|

Tupac Shakur |

|

|---|---|

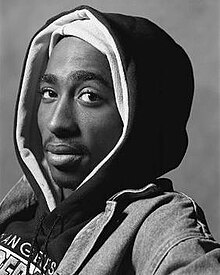

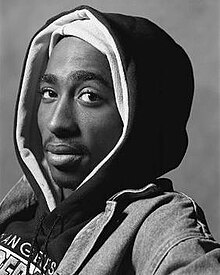

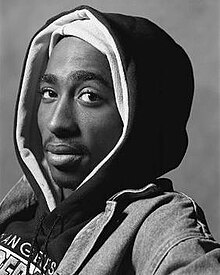

Shakur in 1991 |

|

| Born |

Lesane Parish Crooks June 16, 1971 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 13, 1996 (aged 25)

Las Vegas, Nevada, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Drive-by homicide (gunshot wounds) |

| Other names |

|

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1989–1996 |

| Spouse |

Keisha Morris (m. 1995; ann. 1996) |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Origin | Marin City, California, U.S. |

| Genres |

|

| Labels |

|

| Formerly of |

|

| Website | www.2pac.com |

| Signature | |

|

Tupac Amaru Shakur (; born Lesane Parish Crooks, June 16, 1971 – September 13, 1996), also known by his stage names 2Pac and Makaveli, was an American rapper and actor. He is widely considered one of the most influential rappers of all time.[1][2] Shakur is among the best-selling music artists, having sold more than 75 million records worldwide. Much of Shakur’s music has been noted for addressing contemporary social issues that plagued inner cities, and he is considered a symbol of activism against inequality.

Shakur was born in New York City to parents who were both political activists and Black Panther Party members. Raised by his mother, Afeni Shakur, he relocated to Baltimore in 1984 and to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1988. With the release of his debut album 2Pacalypse Now in 1991, he became a central figure in West Coast hip hop for his conscious rap lyrics.[3][4] Shakur achieved further critical and commercial success with his follow-up albums Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z… (1993) and Me Against the World (1995).[5] His Diamond certified album All Eyez on Me (1996), the first double-length album in hip-hop history, abandoned his introspective lyrics for volatile gangsta rap.[6] In addition to his music career, Shakur also found considerable success as an actor, with his starring roles in Juice (1992), Poetic Justice (1993), Above the Rim (1994), Bullet (1996), Gridlock’d (1997), and Gang Related (1997).

During the later part of his career, Shakur was shot five times in the lobby of a New York recording studio and experienced legal troubles, including incarceration. In 1995, Shakur served eight months in prison on sexual abuse charges, but was released pending an appeal of his conviction. Following his release, he signed to Marion «Suge» Knight’s label Death Row Records and became heavily involved in the growing East Coast–West Coast hip hop rivalry.[7] On September 7, 1996, Shakur was shot four times by an unidentified assailant in a drive-by shooting in Las Vegas; he died six days later. Following his murder, Shakur’s friend-turned-rival, the Notorious B.I.G., was at first considered a suspect due to their public feud; he was also murdered in another drive-by shooting six months later in March 1997 while visiting Los Angeles.[8][9]

Shakur’s double-length posthumous album Greatest Hits (1998) is one of his two releases—and one of only nine hip hop albums—to have been certified Diamond in the United States.[10] Five more albums have been released since Shakur’s death, including his critically acclaimed posthumous album The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory (1996)[11] under his stage name Makaveli, all of which have been certified Platinum in the United States.[12] In 2002, Shakur was inducted into the Hip-Hop Hall of Fame.[13] In 2017, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility.[14] Rolling Stone ranked Shakur among the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.[15]

Early life

Shakur was born on June 16, 1971, in the East Harlem section of Upper Manhattan, New York City.[16] While born Lesane Parish Crooks,[17][18][19] at age one he was renamed Tupac Amaru Shakur.[20] He was named after Túpac Amaru II, the descendant of the last Incan ruler, who was executed in Peru in 1781 after his failed revolt against Spanish rule.[21] Shakur’s mother Afeni Shakur explained, «I wanted him to have the name of revolutionary, indigenous people in the world. I wanted him to know he was part of a world culture and not just from a neighborhood.»[20]

Shakur had an older stepbrother, Mopreme «Komani» Shakur, and a half-sister, Sekyiwa Shakur, two years his junior.[22]

Panther heritage

Shakur’s parents, Afeni Shakur—born Alice Faye Williams in North Carolina—and his biological father, Billy Garland, had been active Black Panther Party members in New York in the late 1960s and early 1970s.[23] A month before Shakur’s birth, his mother was tried in New York City as part of the Panther 21 criminal trial. She was acquitted of over 150 charges.[24][25]

Other family members who were involved in the Black Panthers’ Black Liberation Army were convicted of serious crimes and imprisoned, including Shakur’s stepfather, Mutulu Shakur, who spent four years among the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives. Mutulu Shakur was apprehended in 1986 and subsequently convicted for a 1981 robbery of a Brinks armored truck, during which police officers and a guard were killed.[26]

Shakur’s godfather, Elmer «Geronimo» Pratt, a high-ranking Black Panther, was convicted of murdering a school teacher during a 1968 robbery. After spending 27 years in prison, his conviction was overturned due to the prosecution’s having concealed evidence that proved his innocence.[27][28]

Shakur’s godmother, Assata Shakur, is a former member of the Black Liberation Army, who was convicted of the first-degree murder of a New Jersey State Trooper and is still wanted by the FBI.[29]

The East Harlem neighborhood of New York City where Shakur was born

Education

In the 1980s, Shakur’s mother found it difficult to find work and she struggled with drug addiction.[30] In 1984, his family moved from New York City to Baltimore, Maryland.[31] He attended eighth grade at Roland Park Middle School, then ninth grade at Paul Laurence Dunbar High School.[31] He transferred to the Baltimore School for the Arts in the tenth grade, where he studied acting, poetry, jazz, and ballet.[32][33] He performed in Shakespeare’s plays—depicting timeless themes, now seen in gang warfare, he would recall[34]—and as the Mouse King role in The Nutcracker ballet.[26]

At the Baltimore School for the Arts, Shakur befriended actress Jada Pinkett, who became a subject of some of his poems.[35] With his friend Dana «Mouse» Smith as beatbox, he won competitions as reputedly the school’s best rapper.[36] Also known for his humor, he could mix with all crowds.[37] He listened to a diverse range of music that included Kate Bush, Culture Club, Sinéad O’Connor, and U2.[38]

Upon connecting with the Baltimore Young Communist League USA,[39][40][41] Shakur dated the daughter of the director of the local chapter of the Communist Party USA.[42]

In 1988, Shakur moved to Marin City, California, an impoverished community in the San Francisco Bay Area.[43][44] In nearby Mill Valley, he attended Tamalpais High School,[45] where he performed in several theater productions.[46] Shakur did not graduate from high school, but he later earned his GED.[47]

Music career

MC New York

Shakur began recording under the stage name MC New York in 1989.[48] That year, he began attending the poetry classes of Leila Steinberg, and she soon became his manager.[49][43] Steinberg organized a concert for Shakur and his rap group Strictly Dope. Steinberg managed to get Shakur signed by Atron Gregory, manager of the rap group Digital Underground.[43] In 1990, Gregory placed him with the Underground as a roadie and backup dancer.[43][50]

Digital Underground

In January 1991 Shakur debuted under the stage name 2Pac on Digital Underground, under a new record label, Interscope Records, on the group’s January 1991 single «Same Song». The song was featured on the soundtrack of the 1991 film Nothing but Trouble, starring Dan Aykroyd, John Candy, Chevy Chase, and Demi Moore.[43] The song opened the group’s January 1991 EP titled This Is an EP Release,[43] while Shakur appeared in the music video.

Shakur’s early days with Digital Underground made him acquainted with Randy «Stretch» Walker, who along with his brother, dubbed Majesty, and a friend debuted with an EP as a rap group and production team, Live Squad, in the Queens, New York.[51] Stretch was featured on a track of the Digital Underground’s 1991 album Sons of the P. Becoming fast friends, Shakur and Stretch recorded and performed together often.[51]

2Pacalypse Now

Shakur’s debut album, 2Pacalypse Now—alluding to the 1979 film Apocalypse Now—arrived in November 1991. Some prominent rappers—like Nas, Eminem, Game, and Talib Kweli—cite it as an inspiration.[52] Aside from «If My Homie Calls», the singles «Trapped» and «Brenda’s Got a Baby» poetically depict individual struggles under socioeconomic disadvantage.[53]

US Vice President Dan Quayle said, «There’s no reason for a record like this to be released. It has no place in our society.» Tupac, finding himself misunderstood,[34] explained, in part;

«I just wanted to rap about things that affected young Black males. When I said that, I didn’t know that I was gonna tie myself down to just take all the blunts and hits for all the young Black males, to be the media’s kicking post for young Black males.»[54][55]

In any case, 2Pacalypse Now was certified Gold, half a million copies sold. The album addresses urban Black concerns said to remain relevant to the present day.[43]

Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z…

Shakur’s second album, Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z…, was released in February 1993.[56] A critical and commercial advance, it debuted at No. 24 on the pop albums chart, the Billboard 200.[57] An overall more hardcore album, it emphasizes Tupac’s sociopolitical views, and has a metallic production quality. The song «Last Wordz» features Ice Cube, co-writer of N.W.A’s «Fuck tha Police», who in his own solo albums had newly gone militantly political, and gangsta rapper Ice-T, who in June 1992 had sparked controversy with his band Body Count’s track «Cop Killer».[56]

In its vinyl release, side A, tracks 1 to 8, is labeled the «Black Side», while side B, tracks 9 to 16, is the «Dark Side».[citation needed] Nonetheless, the album carries the single «I Get Around», a party anthem featuring Digital Underground’s Shock G and Money-B, which became Shakur’s breakthrough, reaching No. 11 on the pop singles chart, the Billboard Hot 100.[57] And it carries the optimistic compassion of another hit, «Keep Ya Head Up», an anthem for women’s empowerment.[58] The album was certified Platinum, with a million copies sold. As of 2004, among Shakur albums, including posthumous and compilation albums, Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z… was 10th in sales at about 1,366,000 copies.[59]

Thug Life

The test pressing single for «Dear Mama»: the Platinum single is among the top-ranked songs in hip-hop history.

In late 1993, Shakur formed the group Thug Life with Tyrus «Big Syke» Himes, Diron «Macadoshis» Rivers, his stepbrother Mopreme Shakur, and Walter «Rated R» Burns.[60] Thug Life released its only album, Thug Life: Volume 1, on October 11, 1994, which is certified Gold. It carries the single «Pour Out a Little Liquor», produced by Johnny «J» Jackson, who would also produce much of Shakur’s album All Eyez on Me. Usually, Thug Life performed live without Tupac.[61]

The track also appears on the 1994 film Above the Rim‘s soundtrack. Due to gangsta rap being under heavy criticism at the time, the album’s original version was scrapped, and the album redone with mostly new tracks. Still, along with Stretch, Tupac would perform the first planned single, «Out on Bail», which was never released, at the 1994 Source Awards.[62][unreliable source?]

The Notorious B.I.G.and Junior M.A.F.I.A.

In 1993, while visiting Los Angeles, the Notorious B.I.G. asked a local drug dealer to introduce him to Shakur and they quickly became friends. The pair would socialize when Shakur went to New York or B.I.G. to Los Angeles.[63] During this period, at his own live shows, Shakur would call B.I.G. onto stage to rap with him and Stretch.[63] Together, they recorded the songs «Runnin’ from tha Police» and «House of Pain».

Reportedly, B.I.G. asked Shakur to manage him, whereupon Shakur advised him that Sean Combs would make him a star.[63] Yet in the meantime, Shakur’s lifestyle was comparatively lavish to B.I.G. who had not yet established himself.[63] Shakur welcomed B.I.G. to join his side group Thug Life, but he would instead form his own side group, the Junior M.A.F.I.A., with his Brooklyn friends Lil’ Cease and Lil’ Kim. Shakur had a falling out with B.I.G. after he was shot at Quad Studios in 1994.[64]

Me Against the World

Shakur’s third album, Me Against the World, was released while he was incarcerated in March 1995.[65] It is now hailed as his magnum opus, and commonly ranks among the greatest, most influential rap albums.[65] The album debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 and sold 240,000 copies in its first week, setting a then record for highest first-week sales for a solo male rapper.[66][67]

The lead single, «Dear Mama», was released in February 1995 with «Old School» as the B-side.[68] It is the album’s most successful single, topping the Hot Rap Singles chart, and peaking at No. 9 on the Billboard Hot 100.[6] In July, it was certified Platinum.[69] It ranked No. 51 on the year-end charts. The second single, «So Many Tears», was released in June 1995,[70] reaching No. 6 on the Hot Rap Singles chart and No. 44 on Hot 100.[6] The final single, «Temptations», was released in August 1995.[71] It reached No. 68 on the Hot 100, No. 35 on the Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Singles & Tracks, and No. 13 on the Hot Rap Singles.[6] Several celebrities showed their support for Shakur by appearing in the music video for «Temptations.»[72]

Shakur won best rap album at the 1996 Soul Train Music Awards.[73] In 2001, it ranked 4th among his total albums in sales, with about 3 million copies sold in the US.[74]

All Eyez on Me

While Shakur was imprisoned in 1995, his mother was about to lose her house. Shakur had his wife Keisha Morris contact Death Row Records founder Suge Knight in Los Angeles.[63] Reportedly, Shakur’s mother promptly received $15,000.[63] After an August visit to Clinton Correctional Facility in northern New York state, Knight traveled southward to New York City to attend the 2nd Annual Source Awards ceremony. Meanwhile, an East Coast–West Coast hip hop rivalry was brewing between Death Row and Bad Boy Records.[75] In October 1995, Knight visited Shakur in prison again and posted $1.4 million bond.[76] Shakur returned to Los Angeles and joined Death Row with the appeal of his December 1994 conviction pending.[76]

Shakur’s fourth album, All Eyez on Me, arrived on February 13, 1996. It was rap’s first double album—meeting two of the three albums due in Shakur’s contract with Death Row—and bore five singles.[77] The album shows Shakur rapping about the gangsta lifestyle, leaving behind his previous political messages. With standout production, the album has more party tracks and often a triumphant tone.[6] Music journalist Kevin Powell noted that Shakur, once released from prison, became more aggressive, and «seemed like a completely transformed person».[78]

As Shakur’s second album to hit No. 1 on both the Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart and the pop albums chart, the Billboard 200,[6] it sold 566,000 copies in its first week and was it was certified 5× Multi-Platinum in April.[79] The singles «How Do U Want It» and «California Love» reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100.[80] Death Row released Shakur’s diss track «Hit ‘Em Up» as the non-album B-side to «How Do U Want It.» In this venomous tirade, the proclaimed «Bad Boy killer» threatens violent payback on all things Bad Boy — B.I.G., Sean Combs, Junior M.A.F.I.A., the company — and on any in the East Coast rap scene, like rap duo Mobb Deep and rapper Chino XL, who allegedly had commented against Shakur about the dispute.[81]

All Eyez on Me won R&B/Soul or Rap Album of the Year at the 1997 Soul Train Music Awards.[82] At the 1997 American Music Awards, Shakur won Favorite Rap/Hip-Hop Artist.[83] The album was certified 9× Multi-Platinum in June 1998,[84] and 10× in July 2014.[85]

Posthumous albums

At the time of his death, a fifth and final solo album was already finished, The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory, under the stage name Makaveli. It had been recorded in one week in August 1996 and released that year.[86][87] The lyrics were written and recorded in three days, and mixing took another four days. In 2005, MTV.com ranked The 7 Day Theory at No. 9 among hip hop’s greatest albums ever,[88] and by 2006 a classic album.[89] Its singular poignance, through hurt and rage, contemplation and vendetta, resonate with many fans.[90]

According to George «Papa G» Pryce, Death Row Records’ then director of public relations, the album was meant to be «underground», and was not intended for release before the artist was murdered.[91][unreliable source?] It peaked at No. 1 on Billboard‘s Top R&B/Hip-Hop Albums chart and on the Billboard 200,[92] with the second-highest debut-week sales total of any album that year.[93] On June 15, 1999, it was certified 4× Multi-Platinum.[94]

Later posthumous albums are archival productions, these albums are:

- R U Still Down? (1997)

- Greatest Hits (1998)

- Still I Rise (1999)

- Until the End of Time (2001)

- Better Dayz (2002)

- Loyal to the Game (2004)

- Pac’s Life (2006)[95]

Film career

Shakur’s first film appearance was in the 1991 film Nothing but Trouble, a cameo by the Digital Underground. In 1992, he starred in Juice, where he plays the fictional Roland Bishop, a militant and haunting individual. Rolling Stone‘s Peter Travers calls him «the film’s most magnetic figure».[96]

In 1993, Shakur starred alongside Janet Jackson in John Singleton’s romance film, Poetic Justice.[97] Singleton later fired Shakur from the 1995 film Higher Learning because the studio would not finance the film following his arrest.[98][99] For the lead role in the eventual 2001 film Baby Boy, a role played by Tyrese Gibson, Singleton originally had Shakur in mind.[100] Ultimately, the set design includes a Shakur mural in the protagonist’s bedroom, and the film’s score includes Shakur’s song «Hail Mary».[101]

Director Allen Hughes had cast Shakur as Sharif in the 1993 film Menace II Society, but replaced him once Shakur assaulted him on set due to a discrepancy with the script. Nonetheless, in 2013, Hughes appraises that Shakur would have outshone the other actors «because he was bigger than the movie».[102]

Shakur played a gangster called Birdie in the 1994 film Above the Rim.[103] By some accounts, that character had been modeled after former New York drug dealer Jacques «Haitian Jack» Agnant,[104] who managed and promoted rappers.[105] Shakur was introduced to him at a Queens nightclub.[63] Reportedly, B.I.G. advised Shakur to avoid him, but Shakur disregarded the warning.[63] Through Haitian Jack, Shakur met James «Jimmy Henchman» Rosemond, also a drug dealer who doubled as music manager.[104]

Soon after Shakur’s death, three more films starring him were released, Bullet (1996), Gridlock’d (1997), and Gang Related (1997).[106][107]

Personal life

In his 1995 interview with Vibe magazine, Shakur listed Jada Pinkett, Jasmine Guy, Treach and Mickey Rourke among the people who were looking out for him while he was in prison.[98] Shakur also mentioned that Madonna was a supportive friend.[98] Madonna later revealed that they had dated in 1994.[108][109]

Shakur met Jada Pinkett while attending the Baltimore School for the Arts.[110] She appeared in his music videos «Keep Ya Head Up» and «Temptations.»[111][72] She also came up with the concept for his «California Love» music video and had intended to direct it, but she removed herself from the project.[112] In 1995, Pinkett contributed $100,000 towards Shakur’s bail as he awaited an appeal on his sexual abuse conviction.[113] Speaking about Pinkett, Shakur stated: «Jada is my heart. She will be my friend for my whole life»; and Pinkett said he was «one of my best friends. He was like a brother. It was beyond friendship for us. The type of relationship we had, you only get that once in a lifetime.»[114]

After Shakur was shot in 1994, he recuperated at Jasmine Guy’s home.[115] They had met during his guest appearance on the sitcom A Different World in 1993.[115] Guy appeared in his music video «Temptations» and later wrote his mother’s 2004 biography, Afeni Shakur: Evolution of a Revolutionary.[116][72]

Shakur befriended Treach when they were both roadies on Public Enemy’s tour in 1990.[117] He made a cameo in Naughty by Nature’s music video «Uptown Anthem» in 1992.[118] Treach collaborated with Shakur on his song «5 Deadly Venomz» and appeared in his music video «Temptations.»[72] Treach was also a speaker at a public memorial service for Shakur in 1996.[119]

Shakur and Mickey Rourke formed a bond while filming the movie Bullet in 1994.[120] Rourke recalled that Shakur «was there for me during some very hard times.»[121]

Shakur had friendships with other celebrities, including Mike Tyson[122] Chuck D,[123] Jim Carrey,[124] and Alanis Morissette. In April 1996, Shakur said that he, Morrissette, Snoop Dogg, and Suge Knight were planning to open a restaurant together.[125][126]

On April 29, 1995, Shakur married his then girlfriend Keisha Morris, a pre-law student.[127][128] Their marriage was annulled ten months later.[129]

In a 1993 interview published in The Source, Shakur criticized record producer Quincy Jones for his interracial marriage to actress Peggy Lipton.[130] Their daughter Rashida Jones responded with an irate open letter.[131] Shakur later apologized to her sister Kidada Jones, who he began dating in 1996.[132] Shakur and Jones attended Men’s Fashion Week in Milan and walked the runway together for a Versace fashion show.[133] Jones was at their hotel in Las Vegas when Shakur was shot.[134]

Legal issues

Sexual assault case, prison sentence, appeal and release

In November 1993, Shakur and two other men were charged in New York with sodomizing a woman in Shakur’s hotel room. The woman, Ayanna Jackson, alleged that after she performed oral sex on Shakur at the public dance floor of a Manhattan nightclub, she went to his hotel room a later day, when Shakur, record executive Jacques «Haitian Jack» Agnant, Shakur’s road manager Charles Fuller and an unidentified fourth man apprehended forced her to perform non-consensual oral sex on each of them.[135][136] Shakur was also charged with illegal possession of a firearm as two guns were found in the hotel room.[137] Interviewed on The Arsenio Hall Show, Shakur said he was hurt that «a woman would accuse me of taking something from her», as he had been raised in a female household and surrounded by women his whole life.[138]

On December 1, 1994, Shakur was acquitted of three counts of sodomy and the associated gun charges, but convicted of two counts of first-degree sexual abuse for «forcibly touching the woman’s buttocks» in his hotel room.[135][34] Jurors have said the lack of evidence stymied a sodomy conviction.[139]

In February 1995, he was sentenced to 18 months to 4+1⁄2 years in prison by a judge who decried «an act of brutal violence against a helpless woman».[137][140] Shakur’s lawyer characterized the sentence as «out of line» with the groping conviction and the setting of bail at $3 million as «inhumane». Shakur’s accuser later filed a civil suit against Shakur seeking $10 million for punitive damages which was subsequently settled.[141][142]

After Shakur had been convicted of sexual abuse, Jacques Agnant’s case was separated and closed via misdemeanor plea without incarceration.[63][143] A. J. Benza reported in New York Daily News Shakur’s new disdain for Agnant who Shakur theorized had set him up with the case.[63][104] Shakur reportedly believed his accuser was connected to and had sexual relations with Agnant and James Rosemond behind his 1994 Quad Studios shooting.[144]

Shakur began serving his prison sentence on sexual abuse charges at Clinton Correctional Facility on February 14, 1995; he also spent a few months recuperating at Rikers Island.[145] While imprisoned, he began reading again, which he had been unable to do as his career progressed due to his marijuana and alcohol habits. Works such as The Prince by Italian philosopher Niccolò Machiavelli and The Art of War by Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu sparked Shakur’s interest in philosophy, philosophy of war and military strategy.[146] On April 4, 1995, Shakur married his girlfriend Keisha Morris; the marriage was later annulled.[147] While in prison, Shakur exchanged letters with celebrities such as Jim Carrey and Tony Danza among others.[148][149] He was also visited by Al Sharpton, who helped Shakur get released from solitary confinement.[150]

By October 1995, pending judicial appeal, Shakur was incarcerated in New York.[113] On October 12, he bonded out of the maximum security Dannemora Clinton Correctional Facility in the process of appealing his conviction,[34] once Suge Knight, CEO of Death Row Records, arranged for posting of his $1.4 million bond.[47]

1993 shooting in Atlanta

On October 31, 1993, Shakur was arrested in Atlanta for shooting two off-duty police officers, brothers Mark Whitwell and Scott Whitwell.[151] The Atlanta police claimed the shooting occurred after the brothers were almost struck by a car carrying Shakur while they were crossing the street with their wives.[152] As they argued with the driver, Shakur’s car pulled up and he shot the Whitwells in the buttocks and the abdomen.[153][154] However, there are conflicting accounts that the Whitwells were harassing a black motorist and uttered racial slurs.[153][152] According to some witnesses, Shakur and his entourage had fired in self-defense as Mark Whitwell shot at them first.[139]

Shakur was charged with two counts of aggravated assault.[151] Mark Whitwell was charged with firing at Shakur’s car and later with making false statements to investigators. Scott Whitwell admitted to possessing a gun he had taken from a Henry County police evidence room.[153] Prosecutors ultimately dropped all charges against both parties.[154] Mark Whitwell resigned from the force seven months after the shooting.[139] Both brothers filed civil suits against Shakur; Mark Whitwell’s suit was settled out of court, while Scott Whitwell’s $2 million lawsuit resulted in a default judgment entered against the rapper’s estate in 1998.[154]

1994 Quad Studios shooting

On November 30, 1994, while in New York recording verses for a mixtape of Ron G, Shakur was repeatedly distracted by his beeper.[155] Music manager James «Jimmy Henchman» Rosemond, reportedly offered Shakur $7,000 to stop by Quad Studios, in Times Square, that night to record a verse for his client Little Shawn.[63][155] Shakur was unsure, but agreed to the session as he needed the cash to offset legal costs. He arrived with Stretch and one or two others. In the lobby, three men robbed and beat him at gunpoint; Shakur resisted and was shot.[156] Shakur speculated that the shooting had been a set-up.[156][157]

Against doctor’s advice, Shakur checked out of Metropolitan Hospital Center a few hours after surgery and secretly went to the house of the actress Jasmine Guy to recuperate.[115][158] The next day, Shakur arrived at a Manhattan courthouse bandaged in a wheelchair to receive the jury’s verdict for his sexual abuse case.[158] Shakur posted a $25,000 bond and spent the next few weeks being cared for by his mother and a private doctor at Guy’s home.[115] The Fruit of Islam and former members of the Black Panther Party stood guard to protect him.[115]

Setup accusations involving the Notorious B.I.G.

In a 1995 interview with Vibe, Shakur accused Sean Combs,[159] Jimmy Henchman,[156] and the Notorious B.I.G, — who were at Quad Studios at the time — among others, of setting up or being privy to the November 1994 robbery and shooting. Vibe alerted the names of the accused. The accusations were significant to the East-West Coast rivalry in hip-hop; in 1995, months after the robbery, Combs and B.I.G. released the track «Who Shot Ya?», which Shakur took as a mockery of his shooting and thought they could be responsible, so he released a diss song, «Hit ‘Em Up», in which he targeted B.I.G., Combs, their record label, Junior M.A.F.I.A., and at the end of «Hit ‘Em Up», he mentions rivals Mobb Deep and Chino XL.[161][162][163][164][165]

In March 2008, Chuck Philips, in the Los Angeles Times, reported on the 1994 ambush and shooting.[166] The newspaper later retracted the article since it relied partially on FBI documents later discovered forged, supplied by a man convicted of fraud.[167] In June 2011, convicted murderer Dexter Isaac, incarcerated in Brooklyn, issued a confession that he had been one of the gunmen who had robbed and shot Shakur at Henchman’s order.[168][169][170] Philips then named Isaac as one of his own, retracted article’s unnamed sources.[171]

Other criminal or civil cases

1991 Oakland Police Department lawsuit

In October 1991, one month before the release of 2Pacalypse Now, two Oakland Police Department officers stopped Shakur for jaywalking. The officers allegedly asked for his name since it did not sound American, he answered them and they brutalized him scratching his face over the street.[172] Shakur filed a $10 million lawsuit against the Oakland Police Department. The case was settled for about $43,000.[47]

Misdemeanor assault convictions

On April 5, 1993, charged with felonious assault, Shakur allegedly threw a microphone and swung a baseball bat at rapper Chauncey Wynn, of the group M.A.D., at a concert at Michigan State University. Shakur claimed the bat was a part of his show and there was no criminal intent.[173] Nonetheless, on September 14, 1994, Shakur pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor, and was sentenced to 30 days in jail, twenty of them suspended, and ordered to 35 hours of community service.[174][173]

Slated to star as Sharif in the 1993 Hughes Brothers’ film Menace II Society, Shakur was replaced by actor Vonte Sweet after allegedly assaulting one of the film’s directors, Allen Hughes. In early 1994, Shakur served 15 days in jail after being found guilty of the assault.[175][176] The prosecution’s evidence included a Yo! MTV Raps interview where Shakur boasts that he had «beat up the director of Menace II Society«.[177]

Concealed weapon case

In 1994, Shakur was arrested in Los Angeles, when he was stopped by police on suspicion of speeding. Police found a semiautomatic pistol in the car, a felony offense because a prior conviction in 1993 in Los Angeles for carrying a concealed firearm.[178] On April 4, 1996, Shakur was sentenced to 120 days in jail for violating his release terms and failing to appear for a road cleanup job,[179] but was allowed to remain free awaiting appeal. On June 7, his sentence was deferred via appeals pending in other cases.[180]

1995 wrongful death suit

On August 22, 1992, in Marin City, Shakur performed outdoors at a festival. For about an hour after the performance, he signed autographs and posed for photos. A conflict broke out and Shakur allegedly drew a legally carried Colt Mustang but dropped it on the ground. Shakur claimed that someone with him then picked it up when it accidentally discharged.[181][182]

About 100 yards (90 meters) away in a schoolyard, Qa’id Walker-Teal, a boy aged 6 on his bicycle, was fatally shot in the forehead. Police matched the bullet to a .38-caliber pistol registered to Shakur. His stepbrother Maurice Harding was arrested in suspicion of having fired the gun, but no charges were filed. Lack of witnesses stymied prosecution. In 1995, Qa’id’s mother filed a wrongful death suit against Shakur, which was settled for about $300,000 to $500,000.[181][182]

C. Delores Tucker lawsuit

Civil rights activist and fierce rap critic C. Delores Tucker sued Shakur’s estate in federal court, claiming that lyrics in «How Do U Want It» and «Wonda Why They Call U Bitch» inflicted emotional distress, were slanderous, and invaded her privacy.[183] The case was later dismissed.[184]

Death

On the night of September 7, 1996, Shakur was in Las Vegas, Nevada, to celebrate his business partner Tracy Danielle Robinson’s birthday[185] and attended the Bruce Seldon vs. Mike Tyson boxing match with Suge Knight at the MGM Grand. Afterward in the lobby, someone in their group spotted Orlando «Baby Lane» Anderson, an alleged Southside Compton Crip, whom the individual accused of having recently tried to snatch his neck chain with a Death Row Records medallion in a shopping mall. The hotel’s surveillance footage shows the ensuing assault on Anderson. Shakur soon stopped by his hotel room and then headed with Knight to his Death Row nightclub, Club 662, in a black BMW 750iL sedan, part of a larger convoy.[186]

At about 11 pm on Las Vegas Boulevard, bicycle-mounted police stopped the car for its loud music and lack of license plates. The plates were found in the trunk and the car was released without a ticket.[187] At about 11:15 pm at a stop light, a white, four-door, late-model Cadillac sedan pulled up to the passenger side and an occupant rapidly fired into the car. Shakur was struck four times: once in the arm, once in the thigh, and twice in the chest[188] with one bullet entering his right lung.[189] Shards hit Knight’s head. Frank Alexander, Shakur’s bodyguard, was not in the car at the time. He would say he had been tasked to drive the car of Shakur’s girlfriend, Kidada Jones.[190]

Shakur was taken to the University Medical Center of Southern Nevada where he was heavily sedated and put on life support.[9] In the intensive-care unit on the afternoon of September 13, 1996, Shakur died from internal bleeding.[9] He was pronounced dead at 4:03 pm.[9] The official causes of death are respiratory failure and cardiopulmonary arrest associated with multiple gunshot wounds.[9] Shakur’s body was cremated the next day. Members of the Outlawz, recalling a line in his song «Black Jesus», (although uncertain of the artist’s attempt at a literal meaning chose to interpret the request seriously) smoked some of his body’s ashes after mixing them with marijuana.[191][192]

In 2002, investigative journalist Chuck Philips,[193][194] after a year of work, reported in the Los Angeles Times that Anderson, a Southside Compton Crip, having been attacked by Suge and Shakur’s entourage at the MGM Hotel after the boxing match, had fired the fatal gunshots, but that Las Vegas police had interviewed him only once, briefly, before his death in an unrelated shooting. Philips’s 2002 article also alleges the involvement of Christopher «Notorious B.I.G.» Wallace and several within New York City’s criminal underworld. Both Anderson and Wallace denied involvement, while Wallace offered a confirmed alibi.[195][unreliable source?] Music journalist John Leland, in The New York Times, called the evidence «inconclusive».[196]

In 2011, via the Freedom of Information Act, the FBI released documents related to its investigation which described an extortion scheme by the Jewish Defense League (classified as «a right wing terrorist group» by the FBI[197]) that included making death threats against Shakur and other rappers, but did not indicate a direct connection to his murder.[198][199]

Legacy and remembrance

Shakur is considered one of the most influential rappers of all time.[200][201] He is widely credited as an important figure in hip hop culture, and his prominence in pop culture in general has been noted.[202] Dotdash, formerly About.com, while ranking him fifth among the greatest rappers, nonetheless notes, «Tupac Shakur is the most influential hip-hop artist of all time. Even in death, 2Pac remains a transcendental rap figure.»[203] Yet to some, he was a «father figure» who, said rapper YG, «makes you want to be better—at every level.»[204]

AllMusic’s Stephen Thomas Erlewine described Shakur as «the unlikely martyr of gangsta rap», with Shakur paying the ultimate price of a criminal lifestyle. Shakur was described as one of the top two American rappers in the 1990s, along with Snoop Dogg.[205] The online rap magazine AllHipHop held a 2007 roundtable at which New York rappers Cormega, citing tour experience with New York rap duo Mobb Deep, commented that B.I.G. ran New York, but Shakur ran America.[206]

In 2010, writing Rolling Stone magazine’s entry on Shakur at No. 86 among the «100 greatest artists», New York rapper 50 Cent appraised;

«Every rapper who grew up in the Nineties owes something to Tupac. He didn’t sound like anyone who came before him.»[207]

According to music journalist Chuck Philips, Shakur «had helped elevate rap from a crude street fad to a complex art form, setting the stage for the current global hip-hop phenomenon.»[208] Philips writes, «The slaying silenced one of modern music’s most eloquent voices—a ghetto poet whose tales of urban alienation captivated young people of all races and backgrounds.»[208] Via numerous fans perceiving him, despite his questionable conduct, as a martyr, «the downsizing of martyrdom cheapens its use», Michael Eric Dyson concedes.[209] But Dyson adds, «Some, or even most, of that criticism can be conceded without doing damage to Tupac’s martyrdom in the eyes of those disappointed by more traditional martyrs.»[209]

In 2014, BET explained that «his confounding mixture of ladies’ man, thug, revolutionary and poet has forever altered our perception of what a rapper should look like, sound like and act like. In 50 Cent, Ja Rule, Lil Wayne, newcomers like Freddie Gibbs and even his friend-turned-rival B.I.G., it’s easy to see that Pac is the most copied MC of all time. There are murals bearing his likeness in New York, Brazil, Sierra Leone, Bulgaria and countless other places; he even has statues in Atlanta and Germany. Quite simply, no other rapper has captured the world’s attention the way Tupac did and still does.»[210] More simply, his writings, published after his death, inspired rapper YG to return to school and get his GED.[204] In 2020, former California Senator and current Vice-president Kamala Harris called Shakur the «best rapper alive», which she explained because «West Coast girls think 2Pac lives on».[211][212]

Tupac Amaru Shakur Foundation

In 1997, Shakur’s mother founded the Shakur Family Foundation. Later renamed the Tupac Amaru Shakur Foundation, or TASF, it launched with a stated mission to «provide training and support for students who aspire to enhance their creative talents.» The TASF sponsors essay contests, charity events, a performing arts day camp for teenagers, and undergraduate scholarships. In June 2005, the TASF opened the Tupac Amaru Shakur Center for the Arts, or TASCA, in Stone Mountain, Georgia. It closed in 2015.

Academic appraisal

In 1997, the University of California, Berkeley, offered a course led by a student titled «History 98: Poetry and History of Tupac Shakur».[213] In April 2003, Harvard University cosponsored the symposium «All Eyez on Me: Tupac Shakur and the Search for the Modern Folk Hero».[214] The papers presented cover his ranging influence from entertainment to sociology.[214] Calling him a «Thug Nigga Intellectual», an «organic intellectual»,[215] English scholar Mark Anthony Neal assessed his death as leaving a «leadership void amongst hip-hop artists»,[216] as this «walking contradiction» helps, Neal explained, «make being an intellectual accessible to ordinary people.»[217]

Tracing Shakur’s mythical status, Murray Forman discussed him as «O.G.», or «Ostensibly Gone», with fans, using digital mediums, «resurrecting Tupac as an ethereal life force.»[218] Music scholar Emmett Price, calling him a «Black folk hero», traced his persona to Black American folklore’s tricksters, which, after abolition, evolved into the urban «bad-man». Yet in Shakur’s «terrible sense of urgency», Price identified instead a quest to «unify mind, body, and spirit.»[218]

Multimedia releases

In 2005, Death Row released on DVD, Tupac: Live at the House of Blues, his final recorded live performance, an event on July 4, 1996. In August 2006, Tupac Shakur Legacy, an «interactive biography» by Jamal Joseph, arrived with previously unpublished family photographs, intimate stories, and over 20 detachable copies of his handwritten song lyrics, contracts, scripts, poetry, and other papers. In 2006, the Shakur album Pac’s Life was released and, like the previous, was among the recording industry’s most popular releases.[219] In 2008, his estate made about $15 million.[220]

On April 15, 2012, at the Coachella Music Festival, rappers Snoop Dogg and Dr. Dre joined a Shakur «hologram» (Although the media referred to the technology as a hologram, technically it was a projection created with the Musion Eyeliner),[221][222][223] and, as a partly virtual trio, performed the Shakur songs «Hail Mary» and «2 of Amerikaz Most Wanted».[224][225] There were talks of a tour,[226] but Dre refused.[227] Meanwhile, the Greatest Hits album, released in 1998, and which in 2000 had left the pop albums chart, the Billboard 200, returned to the chart and reached No. 129, while also other Shakur albums and singles drew sales gains.[228]

Film and stage

The documentary film Tupac: Resurrection was released in November 2003. It was nominated for Best Documentary at the 2005 Academy Awards.[229]

In 2014, the play Holler If Ya Hear Me, based on Shakur’s lyrics, played on Broadway, but, among Broadway’s worst-selling musicals in recent years, ran only six weeks.[230] In development since 2013, a Shakur biopic, All Eyez on Me, began filming in Atlanta in December 2015.[231] It was released on June 16, 2017, on Shakur’s 46th birthday,[232] albeit to generally negative reviews.

In August 2019, a docuseries directed by Allen Hughes, Outlaw: The Saga of Afeni and Tupac Shakur, was announced.[233]

Unpublished works

On March 30, 2022, one of Shakur’s earliest pieces of writing, an unpublished booklet of haiku poetry, was auctioned by Sotheby’s estimated at $200,000 to $300,000 and hammered down at $302,400 plus buyer premium.[234] Shakur was 11 years old when he wrote and illustrated the booklet for Jamal Joseph and three other Black Panther Party members while they were incarcerated at Leavenworth Prison. Even at his young age, Shakur’s writing dealt with themes such as black liberation, mass incarceration, race, and masculinity. The booklet features a self-portrait of Shakur sleeping, pen in hand, dreaming of the Black Panthers being freed from prison, and signed with a heart and the phrase “Tupac Shakur, Future Freedom Fighter.»[235]

A dream is lovely.

You drift to another land.

I dream in the night.[236]

Awards and honors

In 2002, Shakur was inducted into the Hip-Hop Hall of Fame. In 2004, Shakur was among the honorees at the first Hip Hop Honors.[237]

In 2006, Shakur’s close friend and classmate Jada Pinkett Smith donated $1 million to their high school alma mater, the Baltimore School for the Arts, and named the new theater in his honor.[238][239] In 2021, Pinkett Smith honored Shakur’s 50th birthday by releasing a never before seen poem she had received from him.[110]

In 2009, drawing praise, the Vatican added «Changes», a 1998 posthumous track, to its online playlist.[240] On June 23, 2010, the Library of Congress added «Dear Mama» to the National Recording Registry, the third rap song.[241][242]

In 2015, the Grammy Museum opened an exhibition dedicated to Shakur.[243]

In his first year of eligibility, Shakur was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on April 7, 2017.[14][244][245]

In January 2022, the exhibition Tupac Shakur: Wake Me When I’m Free opened at The Canvas at L.A. Live in Los Angeles.[246]

Rankings

- 2002: Forbes magazine ranked Shakur at 10th among top-earning dead celebrities.[247]

- 2003: MTV’s viewers voted Shakur the greatest MC.[248]

- 2005: Shakur was voted No.1 on Vibe’s online poll of «Top 10 Best of All Time».[249]

- 2006: MTV staff placed him second on its list of «The Greatest MCs Of All Time».[89]

- 2012: The Source magazine ranked him No. 5 among «The Top 50 Lyricists».[250]

- 2007: the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame placed All Eyez on Me at No. 90 and Me Against the World at No. 170.[251]

- 2010: Rolling Stone magazine placed Shakur at No. 86 among the «100 Greatest Artists».[207]

- 2020: All Eyez on Me was ranked No. 436 on Rolling Stone‘s list of the «500 Greatest Albums Of All Time.»[252]

Discography

- Studio albums

- 2Pacalypse Now (1991)

- Strictly 4 My N.I.G.G.A.Z… (1993)

- Me Against the World (1995)

- All Eyez on Me (1996)

- Posthumous studio albums

- The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory (1996) (as Makaveli)

- R U Still Down? (Remember Me) (1997)

- Until the End of Time (2001)

- Better Dayz (2002)

- Loyal to the Game (2004)

- Pac’s Life (2006)

- Collaboration albums

- This Is an EP Release with Digital Underground (1991)

- Thug Life: Volume 1 with Thug Life (1994)

- Posthumous collaboration album

- Still I Rise with Outlawz (1999)

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | Nothing but Trouble | Himself (in a fictional context) | Brief appearance as part of the group Digital Underground |

| 1992 | Juice | Roland Bishop | First starring role |

| 1993 | Poetic Justice | Lucky | Co-starred with Janet Jackson |

| 1993 | A Different World | Piccolo | Episode: Homie Don’t Ya Know Me? |

| 1993 | In Living Color | Himself | Season 5, Episode: 3 |

| 1994 | Above the Rim | Birdie | Co-starred with Duane Martin. Final film release during his lifetime |

| 1995 | Murder Was the Case: The Movie | Sniper | Uncredited; segment: «Natural Born Killaz» |

| 1996 | Saturday Night Special | Himself (guest host) | 1 episode |

| 1996 | Saturday Night Live | Himself (musical guest) | Episode: «Tom Arnold/Tupac Shakur» |

| 1996 | Bullet | Tank | Released one month after Shakur’s death |

| 1997 | Gridlock’d | Ezekiel «Spoon» Whitmore | Released four months after Shakur’s death |

| 1997 | Gang Related | Detective Jake Rodriguez | Shakur’s last performance in a film |

| 2001 | Baby Boy | Himself | Archive footage |

| 2003 | Tupac: Resurrection | Himself | Archive footage |

| 2009 | Notorious | Himself | Archive footage |

| 2015 | Straight Outta Compton | Himself | Archive footage |

| 2017 | All Eyez on Me | Himself | Archive footage |

Portrayals in film

| Year | Title | Portrayed by | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | Too Legit: The MC Hammer Story | Lamont Bentley | Biographical film about MC Hammer |

| 2009 | Notorious | Anthony Mackie | Biographical film about the Notorious B.I.G. |

| 2015 | Straight Outta Compton | Marcc Rose[253] | Biographical film about N.W.A |

| 2016 | Surviving Compton: Dre, Suge & Michel’le | Adrian Arthur | Biographical film about Michel’le |

| 2017 | All Eyez on Me | Demetrius Shipp, Jr.[254] | Biographical film about Tupac Shakur[255] |

Documentaries

Shakur’s life has been explored in several documentaries, most notably the Academy Award-nominated Tupac: Resurrection (2003).

- 1997: Tupac Shakur: Thug Immortal

- 1997: Tupac Shakur: Words Never Die (TV)

- 2001: Tupac Shakur: Before I Wake…

- 2001: Welcome to Deathrow

- 2002: Tupac Shakur: Thug Angel

- 2002: Biggie & Tupac

- 2002: Tha Westside

- 2003: 2Pac 4 Ever

- 2003: Tupac: Resurrection

- 2004: Tupac vs.

- 2004: Tupac: The Hip Hop Genius (TV)

- 2006: So Many Years, So Many Tears

- 2015: Murder Rap: Inside the Biggie and Tupac Murders

- 2017: Who killed Tupac?

- 2017: Who Shot Biggie & Tupac?

- 2018: Unsolved: Murders of Biggie and Tupac?

- 2021: The Life & Death of Tupac Shakur[256]

See also

- List of best-selling music artists

- List of best-selling music artists in the United States

- List of murdered hip hop musicians

- List of number-one albums (United States)

- List of number-one hits (United States)

- List of awards and nominations received by Tupac Shakur

- List of artists who reached number one in the United States

Notes

References

- ^ Okwerekwu, Ike (May 5, 2019). «Tupac: The Greatest Inspirational Hip Hop Artist». Music For Inspiration. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ «8 Ways Tupac Shakur Changed the World». Rolling Stone. September 13, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- ^ Tupac Shakur – Thug Angel (The Life of an Outlaw). 2002.

- ^ Alexander, Leslie M.; Rucker, Walter C., eds. (February 28, 2010). Encyclopedia of African American History. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 254–257. ISBN 9781851097692.

- ^ Edwards, Paul (2009). How to Rap: The Art & Science of the Hip-Hop MC. Chicago Review Press. p. 330.

- ^ a b c d e f Huey, Steve (n.d.). «2Pac – All Eyez on Me«. AllMusic. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ Jay-Z (2011). Bailey, Julius (ed.). Essays on Hip Hop’s Philosopher King. McFarland & Company. p. 55. ISBN 978-0786463299.

- ^ Planas, Antonio (April 7, 2011). «FBI outlines parallels in Notorious B.I.G., Tupac slayings». Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on April 11, 2011. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Koch, Ed (October 24, 1997). «Tupac Shakur’s Death Certificate Details». numberonestars. Las Vegas Sun. Archived from the original on May 23, 2012. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ «2Pac’s ‘Greatest Hits’ album certified Diamond». HYPEBEAST. July 8, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ «No Blasphemy: Why 2Pac’s «The Don Killuminati: The 7 Day Theory» Is Rap’s Greatest Album». HipHopDX. November 5, 2018. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ «The Best Selling Tupac Albums of All Time». 2PacLegacy.net. August 4, 2019. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ «Notorious B.I.G., Tupac Shakur To Be Inducted Into Hip-Hop Hall Of Fame». BET. December 30, 2006. Archived from the original on December 30, 2006. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ a b «Rock and Roll Hall of Fame taps Tupac, Journey, Pearl Jam». USA TODAY. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ «100 Greatest Artists». Rolling Stone. December 3, 2010. Archived from the original on December 6, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2019.

- ^ Hoye, Jacob (2006). Tupac: Resurrection. Atria. p. 30. ISBN 0-7434-7435-X.

- ^ Scott, Cathy (October 2, 1996). «22-year-old arrested in Tupac Shakur killing». Las Vegas Sun. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ «Tupac Coroner’s Report». Cathy Scott. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011. Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- ^ Bass, Debra D. (September 4, 1997). «Book chronicling Shakur murder set to hit stores». Las Vegas Sun. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Walker, Charles F. (February 26, 2014). «Tupac Shakur and Tupac Amaru». Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2019.

- ^ Cline, Sarah. «Colonial and Neocolonial Latin America (1750–1900)» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on July 5, 2010. Retrieved October 14, 2010.

- ^ «Exclusive: Mopreme Shakur Talks Tupac; Rapper’s B-Day Celebrated». AllHipHop. Archived from the original on June 18, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ «Rare Interview With Tupac’s Biological Father». Power 107.5. December 30, 2013. Archived from the original on August 7, 2016.

- ^ Scott, Cathy (2002). The Killing of Tupac Shakur. Las Vegas, Nevada: Huntington Press. ISBN 978-0929712208.

- ^ «Afeni Shakur» (PDF). 2Pac Legacy. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2008. Retrieved April 23, 2008.

- ^ a b Sullivan, Randall (January 3, 2003). LAbyrinth: A Detective Investigates the Murders of Tupac Shakur and Notorious B.I.G., the Implication of Death Row Records’ Suge Knight, and the Origins of the Los Angeles Police Scandal. New York City: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3971-X.

- ^ «Geronimo Pratt: Black Panther leader who spent 27 years in jail for a crime he did not commit». The Independent. October 23, 2011.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (June 3, 2011). «Elmer G. Pratt, Jailed Panther Leader, Dies at 63». The New York Times. Retrieved January 16, 2021.

- ^ Shakur, Assata (1987). An Autobiography of Assata Shakur. Lennox S. Hinds (foreword). Lawrence Hill Books. ISBN 0-88208-221-3.

- ^ Dazed (May 4, 2016). «The colourful life of Tupac’s mother Afeni Shakur». Dazed. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Lewis, John (September 6, 2016). «Tupac Was Here». Baltimore Magazine. Retrieved December 19, 2021.

- ^ King, Jamilah (November 15, 2012). «Art and Activism in Charm City: Five Baltimore Collectives That Are Facing Race». Colorlines. ARC. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2013.

- ^ Case, Wesley (March 31, 2017). «Tupac Shakur in Baltimore: Friends, teachers remember the birth of an artist». The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 1, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Philips, Chuck (October 25, 1995). «Tupac Shakur: ‘I am not a gangster’«. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on September 16, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ^ Tupac’s poem «Jada» appears in his book The Rose That Grew from Concrete, which also includes a poem dedicated to her, «The Tears in Cupid’s Eyes».

- ^ Bastfield, Darrin Keith (2002). Back in the Day: My Life and Times with Tupac Shakur. Da Capo Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-345-44775-3.

- ^ Bastfield 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Golus, Carrie (December 28, 2006). Tupac Shakur. Lerner Publications. ISBN 9780822566090. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ «Happy birthday to our brother and comrade, #TupacShakur! This is his Young Communist League membership card from when he lived in Baltimore, Maryland. #RestInPower #SolidarityForever». Twitter. Communist Party USA. June 17, 2019. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2019.

- ^ Farrar, Jordan (May 13, 2011). «Baltimore students protest cuts». Peoples World. Chicago, Illinois: Long View Publishing Co. Archived from the original on August 18, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- ^ Billet, Alexander (October 15, 2011). «‘And Still I See No Changes’: Tupac’s legacy 15 years on». greenleft.org. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- ^ Bastfield 2002, pp. 67–68.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brown, Preezy (November 12, 2016). «How ‘2Pacalypse Now’ Marked The Birth Of A Rap Revolutionary». Vibe. Archived from the original on March 23, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ «Back 2 the Essence: Friends and Families Reminisce over Hip-hop’s Fallen Sons». Vibe. Vol. 7, no. 8. New York City. October 1999. pp. 100–116 [103]. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ^ Marriott, Michel; Brooke, James; LeDuff, Charlie; Lorch, Donatella (September 16, 1996). «Shots Silence Angry Voice Sharpened by the Streets». The New York Times. pp. A–1. Archived from the original on August 25, 2009. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ In an English class, Tupac wrote the paper «Conquering All Obstacles», which says, in part, «our raps, not the sorry story raps everyone is so tired of. They are about what happens in the real world. Our goal is, have people relate to our raps, making it easier to see what really is happening out there. Even more important, what we may do to better our world» [Cliff Mills, Tupac (New York: Checkmark, 2007)].

- ^ a b c Pareles, Jon (September 14, 1996). «Tupac Shakur, 25, Rap Performer Who Personified Violence, Dies». The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ^ Chung, James (February 25, 2020). «These Were Tupac’s Startling Last Words». SPIN. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ «Leila Steinberg». Assemblies in Motion. Archived from the original on February 13, 2008. Retrieved January 25, 2009.

- ^ Sandy, Candace; Daniels, Dawn Marie (December 8, 2010). How Long Will They Mourn Me?: The Life and Legacy of Tupac Shakur. Random House Publishing Group. p. 15. ISBN 9780307757449.

- ^ a b Jones, Charisse (December 1, 1995). «Rapper slain after chase in Queens». The New York Times. p. B 3. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved May 17, 2020.

- ^ «MTV – They Told Us». MTV. Archived from the original on April 23, 2006. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ^ Vaught, Seneca (Spring 2014). «Tupac’s Law: Incarceration, T.H.U.G.L.I.F.E., and the Crisis of Black Masculinity». Spectrum: A Journal on Black Men. 2 (2): 93–94. doi:10.2979/spectrum.2.2.87. S2CID 144439620. Archived from the original on March 6, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2016.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (September 13, 2012). «Tupac Shakur Interview 1995». The Chuck Philips Post. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ Sami, Yenigun (July 19, 2013). «20 Years Ago, Tupac Broke Through». National Public Radio.com. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved October 30, 2013.

- ^ a b «Revisiting 2Pac’s ‘Strictly 4 My N.*.*.*.*.Z…’ (1993) | Retrospective Tribute». Albumism. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ a b «2Pac – Album chart history». Billboard. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- ^ «The Feminism of Tupac». Evanston Public Library. September 17, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2022.

- ^ «Remebering Tupac: His Musical Legacy and His Top Selling Albums». Atlantapost.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2011. Retrieved March 10, 2012.

- ^ Brown, Jake (2005). Tupac Shakur, (2-Pac) in the Studio: The Studio Years (1989-1996). Amber Books Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-9767735-0-4.

- ^ Thug Life: Vol. 1 (CD). 1994.

- ^ «2Pac – Out On Bail (live 1994)». YouTube. January 8, 2007. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Westhoff, Ben (September 12, 2016). «How Tupac and B.I.G. went from friends to deadly rivals». Vice.com. Archived from the original on August 14, 2020. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ Anderson, Joel (October 30, 2019). «The Moment Tupac and Biggie Went From Friends to Enemies». Slate Magazine. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Bierut, Patrick (March 14, 2021). «‘Me Against The World’: How 2Pac Transcended Hip-Hop’s Trappings». uDiscover Music. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ Ramirez, Erika (April 1, 2015). «Tupac’s ‘Me Against the World’ Topped Billboard 200 20 Years Ago Today: A Retrospective». Billboard. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ «Timeline: 25 Years of Rap Records». BBC News. October 11, 2004. Archived from the original on March 30, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ «Dear Mama (US Single #1) at AllMusic». AllMusic. Archived from the original on October 20, 2010. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ^ «RIAA – Gold & Platinum – May 13, 2009 : Search Results – 2 Pac». RIAA. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved May 14, 2009.

- ^ «So Many Tears (EP) at AllMusic». AllMusic. Retrieved March 22, 2009.

- ^ «Temptations (CD/Cassette Single) at AllMusic». AllMusic. Retrieved March 22, 2009.

- ^ a b c d Hochman, Steve (September 24, 1995). «2Pac’s Pals Turn Out for Tupac-Less Video». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Appleford, Steve (April 1, 1996). «It’s a Soul Train Awards Joy Ride for TLC, D’Angelo». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ «Tupac Month: 2Pac’s Discography». Archived from the original on October 13, 2013. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

- ^ «How the 1995 Source Awards Changed Rap Forever». Complex. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ a b Parker, Derrick; Diehl, Matt (2007). Notorious C.O.P.: The Inside Story of the Tupac, Biggie, and Jam Master Jay Investigations from the NYPD’s First «Hip-Hop Cop». New York: St. Martin’s Griffin. pp. 113–116. ISBN 9781429907781. Archived from the original on September 15, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ XXL Magazine, October 2004, p. 104.

- ^ Reese, Alexis (December 15, 2021). «Tupac Talks Quad Studios Shooting in Kevin Powell Interview». BET. Retrieved December 15, 2021.

- ^ Phillips, Chuck (July 31, 2003). «As Associates Fall, Is ‘Suge’ Knight Next?». Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 24, 2015.

- ^ Corpuz, Kristin (June 16, 2020). «Tupac’s Biggest Billboard Hot 100 Hits». Billboard. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ Williams, Stereo (June 4, 2016). «Tupac’s ‘Hit ‘Em Up’: The Most Savage Diss Track Ever Turns 20». The Daily Beast. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ «Maxwell, Tupac Top Soul Train Awards». E! Online. March 7, 1997. Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. Retrieved December 10, 2011.

- ^ «24th American Music Awards». Rock on the Net. Archived from the original on October 26, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ «RIAA – Gold & Platinum». Riaa.com. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ «RIAA – Gold & Platinum Searchable Database – March 09, 2015». riaa.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ «Music News, Interviews, Pics, and Gossip: Yahoo! Music». Ca.music.yahoo.com. April 20, 2011. Archived from the original on March 27, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ XXL Magazine, October 2003.

- ^ «The Greatest Hip-Hop Albums Of All Time». MTV.com. March 9, 2006. Archived from the original on May 7, 2005. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ a b «The Greatest MCs Of All Time». MTV.com. March 9, 2006. Archived from the original on April 13, 2006. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ XXL Magazine, October 2006.

- ^ «Tupac The Workaholic. (MYCOMEUP.COM)». YouTube. February 11, 2010. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ The Don Killuminati chart peaks on AllMusic.

- ^ «All Eyes on Shakur’s ‘Don Killuminati’«. Los Angeles Times. October 23, 1997. Archived from the original on September 15, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^ «Recording Industry Association of America». RIAA. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- ^

The 2008 fire sustained by University Music Group lost, among archives of hundreds of other artists, some of Tupac’s [Jody Rosen, «Here are hundreds more artists whose tapes were destroyed in the UMG fire» Archived November 23, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times, June 25, 2019].

- ^ «2Pac biography». Alleyezonme.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ Williams, Stereo (February 3, 2019). «John Singleton on That Tupac AIDS Test: ‘That Was a Joke!’«. The Daily Beast. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c Powell, Kevin (February 14, 2021). «Revisit Tupac’s April 1995 Cover Story: ‘READY TO LIVE’«. VIBE.com. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Paine, Jake (December 1, 2017). «Michael Rapaport Reveals Tupac, Leo & More Were Part Of The Original «Higher Learning» Cast (Video)». Ambrosia For Heads. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ Tate, Greg (June 26, 2001). «Sex & Negrocity by Greg Tate». Villagevoice.com. Archived from the original on November 1, 2005. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ «FILM». rapbasement.com. April 10, 2008. Archived from the original on August 25, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ Markman, Rob (May 30, 2013). «Tupac Would Have ‘Outshined’ ‘Menace II Society,’ Director Admits». MTV. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016.

- ^ Tinsley, Justin (March 22, 2019). «A look back at ‘Above the Rim’ on its 25th anniversary». Andscape. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c Rodriguez, Jason (September 2011). «Pit of snakes». XXL Magazine. Archived from the original on February 19, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ Goldberg, Lesley (January 23, 2017). «Haitian Jack hip-hop miniseries in the works (exclusive)». The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved May 20, 2020.

- ^ «Gridlock’d». Entertainment Weekly. January 31, 1997. Archived from the original on March 7, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ «Gang Related». Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 4, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ «Madonna confirms that she once dated Tupac Shakur». NME. March 12, 2015. Archived from the original on August 25, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ Grow, Kory (July 11, 2019). «Tupac’s Private Apology to Madonna Could Be Yours for $100,000». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 20, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2020.

- ^ a b Carras, Christi (June 16, 2021). «To mark Tupac Shakur’s 50th birthday, Jada Pinkett Smith remembers what a poet he was». Los Angeles Times. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Pough, Gwendolyn D. (December 1, 2015). Check It While I Wreck It: Black Womanhood, Hip-Hop Culture, and the Public Sphere. Northeastern University Press. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-55553-854-5.

- ^ McQuillar, Tayannah Lee; Johnson, Fred L. (January 26, 2010). Tupac Shakur: The Life and Times of an American Icon. Hachette Books. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-7867-4593-7.

- ^ a b «Jada Pinkett Gives $100,000 To Help Rapper Tupac Shakur». Jet: 30. February 13, 1995.

- ^ Wallace, Irving (2008). The intimate sex lives of famous people (Rev. ed.). Port Townsend, Washington: Feral House. p. 303. ISBN 978-1932595291. OCLC 646836355.

- ^ a b c d e Anderson, Joel (February 14, 2020). «Slow Burn Season 3, Episode 1: Against the World». Slate Magazine. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ «Nonfiction Book Review: Afeni Shakur: Evolution of a Revolutionary by Jasmine Guy». PublishersWeekly.com. February 1, 2004. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Monjauze, Molly (2008). Tupac remembered. San Francisco Chronicle. p. 69. ISBN 9781932855760. OCLC 181069620.

- ^ Rausch, Andrew J. (April 1, 2011). I Am Hip-Hop: Conversations on the Music and Culture. Scarecrow Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-8108-7792-4.

- ^ Bandini (May 20, 2017). «Treach Flies To L.A. & Wages War To Protect Tupac’s Legacy». Ambrosia For Heads. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ Stratton, David (April 6, 1997). «Bullet». Variety. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ «Mickey Rourke Is Mad About Funkmaster Flex’s Tupac Conspiracy Theory». SPIN. May 21, 2017. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ Meara, Paul (November 4, 2015). «That Time Tupac Visited Mike Tyson in Prison». BET. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016.

- ^ Grow, Kory (June 23, 2014). «Read Tupac Shakur’s Heartfelt Letter to Public Enemy’s Chuck D». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016.

- ^ Smithfield, Brad (February 4, 2017). «Jim Carrey wrote humorous letters to Tupac to cheer him up while in prison». Vintage News. Archived from the original on November 17, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ «2Pac – KMEL 1996 Full Interview with Sway». YouTube. Archived from the original on September 2, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ «What Happened (Interview by Sway)». genius.com. Archived from the original on August 7, 2019. Retrieved August 7, 2019.

- ^ Golus, Carrie (August 1, 2010). Tupac Shakur: Hip-Hop Idol. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7613-5473-4.

- ^ «Tupac’s Ex-Wife Does Interview». Tupac-online.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- ^ «Love is Not Enough: 2Pac’s Ex-Wife, Keisha Morris». XXL. New York City: Townsquare Media. September 15, 2011. Archived from the original on March 14, 2018. Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ Williams, Kam (March 12, 2009). «Rashida Jones: The I Love You, Man Interview». LA Sentinel. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2018.

- ^ Freeman, Hadley (February 14, 2014). «Rashida Jones: ‘There’s more than one way to be a woman and be sexy’«. The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 21, 2016.

- ^ Jones, Quincy (2002). Q: The Autobiography of Quincy Jones. Broadway Books. p. 249. ISBN 978-0-7679-0510-7.

- ^ Alexander, Frank; Cuda, Heidi Siegmund (January 10, 2000). Got Your Back: Protecting Tupac in the World of Gangsta Rap. Macmillan. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-312-24299-2.

- ^ Anson, Robert Sam (March 1997). «To Die Like A Gangsta». Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on May 19, 2018. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Perez-Pena, Richard (December 2, 1994). «Wounded Rapper Gets Mixed Verdict In Sex-Abuse Case». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Gladwell, Malcolm (December 2, 1994). «Rapper Shakur guilty of sex abuse, not guilty of sodomy and gun charges». The Washington Post. Retrieved January 6, 2022.

- ^ a b James, George (February 8, 1995). «Rapper Faces Prison Term For Sex Abuse». The New York Times. p. B1. Archived from the original on April 5, 2014. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ TBTEntGroup on (March 7, 2012). «Tupac Shakur interview with «The Arsenio Hall Show» in 1994 [VIDEO]». Hip-hopvibe.com. Archived from the original on December 21, 2013. Retrieved September 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c «Sweatin’ Bullets: Tupac Shakur Dodges Death but Can’t Beat the Rap». Vibe: 23. February 1995.

- ^ Olan, Helaine (February 8, 1995). «Rapper Shakur Gets Prison for Assault». Los Angeles Times. p. A4.

- ^ Bruck, Connie (June 29, 1997). «The Takedown of Tupac». The New Yorker. Archived from the original on November 7, 2019. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- ^ «Doe v. Shakur (civil case)». Casetext. January 22, 1996.

- ^ Metzler, David (Director) (2017). Who Shot Biggie & Tupac? [interview with «Haitian Jack»]. Interviewed by Soledad O’Brien; Ice-T. USA: Critical Content., premiered on television September 24, 2017, by Fox Broadasting Company.

- ^ «Tupac believed his rape case was connected to his Quad Studios shooting». XXL. June 5, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- ^ «Arrest Warrant extended for Tupac Shakur». Los Angeles Times. January 26, 1995.

- ^ Au, Wagner James (December 11, 1996). «Yo, Niccolo!». Salon. San Francisco, California: Salon Media Group Inc. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved December 31, 2016.

- ^ «Tupac’s Ex-Wife Does Interview». Tupac-online.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved July 24, 2010.

- ^ «Jim Carrey’s Surprising Music Moments, From 2Pac to Kid Cudi». Complex. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ «Tony Danza Talks Friendship With Tupac». TV One. September 21, 2012. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ «AL SHARPTON PLANS TO HELP MEEK THE SAME WAY HE HELPED TUPAC IN JAIL». The Source. November 27, 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Smothers, Ronald (November 2, 1993). «Rapper Charged in Shootings of Off-Duty Officers». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ a b Harrington, Richard (November 3, 1993). «Guns N’ Rappers: 3 Arrested In Shootings». The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c Butler, Rhett (May 28, 2020). «Redo ’93: Tupac Shakur’s Shootout With Police Proves Power To People». The Source. Retrieved December 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c «Shakur’s Estate Hit With Default Claim Over Shooting». MTV News. July 20, 1998. Archived from the original on January 27, 2002. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Rodriguez, Jason (September 2011). «Pit of snakes». XXL Magazine. Archived from the original on February 19, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c Samaha, Albert (October 28, 2013). «James Rosemond, Hip-Hop Manager Tied to Tupac Shooting, Gets Life Sentence for Drug Trafficking». Village Voice. New York City. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved November 25, 2013.

- ^ «Rap Artist Tupac Shakur Shot in Robbery». The New York Times. New York City. November 30, 1994. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Gelder, Lawrence Van (December 3, 1994). «Rapper, Shot and Convicted, Leaves Hospital for Secret Site». The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ Stewart, Alison (March 18, 2008). «What Did Sean ‘Puffy’ Combs Know?». Npr.org. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ «Tupac Shakur Interview 1995 « Chuck Philips PostChuck Philips Post». August 28, 2013. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ «Tupac and Biggie’s battle songs». Los Angeles Times. March 17, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ Rodriguez, Jayson. «Game Manager Jimmy Rosemond Recalls Events The Night Tupac Was Shot, Says Session Was ‘All Business’«. MTV News. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- ^ 2Pac (Ft. Outlawz) – Hit ‘Em Up, retrieved June 1, 2021

- ^ The Notorious B.I.G. – Who Shot Ya?, retrieved June 1, 2021

- ^ Philips, Chuck (June 12, 2012). «James «Jimmy Henchman» Rosemond Implicated Himself in 1994 Tupac Shakur Attack: Court Testimony». Village Voice. Archived from the original on June 29, 2012. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ^ «Times retracts Shakur story». Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. April 7, 2008. Archived from the original on March 4, 2018. Retrieved March 22, 2018.

- ^ Evans, Jennifer (June 21, 2001). «Hip hop talent agent arrested charged with operating drug ring». The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ KTLA News (July 13, 2012). «Convicted Killer Confesses to Shooting West Coast Rapper Tupac Shakur». The Courant. Archived from the original on June 19, 2011. Retrieved September 14, 2013.

- ^ Watkins, Greg (June 15, 2011). «Exclusive: Jimmy Henchman Associate Admits to Role in Robbery/Shooting of Tupac; Apologizes To Pac & B.I.G.’s Mothers». Allhiphop.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2012. Retrieved June 5, 2012.

- ^ «Chuck Philips demands apology on Tupac Shakur». LA Weekly. Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ^ «Remembering the Time Tupac Shakur Sued the Oakland Police for $10 Million». KQED. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- ^ a b «Rapper sentenced for assault». The Argus. November 1, 1994. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ «Rapper Tupac Shakur to face assault charge». Ocala Star-Banner. September 9, 1994. Archived from the original on December 8, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ Sullivan 2003, p. 80.

- ^ «Tupac Shakur Biography». Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on August 25, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ Gonzalez, Victor (May 10, 2012). «TUPAC’S TEMPER: FIVE GREATEST FREAKOUTS, FROM MTV TO JAIL TIME». Miami New Times. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016.

- ^ «Rapper Tupac Shakur charged». UPI. May 6, 1994. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ «Rapper Sentenced for Violating Probation». Sfgate. April 6, 1996. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ «Jail Term Put On Hold For Rapper Tupac Shakur». MTV. June 8, 1996. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ a b «Marin slaying case against rapper opens». San Francisco Chronicle. November 3, 1995. Archived from the original on April 12, 2013.

- ^ a b «Settlement in Rapper’s Trial for Boy’s Death». San Francisco Chronicle. November 8, 1995. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013.

- ^ «Rap critic sues Shakur’s estate for defamation». Los Angeles Times. August 1997.

- ^ «C. Delores Tucker; William Tucker, Her Husbandv.richard Fischbein; Belinda Luscombe; Newsweek Magazine; Johnnie L. Roberts; Time Inc.c. Delores Tucker; William Tucker, Appellants, 237 F.3d 275 (3d Cir. 2001)». Justia Law.

- ^ Miller, Matt; Rahimi, Gobi M. (September 6, 2016). «I Spent Six Days Protecting Tupac on His Deathbed». Esquire. New York City: Hearst Magazines. Archived from the original on January 6, 2019. Retrieved January 18, 2019.

- ^ «September 1996 Shooting and Death». madeira.hccanet.org. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ «Tupac Shakur LV Shooting –». Thugz-network.com. September 7, 1996. Archived from the original on February 7, 2012. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ «Rapper Tupac Shakur Gunned Down». MTV News. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ «Detailed information on the fatal shooting». AllEyezOnMe. Archived from the original on May 14, 2008. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ «Tupac Shakur: Before I Wake». film.com. Archived from the original on October 1, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ «Tupac’s life after death». Smh.com.au. September 13, 2006. Archived from the original on December 25, 2011. Retrieved January 7, 2012.

- ^ O’Neal, Sean (August 30, 2011). «Yes, the Outlawz smoked Tupac’s ashes». The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (September 6, 2002). «Who Killed Tupac Shakur?». Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Archived from the original on November 9, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ Philips, Chuck (September 7, 2002). «Who killed Tupac Shakur?: Part 2». Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Archived from the original on March 18, 2013.

- ^ «Notorious B.I.G.’s Family ‘Outraged’ By Tupac Article». Streetgangs.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2003. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ Leland, John (October 7, 2002). «New Theories Stir Speculation On Rap Deaths». The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- ^ «FBI — Terrorism 2000/2001». Fbi.gov. Archived from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ «Unsealed FBI Report on Tupac Shakur». Vault.fbi.gov. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- ^ «FBI files on Tupac Shakur murder show he received death threats from Jewish gang». Haaretz. Haaretz Service. April 14, 2011. Archived from the original on February 15, 2015. Retrieved February 15, 2015.