А Б В Г Д Е Ж З И Й К Л М Н О П Р С Т У Ф Х Ц Ч Ш Щ Э Ю Я

вьетна́мский, (от Вьетна́м)

Рядом по алфавиту:

выясне́ние , -я

вы́ясненный , кр. ф. -ен, -ена

выя́сниваться , -ается (о погоде)

вы́яснить(ся) , -ню, -нит(ся)

выясня́ть(ся) , -я́ю, -я́ет(ся)

вьентья́нский , (от Вьентья́н)

вьентья́нцы , -ев, ед. -нец, -нца, тв. -нцем

вьетко́нговский , (от Вьетко́нг)

вьетко́нговцы , -ев, ед. -вец, -вца, тв. -вцем

вьетна́мка , -и, р. мн. -мок

вьетна́мки , -мок, ед. -мка, -и (обувь)

вьетна́мо-америка́нский

вьетна́мо-кита́йский

вьетна́мо-росси́йский

вьетна́мо-францу́зский

вьетна́мский , (от Вьетна́м)

вьетна́мско-ру́сский

вьетна́мцы , -ев, ед. -мец, -мца, тв. -мцем

вью́га , -и

вьюгове́й , -я

вью́ер , -а

вью́ерный

вью́жистый

вью́жить(ся) , -ит(ся)

вью́жливый

вью́жно , нареч. и в знач. сказ.

вью́жный , кр. ф. -жен, -жна

вьюк , -а и вьюка́

вьюковожа́тый , -ого

вьюн , вьюна́

вьюни́ть , -ни́т

|

Общие фразы |

||

|

цо, ванг, да |

||

|

Пожалуйста |

хонг цо чи |

|

|

Извините |

||

|

Здравствуйте |

||

|

До свидания |

||

|

Я не понял |

||

|

Как вас зовут? |

ten anh (chi) la gi? |

тен анх ла ги |

|

нья ве син |

||

|

Сколько это стоит? |

cai nay gia bao nhieu? |

цай най гиа бао нхиэу? |

|

Который час? |

may gio ro`i nhi? |

мау гио ро»и нхи? |

|

Вы говорите по-английски |

co noi tieng khong? |

цо ной тиенг хонг анх? |

|

Как это сказать? |

cai nay tieng noi the? |

цай най тиенг ной тэ? |

|

Я из России |

tôi đến từ Nga |

тои ден ту Нга |

|

Гостиница |

||

|

Магазин (покупки) |

||

|

Наличные |

||

|

Кредитная карточка |

thẻ tín dụng thẻ |

тэ тин дунг тэ |

|

Упаковать |

||

|

Без сдачи |

mà không cần dùng |

ма хонг сан дунг |

|

Очень дорого |

||

|

Транспорт |

||

|

Мотоцикл |

хэ ган май |

|

|

Аэропорт |

||

|

га хе луа |

||

|

Отправление |

ди, хо ханх |

|

|

Прибытие |

||

|

Экстренные случаи |

||

|

Пожарная служба |

sở cứu hỏa |

со суу хоа |

|

до»н цанх сат |

||

|

Скорая помощь |

xe cứu thương |

хэ суу хуонг |

|

Больница |

бенх виен |

|

|

хиеу туоц |

||

|

Ресторан |

||

|

нуоц трай цау |

||

|

Мороженое |

Язык Вьетнама

Какой язык во Вьетнаме

Официальный язык во Вьетнаме

— вьетнамский (тьенг вьет).

Вьетнамский язык широко распространен также в Камбодже, Лаосе, Таиланде, Малайзии, Австралии, Франции, Германии, США, Канаде. Во всем мире на нем говорят более 80 миллионов человек.

Язык Вьетнама

имеет особенности в разных регионах страны. Выделяется три основных диалекта: северных, центральный и южный.

Так как Ханой является городом с развитой туристической инфраструктурой, в отелях, ресторанах и кафе персонал владеет разговорным английским языком. В сфере обслуживания также в ходу французский и русские языки. Сложности перевода

русских путешественников в развитых туристических центрах Вьетнама обходят стороной.

Язык Вьетнама

имеет сложный фонологический строй. Одно слово, произнесенное разной интонацией и тоном, может иметь до шести значений.

Долгое время язык Вьетнама

находился под влиянием китайского языка. Две трети слов языка вьетов происходят от китайского языка, а в период французского владычества вьетнамская лексика обогатилась французскими словами.

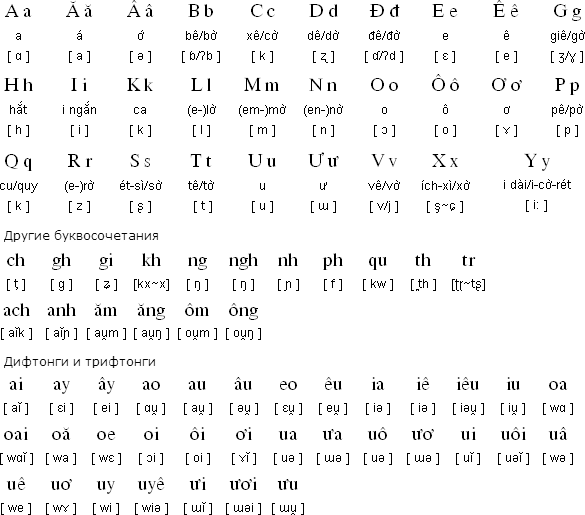

До начала 20 века алфавит Вьетнама

был иероглифическим. Но чуть более столетие назад в стране было введено письмо на латинице. К латинским гласным буквам были добавлены диакритические знаки, обозначающие тон произношения буквы. Современный вьетнамский алфавит состоит из 29 букв.

Вьетнамский язык очень сложный, так как гласные буквы в нем имеют разные тональности, именно поэтому русско-вьетнамский разговорник для туристов включает в себя минимум слов. Русско-вьетнамский разговорник пригодится вам на местных рынках и в ресторанах, но имейте в виду, что человек, незнакомый с правилами вьетнамского произношения, будет говорить с сильным акцентом и может быть не понят. В туристический зонах к этому привыкли и обычно понимают простые фразы, сказанные иностранцами, стоит же вам уехать в отдаленные от курортов места, вам будет намного сложнее изъясняться, даже используя русско-вьетнамский разговорник.

Русско-вьетнамский разговорник: зачем он нужен

Используйте наш коротенький русско-вьетнамский разговорник, ведь если вьетнамцам удастся вас понять, они будут очень рады этому, отнесутся к к вам с большой теплотой и дадут вам скидки больше, чем дают обычно.

Русско-вьетнамский разговорник: приветствие и прощание

Вьетнамцы, здороваясь между собой, обычно акцентируют внимание на том, к кому они обращаются. В зависимости от возраста и пола, приветствие может звучать по-разному. Но, чтобы не путаться в обращениях, наш русско-вьетнамский разговорник предлагает вам единое общее приветствие, которое подойдет для всех: Xin chào

(Синь чао). Приходя в любое кафе или лавочку скажите «Син чао», это очень порадует вьетнамцев.

Попрощаться можно, используя слово Tạm biệt

(Там бьет). Это выражение подходит для мест, в которые вы можете не вернуться (означает скорее «прощайте»). Если вам хочется быть еще вежливее и обозначить возможность новой встречи, можно сказать Hẹn gặp lại

(Хэн гап лай), которую можно перевести на русский язык как «увидимся, до встречи».

Какое слово самое полезное в любой стране после приветствия? Ну конечно же, это слово «спасибо». По-вьетнамски оно звучит как Cảm ơn

(Кам он). Запомнить его очень легко, так как многим знакомо английское выражение, звучащее схожим образом, но означающее совершенно иное =)

Если в ответ на ваше спасибо, вы услышите слова Không có gì

(Хон ко чи), это означает «не за что».

Русско-вьетнамский разговорник: в ресторане

В ресторане вам пригодится следующий мини русско-вьетнамский разговорник.

Для того, чтобы узнать какое из блюдо лучше заказать, задайте официанту вопрос Món gì ngon?

(Мон зи нён). Это фраза будет примерно равнозначна русскому вопросу — «Какое из блюд хорошее?».

Кушая во вьетнамском кафе, вам обязательно захочется поблагодарить повара и выразить свои мысли по-поводы еды. Вьетнамские кушанья могут быть абсолютно простыми, такими как рис с курицей или суп с лапшой, а могут быть экзотическими и замысловатыми, например, суп из ласточкиных гнезд или барбекю из крокодила. В любой случае эта еда будет очень вкусной! Сказать об этом можно, используя простую фразу Ngon quá!

(Нон ква), которая означает в переводе «очень вкусно».

Чтобы попросить счет, скажите: Tính tiền

(Тинь тьен), официант должен понять вас и рассчитать.

Русско-вьетнамский разговорник: на рынке

Для того, чтобы легче было ориентироваться на рынке, нужно знать цифры:

- один — một

(мот) - два — hai

(хай) - три — ba

(ба) - четыре — bốn

(бон) - пять — năm

(нам) - шесть — sáu

(сау) - семь — bảy

(бай) - восемь — tám

(там) - девять — chín

(чинь) - десять — mười

(муй)

Для того, чтобы торговаться, достаточно будет одного элементарного đắt quá

(Дат ква) — очень дорого. Для удобства вы можете назначать свою цену, пользуясь калькулятором, он должен быть у каждого продавца.

Остается добавить, что если вы не знаете ни слова по вьетнамски — это тоже не страшно. На территории большинства курортов вьетнамцы говорят на английском или даже русском языках (в Муйне на русском говорит большинство продавцов, менеджеров и администраторов), поэтому у вас вряд ли возникнут трудности при общении.

Произношение вьетнамских слов и фраз в данном мини-разговорнике дается приближенно. Активно использовать эти слова и фразы не рекомендуется, так как при неправильной интонации смысл сказанного может быть сильно искажен. Это связано с тем, что вьетнамский язык является тоновым и казалось бы одно и то же слово, но, сказанное по разному, означает совсем разные вещи и понятия.

Звук «г» в конце слова произносится нечетко. Если написано два звука «а», то это значит просто удлиненное «а». Звук «х» после «т» произносится слабо.

В верхней части изображения надпись большими буквами на вьетнамском языке означает «Рынок Донг Суан» (Cho -рынок). В нижней части — «Вокзал Ханоя». Слово «ga» (вокзал) произошло от французского «gare».

Аэропорт, прибытие, контроль

Самолет — май бай

Паспорт — хо чьеу

Таможня — хай куаан

Иммиграционный контроль — ньяп каньг

Виза — тхии тук.

Стирка — жатдо (GIẶT ĐỒ)

В отеле

Отель — кхаак шан

Я бы хотел забронировать — лаам эн чо дой дат чыок моот

Можно посмотреть? — гой до те сэм фом дыок кхон?

С… до … (имеются в виду проживание с такого-то числа до такого-то) — ду … дэн …

Номер — со

Сколько стоит номер? Зья мот фом лаа боу ньеу?

Дата — нгай таанг

Мы съезжаем завтра — нгай май чунг дой зери дай

Кредитная карта — тхэ дин зун

Кондиционер — май лань

В ресторане

Ресторан — нья хан[г]

Я бы хотел — син чо дой

Говядина — тхьит бо

свинина — тхьит хейо

Курица — тхьит га

Рыба — каа

Орешки — дау фонг

Ложка — кай тхиа

Нож — гон зао

Вилка — кай ньиа

Числа

Туристам часто приходится иметь дело с числами.

Один — мот

Два — хай

Три — ба

Четыре — бон

Пять — нам

Шесть — шау

Семь — бай

Восемь — там

Девять — тин

Десять — мыой

Далее просто: 11 — десять и один=мыой мот, двенадцать=мыой хай и т.д. Только 15 будет не мыой нам, а мыой лам.

Двадцать — хай мыой (то есть, два десять) , 21 — хай мыой мот (два десять один).

Сто — мот чам, то есть одна сотня. 101 — мот чам лин мот, то есть, сто, затем что-то вроде нуля, затем один. 123 — мот чам хай мыой ба (одна сотня,

два десятка, три).

Тысяча — нгин, миллион — чиеу.

Процент — фан чам. 100% — мот чам фан чам.

Местоимения

Я — той, мой — ку:а той

Ты — кау ань или кау ти, в зависимости от того, к мужчине или женщине

обращаются (ань — мужчина, ти — женщина) твой — ку:а кау, а

также куа:ань, куа:ти

Вы — ань, ваш — ку:а ань

Он — ань_эй, ом_эй, ку:а

Она, её — ти_эй, ба_эй, ку:а, ти_эй,

ку:а ба_эй

Мы, наш — тюн[г]_та, тюн[г]_той,

ку:а тюн[г]_та, ку:а тюн[г]_той

Вы, ваш — как_ань (как_ти, как ом, как ба), ку:а как_ань (ку:а как_ти,

ку:а как ом, ку:а как ба)

Они, их — хо ку:а хо

Кто, чей — ай, ку:а ай

Что — зи, кай зи

Этот, та, это, эти — наи

Тот, та, то, те — кия

Приветствие

Здравствуйте — синь тяо (звук «т» произносится как среднее между «ч» и «т»). Это приветствие наиболее универсально и наиболее употребительно.

Его разновидности:

При обращении к мужчине до 40-45 лет — Тяо ань!

при обращении к женщине до 40-45 лет — Тяо ти!

при обращении к пожилому мужчине/пожилой женщине — Тяо ом!/Тяо ба!

… господин/госпожа — Тяо ом!/Тяо ба!

… друг — Тяо бан!

… при обращении к младшему по возрасту — Тяо эм!

… при обращении к ребенку — Тяо тяу!

При обращении к группе людей добавляется слово как

, обозначающее множественное число.

… при обращении к мужчинам — Тяо как_ань/как_ом! (в зависимости от возраста)

… при обращении к женщинам — Тяо как_ти/как_ба! (в зависимости от возраста)

… при обращении к мужчинам и женщинам, если присутствуют представители обоих

полов — Тяо как_ань, как_ти (как_ом, как_ба)!

… друзья (господа, господин и госпожа, товарищи) — Тяо как_бан (как_ом, ом_ба, как_дом_ти)!

До свидания — Там _биет ань! (вместо ань говорится ти, ом, ба и т.д., в зависимости от того, с кем прощаетесь). Но, так говорится в торжественных случаях. Более употребительным является просто «Тяо».

В городе

Скажите, пожалуйста — Лам_ын тё_бет…

Какой здесь адрес? Дьеа чии лаа зи?

Где находится банк — нган_хан[г] о:дау?

Ключевым здесь является слово где — о:дау?

Например: «Где вокзал?» — ня_га о:дау?

и так далее …

Магазин — кыа_хан[г]

Остановка автобуса — чам сэ_буит

Парикмахерская — хиеу кат_таук

Туалет — нья ве син

Стоянка такси — бэн так_си

Помогите мне, пожалуйста — лам_ын (пожалуйста) зуп (помогите) той (я, мне)

Напишите мне, пожалуйста — лам_ын (пожалуйста) виет хо (напишите) той (я, мне)

Повторите, пожалуйста, еще раз — син няк_лай мот лан ныа

Объясните, мне, пожалуйста — лам_ын зай_тхыть тё той

Разрешите спросить — тё_фэп той хой

Как это называется по-вьетнамски? — кай_наи тыен[г] вьет гой тхэ_нао?

Сто грамм — мот_чам (сто) гам (грамм)

Спасибо — кам_ын.

Большое спасибо — жэт кам_ын ань (вместо ань говорится ти, ом, ба и т.д., в зависимости от того, кого благодарите).

Общение

Извините — син_лой

Không can. Произносится как «(к)хом кан» — не надо, не нуждаюсь (категоричная форма).

Покупки, шоппинг — муа бан

Я (той) хочу (муон) примерить (мак_тхы)…

платье (ао_вай) это (най)

куан (брюки) най (эти)

юбку (вай) най (эту)

Сколько стоит? — Зао бао ньеу?

Очень дорого — дат куа

Нельзя ли дешевле? — ко жэ хын кхом?

Электронные разговорники

С развитием компактных электронных устройств в них начали «вшивать» программы голосового электронного перевода, кратко называемые электронными разговорниками. Этот же термин применяется и к самим устройствам, единственной функцией которых является устный электронный перевод.

Электронный перевод осуществляется и другими устройствами, например, смартфонами или планшетными компьютерами, если в них предусмотрена соотвествующая аппаратная и программная функциональность.

Электронные разговорники могут использоваться и в качестве мини-самоучителей иностранного языка.

Некоторые модели электронных разговорников содержат программы и словарные базы по переводу нескольких десятков языков в различных направлениях. Они особенно привлекательны для тех, кто много и часто путешествует по разным странам. Их стоимость находится в пределах $150-200.

На каком языке говорят во Вьетнаме, интересуются все туристы, которые стремятся оказаться в этой стране. А в последнее время количество людей, которые отправляются в это юго-восточное государство, только увеличивается. Вьетнам привлекает экзотической природой, недорогим отдыхом и радушием местных жителей, с которыми хочется перекинуться хотя бы парой слов на их родном языке.

Официальный язык

Вьетнам — многонациональная страна. В ней существуют как официальный, так и непризнанные языки. Но все же, выясняя, на каком языке говорят во Вьетнаме, стоит признать, что большинство отдает предпочтение вьетнамскому. Он является государственным, при этом часть населения свободно общается на французском, английском и китайском языках.

Государственный язык Вьетнама служит для образования и межнационального общения. Помимо самого Вьетнама, он также распространен в Лаосе, Камбодже, Австралии, Малайзии, Таиланде, Германии, Франции, США, Германии, Канаде и других странах. Всего на нем говорят около 75 миллионов человек, из которых 72 млн проживают во Вьетнаме.

На этом языке во Вьетнаме разговаривают 86 процентов населения. Интересно, что до самого конца XIX века он преимущественно использовался только для бытового общения и написания художественных произведений.

История Вьетнама

Рассказывая, на каком языке говорят во Вьетнаме, нужно отметить, что на это наложила отпечаток история государства. Во II веке до нашей эры территория современной страны, которой посвящена эта статья, была завоевана Китаем. Фактически вьетнамцы оставались под протекторатом китайцев вплоть до X века. Именно по этой причине китайский язык служил основным для официального и письменного общения.

К тому же вьетнамские правители уделяли пристальное внимание конкурсным экзаменам при назначении нового чиновника на ту или иную должность. Это требовалось для отбора наиболее квалифицированных сотрудников, экзамены на протяжении нескольких веков проводились исключительно на китайском языке.

Как появился вьетнамский язык

Вьетнама в качестве самостоятельного литературного начал возникать только в конце XVII столетия. В то время французский монах-иезуит по имени Александр де Род разработал вьетнамский алфавит на основе латинского. В нем тоны обозначались особенными диакритическими значками.

Во второй половине XIX века колониальная администрация Франции, чтобы ослабить традиционное влияние китайского языка на Вьетнам, способствовала его развитию.

Современный литературный вьетнамский язык опирается на северный диалект ханойского говора. При этом письменная форма литературного языка основывается на звуковом составе центрального диалекта. Интересная особенность состоит в том, что на письме каждый слог отделяется пробелом.

Теперь вы знаете, какой язык во Вьетнаме. В наше время на нем говорит абсолютное большинство жителей этого государства. При этом, по оценкам специалистов, всего в стране около 130 языков, которые в большей или меньшей степени распространены на территории этой страны. Вьетнамский язык используется как средство общения на самом высоком уровне, а также среди простых людей. Это официальный язык в бизнесе и образовании.

Особенности вьетнамского языка

Зная, на каком языке говорят во Вьетнаме, стоит разобраться в его особенностях. Он относится к австроазиатской семье, вьетской группе. Скорее всего, по своему происхождению он близок к мыонгскому языку, однако изначально причислялся к группе тайских наречий.

У него большое количество диалектов, из которых выделяют три основных, каждый из которых делится на свои наречия и говоры. Северный диалект распространен в центре страны, в Хошимине и окружающих его районах популярен южный диалект. Все они различаются лексикой и фонетикой.

Грамматика

Всего во вьетнамском языке около двух с половиной тысяч слогов. Интересно, что их количество может меняться в зависимости от принадлежности к тому или иному диалекту. Это изолирующий язык, который в одно и то же время является тональным и слоговым.

Практически во всех языках этой группы сложные слова упрощаются до односложных, часто это касается и исторических слов, хотя в последнее время началась обратная тенденция. Во вьетнамском языке отсутствуют словоизменения и аналитические формы. То есть все грамматические отношения строятся исключительно на основе служебных слов, а приставки, суффиксы и аффиксы не играют в этом никакой роли. Знаменательные части речи включают в себя глаголы, прилагательные и предикативы. Еще одна отличительная особенность — это использование родственных терминов вместо личных местоимений.

Словообразование

Большинство слов в литературном вьетнамском языке образуются при помощи аффиксов, в основном имеющих китайское происхождение, а также сложения корней, удвоения слов или слогов.

Одна из ключевых особенностей словообразования заключается в том, что все компоненты, участвующие в образовании слов, являются односложными. Удивительно, но один слог может иметь сразу несколько значений, которые могут меняться от интонации при их произношении.

В предложении фиксированный порядок слов: сначала идет подлежащее, а затем сказуемое и дополнение. Большинство вьетнамских слов заимствованы из китайского языка, причем из разных исторических периодов, также много австроазиатской лексики.

Имена людей во Вьетнаме слагаются из трех слов — это фамилия матери или отца, прозвище и имя. По фамилии вьетов не называют, как в России, чаще всего их идентифицируют по имени. Еще одна особенность вьетнамских имен в прежние времена заключалась в том, что среднее имя явно указывало на пол ребенка при рождении. Причем если имя девочки состояло из одного слова, то у мальчика это могли быть несколько десятков слов. В наше время такая традиция исчезла.

Популярность вьетнамского языка

Из-за того, что в наше время на этом языке говорят во многих азиатских и европейских странах, неудивительно, что его популярность растет с каждым годом. Многие его учат для того, чтобы открыть бизнес в этом стремительно развивающемся государстве.

Определенные товары из Вьетнама сейчас не уступают ни в качестве, ни в стоимости, а культура и традиции настолько интересны и удивительны, что многие стремятся к ним приобщиться.

В самом Вьетнаме в сфере туризма активно используют английский, французский и китайский языки, достаточно много можно встретить русскоговорящий персонал, особенно среди тех, кто в советское время получал образование в СССР. Те, кто осваивает этот язык, отмечают, что он очень похож на китайский. В обоих языках слоги несут особую смысловую нагрузку, а интонации играют едва ли не решающую роль.

В России это достаточно редкий язык, существует всего несколько школ, которые помогут его освоить. Если вы все же решились его изучать, то будьте готовы к тому, что занятия могут начаться только после набора группы, возможно, ждать придется достаточно долго, поэтому лучше изначально ориентироваться на встречи с индивидуальным преподавателем.

Распространенные фразы на вьетнамском

Так что не так просто изучить этот язык. Общение в Вьетнаме при этом часто хочется построить на родном наречии, чтобы расположить к себе местных жителей. Не составляет большого труда освоить несколько популярных фраз, которые продемонстрируют в разговоре, насколько вы проникаете в местную культуру:

- Здравствуйте — син тяо.

- Дорогие друзья — как бан тхан мэйн.

- До свидания — хен гап лай нья.

- Где мы встретимся — тюнг та гап няу о дау?

- Пока — дди нхэ.

- Да — цо, ванг, да.

- Нет — хонг.

- Спасибо — кам он.

- Пожалуйста — хонг цо чи.

- Извините — хин лой.

- Как вас зовут — ань тэйн ла ди?

- Меня зовут… — той тэйн ла…

Надеемся, вы узнали много интересного о языке и культуре Вьетнама. Желаем интересных путешествий в эту страну!

Вьетнамский язык

(tiếng việt / 㗂越) – это один из австроазиатских языков, который насчитывает около 82 миллионов носителей, преимущественно, во Вьетнаме. Кроме того, носители вьетнамского языка встречаются в США, Китае, Камбодже, Франции, Австралии, Лаосе, Канаде и ряде других стран. Вьетнамский язык является государственным языком Вьетнама с 1954 г., когда это государство получило независимость от Франции.

История

Далекий предок современного вьетнамского языка появился на свет в дельте Красной реки в северной части Вьетнама. Первоначально он находился под сильным влиянием индийских и малайско-полинезийских языков, но все изменилось после того, как китайцы стали управлять прибрежным народом со II в. до н.э.

На протяжении тысячелетия около 30 династий китайских правителей господствовали во Вьетнаме. В течение этого периода был языком литературы, образования, науки, политики, а также использовался вьетнамской аристократией. Простые люди, тем не менее, продолжали говорить на местном языке, для письма на котором использовали символы тьи-ном (chữ nôm jũhr nawm). Эта система письма состояла из китайских иероглифов, адаптированных под вьетнамские звуки, и использовалась до начала ХХ в. Более двух третей вьетнамских слов произошли из китайских источников – такая лексика называется сино-вьетнамской (Hán Việt haán vee·ụht).

После столетия борьбы за независимость вьетнамцы начали управлять своей землей в 939 г. Вьетнамский язык, использующий на письме символы тьи-ном (chữ nôm), завоевывал авторитет по мере того, как возрождался народ. Это был самый плодотворный период в развитии вьетнамской литературы, во время которого появились такие великие произведения, как поэзия Хо Суан Хыонг и «Поэма о Кьеу» (Truyện Kiều chwee·ụhn ğee·oò) Нгуена Зу.

Первые европейские миссионеры пришли во Вьетнам в XVI в. Французы постепенно утвердились в качестве доминирующей европейской силы в этом регионе, вытеснив португальцев, и присоединили Вьетнам к Индокитаю в 1859 г. после того, как установили свой контроль над Сайгоном.

Французская лексика начала использоваться во Вьетнаме, и в 1610 г. на основе латинского алфавита была создана новая официальная система письма вьетнамского языка, куокнгы (quốc ngữ gwáwk ngũhr script), которая еще больше усилила французское правление. Этот 29-буквенный фонетический алфавит разработал в XVII в. французский монах-иезуит Александр де Род. В настоящее время почти всегда на письме используется куокнгы (quốc ngữ).

Несмотря на многие конфликтные ситуации, с которыми Вьетнаму пришлось столкнуться с середины прошлого века, во вьетнамском языке мало что изменилось. Некоторые изменения в куокнгы (quốc ngữ) все же произошли в 1950-60-х гг., благодаря чему во вьетнамском письме нашел свое отображение средневьетнамский диалект, которые объединяет в себе начальные согласные, характерные для юга, с гласными и финальными согласными, характерными для севера.

В настоящее время вьетнамский язык является официальным языком Социалистической Республики Вьетнам. На этом языке говорит около 85 миллионов человек по всему миру, во Вьетнаме и эмигрантских общинах в Австралии, Европе, Северной Америке и Японии.

Письменность

Первоначально для письма на вьетнамском языке использовали письмо на основе китайской иероглифики под названием тьы-ном (Chữ-nôm (喃) или Nôm (喃)). Поначалу большая часть вьетнамской литературы сохраняла структуру и лексический состав китайского языка. В более поздней литературе начал развиваться вьетнамский стиль, но всё равно в произведениях оставалось много слов, заимствованных из китайского языка. Самым известным литературным произведением на вьетнамском языке является «Поэма о Кьеу», написанная Нгуен Зу (1765-1820).

Письмо тьы-ном использовалось до ХХ в. Обучающие курсы тьы-ном были доступны в Университете Хо Ши Мин до 1993 г., и до сих пор это письмо изучают и преподают в Институте Хан Ном в Ханое, где недавно был опубликован словарь всех иероглифов тьы-ном.

В ХVII в. римские католические миссионеры представили систему письма на вьетнамском языке на латинской основе, куокнгы (Quốc Ngữ) (государственный язык), которая с тех пор и используется. До начала ХХ в. система письма куокнгы использовалась параллельно с тьы-ном. В наше время используется только куокнгы.

Вьетнамский алфавит и фонетическая транскрипция

Примечания

- Буквы «F», «J», «W» и «Z» не являются частью вьетнамского алфавита, но используются в иностранных заимствованных словах. «W» (vê-đúp)» иногда используется вместо «Ư» в сокращениях. В неофициальной переписке «W», «F», и «J» иногда используются как сокращения для «QU», «PH» и «GI» соответственно.

- Диграф «GH» и триграф «NGH», в основном, заменяют «G» и «NG» перед «I», чтобы не перепутать с диграфом «GI». По историческим причинам, они также используются перед «E» или «Ê».

- G = [ʒ] перед i, ê, и e, [ɣ] в другой позиции

- D и GI = [z] в северных диалектах (включая ханойский диалект), и [j] в центральных, южных и сайгонских диалектах.

- V произносится как [v] в северных диалектах, и [j] в южных диалектах.

- R = [ʐ, ɹ] в южных диалектах

Вьетнамский язык относится к тоновым языкам и насчитывает 6 тонов, которые обозначаются следующим образом:

1. ровный = призрак

2. высокий восходящий = щека

3. нисходящий = но

4. восходяще-нисходящий = могила

5. нисходяще-восходящий = лошадь

6. резко нисходящий = рисовый побег

Вьетнамский язык (tiếng việt / 㗂越) – это один из австроазиатских языков, который насчитывает около 82 миллионов носителей, преимущественно, во Вьетнаме. Кроме того, носители вьетнамского языка встречаются в США, Китае, Камбодже, Франции, Австралии, Лаосе, Канаде и ряде других стран. Вьетнамский язык является государственным языком Вьетнама с 1954 г., когда это государство получило независимость от Франции.

История

Далекий предок современного вьетнамского языка появился на свет в дельте Красной реки в северной части Вьетнама. Первоначально он находился под сильным влиянием индийских и малайско-полинезийских языков, но все изменилось после того, как китайцы стали управлять прибрежным народом со II в. до н.э.

На протяжении тысячелетия около 30 династий китайских правителей господствовали во Вьетнаме. В течение этого периода китайский язык был языком литературы, образования, науки, политики, а также использовался вьетнамской аристократией. Простые люди, тем не менее, продолжали говорить на местном языке, для письма на котором использовали символы тьи-ном (chữ nôm jũhr nawm). Эта система письма состояла из китайских иероглифов, адаптированных под вьетнамские звуки, и использовалась до начала ХХ в. Более двух третей вьетнамских слов произошли из китайских источников – такая лексика называется сино-вьетнамской (Hán Việt haán vee·ụht).

После столетия борьбы за независимость вьетнамцы начали управлять своей землей в 939 г. Вьетнамский язык, использующий на письме символы тьи-ном (chữ nôm), завоевывал авторитет по мере того, как возрождался народ. Это был самый плодотворный период в развитии вьетнамской литературы, во время которого появились такие великие произведения, как поэзия Хо Суан Хыонг и «Поэма о Кьеу» (Truyện Kiều chwee·ụhn ğee·oò) Нгуена Зу.

Первые европейские миссионеры пришли во Вьетнам в XVI в. Французы постепенно утвердились в качестве доминирующей европейской силы в этом регионе, вытеснив португальцев, и присоединили Вьетнам к Индокитаю в 1859 г. после того, как установили свой контроль над Сайгоном.

Французская лексика начала использоваться во Вьетнаме, и в 1610 г. на основе латинского алфавита была создана новая официальная система письма вьетнамского языка, куокнгы (quốc ngữ gwáwk ngũhr script), которая еще больше усилила французское правление. Этот 29-буквенный фонетический алфавит разработал в XVII в. французский монах-иезуит Александр де Род. В настоящее время почти всегда на письме используется куокнгы (quốc ngữ).

Несмотря на многие конфликтные ситуации, с которыми Вьетнаму пришлось столкнуться с середины прошлого века, во вьетнамском языке мало что изменилось. Некоторые изменения в куокнгы (quốc ngữ) все же произошли в 1950-60-х гг., благодаря чему во вьетнамском письме нашел свое отображение средневьетнамский диалект, которые объединяет в себе начальные согласные, характерные для юга, с гласными и финальными согласными, характерными для севера.

В настоящее время вьетнамский язык является официальным языком Социалистической Республики Вьетнам. На этом языке говорит около 85 миллионов человек по всему миру, во Вьетнаме и эмигрантских общинах в Австралии, Европе, Северной Америке и Японии.

Письменность

Первоначально для письма на вьетнамском языке использовали письмо на основе китайской иероглифики под названием тьы-ном (Chữ-nôm (喃) или Nôm (喃)). Поначалу большая часть вьетнамской литературы сохраняла структуру и лексический состав китайского языка. В более поздней литературе начал развиваться вьетнамский стиль, но всё равно в произведениях оставалось много слов, заимствованных из китайского языка. Самым известным литературным произведением на вьетнамском языке является «Поэма о Кьеу», написанная Нгуен Зу (1765-1820).

Письмо тьы-ном использовалось до ХХ в. Обучающие курсы тьы-ном были доступны в Университете Хо Ши Мин до 1993 г., и до сих пор это письмо изучают и преподают в Институте Хан Ном в Ханое, где недавно был опубликован словарь всех иероглифов тьы-ном.

В ХVII в. римские католические миссионеры представили систему письма на вьетнамском языке на латинской основе, куокнгы (Quốc Ngữ) (государственный язык), которая с тех пор и используется. До начала ХХ в. система письма куокнгы использовалась параллельно с тьы-ном. В наше время используется только куокнгы.

Вьетнамский алфавит и фонетическая транскрипция

Примечания

- Буквы «F», «J», «W» и «Z» не являются частью вьетнамского алфавита, но используются в иностранных заимствованных словах. «W» (vê-đúp)» иногда используется вместо «Ư» в сокращениях. В неофициальной переписке «W», «F», и «J» иногда используются как сокращения для «QU», «PH» и «GI» соответственно.

- Диграф «GH» и триграф «NGH», в основном, заменяют «G» и «NG» перед «I», чтобы не перепутать с диграфом «GI». По историческим причинам, они также используются перед «E» или «Ê».

- G = [ʒ] перед i, ê, и e, [ɣ] в другой позиции

- D и GI = [z] в северных диалектах (включая ханойский диалект), и [j] в центральных, южных и сайгонских диалектах.

- V произносится как [v] в северных диалектах, и [j] в южных диалектах.

- R = [ʐ, ɹ] в южных диалектах

Вьетнамский язык относится к тоновым языкам и насчитывает 6 тонов, которые обозначаются следующим образом:

Тоны:

1. ровный = призрак

2. высокий восходящий = щека

3. нисходящий = но

4. восходяще-нисходящий = могила

5. нисходяще-восходящий = лошадь

6. резко нисходящий = рисовый побег

|

Общие фразы |

||

|

цо, ванг, да |

||

|

Пожалуйста |

хонг цо чи |

|

|

Извините |

||

|

Здравствуйте |

||

|

До свидания |

||

|

Я не понял |

||

|

Как вас зовут? |

ten anh (chi) la gi? |

тен анх ла ги |

|

нья ве син |

||

|

Сколько это стоит? |

cai nay gia bao nhieu? |

цай най гиа бао нхиэу? |

|

Который час? |

may gio ro`i nhi? |

мау гио ро»и нхи? |

|

Вы говорите по-английски |

co noi tieng khong? |

цо ной тиенг хонг анх? |

|

Как это сказать? |

cai nay tieng noi the? |

цай най тиенг ной тэ? |

|

Я из России |

tôi đến từ Nga |

тои ден ту Нга |

|

Гостиница |

||

|

Магазин (покупки) |

||

|

Наличные |

||

|

Кредитная карточка |

thẻ tín dụng thẻ |

тэ тин дунг тэ |

|

Упаковать |

||

|

Без сдачи |

mà không cần dùng |

ма хонг сан дунг |

|

Очень дорого |

||

|

Транспорт |

||

|

Мотоцикл |

хэ ган май |

|

|

Аэропорт |

||

|

га хе луа |

||

|

Отправление |

ди, хо ханх |

|

|

Прибытие |

||

|

Экстренные случаи |

||

|

Пожарная служба |

sở cứu hỏa |

со суу хоа |

|

до»н цанх сат |

||

|

Скорая помощь |

xe cứu thương |

хэ суу хуонг |

|

Больница |

бенх виен |

|

|

хиеу туоц |

||

|

Ресторан |

||

|

нуоц трай цау |

||

|

Мороженое |

Язык Вьетнама

Какой язык во Вьетнаме

Официальный язык во Вьетнаме

— вьетнамский (тьенг вьет).

Вьетнамский язык широко распространен также в Камбодже, Лаосе, Таиланде, Малайзии, Австралии, Франции, Германии, США, Канаде. Во всем мире на нем говорят более 80 миллионов человек.

Язык Вьетнама

имеет особенности в разных регионах страны. Выделяется три основных диалекта: северных, центральный и южный.

Так как Ханой является городом с развитой туристической инфраструктурой, в отелях, ресторанах и кафе персонал владеет разговорным английским языком. В сфере обслуживания также в ходу французский и русские языки. Сложности перевода

русских путешественников в развитых туристических центрах Вьетнама обходят стороной.

Язык Вьетнама

имеет сложный фонологический строй. Одно слово, произнесенное разной интонацией и тоном, может иметь до шести значений.

Долгое время язык Вьетнама

находился под влиянием китайского языка. Две трети слов языка вьетов происходят от китайского языка, а в период французского владычества вьетнамская лексика обогатилась французскими словами.

До начала 20 века алфавит Вьетнама

был иероглифическим. Но чуть более столетие назад в стране было введено письмо на латинице. К латинским гласным буквам были добавлены диакритические знаки, обозначающие тон произношения буквы. Современный вьетнамский алфавит состоит из 29 букв.

Произношение вьетнамских слов и фраз в данном мини-разговорнике дается приближенно. Активно использовать эти слова и фразы не рекомендуется, так как при неправильной интонации смысл сказанного может быть сильно искажен. Это связано с тем, что вьетнамский язык является тоновым и казалось бы одно и то же слово, но, сказанное по разному, означает совсем разные вещи и понятия.

Звук «г» в конце слова произносится нечетко. Если написано два звука «а», то это значит просто удлиненное «а». Звук «х» после «т» произносится слабо.

В верхней части изображения надпись большими буквами на вьетнамском языке означает «Рынок Донг Суан» (Cho -рынок). В нижней части — «Вокзал Ханоя». Слово «ga» (вокзал) произошло от французского «gare».

Аэропорт, прибытие, контроль

Самолет — май бай

Паспорт — хо чьеу

Таможня — хай куаан

Иммиграционный контроль — ньяп каньг

Виза — тхии тук.

Стирка — жатдо (GIẶT ĐỒ)

В отеле

Отель — кхаак шан

Я бы хотел забронировать — лаам эн чо дой дат чыок моот

Можно посмотреть? — гой до те сэм фом дыок кхон?

С… до … (имеются в виду проживание с такого-то числа до такого-то) — ду … дэн …

Номер — со

Сколько стоит номер? Зья мот фом лаа боу ньеу?

Дата — нгай таанг

Мы съезжаем завтра — нгай май чунг дой зери дай

Кредитная карта — тхэ дин зун

Кондиционер — май лань

В ресторане

Ресторан — нья хан[г]

Я бы хотел — син чо дой

Говядина — тхьит бо

свинина — тхьит хейо

Курица — тхьит га

Рыба — каа

Орешки — дау фонг

Ложка — кай тхиа

Нож — гон зао

Вилка — кай ньиа

Числа

Туристам часто приходится иметь дело с числами.

Один — мот

Два — хай

Три — ба

Четыре — бон

Пять — нам

Шесть — шау

Семь — бай

Восемь — там

Девять — тин

Десять — мыой

Далее просто: 11 — десять и один=мыой мот, двенадцать=мыой хай и т.д. Только 15 будет не мыой нам, а мыой лам.

Двадцать — хай мыой (то есть, два десять) , 21 — хай мыой мот (два десять один).

Сто — мот чам, то есть одна сотня. 101 — мот чам лин мот, то есть, сто, затем что-то вроде нуля, затем один. 123 — мот чам хай мыой ба (одна сотня,

два десятка, три).

Тысяча — нгин, миллион — чиеу.

Процент — фан чам. 100% — мот чам фан чам.

Местоимения

Я — той, мой — ку:а той

Ты — кау ань или кау ти, в зависимости от того, к мужчине или женщине

обращаются (ань — мужчина, ти — женщина) твой — ку:а кау, а

также куа:ань, куа:ти

Вы — ань, ваш — ку:а ань

Он — ань_эй, ом_эй, ку:а

Она, её — ти_эй, ба_эй, ку:а, ти_эй,

ку:а ба_эй

Мы, наш — тюн[г]_та, тюн[г]_той,

ку:а тюн[г]_та, ку:а тюн[г]_той

Вы, ваш — как_ань (как_ти, как ом, как ба), ку:а как_ань (ку:а как_ти,

ку:а как ом, ку:а как ба)

Они, их — хо ку:а хо

Кто, чей — ай, ку:а ай

Что — зи, кай зи

Этот, та, это, эти — наи

Тот, та, то, те — кия

Приветствие

Здравствуйте — синь тяо (звук «т» произносится как среднее между «ч» и «т»). Это приветствие наиболее универсально и наиболее употребительно.

Его разновидности:

При обращении к мужчине до 40-45 лет — Тяо ань!

при обращении к женщине до 40-45 лет — Тяо ти!

при обращении к пожилому мужчине/пожилой женщине — Тяо ом!/Тяо ба!

… господин/госпожа — Тяо ом!/Тяо ба!

… друг — Тяо бан!

… при обращении к младшему по возрасту — Тяо эм!

… при обращении к ребенку — Тяо тяу!

При обращении к группе людей добавляется слово как

, обозначающее множественное число.

… при обращении к мужчинам — Тяо как_ань/как_ом! (в зависимости от возраста)

… при обращении к женщинам — Тяо как_ти/как_ба! (в зависимости от возраста)

… при обращении к мужчинам и женщинам, если присутствуют представители обоих

полов — Тяо как_ань, как_ти (как_ом, как_ба)!

… друзья (господа, господин и госпожа, товарищи) — Тяо как_бан (как_ом, ом_ба, как_дом_ти)!

До свидания — Там _биет ань! (вместо ань говорится ти, ом, ба и т.д., в зависимости от того, с кем прощаетесь). Но, так говорится в торжественных случаях. Более употребительным является просто «Тяо».

В городе

Скажите, пожалуйста — Лам_ын тё_бет…

Какой здесь адрес? Дьеа чии лаа зи?

Где находится банк — нган_хан[г] о:дау?

Ключевым здесь является слово где — о:дау?

Например: «Где вокзал?» — ня_га о:дау?

и так далее …

Магазин — кыа_хан[г]

Остановка автобуса — чам сэ_буит

Парикмахерская — хиеу кат_таук

Туалет — нья ве син

Стоянка такси — бэн так_си

Помогите мне, пожалуйста — лам_ын (пожалуйста) зуп (помогите) той (я, мне)

Напишите мне, пожалуйста — лам_ын (пожалуйста) виет хо (напишите) той (я, мне)

Повторите, пожалуйста, еще раз — син няк_лай мот лан ныа

Объясните, мне, пожалуйста — лам_ын зай_тхыть тё той

Разрешите спросить — тё_фэп той хой

Как это называется по-вьетнамски? — кай_наи тыен[г] вьет гой тхэ_нао?

Сто грамм — мот_чам (сто) гам (грамм)

Спасибо — кам_ын.

Большое спасибо — жэт кам_ын ань (вместо ань говорится ти, ом, ба и т.д., в зависимости от того, кого благодарите).

Общение

Извините — син_лой

Không can. Произносится как «(к)хом кан» — не надо, не нуждаюсь (категоричная форма).

Покупки, шоппинг — муа бан

Я (той) хочу (муон) примерить (мак_тхы)…

платье (ао_вай) это (най)

куан (брюки) най (эти)

юбку (вай) най (эту)

Сколько стоит? — Зао бао ньеу?

Очень дорого — дат куа

Нельзя ли дешевле? — ко жэ хын кхом?

Электронные разговорники

С развитием компактных электронных устройств в них начали «вшивать» программы голосового электронного перевода, кратко называемые электронными разговорниками. Этот же термин применяется и к самим устройствам, единственной функцией которых является устный электронный перевод.

Электронный перевод осуществляется и другими устройствами, например, смартфонами или планшетными компьютерами, если в них предусмотрена соотвествующая аппаратная и программная функциональность.

Электронные разговорники могут использоваться и в качестве мини-самоучителей иностранного языка.

Некоторые модели электронных разговорников содержат программы и словарные базы по переводу нескольких десятков языков в различных направлениях. Они особенно привлекательны для тех, кто много и часто путешествует по разным странам. Их стоимость находится в пределах $150-200.

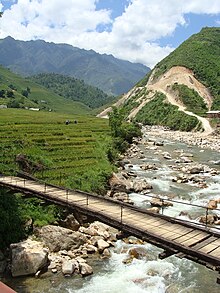

На каком языке говорят во Вьетнаме, интересуются все туристы, которые стремятся оказаться в этой стране. А в последнее время количество людей, которые отправляются в это юго-восточное государство, только увеличивается. Вьетнам привлекает экзотической природой, недорогим отдыхом и радушием местных жителей, с которыми хочется перекинуться хотя бы парой слов на их родном языке.

Официальный язык

Вьетнам — многонациональная страна. В ней существуют как официальный, так и непризнанные языки. Но все же, выясняя, на каком языке говорят во Вьетнаме, стоит признать, что большинство отдает предпочтение вьетнамскому. Он является государственным, при этом часть населения свободно общается на французском, английском и китайском языках.

Государственный язык Вьетнама служит для образования и межнационального общения. Помимо самого Вьетнама, он также распространен в Лаосе, Камбодже, Австралии, Малайзии, Таиланде, Германии, Франции, США, Германии, Канаде и других странах. Всего на нем говорят около 75 миллионов человек, из которых 72 млн проживают во Вьетнаме.

На этом языке во Вьетнаме разговаривают 86 процентов населения. Интересно, что до самого конца XIX века он преимущественно использовался только для бытового общения и написания художественных произведений.

История Вьетнама

Рассказывая, на каком языке говорят во Вьетнаме, нужно отметить, что на это наложила отпечаток история государства. Во II веке до нашей эры территория современной страны, которой посвящена эта статья, была завоевана Китаем. Фактически вьетнамцы оставались под протекторатом китайцев вплоть до X века. Именно по этой причине китайский язык служил основным для официального и письменного общения.

К тому же вьетнамские правители уделяли пристальное внимание конкурсным экзаменам при назначении нового чиновника на ту или иную должность. Это требовалось для отбора наиболее квалифицированных сотрудников, экзамены на протяжении нескольких веков проводились исключительно на китайском языке.

Как появился вьетнамский язык

Вьетнама в качестве самостоятельного литературного начал возникать только в конце XVII столетия. В то время французский монах-иезуит по имени Александр де Род разработал вьетнамский алфавит на основе латинского. В нем тоны обозначались особенными диакритическими значками.

Во второй половине XIX века колониальная администрация Франции, чтобы ослабить традиционное влияние китайского языка на Вьетнам, способствовала его развитию.

Современный литературный вьетнамский язык опирается на северный диалект ханойского говора. При этом письменная форма литературного языка основывается на звуковом составе центрального диалекта. Интересная особенность состоит в том, что на письме каждый слог отделяется пробелом.

Теперь вы знаете, какой язык во Вьетнаме. В наше время на нем говорит абсолютное большинство жителей этого государства. При этом, по оценкам специалистов, всего в стране около 130 языков, которые в большей или меньшей степени распространены на территории этой страны. Вьетнамский язык используется как средство общения на самом высоком уровне, а также среди простых людей. Это официальный язык в бизнесе и образовании.

Особенности вьетнамского языка

Зная, на каком языке говорят во Вьетнаме, стоит разобраться в его особенностях. Он относится к австроазиатской семье, вьетской группе. Скорее всего, по своему происхождению он близок к мыонгскому языку, однако изначально причислялся к группе тайских наречий.

У него большое количество диалектов, из которых выделяют три основных, каждый из которых делится на свои наречия и говоры. Северный диалект распространен в центре страны, в Хошимине и окружающих его районах популярен южный диалект. Все они различаются лексикой и фонетикой.

Грамматика

Всего во вьетнамском языке около двух с половиной тысяч слогов. Интересно, что их количество может меняться в зависимости от принадлежности к тому или иному диалекту. Это изолирующий язык, который в одно и то же время является тональным и слоговым.

Практически во всех языках этой группы сложные слова упрощаются до односложных, часто это касается и исторических слов, хотя в последнее время началась обратная тенденция. Во вьетнамском языке отсутствуют словоизменения и аналитические формы. То есть все грамматические отношения строятся исключительно на основе служебных слов, а приставки, суффиксы и аффиксы не играют в этом никакой роли. Знаменательные части речи включают в себя глаголы, прилагательные и предикативы. Еще одна отличительная особенность — это использование родственных терминов вместо личных местоимений.

Словообразование

Большинство слов в литературном вьетнамском языке образуются при помощи аффиксов, в основном имеющих китайское происхождение, а также сложения корней, удвоения слов или слогов.

Одна из ключевых особенностей словообразования заключается в том, что все компоненты, участвующие в образовании слов, являются односложными. Удивительно, но один слог может иметь сразу несколько значений, которые могут меняться от интонации при их произношении.

В предложении фиксированный порядок слов: сначала идет подлежащее, а затем сказуемое и дополнение. Большинство вьетнамских слов заимствованы из китайского языка, причем из разных исторических периодов, также много австроазиатской лексики.

Имена людей во Вьетнаме слагаются из трех слов — это фамилия матери или отца, прозвище и имя. По фамилии вьетов не называют, как в России, чаще всего их идентифицируют по имени. Еще одна особенность вьетнамских имен в прежние времена заключалась в том, что среднее имя явно указывало на пол ребенка при рождении. Причем если имя девочки состояло из одного слова, то у мальчика это могли быть несколько десятков слов. В наше время такая традиция исчезла.

Популярность вьетнамского языка

Из-за того, что в наше время на этом языке говорят во многих азиатских и европейских странах, неудивительно, что его популярность растет с каждым годом. Многие его учат для того, чтобы открыть бизнес в этом стремительно развивающемся государстве.

Определенные товары из Вьетнама сейчас не уступают ни в качестве, ни в стоимости, а культура и традиции настолько интересны и удивительны, что многие стремятся к ним приобщиться.

В самом Вьетнаме в сфере туризма активно используют английский, французский и китайский языки, достаточно много можно встретить русскоговорящий персонал, особенно среди тех, кто в советское время получал образование в СССР. Те, кто осваивает этот язык, отмечают, что он очень похож на китайский. В обоих языках слоги несут особую смысловую нагрузку, а интонации играют едва ли не решающую роль.

В России это достаточно редкий язык, существует всего несколько школ, которые помогут его освоить. Если вы все же решились его изучать, то будьте готовы к тому, что занятия могут начаться только после набора группы, возможно, ждать придется достаточно долго, поэтому лучше изначально ориентироваться на встречи с индивидуальным преподавателем.

Распространенные фразы на вьетнамском

Так что не так просто изучить этот язык. Общение в Вьетнаме при этом часто хочется построить на родном наречии, чтобы расположить к себе местных жителей. Не составляет большого труда освоить несколько популярных фраз, которые продемонстрируют в разговоре, насколько вы проникаете в местную культуру:

- Здравствуйте — син тяо.

- Дорогие друзья — как бан тхан мэйн.

- До свидания — хен гап лай нья.

- Где мы встретимся — тюнг та гап няу о дау?

- Пока — дди нхэ.

- Да — цо, ванг, да.

- Нет — хонг.

- Спасибо — кам он.

- Пожалуйста — хонг цо чи.

- Извините — хин лой.

- Как вас зовут — ань тэйн ла ди?

- Меня зовут… — той тэйн ла…

Надеемся, вы узнали много интересного о языке и культуре Вьетнама. Желаем интересных путешествий в эту страну!

Сегодня мы хотим поделится действительно полезными

фразами на вьетнамском языке. Это будет очень полезно, когда вы по приезду во

Вьетнам, придете, например, на рынок или в магазин. Вьетнамцы в основном не

знают английского, скорее они будут знать несколько слов на русском. Однако,

если вы покажете своим знанием некоторых фраз уважение к их культуре и стране,

это поможет вам снизить цену и расположить их к себе.

Вьетнамский язык очень сложен для восприятия «на

слух», поскольку в нем содержится много гласных и каждая из них может содержать

6 тональностей. Надо обладать почти музыкальным слухом, чтобы уловить все эти

тонкости. Для вьетнамцев же крайне сложен русский язык, потому что содержит много

твердых, шипящих и звонких согласных. Но мы не будем лишний раз забивать голову

и представляем вам несколько действительно полезных фраз:

«Здравствуйте» —

син тяо

«До свидания» —

там биет

«Да» — да

«Нет» — хонг

«Спасибо» — КАМ ОН

«Большое спасибо» — КАМ ОН НИЕ»У

«Сколько стоит?» — бао НИЕ»У

«Лед» — да

«Хлеб» — бан ми

«Чай со льдом» — ча да

«Кофе со льдом и сгущенкой» — кафе сю да

«Счет» — Тинь тиен

Обращение к официанту или к кому либо — эм ой

«Рис» — ком

«Рыба» — ка

«Курица» — га

«Говядина» — бо Ноль Хонг

«Один» -Мот

«Два» — Хай

«Три» — Ба

«Четыре» — Бон

«Пять» — Нам

«Шесть» — Сау

«Семь» — Бай

«Восемь» — Там

«Девять» — Тьен

«Десять» — Муой

Вьетнамский язык очень сложный, так как гласные буквы в нем имеют разные тональности, именно поэтому русско-вьетнамский разговорник для туристов включает в себя минимум слов. Русско-вьетнамский разговорник пригодится вам на местных рынках и в ресторанах, но имейте в виду, что человек, незнакомый с правилами вьетнамского произношения, будет говорить с сильным акцентом и может быть не понят. В туристический зонах к этому привыкли и обычно понимают простые фразы, сказанные иностранцами, стоит же вам уехать в отдаленные от курортов места, вам будет намного сложнее изъясняться, даже используя русско-вьетнамский разговорник.

Русско-вьетнамский разговорник: зачем он нужен

Используйте наш коротенький русско-вьетнамский разговорник, ведь если вьетнамцам удастся вас понять, они будут очень рады этому, отнесутся к к вам с большой теплотой и дадут вам скидки больше, чем дают обычно.

Русско-вьетнамский разговорник: приветствие и прощание

Вьетнамцы, здороваясь между собой, обычно акцентируют внимание на том, к кому они обращаются. В зависимости от возраста и пола, приветствие может звучать по-разному. Но, чтобы не путаться в обращениях, наш русско-вьетнамский разговорник предлагает вам единое общее приветствие, которое подойдет для всех: Xin chào

(Синь чао). Приходя в любое кафе или лавочку скажите «Син чао», это очень порадует вьетнамцев.

Попрощаться можно, используя слово Tạm biệt

(Там бьет). Это выражение подходит для мест, в которые вы можете не вернуться (означает скорее «прощайте»). Если вам хочется быть еще вежливее и обозначить возможность новой встречи, можно сказать Hẹn gặp lại

(Хэн гап лай), которую можно перевести на русский язык как «увидимся, до встречи».

Какое слово самое полезное в любой стране после приветствия? Ну конечно же, это слово «спасибо». По-вьетнамски оно звучит как Cảm ơn

(Кам он). Запомнить его очень легко, так как многим знакомо английское выражение, звучащее схожим образом, но означающее совершенно иное =)

Если в ответ на ваше спасибо, вы услышите слова Không có gì

(Хон ко чи), это означает «не за что».

Русско-вьетнамский разговорник: в ресторане

В ресторане вам пригодится следующий мини русско-вьетнамский разговорник.

Для того, чтобы узнать какое из блюдо лучше заказать, задайте официанту вопрос Món gì ngon?

(Мон зи нён). Это фраза будет примерно равнозначна русскому вопросу — «Какое из блюд хорошее?».

Кушая во вьетнамском кафе, вам обязательно захочется поблагодарить повара и выразить свои мысли по-поводы еды. Вьетнамские кушанья могут быть абсолютно простыми, такими как рис с курицей или суп с лапшой, а могут быть экзотическими и замысловатыми, например, суп из ласточкиных гнезд или барбекю из крокодила. В любой случае эта еда будет очень вкусной! Сказать об этом можно, используя простую фразу Ngon quá!

(Нон ква), которая означает в переводе «очень вкусно».

Чтобы попросить счет, скажите: Tính tiền

(Тинь тьен), официант должен понять вас и рассчитать.

Русско-вьетнамский разговорник: на рынке

Для того, чтобы легче было ориентироваться на рынке, нужно знать цифры:

- один — một

(мот) - два — hai

(хай) - три — ba

(ба) - четыре — bốn

(бон) - пять — năm

(нам) - шесть — sáu

(сау) - семь — bảy

(бай) - восемь — tám

(там) - девять — chín

(чинь) - десять — mười

(муй)

Для того, чтобы торговаться, достаточно будет одного элементарного đắt quá

(Дат ква) — очень дорого. Для удобства вы можете назначать свою цену, пользуясь калькулятором, он должен быть у каждого продавца.

Остается добавить, что если вы не знаете ни слова по вьетнамски — это тоже не страшно. На территории большинства курортов вьетнамцы говорят на английском или даже русском языках (в Муйне на русском говорит большинство продавцов, менеджеров и администраторов), поэтому у вас вряд ли возникнут трудности при общении.

→

вьетнамский — прилагательное, именительный п., муж. p., ед. ч.

↳

вьетнамский — прилагательное, винительный п., муж. p., ед. ч.

Часть речи: прилагательное

Положительная степень:

| Единственное число | Множественное число | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Мужской род | Женский род | Средний род | ||

| Им. |

вьетнамский |

вьетнамская |

вьетнамское |

вьетнамские |

| Рд. |

вьетнамского |

вьетнамской |

вьетнамского |

вьетнамских |

| Дт. |

вьетнамскому |

вьетнамской |

вьетнамскому |

вьетнамским |

| Вн. |

вьетнамского вьетнамский |

вьетнамскую |

вьетнамское |

вьетнамские вьетнамских |

| Тв. |

вьетнамским |

вьетнамскою вьетнамской |

вьетнамским |

вьетнамскими |

| Пр. |

вьетнамском |

вьетнамской |

вьетнамском |

вьетнамских |

Если вы нашли ошибку, пожалуйста, выделите фрагмент текста и нажмите Ctrl+Enter.

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

Corpus name: OpenSubtitles2018. License: not specified. References: http://opus.nlpl.eu/OpenSubtitles2018.php, http://stp.lingfil.uu.se/~joerg/paper/opensubs2016.pdf

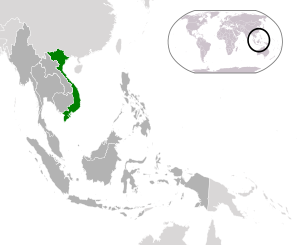

Coordinates: 16°N 108°E / 16°N 108°E

|

Socialist Republic of Vietnam Cộng hòa Xã hội chủ nghĩa Việt Nam (Vietnamese) |

|

|---|---|

|

Flag Emblem |

|

| Motto: Độc lập – Tự do – Hạnh phúc

«Independence – Liberty – Happiness» |

|

| Anthem: Tiến Quân Ca «Army March» |

|

|

Location of Vietnam (green) in ASEAN (dark grey) |

|

| Capital | Hanoi 21°2′N 105°51′E / 21.033°N 105.850°E |

| Largest city | Ho Chi Minh City 10°48′N 106°39′E / 10.800°N 106.650°E |

| Official language | Vietnamese (de facto)[n 1] |

| Ethnic groups

(2019) |

|

| Religion

(2019) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Vietnamese |

| Government | Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic |

|

• General Secretary |

Nguyễn Phú Trọng |

|

• President |

Võ Văn Thưởng |

|

• Prime Minister |

Phạm Minh Chính |

|

• National Assembly Chairman |

Vương Đình Huệ |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Formation | |

|

• Independence from China |

1 February 939 |

|

• First empire |

968 |

|

• Annexation of Panduranga |

1832 |

|

• Protectorate Treaty |

25 August 1883 |

|

• Declaration of Independence |

2 September 1945 |

|

• North-South division |

21 July 1954 |

|

• End of Vietnam War |

30 April 1975 |

|

• Reunification |

2 July 1976 |

|

• Đổi Mới |

18 December 1986 |

|

• Current constitution |

28 November 2013[n 2] |

| Area | |

|

• Total |

331,699 km2 (128,070 sq mi) (66th) |

|

• Water (%) |

6.38 |

| Population | |

|

• 2022 estimate |

99,460,000[5] (15th) |

|

• 2019 census |

96,208,984[2] |

|

• Density |

295.0/km2 (764.0/sq mi) (29th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

|

• Total |

|

|

• Per capita |

|

| Gini (2018) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | high · 115th |

| Currency | đồng (₫) (VND) |

| Time zone | UTC+07:00 (Vietnam Standard Time) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +84 |

| ISO 3166 code | VN |

| Internet TLD | .vn |

Vietnam or Viet Nam[n 3] (Vietnamese: Việt Nam, [vîət nāːm] (listen)), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,[n 4] is a country in Southeast Asia. It is located at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of 311,699 square kilometres (120,348 sq mi) and population of 96 million, making it the world’s sixteenth-most populous country. Vietnam borders China to the north, and Laos and Cambodia to the west. It shares maritime borders with Thailand through the Gulf of Thailand, and the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia through the South China Sea. Its capital is Hanoi and its largest city is Ho Chi Minh City (commonly referred to by its former name, Saigon).

Vietnam was inhabited by the Paleolithic age, with states established in the first millennium BC on the Red River Delta in modern-day northern Vietnam. The Han dynasty annexed Northern and Central Vietnam under Chinese rule from 111 BC, until the first dynasty emerged in 939. Successive monarchical dynasties absorbed Chinese influences through Confucianism and Buddhism, and expanded southward to the Mekong Delta, conquering Champa. The Nguyễn—the last imperial dynasty—surrendered to France in 1883. Following the August Revolution, the nationalist Viet Minh under the leadership of communist revolutionary Ho Chi Minh proclaimed independence from France in 1945.

Vietnam went through prolonged warfare in the 20th century. After World War II, France returned to reclaim colonial power in the First Indochina War, from which Vietnam emerged victorious in 1954. As a result of treaties signed two years later, Vietnam was also separated into two parts. The Vietnam War began shortly after, between the communist North, supported by the Soviet Union and China, and the anti-communist South, supported by the United States. Upon the North Vietnamese victory in 1975, Vietnam reunified as a unitary socialist state under the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) in 1976. An ineffective planned economy, a trade embargo by the West, and wars with Cambodia and China crippled the country further. In 1986, the CPV initiated economic and political reforms similar to the Chinese economic reform, transforming the country to a market-oriented economy. The reforms facilitated Vietnamese reintegration into the global economy and politics.

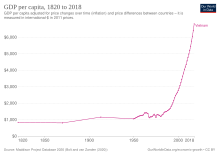

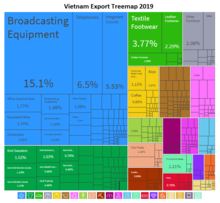

A developing country with a lower-middle-income economy, Vietnam is nonetheless one of the fastest-growing economies of the 21st century, with a GDP predicted to rival developed nations by 2050. Vietnam has high levels of corruption and censorship and a poor human rights record; the country ranks among the lowest in international measurements of civil liberties, freedom of the press, and freedom of religion and ethnic minorities. It is part of international and intergovernmental institutions including the ASEAN, the APEC, the CPTPP, the Non-Aligned Movement, the OIF, and the WTO. It has assumed a seat on the United Nations Security Council twice.

Etymology

The name Việt Nam (Vietnamese pronunciation: [viə̀t naːm], chữ Hán: 越南), literally “Viet south”, means “Viet of the South” per Vietnamese word order or “South of the Viet” per Classical Chinese word order.[9] A variation of the name, Nanyue (or Nam Việt, 南越), was first documented in the 2nd century BC.[10] The term «Việt» (Yue) (Chinese: 越; pinyin: Yuè; Cantonese Yale: Yuht; Wade–Giles: Yüeh4; Vietnamese: Việt) in Early Middle Chinese was first written using the logograph «戉» for an axe (a homophone), in oracle bone and bronze inscriptions of the late Shang dynasty (c. 1200 BC), and later as «越».[11] At that time it referred to a people or chieftain to the northwest of the Shang.[12] In the early 8th century BC, a tribe on the middle Yangtze were called the Yangyue, a term later used for peoples further south.[12] Between the 7th and 4th centuries BC Yue/Việt referred to the State of Yue in the lower Yangtze basin and its people.[11][12] From the 3rd century BC the term was used for the non-Chinese populations of southern China and northern Vietnam, with particular ethnic groups called Minyue, Ouyue, Luoyue (Vietnamese: Lạc Việt), etc., collectively called the Baiyue (Bách Việt, Chinese: 百越; pinyin: Bǎiyuè; Cantonese Yale: Baak Yuet; Vietnamese: Bách Việt; «Hundred Yue/Viet»; ).[11][12][13] The term Baiyue/Bách Việt first appeared in the book Lüshi Chunqiu compiled around 239 BC.[14] By the 17th and 18th centuries AD, educated Vietnamese apparently referred to themselves as nguoi Viet (Viet people) or nguoi nam (southern people).[15]

The form Việt Nam (越南) is first recorded in the 16th-century oracular poem Sấm Trạng Trình. The name has also been found on 12 steles carved in the 16th and 17th centuries, including one at Bao Lam Pagoda in Hải Phòng that dates to 1558.[16] In 1802, Nguyễn Phúc Ánh (who later became Emperor Gia Long) established the Nguyễn dynasty. In the second year of his rule, he asked the Jiaqing Emperor of the Qing dynasty to confer on him the title ‘King of Nam Việt / Nanyue’ (南越 in Chinese character) after seizing power in Annam. The Emperor refused because the name was related to Zhao Tuo’s Nanyue, which included the regions of Guangxi and Guangdong in southern China. The Qing Emperor, therefore, decided to call the area «Việt Nam» instead,[n 5][18] meaning “South of the Viet” per Classical Chinese word order but the Vietnamese understood it as “Viet of the South” per Vietnamese word order.[9] Between 1804 and 1813, the name Vietnam was used officially by Emperor Gia Long.[n 5] It was revived in the early 20th century in Phan Bội Châu’s History of the Loss of Vietnam, and later by the Vietnamese Nationalist Party (VNQDĐ).[19] The country was usually called Annam until 1945, when the imperial government in Huế adopted Việt Nam.[20]

History

Prehistory and early history

Archaeological excavations have revealed the existence of humans in what is now Vietnam as early as the Paleolithic age. Stone artefacts excavated in Gia Lai province have been claimed to date to 0.78 Ma,[21] based on associated find of tektites, however this claim has been challenged because tektites are often found in archaeological sites of various ages in Vietnam.[22] Homo erectus fossils dating to around 500,000 BC have been found in caves in Lạng Sơn and Nghệ An provinces in northern Vietnam.[23] The oldest Homo sapiens fossils from mainland Southeast Asia are of Middle Pleistocene provenance, and include isolated tooth fragments from Tham Om and Hang Hum.[24][25][26] Teeth attributed to Homo sapiens from the Late Pleistocene have been found at Dong Can,[27] and from the Early Holocene at Mai Da Dieu,[28][29] Lang Gao[30][31] and Lang Cuom.[32] By about 1,000 BC, the development of wet-rice cultivation in the Ma River and Red River floodplains led to the flourishing of Đông Sơn culture,[33][34] notable for its bronze casting used to make elaborate bronze Đông Sơn drums.[35][36][37] At this point, the early Vietnamese kingdoms of Văn Lang and Âu Lạc appeared, and the culture’s influence spread to other parts of Southeast Asia, including Maritime Southeast Asia, throughout the first millennium BC.[36][38]

Dynastic Vietnam

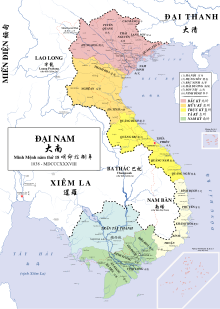

Vietnam’s territories around 1838

According to Vietnamese legends, Hồng Bàng dynasty of the Hùng kings first established in 2879 BC is considered the first state in the history of Vietnam (then known as Xích Quỷ and later Văn Lang).[39][40] In 257 BC, the last Hùng king was defeated by Thục Phán. He consolidated the Lạc Việt and Âu Việt tribes to form the Âu Lạc, proclaiming himself An Dương Vương.[41] In 179 BC, a Chinese general named Zhao Tuo («Triệu Đà») defeated An Dương Vương and consolidated Âu Lạc into Nanyue.[34] However, Nanyue was itself incorporated into the empire of the Chinese Han dynasty in 111 BC after the Han–Nanyue War.[18][42] For the next thousand years, what is now northern Vietnam remained mostly under Chinese rule.[43][44] Early independence movements, such as those of the Trưng Sisters and Lady Triệu,[45] were temporarily successful,[46] though the region gained a longer period of independence as Vạn Xuân under the Anterior Lý dynasty between AD 544 and 602.[47][48][49] By the early 10th century, Northern Vietnam had gained autonomy, but not sovereignty, under the Khúc family.[50]

In AD 938, the Vietnamese lord Ngô Quyền defeated the forces of the Chinese Southern Han state at Bạch Đằng River and achieved full independence for Vietnam in 939 after a millennium of Chinese domination.[51][52][53] By the 960s, the dynastic Đại Việt (Great Viet) kingdom was established, Vietnamese society enjoyed a golden era under the Lý and Trần dynasties. During the rule of the Trần Dynasty, Đại Việt repelled three Mongol invasions.[54][55] Meanwhile, the Mahāyāna branch of Buddhism flourished and became the state religion.[53][56] Following the 1406–7 Ming–Hồ War, which overthrew the Hồ dynasty, Vietnamese independence was interrupted briefly by the Chinese Ming dynasty, but was restored by Lê Lợi, the founder of the Lê dynasty.[57] The Vietnamese polity reached their zenith in the Lê dynasty of the 15th century, especially during the reign of emperor Lê Thánh Tông (1460–1497).[58][59] Between the 11th and 18th centuries, the Vietnamese polity expanded southward in a gradual process known as Nam tiến («Southward expansion»),[60] eventually conquering the kingdom of Champa and part of the Khmer Kingdom.[61][62][63]

From the 16th century onward, civil strife and frequent political infighting engulfed much of Dai Viet. First, the Chinese-supported Mạc dynasty challenged the Lê dynasty’s power.[64] After the Mạc dynasty was defeated, the Lê dynasty was nominally reinstalled. Actual power, however, was divided between the northern Trịnh lords and the southern Nguyễn lords, who engaged in a civil war for more than four decades before a truce was called in the 1670s.[65] Vietnam was divided into North (Trịnh) and South (Nguyễn) from 1600 to 1777. During this period, the Nguyễn expanded southern Vietnam into the Mekong Delta, annexing the Central Highlands and the Khmer lands in the Mekong Delta.[61][63][66] The division of the country ended a century later when the Tây Sơn brothers helped Trịnh to end Nguyễn, they also established new dynasty and ended Trịnh. However, their rule did not last long, and they were defeated by the remnants of the Nguyễn lords, led by Nguyễn Ánh. Nguyễn Ánh unified Vietnam, and established the Nguyễn dynasty, ruling under the name Gia Long.[66]

French Indochina

In the 1500s, the Portuguese explored the Vietnamese coast and reportedly erected a stele on the Chàm Islands to mark their presence.[67] By 1533, they began landing in the Vietnamese delta but were forced to leave because of local turmoil and fighting. They also had less interest in the territory than they did in China and Japan.[67] After they had settled in Macau and Nagasaki to begin the profitable Macau–Japan trade route, the Portuguese began to involve themselves in trade with Hội An.[67] Portuguese traders and Jesuit missionaries under the Padroado system were active in both Vietnamese realms of Đàng Trong (Cochinchina or Quinan) and Đàng Ngoài (Tonkin) in the 17th century.[68] The Dutch also tried to establish contact with Quinan in 1601 but failed to sustain a presence there after several violent encounters with the locals. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) only managed to establish official relations with Tonkin in the spring of 1637 after leaving Dejima in Japan to establish trade for silk.[69] Meanwhile, in 1613, the first English attempt to establish contact with Hội An failed following a violent incident involving the Honourable East India Company. By 1672 the English did establish relations with Tonkin and were allowed to reside in Phố Hiến.[70]

Between 1615 and 1753, French traders also engaged in trade in Vietnam.[71][72] The first French missionaries arrived in 1658, under the Portuguese Padroado. From its foundation, the Paris Foreign Missions Society under Propaganda Fide actively sent missionaries to Vietnam, entering Cochinchina first in 1664 and Tonkin first in 1666.[73] Spanish Dominicans joined the Tonkin mission in 1676, and Franciscans were in Cochinchina from 1719 to 1834. The Vietnamese authorities began[when?] to feel threatened by continuous Christianisation activities.[74] After several Catholic missionaries were detained, the French Navy intervened in 1843 to free them, as the kingdom was perceived as xenophobic.[75] In a series of conquests from 1859 to 1885, France eroded Vietnam’s sovereignty.[76] At the siege of Tourane in 1858, France was aided by Spain (with Filipino, Latin American, and Spanish troops from the Philippines)[77] and perhaps some Tonkinese Catholics.[78] After the 1862 Treaty, and especially after France completely conquered Lower Cochinchina in 1867, the Văn Thân movement of scholar-gentry class arose and committed violence against Catholics across central and northern Vietnam.[79]

Between 1862 and 1867, the southern third of the country became the French colony of Cochinchina.[80] By 1884, the entire country was under French rule, with the central and northern parts of Vietnam separated into the two protectorates of Annam and Tonkin. The three entities were formally integrated into the union of French Indochina in 1887.[81][82] The French administration imposed significant political and cultural changes on Vietnamese society.[83] A Western-style system of modern education introduced new humanist values.[84] Most French settlers in Indochina were concentrated in Cochinchina, particularly in Saigon, and in Hanoi, the colony’s capital.[85]

During the colonial period, guerrillas of the royalist Cần Vương movement rebelled against French rule and massacred around a third of Vietnam’s Christian population.[86][87] After a decade of resistance, they were defeated in the 1890s by the Catholics in reprisal for their earlier massacres.[88][89] Another large-scale rebellion, the Thái Nguyên uprising, was also suppressed heavily.[90] The French developed a plantation economy to promote export of tobacco, indigo, tea and coffee.[91] However, they largely ignored the increasing demands for civil rights and self-government.

A nationalist political movement soon emerged, with leaders like Phan Bội Châu, Phan Châu Trinh, Phan Đình Phùng, Emperor Hàm Nghi, and Hồ Chí Minh fighting or calling for independence.[92] This resulted in the 1930 Yên Bái mutiny by the Vietnamese Nationalist Party (VNQDĐ), which the French quashed. The mutiny split the independence movement, as many leading members converted to communism.[93][94][95]

The French maintained full control of their colonies until World War II, when the war in the Pacific led to the Japanese invasion of French Indochina in 1940. Afterwards, the Japanese Empire was allowed to station its troops in Vietnam while the pro-Vichy French colonial administration continued.[96][97] Japan exploited Vietnam’s natural resources to support its military campaigns, culminating in a full-scale takeover of the country in March 1945. This led to the Vietnamese Famine of 1945 which killed up to two million people.[98][99]

First Indochina War