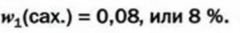

| Вода | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Систематическое наименование |

Оксид водорода Вода |

| Традиционные названия | вода |

| Хим. формула | H2O |

| Состояние | жидкость |

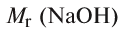

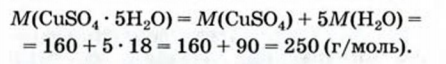

| Молярная масса | 18,01528 г/моль |

| Плотность | 0,9982 г/см3 |

| Твёрдость | 1,5 |

| Динамическая вязкость | 0,00101 Па·с |

| Кинематическая вязкость | 0,01012 см²/с (при 20 °C) |

| Скорость звука в веществе | (дистиллированная вода) 1348 м/с |

| Т. плав. | 273,1 K (0 ° C) |

| Т. кип. | 373,1 K (99,974 ° C) °C |

| Тройная точка | 273,2 K (0,01 ° C), 611,72 Па |

| Кр. точка | 647,1 K (374 ° C), 22,064 МПа |

| Мол. теплоёмк. | 75,37 Дж/(моль·К) |

| Теплопроводность | 0,56 Вт/(м·K) |

| Удельная теплота испарения | 2256,2 кДж/кг |

| Удельная теплота плавления | 332,4 кДж/кг |

| Показатель преломления | 1,3945, 1,33432, 1,32612, 1,39336, 1,33298 и 1,32524 |

| Рег. номер CAS | 7732-18-5 |

| PubChem | 962 |

| Рег. номер EINECS | 231-791-2 |

| SMILES |

O |

| InChI |

1S/H2O/h1H2 XLYOFNOQVPJJNP-UHFFFAOYSA-N |

| RTECS | ZC0110000 |

| ChEBI | 15377 |

| ChemSpider | 937 |

| Приводятся данные для стандартных условий (25 °C, 100 кПа), если не указано иного. |

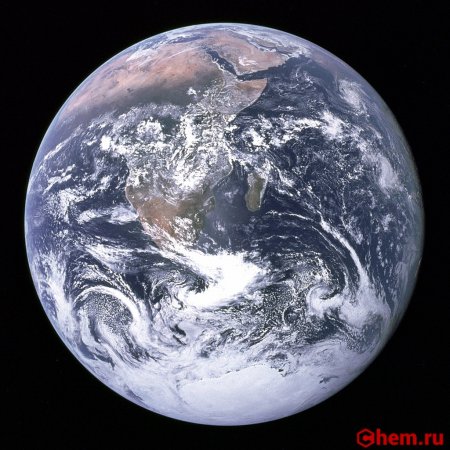

(71% воды и 29% суши, но назвали планета Земля, а не планета Вода….)

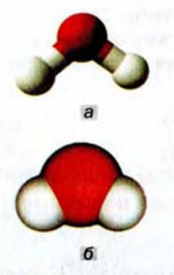

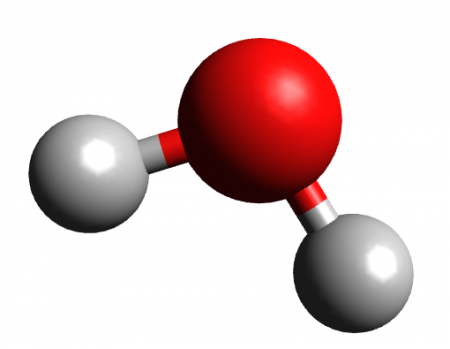

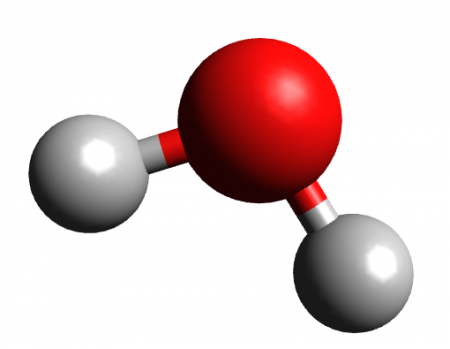

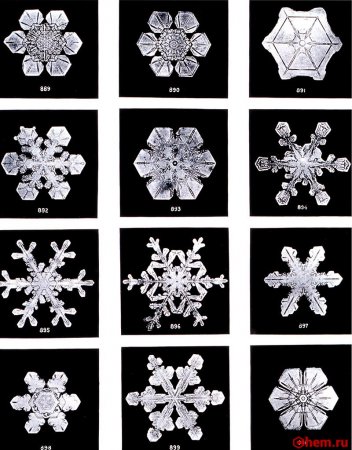

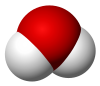

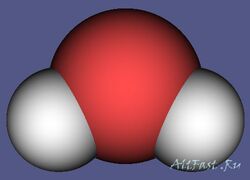

Вода (оксид водорода) — бинарное неорганическое соединение с химической формулой H2O: молекула воды состоит из двух атомов водорода и одного — кислорода, которые соединены между собой ковалентной связью. При нормальных условиях представляет собой прозрачную жидкость, не имеющую цвета (при малой толщине слоя), запаха и вкуса. В твёрдом состоянии называется льдом (кристаллы льда могут образовывать снег или иней), а в газообразном — водяным паром. Вода также может существовать в виде жидких кристаллов (на гидрофильных поверхностях).

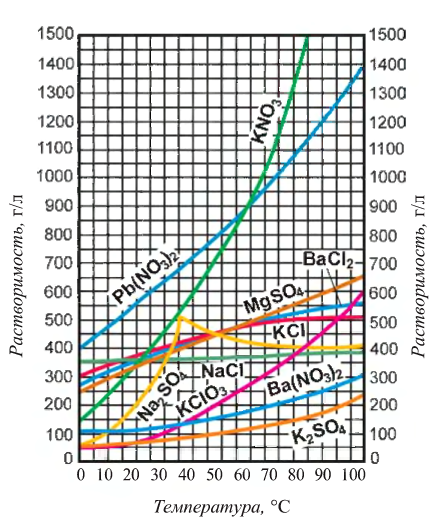

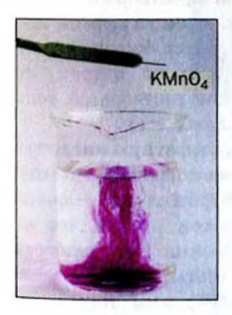

Вода является хорошим сильнополярным растворителем. В природных условиях всегда содержит растворённые вещества (соли, газы).

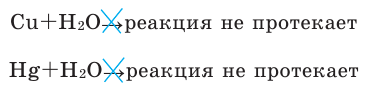

Исключительно важна роль воды в глобальном кругообороте вещества и энергии, возникновении и поддержании жизни на Земле, в химическом строении живых организмов, в формировании климата и погоды. Вода является важнейшим веществом для всех живых существ на Земле.

Всего на Земле около 1400 млн кубических километров воды. Вода покрывает 71 % поверхности земного шара (океаны, моря, озёра, реки, льды — 361,13 млн квадратных километров). Бо́льшая часть земной воды (97,54 %) принадлежит Мировому океану — это солёная вода, непригодная для сельского хозяйства и питья. Пресная же вода находится в основном в ледниках (1,81 %) и подземных водах (около 0,63 %), и лишь небольшая часть (0,009 %) в реках и озерах. Материковые солёные воды составляют 0,007 %, в атмосфере содержится 0,001 % от всей воды нашей планеты.

Содержание

- 1 Химические названия

- 2 Образование воды

- 3 Свойства

- 3.1 Физические свойства

- 3.1.1 Агрегатные состояния

- 3.2 Оптические свойства

- 3.3 Изотопные модификации

- 3.4 Химические свойства

- 3.4.1 Волновая функция основного состояния воды

- 3.1 Физические свойства

- 4 Виды

- 5 В природе

- 5.1 Атмосферные осадки

- 5.2 Вода за пределами Земли

- 6 Биологическая роль

- 7 Применение

- 8 Исследования

- 8.1 Происхождение воды на планете

- 8.2 Гидрология

- 8.3 Гидрогеология

- 9 Факты

Химические названия

С формальной точки зрения вода имеет несколько различных корректных химических названий:

- Оксид водорода: бинарное соединение водорода с атомом кислорода в степени окисления −2, встречается также устаревшее название окись водорода.

- Гидроксид водорода: соединение гидроксильной группы OH— и катиона (H+)

- Гидроксильная кислота: воду можно рассматривать как соединение катиона H+, который может быть замещён металлом, и «гидроксильного остатка» OH—

- Монооксид дигидрогена

- Дигидромонооксид

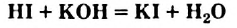

Образование воды

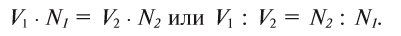

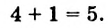

Известно, что 2 объема водорода взаимодействуют с 1 объемом кислорода с образованием воды. При реакции выделяется большое количество тепла, как и при горении свечи. Продукт реакции — вода — не похожа на исходные вещества — водород и кислород. Следовательно, превращение, происходящее при взаимодействии водорода и кислорода, должно быть отнесено к химическим реакциям.

В соответствии с атомно-молекулярной теорией мы начинаем рассуждение, предполагая, что в реакции участвуют молекулы H2 и O2. В результате реакции образуются молекулы воды. Связи между атомами в реагирующих веществах разрываются и атомы перегруппировываются. При этом возникают новые связи в молекулах продукта реакции. Эти превращения легко представить с помощью молекулярных моделей. Молекулярную модель можно представить как две молекулы H2 (четыре атома) и одна молекула O2 (два атома). Если эти молекулы будут реагировать с образованием воды, то связи между атомами в молекулах водорода и кислорода должны разорваться. Затем «завязываются» новые связи и образуются две молекулы воды. Отметим, что в результате реакции происходит перегруппировка атомов, но общее число атомов при этом не изменяется.

Пример образования молекул воды

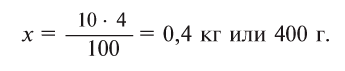

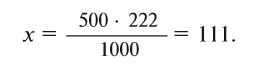

Один миллион молекул кислорода реагирует с достаточно большим количеством молекул водорода с образованием воды. Сколько молекул воды образуется? Сколько молекул водорода требуется для этой реакции?

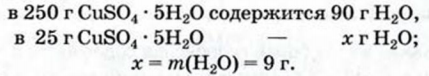

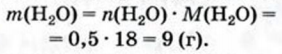

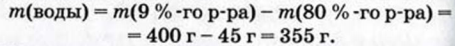

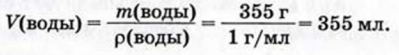

Для получения 100 молекул воды расходуется 100 молекул водорода и 50 молекул кислорода. Таким образом, для получения 1 моля воды (6,02 · 1023 молекул) нам потребуется 1 моль водорода (6,02 · 1023 молекул) и 0,5 моля кислорода (3,01 · 1023 молекул). Результаты приведены в таблице:

| Водород | Кислород | Вода | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Число молекул | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 4 | 2 | 4 | |

| 100 | 50 | 100 | |

| 6,02 · 1023 | 3,01 · 1023 | 6,02 · 1023 | |

| Число молей | 1 | 0,5 | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| 10 | 5 | 10 |

Реакция между водородом и кислородом протекает намного быстрее, если эти газы смешать и затем поджечь смесь искрой. Происходит сильный взрыв. Тем не менее, на 1 моль реагирующего водорода образуется такое же количество продукта реакции — воды — и выделяется столько же тепла, как и при обычном горении.

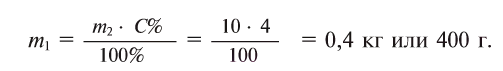

Если реагируют 1 моль чистого водорода и 0,5 моля чистого кислорода, образуется 1 моль воды. Количество тепла, выделяющееся при образовании 1 моля воды, равно 68000 кал. Если же мы возьмем только 0,025 моля чистого водорода, то потребуется 0,5 · 0,025 моля кислорода. При этом образуется 0,025 моля воды. Если получено только 0,025 моля воды, то выделяется лишь 0,025 · 68 000 = 1700 кал тепла.

Источником этой тепловой энергии должны быть сами реагирующие вещества (водород и кислород), так как к системе извне подводится только тепло, необходимое для поджигания смеси. Отсюда можно сделать вывод, что вода содержит меньше энергии, чем реагирующие вещества, используемые для ее получения. Реакция, при которой выделяется тепло, называется экзотермической. Количество тепла, выделяющееся при сгорании 1 моля водорода (68 000 кал, или 68 ккал), называется молярной теплотой сгорания водорода.

Свойства

Физические свойства

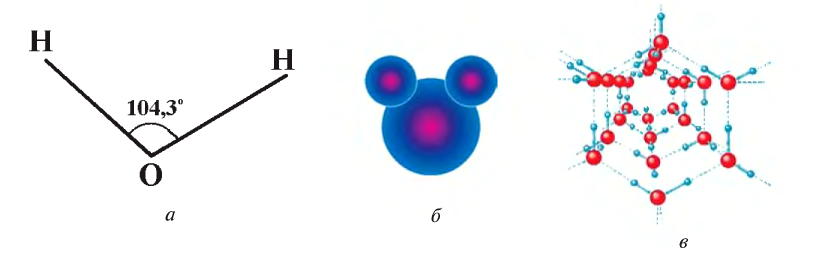

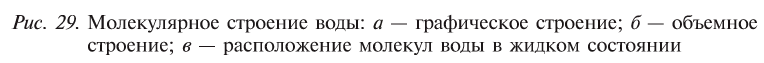

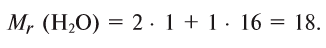

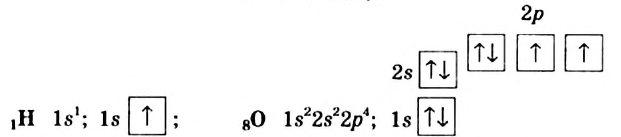

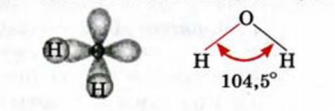

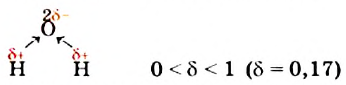

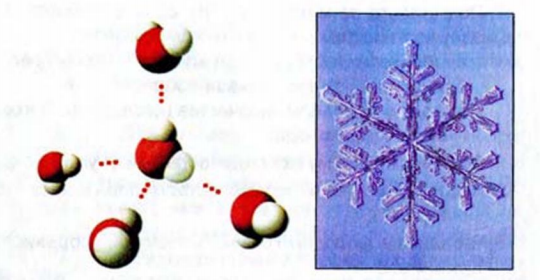

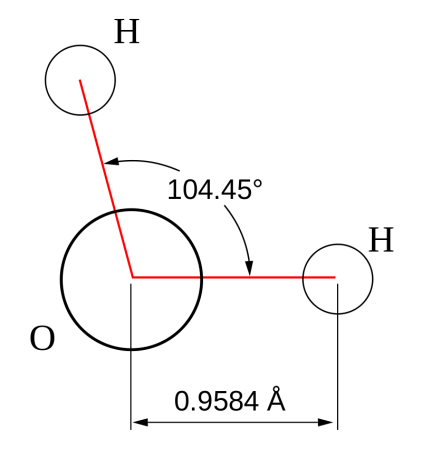

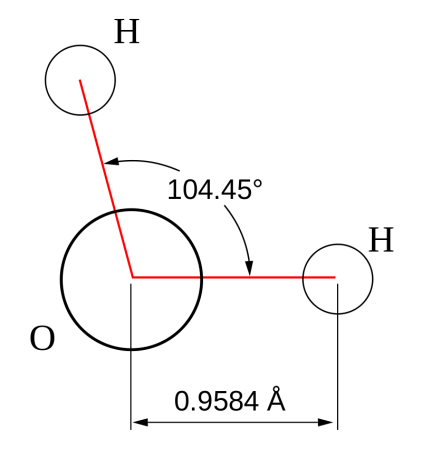

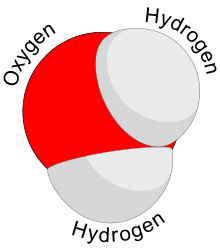

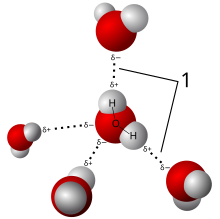

Вода при нормальных условиях находится в жидком состоянии, тогда как аналогичные водородные соединения других элементов являются газами (H2S, CH4, HF). Атомы водорода присоединены к атому кислорода, образуя угол 104,45° (104°27′). Из-за большой разности электроотрицательностей атомов водорода и кислорода электронные облака сильно смещены в сторону кислорода. По этой причине молекула воды обладает большим дипольным моментом (p = 1,84 Д, уступает только синильной кислоте). Каждая молекула воды образует до четырёх водородных связей — две из них образует атом кислорода и две — атомы водорода. Количество водородных связей и их разветвлённая структура определяют высокую температуру кипения воды и её удельную теплоту парообразования. Если бы не было водородных связей, вода, на основании места кислорода в таблице Менделеева и температур кипения гидридов аналогичных кислороду элементов (серы, селена, теллура), кипела бы при −80 °С, а замерзала при −100 °С.

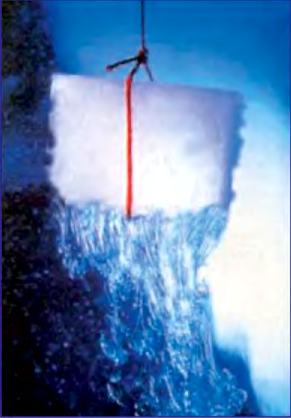

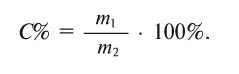

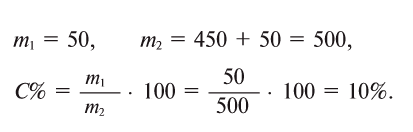

При переходе в твёрдое состояние молекулы воды упорядочиваются, при этом объёмы пустот между молекулами увеличиваются, и общая плотность воды падает, что и объясняет меньшую плотность (больший объём) воды в фазе льда. При испарении, напротив, все водородные связи рвутся. Разрыв связей требует много энергии, отчего у воды самая большая удельная теплоёмкость среди прочих жидкостей и твёрдых веществ. Для того чтобы нагреть один литр воды на один градус, требуется затратить 4,1868 кДж энергии. Благодаря этому свойству вода нередко используется как теплоноситель. Помимо большой удельной теплоёмкости, вода также имеет большие значения удельной теплоты плавления (333,55 кДж/кг при 0 °C) и парообразования (2250 кДж/кг).

| Температура, °С | Удельная теплоёмкость воды, кДж/(кг*К) |

|---|---|

| -60 (лёд) | 1,64 |

| -20 (лёд) | 2,01 |

| -10 (лёд) | 2,22 |

| 0 (лёд) | 2,11 |

| 0 (чистая вода) | 4,218 |

| 10 | 4,192 |

| 20 | 4,182 |

| 40 | 4,178 |

| 60 | 4,184 |

| 80 | 4,196 |

| 100 | 4,216 |

Физические свойства разных изотопных модификаций воды при различных температурах:

| Модификация воды | Максимальная плотность при температуре, °С | Тройная точка при температуре, °С |

|---|---|---|

| H2O | 3,9834 | 0,01 |

| D2O | 11,2 | 3,82 |

| T2O | 13,4 | 4,49 |

| H218O | 4,3 | 0,31 |

Вода обладает также высоким поверхностным натяжением, уступая в этом только ртути. Относительно высокая вязкость воды обусловлена тем, что водородные связи мешают молекулам воды двигаться с разными скоростями.

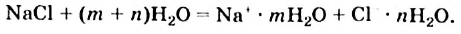

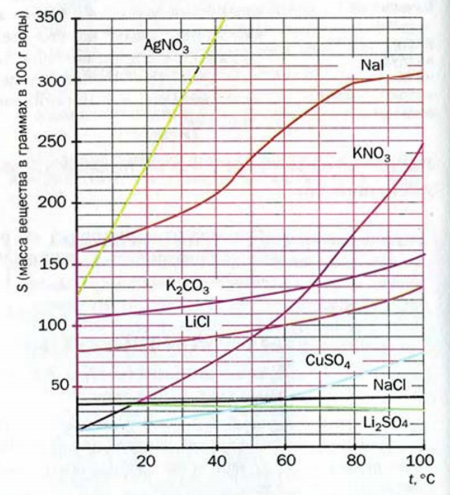

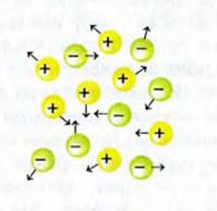

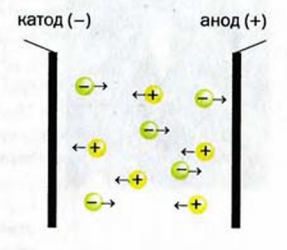

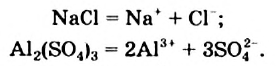

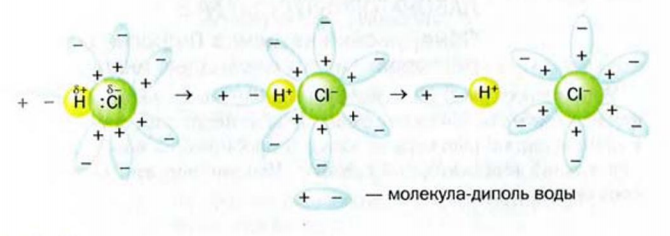

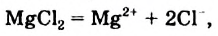

Вода является хорошим растворителем полярных веществ. Каждая молекула растворяемого вещества окружается молекулами воды, причём положительно заряженные участки молекулы растворяемого вещества притягивают атомы кислорода, а отрицательно заряженные — атомы водорода. Поскольку молекула воды мала по размерам, много молекул воды могут окружить каждую молекулу растворяемого вещества.

Это свойство воды используется живыми существами. В живой клетке и в межклеточном пространстве вступают во взаимодействие растворы различных веществ в воде. Вода необходима для жизни всех без исключения одноклеточных и многоклеточных живых существ на Земле.

Вода обладает отрицательным электрическим потенциалом поверхности.

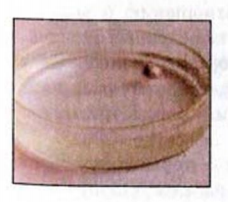

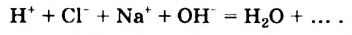

Капля, ударяющаяся о поверхность воды

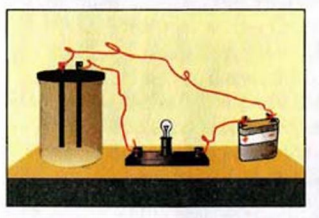

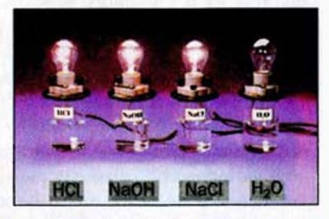

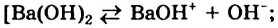

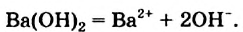

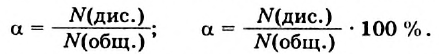

Чистая вода — хороший изолятор. При нормальных условиях вода слабо диссоциирована и концентрация протонов (точнее, ионов гидроксония H3O+) и гидроксильных ионов OH− составляет 10-7 моль/л. Но поскольку вода — хороший растворитель, в ней практически всегда растворены те или иные соли, то есть присутствуют другие положительные и отрицательные ионы. Благодаря этому вода проводит электричество. По электропроводности воды можно определить её чистоту.

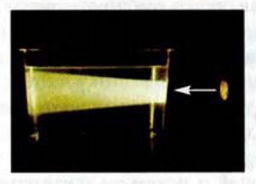

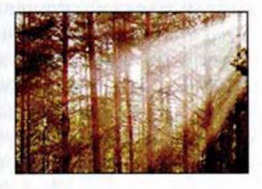

Вода имеет показатель преломления n=1,33 в оптическом диапазоне. Однако она сильно поглощает инфракрасное излучение, и поэтому водяной пар является основным естественным парниковым газом, отвечающим более чем за 60 % парникового эффекта. Благодаря большому дипольному моменту молекул, вода также поглощает микроволновое излучение, на чём основан принцип действия микроволновой печи.

Агрегатные состояния

Фазовая диаграмма воды: по вертикальной оси — давление в Па, по горизонтальной — температура в Кельвинах. Отмечены критическая (647,3 K; 22,1 МПа) и тройная (273,16 K; 610 Па) точки. Римскими цифрами отмечены различные структурные модификации льда

Основные статьи: Водяной пар, Лёд, Фазовая диаграмма воды

По состоянию различают:

- «Твёрдое» — лёд

- «Жидкое» — вода

- «Газообразное» — водяной пар

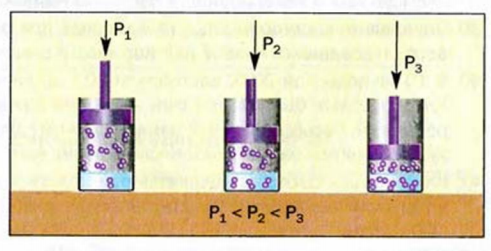

При нормальном атмосферном давлении (760 мм рт. ст., 101 325 Па) вода переходит в твёрдое состояние при температуре в 0 °C и кипит (превращается в водяной пар) при температуре 100 °C (значения 0 °C и 100 °C были выбраны как соответствующие температурам таяния льда и кипения воды при создании температурной шкалы «по Цельсию»). При снижении давления температура таяния (плавления) льда медленно растёт, а температура кипения воды — падает. При давлении в 611,73 Па (около 0,006 атм) температура кипения и плавления совпадает и становится равной 0,01 °C. Такие давление и температура называются тройной точкой воды. При более низком давлении вода не может находиться в жидком состоянии, и лёд превращается непосредственно в пар. Температура возгонки (сублимации) льда падает со снижением давления. При высоком давлении существуют модификации льда с температурами плавления выше комнатной.

С ростом давления температура кипения воды растёт:

| Давление, атм. | Температура кипения (Ткип), °C |

|---|---|

| 0,987 (105 Па — нормальные условия) | 99,63 |

| 1 | 100 |

| 2 | 120 |

| 6 | 158 |

| 218,5 | 374,1 |

При росте давления плотность насыщенного водяного пара в точке кипения тоже растёт, а жидкой воды — падает. При температуре 374 °C (647 K) и давлении 22,064 МПа (218 атм) вода проходит критическую точку. В этой точке плотность и другие свойства жидкой и газообразной воды совпадают. При более высоком давлении и/или температуре исчезает разница между жидкой водой и водяным паром. Такое агрегатное состояние называют «сверхкритическая жидкость».

Вода может находиться в метастабильных состояниях — пересыщенный пар, перегретая жидкость, переохлаждённая жидкость. Эти состояния могут существовать длительное время, однако они неустойчивы и при соприкосновении с более устойчивой фазой происходит переход. Например, можно получить переохлаждённую жидкость, охладив чистую воду в чистом сосуде ниже 0 °C, однако при появлении центра кристаллизации жидкая вода быстро превращается в лёд.

Оптические свойства

Они оцениваются по прозрачности воды, которая, в свою очередь, зависит от длины волны излучения, проходящего через воду. Вследствие поглощения оранжевых и красных компонентов света вода приобретает голубоватую окраску. Вода прозрачна только для видимого света и сильно поглощает инфракрасное излучение, поэтому на инфракрасных фотографиях водная поверхность всегда получается чёрной. Ультрафиолетовые лучи легко проходят через воду, поэтому растительные организмы способны развиваться в толще воды и на дне водоёмов, инфракрасные лучи проникают только в поверхностный слой. Вода отражает 5 % солнечных лучей, в то время как снег — около 85 %. Под лёд океана проникает только 2 % солнечного света.

Изотопные модификации

Основная статья: Изотопный состав воды

И кислород, и водород имеют природные и искусственные изотопы. В зависимости от типа изотопов водорода, входящих в молекулу, выделяют следующие виды воды:

- лёгкая вода (основная составляющая привычной людям воды) H2O

- тяжёлая вода (дейтериевая) D2O

- сверхтяжёлая вода (тритиевая) T2O

- тритий-дейтериевая вода TDO

- тритий-протиевая вода THO

- дейтерий-протиевая вода DHO

Последние три вида возможны, так как молекула воды содержит два атома водорода. Протий — самый лёгкий изотоп водорода, дейтерий имеет атомную массу 2,0141017778 а. е. м., тритий — самый тяжёлый, атомная масса 3,0160492777 а. е. м. В воде из-под крана тяжелокислородной воды (H2O17 и H2O18) содержится больше, чем воды D2O16: их содержание, соответственно, 1,8 кг и 0,15 кг на тонну.

Хотя тяжёлая вода часто считается мёртвой водой, так как живые организмы в ней жить не могут, некоторые микроорганизмы могут быть приучены к существованию в ней.

По стабильным изотопам кислорода 16O, 17O и 18O существуют три разновидности молекул воды. Таким образом, по изотопному составу существуют 18 различных молекул воды. В действительности любая вода содержит все разновидности молекул.

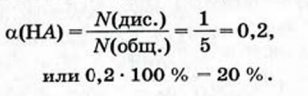

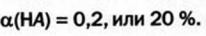

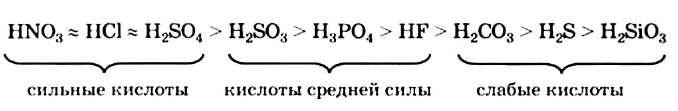

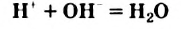

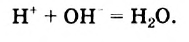

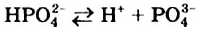

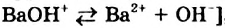

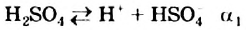

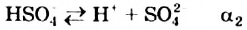

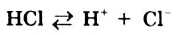

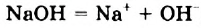

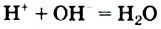

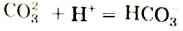

Химические свойства

Вода является наиболее распространённым растворителем на планете Земля, во многом определяющим характер земной химии, как науки. Большая часть химии, при её зарождении как науки, начиналась именно как химия водных растворов веществ.

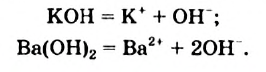

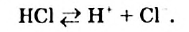

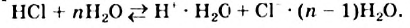

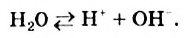

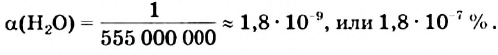

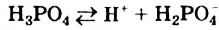

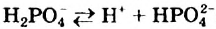

Её иногда рассматривают как амфолит — и кислоту и основание одновременно (катион H+ анион OH−). В отсутствие посторонних веществ в воде одинакова концентрация гидроксид-ионов и ионов водорода (или ионов гидроксония), pKa ≈ 16.

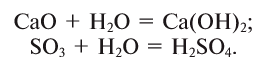

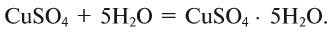

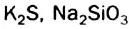

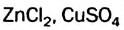

Вода — химически активное вещество. Сильно полярные молекулы воды сольватируют ионы и молекулы, образуют гидраты и кристаллогидраты. Сольволиз, и в частности гидролиз, происходит в живой и неживой природе, и широко используется в химической промышленности.

Воду можно получать:

- в ходе реакций —

- 2H2O2 → 2H2O + O2↑

- NaHCO3 + CH3COOH → CH3COONa + H2O + CO2↑

- 2CH3COOH + CaCO3 → Ca(CH3COO)2 + H2O + CO2↑

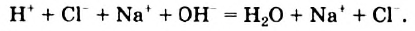

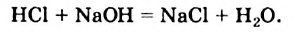

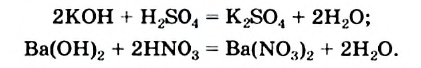

- В ходе реакций нейтрализации —

- H2SO4 + 2KOH → K2SO4 + 2H2O

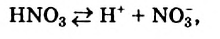

- HNO3 + NH4OH → NH4NO3 + H2O

- Восстановлением водородом оксидов металлов —

- CuO + H2 → Cu + H2O

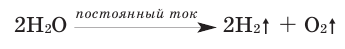

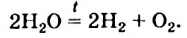

Под воздействием очень высоких температур или электрического тока (при электролизе), а также под воздействием ионизирующего излучения, как установил в 1902 году Фридрих Гизель при исследовании водного раствора бромида радия, вода разлагается на молекулярный кислород и молекулярный водород:

- 2H2O → 2H2↑ + O2↑

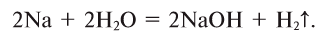

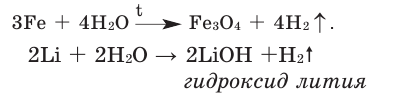

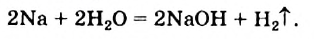

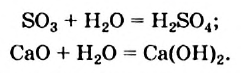

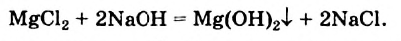

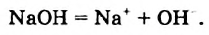

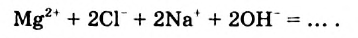

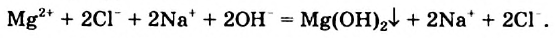

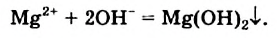

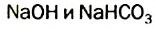

Вода реагирует при комнатной температуре:

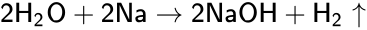

- с активными металлами (натрий, калий, кальций, барий и др.)

- 2H2O + 2Na → 2NaOH + H2↑

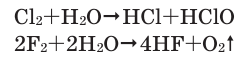

- со фтором и межгалоидными соединениями

- 2H2O + 2F2 → 4HF + O2

- H2O + F2 → HF + HOF (при низких температурах)

- 3H2O + 2IF5 → 5HF + HIO3

- 9H2O + 5BrF3 → 15HF + Br2 + 3HBrO3

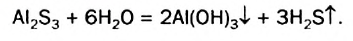

- с солями, образованными слабой кислотой и слабым основанием, вызывая их полный гидролиз

- Al2S3 + 6H2O → 2Al(OH)3↓ + 3H2S↑

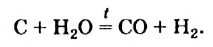

- с ангидридами и галогенангидридами карбоновых и неорганических кислот

- с активными металлорганическими соединениями (диэтилцинк, реактивы Гриньяра, метилнатрий и т. д.)

- с карбидами, нитридами, фосфидами, силицидами, гидридами активных металлов (кальция, натрия, лития и др.)

- со многими солями, образуя гидраты

- с боранами, силанами

- с кетенами, недоокисью углерода

- с фторидами благородных газов

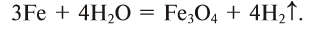

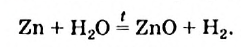

Вода реагирует при нагревании:

- с железом, магнием

- 4H2O + 3Fe → Fe3O4 + 4H2

- с углём, метаном

- H2O + C ⇄ CO + H2

- с некоторыми алкилгалогенидами

Вода реагирует в присутствии катализатора:

- с амидами, эфирами карбоновых кислот

- с ацетиленом и другими алкинами

- с алкенами

- с нитрилами

Волновая функция основного состояния воды

В валентном приближении электронная конфигурация молекулы H2O в основном состоянии: (1a1)1 (1b2)2 (1b1)2 (2b2)0 (3a1)0. Молекула имеет замкнутую оболочку, неспаренных электронов нет. Заняты электронами четыре молекулярные орбитали (МО) — по два электрона на каждой МО ϕi, один со спином α, другой со спином β, или 8 спин-орбиталей ψ. Волновая функция молекулы Ψ.

Виды

Вода на Земле может существовать в трёх основных состояниях:

- жидком

- газообразном

- твёрдом

Вода может приобретать различные формы, которые могут одновременно соседствовать и взаимодействовать друг с другом:

- водяной пар и облака в небе

- морская вода и айсберги

- ледники и реки на поверхности земли

- водоносные слои в земле

Вода способна растворять в себе множество органических и неорганических веществ. Из-за важности воды как источника жизни, её нередко подразделяют на типы по различным принципам.

Виды воды по особенностям происхождения, состава или применения:

- по содержанию катионов кальция и магния

- мягкая вода

- жёсткая вода

- по изотопам водорода в молекуле

- лёгкая вода (по составу почти соответствует обычной)

- тяжёлая вода (дейтериевая)

- сверхтяжёлая вода (тритиевая)

- другие виды

- пресная вода

- дождевая вода

- морская вода

- подземные воды

- минеральная вода

- солоноватая вода

- питьевая вода и водопроводная вода

- дистиллированная вода и деионизированная вода

- сточные воды

- ливневая вода или поверхностные воды

- апирогенная вода

- поливода

- структурированная вода — термин, применяемый в неакадемических теориях

- талая вода

- мёртвая вода и живая вода — виды воды со сказочными свойствами

- святая вода — особый вид воды с мистическими свойствами (согласно религиозным учениям). По христианским представлениям святая вода — это вода, посвященная Богу. Никакие свойства воды как таковой при этом не меняются.

Вода, входящая в состав другого вещества и связанная с ним физическими связями, называется влагой. В зависимости от вида связи, выделяют:

- сорбционную, капиллярную и осмотическую влагу в твёрдых веществах,

- растворённую и эмульсионную влагу в жидкостях,

- водяной пар или туман в газах.

Вещество, содержащее влагу, называют влажным веществом. Влажное вещество, не способное более сорбировать (поглощать) влагу, — насыщенное влагой вещество.

Вещество, в котором содержание влаги пренебрежимо мало при данном конкретном применении, называют сухим веществом. Гипотетическое вещество, совершенно не содержащее влагу, — абсолютно сухое вещество. Сухое вещество, составляющее основу данного влажного вещества, называют сухой частью влажного вещества.

Смесь газа с водяным паром носит название влажный газ (парогазовая смесь — устаревшее название).

В природе

См. также: Роль воды в клетке

В атмосфере нашей планеты вода находится в виде капель малого размера, в облаках и тумане, а также в виде пара. При конденсации выводится из атмосферы в виде атмосферных осадков (дождь, снег, град, роса). В совокупности жидкая водная оболочка Земли называется гидросферой, а твёрдая — криосферой. Вода является важнейшим веществом всех живых организмов на Земле. Предположительно, зарождение жизни на Земле произошло в водной среде.

Мировой океан содержит более 97,54 % земной воды, ледники — 1,81 %, подземные воды — около 0,63 %, реки и озера — 0,009 %, материковые солёные воды — 0,007 %, атмосфера — 0,001 %.

Атмосферные осадки

Основная статья: Атмосферные осадки

Вода за пределами Земли

Основная статья: Внеземная вода

Вода — чрезвычайно распространённое вещество в космосе, однако из-за высокого внутрижидкостного давления вода не может существовать в жидком состоянии в условиях вакуума космоса, отчего она представлена только в виде пара или льда.

Одним из наиболее важных вопросов, связанных с освоением космоса человеком и возможности возникновения жизни на других планетах, является вопрос о наличии воды за пределами Земли в достаточно большой концентрации. Известно, что некоторые кометы более, чем на 50 % состоят из водяного льда. Не стоит, впрочем, забывать, что не любая водная среда пригодна для жизни.

В результате бомбардировки лунного кратера, проведённой 9 октября 2009 года НАСА с использованием космического аппарата LCROSS, впервые были получены достоверные свидетельства наличия на спутнике Земли водяного льда в больших объёмах.

Вода широко распространена в Солнечной системе. Наличие воды (в основном в виде льда) подтверждено на многих спутниках Юпитера и Сатурна: Энцеладе, Тефии, Европе, Ганимеде и др. Вода присутствует в составе всех комет и многих астероидов. Учёными предполагается, что многие транснептуновые объекты имеют в своём составе воду.

Вода в виде паров содержится в атмосфере Солнца (следы), атмосферах Меркурия (3,4 %, также большие количества воды обнаружены в экзосфере Меркурия), Венеры (0,002 %), Луны, Марса (0,03 %), Юпитера (0,0004 %), Европы, Сатурна, Урана (следы) и Нептуна (найден в нижних слоях атмосферы).

Содержание водяного пара в атмосфере Земли у поверхности колеблется от 3—4 % в тропиках до 2·10−5% в Антарктиде.

Кроме того, вода обнаружена на экзопланетах, например HD 189733 A b, HD 209458 b и GJ 1214 b.

Жидкая вода, предположительно, имеется под поверхностью некоторых спутников планет — наиболее вероятно, на Европе — спутнике Юпитера.

Биологическая роль

Основная статья: Роль воды в клетке

Вода играет уникальную роль как вещество, определяющее возможность существования и саму жизнь всех существ на Земле. Она выполняет роль универсального растворителя, в котором происходят основные биохимические процессы живых организмов. Уникальность воды состоит в том, что она достаточно хорошо растворяет как органические, так и неорганические вещества, обеспечивая высокую скорость протекания химических реакций и в то же время — достаточную сложность образующихся комплексных соединений.

Благодаря водородной связи, вода остаётся жидкой в широком диапазоне температур, причём именно в том, который широко представлен на планете Земля в настоящее время.

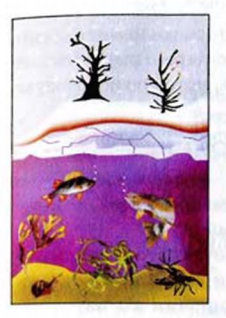

Поскольку у льда плотность меньше, чем у жидкой воды, вода в водоёмах замерзает сверху, а не снизу. Образовавшийся слой льда препятствует дальнейшему промерзанию водоёма, это позволяет его обитателям выжить. Существует и другая точка зрения: если бы вода не расширялась при замерзании, то не разрушались бы клеточные структуры, соответственно замораживание не наносило бы ущерба живым организмам. Некоторые существа (тритоны) переносят замораживание/оттаивание — считается что этому способствует особый состав клеточной плазмы, не расширяющейся при замораживании.

Применение

- В земледелии

Выращивание достаточного количества сельскохозяйственных культур на открытых засушливых землях требует значительных расходов воды на ирригацию, доходящих до 90 % в некоторых странах.

- Для питья и приготовления пищи

Бокал чистой питьевой воды

Живое человеческое тело содержит от 50 % до 75 % воды, в зависимости от веса и возраста. Потеря организмом человека более 10 % воды может привести к смерти. В зависимости от температуры и влажности окружающей среды, физической активности и т. д. человеку нужно выпивать разное количество воды. Ведётся много споров о том, сколько воды нужно потреблять для оптимального функционирования организма.

Питьевая вода представляет собой воду из какого-либо источника, очищенную от микроорганизмов и вредных примесей. Пригодность воды для питья при её обеззараживании перед подачей в водопровод оценивается по количеству кишечных палочек на литр воды, поскольку кишечные палочки распространены и достаточно устойчивы к антибактериальным средствам, и если кишечных палочек будет мало, то будет мало и других микробов. Если кишечных палочек не больше, чем 3 на литр, вода считается пригодной для питья.

- Как растворитель

Вода является растворителем для многих веществ. Она используется для очистки как самого человека, так и различных объектов человеческой деятельности. Вода используется как растворитель в промышленности.

- В качестве теплоносителя

Схема работы атомной электростанции на двухконтурном водо-водяном энергетическом реакторе (ВВЭР)

Среди существующих в природе жидкостей вода обладает наибольшей теплоёмкостью. Теплота её испарения выше теплоты испарения любых других жидкостей, а теплота кристаллизации уступает лишь аммиаку. В качестве теплоносителя воду используют в тепловых сетях, для передачи тепла по теплотрассам от производителей тепла к потребителям. Воду в виде льда используют для охлаждения в системах общественного питания, в медицине. Большинство атомных электростанций используют воду в качестве теплоносителя.

- Как замедлитель

Во многих ядерных реакторах вода используется не только в качестве теплоносителя, но и замедлителя нейтронов для эффективного протекания цепной ядерной реакции. Также существуют тяжеловодные реакторы, в которых в качестве замедлителя используется тяжёлая вода.

- Для пожаротушения

В пожаротушении вода зачастую используется не только как охлаждающая жидкость, но и для изоляции огня от воздуха в составе пены, так как горение поддерживается только при достаточном поступлении кислорода.

- В спорте

Многими видами спорта занимаются на водных поверхностях, на льду, на снегу и даже под водой. Это подводное плавание, хоккей, лодочные виды спорта, биатлон, шорт-трек и др.

- В качестве инструмента

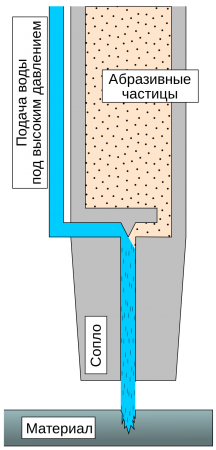

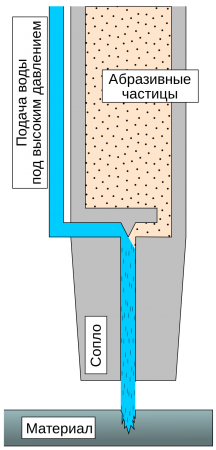

Гидроабразивная резка

Вода используется как инструмент для разрыхления, раскалывания и даже резки пород и материалов. Она используется в добывающей промышленности, горном деле и в производстве. Достаточно распространены установки по резке водой различных материалов: от резины до стали. Вода, выходящая под давлением несколько тысяч атмосфер способна разрезать стальную пластину толщиной несколько миллиметров, или более при добавлении абразивных частиц.

- Для смазки

Вода применяется как смазочный материал для смазки подшипников из древесины, пластиков, текстолита, подшипников с резиновыми обкладками и др. Воду также используют в эмульсионных смазках.

Исследования

Происхождение воды на планете

Основная статья: Происхождение воды на Земле

Происхождение воды на Земле является предметом научных споров. Некоторые учёные считают, что вода была занесена астероидами или кометами на ранней стадии образования Земли, около четырёх миллиардов лет назад, когда планета уже сформировалась в виде шара. В настоящее время установлено, что вода появилась в мантии Земли не позже 2,7 миллиардов лет назад.

Гидрология

Основная статья: Гидрология

Гидроло́гия — наука, изучающая природные воды, их взаимодействие с атмосферой и литосферой, а также явления и процессы, в них протекающие (испарение, замерзание и т. п.).

Предметом изучения гидрологии являются все виды вод гидросферы в океанах, морях, реках, озёрах, водохранилищах, болотах, почвенных и подземных вод.

Гидрология исследует круговорот воды в природе, влияние на него деятельности человека и управление режимом водных объектов и водным режимом отдельных территорий; проводит анализ гидрологических элементов для отдельных территорий и Земли в целом; даёт оценку и прогноз состояния и рационального использования водных ресурсов; пользуется методами, применяемыми в географии, физике и других науках. Данные гидрологии моря используются при плавании и ведении боевых действий надводными кораблями и подводными лодками.

Гидрология подразделяется на океанологию, гидрологию суши и гидрогеологию.

Океанология подразделяется на биологию океана, химию океана, геологию океана, физическую океанологию, и взаимодействие океана и атмосферы.

Гидрология суши подразделяется на гидрологию рек (речную гидрологию, потамологию), озероведение (лимнологию), болотоведение, гляциологию.

Гидрогеология

Основная статья: Гидрогеология

Гидрогеоло́гия (от др.-греч. ὕδωρ «водность» + геология) — наука, изучающая происхождение, условия залегания, состав и закономерности движений подземных вод. Также изучается взаимодействие подземных вод с горными породами, поверхностными водами и атмосферой. В сферу этой науки входят такие вопросы, как динамика подземных вод, гидрогеохимия, поиск и разведка подземных вод, а также мелиоративная и региональная гидрогеология. Гидрогеология тесно связана с гидрологией и геологией, в том числе и с инженерной геологией, метеорологией, геохимией, геофизикой и другими науками о Земле. Она опирается на данные математики, физики, химии и широко использует их методы исследования. Данные гидрогеологии используются, в частности, для решения вопросов водоснабжения, мелиорации и эксплуатации месторождений.

Факты

- В среднем в организме растений и животных содержится более 50 % воды.

- В составе мантии Земли воды содержится в 10—12 раз больше, чем в Мировом океане.

- При средней глубине в 3,6 км Мировой океан покрывает около 71 % поверхности планеты и содержит 97,6 % известных мировых запасов свободной воды.

- Если бы на Земле не было впадин и выпуклостей, вода покрыла бы всю Землю слоем толщиной 3 км.

- При определённых условиях (внутри нанотрубок) молекулы воды образуют новое состояние, при котором они сохраняют способность течь даже при температурах, близких к абсолютному нулю.

- Вода отражает 5 % солнечных лучей, в то время как снег — около 85 %. Под лёд океана проникает только 2 % солнечного света.

- Синий цвет чистой океанской воды в толстом слое объясняется избирательным поглощением и рассеянием света в воде.

- С помощью капель воды из кранов можно создать напряжение до 10 киловольт, опыт называется «Капельница Кельвина».

- Вода — это одно из немногих веществ в природе, которые расширяются при переходе из жидкой фазы в твёрдую (кроме воды, таким свойством обладают сурьма, висмут, галлий, германий и некоторые соединения и смеси).

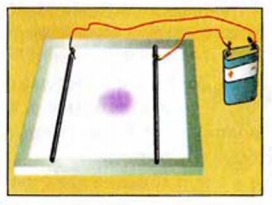

- Вода и водяной пар горят в атмосфере фтора фиолетовым пламенем. Смеси водяного пара со фтором в пределах взрывчатых концентраций взрывоопасны. В результате этой реакции образуются фтороводород и элементарный кислород.

Справочник содержит названия веществ и описания химических формул (в т.ч. структурные формулы и скелетные формулы).

Введите часть названия или формулу для поиска:

Общее число найденных записей: 1.

Показано записей: 1.

Вода

Брутто-формула:

H2O

CAS# 7732-18-5

Названия

Русский:

- Вода [Wiki]

- Оксид водорода(IUPAC)

English:

- Dihydrogen oxide

- Water(CAS) [Wiki]

- oxidane(IUPAC)

Варианты формулы:

Реакции, в которых участвует Вода

-

H2O <=> H^+ + OH^-

-

2H2 + O2 = 2H2O

-

2H2O <=> H3O^+ + OH^-

-

2{M} + 2H2O = 2{M}OH + H2″|^»

, где M =

Li Na K Rb -

2H2O2 -> 2H2O + O2″|^»

|

||

|

||

| Names | ||

|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Water |

||

| Systematic IUPAC name

Oxidane |

||

| Identifiers | ||

|

CAS Number |

|

|

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.902 |

|

|

PubChem CID |

|

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

|

| Properties | ||

|

Chemical formula |

H2O | |

| Molar mass | 18.015 g·mol−1 | |

| Appearance | Nearly colourless liquid or nearly colourless solid (blue if we look through thick layers of water) or colourless gas | |

| Density | Liquid: 0.9998396 g/mL at 0 °C 0.999972 at ~4 °C (Max.) 0.9970474 g/mL at 25 °C Solid: 0.9167 g/mL at 0 °C |

|

| Melting point | 0.00 °C (32.00 °F; 273.15 K) | |

| Boiling point | 99.98 °C (211.96 °F; 373.13 K) | |

| Supplementary data page | ||

| Water (data page) | ||

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). Infobox references |

A globule of liquid water, and the concave depression and rebound in water caused by something dropping through the water surface

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula H2O. It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and nearly colorless chemical substance, and it is the main constituent of Earth’s hydrosphere and the fluids of all known living organisms (in which it acts as a solvent[1]). It is vital for all known forms of life, despite not providing food, energy or organic micronutrients. Its chemical formula, H2O, indicates that each of its molecules contains one oxygen and two hydrogen atoms, connected by covalent bonds. The hydrogen atoms are attached to the oxygen atom at an angle of 104.45°.[2] «Water» is also the name of the liquid state of H2O at standard temperature and pressure.

Because Earth’s environment is relatively close to water’s triple point, water exists on earth as a solid, liquid, and gas.[3] It forms precipitation in the form of rain and aerosols in the form of fog. Clouds consist of suspended droplets of water and ice, its solid state. When finely divided, crystalline ice may precipitate in the form of snow. The gaseous state of water is steam or water vapor.

Water covers about 71% of the Earth’s surface, with seas and oceans making up most of the water volume on earth (about 96.5%).[4] Small portions of water occur as groundwater (1.7%), in the glaciers and the ice caps of Antarctica and Greenland (1.7%), and in the air as vapor, clouds (consisting of ice and liquid water suspended in air), and precipitation (0.001%).[5][6] Water moves continually through the water cycle of evaporation, transpiration (evapotranspiration), condensation, precipitation, and runoff, usually reaching the sea.

Water plays an important role in the world economy. Approximately 70% of the freshwater used by humans goes to agriculture.[7] Fishing in salt and fresh water bodies has been, and continues to be, a major source of food for many parts of the world, providing 6.5% of global protein.[8] Much of the long-distance trade of commodities (such as oil, natural gas, and manufactured products) is transported by boats through seas, rivers, lakes, and canals. Large quantities of water, ice, and steam are used for cooling and heating, in industry and homes. Water is an excellent solvent for a wide variety of substances both mineral and organic; as such it is widely used in industrial processes, and in cooking and washing. Water, ice and snow are also central to many sports and other forms of entertainment, such as swimming, pleasure boating, boat racing, surfing, sport fishing, diving, ice skating and skiing.

Etymology

The word water comes from Old English wæter, from Proto-Germanic *watar (source also of Old Saxon watar, Old Frisian wetir, Dutch water, Old High German wazzar, German Wasser, vatn, Gothic 𐍅𐌰𐍄𐍉 (wato), from Proto-Indo-European *wod-or, suffixed form of root *wed- (‘water‘; ‘wet‘).[9] Also cognate, through the Indo-European root, with Greek ύδωρ (ýdor; from Ancient Greek ὕδωρ (hýdōr), whence English ‘hydro-‘), Russian вода́ (vodá), Irish uisce, and Albanian ujë.

History

Properties

A water molecule consists of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom

Water (H2O) is a polar inorganic compound. At room temperature it is a tasteless and odorless liquid, nearly colorless with a hint of blue. This simplest hydrogen chalcogenide is by far the most studied chemical compound and is described as the «universal solvent» for its ability to dissolve many substances.[10][11] This allows it to be the «solvent of life»:[12] indeed, water as found in nature almost always includes various dissolved substances, and special steps are required to obtain chemically pure water. Water is the only common substance to exist as a solid, liquid, and gas in normal terrestrial conditions.[13]

States

The three common states of matter

Along with oxidane, water is one of the two official names for the chemical compound H

2O;[14] it is also the liquid phase of H

2O.[15] The other two common states of matter of water are the solid phase, ice, and the gaseous phase, water vapor or steam. The addition or removal of heat can cause phase transitions: freezing (water to ice), melting (ice to water), vaporization (water to vapor), condensation (vapor to water), sublimation (ice to vapor) and deposition (vapor to ice).[16]

Density

Water differs from most liquids in that it becomes less dense as it freezes.[a] In 1 atm pressure, it reaches its maximum density of 999.972 kg/m3 (62.4262 lb/cu ft) at 3.98 °C (39.16 °F), or almost 1,000 kg/m3 (62.43 lb/cu ft) at almost 4 °C (39 °F).[18][19] The density of ice is 917 kg/m3 (57.25 lb/cu ft), an expansion of 9%.[20][21] This expansion can exert enormous pressure, bursting pipes and cracking rocks.[22]

In a lake or ocean, water at 4 °C (39 °F) sinks to the bottom, and ice forms on the surface, floating on the liquid water. This ice insulates the water below, preventing it from freezing solid. Without this protection, most aquatic organisms residing in lakes would perish during the winter.[23]

Magnetism

Water is a diamagnetic material.[24] Though interaction is weak, with superconducting magnets it can attain a notable interaction.[24]

Phase transitions

At a pressure of one atmosphere (atm), ice melts or water freezes (solidifies) at 0 °C (32 °F)) and water boils or vapor condenses at 100 °C (212 °F). However, even below the boiling point, water can change to vapor at its surface by evaporation (vaporization throughout the liquid is known as boiling). Sublimation and deposition also occur on surfaces.[16] For example, frost is deposited on cold surfaces while snowflakes form by deposition on an aerosol particle or ice nucleus.[25] In the process of freeze-drying, a food is frozen and then stored at low pressure so the ice on its surface sublimates.[26]

The melting and boiling points depend on pressure. A good approximation for the rate of change of the melting temperature with pressure is given by the Clausius–Clapeyron relation:

where

The Clausius-Clapeyron relation also applies to the boiling point, but with the liquid/gas transition the vapor phase has a much lower density than the liquid phase, so the boiling point increases with pressure.[29] Water can remain in a liquid state at high temperatures in the deep ocean or underground. For example, temperatures exceed 205 °C (401 °F) in Old Faithful, a geyser in Yellowstone National Park.[30] In hydrothermal vents, the temperature can exceed 400 °C (752 °F).[31]

At sea level, the boiling point of water is 100 °C (212 °F). As atmospheric pressure decreases with altitude, the boiling point decreases by 1 °C every 274 meters. High-altitude cooking takes longer than sea-level cooking. For example, at 1,524 metres (5,000 ft), cooking time must be increased by a fourth to achieve the desired result.[32] (Conversely, a pressure cooker can be used to decrease cooking times by raising the boiling temperature.[33])

In a vacuum, water will boil at room temperature.[34]

Triple and critical points

Phase diagram of water (simplified)

On a pressure/temperature phase diagram (see figure), there are curves separating solid from vapor, vapor from liquid, and liquid from solid. These meet at a single point called the triple point, where all three phases can coexist. The triple point is at a temperature of 273.16 K (0.01 °C; 32.02 °F) and a pressure of 611.657 pascals (0.00604 atm; 0.0887 psi);[35] it is the lowest pressure at which liquid water can exist. Until 2019, the triple point was used to define the Kelvin temperature scale.[36][37]

The water/vapor phase curve terminates at 647.096 K (373.946 °C; 705.103 °F) and 22.064 megapascals (3,200.1 psi; 217.75 atm).[38] This is known as the critical point. At higher temperatures and pressures the liquid and vapor phases form a continuous phase called a supercritical fluid. It can be gradually compressed or expanded between gas-like and liquid-like densities; its properties (which are quite different from those of ambient water) are sensitive to density. For example, for suitable pressures and temperatures it can mix freely with nonpolar compounds, including most organic compounds. This makes it useful in a variety of applications including high-temperature electrochemistry and as an ecologically benign solvent or catalyst in chemical reactions involving organic compounds. In Earth’s mantle, it acts as a solvent during mineral formation, dissolution and deposition.[39][40]

Phases of ice and water

Main article: Ice

The normal form of ice on the surface of Earth is Ice Ih, a phase that forms crystals with hexagonal symmetry. Another with cubic crystalline symmetry, Ice Ic, can occur in the upper atmosphere.[41] As the pressure increases, ice forms other crystal structures. As of 2019, 17 have been experimentally confirmed and several more are predicted theoretically (see Ice).[42] The 18th form of ice, ice XVIII, a face-centred-cubic, superionic ice phase, was discovered when a droplet of water was subject to a shock wave that raised the water’s pressure to millions of atmospheres and its temperature to thousands of degrees, resulting in a structure of rigid oxygen atoms in which hydrogen atoms flowed freely.[43][44] When sandwiched between layers of graphene, ice forms a square lattice.[45]

The details of the chemical nature of liquid water are not well understood; some theories suggest that its unusual behaviour is due to the existence of 2 liquid states.[19][46][47][48]

Taste and odor

Pure water is usually described as tasteless and odorless, although humans have specific sensors that can feel the presence of water in their mouths,[49][50] and frogs are known to be able to smell it.[51] However, water from ordinary sources (including bottled mineral water) usually has many dissolved substances, that may give it varying tastes and odors. Humans and other animals have developed senses that enable them to evaluate the potability of water in order to avoid water that is too salty or putrid.[52]

Color and appearance

Pure water is visibly blue due to absorption of light in the region c. 600–800 nm.[53] The color can be easily observed in a glass of tap-water placed against a pure white background, in daylight. The principal absorption bands responsible for the color are overtones of the O–H stretching vibrations. The apparent intensity of the color increases with the depth of the water column, following Beer’s law. This also applies, for example, with a swimming pool when the light source is sunlight reflected from the pool’s white tiles.

In nature, the color may also be modified from blue to green due to the presence of suspended solids or algae.

In industry, near-infrared spectroscopy is used with aqueous solutions as the greater intensity of the lower overtones of water means that glass cuvettes with short path-length may be employed. To observe the fundamental stretching absorption spectrum of water or of an aqueous solution in the region around 3,500 cm−1 (2.85 μm)[54] a path length of about 25 μm is needed. Also, the cuvette must be both transparent around 3500 cm−1 and insoluble in water; calcium fluoride is one material that is in common use for the cuvette windows with aqueous solutions.

The Raman-active fundamental vibrations may be observed with, for example, a 1 cm sample cell.

Aquatic plants, algae, and other photosynthetic organisms can live in water up to hundreds of meters deep, because sunlight can reach them.

Practically no sunlight reaches the parts of the oceans below 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) of depth.

The refractive index of liquid water (1.333 at 20 °C (68 °F)) is much higher than that of air (1.0), similar to those of alkanes and ethanol, but lower than those of glycerol (1.473), benzene (1.501), carbon disulfide (1.627), and common types of glass (1.4 to 1.6). The refraction index of ice (1.31) is lower than that of liquid water.

Polar molecule

Tetrahedral structure of water

In a water molecule, the hydrogen atoms form a 104.5° angle with the oxygen atom. The hydrogen atoms are close to two corners of a tetrahedron centered on the oxygen. At the other two corners are lone pairs of valence electrons that do not participate in the bonding. In a perfect tetrahedron, the atoms would form a 109.5° angle, but the repulsion between the lone pairs is greater than the repulsion between the hydrogen atoms.[55][56] The O–H bond length is about 0.096 nm.[57]

Other substances have a tetrahedral molecular structure, for example, methane (CH

4) and hydrogen sulfide (H

2S). However, oxygen is more electronegative (holds on to its electrons more tightly) than most other elements, so the oxygen atom retains a negative charge while the hydrogen atoms are positively charged. Along with the bent structure, this gives the molecule an electrical dipole moment and it is classified as a polar molecule.[58]

Water is a good polar solvent, that dissolves many salts and hydrophilic organic molecules such as sugars and simple alcohols such as ethanol. Water also dissolves many gases, such as oxygen and carbon dioxide—the latter giving the fizz of carbonated beverages, sparkling wines and beers. In addition, many substances in living organisms, such as proteins, DNA and polysaccharides, are dissolved in water. The interactions between water and the subunits of these biomacromolecules shape protein folding, DNA base pairing, and other phenomena crucial to life (hydrophobic effect).

Many organic substances (such as fats and oils and alkanes) are hydrophobic, that is, insoluble in water. Many inorganic substances are insoluble too, including most metal oxides, sulfides, and silicates.

Hydrogen bonding

Because of its polarity, a molecule of water in the liquid or solid state can form up to four hydrogen bonds with neighboring molecules. Hydrogen bonds are about ten times as strong as the Van der Waals force that attracts molecules to each other in most liquids. This is the reason why the melting and boiling points of water are much higher than those of other analogous compounds like hydrogen sulfide. They also explain its exceptionally high specific heat capacity (about 4.2 J/g/K), heat of fusion (about 333 J/g), heat of vaporization (2257 J/g), and thermal conductivity (between 0.561 and 0.679 W/m/K). These properties make water more effective at moderating Earth’s climate, by storing heat and transporting it between the oceans and the atmosphere. The hydrogen bonds of water are around 23 kJ/mol (compared to a covalent O-H bond at 492 kJ/mol). Of this, it is estimated that 90% is attributable to electrostatics, while the remaining 10% is partially covalent.[59]

These bonds are the cause of water’s high surface tension[60] and capillary forces. The capillary action refers to the tendency of water to move up a narrow tube against the force of gravity. This property is relied upon by all vascular plants, such as trees.[citation needed]

Specific heat capacity of water[61]

Self-ionization

Water is a weak solution of hydronium hydroxide – there is an equilibrium 2H

2O ⇔ H

3O+

+ OH−

, in combination with solvation of the resulting hydronium ions.

Electrical conductivity and electrolysis

Pure water has a low electrical conductivity, which increases with the dissolution of a small amount of ionic material such as common salt.

Liquid water can be split into the elements hydrogen and oxygen by passing an electric current through it—a process called electrolysis. The decomposition requires more energy input than the heat released by the inverse process (285.8 kJ/mol, or 15.9 MJ/kg).[62]

Mechanical properties

Liquid water can be assumed to be incompressible for most purposes: its compressibility ranges from 4.4 to 5.1×10−10 Pa−1 in ordinary conditions.[63] Even in oceans at 4 km depth, where the pressure is 400 atm, water suffers only a 1.8% decrease in volume.[64]

The viscosity of water is about 10−3 Pa·s or 0.01 poise at 20 °C (68 °F), and the speed of sound in liquid water ranges between 1,400 and 1,540 meters per second (4,600 and 5,100 ft/s) depending on temperature. Sound travels long distances in water with little attenuation, especially at low frequencies (roughly 0.03 dB/km for 1 kHz), a property that is exploited by cetaceans and humans for communication and environment sensing (sonar).[65]

Reactivity

Metallic elements which are more electropositive than hydrogen, particularly the alkali metals and alkaline earth metals such as lithium, sodium, calcium, potassium and cesium displace hydrogen from water, forming hydroxides and releasing hydrogen. At high temperatures, carbon reacts with steam to form carbon monoxide and hydrogen.

On Earth

Hydrology is the study of the movement, distribution, and quality of water throughout the Earth. The study of the distribution of water is hydrography. The study of the distribution and movement of groundwater is hydrogeology, of glaciers is glaciology, of inland waters is limnology and distribution of oceans is oceanography. Ecological processes with hydrology are in the focus of ecohydrology.

The collective mass of water found on, under, and over the surface of a planet is called the hydrosphere. Earth’s approximate water volume (the total water supply of the world) is 1.386 billion cubic kilometres (333 million cubic miles).[5]

Liquid water is found in bodies of water, such as an ocean, sea, lake, river, stream, canal, pond, or puddle. The majority of water on Earth is seawater. Water is also present in the atmosphere in solid, liquid, and vapor states. It also exists as groundwater in aquifers.

Water is important in many geological processes. Groundwater is present in most rocks, and the pressure of this groundwater affects patterns of faulting. Water in the mantle is responsible for the melt that produces volcanoes at subduction zones. On the surface of the Earth, water is important in both chemical and physical weathering processes. Water, and to a lesser but still significant extent, ice, are also responsible for a large amount of sediment transport that occurs on the surface of the earth. Deposition of transported sediment forms many types of sedimentary rocks, which make up the geologic record of Earth history.

Water cycle

The water cycle (known scientifically as the hydrologic cycle) is the continuous exchange of water within the hydrosphere, between the atmosphere, soil water, surface water, groundwater, and plants.

Water moves perpetually through each of these regions in the water cycle consisting of the following transfer processes:

- evaporation from oceans and other water bodies into the air and transpiration from land plants and animals into the air.

- precipitation, from water vapor condensing from the air and falling to the earth or ocean.

- runoff from the land usually reaching the sea.

Most water vapors found mostly in the ocean returns to it, but winds carry water vapor over land at the same rate as runoff into the sea, about 47 Tt per year whilst evaporation and transpiration happening in land masses also contribute another 72 Tt per year. Precipitation, at a rate of 119 Tt per year over land, has several forms: most commonly rain, snow, and hail, with some contribution from fog and dew.[66] Dew is small drops of water that are condensed when a high density of water vapor meets a cool surface. Dew usually forms in the morning when the temperature is the lowest, just before sunrise and when the temperature of the earth’s surface starts to increase.[67] Condensed water in the air may also refract sunlight to produce rainbows.

Water runoff often collects over watersheds flowing into rivers. Through erosion, runoff shapes the environment creating river valleys and deltas which provide rich soil and level ground for the establishment of population centers. A flood occurs when an area of land, usually low-lying, is covered with water which occurs when a river overflows its banks or a storm surge happens. On the other hand, drought is an extended period of months or years when a region notes a deficiency in its water supply. This occurs when a region receives consistently below average precipitation either due to its topography or due to its location in terms of latitude.

Water resources

Water resources are natural resources of water that are potentially useful for humans,[68] for example as a source of drinking water supply or irrigation water. Water occurs as both «stocks» and «flows». Water can be stored as lakes, water vapor, groundwater or aquifers, and ice and snow. Of the total volume of global freshwater, an estimated 69 percent is stored in glaciers and permanent snow cover; 30 percent is in groundwater; and the remaining 1 percent in lakes, rivers, the atmosphere, and biota.[69] The length of time water remains in storage is highly variable: some aquifers consist of water stored over thousands of years but lake volumes may fluctuate on a seasonal basis, decreasing during dry periods and increasing during wet ones. A substantial fraction of the water supply for some regions consists of water extracted from water stored in stocks, and when withdrawals exceed recharge, stocks decrease. By some estimates, as much as 30 percent of total water used for irrigation comes from unsustainable withdrawals of groundwater, causing groundwater depletion.[70]

Seawater and tides

Seawater contains about 3.5% sodium chloride on average, plus smaller amounts of other substances. The physical properties of seawater differ from fresh water in some important respects. It freezes at a lower temperature (about −1.9 °C (28.6 °F)) and its density increases with decreasing temperature to the freezing point, instead of reaching maximum density at a temperature above freezing. The salinity of water in major seas varies from about 0.7% in the Baltic Sea to 4.0% in the Red Sea. (The Dead Sea, known for its ultra-high salinity levels of between 30 and 40%, is really a salt lake.)

Tides are the cyclic rising and falling of local sea levels caused by the tidal forces of the Moon and the Sun acting on the oceans. Tides cause changes in the depth of the marine and estuarine water bodies and produce oscillating currents known as tidal streams. The changing tide produced at a given location is the result of the changing positions of the Moon and Sun relative to the Earth coupled with the effects of Earth rotation and the local bathymetry. The strip of seashore that is submerged at high tide and exposed at low tide, the intertidal zone, is an important ecological product of ocean tides.

-

High tide

-

Low tide

Effects on life

From a biological standpoint, water has many distinct properties that are critical for the proliferation of life. It carries out this role by allowing organic compounds to react in ways that ultimately allow replication. All known forms of life depend on water. Water is vital both as a solvent in which many of the body’s solutes dissolve and as an essential part of many metabolic processes within the body. Metabolism is the sum total of anabolism and catabolism. In anabolism, water is removed from molecules (through energy requiring enzymatic chemical reactions) in order to grow larger molecules (e.g., starches, triglycerides, and proteins for storage of fuels and information). In catabolism, water is used to break bonds in order to generate smaller molecules (e.g., glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids to be used for fuels for energy use or other purposes). Without water, these particular metabolic processes could not exist.

Water is fundamental to photosynthesis and respiration. Photosynthetic cells use the sun’s energy to split off water’s hydrogen from oxygen.[71] Hydrogen is combined with CO

2 (absorbed from air or water) to form glucose and release oxygen.[citation needed] All living cells use such fuels and oxidize the hydrogen and carbon to capture the sun’s energy and reform water and CO

2 in the process (cellular respiration).

Water is also central to acid-base neutrality and enzyme function. An acid, a hydrogen ion (H+

, that is, a proton) donor, can be neutralized by a base, a proton acceptor such as a hydroxide ion (OH−

) to form water. Water is considered to be neutral, with a pH (the negative log of the hydrogen ion concentration) of 7. Acids have pH values less than 7 while bases have values greater than 7.

Aquatic life forms

Earth surface waters are filled with life. The earliest life forms appeared in water; nearly all fish live exclusively in water, and there are many types of marine mammals, such as dolphins and whales. Some kinds of animals, such as amphibians, spend portions of their lives in water and portions on land. Plants such as kelp and algae grow in the water and are the basis for some underwater ecosystems. Plankton is generally the foundation of the ocean food chain.

Aquatic vertebrates must obtain oxygen to survive, and they do so in various ways. Fish have gills instead of lungs, although some species of fish, such as the lungfish, have both. Marine mammals, such as dolphins, whales, otters, and seals need to surface periodically to breathe air. Some amphibians are able to absorb oxygen through their skin. Invertebrates exhibit a wide range of modifications to survive in poorly oxygenated waters including breathing tubes (see insect and mollusc siphons) and gills (Carcinus). However, as invertebrate life evolved in an aquatic habitat most have little or no specialization for respiration in water.

Effects on human civilization

Civilization has historically flourished around rivers and major waterways; Mesopotamia, one of the so-called cradles of civilization, was situated between the major rivers Tigris and Euphrates; the ancient society of the Egyptians depended entirely upon the Nile. The early Indus Valley civilization (c. 3300 BCE to 1300 BCE) developed along the Indus River and tributaries that flowed out of the Himalayas. Rome was also founded on the banks of the Italian river Tiber. Large metropolises like Rotterdam, London, Montreal, Paris, New York City, Buenos Aires, Shanghai, Tokyo, Chicago, and Hong Kong owe their success in part to their easy accessibility via water and the resultant expansion of trade. Islands with safe water ports, like Singapore, have flourished for the same reason. In places such as North Africa and the Middle East, where water is more scarce, access to clean drinking water was and is a major factor in human development.

Health and pollution

Water fit for human consumption is called drinking water or potable water. Water that is not potable may be made potable by filtration or distillation, or by a range of other methods. More than 660 million people do not have access to safe drinking water.[72][73]

Water that is not fit for drinking but is not harmful to humans when used for swimming or bathing is called by various names other than potable or drinking water, and is sometimes called safe water, or «safe for bathing». Chlorine is a skin and mucous membrane irritant that is used to make water safe for bathing or drinking. Its use is highly technical and is usually monitored by government regulations (typically 1 part per million (ppm) for drinking water, and 1–2 ppm of chlorine not yet reacted with impurities for bathing water). Water for bathing may be maintained in satisfactory microbiological condition using chemical disinfectants such as chlorine or ozone or by the use of ultraviolet light.

Water reclamation is the process of converting wastewater (most commonly sewage, also called municipal wastewater) into water that can be reused for other purposes. There are 2.3 billion people who reside in nations with water scarcities, which means that each individual receives less than 1,700 cubic metres (60,000 cu ft) of water annually. 380 billion cubic metres (13×1012 cu ft) of municipal wastewater are produced globally each year.[74][75][76]

Freshwater is a renewable resource, recirculated by the natural hydrologic cycle, but pressures over access to it result from the naturally uneven distribution in space and time, growing economic demands by agriculture and industry, and rising populations. Currently, nearly a billion people around the world lack access to safe, affordable water. In 2000, the United Nations established the Millennium Development Goals for water to halve by 2015 the proportion of people worldwide without access to safe water and sanitation. Progress toward that goal was uneven, and in 2015 the UN committed to the Sustainable Development Goals of achieving universal access to safe and affordable water and sanitation by 2030. Poor water quality and bad sanitation are deadly; some five million deaths a year are caused by water-related diseases. The World Health Organization estimates that safe water could prevent 1.4 million child deaths from diarrhoea each year.[77]

In developing countries, 90% of all municipal wastewater still goes untreated into local rivers and streams.[78] Some 50 countries, with roughly a third of the world’s population, also suffer from medium or high water scarcity and 17 of these extract more water annually than is recharged through their natural water cycles.[79] The strain not only affects surface freshwater bodies like rivers and lakes, but it also degrades groundwater resources.

Human uses

Total water withdrawals for agricultural, industrial and municipal purposes per capita, measured in cubic metres (m3) per year in 2010[80]

Agriculture

The most substantial human use of water is for agriculture, including irrigated agriculture, which accounts for as much as 80 to 90 percent of total human water consumption.[81] In the United States, 42% of freshwater withdrawn for use is for irrigation, but the vast majority of water «consumed» (used and not returned to the environment) goes to agriculture.[82]

Access to fresh water is often taken for granted, especially in developed countries that have built sophisticated water systems for collecting, purifying, and delivering water, and removing wastewater. But growing economic, demographic, and climatic pressures are increasing concerns about water issues, leading to increasing competition for fixed water resources, giving rise to the concept of peak water.[83] As populations and economies continue to grow, consumption of water-thirsty meat expands, and new demands rise for biofuels or new water-intensive industries, new water challenges are likely.[84]

An assessment of water management in agriculture was conducted in 2007 by the International Water Management Institute in Sri Lanka to see if the world had sufficient water to provide food for its growing population.[85] It assessed the current availability of water for agriculture on a global scale and mapped out locations suffering from water scarcity. It found that a fifth of the world’s people, more than 1.2 billion, live in areas of physical water scarcity, where there is not enough water to meet all demands. A further 1.6 billion people live in areas experiencing economic water scarcity, where the lack of investment in water or insufficient human capacity make it impossible for authorities to satisfy the demand for water. The report found that it would be possible to produce the food required in the future, but that continuation of today’s food production and environmental trends would lead to crises in many parts of the world. To avoid a global water crisis, farmers will have to strive to increase productivity to meet growing demands for food, while industries and cities find ways to use water more efficiently.[86]

Water scarcity is also caused by production of water intensive products. For example, cotton: 1 kg of cotton—equivalent of a pair of jeans—requires 10.9 cubic meters (380 cu ft) water to produce. While cotton accounts for 2.4% of world water use, the water is consumed in regions that are already at a risk of water shortage. Significant environmental damage has been caused: for example, the diversion of water by the former Soviet Union from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers to produce cotton was largely responsible for the disappearance of the Aral Sea.[87]

-

Water requirement per tonne of food product

As a scientific standard

On 7 April 1795, the gram was defined in France to be equal to «the absolute weight of a volume of pure water equal to a cube of one-hundredth of a meter, and at the temperature of melting ice».[88] For practical purposes though, a metallic reference standard was required, one thousand times more massive, the kilogram. Work was therefore commissioned to determine precisely the mass of one liter of water. In spite of the fact that the decreed definition of the gram specified water at 0 °C (32 °F)—a highly reproducible temperature—the scientists chose to redefine the standard and to perform their measurements at the temperature of highest water density, which was measured at the time as 4 °C (39 °F).[89]

The Kelvin temperature scale of the SI system was based on the triple point of water, defined as exactly 273.16 K (0.01 °C; 32.02 °F), but as of May 2019 is based on the Boltzmann constant instead. The scale is an absolute temperature scale with the same increment as the Celsius temperature scale, which was originally defined according to the boiling point (set to 100 °C (212 °F)) and melting point (set to 0 °C (32 °F)) of water.

Natural water consists mainly of the isotopes hydrogen-1 and oxygen-16, but there is also a small quantity of heavier isotopes oxygen-18, oxygen-17, and hydrogen-2 (deuterium). The percentage of the heavier isotopes is very small, but it still affects the properties of water. Water from rivers and lakes tends to contain less heavy isotopes than seawater. Therefore, standard water is defined in the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water specification.

For drinking

Water availability: the fraction of the population using improved water sources by country

Roadside fresh water outlet from glacier, Nubra

The human body contains from 55% to 78% water, depending on body size.[90][user-generated source?] To function properly, the body requires between one and seven liters (0.22 and 1.54 imp gal; 0.26 and 1.85 U.S. gal)[citation needed] of water per day to avoid dehydration; the precise amount depends on the level of activity, temperature, humidity, and other factors. Most of this is ingested through foods or beverages other than drinking straight water. It is not clear how much water intake is needed by healthy people, though the British Dietetic Association advises that 2.5 liters of total water daily is the minimum to maintain proper hydration, including 1.8 liters (6 to 7 glasses) obtained directly from beverages.[91] Medical literature favors a lower consumption, typically 1 liter of water for an average male, excluding extra requirements due to fluid loss from exercise or warm weather.[92]

Healthy kidneys can excrete 0.8 to 1 liter of water per hour, but stress such as exercise can reduce this amount. People can drink far more water than necessary while exercising, putting them at risk of water intoxication (hyperhydration), which can be fatal.[93][94] The popular claim that «a person should consume eight glasses of water per day» seems to have no real basis in science.[95] Studies have shown that extra water intake, especially up to 500 milliliters (18 imp fl oz; 17 U.S. fl oz) at mealtime, was associated with weight loss.[96][97][98][99][100][101] Adequate fluid intake is helpful in preventing constipation.[102]

An original recommendation for water intake in 1945 by the Food and Nutrition Board of the U.S. National Research Council read: «An ordinary standard for diverse persons is 1 milliliter for each calorie of food. Most of this quantity is contained in prepared foods.»[103] The latest dietary reference intake report by the U.S. National Research Council in general recommended, based on the median total water intake from US survey data (including food sources): 3.7 liters (0.81 imp gal; 0.98 U.S. gal) for men and 2.7 liters (0.59 imp gal; 0.71 U.S. gal) of water total for women, noting that water contained in food provided approximately 19% of total water intake in the survey.[104]

Specifically, pregnant and breastfeeding women need additional fluids to stay hydrated. The US Institute of Medicine recommends that, on average, men consume 3 liters (0.66 imp gal; 0.79 U.S. gal) and women 2.2 liters (0.48 imp gal; 0.58 U.S. gal); pregnant women should increase intake to 2.4 liters (0.53 imp gal; 0.63 U.S. gal) and breastfeeding women should get 3 liters (12 cups), since an especially large amount of fluid is lost during nursing.[105] Also noted is that normally, about 20% of water intake comes from food, while the rest comes from drinking water and beverages (caffeinated included). Water is excreted from the body in multiple forms; through urine and feces, through sweating, and by exhalation of water vapor in the breath. With physical exertion and heat exposure, water loss will increase and daily fluid needs may increase as well.

Humans require water with few impurities. Common impurities include metal salts and oxides, including copper, iron, calcium and lead,[106][full citation needed] and/or harmful bacteria, such as Vibrio. Some solutes are acceptable and even desirable for taste enhancement and to provide needed electrolytes.[107]

The single largest (by volume) freshwater resource suitable for drinking is Lake Baikal in Siberia.[108]

Washing

This section is an excerpt from Washing.[edit]

A woman washes her hands with soap and water.

Washing is a method of cleaning, usually with water and soap or detergent. Washing and then rinsing both body and clothing is an essential part of good hygiene and health. [citation needed]

Often people use soaps and detergents to assist in the emulsification of oils and dirt particles so they can be washed away. The soap can be applied directly, or with the aid of a washcloth.

People wash themselves, or bathe periodically for religious ritual or therapeutic purposes[109] or as a recreational activity.

In Europe, some people use a bidet to wash their external genitalia and the anal region after using the toilet, instead of using toilet paper.[110] The bidet is common in predominantly Catholic countries where water is considered essential for anal cleansing.[111]

More frequent is washing of just the hands, e.g. before and after preparing food and eating, after using the toilet, after handling something dirty, etc. Hand washing is important in reducing the spread of germs.[112][113][114] Also common is washing the face, which is done after waking up, or to keep oneself cool during the day. Brushing one’s teeth is also essential for hygiene and is a part of washing.

‘Washing’ can also refer to the washing of clothing or other cloth items, like bedsheets, whether by hand or with a washing machine. It can also refer to washing one’s car, by lathering the exterior with car soap, then rinsing it off with a hose, or washing cookware.

Excessive washing may damage the hair, causing dandruff, or cause rough skin/skin lesions.[115][116]

Transportation

Maritime transport (or ocean transport) or more generally waterborne transport, is the transport of people (passengers) or goods (cargo) via waterways. Freight transport by sea has been widely used throughout recorded history. The advent of aviation has diminished the importance of sea travel for passengers, though it is still popular for short trips and pleasure cruises. Transport by water is cheaper than transport by air or ground,[117] but significantly slower for longer distances. Maritime transport accounts for roughly 80% of international trade, according to UNCTAD in 2020.

Maritime transport can be realized over any distance by boat, ship, sailboat or barge, over oceans and lakes, through canals or along rivers. Shipping may be for commerce, recreation, or military purposes. While extensive inland shipping is less critical today, the major waterways of the world including many canals are still very important and are integral parts of worldwide economies. Particularly, especially any material can be moved by water; however, water transport becomes impractical when material delivery is time-critical such as various types of perishable produce. Still, water transport is highly cost effective with regular schedulable cargoes, such as trans-oceanic shipping of consumer products – and especially for heavy loads or bulk cargos, such as coal, coke, ores, or grains. Arguably, the industrial revolution had its first impacts where cheap water transport by canal, navigations, or shipping by all types of watercraft on natural waterways supported cost-effective bulk transport.

Containerization revolutionized maritime transport starting in the 1970s. «General cargo» includes goods packaged in boxes, cases, pallets, and barrels. When a cargo is carried in more than one mode, it is intermodal or co-modal.

Chemical uses

Water is widely used in chemical reactions as a solvent or reactant and less commonly as a solute or catalyst. In inorganic reactions, water is a common solvent, dissolving many ionic compounds, as well as other polar compounds such as ammonia and compounds closely related to water. In organic reactions, it is not usually used as a reaction solvent, because it does not dissolve the reactants well and is amphoteric (acidic and basic) and nucleophilic. Nevertheless, these properties are sometimes desirable. Also, acceleration of Diels-Alder reactions by water has been observed. Supercritical water has recently been a topic of research. Oxygen-saturated supercritical water combusts organic pollutants efficiently.

Heat exchange

Water and steam are a common fluid used for heat exchange, due to its availability and high heat capacity, both for cooling and heating. Cool water may even be naturally available from a lake or the sea. It is especially effective to transport heat through vaporization and condensation of water because of its large latent heat of vaporization. A disadvantage is that metals commonly found in industries such as steel and copper are oxidized faster by untreated water and steam. In almost all thermal power stations, water is used as the working fluid (used in a closed-loop between boiler, steam turbine, and condenser), and the coolant (used to exchange the waste heat to a water body or carry it away by evaporation in a cooling tower). In the United States, cooling power plants is the largest use of water.[118]

In the nuclear power industry, water can also be used as a neutron moderator. In most nuclear reactors, water is both a coolant and a moderator. This provides something of a passive safety measure, as removing the water from the reactor also slows the nuclear reaction down. However other methods are favored for stopping a reaction and it is preferred to keep the nuclear core covered with water so as to ensure adequate cooling.

Fire considerations

Water has a high heat of vaporization and is relatively inert, which makes it a good fire extinguishing fluid. The evaporation of water carries heat away from the fire. It is dangerous to use water on fires involving oils and organic solvents because many organic materials float on water and the water tends to spread the burning liquid.

Use of water in fire fighting should also take into account the hazards of a steam explosion, which may occur when water is used on very hot fires in confined spaces, and of a hydrogen explosion, when substances which react with water, such as certain metals or hot carbon such as coal, charcoal, or coke graphite, decompose the water, producing water gas.