Contdict.com > Русско латинский переводчик онлайн

ё

й

ъ

ь

Русско-латинский словарь

|

|

|

|

ветрянка:

|

Chickenpox |

Примеры перевода «ветрянка» в контексте:

|

Правая ветрянка воротной вены |

Pullum pox ius porta venam Источник пожаловаться Langcrowd.com |

Популярные направления онлайн-перевода:

Английский-Латынь Английский-Русский Итальянский-Латынь Китайский-Русский Латынь-Английский Латынь-Итальянский Латынь-Немецкий Латынь-Русский Русский-Английский Русский-Китайский

© 2023 Contdict.com — онлайн-переводчик

Privacy policy

Terms of use

Contact

ResponsiveVoice-NonCommercial licensed under (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)

оспа ветряная

-

1

оспаБольшой русско-английский медицинский словарь > оспа

-

2

оспаRussian-english stomatological dctionary > оспа

-

3

оспаРусско-греческий словарь > оспа

-

4

ветряная оспаРусско-английский синонимический словарь > ветряная оспа

-

5

оспаРусско-башкирский словарь > оспа

-

6

ветряная оспаРусско-английский словарь нормативно-технической терминологии > ветряная оспа

-

7

оспаБольшой англо-русский и русско-английский словарь > оспа

-

8

оспаБФРС > оспа

-

9

оспаРусско-английский словарь Смирнитского > оспа

-

10

оспаРусско-английский словарь по общей лексике > оспа

-

11

оспао́сп||а

жἡ εὐλογία, ἡ εὐλογιά, ἡ βλο-γιά:

ветряная оспа ἡ ἀνεμοβλογιά· черная оспа ἡ αίμορραγική εὐλογιά· прививать оспау κάνω ἐμβόλιο κατά τής εὐλογιάς· лицо в оспае πρόσωπο βλογιοκομμένο.

Русско-новогреческий словарь > оспа

-

12

оспаж

1. мед. нағзак; чёрная оспа нағзаки сиёҳ; болеть оспой нағзак баровардан; привить оспу нағзак канондан

2. разг. доғи нағзак <> ветряная оспа гулафшон, гул, нағзак, обакон

Русско-таджикский словарь > оспа

-

13

оспа••

2) buttero м.

* * *

лицо в о́спе — il viso butterato

* * *

n

Universale dizionario russo-italiano > оспа

-

14

оспаРусско-белорусский словарь > оспа

-

15

оспаж

приви́ть о́спу кому-л. — vaccinate (against smallpox)

Американизмы. Русско-английский словарь. > оспа

-

16

оспаНовый русско-итальянский словарь > оспа

-

17

оспа-ы, сущ. ж. I, мн. ч. нет цецг гем, цоохр гем; ветряная оспа цаһан алхц

Русско-калмыцкий словарь > оспа

-

18

оспаРусско-греческий словарь научных и технических терминов > оспа

-

19

ветряная оспаБольшой англо-русский и русско-английский словарь > ветряная оспа

-

20

ветряная оспаБНРС > ветряная оспа

Страницы

- Следующая →

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

См. также в других словарях:

-

ОСПА ВЕТРЯНАЯ — мед. Ветряная оспа высококонтагиозное острое вирусное инфекционное заболевание, протекающее с умеренно выраженной интоксикацией и характерной полиморфной сыпью на коже и слизистых оболочках. Этиология Возбудитель ДНК содержащий вирус (Varicella… … Справочник по болезням

-

оспа ветряная — (varicella) острая инфекционная болезнь, вызываемая вирусом ветряной оспы, передающимся воздушно капельным путем; клинически проявляется папуловезикулезной сыпью на коже и повышением температуры; чаще болеют дети до 10 лет … Большой медицинский словарь

-

оспа ветряная — острая инфекционная болезнь, вызываемая вирусом ветряной оспы, передающимся воздушно капельным путем, клинически проявляется папуловезикулезной сыпью на коже и повышением температуры; чаще болеют дети до 10 лет. Источник: Медицинская Популярная… … Медицинские термины

-

Оспа Ветряная (Varicella) — см. Ветрянка. Источник: Медицинский словарь … Медицинские термины

-

ОСПА — ОСПА, оспы, мн. нет, жен. Тяжелая заразная болезнь, сопровождающаяся появлением гнойной сыпи на коже и слизистых оболочках, неизгладимо уродующая кожу. Натуральная оспа. Черная оспа. «В комнату вошел человек лет пятидесяти, с бледным, изрытым… … Толковый словарь Ушакова

-

Ветряная оспа — У этого термина существуют и другие значения, см. Оспа. Ветряная оспа … Википедия

-

ОСПА НАТУРАЛЬНАЯ — мед. Натуральная оспа острая вирусная инфекция, протекавшая с выраженной интоксикацией и кожными высыпаниями. Этиология Возбудитель вирус натуральной оспы рода Orthopoxvirus. Известно 2 штамма вируса: первый вызывает классическую оспу (variola… … Справочник по болезням

-

ветряная оспа — ветрянка (разг.) Словарь синонимов русского языка. Практический справочник. М.: Русский язык. З. Е. Александрова. 2011. ветряная оспа сущ., кол во синонимов: 2 • болезнь … Словарь синонимов

-

ВЕТРЯНАЯ ОСПА — ВЕТРЯНАЯ ОСПА, ветрянка (varicella), представляет собой острое инфекционное заболевание, сопровождающееся пятнисто пузырчатой сыпью. Она контагиозна и при нимает часто эпид. течение. Б нь эта присуща детскому возрасту до 10 лет, у старших детей… … Большая медицинская энциклопедия

-

ОСПА — ОСПА, воспа жен. сыпная повальная болезнь на людей и на животных, напр. на овец, кои мрут от нее поголовно. На людях, оспа бывает: природная, прививная (коровья), и ветряная или ветрянка. Оспа ходит по ночам, с совиными очами, с железным клювом,… … Толковый словарь Даля

-

ВЕТРЯНАЯ ОСПА — острое вирусное заболевание преимущественно детей с лихорадкой и сыпью в виде пузырьков, подсыхающих в корочки. Заражение от больного через воздух … Большой Энциклопедический словарь

| Chickenpox | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Varicella |

|

|

| A boy presenting with the characteristic blisters of chickenpox | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Small, itchy blisters, headache, loss of appetite, tiredness, fever[1] |

| Usual onset | 10–21 days after exposure[2] |

| Duration | 5–10 days[1] |

| Causes | Varicella zoster virus[3] |

| Prevention | Varicella vaccine[4] |

| Medication | Calamine lotion, paracetamol (acetaminophen), aciclovir[5] |

| Deaths | 6,400 per year (with shingles)[6] |

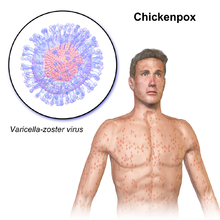

Chickenpox, also known as varicella, is a highly contagious disease caused by the initial infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV).[3] The disease results in a characteristic skin rash that forms small, itchy blisters, which eventually scab over.[1] It usually starts on the chest, back, and face.[1] It then spreads to the rest of the body.[1] The rash and other symptoms, such as fever, tiredness, and headaches, usually last five to seven days.[1] Complications may occasionally include pneumonia, inflammation of the brain, and bacterial skin infections.[7] The disease is usually more severe in adults than in children.[8]

Chickenpox is an airborne disease which spreads easily from one person to the next through the coughs and sneezes of an infected person.[5] The incubation period is 10–21 days, after which the characteristic rash appears.[2] It may be spread from one to two days before the rash appears until all lesions have crusted over.[5] It may also spread through contact with the blisters.[5] Those with shingles may spread chickenpox to those who are not immune through contact with the blisters.[5] The disease can usually be diagnosed based on the presenting symptom;[9] however, in unusual cases it may be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of the blister fluid or scabs.[8] Testing for antibodies may be done to determine if a person is immune.[8] People usually only get chickenpox once.[5] Although reinfections by the virus occur, these reinfections usually do not cause any symptoms.[10]

Since its introduction in 1995, the varicella vaccine has resulted in a decrease in the number of cases and complications from the disease.[4] It protects about 70–90 percent of people from disease with a greater benefit for severe disease.[8] Routine immunization of children is recommended in many countries.[11] Immunization within three days of exposure may improve outcomes in children.[12] Treatment of those infected may include calamine lotion to help with itching, keeping the fingernails short to decrease injury from scratching, and the use of paracetamol (acetaminophen) to help with fevers.[5] For those at increased risk of complications, antiviral medication such as aciclovir are recommended.[5]

Chickenpox occurs in all parts of the world.[8] In 2013 there were 140 million cases of chickenpox and shingles worldwide.[13] Before routine immunization the number of cases occurring each year was similar to the number of people born.[8] Since immunization the number of infections in the United States has decreased nearly 90%.[8] In 2015 chickenpox resulted in 6,400 deaths globally – down from 8,900 in 1990.[6][14] Death occurs in about 1 per 60,000 cases.[8] Chickenpox was not separated from smallpox until the late 19th century.[8] In 1888 its connection to shingles was determined.[8] The first documented use of the term chicken pox was in 1658.[15] Various explanations have been suggested for the use of «chicken» in the name, one being the relative mildness of the disease.[15]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

A single blister, typical during the early stages of the rash

The early (prodromal) symptoms in adolescents and adults are nausea, loss of appetite, aching muscles, and headache.[16] This is followed by the characteristic rash or oral sores, malaise, and a low-grade fever that signal the presence of the disease. Oral manifestations of the disease (enanthem) not uncommonly may precede the external rash (exanthem). In children the illness is not usually preceded by prodromal symptoms, and the first sign is the rash or the spots in the oral cavity. The rash begins as small red dots on the face, scalp, torso, upper arms and legs; progressing over 10–12 hours to small bumps, blisters and pustules; followed by umbilication and the formation of scabs.[17][18]

At the blister stage, intense itching is usually present. Blisters may also occur on the palms, soles, and genital area. Commonly, visible evidence of the disease develops in the oral cavity and tonsil areas in the form of small ulcers which can be painful or itchy or both; this enanthem (internal rash) can precede the exanthem (external rash) by 1 to 3 days or can be concurrent. These symptoms of chickenpox appear 10 to 21 days after exposure to a contagious person. Adults may have a more widespread rash and longer fever, and they are more likely to experience complications, such as varicella pneumonia.[17]

Because watery nasal discharge containing live virus usually precedes both exanthem (external rash) and enanthem (oral ulcers) by 1 to 2 days, the infected person actually becomes contagious one to two days before recognition of the disease. Contagiousness persists until all vesicular lesions have become dry crusts (scabs), which usually entails four or five days, by which time nasal shedding of live virus ceases.[19] The condition usually resolves by itself within a week or two.[20] The rash may, however, last for up to one month.[medical citation needed][21]

Chickenpox is rarely fatal, although it is generally more severe in adult men than in women or children. Non-immune pregnant women and those with a suppressed immune system are at highest risk of serious complications. Arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) associated with chickenpox in the previous year accounts for nearly one third of childhood AIS.[22] The most common late complication of chickenpox is shingles (herpes zoster), caused by reactivation of the varicella zoster virus decades after the initial, often childhood, chickenpox infection.[21]

-

The back of a 30-year-old male after five days of the rash

-

A 3-year-old girl with a chickenpox rash on her torso

-

Lower leg of a child with chickenpox

-

A child with chickenpox

-

A child with chickenpox on her face.

-

A child with chickenpox

-

Chickenpox blister closeup, day 7 after start of fever

Pregnancy and neonates[edit]

During pregnancy the dangers to the fetus associated with a primary VZV infection are greater in the first six months. In the third trimester, the mother is more likely to have severe symptoms.[23]

For pregnant women, antibodies produced as a result of immunization or previous infection are transferred via the placenta to the fetus.[24]

Varicella infection in pregnant women could lead to spread via the placenta and infection of the fetus. If infection occurs during the first 28 weeks of gestation, this can lead to fetal varicella syndrome (also known as congenital varicella syndrome).[25] Effects on the fetus can range in severity from underdeveloped toes and fingers to severe anal and bladder malformation.[21] Possible problems include:

- Damage to brain: encephalitis,[26] microcephaly, hydrocephaly,[27] aplasia of brain

- Damage to the eye: optic stalk, optic cup, and lens vesicles, microphthalmia, cataracts, chorioretinitis, optic atrophy

- Other neurological disorder: damage to cervical and lumbosacral spinal cord, motor/sensory deficits, absent deep tendon reflexes, anisocoria/Horner’s syndrome

- Damage to body: hypoplasia of upper/lower extremities, anal and bladder sphincter dysfunction

- Skin disorders: (cicatricial) skin lesions, hypopigmentation

Infection late in gestation or immediately following birth is referred to as «neonatal varicella«.[28] Maternal infection is associated with premature delivery. The risk of the baby developing the disease is greatest following exposure to infection in the period 7 days before delivery and up to 8 days following the birth. The baby may also be exposed to the virus via infectious siblings or other contacts, but this is of less concern if the mother is immune. Newborns who develop symptoms are at a high risk of pneumonia and other serious complications of the disease.[29]

Pathophysiology[edit]

Exposure to VZV in a healthy child initiates the production of host immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin M (IgM), and immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies; IgG antibodies persist for life and confer immunity. Cell-mediated immune responses are also important in limiting the scope and the duration of primary varicella infection. After primary infection, VZV is hypothesized to spread from mucosal and epidermal lesions to local sensory nerves. VZV then remains latent in the dorsal ganglion cells of the sensory nerves. Reactivation of VZV results in the clinically distinct syndrome of herpes zoster (i.e., shingles), postherpetic neuralgia,[30] and sometimes Ramsay Hunt syndrome type II.[31] Varicella zoster can affect the arteries in the neck and head, producing stroke, either during childhood, or after a latency period of many years.[32]

Shingles[edit]

After a chickenpox infection, the virus remains dormant in the body’s nerve tissues for about 50 years. This, however, does not mean that VZV cannot be contracted later in life. The immune system usually keeps the virus at bay, however it can still manifest itself at any given age between 1 and 60, causing a different form of the viral infection called shingles (also known as herpes zoster).[33] Since the human immune system efficacy decreases with age, the United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) suggests that every adult over the age of 50 years get the herpes zoster vaccine.[34]

Shingles affects one in five adults infected with chickenpox as children, especially those who are immune-suppressed, particularly from cancer, HIV, or other conditions. Stress can bring on shingles as well, although scientists are still researching the connection.[35] Adults over the age of 60 who had chickenpox but not shingles are the most prone age demographic.[36]

Diagnosis[edit]

The diagnosis of chickenpox is primarily based on the signs and symptoms, with typical early symptoms followed by a characteristic rash. Confirmation of the diagnosis is by examination of the fluid within the vesicles of the rash, or by testing blood for evidence of an acute immunologic response.[37]

Vesicular fluid can be examined with a Tzanck smear, or by testing for direct fluorescent antibody. The fluid can also be «cultured», whereby attempts are made to grow the virus from a fluid sample. Blood tests can be used to identify a response to acute infection (IgM) or previous infection and subsequent immunity (IgG).[38]

Prenatal diagnosis of fetal varicella infection can be performed using ultrasound, though a delay of 5 weeks following primary maternal infection is advised. A PCR (DNA) test of the mother’s amniotic fluid can also be performed, though the risk of spontaneous abortion due to the amniocentesis procedure is higher than the risk of the baby’s developing fetal varicella syndrome.[29]

Prevention[edit]

Hygiene measures[edit]

The spread of chickenpox can be prevented by isolating affected individuals. Contagion is by exposure to respiratory droplets, or direct contact with lesions, within a period lasting from three days before the onset of the rash, to four days after the onset of the rash.[39] The chickenpox virus is susceptible to disinfectants, notably chlorine bleach (i.e., sodium hypochlorite). Like all enveloped viruses, it is sensitive to drying, heat and detergents.[21]

Vaccine[edit]

Chickenpox can be prevented by vaccination.[2] The side effects are usually mild, such as some pain or swelling at the injection site.[2]

A live attenuated varicella vaccine, the Oka strain, was developed by Michiaki Takahashi and his colleagues in Japan in the early 1970s.[40] In 1981, Merck & Co. licensed the «Oka» strain of the varicella virus in the United States, and Maurice Hilleman’s team at Merck invented a varicella vaccine in the same year.[41][42][43]

The varicella vaccine is recommended in many countries.[11] Some countries require the varicella vaccination or an exemption before entering elementary school. A second dose is recommended five years after the initial immunization.[44] A vaccinated person is likely to have a milder case of chickenpox if they become infected.[45] Immunization within three days following household contact reduces infection rates and severity in children.[12] Being exposed to chickenpox as an adult (for example, through contact with infected children) may boost immunity to shingles. So it was thought, that when the majority of children are vaccinated against chickenpox, adults might lose this natural boosting, so immunity would drop and more shingles cases would occur.[46] On the other hand, current observations suggest that exposure to children with varicella is not a critical factor in the maintenance of immunity. Multiple subclinical reactivations of varicella zoster virus may occur spontaneously and, despite not causing clinical disease, may still provide an endogenous boost to immunity against zoster.[47]

It is part of the routine immunization schedule in the US.[48] Some European countries include it as part of universal vaccinations in children,[49] but not all countries provide the vaccine.[11] In the UK as of 2014, the vaccine is only recommended in people who are particularly vulnerable to chickenpox. This is to keep the virus in circulation thereby exposing the population to the virus at an early age, when it is less harmful, and to reduce the occurrence of shingles in those who have already had chickenpox by repeated exposure to the virus later in life.[50] In populations that have not been immunized or if immunity is questionable, a clinician may order an enzyme immunoassay. An immunoassay measures the levels of antibodies against the virus that give immunity to a person. If the levels of antibodies are low (low titer) or questionable, reimmunization may be done.[51]

Treatment[edit]

Treatment mainly consists of easing the symptoms. As a protective measure, people are usually required to stay at home while they are infectious to avoid spreading the disease to others. Cutting the fingernails short or wearing gloves may prevent scratching and minimize the risk of secondary infections.[52]

Although there have been no formal clinical studies evaluating the effectiveness of topical application of calamine lotion (a topical barrier preparation containing zinc oxide, and one of the most commonly used interventions), it has an excellent safety profile.[53] Maintaining good hygiene and daily cleaning of skin with warm water can help to avoid secondary bacterial infection;[54] scratching may increase the risk of secondary infection.[55]

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) but not aspirin may be used to reduce fever. Aspirin use by someone with chickenpox may cause serious, sometimes fatal disease of the liver and brain, Reye syndrome. People at risk of developing severe complications who have had significant exposure to the virus may be given intra-muscular varicella zoster immune globulin (VZIG), a preparation containing high titres of antibodies to varicella zoster virus, to ward off the disease.[56][57]

Antivirals are sometimes used.[58][59]

Children[edit]

If aciclovir by mouth is started within 24 hours of rash onset, it decreases symptoms by one day but has no effect on complication rates.[60][61] Use of aciclovir therefore is not currently recommended for individuals with normal immune function. Children younger than 12 years old and older than one month are not meant to receive antiviral drugs unless they have another medical condition which puts them at risk of developing complications.[62]

Treatment of chickenpox in children is aimed at symptoms while the immune system deals with the virus. With children younger than 12 years, cutting fingernails and keeping them clean is an important part of treatment as they are more likely to scratch their blisters more deeply than adults.[63]

Aspirin is highly contraindicated in children younger than 16 years, as it has been related to Reye syndrome.[64]

Adults[edit]

Infection in otherwise healthy adults tends to be more severe.[65] Treatment with antiviral drugs (e.g. aciclovir or valaciclovir) is generally advised, as long as it is started within 24–48 hours from rash onset.[62] Remedies to ease the symptoms of chickenpox in adults are basically the same as those used for children. Adults are more often prescribed antiviral medication, as it is effective in reducing the severity of the condition and the likelihood of developing complications. Adults are advised to increase water intake to reduce dehydration and to relieve headaches. Painkillers such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) are recommended, as they are effective in relieving itching and other symptoms such as fever or pains. Antihistamines relieve itching and may be used in cases where the itching prevents sleep, because they also act as a sedative. As with children, antiviral medication is considered more useful for those adults who are more prone to develop complications. These include pregnant women or people who have a weakened immune system.[66]

Prognosis[edit]

The duration of the visible blistering caused by varicella zoster virus varies in children usually from 4 to 7 days, and the appearance of new blisters begins to subside after the fifth day. Chickenpox infection is milder in young children, and symptomatic treatment, with sodium bicarbonate baths or antihistamine medication may ease itching.

In adults, the disease is more severe,[67] though the incidence is much less common. Infection in adults is associated with greater morbidity and mortality due to pneumonia (either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia),[68] bronchitis (either viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis),[68] hepatitis,[69] and encephalitis.[70] In particular, up to 10% of pregnant women with chickenpox develop pneumonia, the severity of which increases with onset later in gestation. In England and Wales, 75% of deaths due to chickenpox are in adults.[29] Inflammation of the brain, encephalitis, can occur in immunocompromised individuals, although the risk is higher with herpes zoster.[71] Necrotizing fasciitis is also a rare complication.[72]

Varicella can be lethal to individuals with impaired immunity. The number of people in this high-risk group has increased, due to the HIV epidemic and the increased use of immunosuppressive therapies.[73] Varicella is a particular problem in hospitals when there are patients with immune systems weakened by drugs (e.g., high-dose steroids) or HIV.[74]

Secondary bacterial infection of skin lesions, manifesting as impetigo, cellulitis, and erysipelas, is the most common complication in healthy children. Disseminated primary varicella infection usually seen in the immunocompromised may have high morbidity. Ninety percent of cases of varicella pneumonia occur in the adult population. Rarer complications of disseminated chickenpox include myocarditis, hepatitis, and glomerulonephritis.[75]

Hemorrhagic complications are more common in the immunocompromised or immunosuppressed populations, although healthy children and adults have been affected. Five major clinical syndromes have been described: febrile purpura, malignant chickenpox with purpura, postinfectious purpura, purpura fulminans, and anaphylactoid purpura. These syndromes have variable courses, with febrile purpura being the most benign of the syndromes and having an uncomplicated outcome. In contrast, malignant chickenpox with purpura is a grave clinical condition that has a mortality rate of greater than 70%. The cause of these hemorrhagic chickenpox syndromes is not known.[75]

Epidemiology[edit]

Primary varicella occurs in all countries worldwide. In 2015 chickenpox resulted in 6,400 deaths globally – down from 8,900 in 1990.[6] There were 7,000 deaths in 2013.[14] Varicella is highly transmissible, with an infection rate of 90% in close contacts.[76]

In temperate countries, chickenpox is primarily a disease of children, with most cases occurring during the winter and spring, most likely due to school contact. In such countries it is one of the classic diseases of childhood, with most cases occurring in children up to age 15;[77] most people become infected before adulthood, and 10% of young adults remain susceptible.

In the United States, a temperate country, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) do not require state health departments to report infections of chickenpox, and only 31 states volunteered this information as of 2013.[78] A 2013 study conducted by the social media disease surveillance tool called Sickweather used anecdotal reports of chickenpox infections on social media systems Facebook and Twitter to measure and rank states with the most infections per capita, with Maryland, Tennessee and Illinois in the top three.[79]

In the tropics, chickenpox often occurs in older people and may cause more serious disease.[80] In adults, the pock marks are darker and the scars more prominent than in children.[81]

Society and culture[edit]

Etymology[edit]

How the term chickenpox originated is not clear but it may be due to it being a relatively mild disease.[15] It has been said to be derived from chickpeas, based on resemblance of the vesicles to chickpeas,[15][82][83] or to come from the rash resembling chicken pecks.[83] Other suggestions include the designation chicken for a child (i.e., literally ‘child pox’), a corruption of itching-pox,[82][84] or the idea that the disease may have originated in chickens.[85] Samuel Johnson explained the designation as «from its being of no very great danger».[86]

Intentional exposure[edit]

Because chickenpox is usually more severe in adults than it is in children, some parents deliberately expose their children to the virus, for example by taking them to «chickenpox parties».[87] Doctors say that children are safer getting the vaccine, which is a weakened form of the virus, than getting the disease, which can be fatal or lead to shingles later in life.[87][88][89] Repeated exposure to chickenpox may protect against zoster.[90]

Other animals[edit]

Humans are the only known species that the disease affects naturally.[8] However, chickenpox has been caused in other primates, including chimpanzees[91] and gorillas.[92]

Research[edit]

Sorivudine, a nucleoside analog, has been reported to be effective in the treatment of primary varicella in healthy adults (case reports only), but large-scale clinical trials are still needed to demonstrate its efficacy.[93] There was speculation in 2005 that continuous dosing of aciclovir by mouth for a period of time could eradicate VZV from the host, although further trials were required to discern whether eradication was actually viable.[94]

See also[edit]

- Measles

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f «Chickenpox (Varicella) Signs & Symptoms». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov). 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d «Chickenpox (Varicella) For Healthcare Professionals». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov). 31 December 2018. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ a b «Chickenpox (Varicella) Overview». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov). 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ a b «Routine vaccination against chickenpox?». Drug Ther Bull. 50 (4): 42–45. 2012. doi:10.1136/dtb.2012.04.0098. PMID 22495050. S2CID 42875272.

- ^ a b c d e f g h «Chickenpox (Varicella) Prevention & Treatment». cdc.gov. 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ a b c GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. (8 October 2016). «Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015». Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ «Chickenpox (Varicella) Complications». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov). 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Atkinson, William (2011). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (12 ed.). Public Health Foundation. pp. 301–323. ISBN 978-0983263135. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ «Chickenpox (Varicella) Interpreting Laboratory Tests». cdc.gov. 19 June 2012. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ Breuer J (2010). «VZV molecular epidemiology». Varicella-zoster Virus. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 342. pp. 15–42. doi:10.1007/82_2010_9. ISBN 978-3-642-12727-4. PMID 20229231.

- ^ a b c Flatt, A; Breuer, J (September 2012). «Varicella vaccines». British Medical Bulletin. 103 (1): 115–127. doi:10.1093/bmb/lds019. PMID 22859715.

- ^ a b Macartney, K; Heywood, A; McIntyre, P (23 June 2014). «Vaccines for post-exposure prophylaxis against varicella (chickenpox) in children and adults». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD001833. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001833.pub3. PMC 7061782. PMID 24954057. S2CID 43465932.

- ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators (22 August 2015). «Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013». Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- ^ a b GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (17 December 2014). «Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013». Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ a b c d Oxford University Press (December 2014). «chickenpox, n.» oed.com. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ «Chickenpox». Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ a b Anthony J Papadopoulos. Dirk M Elston (ed.). «Chickenpox Clinical Presentation». Medscape Reference. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ «Symptoms of Chickenpox». Chickenpox. NHS Choices. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ «Chickenpox (Varicella): Clinical Overview». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 April 2019. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017.

- ^ «Chickenpox (varicella)». Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d «Chickenpox — Symptoms and causes». Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Askalan R, Laughlin S, Mayank S, Chan A, MacGregor D, Andrew M, Curtis R, Meaney B, deVeber G (June 2001). «Chickenpox and stroke in childhood: a study of frequency and causation». Stroke. 32 (6): 1257–1262. doi:10.1161/01.STR.32.6.1257. PMID 11387484.

- ^ Heuchan AM, Isaacs D (19 March 2001). «The management of varicella-zoster virus exposure and infection in pregnancy and the newborn period. Australasian Subgroup in Paediatric Infectious Diseases of the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases». The Medical Journal of Australia. 174 (6): 288–292. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143273.x. PMID 11297117. S2CID 37646516. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013.

- ^ Brannon, Heather (22 July 2007). «Chickenpox in Pregnanc». Dermatology. About.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Boussault P, Boralevi F, Labbe L, Sarlangue J, Taïeb A, Leaute-Labreze C (2007). «Chronic varicella-zoster skin infection complicating the congenital varicella syndrome». Pediatr Dermatol. 24 (4): 429–432. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00471.x. PMID 17845179. S2CID 22389596.

- ^ Matsuo T, Koyama M, Matsuo N (July 1990). «Acute retinal necrosis as a novel complication of chickenpox in adults». Br J Ophthalmol. 74 (7): 443–444. doi:10.1136/bjo.74.7.443. PMC 1042160. PMID 2378860.

- ^ Mazzella M, Arioni C, Bellini C, Allegri AE, Savioli C, Serra G (2003). «Severe hydrocephalus associated with congenital varicella syndrome». Canadian Medical Association Journal. 168 (5): 561–563. PMC 149248. PMID 12615748.

- ^ Sauerbrei A, Wutzler P (December 2001). «Neonatal varicella». J Perinatol. 21 (8): 545–549. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7210599. PMID 11774017.

- ^ a b c Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (September 2007). «Chickenpox in Pregnancy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Kanbayashi Y, Onishi K, Fukazawa K, Okamoto K, Ueno H, Takagi T, Hosokawa T (2012). «Predictive Factors for Postherpetic Neuralgia Using Ordered Logistic Regression Analysis». The Clinical Journal of Pain. 28 (8): 712–714. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e318243ee01. PMID 22209800. S2CID 11980597.

- ^ Pino Rivero V, González Palomino A, Pantoja Hernández CG, Mora Santos ME, Trinidad Ramos G, Blasco Huelva A (2006). «Ramsay-Hunt syndrome associated to unilateral recurrential paralysis». Anales Otorrinolaringologicos Ibero-americanos. 33 (5): 489–494. PMID 17091862.

- ^ Nagel MA, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Wellish MC, Forghani B, Schiller A, Safdieh JE, Kamenkovich E, Ostrow LW, Levy M, Greenberg B, Russman AN, Katzan I, Gardner CJ, Häusler M, Nau R, Saraya T, Wada H, Goto H, de Martino M, Ueno M, Brown WD, Terborg C, Gilden DH (March 2008). «The varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: clinical, CSF, imaging, and virologic features». Neurology. 70 (11): 853–860. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000304747.38502.e8. PMC 2938740. PMID 18332343.

- ^ «Chickenpox». NHS Choices. UK Department of Health. 19 April 2012. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009.

- ^ «Shingles Vaccine». WebMD. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013.

- ^ «An Overview of Shingles». WebMD. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013.

- ^ «Shingles». PubMed Health.

- ^ Ayoade, Folusakin; Kumar, Sandeep (2020), «Varicella Zoster (Chickenpox)», StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28846365, retrieved 21 October 2020

- ^ Pincus, Matthew R.; McPherson, Richard A.; Henry, John Bernard (2007). «Ch. 54». Henry’s clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods (21st ed.). Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-0287-1.

- ^ Murray, Patrick R.; Rosenthal, Ken S.; Pfaller, Michael A. (2005). Medical Microbiology (5th ed.). Elsevier Mosby. p. 551. ISBN 978-0-323-03303-9., edition (Elsevier), p.

- ^ Gershon, Anne A. (2007), Arvin, Ann; Campadelli-Fiume, Gabriella; Mocarski, Edward; Moore, Patrick S. (eds.), «Varicella-zoster vaccine», Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82714-0, PMID 21348127, retrieved 6 February 2021

- ^ Tulchinsky, Theodore H. (2018). «Maurice Hilleman: Creator of Vaccines That Changed the World». Case Studies in Public Health: 443–470. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804571-8.00003-2. ISBN 9780128045718. PMC 7150172.

- ^ «Chickenpox (Varicella) | History of Vaccines». www.historyofvaccines.org. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ «Maurice Ralph Hilleman (1919–2005) | The Embryo Project Encyclopedia». embryo.asu.edu. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ Chaves SS, Gargiullo P, Zhang JX, Civen R, Guris D, Mascola L, Seward JF (2007). «Loss of vaccine-induced immunity to varicella over time». N Engl J Med. 356 (11): 1121–1129. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa064040. PMID 17360990.

- ^ «Chickenpox (varicella) vaccination». NHS Choices. UK Department of Health. 19 April 2012. Archived from the original on 13 July 2010.

- ^ «Chickenpox vaccine FAQs». 23 January 2019.

- ^ «Live Attenuated Varicella Vaccine: Prevention of Varicella and of Zoster». 30 September 2021.

- ^ «Child, Adolescent & «Catch-up» Immunization Schedules». Immunization Schedules. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 March 2019. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016.

- ^ Carrillo-Santisteve, P; Lopalco, PL (May 2014). «Varicella vaccination: a laboured take-off». Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 Suppl 5: 86–91. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12580. PMID 24494784.

- ^ «Why aren’t children in the UK vaccinated against chickenpox?». NHS. UK National Health Service. 26 June 2018. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Leeuwen, Anne (2015). Davis’s comprehensive handbook of laboratory & diagnostic tests with nursing implications. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company. p. 1579. ISBN 978-0803644052.

- ^ CDC (28 April 2021). «Chickenpox Prevention and Treatment». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Tebruegge M, Kuruvilla M, Margarson I (2006). «Does the use of calamine or antihistamine provide symptomatic relief from pruritus in children with varicella zoster infection?». Arch. Dis. Child. 91 (12): 1035–1036. doi:10.1136/adc.2006.105114. PMC 2082986. PMID 17119083.

- ^ Domino, Frank J. (2007). The 5-Minute Clinical Consult. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-7817-6334-9.

- ^ Brannon, Heather (21 May 2008). Chicken Pox Treatments Archived 26 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. About.com.

- ^ Parmet S, Lynm C, Glass RM (February 2004). «JAMA patient page. Chickenpox». JAMA. 291 (7): 906. doi:10.1001/jama.291.7.906. PMID 14970070.

- ^ Naus M; et al. (15 October 2006). «Varizig™ as the Varicella Zoster Immune Globulin for the Prevention of Varicella in At-Risk Patients». Canada Communicable Disease Report. 32 (ACS-8). Archived from the original on 17 January 2013.

- ^ Huff JC (January 1988). «Antiviral treatment in chickenpox and herpes zoster». Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 18 (1 Pt 2): 204–206. doi:10.1016/S0190-9622(88)70029-8. PMID 3339143.

- ^ Gnann, John W. Jr. (2007). «Chapter 65Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections». In Arvin, Ann; et al. (eds.). Human herpesviruses : biology, therapy, and immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82714-0. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- ^ Kay, A. B. (2001). «Allergy and allergic diseases. First of two parts». The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (1): 30–37. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101043440106. PMID 11136958.

- ^ Kay, A. B. (2001). «Allergy and allergic diseases. Second of two parts». The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (2): 109–113. doi:10.1056/NEJM200101113440206. PMID 11150362.

- ^ a b «Antiviral medications for chickenpox». Archived from the original on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ «Chickenpox in Children Under 12». Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ «Reye’s Syndrome-Topic Overview». Archived from the original on 5 April 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Tunbridge AJ, Breuer J, Jeffery KJ (August 2008). «Chickenpox in adults – clinical management». The Journal of Infection. 57 (2): 95–102. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2008.03.004. PMID 18555533.

- ^ «What is chickenpox?». Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ Baren JM, Henneman PL, Lewis RJ (August 1996). «Primary Varicella in Adults: Pneumonia, Pregnancy, and Hospital Admissions». Annals of Emergency Medicine. 28 (2): 165–169. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(96)70057-4. PMID 8759580.

- ^ a b Mohsen AH, McKendrick M (May 2003). «Varicella pneumonia in adults». Eur. Respir. J. 21 (5): 886–891. doi:10.1183/09031936.03.00103202. PMID 12765439.

- ^ Anderson, D.R.; Schwartz, J.; Hunter, N.J.; Cottrill, C.; Bissaccia, E.; Klainer, A.S. (1994). «Varicella Hepatitis: A Fatal Case in a Previously Healthy, Immunocompetent Adult». Archives of Internal Medicine. 154 (18): 2101–2106. doi:10.1001/archinte.1994.00420180111013. PMID 8092915.

- ^ Abro AH, Ustadi AM, Das K, Abdou AM, Hussaini HS, Chandra FS (December 2009). «Chickenpox: presentation and complications in adults». Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 59 (12): 828–831. PMID 20201174. Archived from the original on 20 May 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ^ «Definition of Chickenpox». MedicineNet.com. Archived from the original on 28 July 2006. Retrieved 18 August 2006.

- ^ «Is Necrotizing Fasciitis a complication of Chickenpox of Cutaneous Vasculitis?». atmedstu.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2008. Retrieved 18 January 2008.

- ^ Strangfeld A, Listing J, Herzer P, Liebhaber A, Rockwitz K, Richter C, Zink A (February 2009). «Risk of herpes zoster in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with anti-TNF-alpha agents». JAMA. 301 (7): 737–744. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.146. PMID 19224750.

- ^ Weller TH (1997). «Varicella-herpes zoster virus». In Evans AS, Kaslow RA (eds.). Viral Infections of Humans: Epidemiology and Control. Plenum Press. pp. 865–892. ISBN 978-0-306-44855-3.

- ^ a b Chicken Pox Complications Archived 28 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ CDC (11 August 2021). «Chickenpox for HCPs». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Di Pietrantonj, Carlo; Rivetti, Alessandro; Marchione, Pasquale; Debalini, Maria Grazia; Demicheli, Vittorio (22 November 2021). «Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (11): CD004407. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004407.pub5. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8607336. PMID 34806766.

- ^ «Georgia ranks 10th for social media admissions of chickenpox». Archived from the original on 21 June 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ «Chickenpox in the USA». Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ^ Wharton M (1996). «The epidemiology of varicella-zoster virus infections». Infect Dis Clin North Am. 10 (3): 571–581. doi:10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70313-5. PMID 8856352.

- ^ «Epidemiology of Varicella Zoster Virus Infection, Epidemiology of VZV Infection, Epidemiology of Chicken Pox, Epidemiology of Shingles». Archived from the original on 13 June 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ^ a b Belshe, Robert B. (1984). Textbook of human virology (2nd ed.). Littleton, MA: PSG. p. 829. ISBN 978-0-88416-458-6.

- ^ a b Teri Shors (2011). «Herpesviruses: Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV)». Understanding Viruses (2nd ed.). Jones & Bartlett. p. 459. ISBN 978-0-7637-8553-6.

- ^ Pattison, John; Zuckerman, Arie J.; Banatvala, J.E. (1994). Principles and practice of clinical virology (3rd ed.). Wiley. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-471-93106-5.

- ^ Chicken-pox is recorded in Oxford English Dictionary 2nd ed. since 1684; the OED records several suggested etymologies

- ^ Johnson, Samuel (1839). Dictionary of the English language. London: Williamson. p. 195.

- ^ a b Charles, M.D., Shamard (22 March 2019). «Doctors say Kentucky Gov. Matt Bevin is wrong about ‘chickenpox on purpose’«. NBC News. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

Chickenpox parties were once a popular way for parents to expose their children to the virus so they would get sick, recover and build up immunity to the disease. … Most doctors believe that deliberately infecting a child with the full-blown virus is a bad idea. While chickenpox is mild for most children, it can be a dangerous virus for others – and there’s no way to know which child will have a serious case, experts say.

- ^ «Chicken Pox parties do more harm than good, says doctor». KSLA News 12 Shreveport, Louisiana News Weather & Sports. Archived from the original on 27 January 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2011.

- ^ Committee to Review Adverse Effects of Vaccines; Institute of, Medicine; Stratton, K.; Ford, A.; Rusch, E.; Clayton, E. W. (2011). Adverse Effects of Vaccines: Evidence and Causality. doi:10.17226/13164. ISBN 978-0-309-21435-3. PMID 24624471. S2CID 67935593.

- ^ Ogunjimi, B; Van Damme, P; Beutels, P (2013). «Herpes Zoster Risk Reduction through Exposure to Chickenpox Patients: A Systematic Multidisciplinary Review». PLOS ONE. 8 (6): e66485. Bibcode:2013PLoSO…866485O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066485. PMC 3689818. PMID 23805224.

- ^ Cohen JI, Moskal T, Shapiro M, Purcell RH (December 1996). «Varicella in Chimpanzees». Journal of Medical Virology. 50 (4): 289–292. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199612)50:4<289::AID-JMV2>3.0.CO;2-4. PMID 8950684. S2CID 28842789.

- ^ Myers MG, Kramer LW, Stanberry LR (December 1987). «Varicella in a gorilla». Journal of Medical Virology. 23 (4): 317–322. doi:10.1002/jmv.1890230403. PMID 2826674. S2CID 84875752.

- ^ «Chickenpox Treatment & Management: Approach Considerations, Treatment in Healthy Children, Treatment in Immunocompetent Adults». Medscape emedicine. 3 June 2022.

- ^ Klassen, TP; Hartling, L. (2005). «Acyclovir for treating varicella in otherwise healthy children and adolescents». Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2011 (4): CD002980. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD002980.pub3. PMC 8407192. PMID 16235308. S2CID 11018303.

External links[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chickenpox.

- Chickenpox at Curlie

- Prevention of Varicella: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 1996

- Antiviral therapy of varicella-zoster virus infections, 2007

- Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases: Varicella, US CDC’s «Pink Book»

- Chickenpox at MedlinePlus

| Chickenpox | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Varicella |

|

|

| A boy presenting with the characteristic blisters of chickenpox | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Small, itchy blisters, headache, loss of appetite, tiredness, fever[1] |

| Usual onset | 10–21 days after exposure[2] |

| Duration | 5–10 days[1] |

| Causes | Varicella zoster virus[3] |

| Prevention | Varicella vaccine[4] |

| Medication | Calamine lotion, paracetamol (acetaminophen), aciclovir[5] |

| Deaths | 6,400 per year (with shingles)[6] |

Chickenpox, also known as varicella, is a highly contagious disease caused by the initial infection with varicella zoster virus (VZV).[3] The disease results in a characteristic skin rash that forms small, itchy blisters, which eventually scab over.[1] It usually starts on the chest, back, and face.[1] It then spreads to the rest of the body.[1] The rash and other symptoms, such as fever, tiredness, and headaches, usually last five to seven days.[1] Complications may occasionally include pneumonia, inflammation of the brain, and bacterial skin infections.[7] The disease is usually more severe in adults than in children.[8]

Chickenpox is an airborne disease which spreads easily from one person to the next through the coughs and sneezes of an infected person.[5] The incubation period is 10–21 days, after which the characteristic rash appears.[2] It may be spread from one to two days before the rash appears until all lesions have crusted over.[5] It may also spread through contact with the blisters.[5] Those with shingles may spread chickenpox to those who are not immune through contact with the blisters.[5] The disease can usually be diagnosed based on the presenting symptom;[9] however, in unusual cases it may be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of the blister fluid or scabs.[8] Testing for antibodies may be done to determine if a person is immune.[8] People usually only get chickenpox once.[5] Although reinfections by the virus occur, these reinfections usually do not cause any symptoms.[10]

Since its introduction in 1995, the varicella vaccine has resulted in a decrease in the number of cases and complications from the disease.[4] It protects about 70–90 percent of people from disease with a greater benefit for severe disease.[8] Routine immunization of children is recommended in many countries.[11] Immunization within three days of exposure may improve outcomes in children.[12] Treatment of those infected may include calamine lotion to help with itching, keeping the fingernails short to decrease injury from scratching, and the use of paracetamol (acetaminophen) to help with fevers.[5] For those at increased risk of complications, antiviral medication such as aciclovir are recommended.[5]

Chickenpox occurs in all parts of the world.[8] In 2013 there were 140 million cases of chickenpox and shingles worldwide.[13] Before routine immunization the number of cases occurring each year was similar to the number of people born.[8] Since immunization the number of infections in the United States has decreased nearly 90%.[8] In 2015 chickenpox resulted in 6,400 deaths globally – down from 8,900 in 1990.[6][14] Death occurs in about 1 per 60,000 cases.[8] Chickenpox was not separated from smallpox until the late 19th century.[8] In 1888 its connection to shingles was determined.[8] The first documented use of the term chicken pox was in 1658.[15] Various explanations have been suggested for the use of «chicken» in the name, one being the relative mildness of the disease.[15]

Signs and symptoms[edit]

A single blister, typical during the early stages of the rash

The early (prodromal) symptoms in adolescents and adults are nausea, loss of appetite, aching muscles, and headache.[16] This is followed by the characteristic rash or oral sores, malaise, and a low-grade fever that signal the presence of the disease. Oral manifestations of the disease (enanthem) not uncommonly may precede the external rash (exanthem). In children the illness is not usually preceded by prodromal symptoms, and the first sign is the rash or the spots in the oral cavity. The rash begins as small red dots on the face, scalp, torso, upper arms and legs; progressing over 10–12 hours to small bumps, blisters and pustules; followed by umbilication and the formation of scabs.[17][18]

At the blister stage, intense itching is usually present. Blisters may also occur on the palms, soles, and genital area. Commonly, visible evidence of the disease develops in the oral cavity and tonsil areas in the form of small ulcers which can be painful or itchy or both; this enanthem (internal rash) can precede the exanthem (external rash) by 1 to 3 days or can be concurrent. These symptoms of chickenpox appear 10 to 21 days after exposure to a contagious person. Adults may have a more widespread rash and longer fever, and they are more likely to experience complications, such as varicella pneumonia.[17]

Because watery nasal discharge containing live virus usually precedes both exanthem (external rash) and enanthem (oral ulcers) by 1 to 2 days, the infected person actually becomes contagious one to two days before recognition of the disease. Contagiousness persists until all vesicular lesions have become dry crusts (scabs), which usually entails four or five days, by which time nasal shedding of live virus ceases.[19] The condition usually resolves by itself within a week or two.[20] The rash may, however, last for up to one month.[medical citation needed][21]

Chickenpox is rarely fatal, although it is generally more severe in adult men than in women or children. Non-immune pregnant women and those with a suppressed immune system are at highest risk of serious complications. Arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) associated with chickenpox in the previous year accounts for nearly one third of childhood AIS.[22] The most common late complication of chickenpox is shingles (herpes zoster), caused by reactivation of the varicella zoster virus decades after the initial, often childhood, chickenpox infection.[21]

-

The back of a 30-year-old male after five days of the rash

-

A 3-year-old girl with a chickenpox rash on her torso

-

Lower leg of a child with chickenpox

-

A child with chickenpox

-

A child with chickenpox on her face.

-

A child with chickenpox

-

Chickenpox blister closeup, day 7 after start of fever

Pregnancy and neonates[edit]

During pregnancy the dangers to the fetus associated with a primary VZV infection are greater in the first six months. In the third trimester, the mother is more likely to have severe symptoms.[23]

For pregnant women, antibodies produced as a result of immunization or previous infection are transferred via the placenta to the fetus.[24]

Varicella infection in pregnant women could lead to spread via the placenta and infection of the fetus. If infection occurs during the first 28 weeks of gestation, this can lead to fetal varicella syndrome (also known as congenital varicella syndrome).[25] Effects on the fetus can range in severity from underdeveloped toes and fingers to severe anal and bladder malformation.[21] Possible problems include:

- Damage to brain: encephalitis,[26] microcephaly, hydrocephaly,[27] aplasia of brain

- Damage to the eye: optic stalk, optic cup, and lens vesicles, microphthalmia, cataracts, chorioretinitis, optic atrophy

- Other neurological disorder: damage to cervical and lumbosacral spinal cord, motor/sensory deficits, absent deep tendon reflexes, anisocoria/Horner’s syndrome

- Damage to body: hypoplasia of upper/lower extremities, anal and bladder sphincter dysfunction

- Skin disorders: (cicatricial) skin lesions, hypopigmentation

Infection late in gestation or immediately following birth is referred to as «neonatal varicella«.[28] Maternal infection is associated with premature delivery. The risk of the baby developing the disease is greatest following exposure to infection in the period 7 days before delivery and up to 8 days following the birth. The baby may also be exposed to the virus via infectious siblings or other contacts, but this is of less concern if the mother is immune. Newborns who develop symptoms are at a high risk of pneumonia and other serious complications of the disease.[29]

Pathophysiology[edit]

Exposure to VZV in a healthy child initiates the production of host immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin M (IgM), and immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies; IgG antibodies persist for life and confer immunity. Cell-mediated immune responses are also important in limiting the scope and the duration of primary varicella infection. After primary infection, VZV is hypothesized to spread from mucosal and epidermal lesions to local sensory nerves. VZV then remains latent in the dorsal ganglion cells of the sensory nerves. Reactivation of VZV results in the clinically distinct syndrome of herpes zoster (i.e., shingles), postherpetic neuralgia,[30] and sometimes Ramsay Hunt syndrome type II.[31] Varicella zoster can affect the arteries in the neck and head, producing stroke, either during childhood, or after a latency period of many years.[32]

Shingles[edit]

After a chickenpox infection, the virus remains dormant in the body’s nerve tissues for about 50 years. This, however, does not mean that VZV cannot be contracted later in life. The immune system usually keeps the virus at bay, however it can still manifest itself at any given age between 1 and 60, causing a different form of the viral infection called shingles (also known as herpes zoster).[33] Since the human immune system efficacy decreases with age, the United States Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) suggests that every adult over the age of 50 years get the herpes zoster vaccine.[34]

Shingles affects one in five adults infected with chickenpox as children, especially those who are immune-suppressed, particularly from cancer, HIV, or other conditions. Stress can bring on shingles as well, although scientists are still researching the connection.[35] Adults over the age of 60 who had chickenpox but not shingles are the most prone age demographic.[36]

Diagnosis[edit]

The diagnosis of chickenpox is primarily based on the signs and symptoms, with typical early symptoms followed by a characteristic rash. Confirmation of the diagnosis is by examination of the fluid within the vesicles of the rash, or by testing blood for evidence of an acute immunologic response.[37]

Vesicular fluid can be examined with a Tzanck smear, or by testing for direct fluorescent antibody. The fluid can also be «cultured», whereby attempts are made to grow the virus from a fluid sample. Blood tests can be used to identify a response to acute infection (IgM) or previous infection and subsequent immunity (IgG).[38]

Prenatal diagnosis of fetal varicella infection can be performed using ultrasound, though a delay of 5 weeks following primary maternal infection is advised. A PCR (DNA) test of the mother’s amniotic fluid can also be performed, though the risk of spontaneous abortion due to the amniocentesis procedure is higher than the risk of the baby’s developing fetal varicella syndrome.[29]

Prevention[edit]

Hygiene measures[edit]

The spread of chickenpox can be prevented by isolating affected individuals. Contagion is by exposure to respiratory droplets, or direct contact with lesions, within a period lasting from three days before the onset of the rash, to four days after the onset of the rash.[39] The chickenpox virus is susceptible to disinfectants, notably chlorine bleach (i.e., sodium hypochlorite). Like all enveloped viruses, it is sensitive to drying, heat and detergents.[21]

Vaccine[edit]

Chickenpox can be prevented by vaccination.[2] The side effects are usually mild, such as some pain or swelling at the injection site.[2]

A live attenuated varicella vaccine, the Oka strain, was developed by Michiaki Takahashi and his colleagues in Japan in the early 1970s.[40] In 1981, Merck & Co. licensed the «Oka» strain of the varicella virus in the United States, and Maurice Hilleman’s team at Merck invented a varicella vaccine in the same year.[41][42][43]

The varicella vaccine is recommended in many countries.[11] Some countries require the varicella vaccination or an exemption before entering elementary school. A second dose is recommended five years after the initial immunization.[44] A vaccinated person is likely to have a milder case of chickenpox if they become infected.[45] Immunization within three days following household contact reduces infection rates and severity in children.[12] Being exposed to chickenpox as an adult (for example, through contact with infected children) may boost immunity to shingles. So it was thought, that when the majority of children are vaccinated against chickenpox, adults might lose this natural boosting, so immunity would drop and more shingles cases would occur.[46] On the other hand, current observations suggest that exposure to children with varicella is not a critical factor in the maintenance of immunity. Multiple subclinical reactivations of varicella zoster virus may occur spontaneously and, despite not causing clinical disease, may still provide an endogenous boost to immunity against zoster.[47]

It is part of the routine immunization schedule in the US.[48] Some European countries include it as part of universal vaccinations in children,[49] but not all countries provide the vaccine.[11] In the UK as of 2014, the vaccine is only recommended in people who are particularly vulnerable to chickenpox. This is to keep the virus in circulation thereby exposing the population to the virus at an early age, when it is less harmful, and to reduce the occurrence of shingles in those who have already had chickenpox by repeated exposure to the virus later in life.[50] In populations that have not been immunized or if immunity is questionable, a clinician may order an enzyme immunoassay. An immunoassay measures the levels of antibodies against the virus that give immunity to a person. If the levels of antibodies are low (low titer) or questionable, reimmunization may be done.[51]

Treatment[edit]

Treatment mainly consists of easing the symptoms. As a protective measure, people are usually required to stay at home while they are infectious to avoid spreading the disease to others. Cutting the fingernails short or wearing gloves may prevent scratching and minimize the risk of secondary infections.[52]

Although there have been no formal clinical studies evaluating the effectiveness of topical application of calamine lotion (a topical barrier preparation containing zinc oxide, and one of the most commonly used interventions), it has an excellent safety profile.[53] Maintaining good hygiene and daily cleaning of skin with warm water can help to avoid secondary bacterial infection;[54] scratching may increase the risk of secondary infection.[55]

Paracetamol (acetaminophen) but not aspirin may be used to reduce fever. Aspirin use by someone with chickenpox may cause serious, sometimes fatal disease of the liver and brain, Reye syndrome. People at risk of developing severe complications who have had significant exposure to the virus may be given intra-muscular varicella zoster immune globulin (VZIG), a preparation containing high titres of antibodies to varicella zoster virus, to ward off the disease.[56][57]

Antivirals are sometimes used.[58][59]

Children[edit]

If aciclovir by mouth is started within 24 hours of rash onset, it decreases symptoms by one day but has no effect on complication rates.[60][61] Use of aciclovir therefore is not currently recommended for individuals with normal immune function. Children younger than 12 years old and older than one month are not meant to receive antiviral drugs unless they have another medical condition which puts them at risk of developing complications.[62]

Treatment of chickenpox in children is aimed at symptoms while the immune system deals with the virus. With children younger than 12 years, cutting fingernails and keeping them clean is an important part of treatment as they are more likely to scratch their blisters more deeply than adults.[63]

Aspirin is highly contraindicated in children younger than 16 years, as it has been related to Reye syndrome.[64]

Adults[edit]

Infection in otherwise healthy adults tends to be more severe.[65] Treatment with antiviral drugs (e.g. aciclovir or valaciclovir) is generally advised, as long as it is started within 24–48 hours from rash onset.[62] Remedies to ease the symptoms of chickenpox in adults are basically the same as those used for children. Adults are more often prescribed antiviral medication, as it is effective in reducing the severity of the condition and the likelihood of developing complications. Adults are advised to increase water intake to reduce dehydration and to relieve headaches. Painkillers such as paracetamol (acetaminophen) are recommended, as they are effective in relieving itching and other symptoms such as fever or pains. Antihistamines relieve itching and may be used in cases where the itching prevents sleep, because they also act as a sedative. As with children, antiviral medication is considered more useful for those adults who are more prone to develop complications. These include pregnant women or people who have a weakened immune system.[66]

Prognosis[edit]

The duration of the visible blistering caused by varicella zoster virus varies in children usually from 4 to 7 days, and the appearance of new blisters begins to subside after the fifth day. Chickenpox infection is milder in young children, and symptomatic treatment, with sodium bicarbonate baths or antihistamine medication may ease itching.

In adults, the disease is more severe,[67] though the incidence is much less common. Infection in adults is associated with greater morbidity and mortality due to pneumonia (either direct viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia),[68] bronchitis (either viral bronchitis or secondary bacterial bronchitis),[68] hepatitis,[69] and encephalitis.[70] In particular, up to 10% of pregnant women with chickenpox develop pneumonia, the severity of which increases with onset later in gestation. In England and Wales, 75% of deaths due to chickenpox are in adults.[29] Inflammation of the brain, encephalitis, can occur in immunocompromised individuals, although the risk is higher with herpes zoster.[71] Necrotizing fasciitis is also a rare complication.[72]

Varicella can be lethal to individuals with impaired immunity. The number of people in this high-risk group has increased, due to the HIV epidemic and the increased use of immunosuppressive therapies.[73] Varicella is a particular problem in hospitals when there are patients with immune systems weakened by drugs (e.g., high-dose steroids) or HIV.[74]

Secondary bacterial infection of skin lesions, manifesting as impetigo, cellulitis, and erysipelas, is the most common complication in healthy children. Disseminated primary varicella infection usually seen in the immunocompromised may have high morbidity. Ninety percent of cases of varicella pneumonia occur in the adult population. Rarer complications of disseminated chickenpox include myocarditis, hepatitis, and glomerulonephritis.[75]

Hemorrhagic complications are more common in the immunocompromised or immunosuppressed populations, although healthy children and adults have been affected. Five major clinical syndromes have been described: febrile purpura, malignant chickenpox with purpura, postinfectious purpura, purpura fulminans, and anaphylactoid purpura. These syndromes have variable courses, with febrile purpura being the most benign of the syndromes and having an uncomplicated outcome. In contrast, malignant chickenpox with purpura is a grave clinical condition that has a mortality rate of greater than 70%. The cause of these hemorrhagic chickenpox syndromes is not known.[75]

Epidemiology[edit]

Primary varicella occurs in all countries worldwide. In 2015 chickenpox resulted in 6,400 deaths globally – down from 8,900 in 1990.[6] There were 7,000 deaths in 2013.[14] Varicella is highly transmissible, with an infection rate of 90% in close contacts.[76]

In temperate countries, chickenpox is primarily a disease of children, with most cases occurring during the winter and spring, most likely due to school contact. In such countries it is one of the classic diseases of childhood, with most cases occurring in children up to age 15;[77] most people become infected before adulthood, and 10% of young adults remain susceptible.

In the United States, a temperate country, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) do not require state health departments to report infections of chickenpox, and only 31 states volunteered this information as of 2013.[78] A 2013 study conducted by the social media disease surveillance tool called Sickweather used anecdotal reports of chickenpox infections on social media systems Facebook and Twitter to measure and rank states with the most infections per capita, with Maryland, Tennessee and Illinois in the top three.[79]

In the tropics, chickenpox often occurs in older people and may cause more serious disease.[80] In adults, the pock marks are darker and the scars more prominent than in children.[81]

Society and culture[edit]

Etymology[edit]

How the term chickenpox originated is not clear but it may be due to it being a relatively mild disease.[15] It has been said to be derived from chickpeas, based on resemblance of the vesicles to chickpeas,[15][82][83] or to come from the rash resembling chicken pecks.[83] Other suggestions include the designation chicken for a child (i.e., literally ‘child pox’), a corruption of itching-pox,[82][84] or the idea that the disease may have originated in chickens.[85] Samuel Johnson explained the designation as «from its being of no very great danger».[86]

Intentional exposure[edit]

Because chickenpox is usually more severe in adults than it is in children, some parents deliberately expose their children to the virus, for example by taking them to «chickenpox parties».[87] Doctors say that children are safer getting the vaccine, which is a weakened form of the virus, than getting the disease, which can be fatal or lead to shingles later in life.[87][88][89] Repeated exposure to chickenpox may protect against zoster.[90]

Other animals[edit]

Humans are the only known species that the disease affects naturally.[8] However, chickenpox has been caused in other primates, including chimpanzees[91] and gorillas.[92]

Research[edit]

Sorivudine, a nucleoside analog, has been reported to be effective in the treatment of primary varicella in healthy adults (case reports only), but large-scale clinical trials are still needed to demonstrate its efficacy.[93] There was speculation in 2005 that continuous dosing of aciclovir by mouth for a period of time could eradicate VZV from the host, although further trials were required to discern whether eradication was actually viable.[94]

See also[edit]

- Measles

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f «Chickenpox (Varicella) Signs & Symptoms». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov). 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d «Chickenpox (Varicella) For Healthcare Professionals». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov). 31 December 2018. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ^ a b «Chickenpox (Varicella) Overview». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov). 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ a b «Routine vaccination against chickenpox?». Drug Ther Bull. 50 (4): 42–45. 2012. doi:10.1136/dtb.2012.04.0098. PMID 22495050. S2CID 42875272.

- ^ a b c d e f g h «Chickenpox (Varicella) Prevention & Treatment». cdc.gov. 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ a b c GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. (8 October 2016). «Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015». Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ «Chickenpox (Varicella) Complications». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cdc.gov). 16 November 2011. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Atkinson, William (2011). Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases (12 ed.). Public Health Foundation. pp. 301–323. ISBN 978-0983263135. Archived from the original on 7 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ «Chickenpox (Varicella) Interpreting Laboratory Tests». cdc.gov. 19 June 2012. Archived from the original on 4 February 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ Breuer J (2010). «VZV molecular epidemiology». Varicella-zoster Virus. Current Topics in Microbiology and Immunology. Vol. 342. pp. 15–42. doi:10.1007/82_2010_9. ISBN 978-3-642-12727-4. PMID 20229231.

- ^ a b c Flatt, A; Breuer, J (September 2012). «Varicella vaccines». British Medical Bulletin. 103 (1): 115–127. doi:10.1093/bmb/lds019. PMID 22859715.

- ^ a b Macartney, K; Heywood, A; McIntyre, P (23 June 2014). «Vaccines for post-exposure prophylaxis against varicella (chickenpox) in children and adults». The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD001833. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001833.pub3. PMC 7061782. PMID 24954057. S2CID 43465932.

- ^ Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators (22 August 2015). «Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013». Lancet. 386 (9995): 743–800. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(15)60692-4. PMC 4561509. PMID 26063472.

- ^ a b GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (17 December 2014). «Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013». Lancet. 385 (9963): 117–171. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMC 4340604. PMID 25530442.

- ^ a b c d Oxford University Press (December 2014). «chickenpox, n.» oed.com. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ «Chickenpox». Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ a b Anthony J Papadopoulos. Dirk M Elston (ed.). «Chickenpox Clinical Presentation». Medscape Reference. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ^ «Symptoms of Chickenpox». Chickenpox. NHS Choices. Archived from the original on 18 March 2013. Retrieved 14 March 2013.

- ^ «Chickenpox (Varicella): Clinical Overview». Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 22 April 2019. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017.

- ^ «Chickenpox (varicella)». Archived from the original on 5 December 2010. Retrieved 6 November 2010.

- ^ a b c d «Chickenpox — Symptoms and causes». Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ Askalan R, Laughlin S, Mayank S, Chan A, MacGregor D, Andrew M, Curtis R, Meaney B, deVeber G (June 2001). «Chickenpox and stroke in childhood: a study of frequency and causation». Stroke. 32 (6): 1257–1262. doi:10.1161/01.STR.32.6.1257. PMID 11387484.

- ^ Heuchan AM, Isaacs D (19 March 2001). «The management of varicella-zoster virus exposure and infection in pregnancy and the newborn period. Australasian Subgroup in Paediatric Infectious Diseases of the Australasian Society for Infectious Diseases». The Medical Journal of Australia. 174 (6): 288–292. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143273.x. PMID 11297117. S2CID 37646516. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013.

- ^ Brannon, Heather (22 July 2007). «Chickenpox in Pregnanc». Dermatology. About.com. Archived from the original on 27 July 2009. Retrieved 20 June 2009.

- ^ Boussault P, Boralevi F, Labbe L, Sarlangue J, Taïeb A, Leaute-Labreze C (2007). «Chronic varicella-zoster skin infection complicating the congenital varicella syndrome». Pediatr Dermatol. 24 (4): 429–432. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.2007.00471.x. PMID 17845179. S2CID 22389596.

- ^ Matsuo T, Koyama M, Matsuo N (July 1990). «Acute retinal necrosis as a novel complication of chickenpox in adults». Br J Ophthalmol. 74 (7): 443–444. doi:10.1136/bjo.74.7.443. PMC 1042160. PMID 2378860.

- ^ Mazzella M, Arioni C, Bellini C, Allegri AE, Savioli C, Serra G (2003). «Severe hydrocephalus associated with congenital varicella syndrome». Canadian Medical Association Journal. 168 (5): 561–563. PMC 149248. PMID 12615748.

- ^ Sauerbrei A, Wutzler P (December 2001). «Neonatal varicella». J Perinatol. 21 (8): 545–549. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7210599. PMID 11774017.

- ^ a b c Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (September 2007). «Chickenpox in Pregnancy» (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

- ^ Kanbayashi Y, Onishi K, Fukazawa K, Okamoto K, Ueno H, Takagi T, Hosokawa T (2012). «Predictive Factors for Postherpetic Neuralgia Using Ordered Logistic Regression Analysis». The Clinical Journal of Pain. 28 (8): 712–714. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e318243ee01. PMID 22209800. S2CID 11980597.

- ^ Pino Rivero V, González Palomino A, Pantoja Hernández CG, Mora Santos ME, Trinidad Ramos G, Blasco Huelva A (2006). «Ramsay-Hunt syndrome associated to unilateral recurrential paralysis». Anales Otorrinolaringologicos Ibero-americanos. 33 (5): 489–494. PMID 17091862.

- ^ Nagel MA, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Wellish MC, Forghani B, Schiller A, Safdieh JE, Kamenkovich E, Ostrow LW, Levy M, Greenberg B, Russman AN, Katzan I, Gardner CJ, Häusler M, Nau R, Saraya T, Wada H, Goto H, de Martino M, Ueno M, Brown WD, Terborg C, Gilden DH (March 2008). «The varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: clinical, CSF, imaging, and virologic features». Neurology. 70 (11): 853–860. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000304747.38502.e8. PMC 2938740. PMID 18332343.

- ^ «Chickenpox». NHS Choices. UK Department of Health. 19 April 2012. Archived from the original on 24 November 2009.

- ^ «Shingles Vaccine». WebMD. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013.

- ^ «An Overview of Shingles». WebMD. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013.

- ^ «Shingles». PubMed Health.

- ^ Ayoade, Folusakin; Kumar, Sandeep (2020), «Varicella Zoster (Chickenpox)», StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28846365, retrieved 21 October 2020

- ^ Pincus, Matthew R.; McPherson, Richard A.; Henry, John Bernard (2007). «Ch. 54». Henry’s clinical diagnosis and management by laboratory methods (21st ed.). Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-0287-1.