|

Turkmenistan Türkmenistan (Turkmen) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Emblem |

|

| Motto: Türkmenistan Bitaraplygyň watanydyr «Turkmenistan is the motherland of Neutrality»[1][2] |

|

| Anthem: Garaşsyz Bitarap Türkmenistanyň Döwlet Gimni «National Anthem of Independent Neutral Turkmenistan» |

|

Location of Turkmenistan (red) |

|

| Capital

and largest city |

Ashgabat 37°58′N 58°20′E / 37.967°N 58.333°E |

| Official languages | Turkmen[3] |

| Ethnic groups

(2012) |

|

| Religion

(2020 ?)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Turkmenistani[5] Turkmen[6] Turkmenian |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic under a totalitarian hereditary dictatorship[7][8] |

|

• President |

Serdar Berdimuhamedow |

|

• Vice President |

Raşit Meredow |

|

• Chairman of the People’s Council |

Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow |

|

• Chairperson of the Assembly |

Gülşat Mämmedowa |

| Legislature | Assembly |

| Independence from the Soviet Union | |

|

• Conquest |

1879 |

|

• Soviet rule |

13 May 1925 |

|

• Declared state sovereignty |

22 August 1990 |

|

• From the Soviet Union |

27 October 1991 |

|

• Recognized |

26 December 1991 |

|

• Current constitution |

18 May 1992 |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

491,210 km2 (189,660 sq mi)[9] (52nd) |

|

• Water |

24,069 km2 (9,293 sq mi) |

|

• Water (%) |

4.9 |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

5,636,011[10] (115th) |

|

• Density |

10.5/km2 (27.2/sq mi) (221st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

$117.7 billion [11] (93nd) |

|

• Per capita |

$18,875[11] (80th) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

$74.4 billion[11] (78th) |

|

• Per capita |

$11,929[11] (68th) |

| Gini (1998) | 40.8 medium |

| HDI (2021) | high · 91st |

| Currency | Manat (TMT) |

| Time zone | UTC+05 (TMT) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +993 |

| ISO 3166 code | TM |

| Internet TLD | .tm |

Turkmenistan ( or ; Turkmen: Türkmenistan, pronounced [tʏɾkmønʏˈθːɑːn][13]) is a country located in Central Asia, bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the south and southwest and the Caspian Sea to the west. Ashgabat is the capital and largest city. The population is about 6 million, the lowest of the Central Asian republics, and Turkmenistan is one of the most sparsely populated nations in Asia.[5][14][6]

Turkmenistan has long served as a thoroughfare for several empires and cultures.[15] Merv is one of the oldest oasis-cities in Central Asia,[16] and was once the biggest city in the world.[17] It was also one of the great cities of the Islamic world and an important stop on the Silk Road. Annexed by the Russian Empire in 1881, Turkmenistan figured prominently in the anti-Bolshevik movement in Central Asia. In 1925, Turkmenistan became a constituent republic of the Soviet Union, the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic (Turkmen SSR); it became independent after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.[5]

Turkmenistan possesses the world’s fifth largest reserves of natural gas.[18] Most of the country is covered by the Karakum Desert. From 1993 to 2017, citizens received government-provided electricity, water and natural gas free of charge.[19]

Turkmenistan is an observer state in the Organisation of Turkic States, the Türksoy community and a member of the United Nations.[20] It is also the only permanent neutral country recognized by the UN General Assembly in Asia.[21]

The country is widely criticized for its poor human rights,[22][23] its treatment of minorities, press and religious freedoms. Since gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Turkmenistan has been ruled by repressive totalitarian regimes: that of President for Life Saparmurat Niyazov (also known as Türkmenbaşy or «Head of the Turkmens») until his death in 2006; Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, who became president in 2007 after winning a non-democratic election (he had been vice-president and then acting president previously); and his son Serdar, who won a subsequent presidential election described by international observers as neither free nor fair, and now shares power with his father.[24][25][8]

The use of the death penalty in the country was suspended in 1999,[26] before being formally abolished in 2008.[3]

Etymology[edit]

The name of Turkmenistan (Turkmen: Türkmenistan) can be divided into two components: the ethnonym Türkmen and the Persian suffix -stan meaning «place of» or «country». The name «Turkmen» comes from Turk, plus the Sogdian suffix -men, meaning «almost Turk», in reference to their status outside the Turkic dynastic mythological system.[27] However, some scholars argue the suffix is an intensifier, changing the meaning of Türkmen to «pure Turks» or «the Turkish Turks.»[28]

Muslim chroniclers like Ibn Kathir suggested that the etymology of Turkmenistan came from the words Türk and Iman (Arabic: إيمان, «faith, belief») in reference to a massive conversion to Islam of two hundred thousand households in the year 971.[29]

Turkmenistan declared its independence from the Soviet Union after the independence referendum in 1991. As a result, the constitutional law was adopted on 27 October of that year and Article 1 established the new name of the state: Turkmenistan (Türkmenistan / Түркменистан).[30]

A common name for the Turkmen SSR was Turkmenia (Russian: Туркмения, romanization: Turkmeniya), used in some reports of the country’s independence.[31]

History[edit]

Historically inhabited by the Indo-Iranians, the written history of Turkmenistan begins with its annexation by the Achaemenid Empire of Ancient Iran. Later, in the 8th century AD, Turkic-speaking Oghuz tribes moved from Mongolia into present-day Central Asia. Part of a powerful confederation of tribes, these Oghuz formed the ethnic basis of the modern Turkmen population.[32] In the 10th century, the name «Turkmen» was first applied to Oghuz groups that accepted Islam and began to occupy present-day Turkmenistan.[32] There they were under the dominion of the Seljuk Empire, which was composed of Oghuz groups living in present-day Iran and Turkmenistan.[32] Oghuz groups in the service of the empire played an important role in the spreading of Turkic culture when they migrated westward into present-day Azerbaijan and eastern Turkey.[32]

In the 12th century, Turkmen and other tribes overthrew the Seljuk Empire.[32] In the next century, the Mongols took over the more northern lands where the Turkmens had settled, scattering the Turkmens southward and contributing to the formation of new tribal groups.[32] The sixteenth and eighteenth centuries saw a series of splits and confederations among the nomadic Turkmen tribes, who remained staunchly independent and inspired fear in their neighbors.[32] By the 16th century, most of those tribes were under the nominal control of two sedentary Uzbek khanates, Khiva and Bukhoro.[32] Turkmen soldiers were an important element of the Uzbek militaries of this period.[32] In the 19th century, raids and rebellions by the Yomud Turkmen group resulted in that group’s dispersal by the Uzbek rulers.[32] In 1855 the Turkmen tribe of Teke led by Gowshut-Khan defeated the invading army of the Khan of Khiva Muhammad Amin Khan[33] and in 1861 the invading Persian army of Nasreddin-Shah.[34]

In the second half of the 19th century, northern Turkmens were the main military and political power in the Khanate of Khiva.[35][36] According to Paul R. Spickard, «Prior to the Russian conquest, the Turkmen were known and feared for their involvement in the Central Asian slave trade.»[37][38]

Russian forces began occupying Turkmen territory late in the 19th century.[32] From their Caspian Sea base at Krasnovodsk (now Türkmenbaşy), the Russians eventually overcame the Uzbek khanates.[32] In 1879, the Russian forces were defeated by the Teke Turkmens during the first attempt to conquer the Ahal area of Turkmenistan.[39] However, in 1881, the last significant resistance in Turkmen territory was crushed at the Battle of Geok Tepe, and shortly thereafter Turkmenistan was annexed, together with adjoining Uzbek territory, into the Russian Empire.[32] In 1916, the Russian Empire’s participation in World War I resonated in Turkmenistan, as an anticonscription revolt swept most of Russian Central Asia.[32] Although the Russian Revolution of 1917 had little direct impact, in the 1920s Turkmen forces joined Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and Uzbeks in the so-called Basmachi Rebellion against the rule of the newly formed Soviet Union.[32] In 1921 the tsarist province of Transcaspia (Russian: Закаспийская область, ‘Transcaspian Oblast’) was renamed Turkmen Oblast (Russian: Туркменская область), and in 1924, the Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic was formed from it.[32][40] By the late 1930s, Soviet reorganization of agriculture had destroyed what remained of the nomadic lifestyle in Turkmenistan, and Moscow controlled political life.[32] The Ashgabat earthquake of 1948 killed over 110,000 people,[41] amounting to two-thirds of the city’s population.

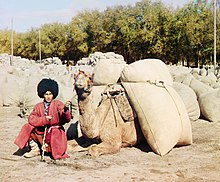

A Turkmen man of Central Asia in traditional clothes. Photo by Prokudin-Gorsky between 1905 and 1915.

During the next half-century, Turkmenistan played its designated economic role within the Soviet Union and remained outside the course of major world events.[32] Even the major liberalization movement that shook Russia in the late 1980s had little impact.[32] However, in 1990, the Supreme Soviet of Turkmenistan declared sovereignty as a nationalist response to perceived exploitation by Moscow.[32] Although Turkmenistan was ill-prepared for independence and then-communist leader Saparmurat Niyazov preferred to preserve the Soviet Union, in October 1991, the fragmentation of that entity forced him to call a national referendum that approved independence.[32] On 26 December 1991, the Soviet Union ceased to exist. Niyazov continued as Turkmenistan’s chief of state, replacing communism with a unique brand of independent nationalism reinforced by a pervasive cult of personality.[32] A 1994 referendum and legislation in 1999 abolished further requirements for the president to stand for re-election (although in 1992 he completely dominated the only presidential election in which he ran, as he was the only candidate and no one else was allowed to run for the office), making him effectively president for life.[32] During his tenure, Niyazov conducted frequent purges of public officials and abolished organizations deemed threatening.[32] Throughout the post-Soviet era, Turkmenistan has taken a neutral position on almost all international issues.[32] Niyazov eschewed membership in regional organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, and in the late 1990s he maintained relations with the Taliban and its chief opponent in Afghanistan, the Northern Alliance.[32] He offered limited support to the military campaign against the Taliban following the 11 September 2001 attacks.[32] In 2002 an alleged assassination attempt against Niyazov led to a new wave of security restrictions, dismissals of government officials, and restrictions placed on the media.[32] Niyazov accused exiled former foreign minister Boris Shikhmuradov of having planned the attack.[32]

Between 2002 and 2004, serious tension arose between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan because of bilateral disputes and Niyazov’s implication that Uzbekistan had a role in the 2002 assassination attempt.[32] In 2004, a series of bilateral treaties restored friendly relations.[32] In the parliamentary elections of December 2004 and January 2005, only Niyazov’s party was represented, and no international monitors participated.[32] In 2005, Niyazov exercised his dictatorial power by closing all hospitals outside Ashgabat and all rural libraries.[32] The year 2006 saw intensification of the trends of arbitrary policy changes, shuffling of top officials, diminishing economic output outside the oil and gas sector, and isolation from regional and world organizations.[32] China was among a very few nations to whom Turkmenistan made significant overtures.[32] The sudden death of Niyazov at the end of 2006 left a complete vacuum of power, as his cult of personality, comparable to the one of eternal president Kim Il-sung of North Korea, had precluded the naming of a successor.[32] Deputy Prime Minister Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, who was named interim head of government, won a non-democratic special presidential election held in early February 2007.[32] His appointment as interim president and subsequent run for president violated the constitution.[42] Berdimuhamedow won two additional non-democratic elections, with approximately 97% of the vote in both 2012[43] and 2017.[44] His son Serdar Berdimuhamedow won a non-democratic snap presidential election in 2022, establishing a political dynasty in Turkmenistan.[45] On 19 March 2022, Serdar Berdimuhamedov was sworn in as Turkmenistan’s new president to succeed his father.[46]

Government[edit]

After over a century of being a part of the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union (including 67 years as a union republic), Turkmenistan declared its independence on 27 October 1991, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[47]

Saparmurat Niyazov, a former official of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, ruled Turkmenistan from 1985, when he became head of the Communist Party of the Turkmen SSR, until his death in 2006. He retained absolute control over the country as President after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. On 28 December 1999, Niyazov was declared President for Life of Turkmenistan by the Mejlis (parliament), which itself had taken office a week earlier in elections that included only candidates hand-picked by President Niyazov. No opposition candidates were allowed.

The former Communist Party, now known as the Democratic Party of Turkmenistan, is the dominant party. The second party, the Party of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs, was established in August 2012, and an agrarian party appeared two years later. Political gatherings are illegal unless government sanctioned.[citation needed] In 2013, the first multi-party parliamentary elections were held in Turkmenistan. Turkmenistan was a one-party state from 1991 to 2012; however, the 2013 elections were widely seen as rigged.[48] In practice, all parties in parliament operate jointly under the direction of the DPT. There are no true opposition parties in the Turkmen parliament.[49]

Legislature[edit]

In September 2020 the Turkmenistan Parliament adopted a constitutional amendment creating an upper chamber and thus making the Parliament bicameral.[50] The upper chamber is named the People’s Council (Turkmen: Halk Maslahaty) and consists of 56 members, 48 of whom are elected and 8 of whom are appointed by the president. Together with the previous unicameral parliament, the 125-seat Mejlis, as the lower chamber, the Parliament is now called the National Council (Turkmen: Milli Geňeş). Elections to the upper chamber were held 28 March 2021.[51][52] Elections to the Mejlis were last held 25 March 2018.[53][54]

Outside observers consider the Turkmen legislature to be a rubber stamp parliament.[53][54][55] The 2018 OSCE election observer mission noted,

The 25 March elections lacked important prerequisites of a genuinely democratic electoral process. The political environment is only nominally pluralist and does not offer voters political alternatives. Exercise of fundamental freedoms is severely curtailed, inhibiting free expression of the voters’ will. Despite measures to demonstrate transparency, the integrity of elections was not ensured, leaving veracity of results in doubt[56]

Judiciary[edit]

The judiciary in Turkmenistan is not independent. Under Articles 71 and 100 of the constitution of Turkmenistan, the president appoints all judges, including the chairperson (chief justice) of the Supreme Court, and may dismiss them with the consent of the Parliament.[57] Outside observers consider the Turkmen legislature to be a rubber stamp parliament,[53][54][55] and thus despite constitutional guarantees of judicial independence under Articles 98 and 99, the judiciary is de facto firmly under presidential control.[58] The chief justice is considered a member of the executive authority of the government and sits on the State Security Council.[59] The U.S. Department of State stated in its 2020-human rights report on Turkmenistan,

Although the law provides for an independent judiciary, the executive controls it, and it is subordinate to the executive. There was no legislative review of the president’s judicial appointments and dismissals. The president had sole authority to dismiss any judge. The judiciary was widely reputed to be corrupt and inefficient.[60]

T-90SA and T-72UMG units.

Many national laws of Turkmenistan have been published online on the Ministry of Justice website.[61]

Military[edit]

The Armed Forces of Turkmenistan (Turkmen: Türkmenistanyň Ýaragly Güýçleri), known informally as the Turkmen National Army (Turkmen: Türkmenistanyň Milli goşun) is the national military of Turkmenistan. It consists of the Ground Forces, the Air Force and Air Defense Forces, Navy, and other independent formations (etc. Border Troops, Internal Troops and National Guard).

Law enforcement[edit]

The national police force in Turkmenistan is mostly governed by the Interior Ministry. The Ministry of National Security (KNB) is the intelligence-gathering asset. The Interior Ministry commands the 25,000 personnel of the national police force directly, while the KNB deals with intelligence and counter-intelligence work.

Politics[edit]

Since the December 2006 death of Niyazov, Turkmenistan’s leadership has made tentative moves to open up the country. His successor, President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow, repealed some of Niyazov’s most idiosyncratic policies, including banning operas and circuses for being «insufficiently Turkmen», though other such rules were later put into place such as the banning of non-white cars.[62][63] In education, Berdimuhamedow’s government increased basic education to ten years from nine years, and higher education was extended from four years to five. Berdimuhamedow was succeeded by his son Serdar in 2022.[64]

The politics of Turkmenistan take place in the framework of a presidential republic, with the President both head of state and head of government. Under Niyazov, Turkmenistan had an one-party system; however, in September 2008, the People’s Council unanimously passed a resolution adopting a new Constitution. The latter resulted in the abolition of the council and a significant increase in the size of Parliament in December 2008 and also permits the formation of multiple political parties.[65]

Corruption[edit]

Transparency International’s 2021 Corruption Perceptions Index placed Turkmenistan in a tie with Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo for 169th place globally, between Chad and Equatorial Guinea, with a score of 19 out of 100.[66]

Opposition media and foreign human rights organizations describe Turkmenistan as suffering from rampant corruption. A non-governmental organization, Crude Accountability, has openly called the economy of Turkmenistan a kleptocracy.[67] Opposition and domestic state-controlled media have described widespread bribery in education and law enforcement.[68][69][70][71] In 2019, the national chief of police, Minister of Internal Affairs Isgender Mulikov, was convicted and imprisoned for corruption.[72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80] In 2020 the deputy prime minister for education and science, Pürli Agamyradow, was dismissed for failure to control bribery in education.[69]

The illegal adoption of abandoned babies in Turkmenistan is blamed on rampant corruption in the agencies involved in the legal adoption process which pushes some parents to a «cheaper and faster» option.[81] One married couple in the eastern Farap district said that they had to provide documents and letters from 40 different agencies to support their adoption application, yet three years later there was still no decision on their bid. Meanwhile, wealthier applicants in Farap received a child for legal adoption within four months after applying because they paid up to 50,000 manats (about $14,300) in bribes.[81]

Foreign relations[edit]

Former president Berdimuhamedov with Russian President Vladimir Putin, 2017

Turkmenistan’s declaration of «permanent neutrality» was formally recognized by the United Nations in 1995.[82] Former President Saparmurat Niyazov stated that the neutrality would prevent Turkmenistan from participating in multi-national defense organizations, but allows military assistance. Its neutral foreign policy has an important place in the country’s constitution. Turkmenistan has diplomatic relations with 139 countries, some of the most important allies being Afghanistan, Armenia, Iran, Pakistan and Russia.[83] Turkmenistan is a member of the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the Economic Cooperation Organization, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, the Islamic Development Bank, Asian Development Bank, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the Food and Agriculture Organization, International Organization of Turkic Culture and observer member of Organisation of Turkic States.

Human rights[edit]

Turkmenistan has been widely criticised for human rights abuses and has imposed severe restrictions on foreign travel for its citizens.[22][23] Discrimination against the country’s ethnic minorities remains in practice. Universities have been encouraged to reject applicants with non-Turkmen surnames, especially ethnic Russians.[84] It is forbidden to teach the customs and language of the Baloch, an ethnic minority.[85] The same happens to Uzbeks, though the Uzbek language was formerly taught in some national schools.[85]

According to Human Rights Watch, «Turkmenistan remains one of the world’s most repressive countries. The country is virtually closed to independent scrutiny, media and religious freedoms are subject to draconian restrictions, and human rights defenders and other activists face the constant threat of government reprisal.»[86]

According to Reporters Without Borders’s 2014 World Press Freedom Index, Turkmenistan had the 3rd worst press freedom conditions in the world (178/180 countries), just before North Korea and Eritrea.[87] It is considered to be one of the «10 Most Censored Countries». Each broadcast under Niyazov began with a pledge that the broadcaster’s tongue will shrivel if he slanders the country, flag, or president.[88]

Religious minorities are discriminated against for conscientious objection and practicing their religion by imprisonment, preventing foreign travel, confiscating copies of Christian literature or defamation.[60][89][90][91] Many detainees who have been arrested for exercising their freedom of religion or belief were tortured and subsequently sentenced to imprisonment, many of them without a court decision.[92][93] Homosexual acts are illegal in Turkmenistan.[94]

Restrictions on free and open communication[edit]

Despite the launch of Turkmenistan’s first communication satellite, the TurkmenSat 1, in April 2015, the Turkmen government banned all satellite dishes in Turkmenistan the same month. The statement issued by the government indicated that all existing satellite dishes would have to be removed or destroyed—despite the communications receiving antennas having been legally installed since 1995—in an effort by the government to fully block access of the population to many «hundreds of independent international media outlets» which are currently accessible in the country only through satellite dishes, including all leading international news channels in different languages. The main target of this campaign is Radio Azatlyk, the Turkmen-language service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (which is run by the U.S. government).[95]

Internet access is filtered and websites to which the government objects are blocked. Blocked websites include opposition news media, YouTube, many social media including Facebook, and encrypted communications applications. Use of virtual private networks to circumvent censorship is prohibited.[96][97][98]

Geography[edit]

Topography of Turkmenistan

At 488,100 km2 (188,500 sq mi), Turkmenistan is the world’s 52nd-largest country. It is slightly smaller than Spain and larger than Cameroon. It lies between latitudes 35° and 43° N, and longitudes 52° and 67° E.

Over 80% of the country is covered by the Karakum Desert. The center of the country is dominated by the Turan Depression and the Karakum Desert. Topographically, Turkmenistan is bounded by the Ustyurt Plateau to the north, the Kopet Dag Range to the south, the Paropamyz Plateau, the Koytendag Range to the east, the Amu Darya Valley, and the Caspian Sea to the west.[99] Turkmenistan includes three tectonic regions, the Epigersin platform region, the Alpine shrinkage region, and the Epiplatform orogenesis region.[99] The Alpine tectonic region is the epicenter of earthquakes in Turkmenistan. Strong earthquakes occurred in the Kopet Dag Range in 1869, 1893, 1895, 1929, 1948, and 1994. The city of Ashgabat and surrounding villages were largely destroyed by the 1948 earthquake.[99]

The Kopet Dag Range, along the southwestern border, reaches 2,912 metres (9,554 feet) at Kuh-e Rizeh (Mount Rizeh).[100]

The Great Balkhan Range in the west of the country (Balkan Province) and the Köýtendag Range on the southeastern border with Uzbekistan (Lebap Province) are the only other significant elevations. The Great Balkhan Range rises to 1,880 metres (6,170 ft) at Mount Arlan[101] and the highest summit in Turkmenistan is Ayrybaba in the Kugitangtau Range – 3,137 metres (10,292 ft).[102] The Kopet Dag mountain range forms most of the border between Turkmenistan and Iran.

Major rivers include the Amu Darya, the Murghab River, the Tejen River, and the Atrek (Etrek) River. Tributaries of the Atrek include the Sumbar River and Chandyr River.

The Turkmen shore along the Caspian Sea is 1,748 kilometres (1,086 mi) long. The Caspian Sea is entirely landlocked, with no natural access to the ocean, although the Volga–Don Canal allows shipping access to and from the Black Sea.

Major cities include Aşgabat, Türkmenbaşy (formerly Krasnovodsk), Balkanabat, Daşoguz, Türkmenabat, and Mary.

Climate, biodiversity and environment[edit]

Turkmenistan map of Köppen climate classification

Turkmenistan is in a temperate desert zone with a dry continental climate. Remote from the open sea, with mountain ranges to the south and southeast, Turkmenistan’s climate is characterized by low precipitation, low cloudiness, and high evaporation. Absence of mountains to the north allows cold Arctic air to penetrate southward to the southerly mountain ranges, which in turn block warm, moist air from the Indian Ocean. Limited winter and spring rains are attributable to moist air from the west, originating in the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea.[99] Winters are mild and dry, with most precipitation falling between January and May. The Kopet Dag Range receives the highest level of precipitation.

The Karakum Desert is one of the driest deserts in the world; some places have an average annual precipitation of only 12 mm (0.47 in). The highest temperature recorded in Ashgabat is 48.0 °C (118.4 °F) and Kerki, an extreme inland city located on the banks of the Amu Darya river, recorded 51.7 °C (125.1 °F) in July 1983, although this value is unofficial. 50.1 °C (122 °F) is the highest temperature recorded at Repetek Reserve, recognized as the highest temperature ever recorded in the whole former Soviet Union.[103] Turkmenistan enjoys 235–240 sunny days per year. The average number of degree days ranges from 4500 to 5000 Celsius, sufficient for production of extra long staple cotton.[99]

Turkmenistan contains seven terrestrial ecoregions: Alai-Western Tian Shan steppe, Kopet Dag woodlands and forest steppe, Badghyz and Karabil semi-desert, Caspian lowland desert, Central Asian riparian woodlands, Central Asian southern desert, and Kopet Dag semi-desert.[104]

Turkmenistan’s greenhouse gas emissions per person (17.5 tCO2e) are considerably higher than the OECD average: due mainly to natural gas seepage from oil and gas exploration.[105]

Administrative divisions[edit]

Turkmenistan is divided into five provinces or welayatlar (singular welayat) and one capital city district. The provinces are subdivided into districts (etraplar, sing. etrap), which may be either counties or cities. According to the Constitution of Turkmenistan (Article 16 in the 2008 Constitution, Article 47 in the 1992 Constitution), some cities may have the status of welaýat (province) or etrap (district).

| Division | ISO 3166-2 | Capital city | Area[106] | Pop (2005)[106] | Key |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashgabat City | TM-S | Ashgabat | 470 km2 (180 sq mi) | 871,500 | |

| Ahal Province | TM-A | Änew | 97,160 km2 (37,510 sq mi) | 939,700 | 1 |

| Balkan Province | TM-B | Balkanabat | 139,270 km2 (53,770 sq mi) | 553,500 | 2 |

| Daşoguz Province | TM-D | Daşoguz | 73,430 km2 (28,350 sq mi) | 1,370,400 | 3 |

| Lebap Province | TM-L | Türkmenabat | 93,730 km2 (36,190 sq mi) | 1,334,500 | 4 |

| Mary Province | TM-M | Mary | 87,150 km2 (33,650 sq mi) | 1,480,400 | 5 |

Economy[edit]

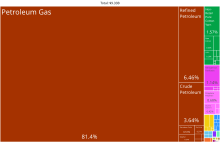

A proportional representation of Turkmenistan exports, 2019

The country possesses the world’s fourth largest reserves of natural gas and substantial oil resources.[107]

Turkmenistan has taken a cautious approach to economic reform, hoping to use gas and cotton sales to sustain its economy. In 2014, the unemployment rate was estimated to be 11%.[5]

Between 1998 and 2002, Turkmenistan suffered from the continued lack of adequate export routes for natural gas and from obligations on extensive short-term external debt. At the same time, however, the value of total exports rose sharply due to increases in international oil and gas prices. The subsequent collapse of both hydrocarbon and cotton prices in 2014 cut revenues from export sales severely, causing Turkmenistan to run trade deficits from 2015 through 2017.[108] Economic prospects in the near future are discouraging because of widespread internal poverty and the burden of foreign debt,[109] coupled with continued low hydrocarbon prices and reduced Chinese purchases of natural gas.[110][111] One reflection of economic stress is the black-market exchange rate for the Turkmen manat, which though officially set at 3.5 manats to the US dollar, reportedly was trading in January 2021 at 32 manats to the dollar.[112]

President Niyazov spent much of the country’s revenue on extensively renovating cities, Ashgabat in particular. Corruption watchdogs voiced particular concern over the management of Turkmenistan’s currency reserves, most of which are held in off-budget funds such as the Foreign Exchange Reserve Fund in the Deutsche Bank in Frankfurt, according to a report released in April 2006 by London-based non-governmental organization Global Witness.

According to a decree of the Peoples’ Council of 14 August 2003,[113] electricity, natural gas, water and salt were to have been subsidized for citizens until 2030. Under implementing regulations, every citizen was entitled to 35 kilowatt hours of electricity and 50 cubic meters of natural gas each month. The state also provided 250 liters (66 gallons) of water per day.[114] As of 1 January 2019, however, all such subsidies were abolished, and payment for utilities was implemented.[115][116][117][118]

Natural gas and export routes[edit]

As of May 2011, the Galkynysh Gas Field was estimated to possess the second-largest volume of gas in the world, after the South Pars field in the Persian Gulf. Reserves at the Galkynysh Gas Field are estimated at 21.2 trillion cubic metres.[119] The Turkmenistan Natural Gas Company (Türkmengaz) controls gas extraction in the country. Gas production is the most dynamic and promising sector of the national economy.[120] In 2009 the government of Turkmenistan began a policy of diversifying export routes for its raw materials.[121]

Prior to 1958 gas production was limited to associated gas from oil wells in western Turkmenistan. In 1958, the first gas wells were drilled at Serhetabat (then Kushky) and at Derweze.[99] Oil and gas fields were discovered in the Central Karakum Desert between 1959 and 1965. In addition to Derweze, these include Takyr, Shyh, Chaljulba, Topjulba, Chemmerli, Atabay, Sakarchage, Atasary, Mydar, Goyun, and Zakli. These fields are located in Jurassic and Cretaceous sediments.[99] The Turkmen gas industry got underway with the opening of the Ojak gas field in 1966. To put this in perspective, associated gas production in Turkmenistan was only 1.157 billion cubic meters in 1965, but by 1970 natural gas production reached 13 billion cubic meters, and by 1989, 90 billion cubic meters. The USSR exported much of this gas to western Europe. Following independence, natural gas extraction fell as Turkmenistan sought export markets but was limited to existing delivery infrastructure under Russian control: Turkmenistan-Russia in two lines (3087 km, originating at Ojak, and another of 2259 km, also originating at Ojak); the Gumdag line (2530 km); and the Shatlyk line (2644 km) to Russia, Ukraine, and the Caucasus.[99] On 1 January 2016, Russia halted natural gas purchases from Turkmenistan after reducing them step by step for the previous years.[122] Russia’s Gazprom announced resumption of purchases in April 2019, but reported volumes remained low compared to previous delivery levels.[123]

In 1997, the Korpeje-Gurtguy natural gas pipeline was built to Iran. It is 140 kilometers in length and was the first gas pipeline to a foreign customer constructed after independence.[99] Turkmenistan’s exports of natural gas to Iran, estimated at 12 bcma, ended on 1 January 2017, when Turkmengaz unilaterally cut off deliveries, citing payment arrears.[124][125]

In December 2009 the first line, Line A, of the Trans-Asia pipeline to China opened, creating a second major market for Turkmen natural gas. By 2015 Turkmenistan was delivering up to 35 billion cubic meters per annum (bcma) to China.[126] China is the largest buyer of gas from Turkmenistan, via three pipelines linking the two countries through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. In 2019, China bought over 30bcm of gas from Turkmenistan,[127][128] making China Turkmenistan’s main external source of revenue.[129]

The East–West pipeline was completed in December 2015, with the intent of delivering up to 30 bcm of natural gas to the Caspian shore for eventual export through a yet-to-be-built Trans-Caspian natural gas pipeline connecting the Belek-1 compressor station in Turkmenistan to Azerbaijan.

The Turkmenistan government continues to pursue construction of the Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India Pipeline, or TAPI.[130] The anticipated cost of the TAPI pipeline is currently estimated at $25 billion. Turkmenistan’s section of the pipeline was started in 2015 and was completed in 2019, though the Afghanistan and Pakistan sections remain under construction.

6 billion dollars worth of methane, a greenhouse gas which causes climate change, was estimated to leak in 2019/20.[131]

Oil[edit]

Oil was known to exist in western Turkmenistan as early as the 18th century. General Aleksey Kuropatkin reported in 1879 that the Cheleken Peninsula had as many as three thousand oil sources.[132] Turkmen settlers in the 19th century extracted oil near the surface and shipped it to Astrakhan by ship and to Iran by camel caravan. Commercial oil drilling began in the 1890s. The oil extraction industry grew with the exploitation of the fields in Cheleken in 1909 (by Branobel) and in Balkanabat in the 1930s. Production leaped ahead with the discovery of the Gumdag field in 1948 and the Goturdepe field in 1959. By 1940 production had reached two million tons per year, by 1960 over four million tons, and by 1970 over 14 million tons. Oil production in 2019 was 9.8 million tons.[99][108]

Oil wells are mainly found in the western lowlands. This area also produces associated natural gas. The main oilfields are Cheleken, Gonurdepe, Nebitdag, Gumdag, Barsagelmez, Guyujyk, Gyzylgum, Ordekli, Gogerendag, Gamyshlyja, Ekerem, Chekishler, Keymir, Ekizek, and Bugdayly. Oil is also produced from offshore wells in the Caspian Sea.[99] Most oil is extracted by the Turkmenistan State Company (Concern) Türkmennebit from fields at Goturdepe, Balkanabat, and on the Cheleken Peninsula near the Caspian Sea, which have a combined estimated reserve of 700 million tons. Much of the oil produced in Turkmenistan is refined in the Türkmenbaşy and Seydi refineries. Some oil is exported by tanker vessel across the Caspian Sea en route to Europe via Baku and Makhachkala.[133][134][135] Foreign firms involved in offshore oil extraction include Eni S.p.A. of Italy, Dragon Oil of the United Arab Emirates, and Petronas of Malaysia.

On 21 January 2021, the governments of Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan signed a memorandum of understanding to develop jointly an oil field in the Caspian Sea that straddles the nations’ border. Known previously as Kyapaz in Azeri and Serdar in Turkmen, the oil field, now called Dostluk («friendship» in both languages), potentially has reserves of up to 60 million tons of oil as well as associated natural gas.[136][137][138]

Energy[edit]

The generators of the Hindukush hydro power plant

Turkmenistan’s first electrical power plant was built in 1909 and went into full operation in 1913. As of 2019 it was still in operation. The original triple-turbine Hindukush hydroelectric plant, built by the Austro-Hungarian company Ganz Works[139] on the Murghab River, was designed to produce 1.2 megawatts at 16.5 kilovolts.[140][141] Until 1957, however, most electrical power in Turkmenistan was produced locally by small diesel generators and diesel-electric locomotives.[141]

In 1957 Soviet authorities created a republic-level directorate for power generation, and in 1966 Turkmenistan entered the first phase of connecting its remote regions to the regional Central Asian electrical grid. By 1979 all rural areas of Turkmenistan were brought on line. Construction of the Mary thermal power plant began in 1969, and by 1987 the eighth and final generator block was completed, bringing the plant to its design capacity of 1.686 gigawatts. In 1998 Turkmenenergo commissioned its first gas-turbine power plant, using GE turbines.[141]

As of 2010 Turkmenistan featured eight major power plants operating on natural gas, in Mary, Ashgabat, Balkanabat, Buzmeyin (suburb of Ashgabat), Dashoguz, Türkmenbaşy, Turkmenabat, and Seydi.[99] As of 2013, Turkmenistan had 10 electrical power plants equipped with 32 turbines, including 14 steam-driven, 15 gas powered, and 3 hydroelectric.[142] Power output in 2011 was 18.27 billion kWh, of which 2.5 billion kWh was exported.[142] Major power generating installations include the Hindukush Hydroelectric Station,[143] which has a rated capacity of 350 megawatts, and the Mary Thermoelectric Power Station,[144] which has a rated capacity of 1,370 megawatts. In 2018, electrical power production totaled more than 21 billion kilowatt-hours.[145]

Since 2013, additional power plants have been constructed in Mary and Ahal province, and Çärjew District of Lebap province. The Mary-3 combined cycle power plant, built by Çalık Holding with GE turbines, commissioned in 2018, produces 1.574 gigawatts of electrical power and is specifically intended to support expanded exports of electricity to Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Zerger power plant built by Sumitomo, Mitsubishi, Hitachi, and Rönesans Holding in Çärjew District has a design capacity of 432 megawatts from three 144-megawatt gas turbines and was commissioned in September 2021.[146] It is also primarily intended for export of electricity. The Ahal power plant, with capacity of 650 megawatts, was constructed to power the city of Ashgabat and in particular the Olympic Village.[147][148][149][150]

Turkmenistan is a net exporter of electrical power to Central Asian republics and southern neighbors. In 2019, total electrical energy generation in Turkmenistan reportedly totaled 22,521.6 million kilowatt-hours (22.52 terawatt-hours).[151]

Agriculture[edit]

Following independence in 1991, Soviet-era collective- and state farms were converted to «farmers associations» (Turkmen: daýhan birleşigi).[99] Virtually all field crops are irrigated due to the aridity of the climate. The top crop in terms of area planted is wheat (761 thousand hectares in 2019), followed by cotton (551 thousand hectares in 2019).[108]

Turkmenistan is the world’s tenth-largest cotton producer.[152] Turkmenistan started producing cotton in the Murghab Valley following conquest of Merv by the Russian Empire in 1884.[153] According to human rights organizations, public sector workers, such as teachers and doctors, are required by the government to pick cotton under the threat of losing their jobs if they refuse.[154]

During the 2020 season, Turkmenistan reportedly produced roughly 1.5 million tons of raw cotton. In 2012, around 7,000 tractors, 5,000 cotton cultivators, 2,200 sowing machines and other machinery, mainly procured from Belarus and the United States, were used. Prior to imposition of a ban on export of raw cotton in October 2018, Turkmenistan exported raw cotton to Russia, Iran, South Korea, United Kingdom, China, Indonesia, Turkey, Ukraine, Singapore and the Baltic states. Beginning in 2019, the Turkmenistan government shifted focus to export of cotton yarn and finished textiles and garments.[155][156][157]

Tourism[edit]

Turkmenistan reported arrival of 14,438 foreign tourists in 2019.[108] Turkmenistan’s international tourism has not grown significantly despite creation of the Awaza tourist zone on the Caspian Sea.[158] Every traveler must obtain a visa before entering Turkmenistan (see Visa policy of Turkmenistan). To obtain a tourist visa, citizens of most countries need visa support from a local travel agency. For tourists visiting Turkmenistan, organized tours exist providing visits to historical sites in and near Daşoguz, Konye-Urgench, Nisa, Ancient Merv, and Mary, as well as beach tours to Avaza and medical tours and holidays in the sanatoria in Mollagara, Bayramaly, Ýylysuw and Archman.[159][160][161]

In January 2022 President Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedow ordered that the fire at the Darvaza gas crater, known informally as the country’s «Gateway to Hell», and one of Turkmenistan’s most popular tourist attractions, should be extinguished.[162] Many believe that the crater formed when a Soviet drilling operation went wrong in 1971, but Canadian explorer George Kourounis examined it in 2013 and discovered that no-one actually knows how it started.[163]

Transportation[edit]

Automobile transport[edit]

Prior to the 1917 Russian Revolution only three automobiles existed in Turkmenistan, all of them foreign models in Ashgabat. No automobile roads existed between settlements. After the revolution, Soviet authorities graded dirt roads to connect Mary and Kushky (Serhetabat), Tejen and Sarahs, Kyzyl-Arvat (Serdar) with Garrygala (Magtymguly) and Chekishler, i.e., with important border crossings. In 1887–1888 the Gaudan Highway (Russian: Гауданское шоссе) was built between Ashgabat and the Persian border at Gaudan Pass, and Persian authorities extended it to Mashhad, allowing for easier commercial relations. Municipal bus service began in Ashgabat in 1925 with five routes, and taxicab service began in 1938 with five vehicles. The road network was extended in the 1970s with construction of republic-level highways connecting Ashgabat and Kazanjyk (Bereket), Ashgabat and Bayramaly, Nebit Dag (Balkanabat) and Krasnovodsk (Türkmenbaşy), Çärjew (Turkmenabat) and Kerki, and Mary and Kushka (Serhetabat).[164]

The primary west–east motor route is the M37 highway linking the Turkmenbashy International Seaport to the Farap border crossing via Ashgabat, Mary, and Turkmenabat. The primary north–south route is the Ashgabat-Dashoguz Automobile Road (Turkmen: Aşgabat-Daşoguz awtomobil ýoly), built in the 2000s. Major international routes include European route E003, European route E60, European route E121, and Asian Highway (AH) routes AH5, AH70, AH75, AH77, and AH78.[165]

A new toll motorway is under construction between Ashgabat and Turkmenabat by «Turkmen Awtoban» company, which will construct the 600-km highway in three phases: Ashgabat-Tejen by December 2020, Tejen-Mary by December 2022 and Mary-Turkmenabat by December 2023. A sister project to link Türkmenbaşy and Ashgabat was suspended when the Turkish contractor, Polimeks, walked away from the project, reportedly because of non-payment.[166]

As of 29 January 2019, the Turkmen Automobile Roads state concern (Turkmen: Türkmenawtoýollary) was subordinated by presidential decree to the Ministry of Construction and Architecture, and responsibility for road construction and maintenance was shifted to provincial and municipal governments.[167][168] Operation of motor coaches (buses) and taxicabs is the responsibility of the Automobile Services Agency (Turkmen: Türkmenawtoulaglary Agentligi) of the Ministry of Industry and Communication.[169]

Air transport[edit]

Air service began in 1927 with a route between Çärjew (Turkmenabat) and Tashauz (Dashoguz), flying German Junkers 13 and Soviet K-4 aircraft, each capable of carrying four passengers. In 1932 an aerodrome was built in Ashgabat on the site of the current Howdan neighborhoods, for both passenger and freight service, the latter mainly to deliver supplies to sulfur mines near Derweze in the Karakum Desert.[170]

Airports serving the major cities of Ashgabat, Dashoguz, Mary, Turkmenabat, and Türkmenbaşy, which are operated by Turkmenistan’s civil aviation authority’s airline, Türkmenhowaýollary, feature scheduled domestic commercial air service.[171][172] Under normal circumstances international scheduled commercial air service is limited to Ashgabat. During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, international flights take off from and land at Turkmenabat, where quarantine facilities have been established.[173][174]

State-owned Turkmenistan Airlines is the only Turkmen air carrier. Turkmenistan Airlines’ passenger fleet is composed of Boeing and Bombardier Aerospace aircraft.[175] Air transport carries more than two thousand passengers daily in the country.[176] Under normal conditions, international flights annually transport over half a million people into and out of Turkmenistan, and Turkmenistan Air operates regular flights to Moscow, London, Frankfurt, Birmingham, Bangkok, Delhi, Abu Dhabi, Amritsar, Kyiv, Lviv, Beijing, Istanbul, Minsk, Almaty, Tashkent, and St. Petersburg.

Small airfields serve industrial sites near other cities, but do not feature scheduled commercial passenger service. Airfields slated for modernization and expansion include those serving Garabogaz, Jebel, and Galaýmor.[177][178][179][180][181] The new Turkmenabat International Airport was commissioned in February 2018.[182] In June 2021, an international airport was opened in Kerki.

Maritime transport[edit]

Workers in the service of Maritime and River Transport of Turkmenistan

Since 1962, the Turkmenbashy International Seaport has operated a passenger ferry to the port of Baku, Azerbaijan as well as rail ferries to other ports on the Caspian Sea (Baku, Aktau). In recent years tanker transport of oil to the ports of Baku and Makhachkala has increased.

In May 2018 construction was completed of a major expansion of the Turkmenbashy seaport.[183][184] Cost of the project was $1.5 billion. The general contractor for the project was Gap Inşaat, a subsidiary of Çalık Holding of Turkey. The expansion added 17 million tons of annual capacity, making total throughput including previously existing facilities of over 25 million tons per year. The international ferry and passenger terminals will be able to serve 300,000 passengers and 75,000 vehicles per year, and the container terminal is designed to handle 400,000 TEU (20-foot container equivalent) per year.[185][186][187]

Railway transport[edit]

Turkmen diesel locomotive

The first rail line in Turkmenistan was built in 1880, from the eastern shore of the Caspian Sea to Mollagara. By October 1881 the line was extended to Kyzyl-Arvat, by 1886 had reached Çärjew. In 1887 a wooden rail bridge was built over the Amu Darya, and the line was continued to Samarkand (1888) and Tashkent (1898).[188] Rail service in Turkmenistan began as part of Imperial Russia’s Trans-Caspian Railway, then of the Central Asian Railway. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the railway network in Turkmenistan was transferred to and operated by the state-owned Türkmendemirýollary. The rail gauge is the same as the Russian (and former Soviet) one-1520 millimeters.

The total length of railways is 3181 km. Only domestic passenger service is available, except for special trains operated by tour operators.[189] The railway carries approximately 5.5 million passengers and moves nearly 24 million tons of freight per year.[108][190][191]

Turkmen Railways is currently constructing a rail line in Afghanistan to connect Serhetabat to Herat.[192] Upon completion, it may connect to the proposed rail line to connect Herat to Khaf, Iran.[193]

Demographics[edit]

The last census to be published was held in 1995. Results of every census since then have been kept secret. Available figures indicate that most of Turkmenistan’s citizens are ethnic Turkmens with sizeable minorities of Uzbeks and Russians. Smaller minorities include Kazakhs, Tatars, Ukrainians, Kurds (native to the Kopet Dagh mountains), Armenians, Azeris, Balochs and Pashtuns. The percentage of ethnic Russians in Turkmenistan dropped from 18.6% in 1939 to 9.5% in 1989. The CIA World Factbook estimated the ethnic composition of Turkmenistan in 2003 as 85% Turkmen, 5% Uzbek, 4% Russian and 6% other.[5] According to official data announced in Ashgabat in February 2001, 91% of the population were Turkmen, 3% were Uzbeks and 2% were Russians. Between 1989 and 2001 the number of Turkmen in Turkmenistan doubled (from 2.5 to 4.9 million), while the number of Russians dropped by two-thirds (from 334,000 to slightly over 100,000).[194][195] As of 2021, the number of Russians in Turkmenistan was estimated at 100,000.[196]

Opposition media reported that some results of the 2012 census had been surreptitiously released, including a total population number of 4,751,120. According to this source, as of 2012 85.6% of the population was ethnically Turkmen, followed by 5.8% ethnic Uzbek and 5.1% ethnic Russian. In contrast, an official Turkmen delegation reported to the UN in January 2015 some different figures on national minorities, including slightly under 9% ethnic Uzbek, 2.2% ethnic Russian, and 0.4% ethnic Kazakh. The 2012 census reportedly counted 58 different nationalities.[197][198][199]

Official population estimates of 6.2 million are likely too high, given known emigration trends.[200] Population growth has been offset by emigration in search of permanent employment.[201] In July 2021 opposition media reported, based on three independent anonymous sources, that the population of Turkmenistan was between 2.7 and 2.8 million.[202]

A once-in-a-decade national census was conducted December 17–27, 2022. Opposition media reported that many people claimed not to have been interviewed by census workers, or that census workers merely telephoned respondents, and did not visit them to count residents.[203][204]

|

Largest cities or towns in Turkmenistan List of cities in Turkmenistan |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||

Ashgabat  Türkmenabat |

1 | Ashgabat | Capital | 947,221 |  Daşoguz |

| 2 | Türkmenabat | Lebap | 279,765 | ||

| 3 | Daşoguz | Daşoguz | 245,872 | ||

| 4 | Mary | Mary | 126,141 | ||

| 5 | Serdar | Balkan | 93,692 | ||

| 6 | Baýramaly | Mary | 91,713 | ||

| 7 | Balkanabat | Balkan | 90,149 | ||

| 8 | Tejen | Ahal | 79,324 | ||

| 9 | Türkmenbaşy | Balkan | 73,803 | ||

| 10 | Magdanly | Lebap | 68,133 |

Migration[edit]

Based on data from receiving countries, MeteoZhurnal estimated that at least 102,346 Turkmenistani citizens emigrated abroad in 2019, 78% of them to Turkey, and 24,206 apparently returned home, for net migration of 77,014.[201] According to leaked results of a 2018 survey, between 2008 and 2018 1,879,413 Turkmenistani citizens emigrated permanently out of an estimated base population of 5.4 million.[205][206]

Turkmen tribes[edit]

The tribal nature of Turkmen society is well documented. The major modern Turkmen tribes are Teke, Yomut, Ersari, Chowdur, Gokleng and Saryk.[207][208] The most numerous are the Teke.[209]

Languages[edit]

Turkmen is the official language of Turkmenistan (per the 1992 Constitution). Since the late 20th century, the government of Turkmenistan has taken steps to distance itself from the Russian language (which has been seen as a soft power tool for Russian interests). The first step in this campaign was the shift to the Latin alphabet in 1993,[210] and Russian lost its status as the language of inter-ethnic communication in 1996.[211] As of 1999 Turkmen was spoken by 72% of the population, Russian by 12% (349,000), Uzbek by 9%[5] (317,000), and other languages by 7% (Kazakh (88,000), Tatar (40,400), Ukrainian (37,118), Azerbaijani (33,000), Armenian (32,000), Northern Kurdish (20,000), Lezgian (10,400), Persian (8,000), Belarusian (5,290), Erzya (3,490), Korean (3,490), Bashkir (2,610), Karakalpak (2,540), Ossetic (1,890), Dargwa (1,600), Lak (1,590), Tajik (1,280), Georgian (1,050), Lithuanian (224), Tabasaran (180), and Dungan).[212]

Religion[edit]

According to the CIA World Factbook, Muslims constitute 93% of the population while 6% of the population are followers of the Eastern Orthodox Church and the remaining 1% religion is reported as non-religious.[5] According to a 2009 Pew Research Center report, 93.1% of Turkmenistan’s population is Muslim.[213]

The first migrants were sent as missionaries and often were adopted as patriarchs of particular clans or tribal groups, thereby becoming their «founders.» Reformulation of communal identity around such figures accounts for one of the highly localized developments of Islamic practice in Turkmenistan.[214]

In the Soviet era, all religious beliefs were attacked by the communist authorities as superstition and «vestiges of the past.» Most religious schooling and religious observance were banned, and the vast majority of mosques were closed. However, since 1990, efforts have been made to regain some of the cultural heritage lost under Soviet rule.[215]

Former president Saparmurat Niyazov ordered that basic Islamic principles be taught in public schools. More religious institutions, including religious schools and mosques, have appeared, many with the support of Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Turkey. Under Niyazov, religious classes were held in both schools and mosques, with instruction in Arabic language, the Qur’an and the hadith, and history of Islam.[216] At present, the only educational institution teaching religion is the theological faculty of Turkmen State University.

President Niyazov wrote his own religious text, published in separate volumes in 2001 and 2004, entitled the Ruhnama («Book of the Soul»). The Turkmenbashy regime required that the book, which formed the basis of the educational system in Turkmenistan, be given equal status with the Quran (mosques were required to display the two books side by side). The book was heavily promoted as part of the former president’s personality cult, and knowledge of the Ruhnama was required even for obtaining a driver’s license.[217] Quotations from the Ruhnama are inscribed on the walls of the Türkmenbaşy Ruhy Mosque, which many Muslims consider sacrilege.[218]

Most Christians in Turkmenistan belong to Eastern Orthodoxy (about 5% of the population).[219] There are 12 Russian Orthodox churches in Turkmenistan, four of which are in Ashgabat.[220] An archpriest resident in Ashgabat leads the Orthodox Church within the country. Until 2007 Turkmenistan fell under the religious jurisdiction of the Russian Orthodox archbishop in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, but since then has been subordinate to the Archbishop of Pyatigorsk and Cherkessia.[221] There are no Russian Orthodox seminaries in Turkmenistan.

There are also small communities of the following denominations: the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Roman Catholic Church, Pentecostal Christians, the Protestant Word of Life Church, the Greater Grace World Outreach Church, the New Apostolic Church, Jehovah’s Witnesses, Jews, and several unaffiliated, nondenominational evangelical Christian groups. In addition, there are small communities of Baháʼís, Baptists, Seventh-day Adventists, and Hare Krishnas.[89]

The history of Baháʼí Faith in Turkmenistan is as old as the religion itself, and Baháʼí communities still exist today.[222] The first Baháʼí House of Worship was built in Ashgabat at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was seized by the Soviets in the 1920s and converted to an art gallery. It was heavily damaged in the earthquake of 1948 and later demolished. The site was converted to a public park.[223]

The Russian Academy of Sciences has identified many instances of syncretic influence of pre-Islamic Turkic belief systems on practice of Islam among Turkmen.[224]

Culture[edit]

Turkmen bakshy – traditional musicians – historically are traveling singers and shamans, acting as healers and spiritual figures, providing music for celebrations of weddings, births, and other important life events.

The Turkmen people have traditionally been nomads and equestrians, and even today after the fall of the USSR attempts to urbanize the Turkmens have not been very successful.[225] They never really formed a coherent nation or ethnic group until they were forged into one by Joseph Stalin in the 1930s. Rather they are divided into clans, and each clan has its own dialect and style of dress.[226] Turkmens are famous for making knotted Turkmen carpets, often mistakenly called Bukhara rugs in the West. These are elaborate and colorful hand-knotted carpets, and these too help indicate the distinctions among the various Turkmen clans. Ethnic groups throughout the region build yurts, circular houses with dome roofs, made of a wooden frame covered in felt from the hides of sheep or other livestock. Horses are an essential ingredient of recreational activities in most of the region, in such games as horseback fighting, in which riders grapple to topple each other from their horses; horse racing.[227]

Turkmen men wear traditional telpek hats, which are large black or white sheepskin hats. Traditional dress for men consists of these high, shaggy sheepskin hats and red robes over white shirts. Women wear long sack-dresses over narrow trousers (the pants are trimmed with a band of embroidery at the ankle). Female headdresses usually consist of silver jewelry. Bracelets and brooches are set with semi-precious stones.

Mass media[edit]

Newspapers and monthly magazines are published by state-controlled media outlets, primarily in Turkmen. The daily official newspaper is published in both Turkmen (Türkmenistan)[228] and Russian (Нейтральный Туркменистан).[229] Two online news portals repeat official content, Turkmenportal and Parahat.info,[230] in addition to the official «Golden Age» (Turkmen: Altyn Asyr, Russian: Золотой век) news website,[231] which is available in Turkmen, Russian, and English. Two Ashgabat-based private news organizations, Infoabad[232] and Arzuw,[233] offer online content.

Articles published by the state-controlled newspapers are heavily censored and written to glorify the state and its leader. Uncensored press coverage specific to Turkmenistan is provided only by news organizations located outside Turkmenistan: Azatlyk Radiosy,[234] the Turkmen service of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty based in Prague; Chronicles of Turkmenistan,[235] the Vienna-based outlet of the Turkmen Initiative for Human Rights; Turkmen.news,[236] previously known as Alternative News of Turkmenistan, based in the Netherlands; and Gündogar.[237] In addition, Mediazona Central Asia,[238] Eurasianet[239] and Central Asia News[240] provide some reporting on events in Turkmenistan.

Turkmenistan currently broadcasts 7 national TV channels via satellite. They are Altyn Asyr, Ýaşlyk, Miras, Turkmenistan (in 7 languages), Türkmen Owazy (music), Aşgabat and Turkmenistan Sport. There are no commercial or private TV stations. The nightly official news broadcast, Watan (Homeland), is available on YouTube.[241]

| External video |

|---|

Although officially banned,[95] widespread use of satellite dish receivers allows access to foreign programming, particularly outside Ashgabat.[244] Due to the high mutual intelligibility of the Turkmen and Turkish languages, Turkish-language programs have grown in popularity despite official efforts to discourage viewership.[245][246][247][248]

Internet services are the least developed in Central Asia. Access to Internet services is provided by the government’s ISP company, Turkmentelekom. As of 27 January 2021, Turkmenistan reported an estimated 1,265,794 internet users or roughly 21% of the total population.[249][5][250]

Holidays[edit]

Holidays in Turkmenistan are laid out in the Constitution of Turkmenistan. Holidays in Turkmenistan practiced internationally include New Year’s Day, Nowruz, Eid al-Fitr, and Eid al-Adha. Turkmenistan exclusive holidays include Melon Day, Turkmen Woman’s Day, and the Day of Remembrance for Saparmurat Niyazov.

Education[edit]

Turkmeni students in university uniform

Education is universal and mandatory through the secondary level. Under former President Niyazov, the total duration of primary and secondary education was reduced from 10 to 9 years. President Berdimuhamedov restored 10-year education as of the 2007–2008 school year. Effective 2013, general education in Turkmenistan was expanded to three-stages lasting 12 years: elementary school (grades 1–3), high school – the first cycle of secondary education with duration of 5 years (grades 4–8), and secondary school (grades 9–12).[251][252]

At the end of the 2019–20 academic year, nearly 80,000 Turkmen pupils graduated from high school.[253] As of the 2019–20 academic year, 12,242 of these students were admitted to institutions of higher education in Turkmenistan. An additional 9,063 were admitted to the country’s 42 vocational colleges.[254] An estimated 95,000 Turkmen students were enrolled in institutions of higher education abroad as of Autumn 2019.[255]

Architecture[edit]

The tasks for modern Turkmen architecture are diverse application of modern aesthetics, the search for an architect’s own artistic style, and inclusion of the existing historico-cultural environment. Most major new buildings, especially those in Ashgabat, are faced with white marble. Major projects such as Turkmenistan Tower, Bagt köşgi, Alem Cultural and Entertainment Center, Ashgabat Flagpole have transformed the country’s skyline and promote its identity as a modern, contemporary city.

Sports[edit]

The most popular sport in Turkmenistan is football. The national team has never qualified for the FIFA World Cup but has appeared twice at the AFC Asian Cup, in 2004 and 2019, failing to advance past the group stage at both editions. Another popular sport is archery, Turkmenistan holds league and local competitions for archery. International sports events hosted in Turkmenistan include; the 2021 UCI Track Cycling World Championships, the 2017 Asian Indoor and Martial Arts Games, and the 2018 World Weightlifting Championships.

See also[edit]

- Outline of Turkmenistan

- Index of Turkmenistan-related articles

References[edit]

- ^ ««Turkmenistan is the motherland of Neutrality» is the motto of 2020 | Chronicles of Turkmenistan». En.hronikatm.com. 28 December 2019. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ «Turkmen parliament places Year 2020 under national motto «Turkmenistan – Homeland of Neutrality» – tpetroleum». Turkmenpetroleum.com. 29 December 2019. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ a b «Turkmenistan’s Constitution of 2008» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 May 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ «Turkmenistan». 3 August 2022. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h «Turkmenistan». The World Factbook. United States Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ a b «Dual Citizenship». Ashgabat: U.S. Embassy in Turkmenistan. Archived from the original on 23 May 2020. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

- ^ *Gore, Hayden (2007). «Totalitarianism: The Case of Turkmenistan» (PDF). Human Rights & Human Welfare. Denver: Josef Korbel School of International Studies (Human Rights in Russia and the Former Soviet Republics): 107–116. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- Williamson, Hugh (24 March 2022). «The internet is crucial». Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

Turkmenistan stands out as a totalitarian state. It gives absolutely no scope to dissident opinions and independent media. The regime censors the internet heavily.

- Horák, Slavomír; Šír, Jan (March 2009). Dismantling totalitarianism?: Turkmenistan under Berdimuhamedow (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies. ISBN 9789185937172. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- «Turkmenistan: New president, old ideas». Eurasianet. 15 March 2022. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- «Nations in Transit: Turkemistan». Freedom House. 2016. Archived from the original on 23 May 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- Stronski, Paul (30 January 2017). «Turkmenistan at Twenty-Five: The High Price of Authoritarianism» (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 January 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- Williamson, Hugh (24 March 2022). «The internet is crucial». Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 4 May 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2022.

- ^ a b «Turkmenistan’s president expands his father’s power». Associated Press. Ashgabat. 22 January 2023. Archived from the original on 29 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ Государственный комитет Туркменистана по статистике : Информация о Туркменистане: О Туркменистане Archived 7 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine : Туркменистан — одна из пяти стран Центральной Азии, вторая среди них по площади (491,21 тысяч км2), расположен в юго-западной части региона в зоне пустынь, севернее хребта Копетдаг Туркмено-Хорасанской горной системы, между Каспийским морем на западе и рекой Амударья на востоке.

- ^ «Turkmenistan». The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ^ a b c d «World Economic Outlook Database, October 2022». IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. October 2022. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ «Human Development Report 2021/2022» (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Clark, Larry (1998). Turkmen Reference Grammar. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 50.

- ^ «Turkmenian». Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 13 December 2020.

- ^ «Turkmenistan», The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 19 October 2021, archived from the original on 10 January 2021, retrieved 25 October 2021

- ^ «State Historical and Cultural Park «Ancient Merv»«. UNESCO-WHC. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Tharoor, Kanishk (2016). «LOST CITIES #5: HOW THE MAGNIFICENT CITY OF MERV WAS RAZED – AND NEVER RECOVERED». The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

Once the world’s biggest city, the Silk Road metropolis of Merv in modern Turkmenistan destroyed by Genghis Khan’s son and the Mongols in AD1221 with an estimated 700,000 deaths.

- ^ «BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2019» (PDF). p. 30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- ^ «Turkmen ruler ends free power, gas, water – World News». Hürriyet Daily News. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ AA, DAILY SABAH WITH (17 November 2021). «‘Turkmenistan’s new status in Turkic States significant development’«. Daily Sabah. Archived from the original on 23 February 2022. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ «TURKMENISTAN General information». Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Turkmenistan. Archived from the original on 20 June 2022. Retrieved 22 June 2022.

- ^ a b «Russians ‘flee’ Turkmenistan». BBC News. 20 June 2003. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ a b Spetalnick, Matt (3 November 2015). «Kerry reassures Afghanistan’s neighbors over U.S. troop drawdown». Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 March 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ «As Expected, Son Of Turkmen Leader Easily Wins Election In Familial Transfer Of Power». RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «Turkmenistan: Autocrat president’s son claims landslide win». Deutsche Welle. 15 March 2022. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ «Asia-Pacific – Turkmenistan suspends death penalty». BBC News. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ Zuev, Yury (2002). Early Türks: Essays on history and ideology. Almatý: Daik-Press. p. 157.

- ^ US Library of Congress Country Studies. «Turkmenistan» Archived 22 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ «Ibn Kathir al-Bidaya wa al-Nihaya» Archived 21 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. (in Arabic)

- ^ «Constitutional Law of Turkmenistan on independence and the fundamentals of the state organisation of Turkmenistan» Archived 9 August 2020 at the Wayback Machine; Ведомости Меджлиса Туркменистана», № 15, page 152 – 27 October 1991. Retrieved from the Database of Legislation of Turkmenistan, OSCE Centre in Ashgabat.

- ^ «Independence of Turkmenia Declared After a Referendum» Archived 5 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine; The New York Times – 28 October 1991. Retrieved on 16 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak «Country Profile: Turkmenistan» (PDF). Library of Congress Federal Research Division. February 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 February 2005. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Аннанепесов (Annanepesov), М. (M.) (2000). Gundogdyyev, Ovez (ed.). «Серахское сражение 1855 года (Историко-культурное наследие Туркменистана)» [Serakhs Battle of 1855 (Historical and Cultural Heritage of Turkmenistan)] (in Russian). Istanbul: UNDP. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Казем-Заде (Kazem-Zade), Фируз (Firuz) (2017). Борьба за влияние в Персии. Дипломатическое противостояние России и Англии [Struggle for Influence in Persia. Diplomatic Confrontation between Russia and England] (in Russian). Центрполиграф (Centrpoligraph). ISBN 978-5457028937. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ MacGahan, Januarius (1874). «Campaigning on the Oxus, and the fall of Khiva». New York: Harper & Brothers. Archived from the original on 27 October 2016. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Глуховской (Glukhovskoy), А. (1873). «О положении дел в Аму Дарьинском бассейне» [On the State of Affairs in the Amu Darya Basin] (in Russian). Archived from the original on 27 November 2020. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Paul R. Spickard (2005). Race and Nation: Ethnic Systems in the Modern World. Routledge. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-415-95003-9.

- ^ Scott Cameron Levi (January 2002). The Indian Diaspora in Central Asia and Its Trade: 1550–1900. BRILL. p. 68. ISBN 978-90-04-12320-5.

- ^ Аннанепесов (Annanepesov), М. (M.) (2000). «Ахалтекинские экспедиции (Историко-культурное наследие Туркменистана)» [Akhal-Teke Expeditions (Historical and Cultural Heritage of Turkmenistan)] (in Russian). UNDP. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- ^ Muradov, Ruslan (13 May 2021). «История Ашхабада: время больших перемен» (in Russian). «Туркменистан: золотой век». Archived from the original on 15 May 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ «Comments for the significant earthquake». Significant Earthquake Database. National Geophysical Data Center. Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ Horák, Slavomír; Šír, Jan (March 2009). Dismantling Totalitarianism? Turkmenistan under Berdimuhamedow (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Central Asia-Caucasus Institute & Silk Road Studies Program. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-91 85937-17-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ «Turkmenistan president wins election with 96.9% of vote». The Guardian. London. 13 February 2012. Archived from the original on 19 November 2020. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- ^ Putz, Catherine (14 February 2017). «Turkmenistan, Apparently, Had an Election». The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ «Turkmenistan leader’s son wins presidential election». AP NEWS. Associated Press. 15 March 2022. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ «Serdar Berdimuhamedov sworn in as Turkmenistan’s new president». www.aa.com.tr. Archived from the original on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 4 June 2022.

- ^ Turkmenistan Country Study Guide Volume 1. Washington DC: International Business Publications. 2011. ISBN 9781438749082. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ «Turkmenistan». 8 September 2014. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Stronski, Paul (22 May 2017). Независимому Туркменистану двадцать пять лет: цена авторитаризма. carnegie.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 22 May 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

- ^ «President For Life? Turkmen Leader Signs Mysterious Constitutional Changes Into Law». RFE/RL. 25 September 2020. Archived from the original on 25 September 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ «Turkmen Voters Given Two Hours To Cast Ballots In Senate Election». RFE/RL. 28 March 2021. Archived from the original on 21 May 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ «Туркменистан впервые в истории избрал верхнюю палату парламента» (in Russian). Deutsche Welle. 28 March 2021. Archived from the original on 23 May 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b c «Turkmenistan votes for a new ‘rubber-stamp’ parliament». bne IntelliNews. 26 March 2018. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b c Pannier, Bruce (22 March 2018). «Turkmen Elections Look Like Next Step Toward Dynasty». RFE/RL. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b Clement, Victoria (21 October 2019). «Passing the baton in Turkmenistan». Atlantic Council. Archived from the original on 8 April 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ «TURKMENISTAN PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 25 March 2018 ODIHR Election Assessment Mission Final Report» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ «Turkmenistan’s Constitution of 2008 with Amendments through 2016» (PDF). constituteproject.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ «TURKMENISTAN 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT» (PDF). U.S. Department of State. p. 8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ «Türkmenistanyň Döwlet howpsuzlyk geňeşiniň agzalaryna Türkmenistanyň «Türkmenistanyň Watan goragçysy» diýen hormatly adyny dakmak hakynda» (in Turkmen). «Türkmenistan: Altyn asyr». 4 March 2021. Archived from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ a b «TURKMENISTAN 2020 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT» (PDF). U.S. Department of State. 28 March 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2021. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ «Hukuk Maglumatlary Merkezi» (in Turkmen). Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 11 April 2021.

- ^ «Turkmenistan’s road police detain vehicles of all colours except white». Chronicles of Turkmenistan. 7 January 2018. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Sergeev, Angel (12 January 2018). «Turkmenistan Bans All Non-White Cars From Capital». motor1.com. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- ^ «Turkmenistan holds inauguration of new president (UPDATE)». Trend News Agency. 19 March 2022. Archived from the original on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ «Turkmenistan Politics». The Economist Intelligence Unit. Archived from the original on 29 March 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ «CORRUPTION PERCEPTIONS INDEX». Transparency International. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- ^ «Turkmenistan: A Model Kleptocracy» (PDF). Crude Accountability. June 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 29 July 2021.