Vincent Willem van Gogh (Dutch: [ˈvɪnsɛnt ˈʋɪləm vɑŋ ˈɣɔx] (listen);[note 1] 30 March 1853 – 29 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who posthumously became one of the most famous and influential figures in Western art history. In a decade, he created about 2,100 artworks, including around 860 oil paintings, most of which date from the last two years of his life. They include landscapes, still lifes, portraits and self-portraits, and are characterised by bold colours and dramatic, impulsive and expressive brushwork that contributed to the foundations of modern art. Not commercially successful in his career, he struggled with severe depression and poverty, which eventually led to his suicide at age thirty-seven.

|

Vincent van Gogh |

|

|---|---|

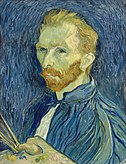

Self-Portrait, 1887, Art Institute of Chicago |

|

| Born |

Vincent Willem van Gogh 30 March 1853 Zundert, Netherlands |

| Died | 29 July 1890 (aged 37)

Auvers-sur-Oise, France |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound |

| Education |

|

| Notable work |

|

| Movement | Post-Impressionism |

| Family | Theodorus van Gogh (brother) |

Born into an upper-middle class family, Van Gogh drew as a child and was serious, quiet, and thoughtful. As a young man, he worked as an art dealer, often traveling, but became depressed after he was transferred to London. He turned to religion and spent time as a Protestant missionary in predominantly Roman Catholic southern Belgium. He drifted in ill health and solitude before taking up painting in 1881, having moved back home with his parents. His younger brother Theo supported him financially; the two kept a long correspondence by letter. His early works, mostly still lifes and depictions of peasant labourers, contain few signs of the vivid colour that distinguished his later work. In 1886, he moved to Paris, where he met members of the avant-garde, including Émile Bernard and Paul Gauguin, who were reacting against the Impressionist sensibility. As his work developed he created a new approach to still lifes and local landscapes. His paintings grew brighter as he developed a style that became fully realised during his stay in Arles in the South of France in 1888. During this period he broadened his subject matter to include series of olive trees, wheat fields and sunflowers.

Van Gogh suffered from psychotic episodes and delusions and though he worried about his mental stability, he often neglected his physical health, did not eat properly and drank heavily. His friendship with Gauguin ended after a confrontation with a razor when, in a rage, he severed part of his own left ear. He spent time in psychiatric hospitals, including a period at Saint-Rémy. After he discharged himself and moved to the Auberge Ravoux in Auvers-sur-Oise near Paris, he came under the care of the homeopathic doctor Paul Gachet. His depression persisted, and on 27 July 1890, Van Gogh is believed to have shot himself in the chest with a revolver, dying from his injuries two days later.

Van Gogh was commercially unsuccessful during his lifetime, and he was considered a madman and a failure. As he became famous only after his suicide, he came to be seen as a misunderstood genius in the public imagination.[6] His reputation grew in the early 20th century as elements of his style came to be incorporated by the Fauves and German Expressionists. He attained widespread critical and commercial success over the ensuing decades, and is remembered as an important but tragic painter whose troubled personality typifies the romantic ideal of the tortured artist. Today, Van Gogh’s works are among the world’s most expensive paintings to have ever sold, and his legacy is honoured by a museum in his name, the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, which holds the world’s largest collection of his paintings and drawings.

Letters

The most comprehensive primary source on Van Gogh is the correspondence between him and his younger brother, Theo. Their lifelong friendship, and most of what is known of Vincent’s thoughts and theories of art, are recorded in the hundreds of letters they exchanged from 1872 until 1890.[7] Theo van Gogh was an art dealer and provided his brother with financial and emotional support as well as access to influential people on the contemporary art scene.[8]

Theo kept all of Vincent’s letters to him;[9] but Vincent kept only a few of the letters he received. After both had died, Theo’s widow Jo Bonger-van Gogh arranged for the publication of some of their letters. A few appeared in 1906 and 1913; the majority were published in 1914.[10][11] Vincent’s letters are eloquent and expressive and have been described as having a «diary-like intimacy»,[8] and read in parts like autobiography.[8] Translator Arnold Pomerans wrote that their publication adds a «fresh dimension to the understanding of Van Gogh’s artistic achievement, an understanding granted to us by virtually no other painter».[12]

Vincent van Gogh in 1873, when he worked at the Goupil & Cie gallery in The Hague;[13] His brother, Theo (pictured right, in 1878), was a life-long supporter and friend.

There are more than 600 letters from Vincent to Theo and around 40 from Theo to Vincent. There are 22 to his sister Wil, 58 to the painter Anthon van Rappard, 22 to Émile Bernard as well as individual letters to Paul Signac, Paul Gauguin, and the critic Albert Aurier. Some are illustrated with sketches.[8] Many are undated, but art historians have been able to place most in chronological order. Problems in transcription and dating remain, mainly with those posted from Arles. While there, Vincent wrote around 200 letters in Dutch, French, and English.[14] There is a gap in the record when he lived in Paris as the brothers lived together and had no need to correspond.[15]

The highly paid contemporary artist Jules Breton was frequently mentioned in Vincent’s letters. In 1875 letters to Theo, Vincent mentions he saw Breton, discusses the Breton paintings he saw at a Salon, and discusses sending one of Breton’s books but only on the condition that it be returned.[16][17] In a March 1884 letter to Rappard he discusses one of Breton’s poems that had inspired one of his own paintings.[18] In 1885 he describes Breton’s famous work The Song of the Lark as being «fine».[19] In March 1880, roughly midway between these letters, Van Gogh set out on an 80-kilometre trip on foot to meet with Breton in the village of Courrières; however, he was apparently intimidated by Breton’s success and/or the high wall around his estate. He turned around and returned without making his presence known.[20][21][22] It appears Breton was unaware of Van Gogh or his attempted visit. There are no known letters between the two artists and Van Gogh is not one of the contemporary artists discussed by Breton in his 1891 autobiography Life of an Artist.

Life

Early years

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born on 30 March 1853 in Groot-Zundert, in the predominantly Catholic province of North Brabant in the Netherlands.[23] He was the oldest surviving child of Theodorus van Gogh (1822–1885), a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church, and his wife, Anna Cornelia Carbentus (1819–1907). Van Gogh was given the name of his grandfather and of a brother stillborn exactly a year before his birth.[note 2] Vincent was a common name in the Van Gogh family. The name had been borne by his grandfather, the prominent art dealer Vincent (1789–1874), and a theology graduate at the University of Leiden in 1811. This Vincent had six sons, three of whom became art dealers, and may have been named after his own great-uncle, a sculptor (1729–1802).[25]

Van Gogh’s mother came from a prosperous family in The Hague,[26] and his father was the youngest son of a minister.[27] The two met when Anna’s younger sister, Cornelia, married Theodorus’s older brother Vincent (Cent). Van Gogh’s parents married in May 1851, and moved to Zundert.[28] His brother Theo was born on 1 May 1857. There was another brother, Cor, and three sisters: Elisabeth, Anna, and Willemina (known as «Wil»). In later life, Van Gogh remained in touch only with Willemina and Theo.[29] Van Gogh’s mother was a rigid and religious woman who emphasized the importance of family to the point of for those around her.[30] Theodorus’s salary as a minister was modest, but the Church also supplied the family with a house, a maid, two cooks, a gardener, a carriage and horse; his mother Anna instilled in the children a duty to uphold the family’s high social position.[31]

Van Gogh was a serious and thoughtful child.[32] He was taught at home by his mother and a governess, and in 1860, was sent to the village school. In 1864, he was placed in a boarding school at Zevenbergen,[33] where he felt abandoned, and he campaigned to come home. Instead, in 1866, his parents sent him to the middle school in Tilburg, where he was also deeply unhappy.[34] His interest in art began at a young age. He was encouraged to draw as a child by his mother,[35] and his early drawings are expressive,[33] but do not approach the intensity of his later work.[36] Constant Cornelis Huijsmans, who had been a successful artist in Paris, taught the students at Tilburg. His philosophy was to reject technique in favour of capturing the impressions of things, particularly nature or common objects. Van Gogh’s profound unhappiness seems to have overshadowed the lessons, which had little effect.[37] In March 1868, he abruptly returned home. He later wrote that his youth was «austere and cold, and sterile».[38]

In July 1869, Van Gogh’s uncle Cent obtained a position for him at the art dealers Goupil & Cie in The Hague.[39] After completing his training in 1873, he was transferred to Goupil’s London branch on Southampton Street, and took lodgings at 87 Hackford Road, Stockwell.[40] This was a happy time for Van Gogh; he was successful at work and, at 20, was earning more than his father. Theo’s wife, Jo Van Gogh-Bonger, later remarked that this was the best year of Vincent’s life. He became infatuated with his landlady’s daughter, Eugénie Loyer, but she rejected him after confessing his feelings; she was secretly engaged to a former lodger. He grew more isolated and religiously fervent. His father and uncle arranged a transfer to Paris in 1875, where he became resentful of issues such as the degree to which the art dealers commodified art, and he was dismissed a year later.[41]

In April 1876, he returned to England to take unpaid work as a supply teacher in a small boarding school in Ramsgate. When the proprietor moved to Isleworth in Middlesex, Van Gogh went with him.[42][43] The arrangement was not successful; he left to become a Methodist minister’s assistant.[44] His parents had meanwhile moved to Etten;[45] in 1876 he returned home at Christmas for six months and took work at a bookshop in Dordrecht. He was unhappy in the position and spent his time doodling or translating passages from the Bible into English, French, and German.[46] He immersed himself in Christianity, and became increasingly pious and monastic.[47] According to his flatmate of the time, Paulus van Görlitz, Van Gogh ate frugally, avoiding meat.[48]

To support his religious conviction and his desire to become a pastor, in 1877, the family sent him to live with his uncle Johannes Stricker, a respected theologian, in Amsterdam.[49] Van Gogh prepared for the University of Amsterdam theology entrance examination;[50] he failed the exam and left his uncle’s house in July 1878. He undertook, but also failed, a three-month course at a Protestant missionary school in Laken, near Brussels.[51]

In January 1879, he took up a post as a missionary at Petit-Wasmes[52] in the working class, coal-mining district of Borinage in Belgium. To show support for his impoverished congregation, he gave up his comfortable lodgings at a bakery to a homeless person and moved to a small hut, where he slept on straw.[53] His humble living conditions did not endear him to church authorities, who dismissed him for «undermining the dignity of the priesthood». He then walked the 75 kilometres (47 mi) to Brussels,[54] returned briefly to Cuesmes in the Borinage, but he gave in to pressure from his parents to return home to Etten. He stayed there until around March 1880,[note 3] which caused concern and frustration for his parents. His father was especially frustrated and advised that his son be committed to the lunatic asylum in Geel.[56][57][note 4]

Van Gogh returned to Cuesmes in August 1880, where he lodged with a miner until October.[59] He became interested in the people and scenes around him, and he recorded them in drawings after Theo’s suggestion that he take up art in earnest. He traveled to Brussels later in the year, to follow Theo’s recommendation that he study with the Dutch artist Willem Roelofs, who persuaded him – in spite of his dislike of formal schools of art – to attend the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts. He registered at the Académie in November 1880, where he studied anatomy and the standard rules of modelling and perspective.[60]

Etten, Drenthe and The Hague

Kee Vos-Stricker with her son Jan c. 1879–80

Van Gogh returned to Etten in April 1881 for an extended stay with his parents.[61] He continued to draw, often using his neighbours as subjects. In August 1881, his recently widowed cousin, Cornelia «Kee» Vos-Stricker, daughter of his mother’s older sister Willemina and Johannes Stricker, arrived for a visit. He was thrilled and took long walks with her. Kee was seven years older than he was and had an eight-year-old son. Van Gogh surprised everyone by declaring his love to her and proposing marriage.[62] She refused with the words «No, nay, never» («nooit, neen, nimmer«).[63] After Kee returned to Amsterdam, Van Gogh went to The Hague to try to sell paintings and to meet with his second cousin, Anton Mauve. Mauve was the successful artist Van Gogh longed to be.[64] Mauve invited him to return in a few months and suggested he spend the intervening time working in charcoal and pastels; Van Gogh returned to Etten and followed this advice.[64]

Late in November 1881, Van Gogh wrote a letter to Johannes Stricker, one which he described to Theo as an attack.[65] Within days he left for Amsterdam.[66] Kee would not meet him, and her parents wrote that his «persistence is disgusting«.[67] In despair, he held his left hand in the flame of a lamp, with the words: «Let me see her for as long as I can keep my hand in the flame.»[67][68] He did not recall the event well, but later assumed that his uncle had blown out the flame. Kee’s father made it clear that her refusal should be heeded and that the two would not marry, largely because of Van Gogh’s inability to support himself.[69]

Mauve took Van Gogh on as a student and introduced him to watercolour, which he worked on for the next month before returning home for Christmas.[70] He quarrelled with his father, refusing to attend church, and left for The Hague.[note 5][71] In January 1882, Mauve introduced him to painting in oil and lent him money to set up a studio.[72][73] Within a month Van Gogh and Mauve fell out, possibly over the viability of drawing from plaster casts.[74] Van Gogh could afford to hire only people from the street as models, a practice of which Mauve seems to have disapproved.[75] In June Van Gogh suffered a bout of gonorrhoea and spent three weeks in hospital.[76] Soon after, he first painted in oils,[77] bought with money borrowed from Theo. He liked the medium, and he spread the paint liberally, scraping from the canvas and working back with the brush. He wrote that he was surprised at how good the results were.[78]

Rooftops, View from the Atelier The Hague, 1882, private collection

By March 1882, Mauve appeared to have gone cold towards Van Gogh, and he stopped replying to his letters.[79] He had learned of Van Gogh’s new domestic arrangement with an alcoholic prostitute, Clasina Maria «Sien» Hoornik (1850–1904), and her young daughter.[80] Van Gogh had met Sien towards the end of January 1882, when she had a five-year-old daughter and was pregnant. She had previously borne two children who died, but Van Gogh was unaware of this.[81] On 2 July, she gave birth to a baby boy, Willem.[82] When Van Gogh’s father discovered the details of their relationship, he put pressure on his son to abandon Sien and her two children. Vincent at first defied him,[83] and considered moving the family out of the city, but in late 1883, he left Sien and the children.[84]

Poverty may have pushed Sien back into prostitution; the home became less happy and Van Gogh may have felt family life was irreconcilable with his artistic development. Sien gave her daughter to her mother and baby Willem to her brother.[85] Willem remembered visiting Rotterdam when he was about 12, when an uncle tried to persuade Sien to marry to legitimise the child.[86] He believed Van Gogh was his father, but the timing of his birth makes this unlikely.[87] Sien drowned herself in the River Scheldt in 1904.[88]

In September 1883, Van Gogh moved to Drenthe in the northern Netherlands. In December driven by loneliness, he went to live with his parents, then in Nuenen, North Brabant.[88]

Emerging artist

Nuenen and Antwerp (1883–1886)

Farm with Stacks of Peat, 1883

In Nuenen, Van Gogh focused on painting and drawing. Working outside and very quickly, he completed sketches and paintings of weavers and their cottages. Van Gogh also completed The Parsonage Garden at Nuenen, which was stolen from the Singer Laren in March 2020.[89][90] From August 1884, Margot Begemann, a neighbour’s daughter ten years his senior, joined him on his forays; she fell in love and he reciprocated, though less enthusiastically. They wanted to marry, but neither side of their families were in favour. Margot was distraught and took an overdose of strychnine, but survived after Van Gogh rushed her to a nearby hospital.[82] On 26 March 1885, his father died of a heart attack.[91]

Van Gogh painted several groups of still lifes in 1885.[92] During his two-year stay in Nuenen, he completed numerous drawings and watercolours and nearly 200 oil paintings. His palette consisted mainly of sombre earth tones, particularly dark brown, and showed no sign of the vivid colours that distinguished his later work.[93]

There was interest from a dealer in Paris early in 1885.[94] Theo asked Vincent if he had paintings ready to exhibit.[95] In May, Van Gogh responded with his first major work, The Potato Eaters, and a series of «peasant character studies» which were the culmination of several years of work.[96] When he complained that Theo was not making enough effort to sell his paintings in Paris, his brother responded that they were too dark and not in keeping with the bright style of Impressionism.[93] In August his work was publicly exhibited for the first time, in the shop windows of the dealer Leurs in The Hague. One of his young peasant sitters became pregnant in September 1885; Van Gogh was accused of forcing himself upon her, and the village priest forbade parishioners to model for him.[97]

-

Worn Out, pencil on watercolour paper, 1882. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam[98]

He moved to Antwerp that November and rented a room above a paint dealer’s shop in the rue des Images (Lange Beeldekensstraat).[99] He lived in poverty and ate poorly, preferring to spend the money Theo sent on painting materials and models. Bread, coffee and tobacco became his staple diet. In February 1886, he wrote to Theo that he could only remember eating six hot meals since the previous May. His teeth became loose and painful.[100] In Antwerp he applied himself to the study of colour theory and spent time in museums—particularly studying the work of Peter Paul Rubens—and broadened his palette to include carmine, cobalt blue and emerald green. Van Gogh bought Japanese ukiyo-e woodcuts in the docklands, later incorporating elements of their style into the background of some of his paintings.[101] He was drinking heavily again,[102] and was hospitalised between February and March 1886,[103] when he was possibly also treated for syphilis.[104][note 6]

After his recovery, despite his antipathy towards academic teaching, he took the higher-level admission exams at the Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp and, in January 1886, matriculated in painting and drawing. He became ill and run down by overwork, poor diet and excessive smoking.[107] He started to attend drawing classes after plaster models at the Antwerp Academy on 18 January 1886. He quickly got into trouble with Charles Verlat, the director of the academy and teacher of a painting class, because of his unconventional painting style. Van Gogh had also clashed with the instructor of the drawing class Franz Vinck. Van Gogh finally started to attend the drawing classes after antique plaster models given by Eugène Siberdt. Soon Siberdt and Van Gogh came into conflict when the latter did not comply with Siberdt’s requirement that drawings express the contour and concentrate on the line. When Van Gogh was required to draw the Venus de Milo during a drawing class, he produced the limbless, naked torso of a Flemish peasant woman. Siberdt regarded this as defiance against his artistic guidance and made corrections to Van Gogh’s drawing with his crayon so vigorously that he tore the paper. Van Gogh then flew into a violent rage and shouted at Siberdt: ‘You clearly do not know what a young woman is like, God damn it! A woman must have hips, buttocks, a pelvis in which she can carry a baby!’ According to some accounts, this was the last time Van Gogh attended classes at the academy and he left later for Paris.[108] On 31 March 1886, which was about a month after the confrontation with Siberdt, the teachers of the academy decided that 17 students, including Van Gogh, had to repeat a year. The story that Van Gogh was expelled from the academy by Siberdt is therefore unfounded.[109]

Paris (1886–1888)

Van Gogh moved to Paris in March 1886 where he shared Theo’s rue Laval apartment in Montmartre and studied at Fernand Cormon’s studio. In June the brothers took a larger flat at 54 rue Lepic.[111] In Paris, Vincent painted portraits of friends and acquaintances, still life paintings, views of Le Moulin de la Galette, scenes in Montmartre, Asnières and along the Seine. In 1885 in Antwerp he had become interested in Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints and had used them to decorate the walls of his studio; while in Paris he collected hundreds of them. He tried his hand at Japonaiserie, tracing a figure from a reproduction on the cover of the magazine Paris Illustre, The Courtesan or Oiran (1887), after Keisai Eisen, which he then graphically enlarged in a painting.[112]

After seeing the portrait of Adolphe Monticelli at the Galerie Delareybarette, Van Gogh adopted a brighter palette and a bolder attack, particularly in paintings such as his Seascape at Saintes-Maries (1888).[113][114] Two years later, Vincent and Theo paid for the publication of a book on Monticelli paintings, and Vincent bought some of Monticelli’s works to add to his collection.[115]

Van Gogh learned about Fernand Cormon’s atelier from Theo.[116] He worked at the studio in April and May 1886,[117] where he frequented the circle of the Australian artist John Russell, who painted his portrait in 1886.[118] Van Gogh also met fellow students Émile Bernard, Louis Anquetin and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – who painted a portrait of him in pastel. They met at Julien «Père» Tanguy’s paint shop,[117] (which was, at that time, the only place where Paul Cézanne’s paintings were displayed). In 1886, two large exhibitions were staged there, showing Pointillism and Neo-impressionism for the first time and bringing attention to Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Theo kept a stock of Impressionist paintings in his gallery on boulevard Montmartre, but Van Gogh was slow to acknowledge the new developments in art.[119]

Conflicts arose between the brothers. At the end of 1886 Theo found living with Vincent to be «almost unbearable».[117] By early 1887, they were again at peace, and Vincent had moved to Asnières, a northwestern suburb of Paris, where he got to know Signac. He adopted elements of Pointillism, a technique in which a multitude of small coloured dots are applied to the canvas so that when seen from a distance they create an optical blend of hues. The style stresses the ability of complementary colours – including blue and orange – to form vibrant contrasts.[95][117]

-

Courtesan (after Eisen), 1887. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

While in Asnières Van Gogh painted parks, restaurants and the Seine, including Bridges across the Seine at Asnières. In November 1887, Theo and Vincent befriended Paul Gauguin who had just arrived in Paris.[120] Towards the end of the year, Vincent arranged an exhibition alongside Bernard, Anquetin, and probably Toulouse-Lautrec, at the Grand-Bouillon Restaurant du Chalet, 43 avenue de Clichy, Montmartre. In a contemporary account, Bernard wrote that the exhibition was ahead of anything else in Paris.[121] There, Bernard and Anquetin sold their first paintings, and Van Gogh exchanged work with Gauguin. Discussions on art, artists, and their social situations started during this exhibition, continued and expanded to include visitors to the show, like Camille Pissarro and his son Lucien, Signac and Seurat. In February 1888, feeling worn out from life in Paris, Van Gogh left, having painted more than 200 paintings during his two years there. Hours before his departure, accompanied by Theo, he paid his first and only visit to Seurat in his studio.[122]

Artistic breakthrough

Arles (1888–89)

Ill from drink and suffering from smoker’s cough, in February 1888 Van Gogh sought refuge in Arles.[14] He seems to have moved with thoughts of founding an art colony. The Danish artist Christian Mourier-Petersen became his companion for two months, and, at first, Arles appeared exotic. In a letter, he described it as a foreign country: «The Zouaves, the brothels, the adorable little Arlésienne going to her First Communion, the priest in his surplice, who looks like a dangerous rhinoceros, the people drinking absinthe, all seem to me creatures from another world.»[123]

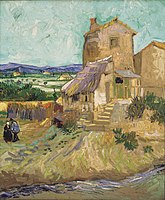

The time in Arles became one of Van Gogh’s more prolific periods: he completed 200 paintings and more than 100 drawings and watercolours.[124] He was enchanted by the local countryside and light; his works from this period are rich in yellow, ultramarine and mauve. They include harvests, wheat fields and general rural landmarks from the area, including The Old Mill (1888), one of seven canvases sent to Pont-Aven on 4 October 1888 in an exchange of works with Paul Gauguin, Émile Bernard, Charles Laval and others.[125]

The portrayals of Arles are informed by his Dutch upbringing; the patchworks of fields and avenues are flat and lacking perspective, but excel in their use of colour.[126]

In March 1888 he painted landscapes using a gridded «perspective frame»; three of the works were shown at the annual exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants. In April, he was visited by the American artist Dodge MacKnight, who was living nearby at Fontvieille.[127][128] On 1 May 1888, for 15 francs per month, he signed a lease for the eastern wing of the Yellow House at 2 place Lamartine. The rooms were unfurnished and had been uninhabited for months.[129]

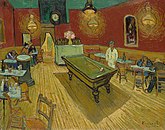

On 7 May, Van Gogh moved from the Hôtel Carrel to the Café de la Gare,[130] having befriended the proprietors, Joseph and Marie Ginoux. The Yellow House had to be furnished before he could fully move in, but he was able to use it as a studio.[131] He wanted a gallery to display his work and started a series of paintings that eventually included Van Gogh’s Chair (1888), Bedroom in Arles (1888), The Night Café (1888), Café Terrace at Night (September 1888), Starry Night Over the Rhone (1888), and Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers (1888), all intended for the decoration for the Yellow House.[132]

Van Gogh wrote that with The Night Café he tried «to express the idea that the café is a place where one can ruin oneself, go mad, or commit a crime».[133] When he visited Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer in June, he gave lessons to a Zouave second lieutenant – Paul-Eugène Milliet[134] – and painted boats on the sea and the village.[135] MacKnight introduced Van Gogh to Eugène Boch, a Belgian painter who sometimes stayed in Fontvieille, and the two exchanged visits in July.[134]

-

The Sower with Setting Sun, 1888. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

-

Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries, June 1888. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Gauguin’s visit (1888)

When Gauguin agreed to visit Arles in 1888, Van Gogh hoped for friendship and to realize his idea of an artists’ collective. Van Gogh prepared for Gauguin’s arrival by painting four versions of Sunflowers in one week.[136] «In the hope of living in a studio of our own with Gauguin,» he wrote in a letter to Theo, «I’d like to do a decoration for the studio. Nothing but large Sunflowers.»[137]

When Boch visited again, Van Gogh painted a portrait of him, as well as the study The Poet Against a Starry Sky.[138][note 7]

In preparation for Gauguin’s visit, Van Gogh bought two beds on advice from the station’s postal supervisor Joseph Roulin, whose portrait he painted. On 17 September, he spent his first night in the still sparsely furnished Yellow House.[140] When Gauguin consented to work and live in Arles with him, Van Gogh started to work on the Décoration for the Yellow House, probably the most ambitious effort he ever undertook.[141] He completed two chair paintings: Van Gogh’s Chair and Gauguin’s Chair.[142]

After much pleading from Van Gogh, Gauguin arrived in Arles on 23 October and, in November, the two painted together. Gauguin depicted Van Gogh in his The Painter of Sunflowers; Van Gogh painted pictures from memory, following Gauguin’s suggestion. Among these «imaginative» paintings is Memory of the Garden at Etten.[143][note 8] Their first joint outdoor venture was at the Alyscamps, when they produced the pendants Les Alyscamps.[144] The single painting Gauguin completed during his visit was his portrait of Van Gogh.[145]

Van Gogh and Gauguin visited Montpellier in December 1888, where they saw works by Courbet and Delacroix in the Musée Fabre.[146] Their relationship began to deteriorate; Van Gogh admired Gauguin and wanted to be treated as his equal, but Gauguin was arrogant and domineering, which frustrated Van Gogh. They often quarrelled; Van Gogh increasingly feared that Gauguin was going to desert him, and the situation, which Van Gogh described as one of «excessive tension», rapidly headed towards crisis point.[147]

-

Paul Gauguin’s Armchair, 1888. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Hospital in Arles (December 1888)

Local newspaper report dated 30 December 1888 recording van Gogh’s self-mutilation.[148]

Portrait of Félix Rey, January 1889, Pushkin Museum; note written by Dr Rey for novelist Irving Stone with sketches of the damage to van Gogh’s ear

The exact sequence that led to the mutilation of van Gogh’s ear is not known. Gauguin said, fifteen years later, that the night followed several instances of physically threatening behaviour.[149] Their relationship was complex and Theo may have owed money to Gauguin, who suspected the brothers were exploiting him financially.[150] It seems likely that Vincent realised that Gauguin was planning to leave.[150] The following days saw heavy rain, leading to the two men being shut in the Yellow House.[151] Gauguin recalled that Van Gogh followed him after he left for a walk and «rushed towards me, an open razor in his hand.»[151] This account is uncorroborated;[152] Gauguin was almost certainly absent from the Yellow House that night, most likely staying in a hotel.[151]

After an altercation on the evening of 23 December 1888,[153] Van Gogh returned to his room where he seemingly heard voices and either wholly or in part severed his left ear with a razor[note 9] causing severe bleeding.[154] He bandaged the wound, wrapped the ear in paper and delivered the package to a woman at a brothel Van Gogh and Gauguin both frequented.[154] Van Gogh was found unconscious the next morning by a policeman and taken to hospital,[157][158] where he was treated by Félix Rey, a young doctor still in training. The ear was brought to the hospital, but Rey did not attempt to reattach it as too much time had passed.[151] Van Gogh researcher and art historian Bernadette Murphy discovered the true identity of the woman named Gabrielle, who died in Arles at the age of 80 in 1952, and whose descendants still live just outside Arles. Gabrielle, known in her youth as «Gaby,» was a 17-year-old cleaning girl at the brothel and other local establishments at the time Van Gogh presented her with his ear.[153][159][160]

Van Gogh had no recollection of the event, suggesting that he may have suffered an acute mental breakdown.[161] The hospital diagnosis was «acute mania with generalised delirium»,[162] and within a few days, the local police ordered that he be placed in hospital care.[163][164] Gauguin immediately notified Theo, who, on 24 December, had proposed marriage to his old friend Andries Bonger’s sister Johanna.[165] That evening, Theo rushed to the station to board a night train to Arles. He arrived on Christmas Day and comforted Vincent, who seemed to be semi-lucid. That evening, he left Arles for the return trip to Paris.[166]

During the first days of his treatment, Van Gogh repeatedly and unsuccessfully asked for Gauguin, who asked a policeman attending the case to «be kind enough, Monsieur, to awaken this man with great care, and if he asks for me tell him I have left for Paris; the sight of me might prove fatal for him.»[167] Gauguin fled Arles, never to see Van Gogh again. They continued to correspond, and in 1890, Gauguin proposed they form a studio in Antwerp. Meanwhile, other visitors to the hospital included Marie Ginoux and Roulin.[168]

Despite a pessimistic diagnosis, Van Gogh recovered and returned to the Yellow House on 7 January 1889.[169] He spent the following month between hospital and home, suffering from hallucinations and delusions of poisoning.[170] In March, the police closed his house after a petition by 30 townspeople (including the Ginoux family) who described him as le fou roux «the redheaded madman»;[163] Van Gogh returned to hospital. Paul Signac visited him twice in March;[171] in April Van Gogh moved into rooms owned by Dr Rey after floods damaged paintings in his own home.[172] Two months later, he left Arles and voluntarily entered an asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. Around this time, he wrote, «Sometimes moods of indescribable anguish, sometimes moments when the veil of time and fatality of circumstances seemed to be torn apart for an instant.»[173]

Van Gogh gave his 1889 Portrait of Doctor Félix Rey to Dr Rey. The physician was not fond of the painting and used it to repair a chicken coop, then gave it away.[174] In 2016, the portrait was housed at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts and estimated to be worth over $50 million.[175]

-

Self-portrait with Bandaged Ear and Pipe, 1889, private collection

-

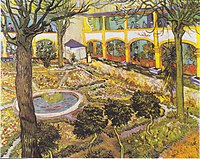

The Courtyard of the Hospital at Arles, 1889, Oskar Reinhart Collection «Am Römerholz», Winterthur, Switzerland

-

Ward in the Hospital in Arles, 1889, Oskar Reinhart Collection «Am Römerholz», Winterthur, Switzerland

Saint-Rémy (May 1889 – May 1890)

Van Gogh entered the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum on 8 May 1889, accompanied by his caregiver, Frédéric Salles, a Protestant clergyman. Saint-Paul was a former monastery in Saint-Rémy, located less than 30 kilometres (19 mi) from Arles, and it was run by a former naval doctor, Théophile Peyron. Van Gogh had two cells with barred windows, one of which he used as a studio.[176] The clinic and its garden became the main subjects of his paintings. He made several studies of the hospital’s interiors, such as Vestibule of the Asylum and Saint-Rémy (September 1889), and its gardens, such as Lilacs (May 1889). Some of his works from this time are characterised by swirls, such as The Starry Night. He was allowed short supervised walks, during which time he painted cypresses and olive trees, including Valley with Ploughman Seen from Above, Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background 1889, Cypresses 1889, Cornfield with Cypresses (1889), Country road in Provence by Night (1890). In September 1889, he produced two further versions of Bedroom in Arles and The Gardener.[177]

Limited access to life outside the clinic resulted in a shortage of subject matter. Van Gogh instead worked on interpretations of other artist’s paintings, such as Millet’s The Sower and Noonday Rest, and variations on his own earlier work. Van Gogh was an admirer of the Realism of Jules Breton, Gustave Courbet and Millet,[178] and he compared his copies to a musician’s interpreting Beethoven.[179]

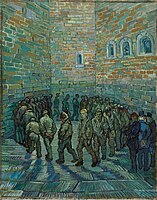

His Prisoners’ Round (after Gustave Doré) (1890) was painted after an engraving by Gustave Doré (1832–1883). Tralbaut suggests that the face of the prisoner in the centre of the painting looking towards the viewer is Van Gogh himself;[180] Jan Hulsker discounts this.[181]

Between February and April 1890, Van Gogh suffered a severe relapse. Depressed and unable to bring himself to write, he was still able to paint and draw a little during this time,[182] and he later wrote to Theo that he had made a few small canvases «from memory … reminisces of the North».[183] Among these was Two Peasant Women Digging in a Snow-Covered Field at Sunset. Hulsker believes that this small group of paintings formed the nucleus of many drawings and study sheets depicting landscapes and figures that Van Gogh worked on during this time. He comments that this short period was the only time that Van Gogh’s illness had a significant effect on his work.[184] Van Gogh asked his mother and his brother to send him drawings and rough work he had done in the early 1880s so he could work on new paintings from his old sketches.[185] Belonging to this period is Sorrowing Old Man («At Eternity’s Gate»), a colour study Hulsker describes as «another unmistakable remembrance of times long past».[98][186] His late paintings show an artist at the height of his abilities, according to the art critic Robert Hughes, «longing for concision and grace».[123]

After the birth of his nephew, Van Gogh wrote, «I started right away to make a picture for him, to hang in their bedroom, branches of white almond blossom against a blue sky.»[187]

1890 Exhibitions and recognition

See also Vincent van Gogh’s display at Les XX, 1890

Albert Aurier praised his work in the Mercure de France in January 1890 and described him as «a genius».[188] In February, Van Gogh painted five versions of L’Arlésienne (Madame Ginoux), based on a charcoal sketch Gauguin had produced when she sat for both artists in November 1888.[189][note 10] Also in February, Van Gogh was invited by Les XX, a society of avant-garde painters in Brussels, to participate in their annual exhibition. At the opening dinner a Les XX member, Henry de Groux, insulted Van Gogh’s work. Toulouse-Lautrec demanded satisfaction, and Signac declared he would continue to fight for Van Gogh’s honour if Lautrec surrendered. De Groux apologised for the slight and left the group.

From 20 March to 27 April 1890, Van Gogh was included in the sixth exhibition of the Société des Artistes Indépendants in the Pavillon de la Ville de Paris on the Champs-Elysées. Van Gogh exhibited ten paintings.[190] While Van Gogh’s exhibit was on display with the Artistes Indépendants in Paris, Claude Monet said that his work was the best in the show.[191]

Auvers-sur-Oise (May–July 1890)

In May 1890, Van Gogh left the clinic in Saint-Rémy to move nearer to both Dr Paul Gachet in the Paris suburb of Auvers-sur-Oise and to Theo. Gachet was an amateur painter and had treated several other artists – Camille Pissarro had recommended him. Van Gogh’s first impression was that Gachet was «iller than I am, it seemed to me, or let’s say just as much.»[192]

The painter Charles Daubigny moved to Auvers in 1861 and in turn drew other artists there, including Camille Corot and Honoré Daumier. In July 1890, Van Gogh completed two paintings of Daubigny’s Garden, one of which is likely his final work.[193]

During his last weeks at Saint-Rémy, his thoughts returned to «memories of the North»,[183] and several of the approximately 70 oils, painted during as many days in Auvers-sur-Oise, are reminiscent of northern scenes.[194] In June 1890, he painted several portraits of his doctor, including Portrait of Dr Gachet, and his only etching. In each the emphasis is on Gachet’s melancholic disposition.[195] There are other paintings which are probably unfinished, including Thatched Cottages by a Hill.[193]

In July, Van Gogh wrote that he had become absorbed «in the immense plain against the hills, boundless as the sea, delicate yellow».[196] He had first become captivated by the fields in May, when the wheat was young and green. In July, he described to Theo «vast fields of wheat under turbulent skies».[197]

He wrote that they represented his «sadness and extreme loneliness» and that the «canvases will tell you what I cannot say in words, that is, how healthy and invigorating I find the countryside».[198] Wheatfield with Crows, although not his last oil work, is from July 1890 and Hulsker discusses it as being associated with «melancholy and extreme loneliness».[199] Hulsker identifies seven oil paintings from Auvers that follow the completion of Wheatfield with Crows.[200]

Research published in 2020 by senior researchers at the museum Louis van Tilborgh and Teio Meedendorp, reviewing findings of Wouter van der Veen, the scientific director of the Institut Van Gogh, concluded that it was «highly plausible» that the exact location where Van Gogh’s final work Tree Roots was some 150 metres (490 ft) from the Auberge Ravoux inn where he was staying, where a stand of trees with a tangle of gnarled roots grew on a hillside. These trees with gnarled roots are shown in a postcard from 1900 to 1910. Van der Veen believes Van Gogh may have been working on the painting just hours before his death.[201][202]

Death

Article on Van Gogh’s death from L’Écho Pontoisien, 7 August 1890

On 27 July 1890, aged 37, Van Gogh is believed to have shot himself in the chest with a 7 mm Lefaucheux pinfire revolver.[203][204] There were no witnesses and he died 30 hours after the incident.[174] The shooting may have taken place in the wheat field in which he had been painting, or in a local barn.[205] The bullet was deflected by a rib and passed through his chest without doing apparent damage to internal organs – probably stopped by his spine. He was able to walk back to the Auberge Ravoux, where he was attended to by two doctors, but without a surgeon present the bullet could not be removed. The doctors tended to him as well as they could, then left him alone in his room, smoking his pipe. The following morning, Theo rushed to his brother’s side, finding him in good spirits. But within hours Vincent’s health began to fail, suffering from an untreated infection resulting from the wound. He died in the early hours of 29 July. According to Theo, Vincent’s last words were: «The sadness will last forever».[206][207][208][209]

Van Gogh was buried on 30 July, in the municipal cemetery of Auvers-sur-Oise. The funeral was attended by Theo van Gogh, Andries Bonger, Charles Laval, Lucien Pissarro, Émile Bernard, Julien Tanguy and Paul Gachet, among twenty family members, friends and locals. Theo had been ill, and his health began to decline further after his brother’s death. Weak and unable to come to terms with Vincent’s absence, he died on 25 January 1891 at Den Dolder and was buried in Utrecht.[210] In 1914, Johanna van Gogh-Bonger had Theo’s body exhumed and moved from Utrecht to be re-buried alongside Vincent’s at Auvers-sur-Oise.[211]

There have been numerous debates as to the nature of Van Gogh’s illness and its effect on his work, and many retrospective diagnoses have been proposed. The consensus is that Van Gogh had an episodic condition with periods of normal functioning.[212] Perry was the first to suggest bipolar disorder in 1947,[213] and this has been supported by the psychiatrists Hemphill and Blumer.[214][215] Biochemist Wilfred Arnold has countered that the symptoms are more consistent with acute intermittent porphyria, noting that the popular link between bipolar disorder and creativity might be spurious.[212] Temporal lobe epilepsy with bouts of depression has also been suggested.[215] Whatever the diagnosis, his condition was likely worsened by malnutrition, overwork, insomnia and alcohol.[215]

The gun Van Gogh was reputed to have used was rediscovered in 1965 and was auctioned, on 19 June 2019, as «the most famous weapon in art history». The gun sold for €162,500 (£144,000; $182,000), almost three times more than expected.[216][217][218]

Style and works

Artistic development

Van Gogh drew, and painted with watercolours while at school, but only a few examples survive and the authorship of some has been challenged.[219] When he took up art as an adult, he began at an elementary level. In early 1882, his uncle, Cornelis Marinus, owner of a well-known gallery of contemporary art in Amsterdam, asked for drawings of The Hague. Van Gogh’s work did not live up to expectations. Marinus offered a second commission, specifying the subject matter in detail, but was again disappointed with the result. Van Gogh persevered; he experimented with lighting in his studio using variable shutters and different drawing materials. For more than a year he worked on single figures – highly elaborate studies in black and white,[note 11] which at the time gained him only criticism. Later, they were recognised as early masterpieces.[221]

In August 1882 Theo gave Vincent money to buy materials for working en plein air. Vincent wrote that he could now «go on painting with new vigour».[222] From early 1883 he worked on multi-figure compositions. He had some of them photographed, but when his brother remarked that they lacked liveliness and freshness, he destroyed them and turned to oil painting. Van Gogh turned to well-known Hague School artists like Weissenbruch and Blommers, and he received technical advice from them as well as from painters like De Bock and Van der Weele, both of the Hague School’s second generation.[223] He moved to Nuenen after a short period of time in Drenthe and began work on several large paintings but destroyed most of them. The Potato Eaters and its companion pieces are the only ones to have survived.[223] Following a visit to the Rijksmuseum Van Gogh wrote of his admiration for the quick, economical brushwork of the Dutch Masters, especially Rembrandt and Frans Hals.[224][note 12] He was aware many of his faults were due to lack of experience and technical expertise,[223] so in November 1885 he travelled to Antwerp and later Paris to learn and develop his skills.[225]

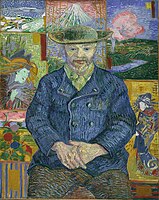

Theo criticised The Potato Eaters for its dark palette, which he thought unsuitable for a modern style.[226] During Van Gogh’s stay in Paris between 1886 and 1887, he tried to master a new, lighter palette. His Portrait of Père Tanguy (1887) shows his success with the brighter palette and is evidence of an evolving personal style.[227] Charles Blanc’s treatise on colour interested him greatly and led him to work with complementary colours. Van Gogh came to believe that the effect of colour went beyond the descriptive; he said that «colour expresses something in itself».[228][229] According to Hughes, Van Gogh perceived colour as having a «psychological and moral weight», as exemplified in the garish reds and greens of The Night Café, a work he wanted to «express the terrible passions of humanity».[230] Yellow meant the most to him, because it symbolised emotional truth. He used yellow as a symbol for sunlight, life, and God.[231]

Van Gogh strove to be a painter of rural life and nature;[232] during his first summer in Arles he used his new palette to paint landscapes and traditional rural life.[233] His belief that a power existed behind the natural led him to try to capture a sense of that power, or the essence of nature in his art, sometimes through the use of symbols.[234] His renditions of the sower, at first copied from Jean-François Millet, reflect the influence of Thomas Carlyle and Friedrich Nietzsche’s thoughts on the heroism of physical labour,[235] as well as Van Gogh’s religious beliefs: the sower as Christ sowing life beneath the hot sun.[236] These were themes and motifs he returned to often to rework and develop.[237] His paintings of flowers are filled with symbolism, but rather than use traditional Christian iconography he made up his own, where life is lived under the sun and work is an allegory of life.[238] In Arles, having gained confidence after painting spring blossoms and learning to capture bright sunlight, he was ready to paint The Sower.[228]

Van Gogh stayed within what he called the «guise of reality»[239] and was critical of overly stylised works.[240] He wrote afterwards that the abstraction of Starry Night had gone too far and that reality had «receded too far in the background».[240] Hughes describes it as a moment of extreme visionary ecstasy: the stars are in a great whirl, reminiscent of Hokusai’s Great Wave, the movement in the heaven above is reflected by the movement of the cypress on the earth below, and the painter’s vision is «translated into a thick, emphatic plasma of paint».[241]

Between 1885 and his death in 1890, Van Gogh appears to have been building an oeuvre,[242] a collection that reflected his personal vision and could be commercially successful. He was influenced by Blanc’s definition of style, that a true painting required optimal use of colour, perspective and brushstrokes. Van Gogh applied the word «purposeful» to paintings he thought he had mastered, as opposed to those he thought of as studies.[243] He painted many series of studies;[239] most of which were still lifes, many executed as colour experiments or as gifts to friends.[244] The work in Arles contributed considerably to his oeuvre: those he thought the most important from that time were The Sower, Night Cafe, Memory of the Garden in Etten and Starry Night. With their broad brushstrokes, inventive perspectives, colours, contours and designs, these paintings represent the style he sought.[240]

Major series

Van Gogh’s stylistic developments are usually linked to the periods he spent living in different places across Europe. He was inclined to immerse himself in local cultures and lighting conditions, although he maintained a highly individual visual outlook throughout. His evolution as an artist was slow, and he was aware of his painterly limitations. He moved home often, perhaps to expose himself to new visual stimuli, and through exposure develop his technical skill.[245] Art historian Melissa McQuillan believes the moves also reflect later stylistic changes, and that Van Gogh used the moves to avoid conflict, and as a coping mechanism for when the idealistic artist was faced with the realities of his then current situation.[246]

Portraits

Van Gogh said portaiture was his greatest interest. «What I’m most passionate about, much much more than all the rest in my profession,» he wrote in 1890, «is the portrait, the modern portrait.»[247] It is «the only thing in painting that moves me deeply and that gives me a sense of the infinite.»[244][248] He wrote to his sister that he wished to paint portraits that would endure, and that he would use colour to capture their emotions and character rather than aiming for photographic realism.[249] Those closest to Van Gogh are mostly absent from his portraits; he rarely painted Theo, Van Rappard or Bernard. The portraits of his mother were from photographs.[250]

Van Gogh painted Arles’ postmaster Joseph Roulin and his family repeatedly. In five versions of La Berceuse (The Lullaby), Van Gogh painted Augustine Roulin quietly holding a rope that rocks the unseen cradle of her infant daughter. Van Gogh had planned for it to be the central image of a triptych, flanked by paintings of sunflowers. [251]

-

La Berceuse (Augustine Roulin), 1889, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Self-portraits

Van Gogh created more than 43 self-portraits between 1885 and 1889.[252][note 13] They were usually completed in series, such as those painted in Paris in mid-1887, and continued until shortly before his death.[253] Generally the portraits were studies, created during periods when he was reluctant to mix with others, or when he lacked models, and so painted himself.[244][254]

The self-portraits reflect a high degree of self-scrutiny.[255] Often they were intended to mark important periods in his life; for example, the mid-1887 Paris series were painted at the point where he became aware of Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne and Signac.[256] In Self-Portrait with Grey Felt Hat, heavy strains of paint spread outwards across the canvas. It is one of his most renowned self-portraits of that period, «with its highly organized rhythmic brushstrokes, and the novel halo derived from the Neo-impressionist repertoire was what Van Gogh himself called a ‘purposeful’ canvas».[257]

They contain a wide array of physiognomical representations.[252] Van Gogh’s mental and physical condition is usually apparent; he may appear unkempt, unshaven or with a neglected beard, with deeply sunken eyes, a weak jaw, or having lost teeth. Some show him with full lips, a long face or prominent skull, or sharpened, alert features. His hair is sometimes depicted in a vibrant reddish hue and at other times ash colored.[252]

Van Gogh’s self-portraits vary stylistically. In those painted after December 1888, the strong contrast of vivid colors highlight the haggard pallor of his skin.[254] Some depict the artist with a beard, others without. He can be seen with bandages in portraits executed just after he mutilated his ear. In only a few does he depict himself as a painter.[252] Those painted in Saint-Rémy show the head from the right, the side opposite his damaged ear, as he painted himself reflected in his mirror.[258][259]

-

Self-Portrait with Grey Felt Hat, Winter 1887–88. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

-

Self-Portrait, 1889. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. His Saint-Rémy self-portraits show his side with the unmutilated ear, as he saw himself in the mirror

-

Self-Portrait Without Beard, c. September 1889. This painting may have been Van Gogh’s last self-portrait. He gave it to his mother as a birthday gift.[260][261]

Flowers

Still Life: Vase with Fourteen Sunflowers, August 1888. National Gallery, London

Van Gogh painted several landscapes with flowers, including roses, lilacs, irises, and sunflowers. Some reflect his interests in the language of colour, and also in Japanese ukiyo-e.[262] There are two series of dying sunflowers. The first was painted in Paris in 1887 and shows flowers lying on the ground. The second set was completed a year later in Arles and is of bouquets in a vase positioned in early morning light.[263] Both are built from thickly layered paintwork, which, according to the London National Gallery, evoke the «texture of the seed-heads».[264]

In these series, Van Gogh was not preoccupied by his usual interest in filling his paintings with subjectivity and emotion; rather, the two series are intended to display his technical skill and working methods to Gauguin,[145] who was about to visit. The 1888 paintings were created during a rare period of optimism for the artist. Vincent wrote to Theo in August 1888: «I’m painting with the gusto of a Marseillais eating bouillabaisse, which won’t surprise you when it’s a question of painting large sunflowers … If I carry out this plan there’ll be a dozen or so panels. The whole thing will therefore be a symphony in blue and yellow. I work on it all these mornings, from sunrise. Because the flowers wilt quickly and it’s a matter of doing the whole thing in one go.»[265]

The sunflowers were painted to decorate the walls in anticipation of Gauguin’s visit, and Van Gogh placed individual works around the Yellow House’s guest room in Arles. Gauguin was deeply impressed and later acquired two of the Paris versions.[145] After Gauguin’s departure, Van Gogh imagined the two major versions of the sunflowers as wings of the Berceuse Triptych, and included them in his Les XX in Brussels exhibit. Today the major pieces of the series are among his best known, celebrated for the sickly connotations of the colour yellow and its tie-in with the Yellow House, the expressionism of the brush strokes, and their contrast against often dark backgrounds.[266]

-

Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, May 1890, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam[267]

-

Still Life: Pink Roses in a Vase, May 1890, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York[267]

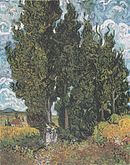

Cypresses and olives

Fifteen canvases depict cypresses, a tree he became fascinated with in Arles.[268] He brought life to the trees, which were traditionally seen as emblematic of death.[234] The series of cypresses he began in Arles featured the trees in the distance, as windbreaks in fields; when he was at Saint-Rémy he brought them to the foreground.[269] Vincent wrote to Theo in May 1889: «Cypresses still preoccupy me, I should like to do something with them like my canvases of sunflowers»; he went on to say, «They are beautiful in line and proportion like an Egyptian obelisk.»[270]

In mid-1889, and at his sister Wil’s request, Van Gogh painted several smaller versions of Wheat Field with Cypresses.[271] The works are characterised by swirls and densely painted impasto, and include The Starry Night, in which cypresses dominate the foreground.[268] In addition to this, other notable works on cypresses include Cypresses (1889), Cypresses with Two Figures (1889–90), and Road with Cypress and Star (1890).[272]

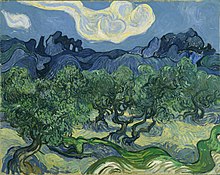

During the last six or seven months of the year 1889, he had also created at least fifteen paintings of olive trees, a subject which he considered as demanding and compelling.[273] Among these works are Olive Trees with the Alpilles in the Background (1889), about which in a letter to his brother Van Gogh wrote, «At last I have a landscape with olives».[272] While in Saint-Rémy, Van Gogh spent time outside the asylum, where he painted trees in the olive groves. In these works, natural life is rendered as gnarled and arthritic as if a personification of the natural world, which are, according to Hughes, filled with «a continuous field of energy of which nature is a manifestation».[234]

-

Cypresses in Starry Night, a reed pen drawing executed by Van Gogh after the painting in 1889.

-

Cypresses and Two Women, February 1890. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

-

Cypresses, 1889. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Orchards

The Flowering Orchards (also the Orchards in Blossom) are among the first groups of work completed after Van Gogh’s arrival in Arles in February 1888. The 14 paintings are optimistic, joyous and visually expressive of the burgeoning spring. They are delicately sensitive and unpopulated. He painted swiftly, and although he brought to this series a version of Impressionism, a strong sense of personal style began to emerge during this period. The transience of the blossoming trees, and the passing of the season, seemed to align with his sense of impermanence and belief in a new beginning in Arles. During the blossoming of the trees that spring, he found «a world of motifs that could not have been more Japanese».[274] Vincent wrote to Theo on 21 April 1888 that he had 10 orchards and «one big [painting] of a cherry tree, which I’ve spoiled».[275]

During this period Van Gogh mastered the use of light by subjugating shadows and painting the trees as if they are the source of light – almost in a sacred manner.[274] Early the following year he painted another smaller group of orchards, including View of Arles, Flowering Orchards.[276] Van Gogh was enthralled by the landscape and vegetation of the south of France, and often visited the farm gardens near Arles. In the vivid light of the Mediterranean climate his palette significantly brightened.[277]

-

Pink Peach Tree in Blossom (Reminiscence of Mauve), watercolour, March 1888. Kröller-Müller Museum

-

The Pink Orchard also Orchard with Blossoming Apricot Trees, March 1888. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

-

Orchard in Blossom, Bordered by Cypresses, April 1888. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Wheat fields

Van Gogh made several painting excursions during visits to the landscape around Arles. He made paintings of harvests, wheat fields and other rural landmarks of the area, including The Old Mill (1888); a good example of a picturesque structure bordering the wheat fields beyond.[125] At various points, Van Gogh painted the view from his window – at The Hague, Antwerp, and Paris. These works culminated in The Wheat Field series, which depicted the view from his cells in the asylum at Saint-Rémy.[278]

Many of the late paintings are sombre but essentially optimistic and, right up to the time of Van Gogh’s death, reflect his desire to return to lucid mental health. Yet some of his final works reflect his deepening concerns.[279][280] Writing in July 1890, from Auvers, Van Gogh said that he had become absorbed «in the immense plain against the hills, boundless as the sea, delicate yellow».[196]

Van Gogh was captivated by the fields in May when the wheat was young and green. His Wheatfields at Auvers with White House shows a more subdued palette of yellows and blues, which creates a sense of idyllic harmony.[281]

About 10 July 1890, Van Gogh wrote to Theo of «vast fields of wheat under troubled skies».[282] Wheatfield with Crows shows the artist’s state of mind in his final days; Hulsker describes the work as a «doom-filled painting with threatening skies and ill-omened crows».[199] Its dark palette and heavy brushstrokes convey a sense of menace.[283]

-

Enclosed Wheat Field with Rising Sun, May 1889, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

-

Wheat Fields, early June 1889. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo

Reputation and legacy

After Van Gogh’s first exhibitions in the late 1880s, his reputation grew steadily among artists, art critics, dealers and collectors.[284] In 1887, André Antoine hung Van Gogh’s alongside works of Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, at the Théâtre Libre in Paris; some were acquired by Julien Tanguy.[285] In 1889, his work was described in the journal Le Moderniste Illustré by Albert Aurier as characterised by «fire, intensity, sunshine».[286] Ten paintings were shown at the Société des Artistes Indépendants, in Brussels in January 1890.[287] French president Marie François Sadi Carnot was said to have been impressed by Van Gogh’s work.[288]

After Van Gogh’s death, memorial exhibitions were held in Brussels, Paris, The Hague and Antwerp. His work was shown in several high-profile exhibitions, including six works at Les XX; in 1891 there was a retrospective exhibition in Brussels.[287] In 1892, Octave Mirbeau wrote that Van Gogh’s suicide was an «infinitely sadder loss for art … even though the populace has not crowded to a magnificent funeral, and poor Vincent van Gogh, whose demise means the extinction of a beautiful flame of genius, has gone to his death as obscure and neglected as he lived.»[285]

Theo died in January 1891, removing Vincent’s most vocal and well-connected champion.[289] Theo’s widow Johanna van Gogh-Bonger was a Dutchwoman in her twenties who had not known either her husband or her brother-in-law very long and who suddenly had to take care of several hundreds of paintings, letters and drawings, as well as her infant son, Vincent Willem van Gogh.[284][note 14] Gauguin was not inclined to offer assistance in promoting Van Gogh’s reputation, and Johanna’s brother Andries Bonger also seemed lukewarm about his work.[284] Aurier, one of Van Gogh’s earliest supporters among the critics, died of typhoid fever in 1892 at the age of 27.[291]

Painter on the Road to Tarascon, August 1888 (destroyed by fire in the Second World War)

In 1892, Émile Bernard organised a small solo show of Van Gogh’s paintings in Paris, and Julien Tanguy exhibited his Van Gogh paintings with several consigned from Johanna van Gogh-Bonger. In April 1894, the Durand-Ruel Gallery in Paris agreed to take 10 paintings on consignment from Van Gogh’s estate.[291] In 1896, the Fauvist painter Henri Matisse, then an unknown art student, visited John Russell on Belle Île off Brittany.[292][293] Russell had been a close friend of Van Gogh; he introduced Matisse to the Dutchman’s work, and gave him a Van Gogh drawing. Influenced by Van Gogh, Matisse abandoned his earth-coloured palette for bright colours.[293][294]

In Paris in 1901, a large Van Gogh retrospective was held at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery, which excited André Derain and Maurice de Vlaminck, and contributed to the emergence of Fauvism.[291] Important group exhibitions took place with the Sonderbund artists in Cologne in 1912, the Armory Show, New York in 1913, and Berlin in 1914.[295] Henk Bremmer was instrumental in teaching and talking about Van Gogh,[296] and introduced Helene Kröller-Müller to Van Gogh’s art; she became an avid collector of his work.[297] The early figures in German Expressionism such as Emil Nolde acknowledged a debt to Van Gogh’s work.[298] Bremmer assisted Jacob Baart de la Faille, whose catalogue raisonné L’Oeuvre de Vincent van Gogh appeared in 1928.[299][note 15]

Van Gogh’s fame reached its first peak in Austria and Germany before World War I,[302] helped by the publication of his letters in three volumes in 1914.[303] His letters are expressive and literate, and have been described as among the foremost 19th-century writings of their kind.[8] These began a compelling mythology of Van Gogh as an intense and dedicated painter who suffered for his art and died young.[304] In 1934, the novelist Irving Stone wrote a biographical novel of Van Gogh’s life titled Lust for Life, based on Van Gogh’s letters to Theo.[305] This novel and the 1956 film further enhanced his fame, especially in the United States where Stone surmised only a few hundred people had heard of Van Gogh prior to his surprise best-selling book.[306][307]

In 1957, Francis Bacon based a series of paintings on reproductions of Van Gogh’s The Painter on the Road to Tarascon, the original of which was destroyed during the Second World War. Bacon was inspired by an image he described as «haunting», and regarded Van Gogh as an alienated outsider, a position which resonated with him. Bacon identified with Van Gogh’s theories of art and quoted lines written to Theo: «[R]eal painters do not paint things as they are … [T]hey paint them as they themselves feel them to be.»[308]

Van Gogh’s works are among the world’s most expensive paintings. Those sold for over US$100 million (today’s equivalent) include Portrait of Dr Gachet,[309] Portrait of Joseph Roulin and Irises. The Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired a copy of Wheat Field with Cypresses in 1993 for US$57 million by using funds donated by publisher, diplomat and philanthropist Walter Annenberg.[310] In 2015, L’Allée des Alyscamps sold for US$66.3 million at Sotheby’s, New York, exceeding its reserve of US$40 million.[311]

Minor planet 4457 van Gogh is named in his honour.[312]

In October 2022, two activists protesting the effects of the fossil fuel industry on climate change threw a can of tomato soup on Van Gogh’s Sunflowers in the National Gallery, London, and then glued their hands to the gallery wall. As the painting was covered by glass it was not damaged. [313][314]

Van Gogh Museum

The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

Van Gogh’s nephew and namesake, Vincent Willem van Gogh (1890–1978),[315] inherited the estate after his mother’s death in 1925. During the early 1950s he arranged for the publication of a complete edition of the letters presented in four volumes and several languages. He then began negotiations with the Dutch government to subsidise a foundation to purchase and house the entire collection.[316] Theo’s son participated in planning the project in the hope that the works would be exhibited under the best possible conditions. The project began in 1963; architect Gerrit Rietveld was commissioned to design it, and after his death in 1964 Kisho Kurokawa took charge.[317] Work progressed throughout the 1960s, with 1972 as the target for its grand opening.[315]

The Van Gogh Museum opened in the Museumplein in Amsterdam in 1973.[318] It became the second most popular museum in the Netherlands, after the Rijksmuseum, regularly receiving more than 1.5 million visitors a year. In 2015 it had a record 1.9 million.[319] Eighty-five percent of the visitors come from other countries.[320]

Nazi-looted art

During the Nazi period (1933–1945) a great number of artworks by Van Gogh changed hands, many of them looted from Jewish collectors who were forced into exile or murdered. Some of these works have disappeared into private collections. Others have since resurfaced in museums, or at auction, or have been reclaimed, often in high-profile lawsuits, by their former owners.[321] The German Lost Art Foundation still lists dozens of missing van Goghs[322] and the American Alliance of Museums lists 73 van Goghs on the Nazi Era Provenance Internet Portal.[323]

References

Explanatory footnotes

- ^ The pronunciation of Van Gogh varies in both English and Dutch. Especially in British English it is [2] or sometimes .[3] American dictionaries list , with a silent gh, as the most common pronunciation.[4] In the dialect of Holland, it is [ˈvɪnsɛnt fɑŋˈ xɔx] ( listen), with a voiceless v and g. He grew up in Brabant and used Brabant dialect in his writing; his own pronunciation was thus likely [vɑɲ ˈʝɔç], with a voiced v and palatalised g and gh. In France, where much of his work was produced, it is [vɑ̃ ɡɔɡ(ə)].[5]

- ^ It has been suggested that being given the same name as his dead elder brother might have had a deep psychological impact on the young artist, and that elements of his art, such as the portrayal of pairs of male figures, can be traced back to this.[24]

- ^ Hulsker suggests that Van Gogh returned to the Borinage and then back to Etten in this period.[55]

- ^ See Jan Hulsker’s speech The Borinage Episode and the Misrepresentation of Vincent van Gogh, Van Gogh Symposium, 10–11 May 1990.[58]

- ^ «At Christmas I had a rather violent argument with Pa, and feelings ran so high that Pa said it would be better if I left home. Well, it was said so decidedly that I actually left the same day.»

- ^ The only evidence for this is from interviews with the grandson of the doctor.[105] For an overall review see Naifeh and Smith.[106]

- ^ Boch’s sister Anna (1848–1936), also an artist, purchased The Red Vineyard in 1890.[139]

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 719 Vincent to Theo van Gogh. Arles, Sunday, 11 or Monday, 12 November 1888:I’ve been working on two canvases … A reminiscence of our garden at Etten with cabbages, cypresses, dahlias and figures … Gauguin gives me courage to imagine, and the things of the imagination do indeed take on a more mysterious character.

- ^ Theo and his wife, Gachet and his son, and Signac, who saw Van Gogh after the bandages were removed, maintained that only the earlobe had been removed.[154] According to Doiteau and Leroy, the diagonal cut removed the lobe and probably a little more.[155] The policeman and Rey both claimed Van Gogh severed the entire outer ear;[154] Rey repeated his account in 1930, writing a note for novelist Irving Stone and including a sketch of the line of the incision.[156]

- ^ The version intended for Ginoux is lost. It was an attempt to deliver this painting to her in Arles that precipitated his February relapse.[182]

- ^ Artists working in black and white, e.g. for illustrated papers like The Graphic or The Illustrated London News were among Van Gogh’s favourites.[220]

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 535 To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, on or about Tuesday, 13 October 1885:What particularly struck me when I saw the old Dutch paintings again is that they were usually painted quickly. That these great masters like Hals, Rembrandt, Ruisdael – so many others – as far as possible just put it straight down – and didn’t come back to it so very much. And – this, too, please – that if it worked, they left it alone. Above all I admired hands by Rembrandt and Hals – hands that lived, but were not finished in the sense that people want to enforce nowadays … In the winter I’m going to explore various things regarding manner that I noticed in the old paintings. I saw a great deal that I needed. But this above all things – what they call – dashing off – you see that’s what the old Dutch painters did famously. That – dashing off – with a few brushstrokes, they won’t hear of it now – but how true the results are.

- ^ Rembrandt is one of the few major painters to exceed this volume of self-portraits, producing over 50, but he did so over a forty-year period.[252]

- ^ Her husband had been the sole support of the family, and Johanna was left with only an apartment in Paris, a few items of furniture, and her brother-in-law’s paintings, which at the time were «looked upon as having no value at all».[290]

- ^ In de la Faille’s 1928 catalogue each of Van Gogh’s works was assigned a number. These numbers preceded by the letter «F» are frequently used when referring to a particular painting or drawing.[300] Not all the works listed in the original catalogue are now believed to be authentic works of Van Gogh.[301]

Citations

- ^ «Sunflowers – Van Gogh Museum». vangoghmuseum.nl. Archived from the original on 29 October 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ^ «BBC – Magazine Monitor: How to Say: Van Gogh». BBC. 22 January 2010. Archived from the original on 26 September 2016. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ^ Sweetman (1990), 7.

- ^ Davies (2007), p. 83.

- ^ Veltkamp, Paul. «Pronunciation of the Name ‘Van Gogh’«. vggallery.com. Archived from the original on 22 September 2015.

- ^ McQuillan (1989), 9.

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), «Van Gogh: The Letters».

- ^ a b c d e McQuillan (1989), 19.

- ^ Pomerans (1997), xv.

- ^ Rewald (1986), 248.

- ^ Pomerans (1997), ix, xv.

- ^ Pomerans (1997), ix.

- ^ Pickvance (1986), 129; Tralbaut (1981), 39.

- ^ a b Hughes (1990), 143.

- ^ Pomerans (1997), i–xxvi.

- ^ «Vincent van Gogh to Theo van Gogh : 9 December 1875». www.webexhibits.org. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ «034 (034, 27): To Theo van Gogh. Paris, Monday, 31 May 1875. – Vincent van Gogh Letters». www.vangoghletters.org. Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ «The Poem That Inspired a Van Gogh Painting, Written in His Hand». The Raab Collection. Archived from the original on 17 April 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ «500 (503, 406): To Theo van Gogh. Nuenen, Monday, 4 and Tuesday, 5 May 1885. – Vincent van Gogh Letters». www.vangoghletters.org. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Route, Van Gogh. «Vincent van Gogh in Borinage, Belgium». Van Gogh Route. Archived from the original on 27 March 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ hoakley (6 April 2017). «Jules Breton’s Eternal Harvest: 4 1877–1889». The Eclectic Light Company. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ «AN ARTIST IS BORN». AwesomeStories.com. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ Pomerans (1997), 1.

- ^ Lubin (1972), 82–84.

- ^ Erickson (1998), 9.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 14–16.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 59.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 18.

- ^ Walther & Metzger (1994), 16.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 23–25.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 31–32.

- ^ Sweetman (1990), 13.

- ^ a b Tralbaut (1981), 25–35.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 45–49.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 36–50.

- ^ Hulsker (1980), 8–9.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 48.

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 403. Vincent to Theo van Gogh, Nieuw-Amsterdam, on or about Monday, 5 November 1883.

- ^ Walther & Metzger (1994), 20.

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 007. Vincent to Theo van Gogh, The Hague, Monday, 5 May 1873.

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 35–47.

- ^ Pomerans (1997), xxvii.

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 088. Vincent to Theo van Gogh. Isleworth, Friday, 18 August 1876.

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 47–56.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 113.

- ^ Callow (1990), 54.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 146–147.

- ^ Sweetman (1990), 175.

- ^ McQuillan (1989), 26; Erickson (1998), 23.

- ^ Grant (2014), p. 9.

- ^ Hulsker (1990), 60–62, 73.

- ^ Sweetman (1990), 101.

- ^ Fell (2015), 17.

- ^ Callow (1990), 72.

- ^ Geskó (2006), 48.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 209–210, 488–489.

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 186. Vincent to Theo van Gogh. Etten, Friday, 18 November 1881.

- ^ Erickson (1998), 67–68.

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 156. Vincent to Theo van Gogh. Cuesmes, Friday, 20 August 1880.

- ^ Tralbaut (1981), 67–71.

- ^ Pomerans (1997), 83.

- ^ Sweetman (1990), 145.

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 179. Vincent to Theo van Gogh. Etten, Thursday, 3 November 1881.

- ^ a b Naifeh & Smith (2011), 239–240.

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 189. Vincent to Theo van Gogh. Etten, Wednesday, 23 November 1881.

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 193. Vincent to Theo van Gogh, Etten, on or about Friday, 23 December 1881, describing the visit in more detail.

- ^ a b Van Gogh (2009), Letter 228. Vincent to Theo van Gogh, The Hague, on or about Tuesday, 16 May 1882.

- ^ Sweetman (1990), 147.

- ^ Gayford (2006), 125.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 250–252.

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 194. Vincent to Theo van Gogh, The Hague, Thursday 29 December 1881

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 196. Vincent to Theo van Gogh. The Hague, on or about Tuesday, 3 January 1882.

- ^ Walther & Metzger (1994), 64.

- ^ Van Gogh (2009), Letter 219.

- ^ Naifeh & Smith (2011), 258.