box turtle |

| Tree | Tulip poplar Eastern red cedar |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Milk |

| Dance | Square dance |

| Firearm | Barrett M82 |

| Food | Tomato |

| Fossil | Pterotrigonia (Scabrotrigonia) thoracica |

| Gemstone | Tennessee River pearl |

| Mineral | Agate |

| Rock | Limestone |

| Tartan | Tennessee State Tartan |

| State route marker | |

|

|

| State quarter | |

Released in 2002 |

|

| Lists of United States state symbols |

Tennessee ( TEN-ih-SEE, TEN-iss-ee),[7][8][9] officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to the north, Virginia to the northeast, North Carolina to the east, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi to the south, Arkansas to the southwest, and Missouri to the northwest. Tennessee is geographically, culturally, and legally divided into three Grand Divisions of East, Middle, and West Tennessee. Nashville is the state’s capital and largest city, and anchors its largest metropolitan area. Other major cities include Memphis, Knoxville, Chattanooga, and Clarksville. Tennessee’s population as of the 2020 United States census is approximately 6.9 million.[10]

Tennessee is rooted in the Watauga Association, a 1772 frontier pact generally regarded as the first constitutional government west of the Appalachian Mountains.[11] Its name derives from «Tanasi», a Cherokee town in the eastern part of the state that existed before the first European American settlement.[12] Tennessee was initially part of North Carolina, and later the Southwest Territory, before its admission to the Union as the 16th state on June 1, 1796. It earned the nickname «The Volunteer State» early in its history due to a strong tradition of military service.[13] A slave state until the American Civil War, Tennessee was politically divided, with its western and middle parts supporting the Confederacy and the eastern region harboring pro-Union sentiment. As a result, Tennessee was the last state to secede and the first readmitted to the Union after the war.[14]

During the 20th century, Tennessee transitioned from a predominantly agrarian society to a more diversified economy. This was aided in part by massive federal investment in the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and the city of Oak Ridge, which was established during World War II to house the Manhattan Project’s uranium enrichment facilities for the construction of the world’s first atomic bombs. After the war, the Oak Ridge National Laboratory became a key center of scientific research. In 2016, the element tennessine was named for the state, largely in recognition of the roles played by Oak Ridge, Vanderbilt University, and the University of Tennessee in its discovery.[15] Tennessee has also played a major role in the development of many forms of popular music, including country, blues, rock and roll, soul, and gospel.

Tennessee has diverse terrain and landforms, and from east to west, contains a mix of cultural features characteristic of Appalachia, the Upland South, and the Deep South. The Blue Ridge Mountains along the eastern border reach some of the highest elevations in eastern North America, and the Cumberland Plateau contains many scenic valleys and waterfalls. The central part of the state is marked by cavernous bedrock and irregular rolling hills, and level, fertile plains define West Tennessee. The state is twice bisected by the Tennessee River, and the Mississippi River forms its western border. Its economy is dominated by the health care, music, finance, automotive, chemical, electronics, and tourism sectors, and cattle, soybeans, corn, poultry, and cotton are its primary agricultural products.[16] The Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the nation’s most visited national park, is in eastern Tennessee.[17]

Etymology[edit]

Tennessee derives its name most directly from the Cherokee town of Tanasi (or «Tanase», in syllabary: ᏔᎾᏏ) in present-day Monroe County, Tennessee, on the Tanasi River, now known as the Little Tennessee River. This town appeared on British maps as early as 1725. In 1567, Spanish explorer Captain Juan Pardo and his party encountered a Native American village named «Tanasqui» in the area while traveling inland from modern-day South Carolina; however, it is unknown if this was the same settlement as Tanasi.[b] Recent research suggests that the Cherokees adapted the name from the Yuchi word Tana-tsee-dgee, meaning «brother-waters-place» or «where-the-waters-meet».[19][20][21] The modern spelling, Tennessee, is attributed to Governor James Glen of South Carolina, who used this spelling in his official correspondence during the 1750s. In 1788, North Carolina created «Tennessee County», and in 1796, a constitutional convention, organizing the new state out of the Southwest Territory, adopted «Tennessee» as the state’s name.[22]

History[edit]

Pre-European era[edit]

The first inhabitants of Tennessee were Paleo-Indians who arrived about 12,000 years ago at the end of the Last Glacial Period. Archaeological excavations indicate that the lower Tennessee Valley was heavily populated by Ice Age hunter-gatherers, and Middle Tennessee is believed to have been rich with game animals such as mastodons.[23] The names of the cultural groups who inhabited the area before European contact are unknown, but archaeologists have named several distinct cultural phases, including the Archaic (8000–1000 BC), Woodland (1000 BC–1000 AD), and Mississippian (1000–1600 AD) periods.[24] The Archaic peoples first domesticated dogs, and plants such as squash, corn, gourds, and sunflowers were first grown in Tennessee during the Woodland period.[25] Later generations of Woodland peoples constructed the first mounds. Rapid civilizational development occurred during the Mississippian period, when Indigenous peoples developed organized chiefdoms and constructed numerous ceremonial structures throughout the state.[26]

Spanish conquistadors who explored the region in the 16th century encountered some of the Mississippian peoples, including the Muscogee Creek, Yuchi, and Shawnee.[27][28] By the early 18th century, most Natives in Tennessee had disappeared, most likely wiped out by diseases introduced by the Spaniards.[27] The Cherokee began migrating into what is now eastern Tennessee from what is now Virginia in the latter 17th century, possibly to escape expanding European settlement and diseases in the north.[29] They forced the Creek, Yuchi, and Shawnee out of the state in the early 18th century.[29][30] The Chickasaw remained confined to West Tennessee, and the middle part of the state contained few Native Americans, although both the Cherokee and the Shawnee claimed the region as their hunting ground.[31] Cherokee peoples in Tennessee were known by European settlers as the Overhill Cherokee because they lived west of the Blue Ridge Mountains.[32] Overhill settlements grew along the rivers in East Tennessee in the early 18th century.[33]

Exploration and colonization[edit]

The first recorded European expeditions into what is now Tennessee were led by Spanish explorers Hernando de Soto in 1540–1541, Tristan de Luna in 1559, and Juan Pardo in 1566–1567.[34][35][36] In 1673, English fur trader Abraham Wood sent an expedition from the Colony of Virginia into Overhill Cherokee territory in modern-day northeastern Tennessee.[37][38] That same year, a French expedition led by missionary Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet explored the Mississippi River and became the first Europeans to map the Mississippi Valley.[38][37] In 1682, an expedition led by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle constructed Fort Prudhomme on the Chickasaw Bluffs in West Tennessee.[39] By the late 17th century, French traders began to explore the Cumberland River valley, and in 1714, under Charles Charleville’s command, established French Lick, a fur trading settlement at the present location of Nashville near the Cumberland River.[40][41] In 1739, the French constructed Fort Assumption under Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville on the Mississippi River at the present location of Memphis, which they used as a base against the Chickasaw during the 1739 Campaign of the Chickasaw Wars.[42]

Reconstruction of Fort Loudoun, the first British settlement in Tennessee

In the 1750s and 1760s, longhunters from Virginia explored much of East and Middle Tennessee.[43] Settlers from the Colony of South Carolina built Fort Loudoun on the Little Tennessee River in 1756, the first British settlement in what is now Tennessee and the westernmost British outpost to that date.[44][45] Hostilities erupted between the British and the Cherokees into an armed conflict, and a siege of the fort ended with its surrender in 1760.[46] After the French and Indian War, Britain issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which forbade settlements west of the Appalachian Mountains in an effort to mitigate conflicts with the Natives.[47] But migration across the mountains continued, and the first permanent European settlers began arriving in northeastern Tennessee in the late 1760s.[48][49] Most of them were English, but nearly 20% were Scotch-Irish.[50] They formed the Watauga Association in 1772, a semi-autonomous representative government,[51] and three years later reorganized themselves into the Washington District to support the cause of the American Revolutionary War.[52] The next year, after an unsuccessful petition to Virginia, North Carolina agreed to annex the Washington District to provide protection from Native American attacks.[53]

In 1775, Richard Henderson negotiated a series of treaties with the Cherokee to sell the lands of the Watauga settlements at Sycamore Shoals on the banks of the Watauga River. An agreement to sell land for the Transylvania Colony, which included the territory in Tennessee north of the Cumberland River, was also signed.[54] Later that year, Daniel Boone, under Henderson’s employment, blazed a trail from Fort Chiswell in Virginia through the Cumberland Gap, which became part of the Wilderness Road, a major thoroughfare into Tennessee and Kentucky.[55] The Chickamauga, a Cherokee faction loyal to the British led by Dragging Canoe, opposed the settling of the Washington District and Transylvania Colony, and in 1776 attacked Fort Watauga at Sycamore Shoals.[56][57] The warnings of Dragging Canoe’s cousin Nancy Ward spared many settlers’ lives from the initial attacks.[58] In 1779, James Robertson and John Donelson led two groups of settlers from the Washington District to the French Lick.[59] These settlers constructed Fort Nashborough, which they named for Francis Nash, a brigadier general of the Continental Army.[60] The next year, the settlers signed the Cumberland Compact, which established a representative government for the colony called the Cumberland Association.[61] This settlement later grew into the city of Nashville.[62] That same year John Sevier led a group of Overmountain Men from Fort Watauga to the Battle of Kings Mountain in South Carolina, where they defeated the British.[63]

The Southwest Territory in 1790

Three counties of the Washington District broke off from North Carolina in 1784 and formed the State of Franklin.[64] Efforts to obtain admission to the Union failed, and the counties, now numbering eight, rejoined North Carolina by 1788.[65] North Carolina ceded the area to the federal government in 1790, after which it was organized into the Southwest Territory on May 26 of that year.[66] The act allowed the territory to petition for statehood once the population reached 60,000.[66] Administration of the territory was divided between the Washington District and the Mero District, the latter of which consisted of the Cumberland Association and was named for Spanish territorial governor Esteban Rodríguez Miró.[67] President George Washington appointed William Blount as territorial governor.[68] The Southwest Territory recorded a population of 35,691 in the first United States census that year, including 3,417 slaves.[69]

Statehood and antebellum era[edit]

As support for statehood grew among the settlers, Governor Blount called for elections, which were held in December 1793.[70] The 13-member territorial House of Representatives first convened in Knoxville on February 24, 1794, to select ten members for the legislature’s upper house, the council.[70] The full legislature convened on August 25, 1794.[71] In June 1795, the legislature conducted a census of the territory, which recorded a population of 77,263, including 10,613 slaves, and a poll that showed 6,504 in favor of statehood and 2,562 opposed.[72][73] Elections for a constitutional convention were held in December 1795, and the delegates convened in Knoxville on January 17, 1796, to begin drafting a state constitution.[74] During this convention, the name Tennessee was chosen for the new state.[22] The constitution was completed on February 6, which authorized elections for the state’s new legislature, the Tennessee General Assembly.[75][76] The legislature convened on March 28, 1796, and the next day, John Sevier was announced as the state’s first governor.[75][76] Tennessee was admitted to the Union on June 1, 1796, as the 16th state and the first created from federal territory.[77][78]

Tennessee reportedly earned the nickname «The Volunteer State» during the War of 1812, when 3,500 Tennesseans answered a recruitment call by the General Assembly for the war effort.[79] These soldiers, under Andrew Jackson’s command, played a major role in the American victory at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815, the last major battle of the war.[79] Several Tennesseans took part in the Texas Revolution of 1835–36, including Governor Sam Houston and Congressman and frontiersman Davy Crockett, who was killed at the Battle of the Alamo.[80] The state’s nickname was solidified during the Mexican–American War when President James K. Polk of Tennessee issued a call for 2,800 soldiers from the state, and more than 30,000 volunteered.[81]

Between the 1790s and 1820s, additional land cessions were negotiated with the Cherokee, who had established a national government modeled on the U.S. Constitution.[82][83] In 1818, Jackson and Kentucky governor Isaac Shelby reached an agreement with the Chickasaw to sell the land between the Mississippi and Tennessee Rivers to the United States, which included all of West Tennessee and became known as the «Jackson Purchase».[84] The Cherokee moved their capital from Georgia to the Red Clay Council Grounds in southeastern Tennessee in 1832, due to new laws forcing them from their previous capital at New Echota.[85] In 1838 and 1839, U.S. troops forcibly removed thousands of Cherokees and their black slaves from their homes in southeastern Tennessee and forced them to march to Indian Territory in modern-day Oklahoma. This event is known as the Trail of Tears, and an estimated 4,000 died along the way.[86][87]

As settlers pushed west of the Cumberland Plateau, a slavery-based agrarian economy took hold in these regions.[88] Cotton planters used extensive slave labor on large plantation complexes in West Tennessee’s fertile and flat terrain after the Jackson Purchase.[89] Cotton also took hold in the Nashville Basin during this time.[89] Entrepreneurs such as Montgomery Bell used slaves in the production of iron in the Western Highland Rim, and slaves also cultivated such crops as tobacco and corn throughout the Highland Rim.[88] East Tennessee’s geography did not allow for large plantations as in the middle and western parts of the state, and as a result, slavery became increasingly rare in the region.[90] A strong abolition movement developed in East Tennessee, beginning as early as 1797, and in 1819, Elihu Embree of Jonesborough began publishing the Manumission Intelligencier (later The Emancipator), the nation’s first exclusively anti-slavery newspaper.[91][92]

Civil War[edit]

At the onset of the American Civil War, most Middle and West Tennesseans favored efforts to preserve their slavery-based economies, but many Middle Tennesseans were initially skeptical of secession. In East Tennessee, most people favored remaining in the Union.[93] In 1860, slaves composed about 25% of Tennessee’s population, the lowest share among the states that joined the Confederacy.[94] Tennessee provided more Union troops than any other Confederate state, and the second-highest number of Confederate troops, behind Virginia.[95][14] Due to its central location, Tennessee was a crucial state during the war and saw more military engagements than any state except Virginia.[96]

After Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, secessionists in the state government led by Governor Isham Harris sought voter approval to sever ties with the United States, which was rejected in a referendum by a 54–46% margin in February 1861.[97] After the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter in April and Lincoln’s call for troops in response, the legislature ratified an agreement to enter a military league with the Confederacy on May 7, 1861.[98] On June 8, with Middle Tennesseans having significantly changed their position, voters approved a second referendum on secession by a 69–31% margin, becoming the last state to secede.[99] In response, East Tennessee Unionists organized a convention in Knoxville with the goal of splitting the region to form a new state loyal to the Union.[100] In the fall of 1861, Unionist guerrillas in East Tennessee burned bridges and attacked Confederate sympathizers, leading the Confederacy to invoke martial law in parts of the region.[101] In March 1862, Lincoln appointed native Tennessean and War Democrat Andrew Johnson as military governor of the state.[102]

General Ulysses S. Grant and the U.S. Navy captured the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers in February 1862 at the battles of Fort Henry and Fort Donelson.[103] Grant then proceeded south to Pittsburg Landing and held off a Confederate counterattack at Shiloh in April in what was at the time the bloodiest battle of the war.[104] Memphis fell to the Union in June after a naval battle on the Mississippi River.[105] Union strength in Middle Tennessee was tested in a series of Confederate offensives beginning in the summer of 1862, which culminated in General William Rosecrans’s Army of the Cumberland routing General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee at Stones River, another one of the war’s costliest engagements.[106] The next summer, Rosecrans’s Tullahoma campaign forced Bragg’s remaining troops in Middle Tennessee to retreat to Chattanooga with little fighting.[107]

During the Chattanooga campaign, Confederates attempted to besiege the Army of the Cumberland into surrendering, but reinforcements from the Army of the Tennessee under the command of Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and Joseph Hooker arrived.[108] The Confederates were driven from the city at the battles of Lookout Mountain and Missionary Ridge in November 1863.[109] Despite Unionist sentiment in East Tennessee, Confederates held the area for most of the war. A few days after the fall of Chattanooga, Confederates led by James Longstreet unsuccessfully campaigned to take control of Knoxville by attacking Union General Ambrose Burnside’s Fort Sanders.[110] The capture of Chattanooga allowed Sherman to launch the Atlanta campaign from the city in May 1864.[111] The last major battles in the state came when Army of Tennessee regiments under John Bell Hood invaded Middle Tennessee in the fall of 1864 in an effort to draw Sherman back. They were checked by John Schofield at Franklin in November and completely dispersed by George Thomas at Nashville in December.[112] On April 27, 1865, the worst maritime disaster in American history occurred when the Sultana steamboat, which was transporting freed Union prisoners, exploded in the Mississippi River north of Memphis, killing 1,168 people.[113]

When the Emancipation Proclamation was announced, Tennessee was largely held by Union forces and thus not among the states enumerated, so it freed no slaves there.[114] Andrew Johnson declared all slaves in Tennessee free on October 24, 1864.[114] On February 22, 1865, the legislature approved an amendment to the state constitution prohibiting slavery, which was approved by voters the following month, making Tennessee the only Southern state to abolish slavery.[115][116] Tennessee ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, which outlawed slavery in every state, on April 7, 1865,[117] and the Fourteenth Amendment, which granted citizenship and equal protection under the law to former slaves, on July 18, 1866.[118] Johnson became vice president when Lincoln was reelected, and president after Lincoln’s assassination in May 1865.[102] On July 24, 1866, Tennessee became the first Confederate state to have its elected members readmitted to Congress.[119]

Reconstruction and late 19th century[edit]

The years after the Civil War were characterized by tension and unrest between blacks and former Confederates, the worst of which occurred in Memphis in 1866.[120] Because Tennessee had ratified the Fourteenth Amendment before its readmission to the Union, it was the only former secessionist state that did not have a military governor during Reconstruction.[118] The Radical Republicans seized control of the state government toward the end of the war, and appointed William G. «Parson» Brownlow governor. Under Brownlow’s administration from 1865 to 1869, the legislature allowed African American men to vote, disenfranchised former Confederates, and took action against the Ku Klux Klan, which was founded in December 1865 in Pulaski as a vigilante group to advance former Confederates’ interests.[121] In 1870, Southern Democrats regained control of the state legislature,[122] and over the next two decades, passed Jim Crow laws to enforce racial segregation.[123]

Memphis became known as the «Cotton Capital of the World» in the years following the Civil War

A number of epidemics swept through Tennessee in the years after the Civil War, including cholera in 1873, which devastated the Nashville area,[124] and yellow fever in 1878, which killed more than one-tenth of Memphis’s residents.[125][126] Reformers worked to modernize Tennessee into a «New South» economy during this time. With the help of Northern investors, Chattanooga became one of the first industrialized cities in the South.[127] Memphis became known as the «Cotton Capital of the World» during the late 19th century, and Nashville, Knoxville, and several smaller cities saw modest industrialization.[127] Northerners also began exploiting the coalfields and mineral resources in the Appalachian Mountains. To pay off debts and alleviate overcrowded prisons, the state turned to convict leasing, providing prisoners to mining companies as strikebreakers, which was protested by miners forced to compete with the system.[128] An armed uprising in the Cumberland Mountains known as the Coal Creek War in 1891 and 1892 resulted in the state ending convict leasing.[129][130]

Despite New South promoters’ efforts, agriculture continued to dominate Tennessee’s economy.[131] The majority of freed slaves were forced into sharecropping during the latter 19th century, and many others worked as agricultural wage laborers.[132] In 1897, Tennessee celebrated its statehood centennial one year late with the Tennessee Centennial and International Exposition in Nashville.[133] A full-scale replica of the Parthenon in Athens was designed by architect William Crawford Smith and constructed for the celebration, owing to the city’s reputation as the «Athens of the South.»[134][135]

Earlier 20th century[edit]

Workers at the Norris Dam construction camp site in 1933

Due to increasing racial segregation and poor standards of living, many black Tennesseans fled to industrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest as part of the first wave of the Great Migration between 1915 and 1930.[136] Many residents of rural parts of Tennessee relocated to larger cities during this time for more lucrative employment opportunities.[127] As part of the Temperance movement, Tennessee became the first state in the nation to effectively ban the sale, transportation, and production of alcohol in a series of laws passed between 1907 and 1917.[137] During Prohibition, illicit production of moonshine became extremely common in East Tennessee, particularly in the mountains, and continued for many decades afterward.[138]

Sgt. Alvin C. York of Fentress County became one of the most famous and honored American soldiers of World War I. He received the Congressional Medal of Honor for single-handedly capturing an entire German machine gun regiment during the Meuse–Argonne offensive.[139] On July 9, 1918, Tennessee suffered the worst rail accident in U.S. history when two passenger trains collided head on in Nashville, killing 101 and injuring 171.[140] On August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the 36th and final state necessary to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave women the right to vote.[141] In 1925, John T. Scopes, a high school teacher in Dayton, was tried and convicted for teaching evolution in violation of the state’s recently passed Butler Act.[142] Scopes was prosecuted by former Secretary of State and presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan and defended by attorney Clarence Darrow. The case was intentionally publicized,[143] and highlighted the creationism-evolution controversy among religious groups.[144] In 1926, Congress authorized the establishment of a national park in the Great Smoky Mountains, which was officially established in 1934 and dedicated in 1940.[145]

When the Great Depression struck in 1929, much of Tennessee was severely impoverished even by national standards.[146] As part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was created in 1933 to provide electricity, jobs, flood control, improved waterway navigation, agricultural development, and economic modernization to the Tennessee River Valley.[147] The TVA built several hydroelectric dams in the state in the 1930s and 1940s, which inundated communities and thousands of farmland acreage, and forcibly displaced families via eminent domain.[148][149] The agency quickly grew into the country’s largest electric utility and initiated a period of dramatic economic growth and transformation that brought many new industries and employment opportunities to the state.[150][147]

During World War II, East Tennessee was chosen for the production of weapons-grade fissile enriched uranium as part of the Manhattan Project, a research and development undertaking led by the U.S. to produce the world’s first atomic bombs. The planned community of Oak Ridge was built to provide accommodations for the facilities and workers; the site was chosen due to the abundance of TVA electric power, its low population density, and its inland geography and topography, which allowed for the natural separation of the facilities and a low vulnerability to attack.[151][152] The Clinton Engineer Works was established as the production arm of the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge, which enriched uranium at three major facilities for use in atomic bombs. The first of the bombs was detonated in Los Alamos, New Mexico, in a test code-named Trinity, and the second, nicknamed «Little Boy», was dropped on Imperial Japan at the end of World War II.[153] After the war, the Oak Ridge National Laboratory became an institution for scientific and technological research.[154]

Mid-20th century to present[edit]

After the U.S. Supreme Court ruled racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, Oak Ridge High School in 1955 became the first school in Tennessee to be integrated.[155] The next year, nearby Clinton High School was integrated, and Tennessee National Guard troops were sent in after pro-segregationists threatened violence.[155] Between February and May 1960, a series of sit-ins at segregated lunch counters in Nashville organized by the Nashville Student Movement resulted in the desegregation of facilities in the city.[156] On April 4, 1968, James Earl Ray assassinated civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. in Memphis.[157] King had traveled there to support striking African American sanitation workers.[158][159]

The 1962 U.S. Supreme Court case Baker v. Carr arose out of a challenge to the longstanding rural bias of apportionment of seats in the Tennessee legislature and established the principle of «one man, one vote».[160][161] The construction of Interstate 40 through Memphis became a national talking point on the issue of eminent domain and grassroots lobbying when the Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) attempted to construct the highway through the city’s Overton Park. A local activist group spent many years contesting the project, and in 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court sided with the group and established the framework for judicial review of government agencies in the landmark case of Citizens to Preserve Overton Park v. Volpe.[162][163] TVA’s construction of the Tellico Dam in Loudon County became the subject of national controversy in the 1970s when the endangered snail darter fish was reported to be affected by the project. After lawsuits by environmental groups, the debate was decided by the U.S. Supreme Court case Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill in 1978, leading to amendments of the Endangered Species Act.[164]

The 1982 World’s Fair was held in Knoxville.[165] Also known as the Knoxville International Energy Exposition, the fair’s theme was «Energy Turns the World». The exposition was one of the most successful, and the most recent world’s fair to be held in the U.S.[166] In 1986, Tennessee held a yearlong celebration of the state’s heritage and culture called «Homecoming ’86».[167][168] Tennessee celebrated its bicentennial in 1996 with a yearlong celebration called «Tennessee 200». A new state park that traces the state’s history, Bicentennial Mall, was opened at the foot of Capitol Hill in Nashville.[169] The same year, the whitewater slalom events at the Atlanta Summer Olympic Games were held on the Ocoee River in Polk County.[170]

In 2002, Tennessee amended its constitution to establish a lottery.[171] In 2006, the state constitution was amended to outlaw same-sex marriage. This amendment was invalidated by the 2015 U.S. Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges.[172] On December 23, 2008, the largest industrial waste spill in United States history occurred at TVA’s Kingston Fossil Plant when more than 1.1 billion gallons of coal ash slurry was accidentally released into the Emory and Clinch Rivers.[173][174] The cleanup cost more than $1 billion and lasted until 2015.[175]

Geography[edit]

Tennessee is in the Southeastern United States. Culturally, most of the state is considered part of the Upland South, and the eastern third is part of Appalachia.[176] Tennessee covers roughly 42,143 square miles (109,150 km2), of which 926 square miles (2,400 km2), or 2.2%, is water. It is the 16th smallest state in land area. The state is about 440 miles (710 km) long from east to west and 112 miles (180 km) wide from north to south. Tennessee is geographically, culturally, economically, and legally divided into three Grand Divisions: East Tennessee, Middle Tennessee, and West Tennessee.[177] It borders eight other states: Kentucky and Virginia to the north, North Carolina to the east, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi on the south, and Arkansas and Missouri on the west. It is tied with Missouri as the state bordering the most other states.[178] Tennessee is trisected by the Tennessee River, and its geographical center is in Murfreesboro. Nearly three–fourths of the state is in the Central Time Zone, with most of East Tennessee on Eastern Time.[179] The Tennessee River forms most of the division between Middle and West Tennessee.[177]

Tennessee’s eastern boundary roughly follows the highest crests of the Blue Ridge Mountains, and the Mississippi River forms its western boundary.[180] Due to flooding of the Mississippi that has changed its path, the state’s western boundary deviates from the river in some places.[181] The northern border was originally defined as 36°30′ north latitude and the Royal Colonial Boundary of 1665, but due to faulty surveys, begins north of this line in the east, and to the west, gradually veers north before shifting south onto the actual 36°30′ parallel at the Tennessee River in West Tennessee.[180][182] Uncertainties in the latter 19th century over the location of the state’s border with Virginia culminated in the U.S. Supreme Court settling the matter in 1893, which resulted in the division of Bristol between the two states.[183] An 1818 survey erroneously placed Tennessee’s southern border 1 mile (1.6 km) south of the 35th parallel; Georgia legislators continue to dispute this placement, as it prevents Georgia from accessing the Tennessee River.[184]

Marked by a diversity of landforms and topographies, Tennessee features six principal physiographic provinces, from east to west, which are part of three larger regions: the Blue Ridge Mountains, Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, and Cumberland Plateau, part of the Appalachian Mountains; the Highland Rim and Nashville Basin, part of the Interior Low Plateaus of the Interior Plains; and the East Gulf Coastal Plain, part of the Atlantic Plains.[185][186] Other regions include the southern tip of the Cumberland Mountains, the Western Tennessee Valley, and the Mississippi Alluvial Plain. The state’s highest point, which is also the third-highest peak in eastern North America, is Clingmans Dome, at 6,643 feet (2,025 m) above sea level.[187] Its lowest point, 178 feet (54 m), is on the Mississippi River at the Mississippi state line in Memphis.[3] Tennessee has the most caves in the United States, with more than 10,000 documented.[188]

Geological formations in Tennessee largely correspond with the state’s topographic features, and, in general, decrease in age from east to west. The state’s oldest rocks are igneous strata more than 1 billion years old found in the Blue Ridge Mountains,[189][190] and the youngest deposits in Tennessee are sands and silts in the Mississippi Alluvial Plain and river valleys that drain into the Mississippi River.[191] Tennessee is considered seismically active and contains two major seismic zones, although destructive earthquakes rarely occur there.[192][193] The Eastern Tennessee Seismic Zone spans the entirety of East Tennessee from northwestern Alabama to southwestern Virginia, and is considered one of the most active zones in the Southeastern United States, frequently producing low-magnitude earthquakes.[194] The New Madrid Seismic Zone in the northwestern part of the state produced a series of devastating earthquakes between December 1811 and February 1812 that formed Reelfoot Lake near Tiptonville.[195]

Topography[edit]

The southwestern Blue Ridge Mountains lie within Tennessee’s eastern edge, and are divided into several subranges, namely the Great Smoky Mountains, Bald Mountains, Unicoi Mountains, Unaka Mountains, and Iron Mountains. These mountains, which average 5,000 feet (1,500 m) above sea level in Tennessee, contain some of the highest elevations in eastern North America. The state’s border with North Carolina roughly follows the highest peaks of this range, including Clingmans Dome. Most of the Blue Ridge area is protected by the Cherokee National Forest, the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and several federal wilderness areas and state parks.[196] The Appalachian Trail roughly follows the North Carolina state line before shifting westward into Tennessee.[197]

Stretching west from the Blue Ridge Mountains for about 55 miles (89 km) are the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians, also known as the Tennessee Valley[c] or Great Valley of East Tennessee. This area consists of linear parallel ridges separated by valleys that trend northeast to southwest, the general direction of the entire Appalachian range.[198] Most of these ridges are low, but some of the higher ones are commonly called mountains.[198] Numerous tributaries join to form the Tennessee River in the Ridge and Valley region.[199]

Fall Creek Falls, the tallest waterfall in the eastern United States, is located on the Cumberland Plateau

The Cumberland Plateau rises to the west of the Tennessee Valley, with an average elevation of 2,000 feet (610 m).[200] This landform is part of the larger Appalachian Plateau and consists mostly of flat-topped tablelands.[201] The plateau’s eastern edge is relatively distinct, but the western escarpment is irregular, containing several long, crooked stream valleys separated by rocky cliffs with numerous waterfalls.[202] The Cumberland Mountains, with peaks above 3,500 feet (1,100 m), comprise the northeastern part of the Appalachian Plateau in Tennessee, and the southeastern part of the Cumberland Plateau is divided by the Sequatchie Valley.[202] The Cumberland Trail traverses the eastern escarpment of the Cumberland Plateau and Cumberland Mountains.[203]

West of the Cumberland Plateau is the Highland Rim, an elevated plain that surrounds the Nashville Basin, a geological dome.[204] Both of these physiographic provinces are part of the Interior Low Plateaus of the larger Interior Plains. The Highland Rim is Tennessee’s largest geographic region, and is often split into eastern and western halves.[205] The Eastern Highland Rim is characterized by relatively level plains dotted by rolling hills, and the Western Highland Rim and western Nashville Basin are covered with uneven rounded knobs with steep ravines separated by meandering streams.[206] The Nashville Basin has rich, fertile farmland,[207] and porous limestone bedrock very close to the surface underlies both the Nashville Basin and Eastern Highland Rim.[208] This results in karst that forms numerous caves, sinkholes, depressions, and underground streams.[209]

West of the Highland Rim is the Western Tennessee Valley, which consists of about 10 miles (16 km) in width of hilly land along the banks of the Tennessee River.[210] West of this is the Gulf Coastal Plain, a broad feature that begins at the Gulf of Mexico and extends northward into southern Illinois.[211] The plain begins in the east with low rolling hills and wide stream valleys, known as the West Tennessee Highlands, and gradually levels out to the west.[212] It ends at steep loess bluffs overlooking the Mississippi embayment, the westernmost physiographic division of Tennessee, which is part of the larger Mississippi Alluvial Plain.[213] This flat 10 to 14 miles (16 to 23 km) wide strip is commonly known as the Mississippi Bottoms, and contains lowlands, floodplains, and swamps.[214][215]

Hydrology[edit]

Tennessee is drained by three major rivers, the Tennessee, Cumberland, and Mississippi. The Tennessee River begins at the juncture of the Holston and French Broad rivers in Knoxville, flows southwest to Chattanooga, and exits into Alabama before reemerging in the western part of the state and flowing north into Kentucky.[216] Its major tributaries include the Clinch, Little Tennessee, Hiwassee, Sequatchie, Elk, Beech, Buffalo, Duck, and Big Sandy rivers.[216] The Cumberland River flows through the north-central part of the state, emerging in the northeastern Highland Rim, passing through Nashville, turning northwest to Clarksville, and entering Kentucky east of the Tennessee River.[217] Its principal branches in Tennessee are the Obey, Caney Fork, Stones, Harpeth, and Red rivers.[217] The Mississippi River drains nearly all of West Tennessee.[218] Its tributaries are the Obion, Forked Deer, Hatchie, Loosahatchie, and Wolf rivers.[218] The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers operate many hydroelectric dams on the Tennessee and Cumberland rivers and their tributaries, which form large reservoirs throughout the state.[219]

About half the state’s land area is in the Tennessee Valley drainage basin of the Tennessee River.[216] The Cumberland River basin covers the northern half of Middle Tennessee and a small portion of East Tennessee.[217] A small part of north-central Tennessee is in the Green River watershed.[220] All three of these basins are tributaries of the Ohio River watershed. Most of West Tennessee is in the Lower Mississippi River watershed.[218] The entirety of the state is in the Mississippi River watershed, except for a small sliver near the southeastern corner traversed by the Conasauga River, which is part of the Mobile Bay watershed.[221]

Ecology[edit]

Cedar glades are an ecosystem that is found in regions of Middle Tennessee where limestone bedrock is close to the surface

Tennessee is within a temperate deciduous forest biome commonly known as the Eastern Deciduous Forest.[222] It has eight ecoregions: the Blue Ridge, Ridge and Valley, Central Appalachian, Southwestern Appalachian, Interior Low Plateaus, Southeastern Plains, Mississippi Valley Loess Plains, and Mississippi Alluvial Plain regions.[223] Tennessee is the most biodiverse inland state,[224] the Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the most biodiverse national park,[225][226] and the Duck River is the most biologically diverse waterway in North America.[227] The Nashville Basin is renowned for its diversity of flora and fauna.[228] Tennessee is home to 340 species of birds, 325 freshwater fish species, 89 mammals, 77 amphibians, and 61 reptiles.[225]

Forests cover about 52% of Tennessee’s land area, with oak–hickory the dominant type.[229] Appalachian oak–pine and cove hardwood forests are found in the Blue Ridge Mountains and Cumberland Plateau, and bottomland hardwood forests are common throughout the Gulf Coastal Plain.[230] Pine forests are also found throughout the state.[230] The Southern Appalachian spruce–fir forest in the highest elevations of the Blue Ridge Mountains is considered the second-most endangered ecosystem in the country.[231] Some of the last remaining large American chestnut trees grow in the Nashville Basin and are being used to help breed blight-resistant trees.[232] Middle Tennessee is home to many unusual and rare ecosystems known as cedar glades, which occur in areas with shallow limestone bedrock that is largely barren of overlying soil and contain many endemic plant species.[233]

Common mammals found throughout Tennessee include white-tailed deer, red and gray foxes, coyotes, raccoons, opossums, wild turkeys, rabbits, and squirrels. Black bears are found in the Blue Ridge Mountains and on the Cumberland Plateau. Tennessee has the third-highest number of amphibian species, with the Great Smoky Mountains home to the most salamander species in the world.[234] The state ranks second in the nation for the diversity of its freshwater fish species.[235]

Climate[edit]

Most of Tennessee has a humid subtropical climate, with the exception of some of the higher elevations in the Appalachians, which are classified as a cooler mountain temperate or humid continental climate.[236] The Gulf of Mexico is the dominant factor in Tennessee’s climate, with winds from the south responsible for most of the state’s annual precipitation. Generally, the state has hot summers and mild to cool winters with generous precipitation throughout the year. The highest average monthly precipitation usually occurs between December and April. The driest months, on average, are August to October. The state receives an average of 50 inches (130 cm) of precipitation annually. Snowfall ranges from 5 inches (13 cm) in West Tennessee to over 80 inches (200 cm) in East Tennessee’s highest mountains.[237][238]

Summers are generally hot and humid, with most of the state averaging a high of around 90 °F (32 °C). Winters tend to be mild to cool, decreasing in temperature at higher elevations. For areas outside the highest mountains, the average overnight lows are generally near freezing. The highest recorded temperature was 113 °F (45 °C) at Perryville on August 9, 1930, while the lowest recorded temperature was −32 °F (−36 °C) at Mountain City on December 30, 1917.[239]

While Tennessee is far enough from the coast to avoid any direct impact from a hurricane, its location makes it susceptible to the remnants of tropical cyclones, which weaken over land and can cause significant rainfall.[240] The state annually averages about 50 days of thunderstorms, which can be severe with large hail and damaging winds.[241] Tornadoes are possible throughout the state, with West and Middle Tennessee the most vulnerable. The state averages 15 tornadoes annually.[242] They can be severe, and the state leads the nation in the percentage of total tornadoes that have fatalities.[243] Winter storms such as in 1993 and 2021 occur occasionally, and ice storms are fairly common. Fog is a persistent problem in some areas, especially in East Tennessee.[244]

| Monthly Normal High and Low Temperatures For Various Tennessee Cities (F)[245] | ||||||||||||

| City | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bristol | 44/25 | 49/27 | 57/34 | 66/41 | 74/51 | 81/60 | 85/64 | 84/62 | 79/56 | 68/43 | 58/35 | 48/27 |

| Chattanooga | 50/31 | 54/33 | 63/40 | 72/47 | 79/56 | 86/65 | 90/69 | 89/68 | 82/62 | 72/48 | 61/40 | 52/33 |

| Knoxville | 47/30 | 52/33 | 61/40 | 71/48 | 78/57 | 85/65 | 88/69 | 87/68 | 81/62 | 71/50 | 60/41 | 50/34 |

| Memphis | 50/31 | 55/36 | 63/44 | 72/52 | 80/61 | 89/69 | 92/73 | 92/72 | 86/65 | 75/52 | 62/43 | 52/34 |

| Nashville | 47/28 | 52/31 | 61/39 | 70/47 | 78/57 | 85/65 | 89/70 | 89/69 | 82/61 | 71/49 | 59/40 | 49/32 |

Cities, towns, and counties[edit]

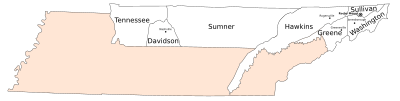

Tennessee is divided into 95 counties, each of which has a county seat.[246] The state has 340 municipalities in total.[247] The Office of Management and Budget designates ten metropolitan areas in Tennessee, four of which extend into neighboring states.[248]

Nashville is Tennessee’s capital and largest city, with nearly 700,000 residents.[249] Its 13-county metropolitan area has been the state’s largest since the early 1990s and is one of the nation’s fastest-growing metropolitan areas, with about 2 million residents.[250] Memphis, with more than 630,000 inhabitants, was the state’s largest city until 2016, when Nashville surpassed it.[2] It is in Shelby County, Tennessee’s largest county in both population and land area.[251] Knoxville, with about 190,000 inhabitants, and Chattanooga, with about 180,000 residents, are the third- and fourth-largest cities, respectively.[249] Clarksville is a significant population center, with about 170,000 residents.[249] Murfreesboro is the sixth-largest city and Nashville’s largest suburb, with more than 150,000 residents.[249] In addition to the major cities, the Tri-Cities of Kingsport, Bristol, and Johnson City are considered the sixth major population center.[252]

|

Largest cities or towns in Tennessee Source:[249] |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||

Nashville  Memphis |

1 | Nashville | Davidson | 689,447 |  Knoxville Chattanooga |

| 2 | Memphis | Shelby | 633,104 | ||

| 3 | Knoxville | Knox | 190,740 | ||

| 4 | Chattanooga | Hamilton | 181,099 | ||

| 5 | Clarksville | Montgomery | 166,722 | ||

| 6 | Murfreesboro | Rutherford | 152,769 | ||

| 7 | Franklin | Williamson | 83,454 | ||

| 8 | Johnson City | Washington | 71,046 | ||

| 9 | Jackson | Madison | 68,205 | ||

| 10 | Hendersonville | Sumner | 61,753 |

Demographics[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 35,691 | — | |

| 1800 | 105,602 | 195.9% | |

| 1810 | 261,727 | 147.8% | |

| 1820 | 422,823 | 61.6% | |

| 1830 | 681,904 | 61.3% | |

| 1840 | 829,210 | 21.6% | |

| 1850 | 1,002,717 | 20.9% | |

| 1860 | 1,109,801 | 10.7% | |

| 1870 | 1,258,520 | 13.4% | |

| 1880 | 1,542,359 | 22.6% | |

| 1890 | 1,767,518 | 14.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,020,616 | 14.3% | |

| 1910 | 2,184,789 | 8.1% | |

| 1920 | 2,337,885 | 7.0% | |

| 1930 | 2,616,556 | 11.9% | |

| 1940 | 2,915,841 | 11.4% | |

| 1950 | 3,291,718 | 12.9% | |

| 1960 | 3,567,089 | 8.4% | |

| 1970 | 3,923,687 | 10.0% | |

| 1980 | 4,591,120 | 17.0% | |

| 1990 | 4,877,185 | 6.2% | |

| 2000 | 5,689,283 | 16.7% | |

| 2010 | 6,346,105 | 11.5% | |

| 2020 | 6,910,840 | 8.9% | |

| 2022 (est.) | 7,051,339 | 2.0% | |

| Source: 1910–2020[253] |

The 2020 United States census reported Tennessee’s population at 6,910,840, an increase of 564,735, or 8.90%, since the 2010 census.[4] Between 2010 and 2019, the state received a natural increase of 143,253 (744,274 births minus 601,021 deaths), and an increase from net migration of 338,428 people into the state. Immigration from outside the U.S. resulted in a net increase of 79,086, and migration within the country produced a net increase of 259,342.[254] Tennessee’s center of population is in Murfreesboro in Rutherford County.[255]

According to the 2010 census, 6.4% of Tennessee’s population were under age 5, 23.6% were under 18, and 13.4% were 65 or older.[256] In recent years, Tennessee has been a top source of domestic migration, receiving an influx of people relocating from places such as California, the Northeast, and the Midwest due to the low cost of living and booming employment opportunities.[257][258] In 2019, about 5.5% of Tennessee’s population was foreign-born. Of the foreign-born population, approximately 42.7% were naturalized citizens and 57.3% non-citizens.[259] The foreign-born population consisted of approximately 49.9% from Latin America, 27.1% from Asia, 11.9% from Europe, 7.7% from Africa, 2.7% from Northern America, and 0.6% from Oceania.[260]

With the exception of a slump in the 1980s, Tennessee has been one of the fastest-growing states in the nation since 1970, benefiting from the larger Sun Belt phenomenon.[261] The state has been a top destination for people relocating from Northeastern and Midwestern states. This time period has seen the birth of new economic sectors in the state and has positioned the Nashville and Clarksville metropolitan areas as two of the fastest-growing regions in the country.[262]

Ethnicity[edit]

| Race and Ethnicity[263] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 70.9% | 74.6% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 15.7% | 17.0% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[d] | — | 6.9% | ||

| Asian | 1.9% | 2.5% | ||

| Native American | 0.2% | 2.0% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.1% | 0.1% | ||

| Other | 0.1% | 0.3% |

Map of counties in Tennessee by racial plurality, per the 2020 U.S. census

-

Non-Hispanic White 50–60%

60–70%

70–80%

80–90%

90%+

Black or African American 50–60%

| Historical racial composition | 1940[264] | 1970[264] | 1990[264] | 2000[e][265] | 2010[265] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 82.5% | 83.9% | 83.0% | 80.2% | 77.6% |

| Black | 17.4% | 15.8% | 16.0% | 16.4% | 16.7% |

| Asian | — | 0.1% | 0.7% | 1.0% | 1.4% |

| Native | — | 0.1% | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

— | — | – | – | 0.1% |

| Other race | — | — | 0.2% | 1.0% | 2.2% |

| Two or more races | — | — | – | 1.1% | 1.7% |

In 2020, 6.9% of the total population was of Hispanic or Latino origin (of any race), up from 4.6% in 2010. Between 2000 and 2010, Tennessee’s Hispanic population grew by 134.2%, the third-highest rate of any state.[266] In 2020, Non-Hispanic or Latino Whites were 70.9% of the population, compared to 57.7% of the population nationwide.[267] In 2010, the five most common self-reported ethnic groups in the state were American (26.5%), English (8.2%), Irish (6.6%), German (5.5%), and Scotch-Irish (2.7%).[268] Most Tennesseans who self-identify as having American ancestry are of English and Scotch-Irish ancestry. An estimated 21–24% of Tennesseans are of predominantly English ancestry.[269][270]

Religion[edit]

Since colonization, Tennessee has always been predominantly Christian. About 81% of the population identifies as Christian, with Protestants making up 73% of the population. Of the Protestants in the state, Evangelical Protestants compose 52% of the population, Mainline Protestants 13%, and Historically Black Protestants 8%. Roman Catholics make up 6%, Mormons 1%, and Orthodox Christians less than 1%.[271] The largest denominations by number of adherents are the Southern Baptist Convention, the United Methodist Church, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Churches of Christ.[272] Muslims and Jews each make up about 1% of the population, and adherents of other religions make up about 3% of the population. About 14% of Tennesseans are non-religious, with 11% identifying as «Nothing in particular», 3% as agnostics, and 1% as atheists.[271]

Tennessee is included in most definitions of the Bible Belt, and is ranked as one of the nation’s most religious states.[273] Several Protestant denominations have their headquarters in Tennessee, including the Southern Baptist Convention and National Baptist Convention (in Nashville); the Church of God in Christ and the Cumberland Presbyterian Church (in Memphis);[274] and the Church of God and the Church of God of Prophecy (in Cleveland);[275][276] and the National Association of Free Will Baptists (in Antioch).[277] Nashville has publishing houses of several denominations.[278]

Economy[edit]

A geomap showing the counties of Tennessee colored by the relative range of that county’s median income.

Chart showing poverty in Tennessee, by age and gender (red = female)

As of 2021, Tennessee had a gross state product of $418.3 billion.[279] In 2020, the state’s per capita personal income was $30,869. The median household income was $54,833.[259] About 13.6% percent of the population was below the poverty line.[4] In 2019, the state reported a total employment of 2,724,545 and a total number of 139,760 employer establishments.[4] Tennessee is a right-to-work state, like most of its Southern neighbors.[280] Unionization has historically been low and continues to decline, as in most of the U.S.[281]

Taxation[edit]

Tennessee has a reputation as a low-tax state and is usually ranked as one of the five states with the lowest tax burden on residents.[282] It is one of nine states that do not have a general income tax; the sales tax is the primary means of funding the government.[283] The Hall income tax was imposed on most dividends and interest at a rate of 6% but was completely phased out by 2021.[284] The first $1,250 of individual income and $2,500 of joint income was exempt from this tax.[285] Property taxes are the primary source of revenue for local governments.[286]

The state’s sales and use tax rate for most items is 7%, the second-highest in the nation, along with Mississippi, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and Indiana. Food is taxed at 4%, but candy, dietary supplements, and prepared foods are taxed at 7%.[287] Local sales taxes are collected in most jurisdictions at rates varying from 1.5% to 2.75%, bringing the total sales tax between 8.5% and 9.75%. The average combined rate is about 9.5%, the nation’s highest average sales tax.[288] Intangible property tax is assessed on the shares of stockholders of any loan, investment, insurance, or for-profit cemetery companies. The assessment ratio is 40% of the value times the jurisdiction’s tax rate.[286] Since 2016, Tennessee has had no inheritance tax.[289]

Agriculture[edit]

Tennessee has the eighth-most farms in the nation, which cover more than 40% of its land area and have an average size of about 155 acres (0.63 km2).[290] Cash receipts for crops and livestock have an estimated annual value of $3.5 billion, and the agriculture sector has an estimated annual impact of $81 billion on the state’s economy.[290] Beef cattle is the state’s largest agricultural commodity, followed by broilers and poultry.[16] Tennessee ranks 12th in the nation for the number of cattle, with more than half of its farmland dedicated to cattle grazing.[291][290] Soybeans and corn are the state’s first and second-most common crops, respectively,[16] and are most heavily grown in West and Middle Tennessee, especially the northwestern corner of the state.[292][293] Tennessee ranks seventh in the nation in cotton production, most of which is grown in the fertile soils of central West Tennessee.[294]

The state ranks fourth nationwide in the production of tobacco, which is predominantly grown in the Ridge-and-Valley region of East Tennessee.[295] Tennessee farmers are also known worldwide for their cultivation of tomatoes and horticultural plants.[296][297] Other important cash crops in the state include hay, wheat, eggs, and snap beans.[290][295] The Nashville Basin is a top equestrian region, due to soils that produce grass favored by horses. The Tennessee Walking Horse, first bred in the region in the late 18th century, is one of the world’s most recognized horse breeds.[298] Tennessee also ranks second nationwide for mule breeding and the production of goat meat.[295] The state’s timber industry is largely concentrated on the Cumberland Plateau and ranks as one of the top producers of hardwood nationwide.[299]

Industry[edit]

Until World War II, Tennessee, like most Southern states, remained predominantly agrarian. Chattanooga became one of the first industrial cities in the south in the decades after the Civil War, when many factories, including iron foundries, steel mills, and textile mills were constructed there.[127] But most of Tennessee’s industrial growth began with the federal investments in the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) and the Manhattan Project in the 1930s and 1940s. The state’s industrial and manufacturing sector continued to expand in the succeeding decades, and Tennessee is now home to more than 2,400 advanced manufacturing establishments, which produce a total of more than $29 billion worth of goods annually.[300]

The automotive industry is Tennessee’s largest manufacturing sector and one of the nation’s largest.[301] Nissan’s assembly plant in Smyrna is the largest automotive assembly plant in North America.[302] Two other automakers have assembly plants in Tennessee: General Motors in Spring Hill and Volkswagen in Chattanooga.[303] Ford is constructing an assembly plant in Stanton that is expected to be operational in 2025.[304] In addition, the state contains more than 900 automotive suppliers.[305] Nissan and Mitsubishi Motors have their North American corporate headquarters in Franklin.[306][307] The state is also one of the top producers of food and drink products, its second-largest manufacturing sector.[308] A number of well-known brands originated in Tennessee, and even more are produced there.[309] Tennessee also ranks as one of the largest producers of chemicals.[308] Chemical products manufactured in Tennessee include industrial chemicals, paints, pharmaceuticals, plastic resins, and soaps and hygiene products. Additional important products manufactured in Tennessee include fabricated metal products, electrical equipment, consumer electronics and electrical appliances, and nonelectrical machinery.[309]

Business[edit]

Tennessee’s commercial sector is dominated by a wide variety of companies, but its largest service industries include health care, transportation, music and entertainment, banking, and finance. Large corporations with headquarters in Tennessee include FedEx, AutoZone, International Paper, and First Horizon Corporation, all based in Memphis; Pilot Corporation and Regal Entertainment Group in Knoxville; Hospital Corporation of America based in Nashville; Unum in Chattanooga; Acadia Senior Living and Community Health Systems in Franklin; Dollar General in Goodlettsville, and LifePoint Health, Tractor Supply Company, and Delek US in Brentwood.[310][311]

Since the 1990s, the geographical area between Oak Ridge and Knoxville has been known as the Tennessee Technology Corridor, with more than 500 high-tech firms in the region.[312] The research and development industry in Tennessee is also one of the largest employment sectors, mainly due to the prominence of Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and the Y-12 National Security Complex in the city of Oak Ridge. ORNL conducts scientific research in materials science, nuclear physics, energy, high-performance computing, systems biology, and national security, and is the largest national laboratory in the Department of Energy (DOE) system by size.[313][154] The technology sector is also a rapidly growing industry in Middle Tennessee, particularly in the Nashville metropolitan area.[314]

Energy and mineral production[edit]

Tennessee’s electric utilities are regulated monopolies, as in many other states.[315][316] The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) owns over 90% of the state’s generating capacity.[317] Nuclear power is Tennessee’s largest source of electricity generation, producing about 43.4% of its power in 2021. The same year, 22.4% of the power was produced from coal, 17.8% from natural gas, 15.8% from hydroelectricity, and 1.3% from other renewables. About 59.7% of the electricity generated in Tennessee produces no greenhouse gas emissions.[318] Tennessee is home to the two newest civilian nuclear power reactors in the U.S., at the Watts Bar Nuclear Plant in Rhea County.[319] Tennessee was also an early leader in hydroelectric power,[320] and today is the third-largest hydroelectric power-producing state east of the Rocky Mountains.[321] Tennessee is a net consumer of electricity, receiving power from other TVA facilities in neighboring states.[322]

Tennessee has very little petroleum and natural gas reserves, but is home to one oil refinery, in Memphis.[321] Bituminous coal is mined in small quantities in the Cumberland Plateau and Cumberland Mountains.[323] There are sizable reserves of lignite coal in West Tennessee that remain untapped.[323] Coal production in Tennessee peaked in 1972, and today less than 0.1% of coal in the U.S. comes from Tennessee.[321] Tennessee is the nation’s leading producer of ball clay.[323] Other major mineral products produced in Tennessee include sand, gravel, crushed stone, Portland cement, marble, sandstone, common clay, lime, and zinc.[323][324] The Copper Basin, in Tennessee’s southeastern corner in Polk County, was one of the nation’s most productive copper mining districts between the 1840s and 1980s, and supplied about 90% of the copper the Confederacy used during the Civil War.[325][326][327] Mining activities in the basin resulted in a major environmental disaster, which left the surrounding landscape barren for more than a century.[328] Iron ore was another major mineral mined in Tennessee until the early 20th century.[329] Tennessee was also a top producer of phosphate until the early 1990s.[330]

Tourism[edit]

Tennessee is the 11th-most visited state in the nation,[332] receiving a record of 126 million tourists in 2019.[333][334][335] Its top tourist attraction is the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, the most visited national park in the U.S., with more than 14 million visitors annually.[331] The park anchors a large tourism industry based primarily in nearby Gatlinburg and Pigeon Forge, which includes Dollywood, the most visited ticketed attraction in Tennessee.[336] Attractions related to Tennessee’s musical heritage are spread throughout the state.[337][338] Other top attractions include the Tennessee State Museum and Parthenon in Nashville; the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis; Lookout Mountain, the Chattanooga Choo-Choo Hotel, Ruby Falls, and the Tennessee Aquarium in Chattanooga; the American Museum of Science and Energy in Oak Ridge, the Bristol Motor Speedway, Jack Daniel’s Distillery in Lynchburg, and the Hiwassee and Ocoee rivers in Polk County.[336]

The National Park Service preserves four Civil War battlefields in Tennessee: Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, Stones River National Battlefield, Shiloh National Military Park, and Fort Donelson National Battlefield.[339] The NPS also operates Big South Fork National River and Recreation Area, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail, Trail of Tears National Historic Trail, Andrew Johnson National Historic Site, and the Manhattan Project National Historical Park.[340] Tennessee is home to eight National Scenic Byways, including the Natchez Trace Parkway, the East Tennessee Crossing Byway, the Great River Road, the Norris Freeway, Cumberland National Scenic Byway, Sequatchie Valley Scenic Byway, The Trace, and the Cherohala Skyway.[341][342] Tennessee maintains 56 state parks, covering 132,000 acres (530 km2).[343] Many reservoirs created by TVA dams have also generated water-based tourist attractions.[344]

Culture[edit]

A culturally diverse state, Tennessee blends Appalachian and Southern flavors, which originate from its English, Scotch-Irish, and African roots, and has evolved as it has grown. Its Grand Divisions also manifest into distinct cultural regions, with East Tennessee commonly associated with Southern Appalachia,[345] and Middle and West Tennessee commonly associated with Upland Southern culture.[346] Parts of West Tennessee, especially Memphis, are sometimes considered part of the Deep South.[347] The Tennessee State Museum in Nashville chronicles the state’s history and culture.[348]

Tennessee is perhaps best known culturally for its musical heritage and contributions to the development of many forms of popular music.[349][350] Notable authors with ties to Tennessee include Cormac McCarthy, Peter Taylor, James Agee, Francis Hodgson Burnett, Thomas S. Stribling, Ida B. Wells, Nikki Giovanni, Shelby Foote, Ann Patchett, Ishmael Reed, and Randall Jarrell. The state’s well-known contributions to Southern cuisine include Memphis-style barbecue, Nashville hot chicken, and Tennessee whiskey.[351]

Music[edit]

Tennessee has played a critical role in the development of many forms of American popular music, including blues, country, rock and roll, rockabilly, soul, bluegrass, Contemporary Christian, and gospel. Many consider Memphis’s Beale Street the epicenter of the blues, with musicians such as W. C. Handy performing in its clubs as early as 1909.[349] Memphis was historically home to Sun Records, where musicians such as Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, Roy Orbison, and Charlie Rich began their recording careers, and where rock and roll took shape in the 1950s.[349] Stax Records in Memphis became one of the most important labels for soul artists in the late 1950s and 1960s, and a subgenre known as Memphis soul emerged.[352] The 1927 Victor recording sessions in Bristol generally mark the beginning of the country music genre and the rise of the Grand Ole Opry in the 1930s helped make Nashville the center of the country music recording industry.[353][354] Nashville became known as «Music City», and the Grand Ole Opry remains the nation’s longest-running radio show.[350]

Many museums and historic sites recognize Tennessee’s role in nurturing various forms of popular music, including Sun Studio, Memphis Rock N’ Soul Museum, Stax Museum of American Soul Music, and Blues Hall of Fame in Memphis, the Ryman Auditorium, Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, Musicians Hall of Fame and Museum, National Museum of African American Music, and Music Row in Nashville, the International Rock-A-Billy Museum in Jackson, the Mountain Music Museum in Kingsport, and the Birthplace of Country Music Museum in Bristol.[355] The Rockabilly Hall of Fame, an online site recognizing the development of rockabilly, is also based in Nashville. Several annual music festivals take place throughout the state, the largest of which are the Beale Street Music Festival in Memphis, the CMA Music Festival in Nashville, Bonnaroo in Manchester, and Riverbend in Chattanooga.[356]

Education[edit]

Education in Tennessee is administered by the Tennessee Department of Education.[357] The state Board of Education has 11 members: one from each Congressional district, a student member, and the executive director of the Tennessee Higher Education Commission (THEC), who serves as ex-officio nonvoting member.[358] Public primary and secondary education systems are operated by county, city, or special school districts to provide education at the local level, and operate under the direction of the Tennessee Department of Education.[357] The state also has many private schools.[359]

The state enrolls approximately 1 million K–12 students in 137 districts.[360] In 2021, the four-year high school graduation rate was 88.7%, a decrease of 1.2% from the previous year.[361] According to the most recent data, Tennessee spends $9,544 per student, the 8th lowest in the nation.[362]

Colleges and universities[edit]

Vanderbilt University in Nashville is consistently ranked as one of the top research institutions in the nation

Public higher education is overseen by the Tennessee Higher Education Commission (THEC), which provides guidance to the state’s two public university systems. The University of Tennessee system operates four primary campuses in Knoxville, Chattanooga, Martin, and Pulaski; a Health Sciences Center in Memphis; and an aerospace research facility in Tullahoma.[363] The Tennessee Board of Regents (TBR), also known as The College System of Tennessee, operates 13 community colleges and 27 campuses of the Tennessee Colleges of Applied Technology (TCAT).[364] Until 2017, the TBR also operated six public universities in the state; it now only gives them administrative support.[365]

In 2014, the Tennessee General Assembly created the Tennessee Promise, which allows in-state high school graduates to enroll in two-year post-secondary education programs such as associate degrees and certificates at community colleges and trade schools in Tennessee tuition-free, funded by the state lottery, if they meet certain requirements.[366] The Tennessee Promise was created as part of then-governor Bill Haslam’s «Drive to 55» program, which set a goal of increasing the number of college-educated residents to at least 55% of the state’s population.[366] The program has also received national attention, with multiple states having since created similar programs modeled on the Tennessee Promise.[367]

Tennessee has 107 private institutions.[368] Vanderbilt University in Nashville is consistently ranked as one of the nation’s leading research institutions.[369] Nashville is often called the «Athens of the South» due to its many colleges and universities.[370] Tennessee is also home to six historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs).[371]

Media[edit]

Tennessee is home to more than 120 newspapers. The most-circulated paid newspapers in the state include The Tennessean in Nashville, The Commercial Appeal in Memphis, the Knoxville News Sentinel, the Chattanooga Times Free Press, and The Leaf-Chronicle in Clarksville, The Jackson Sun, and The Daily News Journal in Murfreesboro. All of these except the Times Free Press are owned by Gannett.[372]

Six television media markets—Nashville, Memphis, Knoxville, Chattanooga, Tri-Cities, and Jackson—are based in Tennessee. The Nashville market is the third-largest in the Upland South and the ninth-largest in the southeastern United States, according to Nielsen Media Research. Small sections of the Huntsville, Alabama and Paducah, Kentucky-Cape Girardeau, Missouri-Harrisburg, Illinois markets also extend into the state.[373] Tennessee has 43 full-power and 41 low-power television stations[374] and more than 450 Federal Communications Commission (FCC)-licensed radio stations.[375] The Grand Ole Opry, based in Nashville, is the longest-running radio show in the country, having broadcast continuously since 1925.[350]

Transportation[edit]

The Tennessee Department of Transportation (TDOT) is the primary agency that is tasked with regulating and maintaining Tennessee’s transportation infrastructure.[376] Tennessee is currently one of five states with no transportation-related debts.[377][378]

Roads[edit]

Interstate 40 traverses Tennessee from east to west, and serves the state’s three largest cities.

Tennessee has 96,167 miles (154,766 km) of roads, of which 14,109 miles (22,706 km) are maintained by the state.[379] Of the state’s highways, 1,233 miles (1,984 km) are part of the Interstate Highway System. Tennessee has no tolled roads or bridges but has the sixth-highest mileage of high-occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes, which are utilized on freeways in the congestion-prone Nashville and Memphis metropolitan areas.[380]

Interstate 40 (I-40) is the longest Interstate Highway in Tennessee, traversing the state for 455 miles (732 km).[381] Known as «Tennessee’s Main Street», I-40 serves the major cities of Memphis, Nashville, and Knoxville, and throughout its entire length in Tennessee, one can observe the diversity of the state’s geography and landforms.[382][200] I-40’s branch interstates include I-240 in Memphis; I-440 in Nashville; I-840 around Nashville; I-140 from Knoxville to Maryville; and I-640 in Knoxville. In a north–south orientation, from west to east, are interstates 55, which serves Memphis; 65, which passes through Nashville; 75, which serves Chattanooga and Knoxville; and 81, which begins east of Knoxville, and serves Bristol to the northeast. I-24 is an east–west interstate that enters the state in Clarksville, passes through Nashville, and terminates in Chattanooga. I-26, although technically an east–west interstate, begins in Kingsport and runs southwardly through Johnson City before exiting into North Carolina. I-155 is a branch route of I-55 that serves the northwestern part of the state. I-275 is a short spur route in Knoxville. I-269 runs from Millington to Collierville, serving as an outer bypass of Memphis.[383][381]

Airports[edit]

Major airports in Tennessee include Nashville International Airport (BNA), Memphis International Airport (MEM), McGhee Tyson Airport (TYS) outside of Knoxville, Chattanooga Metropolitan Airport (CHA), Tri-Cities Regional Airport (TRI) in Blountville, and McKellar-Sipes Regional Airport (MKL) in Jackson. Because Memphis International Airport is the hub of FedEx Corporation, it is the world’s busiest cargo airport.[384] The state also has 74 general aviation airports and 148 heliports.[379]

Railroads[edit]

For passenger rail service, Memphis and Newbern are served by the Amtrak City of New Orleans line on its run between Chicago and New Orleans.[385] Nashville is served by the Music City Star commuter rail service.[386] Tennessee currently has 2,604 miles (4,191 km) of freight trackage in operation,[387] most of which are owned by CSX Transportation.[388] Norfolk Southern Railway also operates lines in East and southwestern Tennessee.[389] BNSF operates a major intermodal facility in Memphis.

Waterways[edit]

Tennessee has a total of 976 miles (1,571 km) of navigable waterways, the 11th highest in the nation.[379] These include the Mississippi, Tennessee, and Cumberland rivers.[390] Five inland ports are located in the state, including the Port of Memphis, which is the fifth-largest in the United States and the second largest on the Mississippi River.[391]

Law and government[edit]