Как правильно пишется словосочетание «великая держава»

- Как правильно пишется слово «великий»

- Как правильно пишется слово «держать»

Делаем Карту слов лучше вместе

Привет! Меня зовут Лампобот, я компьютерная программа, которая помогает делать

Карту слов. Я отлично

умею считать, но пока плохо понимаю, как устроен ваш мир. Помоги мне разобраться!

Спасибо! Я стал чуточку лучше понимать мир эмоций.

Вопрос: совдепия — это что-то нейтральное, положительное или отрицательное?

Ассоциации к словосочетанию «великая держава»

Синонимы к словосочетанию «великая держава»

Предложения со словосочетанием «великая держава»

- Причины трений между двумя великими державами станут более ясными по мере развития повествования о подводной войне.

- Отождествление государственного величия и имперскости делает адаптацию к утрате статуса великой державы непростой задачей для национального сознания бывшей метрополии.

- Россия снова становилась великой державой, и значит, над ней начинали сгущаться тучи.

- (все предложения)

Цитаты из русской классики со словосочетанием «великая держава»

- Конечно, Франция — не Бельгия, не Сербия, Франция — великая держава, и она нам оказывает великую помощь, как наша союзница.

- Студзинский. Была у нас Россия — великая держава!..

- однако ж история, которая лжет только из году в год (первое апреля и еще 29 февраля), уверяет, что они, проснувшись на другой день, снова читали трактат свой, снова утвердили его и (что не всегда делают и великие державы европейские) старались исполнять во всей точности.

- (все

цитаты из русской классики)

Значение словосочетания «великая держава»

-

Вели́кая держа́ва — условное, неюридическое обозначение государств (держав), которые, благодаря своему политическому влиянию, играют определяющую роль «в системе международных и международно-правовых отношений». (Википедия)

Все значения словосочетания ВЕЛИКАЯ ДЕРЖАВА

Афоризмы русских писателей со словом «великий»

- …всякая наука, — изучение тех ходов, которыми шли все великие умы человечества для уяснения истины. С тех пор, как есть история, есть выдающиеся умы, которые сделали человечество тем, что оно есть…

- Неуместно и несвоевременно только самое великое.

- Великие платят за искусство жизнью, маленькие — зарабатывают им на жизнь.

- (все афоризмы русских писателей)

Отправить комментарий

Дополнительно

Сомневаетесь в ответе?

Найдите правильный ответ на вопрос ✅ «Держава с маленькой или большой буквы пишется? …» по предмету 📘 Русский язык, а если вы сомневаетесь в правильности ответов или ответ отсутствует, то попробуйте воспользоваться умным поиском на сайте и найти ответы на похожие вопросы.

Смотреть другие ответы

Да, это нарицательное слово

Опубликовано 27.09.2017 по предмету Русский язык от Гость

>>

Ответ оставил Гость

Да, это нарицательное слово

Оцени ответ

Не нашёл ответ?

Если тебя не устраивает ответ или его нет, то попробуй воспользоваться поиском на сайте и найти похожие ответы по предмету Русский язык.

Найти другие ответы

Самые новые вопросы

Литература, опубликовано 17.03.2020

сочинение на тему не менее 150 слов

Как вы думаете, почему а. с. пушкин, выслушав первые главы «мертвых душ» (эти главы читал ему сам гоголь), воскликнул: «боже, как грустна наша…

Українська література, опубликовано 05.03.2020

яким твором перегукується драматичний етюд О. Олеся «По дорозі в Казку»?

Алгебра, опубликовано 24.05.2019

Среди решений уравнения x+5y−24=0 определи такую пару, которая состоит из двух таких чисел, первое из которых в 3 раза больше второго.

Физика, опубликовано 19.03.2019

коли до малого поршня гідравлічної машини прикладають силу 6н, великий поршень може підняти вантаж масою до 15 кг. площя малого поршня дорівнює 5 см2 . яка площя великого поршня?

Физика, опубликовано 19.03.2019

коли до малого поршня гідравлічної машини прикладають силу 6н, великий поршень може підняти вантаж масою до 15 кг. площя малого поршня дорівнює 5 см2 . яка площя великого поршня?

Голосование за лучший ответ

Tenzen

Мастер

(1646)

5 лет назад

смотря какая

Ди Н

Просветленный

(37245)

5 лет назад

смотря какая держава. наша — с большой

Игорь Макаров.

Мастер

(1024)

5 лет назад

С маленькой.

Han Asparuh

Мыслитель

(8337)

5 лет назад

Держава, страна, государство, пишется с маленькой буквы…

Умная

Мастер

(1002)

5 лет назад

Если в не путать орфографию с политикой, то с маленькой…

Филин

Мудрец

(16974)

5 лет назад

Смешной вопрос. Обычно с маленькой буквы пишут. Но есть особые случаи, когда с большой. Например, М. А. Булгаков в романе «Белая гвардия» называет город Городом, потому что в это название он вложил особый смысл. Сейчас этого Города уже не существует, к сожалению…

Автор Надя Лещенко задал вопрос в разделе Лингвистика

С какой буквы пишется держава? С маленькой или с большой и получил лучший ответ

Ответ от Tenzen[гуру]

смотря какая

Ответ от фил_ин_©_®[гуру]

Смешной вопрос. Обычно с маленькой буквы пишут. Но есть особые случаи, когда с большой. Например, М. А. Булгаков в романе «Белая гвардия» называет город Городом, потому что в это название он вложил особый смысл. Сейчас этого Города уже не существует, к сожалению…

Ответ от Han Asparuh[гуру]

Держава, страна, государство, пишется с маленькой буквы…

Ответ от Ѓмная[гуру]

Если в не путать орфографию с политикой, то с маленькой…

Ответ от Игорь Макаров.[мастер]

С маленькой.

Ответ от Ди Н[гуру]

смотря какая держава. наша — с большой

Ответ от 3 ответа[гуру]

Привет! Вот подборка тем с похожими вопросами и ответами на Ваш вопрос: С какой буквы пишется держава? С маленькой или с большой

Обсуждение Украинская держава на Википедии

Посмотрите статью на википедии про Обсуждение Украинская держава

Вели́кая держа́ва — условное, неюридическое обозначение государств (держав), которые, благодаря своему политическому влиянию, играют определяющую роль «в системе международных и международно-правовых отношений»[1]. Понятие «великая держава» получило широкое распространение после завершения наполеоновских войн и создания системы «Европейского концерта»[2][3]. В научный оборот фраза была введена немецким историком Леопольдом фон Ранке, в 1833 году опубликовавшим фундаментальную работу под названием «Великие державы»[4] (нем. «Die großen Mächte»[5]).

Содержание

- 1 История

- 2 Характеристики «великой державы»

- 2.1 Ресурсный потенциал

- 2.2 География интересов

- 3 Примечания

- 4 Литература

История

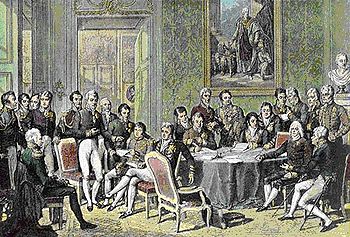

Венский конгресс великих держав в начале XIX века

Зал заседаний Совета Безопасности ООН

Статус «великих держав» впервые получил формальное признание на Венском конгрессе 1814—1815 гг.[6][3] С созданием Четверного союза, данный статус укрепился за четырьмя странами — участницами антифранцузской коалиции (Англия, Россия, Австрия, Пруссия) и — с 1818 года — за Францией[7]. Отличительной чертой новой системы международных отношений (так называемой «концертной дипломатии») стала необходимость согласия великих держав на любые территориальные изменения в послевоенной Европе[8].

Многие источники сходятся во мнении, что к началу XX века в Европе существовало пять—шесть держав[9], претендовавших на статус «великих»: Великобритания, Россия, Франция, Германская империя (как преемница Пруссии), Италия (после объединения страны в 1860-х) и Австро-Венгрия (как преемница Австрийской империи). Последняя навсегда утратила статус «великой державы» после поражения в Первой мировой войне и последовавшего распада Дунайской монархии[10].

Согласно подсчетам ряда историков, великие державы так или иначе участвовали в большинстве международных конфликтов и войн XIX-XX веков[11].

По завершении Второй мировой войны, статус «великих держав» неофициально сохраняют пятеро постоянных членов Совета Безопасности ООН. Примечательно, что все эти страны являются ядерными державами[12].

Долгое время великие державы использовали своё влияние на международных переговорах для заключения «неравноправных» соглашений, без учета интереса других участников. Ситуация стала меняться после Второй мировой войны. Хотя сегодня великие державы не в силах самостоятельно изменять «общие договоры», они, как правило, способны заблокировать «нежелательный им пересмотр».[13].

Характеристики «великой державы»

Обычно исследователи выделяют три «измерения», по которым проводится оценка соответствия державы статусу «великой»:

- мощь державы (её ресурсный потенциал)

- «пространственное измерение», или «география интересов» (критерий, позволяющий отличить великую державу от региональной)

- статус (формальное или неформальное признание за государством статуса «великой державы»).[14]

Ресурсный потенциал

Различные исследователи по-разному трактуют определение «великой державы». Так, британский историк А. Тэйлор[ru] считал, что каждая держава, претендующая на статус великой, должна пройти «испытание войной». Подобного мнения придерживался и Куинси Райт, и ряд других специалистов по международному праву и истории дипломатии. Согласно их точке зрения, приобрести статус великой державы можно было, «в первую очередь, за счёт военного престижа, военного потенциала и военных успехов». Позднейшие исследователи придавали термину более широкое значение, связывая его с «людскими, военными, экономическими и политическими ресурсами».[15]

По меткому выражению французского историка Ж.-Б. Дюроселя[ru], великой державой должна считаться «та, которая способна отстоять свою независимость в противоборстве с любой другой державой». Согласно иной точке зрения, «великая держава должна быть не менее могущественна, чем коалиция обычных государств». Один из общепринятых постулатов гласит, что «великая держава должна уметь вести великую войну». Последнее парадоксальным образом сочетается с устоявшимся взглядом на «великие войны» как на войны, «в которых участвуют великие державы».[16]

По мнению И. И. Лукашука, критерии великих держав менялись со временем. Если изначально основное внимание уделялось военной силе, позднее всё бо́льшую роль стали играть экономический и научно-технический потенциал государства, его «морально-политический авторитет».[17]

География интересов

Анализируя черты, присущие «великой державе», многие авторы указывают на «географическую плоскость её влияния». Различные источники отмечают «надрегиональный» характер интересов подобного государства, как и способность последнего отстаивать свои интересы на международной арене.[18] Кроме того, «пространственное измерение» может служить удобным маркером для выделения среди стран так называемых «супердержав»[14].

Примечания

- ↑ Определение в Большом юридическом словаре на «Академике» (см. также здесь)

- ↑ Danilović, Vesna. When the Stakes… — С. 27-28

- ↑ 1 2 Bridge, Francis Roy; Bullen, Roger. The Great Powers… — С. 3-4

- ↑ Danilović, Vesna. When the Stakes… — С. 27

- ↑ См. выходные данные здесь (С. 219)

- ↑ Danilović, Vesna. When the Stakes… — С. 228

- ↑ Bridge, Francis Roy; Bullen, Roger. The Great Powers… — С. 1, 4

- ↑ Bridge, Francis Roy; Bullen, Roger. The Great Powers… — С. 4

- ↑ Италии, которую одни источники называют «наименьшей из великих держав» (Danilović, Vesna. P. 38), другие вовсе отказывают в «величии». Так, например, Отто фон Бисмарк, не считавший её великой державой, говорил: «Вся политика умещается в следующую формулу: будь одним из трёх, покуда в мире господствует неустойчивое равновесие пяти держав» (подробнее см. здесь, С. 85-86).

- ↑ Danilović, Vesna. When the Stakes… — С. 229-239

- ↑ Danilović, Vesna. When the Stakes… — С. 26

- ↑ Danilović, Vesna. When the Stakes… — С. 32, 34, 38, 41

- ↑ Лукашук, И. И. Современное право… — С. 65-66

- ↑ 1 2 Danilović, Vesna. When the Stakes… — С. 28

- ↑ Danilović, Vesna. When the Stakes… — С. 225

- ↑ Danilović, Vesna. When the Stakes… — С. 226

- ↑ Лукашук, И. И. Великие и малые… — С. 335-336

- ↑ Danilović, Vesna. When the Stakes… — С. 227

Литература

- Лукашук, И. И. Великие и малые державы // Международное право. — 3-е. — М.: Wolters Kluwer, 2008. — ISBN 978-5-466-00103-7

- Лукашук, И. И. Современное право международных договоров. — М.: Wolters Kluwer, 2006. — Т. II. — ISBN 5446-00208-9

- Bridge, Francis Roy; Bullen, Roger. The Great Powers and the European States System, 1814-1914. — Pearson Education, 2005. — ISBN 0-582-78458-1 (англ.)

- Danilović, Vesna. When the Stakes Are High: Deterrence and Conflict Among Major Powers. — The University of Michigan Press, 2002. — ISBN 0-472-11287-2 (см. также здесь) (англ.)

| |

|

|---|---|

| Типы власти | Экономическая сила · Продовольственная сила · Мягкая сила · Жёсткая сила · Умная сила · Политическая сила (Machtpolitik • Реальная политика) |

| Властные и сравнительные статусы важнейших государств |

Гипердержава · Сверхдержава (Потенциальная сверхдержава · Военная сверхдержава · Ядерная сверхдержава · Космическая сверхдержава · Экономическая сверхдержава · Энергетическая сверхдержава · Демографическая сверхдержава) · Великая держава · Региональная держава · Ближняя держава · Военная держава · Ядерная держава · Космическая держава · Экономическая держава · Энергетическая держава · Демографическая держава |

| Историческая геополитика и гегемония | Исторические сверхдержавы · Исторические державы · Колониальные державы · Европейский «век» · Азиатский «век» · Римский «мир» · Монгольский «мир» · Британский «мир» · Американский «мир» · Советский «мир» · Китайский «мир» · прочие «миры» · Центральные державы · Державы Оси · Союзники |

| Теория и история | Баланс сил (Военно-стратегический паритет) · Историческая держава · Теория перехода державы · Вторая сверхдвержава · Крах сверхдержавы · Распад сверхдержавы · Евроатлантизм |

| Организации и группы | Большая восьмёрка (G8) · Большая двадцатка (G20) · Группа 77 (G77) · БРИКС · Группа одиннадцати · ШОС · НАТО · ОДКБ · АНЗЮС · ОПЕК |

| |

|

|---|---|

| Научные дисциплины и теории | Политология • Сравнительная политология • Теория государства и права • Теория общественного выбора |

| Общие принципы и понятия | Гражданское общество • Правовое государство • Права человека • Разделение властей • Революция • Типы государства • Суверенитет |

| государства по политической силе и влиянию |

Великая держава • Колония • Марионеточное государство • Сателлит • Сверхдержава |

| Виды политики | Геополитика • Внутренняя политика • Внешняя политика |

| Форма государственного устройства | Конфедерация • Унитарное государство • Федерация |

| Социально-политические институты и ветви власти |

Банковская система • Верховная власть • Законодательная власть • Избирательная система • Исполнительная власть • СМИ • Судебная власть |

| Государственный аппарат и органы власти |

Глава государства • Парламент • Правительство |

| Политический режим | Анархия • Авторитаризм • Демократия • Деспотизм • Тоталитаризм |

| Форма государственного правления и политическая система |

Военная диктатура • Диктатура • Монархия • Плутократия • Парламентская республика • Республика • Теократия • Тимократия • Самодержавие • |

| Политическая философия, идеология и доктрина |

Анархизм • Коммунизм • Колониализм • Консерватизм • Космополитизм • Либерализм • Либертарианство • Марксизм • Милитаризм • Монархизм • Нацизм • Национализм • Неоколониализм • Пацифизм • Социализм • Фашизм |

| Избирательная система | Мажоритарная • Пропорциональная • Смешанная |

| Политологи и политические мыслители |

Платон • Аристотель • Макиавелли • Монтескье • Руссо • Бенито Муссолини • Гоббс • Локк • Карл Маркс • Михаил Бакунин • Макс Вебер • Морис Дюверже • Юлиус Эвола • Цицерон • Адольф Гитлер |

| Учебники и известные труды о политике |

«Государство» • «Политика» • «О граде Божьем» • «Государь» • «Левиафан» • «Открытое общество и его враги» |

| См. также | Основные понятия политики |

|

|

| |

|

|---|---|

| География Демография |

Площадь · Максимальные высоты · Минимальные высоты · Население (1900 · 2011 · прогноз) · Плотность населения · Городское население: число городов-миллионеров · Прирост населения · Рождаемость · Смертность · Младенческая смертность |

| Социология | Продолжительность жизни · Качество жизни · Человеческий потенциал · Образование · Грамотность · Общее счастье · МРОТ · Неравенство доходов · Умышленные убийства · Самоубийства · Возраст сексуального согласия · Совершеннолетие · Заключённые · Благотворительность · Потребление: алкоголя (пива) · сигарет · кофе · мобильных телефонов · Интернета (высокоскоростного) · автомобилей |

| Предпринимательство Экономика |

Лёгкость ведения бизнеса · Инновации · Количество патентов · Производство и добыча: нефти · газа · угля · урана · электроэнергии · автомобилей · железной руды · стали · чугуна · бокситов · меди · алюминия · цинка · марганца · висмута · цемента · целлюлозы · бумаги и картона · пшеницы · ржи · риса · ячменя · гречихи · кукурузы · картофеля · молока · рыбы · вина · яблок · Транспорт: железные дороги · автодороги · трубопроводы · внутренние водные пути · морские перевозки · аэропорты · метро |

| Макроэкономика | Глобальная конкурентоспособность · ВВП (номинал): на человека · ВВП (ППС): на человека, прогноз · Бюджет · Внешний долг · Международные резервы · Золотой запас · Запасы нефти · Баланс текущих операций · Торговый баланс · Экспорт · Импорт |

| Политика Армия Космонавтика |

Великие державы · Экономическая свобода · Свобода слова · Демократия · Недееспособность государств · Миролюбие · Вооруженные силы · Военный бюджет · «Ядерный клуб» (ядерное оружие) · «Космический клуб» (ракеты-носители) · Спутники · Космонавты |

| Спорт | ЧМ ФИФА: мужчины · женщины · рейтинг · Мини-футбол · ЧМ по хоккею с шайбой: мужчины · женщины · рейтинг · ЧМ по хоккею с мячом · Кубок Дэвиса |

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale.[2] Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power influence, which may cause middle or small powers to consider the great powers’ opinions before taking actions of their own. International relations theorists have posited that great power status can be characterized into power capabilities, spatial aspects, and status dimensions.[3]

While some nations are widely considered to be great powers, there is considerable debate on the exact criteria of great power status. Historically, the status of great powers has been formally recognized in organizations such as the Congress of Vienna[1][4][5] or the United Nations Security Council.[1][6][7] The United Nations Security Council, NATO Quint, the G7, the BRICs and the Contact Group have all been described as great power concerts.[8][9]

The term «great power» was first used to represent the most important powers in Europe during the post-Napoleonic era. The «Great Powers» constituted the «Concert of Europe» and claimed the right to joint enforcement of the postwar treaties.[10] The formalization of the division between small powers[11] and great powers came about with the signing of the Treaty of Chaumont in 1814. Since then, the international balance of power has shifted numerous times, most dramatically during World War I and World War II. In literature, alternative terms for great power are often world power[12] or major power.[13]

Characteristics[edit]

There are no set or defined characteristics of a great power. These characteristics have often been treated as empirical, self-evident to the assessor.[14] However, this approach has the disadvantage of subjectivity. As a result, there have been attempts to derive some common criteria and to treat these as essential elements of great power status. Danilovic (2002) highlights three central characteristics, which she terms as «power, spatial, and status dimensions,» that distinguish major powers from other states. The following section («Characteristics») is extracted from her discussion of these three dimensions, including all of the citations.[15]

Early writings on the subject tended to judge states by the realist criterion, as expressed by the historian A. J. P. Taylor when he noted that «The test of a great power is the test of strength for war.»[16] Later writers have expanded this test, attempting to define power in terms of overall military, economic, and political capacity.[17] Kenneth Waltz, the founder of the neorealist theory of international relations, uses a set of five criteria to determine great power: population and territory; resource endowment; economic capability; political stability and competence; and military strength.[18] These expanded criteria can be divided into three heads: power capabilities, spatial aspects, and status.[19]

John Mearsheimer defines great powers as those that «have sufficient military assets to put up a serious fight in an all-out conventional war against the most powerful state in the world.»[20]

Power dimensions[edit]

German historian Leopold von Ranke in the mid-19th century attempted to scientifically document the great powers.

As noted above, for many, power capabilities were the sole criterion. However, even under the more expansive tests, power retains a vital place.

This aspect has received mixed treatment, with some confusion as to the degree of power required. Writers have approached the concept of great power with differing conceptualizations of the world situation, from multi-polarity to overwhelming hegemony. In his essay, ‘French Diplomacy in the Postwar Period’, the French historian Jean-Baptiste Duroselle spoke of the concept of multi-polarity: «A Great power is one which is capable of preserving its own independence against any other single power.»[21]

This differed from earlier writers, notably from Leopold von Ranke, who clearly had a different idea of the world situation. In his essay ‘The Great Powers’, written in 1833, von Ranke wrote: «If one could establish as a definition of a Great power that it must be able to maintain itself against all others, even when they are united, then Frederick has raised Prussia to that position.»[22] These positions have been the subject of criticism.[clarification needed][19]

In 2011 the U.S. had 10 major strengths according to Chinese scholar Peng Yuan, the director of the Institute of American Studies of the China Institutes for Contemporary International Studies.[23]

- 1. Population, geographic position, and natural resources.

- 2. Military muscle.

- 3. High technology and education.

- 4. Cultural/soft power.

- 5. Cyber power.

- 6. Allies, the United States having more than any other state.

- 7. Geopolitical strength, as embodied in global projection forces.

- 8. Intelligence capabilities, as demonstrated by the killing of Osama bin Laden.

- 9. Intellectual power, fed by a plethora of U.S. think tanks and the “revolving door” between research institutions and government.

- 10. Strategic power, the United States being the world’s only country with a truly global strategy.

However he also noted where the U.S. had recently slipped:

- 1. Political power, as manifested by the breakdown of bipartisanship.

- 2. Economic power, as illustrated by the post-2007 slowdown.

- 3. Financial power, given intractable deficits and rising debt.

- 4. Social power, as weakened by societal polarization.

- 5. Institutional power, since the United States can no longer dominate global institutions

Spatial dimension[edit]

All states have a geographic scope of interests, actions, or projected power. This is a crucial factor in distinguishing a great power from a regional power; by definition, the scope of a regional power is restricted to its region. It has been suggested that a great power should be possessed of actual influence throughout the scope of the prevailing international system. Arnold J. Toynbee, for example, observes that «Great power may be defined as a political force exerting an effect co-extensive with the widest range of the society in which it operates. The Great powers of 1914 were ‘world-powers’ because Western society had recently become ‘world-wide’.»[24]

Other suggestions have been made that a great power should have the capacity to engage in extra-regional affairs and that a great power ought to be possessed of extra-regional interests, two propositions which are often closely connected.[25]

Status dimension[edit]

Formal or informal acknowledgment of a nation’s great power status has also been a criterion for being a great power. As political scientist George Modelski notes, «The status of Great power is sometimes confused with the condition of being powerful. The office, as it is known, did in fact evolve from the role played by the great military states in earlier periods… But the Great power system institutionalizes the position of the powerful state in a web of rights and obligations.»[26]

This approach restricts analysis to the epoch following the Congress of Vienna at which great powers were first formally recognized.[19] In the absence of such a formal act of recognition it has been suggested that great power status can arise by implication by judging the nature of a state’s relations with other great powers.[27]

A further option is to examine a state’s willingness to act as a great power.[27] As a nation will seldom declare that it is acting as such, this usually entails a retrospective examination of state conduct. As a result, this is of limited use in establishing the nature of contemporary powers, at least not without the exercise of subjective observation.

Other important criteria throughout history are that great powers should have enough influence to be included in discussions of contemporary political and diplomatic questions, and exercise influence on the outcome and resolution. Historically, when major political questions were addressed, several great powers met to discuss them. Before the era of groups like the United Nations, participants of such meetings were not officially named but rather were decided based on their great power status. These were conferences that settled important questions based on major historical events.

History[edit]

Different sets of great, or significant, powers have existed throughout history. An early reference to great powers is from the 3rd century, when the Persian prophet Mani described Rome, China, Aksum, and Persia as the four greatest kingdoms of his time.[28] During the Napoleonic wars in Europe American diplomat James Monroe observed that, «The respect which one power has for another is in exact proportion of the means which they respectively have of injuring each other.»[29] The term «great power» first appears at the Congress of Vienna in 1815.[19][30] The Congress established the Concert of Europe as an attempt to preserve peace after the years of Napoleonic Wars.

Lord Castlereagh, the British foreign secretary, first used the term in its diplomatic context, writing on 13 February 1814: «there is every prospect of the Congress terminating with a general accord and Guarantee between the Great powers of Europe, with a determination to support the arrangement agreed upon, and to turn the general influence and if necessary the general arms against the Power that shall first attempt to disturb the Continental peace.»[10]

The Congress of Vienna consisted of five main powers: the Austrian Empire, France, Prussia, Russia, and Great Britain. These five primary participants constituted the original great powers as we know the term today.[19] Other powers, such as Spain, Portugal, and Sweden, which were great powers during the 17th century and the earlier 18th century, were consulted on certain specific issues, but they were not full participants.

After the Congress of Vienna, Great Britain emerged as the pre-eminent global hegemon, due to it being the first nation to industrialize, possessing the largest navy, and the extent of its overseas empire, which ushered in a century of Pax Britannica. The balance of power between the Great Powers became a major influence in European politics, prompting Otto von Bismarck to say «All politics reduces itself to this formula: try to be one of three, as long as the world is governed by the unstable equilibrium of five great powers.»[31]

Over time, the relative power of these five nations fluctuated, which by the dawn of the 20th century had served to create an entirely different balance of power. Great Britain and the new German Empire (from 1871), experienced continued economic growth and political power.[32] Others, such as Russia and Austria-Hungary, stagnated.[33] At the same time, other states were emerging and expanding in power, largely through the process of industrialization. These countries seeking to attain great power status were: Italy after the Risorgimento era, Japan during the Meiji era, and the United States after its civil war. By 1900, the balance of world power had changed substantially since the Congress of Vienna. The Eight-Nation Alliance was an alliance of eight nations created in response to the Boxer Rebellion in China. It formed in 1900 and consisted of the five Congress powers plus Italy, Japan, and the United States, representing the great powers at the beginning of the 20th century.[34]

World Wars[edit]

Shifts of international power have most notably occurred through major conflicts.[35] The conclusion of World War I and the resulting treaties of Versailles, St-Germain, Neuilly, Trianon, and Sèvres made Great Britain, France, Italy, Japan, and the United States the chief arbiters of the new world order.[36] The German Empire was defeated, Austria-Hungary was divided into new, less powerful states and the Russian Empire fell to revolution. During the Paris Peace Conference, the «Big Four» – Great Britain, France, Italy, and the United States – controlled the proceedings and outcome of the treaties than Japan. The Big Four were the architects of the Treaty of Versailles which was signed by Germany; the Treaty of St. Germain, with Austria; the Treaty of Neuilly, with Bulgaria; the Treaty of Trianon, with Hungary; and the Treaty of Sèvres, with the Ottoman Empire. During the decision-making of the Treaty of Versailles, Italy pulled out of the conference because a part of its demands were not met and temporarily left the other three countries as the sole major architects of that treaty, referred to as the «Big Three».[37]

The status of the victorious great powers were recognised by permanent seats at the League of Nations Council, where they acted as a type of executive body directing the Assembly of the League. However, the council began with only four permanent members – Great Britain, France, Italy, and Japan – because the United States, meant to be the fifth permanent member, never joined the League. Germany later joined after the Locarno Treaties, which made it a member of the League of Nations, and later left (and withdrew from the League in 1933); Japan left, and the Soviet Union joined.

When World War II started in 1939, it divided the world into two alliances: the Allies (initially the United Kingdom and France, China, followed in 1941 by the Soviet Union and the United States) and the Axis powers (Germany, Italy, and Japan).[38][nb 1] During World War II, the U.S., U.K., USSR, and China were referred as a «trusteeship of the powerful»[39] and were recognized as the Allied «Big Four» in Declaration by United Nations in 1942.[40] These four countries were referred as the «Four Policemen» of the Allies and considered as the primary victors of World War II.[41] The importance of France was acknowledged by their inclusion, along with the other four, in the group of countries allotted permanent seats in the United Nations Security Council.

Since the end of the World Wars, the term «great power» has been joined by a number of other power classifications. Foremost among these is the concept of the superpower, used to describe those nations with overwhelming power and influence in the rest of the world. It was first coined in 1944 by William T. R. Fox[42] and according to him, there were three superpowers: Great Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union. But after World War II Britain lost its superpower status.[43] The term middle power has emerged for those nations which exercise a degree of global influence but are insufficient to be decisive on international affairs. Regional powers are those whose influence is generally confined to their region of the world.

Cold War[edit]

The Cold War was a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc, which began following World War II. The term «cold» is used because there was no large-scale fighting directly between the two superpowers, but they each supported major regional conflicts known as proxy wars. The conflict was based around the ideological and geopolitical struggle for global influence by these two superpowers, following their temporary alliance and victory against Nazi Germany in 1945.[44]

During the Cold War, Japan, France, the United Kingdom and West Germany rebuilt their economies. France and the United Kingdom maintained technologically advanced armed forces with power projection capabilities and maintain large defense budgets to this day. Yet, as the Cold War continued, authorities began to question if France and the United Kingdom could retain their long-held statuses as great powers.[45] China, with the world’s largest population, has slowly risen to great power status, with large growth in economic and military power in the post-war period. After 1949, the Republic of China began to lose its recognition as the sole legitimate government of China by the other great powers, in favour of the People’s Republic of China. Subsequently, in 1971, it lost its permanent seat at the UN Security Council to the People’s Republic of China.

Aftermath of the Cold War[edit]

China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom, and the United States are often referred to as great powers by academics due to «their political and economic dominance of the global arena».[46] These five nations are the only states to have permanent seats with veto power on the UN Security Council. They are also the only state entities to have met the conditions to be considered «Nuclear Weapons States» under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, and maintain military expenditures which are among the largest in the world.[47] However, there is no unanimous agreement among authorities as to the current status of these powers or what precisely defines a great power. For example, sources have at times referred to China,[48] France,[49] Russia[50][51][52] and the United Kingdom[49] as middle powers.

Following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, its UN Security Council permanent seat was transferred to the Russian Federation in 1991, as its largest successor state. The newly formed Russian Federation emerged on the level of a great power, leaving the United States as the only remaining global superpower[nb 2] (although some support a multipolar world view).

Japan and Germany are great powers too, though due to their large advanced economies (having the third and fourth largest economies respectively) rather than their strategic and hard power capabilities (i.e., the lack of permanent seats and veto power on the UN Security Council or strategic military reach).[53][54][55] Germany has been a member together with the five permanent Security Council members in the P5+1 grouping of world powers. Like China, France, Russia, and the United Kingdom; Germany and Japan have also been referred to as middle powers.[56][57][58][59][60][61][62]

In his 2014 publication Great Power Peace and American Primacy, Joshua Baron considers China, France, Russia, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States as the current great powers.[63]

Italy has been referred to as a great power by a number of academics and commentators throughout the post WWII era.[64][65][66][67][68] The American international legal scholar Milena Sterio writes:

The great powers are super-sovereign states: an exclusive club of the most powerful states economically, militarily, politically and strategically. These states include veto-wielding members of the United Nations Security Council (United States, United Kingdom, France, China, and Russia), as well as economic powerhouses such as Germany, Italy and Japan.[65]

Sterio also cites Italy’s status in the Group of Seven (G7) and the nation’s influence in regional and international organizations for its status as a great power.[65] Italy has been a member together with the five permanent Security Council members plus Germany in the International Support Group for Lebanon (ISG)[69][70][71] grouping of world powers. Some analysts assert that Italy is an «intermittent» or the «least of the great powers»,[72][73] while some others believe Italy is a middle or regional power.[74][75][76]

In addition to these contemporary great powers mentioned above, Zbigniew Brzezinski[77] and Mohan Malik consider India to be a great power too.[78] Although unlike the contemporary great powers who have long been considered so, India’s recognition among authorities as a great power is comparatively recent.[78] However, there is no collective agreement among observers as to the status of India, for example, a number of academics believe that India is emerging as a great power,[79] while some believe that India remains a middle power.[80][81][82]

The United Nations Security Council, NATO Quint, the G7, the BRICs and the Contact Group have all been described as great power concerts.[8][83][84][85][86][87]

A 2017 study by the Hague Centre for Strategic Studies qualified China, Europe, India, Japan, Russia and the United States as the current great powers.[88]

Emerging powers[edit]

With continuing European integration, the European Union is increasingly being seen as a great power in its own right,[89] with representation at the WTO and at G7 and G-20 summits. This is most notable in areas where the European Union has exclusive competence (i.e. economic affairs). It also reflects a non-traditional conception of Europe’s world role as a global «civilian power», exercising collective influence in the functional spheres of trade and diplomacy, as an alternative to military dominance.[90] The European Union is a supranational union and not a sovereign state and does not have its own foreign affairs or defence policies; these remain largely with the member states, which include France, Germany and, before Brexit, the United Kingdom (referred to collectively as the «EU three»).[77]

Brazil and India are widely regarded as emerging powers with the potential to be great powers.[1] Political scientist Stephen P. Cohen asserts that India is an emerging power, but highlights that some strategists consider India to be already a great power.[91] Some academics such as Zbigniew Brzezinski and David A. Robinson already regard India as a major or great power.[77][92]

Former British Ambassador to Brazil, Peter Collecott identifies that Brazil’s recognition as a potential great and superpower largely stems from its own national identity and ambition.[93] Professor Kwang Ho Chun feels that Brazil will emerge as a great power with an important position in some spheres of influence.[94] Others suggest India and Brazil may even have the potential to emerge as a superpower.[95][94]

Permanent membership of the UN Security Council is widely regarded as being a central tenet of great power status in the modern world; Brazil, Germany, India and Japan form the G4 nations which support one another (and have varying degrees of support from the existing permanent members) in becoming permanent members.[96] The G4 is opposed by the Italian-led Uniting for Consensus group. There are however few signs that reform of the Security Council will happen in the near future.[citation needed]

Israel[97][98] and Iran[99][98] are also mentioned in the context of great powers.

Hierarchy of great powers[edit]

The political scientist, geo-strategist, and former US National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski appraised the current standing of the great powers in his 2012 publication Strategic Vision: America and the Crisis of Global Power. In relation to great powers, he makes the following points:

The United States is still preeminent but the legitimacy, effectiveness, and durability of its leadership is increasingly questioned worldwide because of the complexity of its internal and external challenges. … The European Union could compete to be the world’s number two power, but this would require a more robust political union, with a common foreign policy and a shared defense capability. … In contrast, China’s remarkable economic momentum, its capacity for decisive political decisions motivated by clearheaded and self-centered national interest, its relative freedom from debilitating external commitments, and its steadily increasing military potential coupled with the worldwide expectation that soon it will challenge America’s premier global status justify ranking China just below the United States in the current international hierarchy. … A sequential ranking of other major powers beyond the top two would be imprecise at best. Any list, however, has to include Russia, Japan, and India, as well as the EU’s informal leaders: Great Britain, Germany, and France.[77]

According to a 2014 report of the Hague Centre for Strategic Studies:

Great Powers… are disproportionately engaged in alliances and wars, and their diplomatic weight is often cemented by their strong role in international institutions and forums. This unequal distribution of power and prestige leads to «a set of rights and rules governing interactions among states» that sees incumbent powers competing to maintain the status quo and keep their global influence. In today’s international system, there are four great powers that fit this definition: the United States (US), Russia, China and the European Union (whereby the EU is considered to be the sum of its parts). If we distil from this description of great power attributes and capabilities a list of criteria, it is clear why these four powers dominate the international security debate. The possession of superior military and economic capabilities can be translated into measurements such as military expenditure and GDP, and nowhere are the inherent privileges of great powers more visible than in the voting mechanisms of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC), where five permanent members have an overriding veto. The top ten countries ranked on the basis of military expenditures correspond almost exactly with the top ten countries ranked on the basis of GDP with the exception of Saudi Arabia which is surpassed by Brazil. Notably, each country with a permanent seat on the UNSC also finds itself in the top ten military and economic powers. When taken as the sum of its parts, the EU scores highest in terms of economic wealth and diplomatic weight in the UNSC. This is followed closely by the US, which tops the military expenditures ranking, and then Russia and China, both of which exert strong military, economic, and diplomatic influence in the international system.[100]

See also[edit]

- Big Four (Western Europe)

- G8

- Indo-Pacific

- List of modern great powers

- List of medieval great powers

- List of ancient great powers

- Power (international relations)

- Precedence among European monarchies

- International relations (1648–1814)

- International relations (1814–1919)

- Diplomatic history of World War I

- International relations (1919–1939)

- Diplomatic history of World War II

- History of United States foreign policy

- History of French foreign relations

- History of German foreign policy

- Foreign policy of the Russian Empire

- Foreign relations of the Soviet Union

- Historiography of the British Empire

- History of the foreign relations of the United Kingdom

Notes[edit]

- ^ Even though the book The Economics of World War II lists seven great powers at the start of 1939 (Great Britain, Japan, France, Italy, Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and the United States), it focuses only on six of them, because France surrendered shortly after the war began.[citation needed]

- ^ The fall of the Berlin Wall and the breakup of the Soviet Union left the United States as the only remaining superpower in the 1990s.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d

Peter Howard (2008). «Great Powers». Encarta. MSN. Archived from the original on 31 October 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2008. - ^ Böhler, Ron (9 October 2017). What is a Great Power? A Concept and Its Meaning for Understanding International Relations. ISBN 9783668538665.

- ^ Iver B. Neumann, «Russia as a great power, 1815–2007.» Journal of International Relations and Development 11.2 (2008): 128–151. online

- ^ Fueter, Eduard (1922). World history, 1815–1930. United States: Harcourt, Brace and Company. pp. 25–28, 36–44. ISBN 1-58477-077-5.

- ^ Danilovic, Vesna. «When the Stakes Are High – Deterrence and Conflict among Major Powers», University of Michigan Press (2002), pp 27, 225–228 (PDF chapter downloads) Archived 30 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine (PDF copy) .

- ^ Louden, Robert (2007). The world we want. United States of America: Oxford University Press US. p. 187. ISBN 978-0195321371.

- ^ T. V. Paul; James J. Wirtz; Michel Fortmann (2005). «Great+power» Balance of Power. United States: State University of New York Press, 2005. pp. 59, 282. ISBN 0791464016. Accordingly, the great powers after the Cold War are Britain, China, France, Germany, Japan, Russia and the United States p. 59

- ^ a b Gaskarth, Jamie (11 February 2015). Rising Powers, Global Governance and Global Ethics. Routledge. p. 182. ISBN 978-1317575115.

- ^ Richard Gowan; Bruce D. Jones; Shepard Forman, eds. (2010). Cooperating for peace and security: evolving institutions and arrangements in a context of changing U.S. security policy (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge [U.K.]: Cambridge University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0521889476.

- ^ a b Charles Webster, (ed), British Diplomacy 1813–1815: Selected Documents Dealing with the Reconciliation of Europe, (1931), p. 307.

- ^ Toje, A. (2010). The European Union as a small power: After the post-Cold War. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ «World power Definition & Meaning | Dictionary.com».

- ^ «Dictionary – Major power». reference.com.

- ^ Waltz, Kenneth N (1979). Theory of International Politics. McGraw-Hill. p. 131. ISBN 0-201-08349-3.

- ^ Danilovic, Vesna (2002). When the Stakes Are High – Deterrence and Conflict among Major Powers. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11287-6. [1]

- ^ Taylor, Alan JP (1954). The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918. Oxford: Clarendon. p. xxiv. ISBN 0-19-881270-1.

- ^ Organski, AFK – World Politics, Knopf (1958)

- ^ Waltz, Kenneth N. (1993). «The Emerging Structure of International Politics» (PDF). International Security. 18 (2): 50. doi:10.2307/2539097. JSTOR 2539097. S2CID 154473957 – via International Relations Exam Database.

- ^ a b c d e Danilovic, Vesna. «When the Stakes Are High – Deterrence and Conflict among Major Powers», University of Michigan Press (2002), pp 27, 225–230 [2].

- ^ Mearsheimer, John (2001). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. W. W. Norton. p. 5.

- ^ contained on page 204 in: Kertesz and Fitsomons (eds) – Diplomacy in a Changing World, University of Notre Dame Press (1960)

- ^ Iggers and von Moltke «In the Theory and Practice of History», Bobbs-Merrill (1973)

- ^ Quoted in Josef Joffe, The Myth of America’s Decline: Politics, Economics, and a Half Century of False Prophecies (2014) ch. 7.

- ^ Toynbee, Arnold J (1926). The World After the Peace Conference. Humphrey Milford and Oxford University Press. p. 4. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- ^ Stoll, Richard J – State Power, World Views, and the Major Powers, Contained in: Stoll and Ward (eds) – Power in World Politics, Lynne Rienner (1989)

- ^ Modelski, George (1972). Principles of World Politics. Free Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-02-921440-4.

- ^ a b Domke, William K – Power, Political Capacity, and Security in the Global System, Contained in: Stoll and Ward (eds) – Power in World Politics, Lynn Rienner (1989)

- ^ «Obelisk points to ancient Ethiopian glory». 11 April 2005.

- ^ Tim McGrath, James Monroe: A Life (2020) p 44.

- ^ Fueter, Eduard (1922). World history, 1815–1920. United States of America: Harcourt, Brace and Company. pp. 25–28, 36–44. ISBN 1584770775.

- ^ Bartlett, C. J. (1996). Peace, War and the European Powers, 1814–1914. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 106. ISBN 9780312161385.

- ^ «Multi-polarity vs Bipolarity, Subsidiary hypotheses, Balance of Power». University of Rochester. Archived from the original (PPT) on 16 June 2007. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ Tonge, Stephen. «European History Austria-Hungary 1870–1914«. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ Dallin, David (30 November 2006). The Rise of Russia in Asia. Read Books. ISBN 978-1-4067-2919-1.

- ^ Power Transitions as the cause of war.

- ^ Globalization and Autonomy by Julie Sunday, McMaster University. Archived 15 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ MacMillan, Margaret (2003). Paris 1919. Random House Trade. pp. 36, 306, 431. ISBN 0-375-76052-0.

- ^ Harrison, M (2000) M1 The Economics of World War II: Six Great Powers in International Comparison, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Doenecke, Justus D.; Stoler, Mark A. (2005). Debating Franklin D. Roosevelt’s foreign policies, 1933–1945. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-9416-X.

- ^ Hoopes, Townsend, and Douglas Brinkley. FDR and the Creation of the U.N. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-300-06930-3.

- ^ Sainsbury, Keith (1986). The Turning Point: Roosevelt, Stalin, Churchill, and Chiang Kai-Shek, 1943: The Moscow, Cairo, and Teheran Conferences. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-215858-1.

- ^ The Superpowers: The United States, Britain, and the Soviet Union – Their Responsibility for Peace (1944), written by William T.R. Fox

- ^ Peden, 2012.

- ^ Sempa, Francis (12 July 2017). Geopolitics: From the Cold War to the 21st Century. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-51768-3.

- ^ Holmes, John. «Middle Power». The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 3 March 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ Yasmi Adriansyah, ‘Questioning Indonesia’s place in the world’, Asia Times (20 September 2011): ‘Though there are still debates on which countries belong to which category, there is a common understanding that the GP [great power] countries are the United States, China, United Kingdom, France, and Russia. Besides their political and economic dominance of the global arena, these countries have a special status in the United Nations Security Council with their permanent seats and veto rights.’

- ^ «The 15 countries with the highest military expenditure in 2012 (table)». Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ^ Gerald Segal, Does China Matter?, Foreign Affairs (September/October 1999).

- ^ a b P. Shearman, M. Sussex, European Security After 9/11(Ashgate, 2004) – According to Shearman and Sussex, both the UK and France were great powers now reduced to middle power status.

- ^ Neumann, Iver B. (2008). «Russia as a great power, 1815–2007». Journal of International Relations and Development. 11 (2): 128–151 [p. 128]. doi:10.1057/jird.2008.7.

As long as Russia’s rationality of government deviates from present-day hegemonic neo-liberal models by favouring direct state rule rather than indirect governance, the West will not recognize Russia as a fully-fledged great power.

- ^ Garnett, Sherman (6 November 1995). «Russia ponders its nuclear options». Washington Times. p. 2.

Russia must deal with the rise of other middle powers in Eurasia at a time when it is more of a middle power itself.

- ^ Kitney, Geoff (25 March 2000). «Putin It To The People». Sydney Morning Herald. p. 41.

The Council for Foreign and Defence Policy, which includes senior figures believed to be close to Putin, will soon publish a report saying Russia’s superpower days are finished and that the country should settle for being a middle power with a matching defence structure.

- ^ T.V. Paul; James Wirtz; Michel Fortmann (8 September 2004). Balance of Power: Theory and Practice in the 21st century. Stanford University Press. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-0-8047-5017-2.

- ^ Worldcrunch.com (28 November 2011). «Europe’s Superpower: Germany Is The New Indispensable (And Resented) Nation». Worldcrunch.com. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ Winder, Simon (19 November 2011). «Germany: The reluctant superpower». The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ Sperling, James (2001). «Neither Hegemony nor Dominance: Reconsidering German Power in Post Cold-War Europe». British Journal of Political Science. 31 (2): 389–425. doi:10.1017/S0007123401000151.

- ^ Max Otte; Jürgen Greve (2000). A Rising Middle Power?: German Foreign Policy in Transformation, 1989–1999. Germany. p. 324. ISBN 0-312-22653-5.

- ^ Er LP (2006) Japan’s Human Security Rolein Southeast Asia

- ^ «Merkel as a world star — Germany’s place in the world», The Economist (18 November 2006), p. 27: «Germany, says Volker Perthes, director of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, is now pretty much where it belongs: squarely at the centre. Whether it wants to be or not, the country is a Mittelmacht, or middle power.»

- ^ Susanna Vogt, «Germany and the G20», in Wilhelm Hofmeister, Susanna Vogt, G20: Perceptions and Perspectives for Global Governance (Singapore: 19 October 2011), p. 76, citing Thomas Fues and Julia Leininger (2008): «Germany and the Heiligendamm Process», in Andrew Cooper and Agata Antkiewicz (eds.): Emerging Powers in Global Governance: Lessons from the Heiligendamm Process, Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, p. 246: «Germany’s motivation for the initiative had been ‘… driven by a combination of leadership qualities and national interests of a middle power with civilian characteristics’.»

- ^ «Change of Great Powers», in Global Encyclopaedia of Political Geography, by M.A. Chaudhary and Guatam Chaudhary (New Delhi, 2009.), p. 101: «Germany is considered by experts to be an economic power. It is considered as a middle power in Europe by Chancellor Angela Merkel, former President Johannes Rau and leading media of the country.»

- ^ Susanne Gratius, Is Germany still a EU-ropean power?, FRIDE Policy Brief, No. 115 (February 2012), pp. 1–2: «Being the world’s fourth largest economic power and the second largest in terms of exports has not led to any greater effort to correct Germany’s low profile in foreign policy … For historic reasons and because of its size, Germany has played a middle-power role in Europe for over 50 years.»

- ^ Baron, Joshua (22 January 2014). Great Power Peace and American Primacy: The Origins and Future of a New International Order. United States: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137299482.

- ^ Canada Among Nations, 2004: Setting Priorities Straight. McGill-Queen’s Press – MQUP. 17 January 2005. p. 85. ISBN 0773528369. («The United States is the sole world’s superpower. France, Italy, Germany and the United Kingdom are great powers«)

- ^ a b c Sterio, Milena (2013). The right to self-determination under international law: «selfistans», secession and the rule of the great powers. Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. xii (preface). ISBN 978-0415668187. («The great powers are super-sovereign states: an exclusive club of the most powerful states economically, militarily, politically and strategically. These states include veto-wielding members of the United Nations Security Council (United States, United Kingdom, France, China, and Russia), as well as economic powerhouses such as Germany, Italy and Japan.«)

- ^ Transforming Military Power since the Cold War: Britain, France, and the United States, 1991–2012. Cambridge University Press. 2013. p. 224. ISBN 978-1107471498. (During the Kosovo War (1998) «…Contact Group consisting of six great powers (the United states, Russia, France, Britain, Germany and Italy).«)

- ^ Why are Pivot States so Pivotal? The Role of Pivot States in Regional and Global Security. Netherlands: The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. 2014. p. Table on page 10 (Great Power criteria). Archived from the original on 11 October 2016. Retrieved 14 June 2016.

- ^ Kuper, Stephen. «Clarifying the nation’s role strengthens the impact of a National Security Strategy 2019«. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

Traditionally, great powers have been defined by their global reach and ability to direct the flow of international affairs. There are a number of recognised great powers within the context of contemporary international relations – with Great Britain, France, India and Russia recognised as nuclear-capable great powers, while Germany, Italy and Japan are identified as conventional great powers

- ^ «Lebanon – Ministerial meeting of the International Support Group (Paris, 08.12.17)».

- ^ «Big power grouping urges Lebanon to uphold policy on steering clear of war». Reuters. 10 May 2018.

- ^ «Members of the International Support Group for Lebanon Meet with Prime Minister Designate Saad Hariri» (PDF) (Press release). unmisssions.org. 11 July 2018. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Dimitris Bourantonis; Marios Evriviades, eds. (1997). A United Nations for the twenty-first century: peace, security, and development. Boston: Kluwer Law International. p. 77. ISBN 9041103120. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ Italy: 150 years of a small great power, eurasia-rivista.org, 21 December 2010

- ^ Verbeek, Bertjan; Giacomello, Giampiero (2011). Italy’s foreign policy in the twenty-first century: the new assertiveness of an aspiring middle power. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-4868-6.

- ^ «Operation Alba may be considered one of the most important instances in which Italy has acted as a regional power, taking the lead in executing a technically and politically coherent and determined strategy.» See Federiga Bindi, Italy and the European Union (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2011), p. 171.

- ^ «Italy plays a prominent role in European and global military, cultural and diplomatic affairs. The country’s European political, social and economic influence make it a major regional power.» See Italy: Justice System and National Police Handbook, Vol. 1 (Washington, D.C.: International Business Publications, 2009), p. 9.

- ^ a b c d Strategic Vision: America & the Crisis of Global Power by Zbigniew Brzezinski, pp. 43–45. Published 2012.

- ^ a b Malik, Mohan (2011). China and India: Great Power Rivals. United States: FirstForumPress. ISBN 978-1935049418.

- ^ Brewster, David (2012). India as an Asia Pacific Power. United States: Routledge. ISBN 978-1136620089.

- ^ Charalampos Efstathopoulosa, ‘Reinterpreting India’s Rise through the Middle Power Prism’, Asian Journal of Political Science, Vol. 19, Issue 1 (2011), p. 75: ‘India’s role in the contemporary world order can be optimally asserted by the middle power concept. The concept allows for distinguishing both strengths and weakness of India’s globalist agency, shifting the analytical focus beyond material-statistical calculations to theorise behavioural, normative and ideational parameters.’

- ^ Robert W. Bradnock, India’s Foreign Policy since 1971 (The Royal Institute for International Affairs, London: Pinter Publishers, 1990), quoted in Leonard Stone, ‘India and the Central Eurasian Space’, Journal of Third World Studies, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2007, p. 183: «The U.S. is a superpower whereas India is a middle power. A superpower could accommodate another superpower because the alternative would be equally devastating to both. But the relationship between a superpower and a middle power is of a different kind. The former does not need to accommodate the latter while the latter cannot allow itself to be a satellite of the former.»

- ^ Jan Cartwright, ‘India’s Regional and International Support for Democracy: Rhetoric or Reality?’, Asian Survey, Vol. 49, No. 3 (May/June 2009), p. 424: ‘India’s democratic rhetoric has also helped it further establish its claim as being a rising «middle power.» (A «middle power» is a term that is used in the field of international relations to describe a state that is not a superpower but still wields substantial influence globally. In addition to India, other «middle powers» include, for example, Australia and Canada.)’

- ^ Richard Gowan; Bruce D. Jones; Shepard Forman, eds. (2010). Cooperating for peace and security: evolving institutions and arrangements in a context of changing U.S. security policy (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge [U.K.]: Cambridge University Press. p. 236. ISBN 978-0521889476.

- ^ The Routledge Handbook of Transatlantic Security. Routledge. 2 July 2010. ISBN 978-1136936074. (see section on ‘The G6/G7: great power governance’)

- ^ Contemporary Concert Diplomacy: The Seven-Power Summit as an International Concert, Professor John Kirton

- ^ Penttilä, Risto (17 June 2013). The Role of the G8 in International Peace and Security. Routledge. pp. 17–32. ISBN 978-1136053528. (The G8 as a Concert of Great Powers)

- ^ Tables of Sciences Po and Documentation Francaise: Russia y las grandes potencias and

G8 et Chine (2004) - ^ Sweijs, T.; De Spiegeleire, S.; de Jong, S.; Oosterveld, W.; Roos, H.; Bekkers, F.; Usanov, A.; de Rave, R.; Jans, K. (2017). Volatility and friction in the age of disintermediation. The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies. p. 43. ISBN 978-94-92102-46-1. Retrieved 29 April 2022.

We qualify the following states as great powers: China, Europe, India, Japan, Russia and the United States.

- ^ Buzan, Barry (2004). The United States and the Great Powers. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Polity Press. p. 70. ISBN 0-7456-3375-7.

- ^ Veit Bachmann and James D Sidaway, «Zivilmacht Europa: A Critical Geopolitics of the European Union as a Global Power», Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Jan. 2009), pp. 94–109.

- ^ «India: Emerging Power», by Stephen P. Cohen, p. 60

- ^ «India’s Rise as a Great Power, Part One: Regional and Global Implications». Futuredirections.org.au. 7 July 2011. Archived from the original on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- ^ Peter Collecott (29 October 2011). «Brazil’s Quest for Superpower Status». The Diplomatic Courier. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- ^ a b Kwang Ho Chun (2013). The BRICs Superpower Challenge: Foreign and Security Policy Analysis. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1-4094-6869-1. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- ^ Robyn Meredith (2007). The Elephant and the Dragon: The Rise of India and China and What it Means for All of Us. W.W Norton and Company. ISBN 978-0-393-33193-6.

- ^ Sharma, Rajeev (27 September 2015). «India pushes the envelope at G4 Summit: PM Modi tells UNSC to make space for largest democracies». First Post. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Keeley, Walter Russell Mead & Sean. «The Eight Great Powers of 2017 – by Walter Russell Mead Sean Keeley». Retrieved 6 November 2018.

This year there’s a new name on our list of the Eight Greats: Israel. A small country in a chaotic part of the world, Israel is a rising power with a growing impact on world affairs. […] Three factors are powering Israel’s rise: economic developments, the regional crisis, and diplomatic ingenuity. […] [B]eyond luck, Israel’s newfound clout on the world stage comes from the rise of industrial sectors and technologies that good Israeli schools, smart Israeli policies and talented Israeli thinkers and entrepreneurs have built up over many years.

- ^ a b «Power Rankings». usnews.com. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ Keeley, Walter Russell Mead & Sean. «The Eight Great Powers of 2017 – by Walter Russell Mead Sean Keeley». Retrieved 6 November 2018.

The proxy wars between Saudi Arabia and Iran continued unabated throughout 2016, and as we enter the new year Iran has confidently taken the lead. […] Meanwhile, the fruits of the nuclear deal continued to roll in: high-profile deals with Boeing and Airbus sent the message that Iran was open for business, while Tehran rapidly ramped up its oil output to pre-sanctions levels. […] 2017 may be a more difficult year for Tehran […] the Trump administration seems more concerned about rebuilding ties with traditional American allies in the region than in continuing Obama’s attempt to reach an understanding with Iran.

- ^ Why are Pivot states so Pivotal? Archived 2016-02-11 at the Wayback Machine, hcss.nl, 2014

Further reading[edit]

- Abbenhuis, Maartje. An Age of Neutrals Great Power Politics, 1815–1914 (2014) excerpt

- Allison, Graham. «The New Spheres of Influence: Sharing the Globe with Other Great Powers.» Foreign Affairs 99 (2020): 30+ online

- Bridge, Roy, and Roger Bullen, eds. The Great Powers and the European States System 1814–1914 (2nd ed. 2004) excerpt

- Brooks, Stephen G., and William C. Wohlforth. «The rise and fall of the great powers in the twenty-first century: China’s rise and the fate of America’s global position.» International Security 40.3 (2016): 7–53. online

- Dickson, Monday E. Dickson. «Great Powers and the Quest for Hegemony in the Contemporary International System.» Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 6.6 (2019): 168–176. online

- Duroselle, Jean-Baptiste (January 2004). France and the Nazi Threat: The Collapse of French Diplomacy 1932–1939. Enigma Books. ISBN 1-929631-15-4.

- Edelstein, David M. Over the Horizon: Time, Uncertainty, and the Rise of Great Powers (Cornell UP, 2017).

- Efremova, Ksenia. «Small States in Great Power Politics: Understanding the» Buffer Effect».» Central European Journal of International & Security Studies 13.1 (2019) online.

- Eloranta, Jari, Eric Golson, Peter Hedberg, and Maria Cristina Moreira, eds. Small and Medium Powers in Global History: Trade, Conflicts, and Neutrality from the Eighteenth to the Twentieth Centuries (Routledge, 2018) 240 pp. online review

- Joffe, Josef. The Myth of America’s Decline: Politics, Economics, and a Half Century of False Prophecies (2014) online

- Joffe, Josef. The Future of the great powers (1998) online

- Kassab, Hanna Samir. Grand strategies of weak states and great powers (Springer, 2017).

- Kennedy, Paul. The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers (1987) online

- Langer, William, ed. (1973) An Encyclopedia Of World History (1948 And later editions) online

- Stearns, Peter, ed. The Encyclopedia of World History (2007), 1245pp; update of Langer

- Mckay, Derek; H.M. Scott (1983). The Rise of the Great Powers 1648 – 1815. Pearson. ISBN 9781317872849.

- Maass, Matthias. Small states in world politics: The story of small state survival, 1648–2016 (2017).

- Michaelis, Meir. «World Power Status or World Dominion? A Survey of the Literature on Hitler’s ‘Plan of World Dominion’ (1937–1970).» Historical Journal 15#2 (1972): 331–60. online.

- Ogden, Chris. China and India: Asia’s emergent great powers (John Wiley & Sons, 2017).

- Newmann, I.B. ed. Regional Great Powers in International Politics (1992)

- Schulz, Matthias. «A Balancing Act: Domestic Pressures and International Systemic Constraints in the Foreign Policies of the Great Powers, 1848–1851.» German History 21.3 (2003): 319–346.

- Mearsheimer, John J. (2001). The Tragedy of Great Power Politics. New York: Norton. ISBN 0393020258.

- Neumann, Iver B.»Russia as a great power, 1815–2007.» Journal of International Relations and Development 11.2 (2008): 128–151. online

- O’Brian, Patrick K. Atlas of World History (2007) Online

- Peden, G. C. «Suez and Britain’s Decline as a World Power.» Historical Journal55#4 (2012), pp. 1073–1096. online

- Pella, John & Erik Ringmar, (2019) History of international relations Online Archived 16 August 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Shifrinson, Joshua R. Itzkowitz. Rising titans, falling giants: how great powers exploit power shifts (Cornell UP, 2018).

- Waltz, Kenneth N. (1979). Theory of International Politics. Reading: Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0201083493.

- Ward, Steven. Status and the Challenge of Rising Powers (2018) excerpt from book; also online review

- Witkopf, Eugene R. (1981). World Politics: Trend and Transformation. New York: St. Martin’s Press. ISBN 0312892462.

- Xuetong, Yan. Leadership and the rise of great powers (Princeton UP, 2019).

External links[edit]

- Rising Powers Project publishes Rising Powers Quarterly (2016- )

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale.[2] Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power influence, which may cause middle or small powers to consider the great powers’ opinions before taking actions of their own. International relations theorists have posited that great power status can be characterized into power capabilities, spatial aspects, and status dimensions.[3]

While some nations are widely considered to be great powers, there is considerable debate on the exact criteria of great power status. Historically, the status of great powers has been formally recognized in organizations such as the Congress of Vienna[1][4][5] or the United Nations Security Council.[1][6][7] The United Nations Security Council, NATO Quint, the G7, the BRICs and the Contact Group have all been described as great power concerts.[8][9]

The term «great power» was first used to represent the most important powers in Europe during the post-Napoleonic era. The «Great Powers» constituted the «Concert of Europe» and claimed the right to joint enforcement of the postwar treaties.[10] The formalization of the division between small powers[11] and great powers came about with the signing of the Treaty of Chaumont in 1814. Since then, the international balance of power has shifted numerous times, most dramatically during World War I and World War II. In literature, alternative terms for great power are often world power[12] or major power.[13]

Characteristics[edit]

There are no set or defined characteristics of a great power. These characteristics have often been treated as empirical, self-evident to the assessor.[14] However, this approach has the disadvantage of subjectivity. As a result, there have been attempts to derive some common criteria and to treat these as essential elements of great power status. Danilovic (2002) highlights three central characteristics, which she terms as «power, spatial, and status dimensions,» that distinguish major powers from other states. The following section («Characteristics») is extracted from her discussion of these three dimensions, including all of the citations.[15]

Early writings on the subject tended to judge states by the realist criterion, as expressed by the historian A. J. P. Taylor when he noted that «The test of a great power is the test of strength for war.»[16] Later writers have expanded this test, attempting to define power in terms of overall military, economic, and political capacity.[17] Kenneth Waltz, the founder of the neorealist theory of international relations, uses a set of five criteria to determine great power: population and territory; resource endowment; economic capability; political stability and competence; and military strength.[18] These expanded criteria can be divided into three heads: power capabilities, spatial aspects, and status.[19]

John Mearsheimer defines great powers as those that «have sufficient military assets to put up a serious fight in an all-out conventional war against the most powerful state in the world.»[20]

Power dimensions[edit]

German historian Leopold von Ranke in the mid-19th century attempted to scientifically document the great powers.

As noted above, for many, power capabilities were the sole criterion. However, even under the more expansive tests, power retains a vital place.

This aspect has received mixed treatment, with some confusion as to the degree of power required. Writers have approached the concept of great power with differing conceptualizations of the world situation, from multi-polarity to overwhelming hegemony. In his essay, ‘French Diplomacy in the Postwar Period’, the French historian Jean-Baptiste Duroselle spoke of the concept of multi-polarity: «A Great power is one which is capable of preserving its own independence against any other single power.»[21]

This differed from earlier writers, notably from Leopold von Ranke, who clearly had a different idea of the world situation. In his essay ‘The Great Powers’, written in 1833, von Ranke wrote: «If one could establish as a definition of a Great power that it must be able to maintain itself against all others, even when they are united, then Frederick has raised Prussia to that position.»[22] These positions have been the subject of criticism.[clarification needed][19]

In 2011 the U.S. had 10 major strengths according to Chinese scholar Peng Yuan, the director of the Institute of American Studies of the China Institutes for Contemporary International Studies.[23]

- 1. Population, geographic position, and natural resources.

- 2. Military muscle.

- 3. High technology and education.

- 4. Cultural/soft power.

- 5. Cyber power.

- 6. Allies, the United States having more than any other state.

- 7. Geopolitical strength, as embodied in global projection forces.

- 8. Intelligence capabilities, as demonstrated by the killing of Osama bin Laden.

- 9. Intellectual power, fed by a plethora of U.S. think tanks and the “revolving door” between research institutions and government.

- 10. Strategic power, the United States being the world’s only country with a truly global strategy.

However he also noted where the U.S. had recently slipped:

- 1. Political power, as manifested by the breakdown of bipartisanship.

- 2. Economic power, as illustrated by the post-2007 slowdown.

- 3. Financial power, given intractable deficits and rising debt.

- 4. Social power, as weakened by societal polarization.

- 5. Institutional power, since the United States can no longer dominate global institutions

Spatial dimension[edit]

All states have a geographic scope of interests, actions, or projected power. This is a crucial factor in distinguishing a great power from a regional power; by definition, the scope of a regional power is restricted to its region. It has been suggested that a great power should be possessed of actual influence throughout the scope of the prevailing international system. Arnold J. Toynbee, for example, observes that «Great power may be defined as a political force exerting an effect co-extensive with the widest range of the society in which it operates. The Great powers of 1914 were ‘world-powers’ because Western society had recently become ‘world-wide’.»[24]

Other suggestions have been made that a great power should have the capacity to engage in extra-regional affairs and that a great power ought to be possessed of extra-regional interests, two propositions which are often closely connected.[25]

Status dimension[edit]

Formal or informal acknowledgment of a nation’s great power status has also been a criterion for being a great power. As political scientist George Modelski notes, «The status of Great power is sometimes confused with the condition of being powerful. The office, as it is known, did in fact evolve from the role played by the great military states in earlier periods… But the Great power system institutionalizes the position of the powerful state in a web of rights and obligations.»[26]

This approach restricts analysis to the epoch following the Congress of Vienna at which great powers were first formally recognized.[19] In the absence of such a formal act of recognition it has been suggested that great power status can arise by implication by judging the nature of a state’s relations with other great powers.[27]

A further option is to examine a state’s willingness to act as a great power.[27] As a nation will seldom declare that it is acting as such, this usually entails a retrospective examination of state conduct. As a result, this is of limited use in establishing the nature of contemporary powers, at least not without the exercise of subjective observation.

Other important criteria throughout history are that great powers should have enough influence to be included in discussions of contemporary political and diplomatic questions, and exercise influence on the outcome and resolution. Historically, when major political questions were addressed, several great powers met to discuss them. Before the era of groups like the United Nations, participants of such meetings were not officially named but rather were decided based on their great power status. These were conferences that settled important questions based on major historical events.

History[edit]